EMBO Rep (2011) advance online publication. doi:; DOI: 10.1038/embor.2011.151

Fasting triggers a complex metabolic programme in the liver to meet the emerging glucose deficit. This includes the immediate harvesting of glucose from glycogen and the activation of genes for gluconeogenesis. After more prolonged fasting, ketogenesis further augments the production of high-energy compounds for the brain and other tissues. At least two transcriptional pathways activate genes for gluconeogenesis. One is anchored by the cyclic-AMP-responsive-element-binding protein (CREB), which is stimulated by its co-activator CRTC2. The other is mediated by the forkhead transcription factor FOXO1, which is co-activated by PGC-1α. The study by Noriega et al published this month shows how the regulation of transcription of the sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) gene underlies the programme of energy homeostasis through these pathways.

…CREB functions positively and ChREBP negatively in SIRT1 transcription

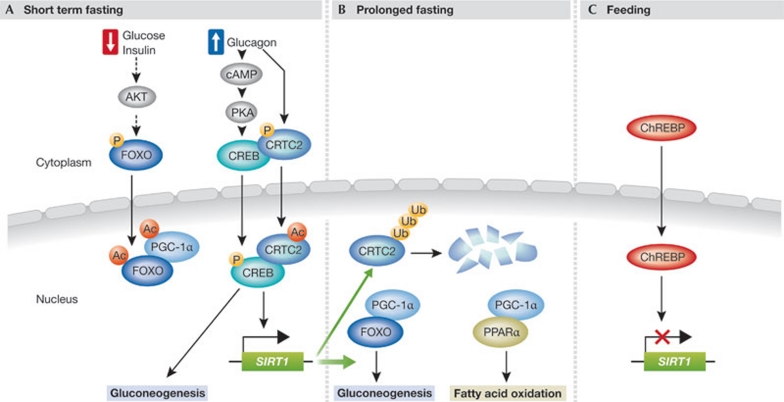

Previous studies suggest a temporal programme for the maintenance of gluconeogenesis after imposition of fasting (Fig 1; Liu et al, 2008). In the first phase, glucagon causes the dephosphorylation of CRTC2 in the cytoplasm and its entry into the nucleus to join forces with CREB. Phosphorylation of CREB itself is triggered concurrently by glucagon activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A. After 12–18 h (in mice), a second phase ensues when the CREB transcriptional pathway has been attenuated by the proteolytic destruction of CRTC2 and the PGC-1α axis becomes dominant.

Figure 1.

Nutrient availabitily regulates SIRT1-mediated metabolic response. (A) Short-term fasting causes a decrease in blood glucose and insulin levels, and a concomitant rise in glucagon. Both of these hormonal changes initiate cellular pathways that induce gluconeogenesis. Low insulin signalling results in the dephosphorylation of the FOXO transcription factor and its translocation to the nucleus. Glucagon leads to an increase in cyclic AMP levels and activation of PKA, which phosphorylates CREB and drives its translocation to the nucleus. Glucagon also leads to the dephosphorylation of the CREB co-activator CRTC2 to trigger its translocation to the nucleus. The transcriptional complex CREB–CRTC2 activates the transcription of gluconeogenic genes and of the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1. (B) In a second phase of fasting, after a more prolonged deprivation of food, increased SIRT1 deacetylates CRTC2 and targets it for ubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome, thereby terminating the transcriptional activity of CREB. SIRT1 also deacetylates PGC-1α, FOXO and PPARα increasing their transcriptional activity. PGC-1α co-activates PPARα to induce the expression of fatty acid oxidation genes, and FOXO to maintain the expression of gluconeogenic genes. (C) In the fed state, SIRT1 expression is repressed by the activity of ChREBP transcription factor, which translocates to the nucleus. CREB, cyclic-AMP-respon¬sive-element-binding protein; CRTC2, CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2; FOXO1, Forkhead box protein O1; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1α; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; ChREBP, carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein; SREBP1, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1; PPARα, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α. PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase A.

The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 has been shown to play a key role in mediating the switch from phase 1 to phase 2. To wit, SIRT1 deacetylates CRTC2, exposing a critical lysine for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the protein (Liu et al, 2008). SIRT1 also has been shown to deacetylate and activate both FOXO1 and PGC-1α (Brunet et al, 2004; Rodgers et al, 2005), thereby potentiating the maintenance of phase 2 levels of gluconeogenesis after the loss of CRTC2.

