Abstract

Objectives

In 2006, the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges reported that the shortage (≥1,500) of public health veterinarians is expected to increase tenfold by 2020. In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Preventive Medicine Fellows conducted a pilot project among CDC veterinarians to identify national veterinary public health workforce concerns and potential policy strategies.

Methods

Fellows surveyed a convenience sample (19/91) of public health veterinarians at CDC to identify veterinary workforce recruitment and retention problems faced by federal agencies; responses were categorized into themes. A focus group (20/91) of staff veterinarians subsequently prioritized the categorized themes from least to most important. Participants identified activities to address the three recruitment concerns with the highest combined weight.

Results

Participants identified the following three highest prioritized problems faced by federal agencies when recruiting veterinarians to public health: (1) lack of awareness of veterinarians' contributions to public health practice, (2) competitive salaries, and (3) employment and training opportunities. Similarly, key concerns identified regarding retention of public health practice veterinarians included: (1) lack of recognition of veterinary qualifications, (2) competitive salaries, and (3) seamless integration of veterinary and human public health.

Conclusions

Findings identified multiple barriers that can affect recruitment and retention of veterinarians engaged in public health practice. Next steps should include replicating project efforts among a national sample of public health veterinarians. A committed and determined long-term effort might be required to sustain initiatives and policy proposals to increase U.S. veterinary public health capacity.

Effective public health systems require an interdisciplinary approach to public health disease surveillance, prevention, and control. Given that approximately 75% of emerging human infectious diseases are zoonosis-related,1 veterinarians are critical partners when addressing public health challenges, especially considering emerging pathogens that might have a zoonotic component (e.g., avian influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and Ebola hemorrhagic fever).2,3 Veterinarians in state, federal, and uniformed services often fill these roles; in 2006, a total of 3,312 (3.9%) of 84,946 U.S. veterinarians were employed in public health (i.e., government and uniformed service employees).4

Although veterinarians engaged in public health activities traditionally have worked in a regulatory capacity on animal health problems affecting agriculture, plant and animal health, human and animal food safety, biologic and homeland security, and wildlife and zoonotic disease prevention and control,3 others have sought to work in applied public health roles usually associated with medical doctors, nurses, and people trained in epidemiology. In addition, veterinarians in public health careers have not limited themselves to the zoonotic pathogens and often apply their population medicine knowledge to other roles of human disease or injury prevention and control, environmental health, and vaccine-preventable diseases.

A 2006 report by the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC) identified a shortage of ≥1,500 veterinarians fulfilling public health responsibilities; by 2020, this shortage is expected to increase tenfold.5 The 2007–2008 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Preventive Medicine Fellows (PMFs) conducted a veterinary public health workforce focus group project by using the community mobilization and group facilitation skills learned in the PMF training program.6 The objective of this project was to gain insight into key areas of recruitment and retention that might reduce the national shortage of public health veterinarians.

METHODS

The PMFs conducted a focus group by using a structured community intervention technique.7,8 Participants were recruited for the focus group and a SurveyMonkey™9 questionnaire was disseminated through the 2008 U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) and civilian CDC veterinary electronic mailing lists. Participants were asked to complete the survey within two weeks and before the focus group. The survey asked two open-ended questions about the nation's veterinary public health workforce (i.e., veterinarians working in both federal and nonfederal public health roles): (1) What specific problems does CDC face when actively developing the veterinary public health workforce? and (2) What specific problems does CDC face when supporting veterinarians engaged in public health practice? Participants could list up to three problems, which were considered unique responses, for each of the two questions.

PMFs reviewed the survey responses from each of the two questions and classified responses for each question into themes before conducting the focus group. Focus group participants prioritized each theme from 1=least important to 5=most important. PMFs used the weighted categorized results to assess national veterinary public health workforce problems pertaining to recruitment (Question 1) and retention (Question 2); all analyses were performed using Microsoft® Excel®.

