Abstract

Background

Access to water is a right and a social determinant of health that should be provided by the state. However, when it comes to access to water in rural areas, the current trend is for communities to arrange for the service themselves through locally run projects. This article presents a narrative of a single community's process of participation in implementing and running a water project in the village of El Triunfo, Guatemala.

Methods

Using an ethnographic approach, we conducted a series of interviews with five village leaders, field visits, and participant observations in different meetings and activities of the community.

Findings

El Triunfo has had a long tradition of community participation, where it has been perceived as an important value. The village has a council of leaders who have worked together in various projects, although water has always been a priority. When it comes to participation, this community has achieved its goals when it collaborated with other stakeholders who provided the expertise and/or the funding needed to carry out a project. At the time of the study, the challenge was to develop a new phase of the water project with the help of other stakeholders and to maintain and sustain the tradition of participation by involving new generations in the process.

Discussion

This narrative focuses on the participation in this village's efforts to implement a water project. We found that community participation has substituted the role of the central and local governments, and that the collaboration between the council and other stakeholders has provided a way for El Triunfo to satisfy some of its demand for water.

Conclusion

El Triunfo's case shows that for a participatory scheme to be successful it needs prolonged engagement, continued support, and successful experiences that can help to provide the kind of stable participatory practices that involves community members in a process of empowered decision-making and policy implementation.

Keywords: community participation, community organization, water projects, Guatemala, social development councils

Over the past 40 years, community participation became an important component of public health and social development policies. The interest in it comes from the perception that community participation tends to make projects more acceptable and sustainable for beneficiaries and more cost-effective for donors (1, 2). The ideal purpose of community participation is that it will contribute to improving inclusion levels in policy-related decision-making process, which will lead to a redistribution of power that will enable community members to have a real say in the policies that affect their everyday lives (2, 3).

Community participation in public health is one of the central themes of the primary health care (PHC) approach, which was first popular in the late 1970s, but that now enjoys a renewed sense of importance because of the 2008 World Health Report and the ‘call back’ to Alma-Ata currently being promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO) (4). The goal of participation in PHC is to make the health system more responsive to local-level needs and to address the underlying structural aspects that promote inequality in both obtaining health services and leading a healthy life (5, 6). Community participation is a way to face resource constraints, power imbalances, and a lack of support from higher levels of the health system when it comes to participating in the policy process (3).

The 2008 report by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health recognized that community participation in health policy is not enough to improve a community's health status. Participatory practices should be included both at the health system level and in interventions related to the environmental factors that determine health (7). One of these determinants is safe water. Because of its impact on a population's mortality/morbidity and overall quality of life, much pressure has been put on policy makers to improve access to safe drinking water. As a result, there have been numerous policies, institutions, and civil society organizations put in place (5, 8). Governments have the responsibility to provide their citizens with the necessary conditions for them to enjoy the right to safe and clean water (9, 10). However, in developing countries the growing trend in water policies is for community-level stakeholders to carry the bulk of the responsibility for the functioning and for the service provision of water projects. Many of these locally driven water projects started as a way to ensure this access to safe water, and they constitute an example of how community leaders, donor agencies, and governments work together to provide a service that is expected to be run at the community level (1).

Although community participation has been promoted by international agencies as crucial for development of health and its determinants, the literature is scarce on community leaders’ own experiences of mobilizing community resources. The aim of this article is to explore the meaning of community participation in the context of implementing and running a water project in rural Guatemala. To do it, we present a narrative that recounts the story of the members of the social development council in the village of El Triunfo, Guatemala. We present the historical and social context of the story by including a brief overview of the 20th century, of the participatory scheme currently in place in the country, and of the main policies regarding water. The narrative approach used in the article allowed us to give a voice to the storytellers and to understand their process of community organization and the role that community participation has in it for them.

Background

Guatemala

Historical context of the narrative

Like other Guatemalan communities, the members of El Triunfo saw the major political and social events of the 20th century from the backseat. Over the course of the 100 years between the original settlement in 1908 and the series of interviews that form the narrative presented in this article, in 2009, much has changed for the members of this community. Interestingly, organization and community participation were the key themes in every major milestone mentioned in this story.

