SYNOPSIS

Research on coparenting has grown over the past decade, supporting a view of coparenting as a central element of family life that influences parental adjustment, parenting, and child outcomes. This article introduces a multi-domain conception of coparenting that organizes existing research and paves the way for future research and intervention. This article advances a conceptualization of how coparenting domains influence parental adjustment, parenting, and child adjustment. An ecological model that outlines influences on coparenting relationships, as well as mediating and moderating pathways, is described. Areas of future research in the developmental course of coparenting relationships are noted.

INTRODUCTION

It has been clear for some time that the marital or couple relationship is closely associated with parenting and child adjustment. Twenty years ago, respected scientists concluded from a growing literature-base that the best familial predictor of child behavior problems is marital discord (Emery, 1982; Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1982). Around the same period, Belsky prodded researchers to integrate family sociologists’ concerns with the effects of a new baby on marriage with developmental psychologists’ interest in parenting and the parent-infant relationship (Belsky, 1981). Since then, researchers have made significant progress identifying the aspects of interparental relationships most salient for parenting and child adjustment. However, despite progress in basic research, the applied literatures on marital and parenting interventions have remained largely independent (Sanders, Nicholson, & Floyd, 1997). In other words, intervention has continued to focus on either the couple relationship or on parenting and child outcomes. One obstacle to a greater integration of intervention approaches may lie with a lack of conceptualization bridging the two domains.

The most important practical point of this article is that recent advances in family research on “coparenting” have created the basis for bridging the marital and parenting intervention divide. However, before applied- and experimentally-minded scientists can translate the findings on coparenting into effective interventions, a comprehensive framework for understanding the coparenting relationship and its links with parenting and child adjustment is required. Providing an outline of such a conceptualization, even if tentative and ultimately wrong, in some places, is the burden of this article. This article does not intend to address with finality all important questions about coparenting and how to study them. Rather, this article intends to integrate and synthesize disparate findings through coherent conceptual models and thus allow (and prod) both basic and applied family researchers to be more strategic in the questions they pose regarding the interface of parent – child and parent – parent relationships.

An explicit notion of coparenting emerged from two sources: Family systems theorists described how the executive subsystem, comprised of parents in their role as co-managers of family members’ behaviors and relationships, regulates family interactions and outcomes (Framo, 1972;P. Minuchin, 1985; S. Minuchin, 1974). Object relational theorists Weissman and Cohen (1985, p. 25) portrayed how the coparenting relationship or alliance, through the acknowledgment and respect each parent demonstrates for the other’s parenting, may help support parents’ self-esteem “when stressed by the seemingly endless frustrations and tension that occur in the many contingencies of parenthood.” In the following section, I integrate these concerns by proposing that the coparenting relationship affects parenting and child adjustment partly through its effect on parental adjustment (see also J. McHale, Lauretti, Talbot, & Pouquette, 2002).

Defining Coparenting and Identifying Coparents

In this article and the research literature generally, “coparenting” is a conceptual term that refers to the ways that parents and/or parental figures relate to each other in the role of parent. Coparenting occurs when individuals have overlapping or shared responsibility for rearing particular children, and consists of the support and coordination (or lack of it) that parental figures exhibit in childrearing. The coparenting relationship does not include the romantic, sexual, companionate, emotional, financial, and legal aspects of the adults’ relationship that do not relate to childrearing. Furthermore, the term coparenting does not imply that parenting roles are or should be equal in authority or responsibility. The degree of equality in the coparenting relationship is determined in each case by the participants, who are influenced of course by the larger social and cultural context.

A focus on the importance of coparenting need not lead to a reification of the concept: The coparenting relationship does not exist outside of, apart from, or independently of the overall relationship between parents. In fact, coparenting is integrally linked to other aspects of the coparents’ overall relationship, as has been shown by several researchers (Maccoby, Depner, & Mnookin, 1990; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, et al., 2000; see the following section on the “Ecological Model”). Nonetheless, the usefulness of the concept of coparenting lies in the conceptual distinction created between dimensions that relate to the parental role versus other intimate, conflictual, instrumental, and role-related aspects of parents’ relationships.