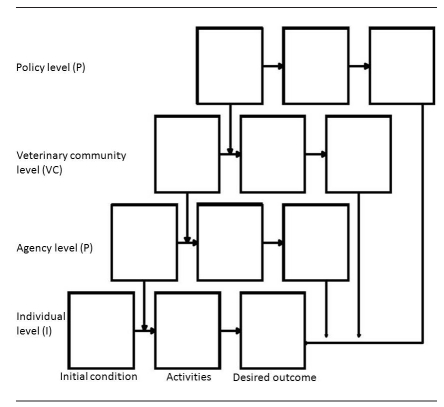

To address the top three ranked categories for Question 1 (recruitment), focus group participants were asked to identify activities by using an ecologic model flow diagram at the individual, agency, veterinary community, and policy levels. The flow diagram was designed on the basis of the ecologic model framework to identify action steps during public health community intervention processes (Figure).8,9 Activities at each of the higher levels (agency, veterinary community, and policy) were used to address the intervening concerns at that level that might prevent the main goal from being achieved. An example of an intervening factor is when an agency goal is to increase veterinary pay after completion of five years in the workforce, but a conflicting agency policy prevents the stated pay increase. Because of time constraints, focus group participants did not fully develop the ecologic model flow diagram to address priorities identified in response to retention (Question 2); therefore, these priorities are not described in this article.

Figure.

An ecologic frameworka implemented among focus group participants identifying potential strategies to address veterinary public health workforce recruitment and retention issues at the individual, agency, veterinary community, and policy levels: Atlanta, Georgia, 2008

aThe first row at the individual level indicates the initial condition to be addressed, activities that would address the issue, and the overall goal. Each subsequent higher row indicates the intervening factor that would prevent the activity at the lower level, activities to address the intervening factor, and the sub-goal that supports the overall goal in the lower right-hand corner of the figure. Permission given by Robert Goldman, PhD, MPH, MA, Indiana University School of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, Bloomington, Indiana, to use the ecologic model framework.

RESULTS

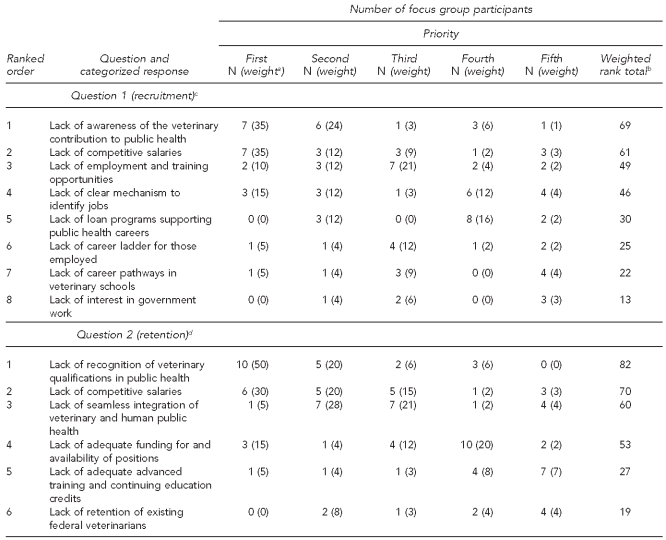

Twenty-six (29%) of 91 CDC veterinarians participated in the project. Nineteen CDC veterinarians participated in the survey, 20 participated in the focus group, and 13 participated in both. For Question 1 (recruitment), we classified the 26 unique responses into one of eight themes based on participant responses, as follows: awareness of veterinary contributions to public health, interest in government work, employment and training opportunities, a clear mechanism to identify jobs, loan programs supporting public health careers, a career ladder for those employed, career pathways in veterinary schools, and competitive salaries. In response to Question 1 (recruitment), focus group participants identified the top three problems faced when addressing this question—lack of awareness of the veterinary contribution to public health, lack of competitive salaries, and lack of employment and training opportunities (Table 1).

Table 1.

U.S. public health veterinary workforce recruitment and retention issues as identified and prioritized by a focus group of veterinarians employed by CDC: Atlanta, January 17–April 22, 2008

aIndividual calculated weight or the number of participants multiplied by the point value of the priority. The point value for each priority is as follows: first = 5, second = 4, third = 3, fourth = 2, fifth = 1.

bSum of all individual calculated weights in row

cWhat specific problems does CDC face when actively developing the veterinary public health workforce?

dWhat specific problems does CDC face when supporting veterinarians engaged in public health practice?

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Similarly, for Question 2 (retention), we classified the 22 unique responses into one of six themes, as follows: recognition of veterinary qualifications in public health, seamless integration of veterinary and human public health, adequate funding for and availability of positions, adequate advanced training, competitive salaries, and retention of existing federal veterinarians. In response to Question 2 (retention), focus group participants identified the top three problems faced when addressing this question—lack of recognition of veterinary qualifications in public health, lack of competitive salaries, and lack of seamless integration of veterinary and human public health (Table 1).