The lingering question has been: what governs the regulation of liver SIRT1 itself during fasting? Now Noriega et al show that SIRT1 transcription is regulated by a short promoter sequence that contains overlapping and competing sites for two transcription factors, the aforementioned CREB, and ChREBP, a factor that is known to be activated by feeding to mediate energy dispersal and storage (Uyeda & Repa, 2006). CREB functions positively and ChREBP negatively in SIRT1 transcription (Noriega et al, 2011). Thus, after imposition of fasting, CREB would activate not only genes for gluconeogenesis, but also the SIRT1 gene with a peak 18 h after fasting. One reason the concomitant activation of SIRT1 transcription and gluconeogenesis is well timed is because gluconeogenesis converts NADH into NAD+, and higher NAD+ levels in the nuclear–cytoplasmic pool ought to favour high SIRT1 deacetylase activity.

…after imposition of fasting, CREB would activate not only genes for gluconeogenesis, but also the SIRT1 gene…

Moreover, by activating SIRT1 transcription, CREB would programme destruction of its own transcriptional network through deacetylation of CRTC2, as described above. SIRT1 might thereby limit the duration of the first phase of gluconeogenesis and, by co-activating PGC-1α, promote the onset of the second. In addition, the known deacetylation and repression of SREBP1 by SIRT1 (Ponugoti et al, 2010; Walker et al, 2010) would help shut down fat and cholesterol synthesis at this time. SIRT1 transcription was shown to return to normal after 24 h of fasting, probably as a result of the destruction of CRTC2. It appears that normal levels of SIRT1 suffice for maintenance of gluconeogenesis during prolonged fasting.

In a second finding, Noriega et al show a connection between regulation of SIRT1 transcription and the cessation of fasting. It is important for animals to turn off gluconeogenesis promptly after re-feeding, and the action of insulin is critical in this regard by triggering phosphorylation of FOXO1 by AKT to relegate forkhead to the cytoplasm. Noriega et al show that ChREBP downregulates SIRT1 transcription after re-feeding by binding to a site in the SIRT1 promoter, which overlaps the CREB site. Thus, the PGC-1α axis is shut off, as is CREB in the setting of high insulin and low glucagon. This mechanism of ChREBP repression of SIRT1 transcription thus reinforces the repression of transcription of genes for gluconeogenesis initiated by the movement of FOXO1 to the cytoplasm.

…ChREBP downregulates SIRT1 transcription after re-feeding by binding to a site in the SIRT1 promoter, which overlaps the CREB site

The above regulation of expression of gluconeogenesis genes during dietary changes might be integrated into a broader context of physiological changes triggered by fasting. Enzymes for gluconeogenesis are generally distinct from the enzymes catalysing the reverse reaction in glycolysis. However, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase is an exception and catalyses both the forward and reverse reaction. It is intriguing that this enzyme is acetylated to promote the forward reaction in glycolysis, and its deacetylation by the sirtuin CobB triggers its gluconeogenesis activity (Wang et al, 2010). Thus, SIRT1 not only mediates regulation of the genes for central metabolism as a function of diet, but can also directly control their enzymatic activity.

…the regulation of SIRT1 gene expression by CREB and ChREBP helps to control an orchestrated programme of cellular physiology in response to dietary needs

Finally, it is noteworthy that PGC-1α activates not only gluconeogenesis but also mitochondrial biogenesis, while another SIRT1 substrate PPAR-α activates oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria (Purushotham et al, 2009). The upregulation of SIRT1 in the initial phase of fasting by CREB would therefore also programme cells for oxidative metabolism, including the use of fatty acids, amino acids and acetate as energy sources to fuel gluconeogenesis. In addition, expression of another sirtuin, SIRT3, is also upregulated by fasting (Hirschey et al, 2010). This mitochondrial sirtuin deacetylates enzymes for oxidative metabolism, as well as enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen species (Bell & Guarente, 2011). In summary, the regulation of SIRT1 gene expression by CREB and ChREBP helps to control an orchestrated programme of cellular physiology in response to dietary needs.

Acknowledgments

Studies in the Guarente lab are supported by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bell EL, Guarente L (2011) Mol Cell 42: 561–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet A et al. (2004) Science 303: 2011–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschey MD et al. (2010) Nature 464: 121–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y et al. (2008) Nature 456: 269–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noriega LG et al. (2011) EMBO Rep [Epub 12 August 2011] doi:; DOI: 10.1038/embor.2011.151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponugoti B et al. (2010) J Biol Chem 285: 33959–33970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushotham A et al. (2009) Cell Metab 9: 327–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JT et al. (2005) Nature 434: 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda K, Repa JJ (2006) Cell Metab 4: 107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AK et al. (2010) Genes Dev 24: 1403–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q et al. (2010) Science 327: 1004–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]