Before completing their rich observational investigation of coparenting in new families’ homes, Gable, Belsky, and Crnic (1992, p. 291) wrote that they suspected that for some couples, the newly developing coparenting relationship “will be a place where latent relational strengths emerge and serve to solidify the marriage. For others, it may prove to be a battleground, where self-interests compete.” Gable et al.’s developmental view of coparenting as a new and somewhat independent influence on family relationships has been upheld by scholars who have pointed out that not all parents who have a distressed relationship with each other display negative coparenting behaviors; and not all parents who display negative coparenting behaviors are dissatisfied with their overall relationship (Cowan & McHale, 1996; Van Egeren, 2000). Thus, coparental distress is not synonymous with relationship distress, nor is supportive coparenting synonymous with relationship intimacy (Feinberg, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2003; Frank, Jacobson, & Hole, 1986; Gable, Belsky, & Crnic, 1995; McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, et al., 2000; Russell & Russell, 1994).

Much, although not all, of the research on coparenting to date has been conducted with somewhat limited samples comprised of white, North American, middle-class families. Only recently have researchers begun to examine coparenting among diverse family types, cultures, contexts, and stages (Hortacsu, 1999; McHale, Rao, & Krasnow, 2000). The limited sample representativeness of the available research inevitably affects the framework proposed here in at least four ways that future research will hopefully address more fully. First, parenting cannot be defined simply on the basis of biology, gender, marital, or legal status. Parenting, and hence coparenting, is instead a function that involves meeting children’s needs for physical and emotional sustenance, protection, and development (see Bornstein, 2002; McHale et al., 2002). Important coparents (e.g., adoptive, step-parents, or gay - lesbian parents, a mother and her boyfriend, grand- mother, or other actual or Active kin) for many children may be missed if one is looking only for the biological, cohabiting, and married “mothers” and “fathers” in the narrowly defined “traditional” nuclear family.1

Second, the form of the coparenting relationship is shaped to a large extent by parents’ beliefs, values, desires, and expectations, which in turn are shaped by the dominant culture as well as subcultural themes within socioeconomic, ethnic, religious, and racial groups. For example, subcultural norms influence the way that individuals and families view gender as organizing family relationships. (I do not consider in sufficient detail issues regarding coparenting in diverse family systems here because of space; the interested reader is referred to McHale et al., 2002.)

Third, a family’s social context and material resources influence the extent to which individual parents and families can manifest those beliefs in practice (McHale et al., 2002). For example, although coparents may subscribe to gender-neutral beliefs, economic context and institutional pressures may result in one parent being in a better position to maximize the family’s income as a worker outside the home. Finally, families are not static, but are relentlessly changing due in part to developmental processes occurring within all individuals. Thus, in additional to individual and between-family differences, coparenting arrangements change over time (e.g., Kreppner, 1988).

This Article

Despite some limitations in the available research base on coparenting, there are consistent findings on which models can be built to inform further research and intervention. The most consistent and general finding is that coparenting is linked both cross-sectionally and longitudinally to parental adjustment parenting, and child adjustment (henceforth collectively referred to in abbreviated form as “relevant” or “family outcomes”). For example, measured in different ways in different studies, negative aspects of coparenting relations have been consistently linked to child and adolescent emotional and behavioral problems (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996; Deal, Halverson, & Wampler, 1989; Floyd & Zmich, 1991; Jouriles, Murphy, Farris, Smith, & et al., 1991; Margolin et al., 2001; McHale, 1995; Vaughn, Block, & Block, 1988). Furthermore, as described in the following section,, the co-parenting relationship is more closely linked to parenting and child adjustment than are other aspects of the interparental relationship.

There are two important implications of these findings that serve to organize this article. First, the distinction between coparenting and other aspects of interparental relationships yields enhanced precision in the specification and identification of risk processes influencing parenting and child adjustment (Margolin et al., 2001). From this perspective, the importance of coparenting for parenting and child adjustment is a result of “domain specificity” — that is, coparenting relationships are more proximal and thus more tightly linked to child adjustment than are other aspects of interparental relationships. However, it is not enough to be satisfied by pointing to “coparenting” in general; rather, it is important to describe what coparenting is in more detail: What are the components of the coparenting relationship, and how do they relate to parenting and child adjustment. I take a step in this direction by presenting a multi-component model of the structure of the coparental relationship. I also propose processes through which each component influences the outcomes of parental adjustment the overall interparental relationship, parenting, and ultimately child adjustment.