Related to the top three identified priorities for Question 1 (recruitment), participants identified activities at the individual (I), agency (A), veterinary community (VC), and policy (P) levels. To improve awareness of the veterinary contribution to public health, at least one key activity was identified at each level above individual, including increasing opportunities for veterinarians (A); educating veterinarians and other public health practitioners on veterinary contributions (A, VC); engaging the veterinary community in educating the public health workforce on the role of veterinarians (A, VC); and gearing veterinary school programs toward support of public health careers and activities (VC).

To improve employment and training opportunities, key activities identified included increasing the number of trainees in existing CDC programs (A), increasing the number of career advancement programs and guidance for veterinarians (A), identifying public health champions at each of the veterinary colleges (VC), and identifying more opportunities for veterinarians (VC). To improve the salaries of veterinarians in public health positions, key activities identified included obtaining agency support for parity in pay with other doctors of medicine (A), working across civilian and military personnel systems to achieve parity in pay for veterinarians (VC), and obtaining support from the U.S. Congress to increase pay for veterinarians in federal service (P).

DISCUSSION

Policy proposals that improve training opportunities for veterinarians in public health, increase pay, and support integration of human and veterinary public health might have the greatest impact on reducing the national shortage of public health veterinarians. Policies that increase the number of veterinarians engaged in existing or new training programs are needed to expand the veterinary public health workforce.

Federal agencies offer limited public health training for veterinarians, which alone might not be sufficient to improve the deficiency in the veterinary public health workforce. For example, veterinarians compete and are selected by CDC to participate in the CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) and PMF programs.6,10 According to the CDC EIS Program Director, the EIS program trained an average of seven veterinarians annually during 1990–2008 (Personal communication, Douglas H. Hamilton, CDC, September 2010). During that same time frame, after completion of EIS, zero to three veterinarians were trained each year in the PMF program. Even if the EIS program trained veterinarians exclusively (i.e., 80 veterinarians per year), the number would be insufficient to address the country's ongoing and anticipated veterinary public health needs.7

Veterinarians might also be required to obtain additional education at substantial expense before being considered for a federal public health position. For example, before applying to the CDC EIS program, veterinarians are required to hold either a master of public health degree or an equivalent degree, or demonstrate prior public health experience.10,11 With veterinary school tuition often higher than medical school tuition (yearly median tuition was $22,761 and $20,135 for veterinary school tuition and medical school, respectively, for in-state residents during 2008–2009) (Unpublished data, AAVMC comparative data report, 2008),12 and with starting salaries substantially lower than those of physicians, veterinarians might not be able to afford to pursue a public health career without added incentives. The average educational debt among graduates from veterinary medical school was $129,976 in 2009, an 8.5% increase from 2008.13

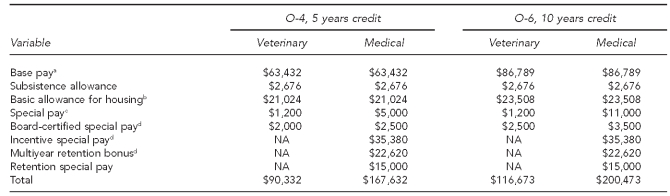

Increasing pay can reduce this additional financial burden and make public health positions more accessible for veterinarians. PHS veterinary officers are eligible to receive minimal additional pays (i.e., $266–$308 per month for board certification and $100 per month special pay). The special pay for PHS veterinary officers has not increased since it was established for unified service veterinarians in 1949.14,15 Even when employed by the same agency and filling an equivalent position as PHS medical officers (i.e., physicians), PHS veterinary officers are ineligible for special pays that might be used as a recruitment and retention tool among veterinarians. These special pays include variable special pay, incentive special pay, multiyear retention bonuses, and retention special pays.15,16 In 2011, considering the maximum of all special pays and allowances available for a PHS officer board-certified in preventive medicine (employed in a position not requiring direct patient care) at the O-4 (i.e., Lieutenant Commander, which might be comparable to a person holding a GS-12 or GS-13 position) temporary rank with five years of credit based on base pay and creditable service entry dates, living in Atlanta, Georgia, with dependents, the veterinary officer earned an annual salary of approximately $90,332 and the medical officer earned approximately $167,632 (Table 2). Similarly, among O-6 (i.e., Captain, which might be comparable to a person holding a GS-14 or GS-15 position) temporary ranked preventive medicine board-certified officers with the same duty station and dependent status who have 10 years of credit based on base pay and creditable service entry dates, approximate annual salaries were $116,673 for the veterinary officer and $200,473 for the medical officer (Table 2). In these examples, the pay differentials between the veterinary and medical officers are primarily attributable to the maximum variable special pay, incentive special pay, multiyear retention bonus, and retention special pay for medical officers, which totaled $77,000 for those with five years of creditable service and $84,000 for those with 10 years of creditable service.