When the families that make up El Triunfo first settled on the land where they live now, in 1908, Guatemala was a country ran by a liberal totalitarian government. It was in the context of consecutive dictatorships that the community members first gained the rights to their land. A coup d’état in late 1944 started the decade of the Revolution, and a new constitution banned forced labor and idle land. It also gave citizens social rights to health, work, and education for the first time. By the end of this decade, Guatemalan society had undergone profound social and cultural changes, but a coup in 1955 interrupted the democratic regime and started the series of events that would lead the country into 36 years of armed conflict (11).

In the 30 years between the 1955 coup and the elections of 1985, the government abolished all workers’ unions and political parties, and all forms of local or political organization were considered dangerous. (12). The extremely restrictive and violent policies set in place by the military governments of this period, combined with the cold war and pro-communists movements elsewhere in Latin America, provided grounds for guerrilla groups. Through both urban and rural confrontations, the military and the guerrilla groups together tallied about 200,000 victims of murder, kidnapping, torture, and rape (11, 13).

It is in the context of this repression and violence that two milestones in El Triunfo's community organization happened. The first one was the creation of a National Reconstruction Committee as a way to rebuild the country after the devastation of the 1976 earthquake. This national committee had local, community-based committees in charge of rebuilding, cleaning up debris, and distributing food and medicine where the earthquake had hit. The second milestone was the creation of the patrolling groups in the late 1970s and early 1980s, constituting of all able-bodied men in a community, who had to volunteer to patrol against the ‘communist threat’ (11). In a sense, this provided a structure of community organization beyond rebuilding and distributing donations.

Several different political and social changes led to the first democratic elections in 1986. During this government, policies on community participation started again with a first version of the social development councils that is now in place. These policies were fueled by an increase in foreign aid, a temporary decline in violence levels, and a hope for a better future. However, by the end of the 1980s, the council system had stopped working and the political violence levels increased again (11, 13).

After several years of slow negotiations, the armed conflict ended with the peace agreements of December 1996. In them, the state committed itself to an ongoing decentralization process that would promote community participation as its main policy (14). The Guatemalan congress passed a legal framework for decentralization and community participation in 2002 in order to promote and back up both policies.

The social development council system

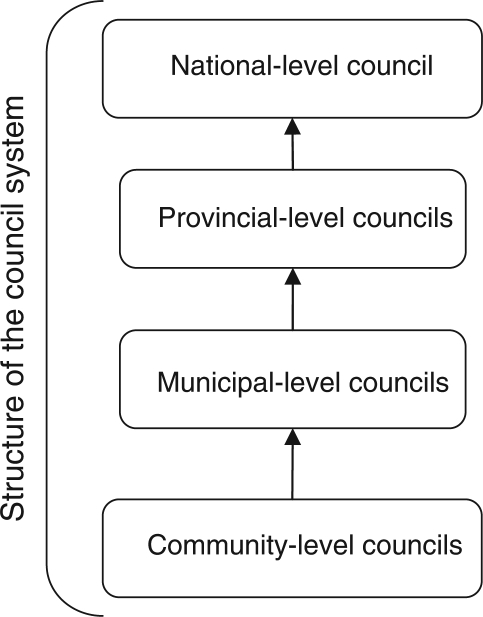

Guatemala's participation scheme is a bottom-up structure based on the rights of all the population to be included in decision-making processes for the policies that affect their everyday lives. The council scheme is organized as a multi-tiered system where the national, provincial, and municipal levels mirror the country's political organization structure (15) (see Fig. 1). In all three levels, there is participation from government representatives, elected officials, and from civil society members (15–17).

Fig. 1.

The Guatemalan social development council structure. Source: Authors elaboration from the Rural and urban social development council act of 2002.

Community-level councils consist mainly of community representatives who are elected or appointed by the community for a renewable two-year period. Their role is to identify their community's needs and priorities, and to participate in the formulation, planning, implementing, monitoring, and evaluation of projects and policies that affect them or their community at the community and at the municipal level. They are recognized as organizations with legal power and special rights, and are expected to play a key role in the social development process as leaders of their communities (15).

Water policies

Guatemala has enough water to supply all of its population, but poor administration, pollution, inappropriate use, and wastage mean that only 47.91% of the rural population (compared with 87.34% of the urban population) have a water connection in their homes (18). The lack of clear guidelines and policies regarding the management of the resource results in a lack of availability and unsatisfied demand, in addition, misuse of water creates a strong pressure on the existing sources and makes the current system unsustainable (18, 19).