Second, the links between coparenting and family outcomes support the claim that the coparenting relationship is, at least to some extent, “the center about which family process evolves” (Weissman & Cohen, 1985, p. 24). If coparenting is centrally involved in causal risk processes, then the coparenting relationship may be an important conduit through which individual, family, and external stresses disrupt health-promoting parenting and child adjustment. As such, the coparenting relationship may be an important mediator and moderator of the influence of extrafamilial stresses and supports on family members and relationships. Thus, after describing a model of the internal structure of coparenting, this article proposes an ecological model in which coparenting plays a central role.

DOMAIN SPECIFICITY AND A MODEL OF COPARENTING

Margolin et al. (2001) proposed that difficult or negative coparenting relationships may represent causal risk mechanisms that link the quality of the interparental relationship with family outcomes, although difficulty in the overall interparental relationship may merely be a marker or indicator of risk (Rutter, 1994). Precisely specifying the mechanisms that underlie the association of interparental relationships and child adjustment is crucial for developing successful preventive interventions for families. In the absence of experimental data that such preventive interventions would produce, we can examine Margolin’s theory by assessing whether there is evidence for domain specificity in correlational data. In other words, are measures of components of coparenting more closely related to parenting and child adjustment than are measures of the overall interparental relationship?

The first test of this relation was conducted with divorced families (Camara & Resnick, 1989). Divorce researchers were among the first to investigate coparenting (e.g., Ahrons, 1981; Forehand et al., 1986) because research suggested that it was not the divorce per se, nor even particular custody arrangements, but rather a handful of postdivorce factors such as parental absence, economic disadvantage, and most importantly ongoing interparental conflict that negatively affected children’s adjustment (Amato & Keith, 1991a; Kline, Tschann, Johnston, & Wallerstein, 1989; Maccoby et al., 1990; Whiteside & Becker, 2000). Camara and Resnick’s (1989) study of divorced families found that the degree of cooperation versus noncooperation in the parental role, but not conflict in the spousal role, was predictive of parental warmth and commitment, as well as children’s self-esteem and play behavior.

Camara and Resnick’s (1989) finding has been supported by several studies over the last decade with nondivorced, two-parent families: Coparent relations are a stronger influence on parenting and child adjustment than are other aspects of the couple relationship (Abidin & Brunner, 1995; Bearss & Eyberg, 1998; Feinberg et al., 2003; Jouriles, Murphy, et al., 1991; Snyder, Klein, Gdowski, & Faulstich, 1988). For example, a longitudinal investigation found that observed interparental conflict during family play with a 6-month old infant, but not dyadic marital interaction conflict, predicted attachment security at 3 years (Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 2000).

These correlational findings support (but do not prove) Margolin’s domain-specific view that coparenting relations are more proximally and causally linked to parenting and child outcomes than are other aspects of interparental relationships. This is, of course, not completely novel. Grych and Fincham (1990) pointed out that the effect of interparental conflict on children is greater when the conflict centers on child-related issues. However, the research on coparenting over the last decade now allows for an extended view of potential causal risk processes beyond child-related marital conflict; the literature suggests that the causal risk processes in the parental relationship include all the ways that parents do or do not coordinate with and support each other in their roles as parents. This broadening of the arena of interest, from certain aspects of marital conflict to the many ways parents relate in the context of childrearing, now requires an organizing conceptual model to integrate the material and help researchers and interventionists make sense of the expanding field of coparenting relations.