Table 2.

A comparison of the approximate maximum eligible annual incomes of preventive medicine board-certified U.S. Public Health Service veterinary and medical officers with dependents living in Atlanta, Georgia, by temporary rank, and years of credit per base pay and creditable service entry dates, 2011

aBase pay is reported according to 2010 military pay table rates (http://dfas.mil/miltarypay/militarypatytables.html) and calculated using base pay entry dates.

bBased on 2011 pay table rates for Officers with dependents stationed in Atlanta, Georgia (https://www.defensetravel.dod.mil/site/bahCalc.cfm)

cConsidered variable special pay for Medical Officers

dAssumes the common tier four-year contract rate for Medical Officers claiming preventive medicine specialty; multiyear retention bonus rates are less for two-year ($8,120/year) and three-year ($15,660/year) contracts.

NA = not available

PHS pay for veterinarians is not competitive with other employment opportunities. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, in 2007 the median income among private veterinary practitioners was $91,000; among board-certified veterinary specialists in private practice, the median income was $167,862; and among veterinarians in public or corporate practice, the median income was $140,893.17 During 2009, starting salaries among public-corporate sector veterinarians decreased 7.3%, compared with a 6.0% increase among veterinarians employed in private practice.13 Furthermore, the U.S. Department of Defense increased the pay (maximum of $16,000/year in additional special pays effective October 2009) for active-duty veterinary officers.18

Expanding recognition of veterinarians' -contribution to public health can create interest in and improve the number of veterinarians serving in public health positions. Advocating veterinarians' abilities can raise their profile, broaden the range of positions open to veterinarians, and change attitudes about what should be considered appropriate professional work for a veterinarian, expanding commonly held beliefs. Veterinarians often successfully fill nontraditional public health roles across local, state, and federal agencies. For example, veterinarians have served as the state epidemiologist for Georgia and as acting U.S. Surgeon General.3 Conversely, veterinarians with the requisite training and experience have been limited in the types of positions for which they are allowed to apply. For instance, veterinarians are excluded from applying to federal public health positions not requiring direct human patient care (e.g., epidemiologist) listed on USAJobs®19 under the General Schedule 600 series (human medical). Focus group participants recommended advocacy efforts at the national level to ensure that hiring efforts allow for veterinarian employment in public health positions not requiring direct patient care.

Results from this focus group demonstrate that more appreciation and understanding of the roles public health veterinarians fill can help expand veterinary public health capacity. Increasing recognition by prospective veterinary students that career options exist beyond the traditional confines of private clinical practice can make a veterinary career more attractive to those who otherwise might select different professional training. Raising the public profile of veterinarians can serve dual objectives identified by this focus group, such as reducing barriers and developing and increasing the veterinary public health workforce (i.e., the need for recruiting new candidates to address the growing need for public health veterinarians and concurrently improving the lack of awareness of the veterinary contribution to public health).

Limitations

There were three main limitations in this study. First, we were unable to fully develop the ecologic models because the focus group activities were limited to one 2.5-hour session. Despite this constraint, we believe that this project identified key problems that have been voiced anecdotally by other veterinarians employed in public health.

Second, this project was conducted only among a limited number of veterinarians living in Atlanta who were employed by CDC. Feedback from additional CDC veterinarians, veterinarians at other federal agencies, federal veterinarians who are assigned to states, and state-employed veterinarians might have resulted in different concerns and additional proposals. On the basis of anecdotal information from project participants, however, we are confident that this project identified key problems that can be identified if repeated in another venue.

Third, demographic and experience data were not collected; therefore, we were unable to stratify concerns identified by number of years and types of experience. However, project participants represented veterinarians with <5 and >15 years of public health experience, veterinarians with experience working for other federal agencies (e.g., the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety Inspection Service), and veterinarians employed by the PHS and civil service.

CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this pilot project was to identify concerns and potential policy strategies to address the U.S. veterinary public health capacity shortage. Despite the limited number of participants and the need for additional studies with a broader audience, this project identified key problems that are likely to be voiced by veterinarians at all levels of public health employment (e.g., local, state, and federal). Results from this project can serve as a platform for change and a base on which future projects and initiatives can be built; engaging the general public, policy makers, and government management officials will be required to address the identified concerns. For example, this article might help influence policy makers to increase pay for public health veterinarians by using mechanisms that have been established for the U.S. Department of Defense18 or to establish mechanisms to recruit and retain veterinarians in the PHS similar to what has been established for physicians.16 A committed and determined long-term effort will be required to sustain initiatives and policy proposals needed to increase the U.S. veterinary public health capacity.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following people for their contributions: Hugh M. Mainzer, MS, DVM, Dipl. ACVPM, Chief Veterinary Officer, Captain U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Centers for Environmental Health, Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services in Atlanta, Georgia; Walter R. Daley, DVM, MPH, Dipl. ACVPM, Captain USPHS, CDC, Scientific Education and Professional Development Program Office, Epidemic Intelligence Service Field Assignments Branch in Atlanta; Mehran S. Massoudi, PhD, MPH, Captain USPHS, CDC, Scientific Education and Professional Development Program Office, Office of the Director in Atlanta; Cheryll K. Smith, MEd, CDC, Scientific Education and Professional Development Program Office, Office of the Director in Atlanta; Li-lien Yang, MS, CDC, Scientific -Education and Professional Development Program Office, Preventive Medicine Residency and Fellowship in Atlanta; and Amanda K. Dunnick, MPH, Commander USPHS, CDC, Commissioned Corps Personnel Office in Atlanta.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaddock HM. Washington: Association of American Veterinary Colleges; 2006. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Veterinarians: integral partners in public health. Also available from: URL: http://www.onehealthinitiative.com/publications/VWEACongressionalPaperPDF.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappaioanou M, Allen SW, DeHaven WR, Kelly AM. Testimonies on the Veterinary Public Health Workforce Expansion Act of 2007 (H.R 1232) presented before the subcommittee on health of the United States House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce, January 23, 2008. J Vet Med Educ. 2008;35:439–48. doi: 10.3138/jvme.35.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Veterinary Medical Association. Market research statistics: U.S. veterinarians—2006. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.avma.org/reference/marketstats/2006/usvets_2006.asp.

- 5.Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges. Veterinarians step up to the nation's public health needs. Washington: AAVMC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Preventive Medicine Residency and Fellowship. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/prevmed.

- 7.Yoo S, Butler J, Elias TI, Goodman RM. The 6-step model for community empowerment: revisited in public housing communities for low-income senior citizens. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:262–75. doi: 10.1177/1524839907307884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman RM. Bridging the gap in effective program implementation: from concept to application. J Commun Psychol. 2000;28:309–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.SurveyMonkey Inc. SurveyMonkey™. Portland (OR): SurveyMonkey Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/eis/index.html.

- 11.Thacker SB, Dannenberg AL, Hamilton DH. Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 50 years of training and service in applied epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:985–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Association of American Medical Colleges. Public medical schools—tuition and fees first year medical students 2008-2009. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://services.aamc.org/tsfreports/report.cfm?select_control=PUB&year_of_study=2009.

- 13.Shepherd AJ. Employment, starting salaries, and educational indebtedness of year-2009 graduates of US veterinary medical colleges. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235:523–6. doi: 10.2460/javma.235.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 37 U.S.C. §303 (1949)

- 15.Public Health Service (US) Subchapter CC22.2—special pays. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://dcp.psc.gov/eccis/documents/CCPM22_2_1.pdf.

- 16.Public Health Service (US) Fact sheet for completing medical special pay (MSP) contract. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://dcp.psc.gov/MSP_fact_sheet.htm.

- 17.America Veterinary Medical Association. AVMA survey measures income trends to 2007. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/jan09/090101a.asp.

- 18.Department of Defense (US) Directive-type memorandum (DTM) 09-009: implementation of special pay for health professions officers (HPOs) Washington: Secretary of Defense; 2009. Jul 23, [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Also available from: URL: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/DTM-09-009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Personnel Management (US) USAJobs®. [cited 2010 Oct 6]. Available from: URL: http://www.usajobs.gov.