According to the country's constitution (17), all of the water sources are public and should be managed in a sustainable way. However, so many organizations have the responsibility to regulate, distribute, oversee, or organize the provision of water to the population that the system is fragmented and complicated, and without a specific framework, there is no appointed steward or regulator (19). The existing policies are filled with duplicated, empty, or obsolete articles and do not provide a structure for the system; therefore, knowing the rights and obligations of any stakeholder is almost impossible (18). According to the municipal code (16), each municipality has the obligation to provide and administer waterworks; yet, at the rural community-level, most water projects are locally run by their council (18).

For Cobos (18), the Guatemalan experience with community-level water projects has been a positive one because when communities are involved, the projects are more successful and tend to be more sustainable. Still, because of the way the water sources are managed, and of the changes to the natural cycle of dry/rainy seasons that come with climate change, it is estimated that by 2030, 50% of the country's resource will be unsuitable for human consumption.

Methods

The setting

The village of El Triunfo is located in the municipality of Palencia, which is part of the Guatemala province. In total, Palencia has a population of 55,410, and 99% of the population does not belong to any of the indigenous groups in the country. Of them, 70.3% live in rural villages like El Triunfo, and of the total population, 38% are poor (20, 21). Most of the population that live in Palencia's urban areas have regular access to drinking water and electricity (70%). However, the remaining 49 communities have little or no access to municipal services (22).

The village of El Triunfo is a tight-knit farming community of about 110 families who rely on a mixture of subsistence farming and growing coffee to meet their needs. Most families own small parcels of lands and their own homes, and most of them have lived there their whole lives. When it comes to access to water, most homes have a tap or some manner of indoor plumbing, but the supply from the village's water source is not sufficient to provide a steady and reliable service. Because of this, each house only gets water for a few hours every other day and the project's only plumber is in charge of regulating this supply. Storing water during the night to ensure a better and more stable supply is also impossible because the community does not have an overnight containment tank.

El Triunfo's community-level social development council has been active since the country started this scheme of participation in early 2003. During the time of the fieldwork, the council had four members and the deputy major was working very closely with them. The council members, Don Octavio, Don Miguel, Don José, and Don José A., and the deputy mayor Don Roberto have been participating in their community for more than 30 years. In that time, they had taken turns in being the community's deputy mayor, in being part of the council or committee in place, or in being other official figures that represent the community. The council members and Don Roberto are all men in their mid-to-late fifties, married and with grown children. They had lived in El Triunfo all their lives, as well as raised their families there. They are considered the village's elders and have close family and religious ties to most families in the community. Like most of the people in El Triunfo, none of them finished primary school. During 2009, Don Roberto split his time between being the deputy mayor of the community, working on his land and volunteering in different community projects. Don José and Don Miguel acted as part of the community-level social development council, worked on their own land, and were very active in their respective churches. Don José A. and Don Octavio attended all of the group interviews and contributed off the record but chose not to participate in any recorded conversation.

Narrative methodology

This paper presents and analyzes a narrative about community participation from the community of El Triunfo. According to Riessman (23), narratives allow persons to recount and reflect on a sequence of events that create a sense of belonging and builds identity. Through storytelling, the actions of the teller or a group are justified and presented in a way that lets hearers understand the motivations behind a specific process or action (23, 24). By using narrative analysis, we were able to capture the meaning that the community participation process had for this group of men and understand how it contributed to change and improvement in El Triunfo. Finally, it also allowed us to understand how the process expressed their shared values of trust and solidarity to their community. Analyzing their story allowed us to identify the roles, the process, and the perspectives that lead to understanding the meaning that participation had to the council members, and how the events and values all link into a bigger story (25, 26).

Data collection and analysis

The first step of our data collection process was to contact the members of El Triunfo's community-level social development council to present our project and to explain our methodology and the reasons for wanting to hear and analyze their story. The collaboration with the council for this, and for a previous study, was part of a doctoral research project studying the role of social participation in the municipality of Palencia that had started in January 2009 and involved work with municipal-level and community-level councils, and with the municipality's community health workers. The council members of El Triunfo already knew the first author (ALR) and were familiar with the larger project that frames this study as well as open to participate in this one.

After initial contact, four different group interviews with all the members of the council were held between the months of June and August 2009. In order to improve the richness of the interviews, each session was conducted in a different part of the village using the community's landmarks as memory aids (23). The first and the second interview occurred in the village square, where the school building and the trees planted there helped the council members recall the changes that occurred throughout the years. The third interview consisted of a walk to the village's three water sources. The closing interview happened in the village's meetinghouse and consisted of recalling and reorganizing the events, as well as reflections on the council member's reasons to participate and get involved in the different councils.