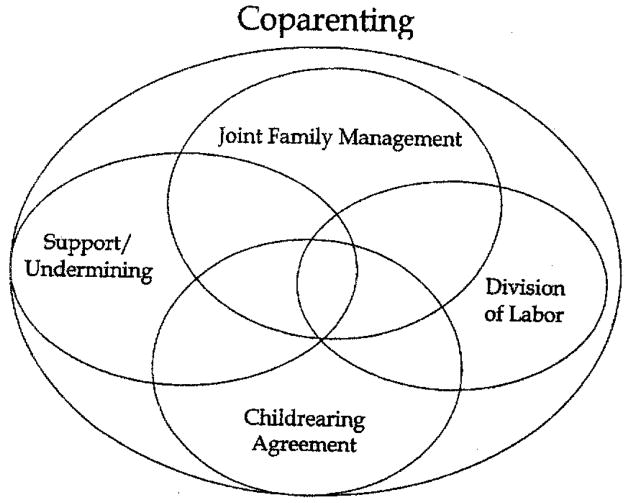

The model of the coparenting relationship presented here is drawn from several sources (e.g., Belsky et al., 1996; Brody, Flor, & Neubaum, 1998a; Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Ihinger-Tallman, Pasley, & Beuhler, 1995; Margolin et al., 2001; McHale, 1995) and portrays coparenting as comprised of four related components. These four components are agreement or disagreement on childrearing issues, division of (child-related) labor, support – undermining for the coparental role, and the joint management of family interactions.

In the absence of empirical information on the interrelations of these four components, I assume that the components are both moderately associated and also partly distinct. There is likely considerable variability across families in the degree of linkage across components. For example, some parents who disagree on childrearing values may yet find ways to offer each other coparental support, effectively negotiate responsibilities in a satisfactory manner, and/or contain conflict so that children are not exposed to undue hostility. Other parents who disagree on childrearing values may demonstrate more detrimental patterns of coparenting in other spheres (see McBride & Kane, 1998). Given these considerations, the model of coparenting relations is portrayed in Figure 1 as four overlapping com- ponents. Even if the overlap among two or more components is great, maintaining the conceptual distinctions may be useful. For example, one measure of an effective coparenting intervention may be whether correlations between childrearing disagreement and coparental support are attenuated. In other words, an effective intervention might not necessarily decrease the level of disagreement on childrearing issues, but it might help parents manage these disagreements in ways that allow parents to maintain high levels of mutual support.

FIGURE 1.

Model of Coparenting Components

Childrearing Agreement

The first component of coparenting is the degree to which parental figures agree on a range of child-related topics, including moral values, behavioral expectations and discipline, children’s emotional needs, educational standards and priorities, safety, and peer associations. Given that parents’ attitudes are based partly on their own families of origin, it is not surprising that coming to an agreement on childrearing issues is an area of frequent difficulty, according to parents of infants themselves (Feinberg, 2002). This component has generally been viewed as a single dimension, with agreement and disagreement forming opposite ends of a bipolar scale.

Childrearing disagreement is linked to child behavior problems in the preschool and kindergarten period (Block, Block, & Morrison, 1981; Deal et al., 1989), during adolescence (Feinberg et al., 2003), as well as longitudinally across these periods (Vaughn, Block, & Block, 1988). In addition to child behavior problems, childrearing disagreement has also been shown to be linked with boys’ moral reasoning, sociability, and alienation, and girls’ self-confidence, responsibility, social skills, ability to cope with adversity, and free expression (Vaughn, Block, & Block, 1988).

Childrearing disagreement per se may not lead to negative family outcomes. For example, some parents who successfully “agree to disagree” may be able to maintain high levels of mutual coparenting support, actively and respectfully negotiate disagreements, and adopt compromises on which to base family management. Childrearing disagreement may have negative effects on the relevant family outcomes when acute or chronic disagreement disrupts parenting or other domains of coparenting. For example, acute or chronic disagreement may lead to difficulty forming coordinated childrearing strategies, mutual undermining and criticism, and/or hostile interparental conflict (Belsky, Crnic, & Gable, 1995; Grych & Fincham, 1993; Jouriles, Murphy, et al., 1991; Mahoney, Jouriles, & Scavone, 1997; Van Egeren, in press).

Division of Labor

The second component of coparenting relates to the division of duties, tasks, and responsibilities pertaining to daily routines involved in childcare and household tasks, and to ongoing responsibilities for child-related financial, legal, and medical issues. Most of the research in this area has focused on two-parent, mother – father families. Mothers report that the issue of household chores is the single most important trigger of conflict in the postpartum period (Cowan & Cowan, 1988). Mothers’ perceptions in this domain appear to be crucial, probably because mothers generally perform the majority of household tasks and take on ultimate responsibility for almost all child-related issues (Aldous, Mulligan, & Bjarnason, 1998; Demo, Acock, & Hurlbert, 1993; Hetherington et al., 1999; Lamb, 1995).