All the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed on the same day they were held, and the transcriptions, observations, and field notes served as guides for the topics to be discussed on the following sessions and as context information for the discussion and conclusion sections. After the fieldwork was done, the authors edited the narrative together according to the timeline that the council members described. Although narratives are chronological in nature, when they are a part of a series of interviews the tellers rarely start ‘at the beginning’ and finish ‘at the end’ (24, 26). Finally, we constructed a timeline with the main social and historical milestones of the country to analyze the narrative using the national history as a reference.

Ethical considerations

In Guatemala, only researchers conducting clinical trials or human testing are required to obtain ethical clearance from any committees. However, we took steps to procure ethical clearance by contacting and informing the municipal authorities about our project, and by describing our research goals, methodology, and outcomes with the members of El Triunfo's community-level social development council. We obtained verbal informed consent from all the members of the council individually. They all agreed to allow ALR to record the group interviews, to take notes, and to use both their names and the village's name in this article.

Findings

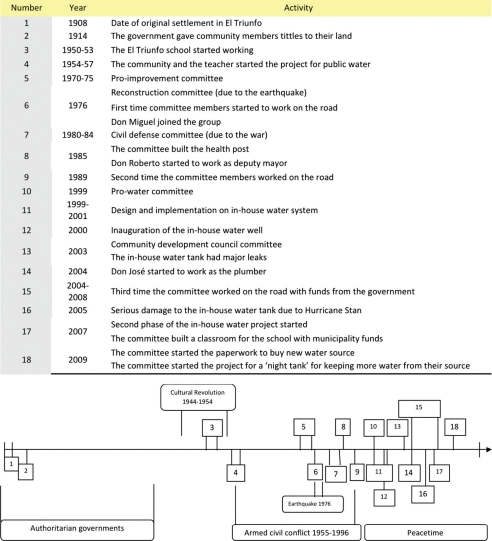

In this section, we present both the story of El Triunfo's process of community organization and participation in regard to their water project and a timeline. Fig. 2 presents a summary of the major historical events in the country, which serve as contexts for the village's milestones. Afterwards, the El Triunfo council members’ story is presented and divided into sections, with some introductory commentary from the first author. The purpose of doing this was to unify all four of the group interviews while making ALR's role in the interviews more evident (23).

Fig. 2.

Timeline and major milestones in community organization and participation in El Triunfo. Source: Authors’ elaboration from Luja′n Muñoz, 2004 and collected data.

The story

How El Triunfo settled

Here, Don Roberto remembered how El Triunfo was first settled. He brought it up as an example of his community's commitment to participating and of what the members of El Triunfo can accomplish if they work together:

‘This was a farm that belonged to the Montenegro family. But over there, in that valley, there were some people from the neighboring jurisdiction of El Tambor and they started to fight. No one lived here, no one. People thought it was not fair that only Montenegro's cattle used that land so they joined together and organized themselves, and there is where we see that unity is strength. And these people persevered so that the government could separate some of that land and donate it to El Triunfo. They were successful and they continued to fight for about two or three years, so that in 1914 we planted this Ceiba tree. Imagine that the Morral tree there [was planted] in 1914 along with the Ceiba. This tree came from Sanarate and was already here when we grew up. I remember I was 10 when we came to school, and that building was made of adobe. And there was a Nance tree there and that was a little hill. There was another one there and this whole place had Jacarandas around it. We cut down the Jacaranda trees so we could play ball, because we didn't have a place to play.

The original water project

This section comes out of an interview conducted during a visit to the El Triunfo's water sources. Chronologically, it takes place before any of the current members of the council could get involved in community matters, as they were young children when this happened. Don Miguel mentions that he found out about this part of the project when he was doing some research for the in-house water project they had in the early 1990s:

That was the first one [water source], and it's like fifty years old … I don't know how they found that. The water's been there for a long time [and] people would come to get it here... around that time a teacher came and saw the need we had and said well, we can get materials to get the water here and let's see who can give us a spring. Then a guy called Magdaleno Estrada, who was the owner of the land where the spring is, said ‘I'll give you the spring’ and that's how the teacher and her husband persevered and got the project with some money for materials from the government.

It was 1954 when the water came to El Triunfo. The people were happy. Although as we said, there has always been some problems because even though the community was small, not everyone wanted to participate. I myself had the opportunity [to see this] when we were about to change the pipes [and expand the in-house water project] and I needed to go to the school to ask the teacher for the original protocol from that project and I got a copy that mentions everyone that participated and states who didn't want to. This is why I say that the project belongs to the community and we benefit greatly from it.

Organization and community work during the earthquake of 1976

An earthquake hit the country in February 1976 (see number 6 in the timeline). In order to start rebuilding, the reconstruction committees started working later that same year. Using the special financing and supplies, the committee from El Triunfo gained its final member, Don Miguel. Here, Don Roberto and Don Miguel explain how their community benefited from these policies.

Don Roberto:

[Due to the earthquake], there was a reconstruction committee that was very important here in Palencia. We really benefited from that and that time brought us a lot of community work because we would get goods in exchange for our labor. The government worked like that, helping the rural areas. We got food in exchange for fixing the road … and by then Don Miguel joined in.

Don Miguel:

It was a reconstruction committee and that's when we started working on the school.

Patrolling during the war

The very high levels of violence that existed throughout the conflict hit their peak in the beginning of the 1980s. As a way to control ‘the communist threat’, the state organized volunteer citizen patrols that had to provide time and weapons. In one of the interviews, first Don Roberto and then Don Miguel told me about this:

You know what they made us do? Patrol! And we knew that the war wasn't here. It was around 1985, well, before that … and we started to patrol, we organized ourselves into groups of ten and then we slept! There was no war here, thank God this was a safe area.

… [Although] we couldn't really be out in the open, [I mean] how were we to defend ourselves? We had no weapons, all we had were our machetes [but] it was quiet around here.

Democracy and deputy mayors come to El Triunfo

After more than 20 years of de facto governments and coup d’états, the country finally had a free election in 1985. With this ‘return to democracy’, donations and foreign aid came into the country to help rural and excluded populations. Here, Don Roberto and Don José recount how they built the health later in their community. It was during this time that Don Roberto started to work as deputy mayor.

Don José:

[We built the health center] in 1985 [when] a woman … from the Peace Corps, called Margaret, supported us and gave us ten thousand Quetzales and with those ten thousand we build that … we were all involved in that by ‘85. This is when I started to work as a leader of this community. Don José was the chairperson for our committee and then we started to work. That was our initiative and Don José was elected by the community.

Everyone should have water in their own home

This part of the narrative, which sums up the group's work from the 1990s to the early 2000s, shows how the group focused on fixing the road that leads to El Triunfo and on the first in-house water project. The process of the first stage of the water project took several years. During this time, the group learned how to make maps, and both bought land and the water source as a community. During all of the group interviews, Don Miguel, Don Roberto, and Don José talked about the process of getting the road and the water project built and funded. Don Miguel recounts that the water committee ended, but that community participation did not stop:

First, we did a sketch of the community … We went from one house to the next and did the whole thing. Then we presented our ideas to an institution funded by Spain … they took the responsibility and paid for the labor and the materials. [We] followed all the process and guidelines and that took about two or three years, until we got our aid approved. The land we bought ourselves, as a community. The ones from the institution gave us the materials and assessed us with the design and everything until we finished it. We only provided community labor and bought the spring that was about Q25,000 The institution didn't want the municipality to intervene so that they could not take the project away from us with a tax. That's why we paid for the spring ourselves.

After that, we worked with one of the archdioceses’ institutions [so we could fix the road]. They gave us food in exchange for our work. I was telling you that our road was terrible … we fixed it over several years. Forty people would volunteer once a week, on Mondays. The road is about eight kilometers long and we wanted a bus to come here [but] its tires would rip apart in the stones so [we] would organize ourselves and volunteer to upkeep it. We worked hard on the road for a long time and we asked for pipes and achieved a goal for our community: the high part [of El Triunfo] really needed water and so we got them water with underground pipes that the municipality paid for. [Before], they couldn't get drinking water because the low part of the community used it. So we helped them and now we share [the water]. We also improve our communal roads and talk to people so we can be better. We all work together as a good team.

The water committee's work finished before 2003, when we installed the new water project. In April of 2003, we started to promote the community-level social development councils and Octavio went to the Ministry of the Interior at the same time when everyone was promoting the councils and so the council took shape and we were elected.