Mothers’ perception of fairness in fathers’ contributions is linked to increased marital quality over the transition to parenthood, whereas perception of inequity is linked to decreased marital quality (Terry, McHugh, & Noller, 1991). However, mothers’ or fathers’ perceptions of how child-rearing labor is divided, by themselves are not predictive of parental or couple adjustment (Belsky & Hsieh, 1998; Bristol, Gallagher, & Schopler, 1988). The issue in this domain is satisfaction; Are the parents satisfied with both the process of negotiating responsibilities and the division that results? Satisfaction is a result of how the division of labor comports with parents’ expectations and beliefs regarding contributions to childrearing (C. P. Cowan, 1988; Hackel & Ruble, 1992; MacDermid, Juston, & McHale, 1990), The discrepancy between each parent’s expectations and perceptions of responsibility for childcare support are significantly related both to depression and marital adjustment for both parents (also see Kalmuss, 1992; Voydanoff & Donnelly, 1999). When expectations are not met, a sense of unfairness and resentment may be engendered (Goodnow, 1998), leading to increased parental stress that may interfere with warm, sensitive interaction with the child.

A potentially important aspect of how parents manage the division of labor is the degree of flexibility versus rigidity parents lend to these arrangements. Some couples, for example, may instantiate fairly firm rules about who is to do what. Other couples may approach tasks in a flexible manner, adjusting arrangements as situations arise. In a general sense, a balance of structure and flexible adaptability in family functioning may be optimal (Barnes & Olson, 1985). However, during a period of stress such as the transition to parenthood or a child’s transition to school, increased flexibility may provide opportunities for meeting needs that a more structured approach does not (see Guelzow, Bird, & Koball, 1991). In addition, as new tasks and roles are being explored, a rigid arrangement may prematurely foreclose possible solutions. However, for some parents who have difficulty negotiating situations and engage each other with reflexive hostility, an increased level of structure in coparenting arrangements may eliminate some opportunities for conflict.

Support – Undermining

This component of coparenting relates to each parent’s supportiveness of the other: affirmation of the other’s competency as a parent, acknowledging and respecting the other’s contributions, and upholding the other’s parenting decisions and authority (Belsky, Woodworth, & Crnic, 1996; McHale, 1995; Weissman & Cohen, 1985). The negative counterpart of coparental support is expressed through undermining the other parent through criticism, disparagement, and blame. Some parents adopt a competitive approach in which a gain for one in authority or warmth with the child is a loss for the other (Ihinger-Tallman et al., 1995).

The degree of support versus undermining has been linked with parent and child adjustment, such as perceived parental competence and child and adolescent behavior problems (Floyd & Zmich, 1991); authoritative parenting and lower parenting stress (Abidin & Brunner, 1995); and, independent of variance accounted for by observational ratings of parents’ child behavior management, preschool boys’ inhibition (Belsky, Putnam, & Crnic, 1996).

It is not completely clear whether the degree of support versus undermining should be conceptualized and measured as opposite poles on a single continuum, or as two independent, although correlated, constructs. Margolin, for example, has found factor analytic evidence based on parent report of coparenting relations that factors labeled “cooperation” and “conflict” form separate dimensions (Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001). McHale (1995) has pursued a similar strategy, differentiating harmonious coparenting from hostile – competitive coparenting.

Support in the coparenting relationship can be seen as a particular form of social support. General social support is an important positive influence on maternal adjustment (Brown & Harris, 1978; Crnic & Greenberg, 1987). However, when parents are married, spousal support seems to be an especially important source of social support (Quinton, Rutter, & Liddle, 1985) and is associated with maternal adjustment, parenting competence, and marital outcomes (Dunn, 1988; Pasch & Bradbury, 1998). A low level of partner support is related to severity of maternal postpartum depression (O’Hara & Swain, 1996) and social emotional problems in the children of adolescent mothers (Sommer et al., 2000). Furthermore, other sources of support are unable to compensate for the inadequacy of marital or intimate partner support (see Cutrona, 1996a, 1996b; also see Crnic & Greenberg, 1987; Wandersman, Wandersman, & Kahn, 1980).