An official name for participating in our community

In late 2002, the Guatemalan state passed several laws about community participation and the social participation scheme working at the community and in the municipality of Palencia in early 2003. Here, Don Roberto, Don José, and Don Miguel told me how they started to work as a legally recognized council, about the paperwork they had to do, and how this all tied in with their commitment to get enough water for all the members of their community:

Don Miguel and Don Roberto:

First, we had to go to the [municipal-level] social development council, and then we started our own council. Afterwards, we went to the Ministry of the Interior and to the municipality. We thought that just going to the [municipal-level] social development council was enough but it's not. We had to get accredited at the municipality … [and do the same] every two years. In the beginning, the people here didn't want to … didn't accept it … we even had the governor from the province of El Progreso to talk to us about it and we six got elected [and when we started to work we got told] that doing this council work requires time and money. This process has been going on for six years now. In April of 2003 we also started to coordinate our work with Don Roberto because the councils need uneven numbers. He's not a part of it, no. He is the deputy mayor and we work with him to get through the formalities and paper work because he is an authority. We only collaborate to improve the community. Don Roberto can officially call on a person and we can't. And even if we go to all the meetings, he is the one that does all the paperwork. [For this paperwork] we don't really ask for financial help from the community because people think that if they give us Q1.00 they can pressure and criticize us because they think we're stealing the money. So we much rather use our own, or borrow it. People never think you're doing a good job, they always think we do it to get something out of it.

Don Miguel and Don José:

[Now we] need to [build a new containment tank] because the water was leaking, so we built a box to hold it but it overflows. We don't have any place to store the water, so we just use it as it springs … so during the night, when no one's using it, it just flows away. So now the community and the municipality are working together to build a containment tank for the night-springing water. So, during the day we'll supply water to two parts of the community and the water from the night is for the other sectors, so everyone will benefit from this project.

We're organized and the people support us because the need for water is great. So we believe that if we achieve this project it would be like striking gold because many of us are in a lot of need and I think this is the most important project we have. To build it would be the best thing…in other words, it would be the ideal gift from the municipality because they are helping with this process and they hope to have the means to buy a new spring because it is just too expensive. We couldn't even afford to pay for half of it. So, we always tell the municipality that we need the water, even if we don't have electricity, we need water.

Reflections on the process of participation

At the end of the last group interview sessions, we talked about what community participation meant to each of them. Don Roberto, Don Miguel, and Don José spoke about both their personal and internal reasons, and of the reasons to get involved as someone that is part of a community. This first reflection is about how participation can build trust, promote agency, and have positive effects on what they perceive is the loss of values around family and community.

Don José:

Do you know what we do? All this deliquency and psychologically ill young people. Some may even have educated and well-to-do families but they don't have peace in their lives or hearts so they think that the solution is to jump off a bridge. They go around killing people left and right, and they are organized. Well, if they are organized to do evil, why can't we do it [get organized] to help people get off that bad road so that they can have a life that respects and praises God and that is in harmony with all of humankind? It is so nice to be at peace with your neighbor…but if my neighbor is an extortionist, a truant, I'd be afraid of him killing me. There is no need for that.

This second reflection links the role of participating in their own community as an individual to belonging to a group that constantly acts in the interests of all community members, not just family groups. It also presents the sense of importance and urgency that the council members have about participation, even that which happens outside of the council sphere:

There is no time to lose. In first place you have your family and then your community. This is true at a social as well as at a religious level…For the most part, our motivation comes from our needs and the enthusiasm and interest we have in improving our family and everyone else's lives. And when people say ‘let's do it’, we feel good, like when neighbors help [each other]. The motivation is our community. If no one else stands up, you have to…when you stop paying attention to [the community's lack of support], you start improving your community. We need so many things: water, electricity, roads, schools, health centers…so many things we need.

Discussion

This narrative focused on community participation in the context of one village's continuing efforts to implement a sustainable water project that has enough capacity to provide for every family in El Triunfo. Access to a regular supply of safe water is a basic human right and improving access to it might improve a community's income, its health status, and contribute to the production of food (9, 10). The role that central and local governments play in insuring and safeguarding this right should not be put aside because community-managed projects have shown to be successful in some contexts (1, 3, 18).

International treaties on human rights and the Guatemalan constitution award the responsibility of water provision to the state, who in turn delegates it to municipal governments. These state-run water services need to provide universal coverage through the sustainable management of natural resources (10, 17). In Guatemala, several municipalities like Palencia are only able to supply these services to its urban population (20). Providing enough safe drinking water is difficult when municipal governments lack funding, infrastructure, and capacity to make water readily available. However, the issue in the country is not the lack of the resource, but the structural problems preventing its equitable distribution throughout the territory and within population groups (17, 19). The state can deal with this by having comprehensive policies and by assigning clear responsibilities to all the stakeholders involved. This can help to overcome the contextual and historical reasons that put poor, rural populations find themselves in when it comes to access to water.

In the 100 years since the community of El Triunfo settled, the village has enjoyed relative stability and peace, little to null migration rates, and its population has continued to be made up of a limited number of families who live in a close-knit community. The cohesion and integration that exist in this community does not come solely from the stable environment, it is a product of the villagers’ capacity to feel connected with each other through their similarities in work, values, family bonds, and religious beliefs (26). However, there is more to this village's achievements in organization than solidarity alone. External actors have played an important role at different times during the course of the different water projects. This has allowed the village to obtain several benefits from the process, which reinforced the need for ongoing organization and participation at the community level.

El Triunfo's case might be different from others in the country and even from some in the same municipality. The outcomes of their efforts do not come from the country's guidelines on community participation, but from their own experience of working together, of sharing values, and of building a unique group through their experiences and the construction of a shared group identity based on cooperation and respect (27). In this village's case, the council scheme ‘fell on top’ of something that already existed, and the role the council scheme has played has been more of a legitimization mechanism for their work as leaders, and did not bring about any new dynamics or ways of working. Even though the country's system for participation is promising it has several shortcomings, especially in regards to its unclear guidelines and the lack of control mechanisms to ensure its correct functioning. This leads to a situation where each individual council owes its dynamic to the interaction between its members, to its specific context, and to other preexisting conditions obstructing a more uniformed and standardized system of participation throughout the country.

The study has some important limitations worth mentioning. Only stories from the council members of ‘El Triunfo’ were included. This was because we identified them as key persons that could give us in-depth knowledge of the particular experience of community participation. In narrative analysis, it is implicit that through the eyes of the teller, rich information about the perspectives, motivations, and subjective experiences can be learned. However, the stories from other community members might have given perspectives and meanings of the participation process different to the ones presented here. Since the beginning of ‘El Triunfo,’ men have been the community leaders and main communicators with the governmental authorities. Though the wives of the council members actively engaged all along, they were never part of the council board. This seems to reflect the unequal gender structure present in the Guatemalan society. The inclusion of women's voices would have highlighted different challenges of the community participatory process.

Further, the success of this water project was based on the participatory experiences of the council. We call it a successful experience because through the active participation of the council members, the community has been able to improve its overall ‘quality of life’ by having more access to water and a better road, as well as several other small projects that are not part of this story. We acknowledge, however, that there are many more factors that are not included in this paper that need to be considered before we can call El Triunfo's water project a success.

Community participation and organization are two key themes in the lives of the community-level council members in ‘El Triunfo,’ and they stem from both individual, internal reasons, and group motivations for getting and staying involved. As a group, their work was not always completely supported by the community, but their belief that participation improves the village and the lives of everyone in it has led them to become and stay involved, and even investing their own time and money. This way they have been able to create something bigger than themselves, as they have managed to achieve long-standing goals such as fixing the road or planning, implementing, and running the water project for more than 15 years. For these council members, participating in this water project has meant that they have worked on every stage of the policy process: they have identified a need in the community and collaborated with other stakeholders in planning and carrying out projects. Today, they continue to manage and keep the water project running with little or no help from the municipal authorities. The kind of participation they have achieved has allowed them to take ownership and be in control of the project, which empowers them to make decisions and find solutions on present and foreseen problems (28). As individual community members, these men participate and engage in projects with the council, their respective churches, and with the local school because participation creates the agency they feel is necessary to live a peaceful life where neighbors can trust each other (29).

Conclusion

The case of El Triunfo's community-level council shows that a participatory scheme needs time, continued support, and a constant flow of successful experiences. This provides the kind of stable participatory practices that involves community members in a process of empowered decision-making. When it comes to water projects such as the one presented in this study, communities need active, reflexive leaders who have enough funding and support from key stakeholders (such as the teacher, the municipal government, or donor agencies) in order to be able to design and implement a policy.

The challenge for El Triunfo now is not to maintain its current levels of community participation but to transmit the values that are behind this group of council members to the next generation. Indeed, the issue at hand seems to be how to get younger community members involved and engaged in a process that is similar to, and that builds on, the one this council has achieved.

Access to water is a universal right, and states and municipal governments that are not able to provide can start a process of progressive realization where working with community groups is only the first step to build a system that can provide safe water for the entire population. For this to happen, clear guidelines, institutions, and funding opportunities have to exist at the national and municipal level, so that villages can use the system in their favor.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alison Herna′ndez and Barbara Starfield for their valuable and insightful comments on earlier versions of this draft. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Kleemeier E. The impact of participation on sustainability: an analysis of the Malawi rural piped water scheme program. World Dev. 2000;28:929–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mankutty S. Community participation: lessons from experiences in five water and sanitation projects in India. Dev Policy Rev. 1998;16:373–404. doi: 10.1111/1467-7679.00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TAJ, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372:1661–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Primary health care: now more than ever. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CSDH. Closing the gap in a generation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO/UNICEF. Primary health care: international conference on primary health care; 1978. Sep, pp. 6–12. Alma-Ata. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Follér ML. Social determinants of health and disease: the role of small-scale projects illustrated by the Koster Health Project in Sweden and Ametra in Peru; 1992. pp. 229–39. Cuadernos Saúde Pública. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bambra C, Gibson L, Sowden A, Wrightm K, Whiteheadm M, Petticrew M. Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;2010:264–91. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. The right to water. Human rights fact sheet 35. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. The right to water. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luján Muñoz J. Guatemala: breve historia contemporánea.[Guatemala: brief history of contemporary times]; Mexico DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores W, Ruano AL, Phe Funchal D. La participación social en un contexto de violencia política: implicaciones para la promoción y ejercicio del derecho a la salud en Guatemala.[Socialparticipation within the context of political violence: implications for the promotion and exercise to the right to health in Guatemala]. Health Human Rights; 2009. pp. 37–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CEH. Guatemala memoria del silencio.[Guatemala, memory of silence]. Guatemala; 1999. Comisión para el Esclarecmiento Histórico. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MINUGUA. Los acuerdos de paz.[Peace accords] 2004. http://www.minugua.guate.net/ACUERDOSDEPAZ/ACUERDOSESPA%D1OL/AC%20SOCIOECONOMICO.htm. [cited 17 May 2004] Guatemala: Misión de verificación de las Naciones Unidas en Guatemala.

- 15.Congreso de la República de Guatemala. Ley de consejos del desarrollo urbano y rural.[Rural and urban social development council act]; Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Congreso de la República de Guatemala. Código municipal.[Municipal code]; Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Congreso de la República de Guatemala. Constitución política de la República de Guatemala.[Political constitution]; Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobos CA. Institucionalidad del agua en Guatemala.[Institutionality of water in Guatemala] Guatemala: CONGCOOP; 2003. http://www.congcoop.org.gt/design/content-upload/institucionalidaddelagua.pdf. [cited 20 May 2010] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spillman TR, Webster TC, Alas H, Waite L, Buckalew J. Evaluación de recursos del agua en Guatemala.[Evaluation of Guatemala's water resources] Guatemala: Cuerpo de Ingenieros de los Estados Unidos de América; 2000. http://www.sam.usace.army.mil/en/wra/Guatemala/Guatemala%20WRA%20Spanish.pdf. [cited 10 May 2010] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ENCOVI. Encuesta nacional de condiciones de vida.[Survey of the living conditions of the nation]; Guatemala: Instituto Nacional de Estadística; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.INE. Características de la población y de los locales de habitación censados.[Characteristics of censed the population and of its living conditions]; Guatemala: Instituto Nacional de Estadística; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Municipalidad de Palencia. Datos generales del municipio de Palencia.[General information about the municipality]. Palencia. 2009. www.munipalencia.com/datos.htm. [cited 15 January 2009]

- 23.Riessman CK. Narrative analysis: qualitative research methods series 30. London: SAGE; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. London: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortazzi M. Narrative analysis in ethnography. In: Paul Atkinson AC, Sara D, John , Lyn L, editors. Handbook of Ethnography. London: SAGE; 2008. pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durkheim E. The division of labor in society. New York: The Free Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliot J. Using narrative in social research. London: SAGE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnstein R. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Planning. 1969;35:216–24. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giddens A. Sociología. Mexico DF: Alianza Editorial; 2005. [Google Scholar]