Although much of the research in this area has focused on the effects of social support for mothers, similar evidence has been collected indicating that mothers’ support of fathers’ parenting is a key factor influencing paternal adjustment and parenting (Allen & Hawkins, 1999; Grossman, Eichler, & Winickoff, 1980; Jordan, 1995; Seltzer & Brandreth, 1995). In addition, where a single mother resides with her own mother — that is, the child’s grandmother—harmonious and supportive relationships between the mother and grandmother are linked to maternal adjustment and positive parenting (Brody & Flor, 1996; Kalil, Spencer, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 1998). Kalil’s study of young single mothers reported no main effect of mother – grandmother coresidence on maternal adjustment; rather, the affective quality of the mother – grandmother relationship was a significant predictor of maternal depression (Kalil et al., 1998). Coresidence did interact with affective relationships, such that the most depressed mothers were those who lived with and had a negative relationship with the grandmother. This finding supports the view that the structural features of a coparenting relationship (i.e., whether coparents are mothers and fathers or mothers and grandparents, whether the coparents live together or not) are relatively unimportant when considered independent of the family’s functional, process, and affective relations (McHale et al., 2002).

The mechanisms through which social support exerts a generally beneficial influence are not frequently addressed in the literature.2 However Cutrona and Troutman (1986) reported that social support exerts a protective function against maternal depression primarily through the mediating role of parental self-efficacy. The concept of parental self-efficacy is based on Bandura’s theory regarding the importance of the self-perception that one possesses the internal ability to manage difficult external conditions (Bandura, 1977,1989). In the stress-coping framework, self-efficacy corresponds to a “secondary appraisal” (Lerman & Glanz, 1997) or assessment of one’s ability to manage either a stressor or one’s reaction to a stressor. Teti has proposed that parental efficacy is the “final common pathway” to disruptions in care-giver sensitivity (Teti, O’Connell, & Reiner, 1996). Given the key role of parental self-efficacy in mediating the effects of social support on maternal depression and mediating disruptions in parental sensitivity, parental self-efficacy may be a crucial link between coparenting and parenting performance. This view echoes (and sharpens) Weissman and Cohen’s (1985) account of coparenting as a support for parental self-esteem.

Self-efficacy theory and research (Donovan, 1981) suggest a cycle in which episodes of parenting success (e.g., getting a newborn to “latch on” and nurse; soothing a tantrumming toddler; evoking polite table manners from a 7-year-old; facilitating self-disclosure from a distraught teenager) leads to increased parental self-efficacy. These perceptions of efficacy yield confidence and promote further competent-sensitive, active, persistent, non-distressed, problem-solving oriented-parenting (Shumow & Lomax, 2002). Parental efficacy increases to the extent that success is viewed as a result of the internal ability to manage difficult external conditions (Bandura, 1989). It is in the interpretation of these factors that significant others in the social environment, especially the coparent, influence a parent’s sense of efficacy (Tice, 1992). The coparent may contribute to the parent’s understanding of their internal ability, how difficult the external conditions are, and even what should be considered in some sense an external condition that one may have little control over (e.g. postpartum blues). As a result, coparenting support serves to bolster a parent’s sense of performing the new parenting role adequately and competently, leading to greater confidence in the ability to handle difficult situations (Frank et al, 1986) and thus to more competent parenting and ultimately enhanced child adjustment.

Although self-efficacy may prove to be an important construct through which the influence of the coparenting relationship is mediated, it is likely not the only such mediator. For example, whereas self-efficacy is primarily a cognitive construct, emotion processes may also be important. Thus, coparental undermining may lead a parent to feel overwhelmed or even flooded by negative emotion. Cognitive and emotional processes are likely intertwined here in that the feeling of being overwhelmed suggests a low level of self-efficacy; however, the cognitive and emotional elements may be differentially important across individuals. Thus, the investigation of emotion processes and the regulation of emotion may also contribute to understanding the effects of coparental support and undermining.3

Joint Family Management

The management of family interactions is an important executive subsystem responsibility of parents, and can be seen as extending in at least three broad directions. First, parents are responsible for controlling their behaviors and communication with each other. Some interparental behaviors, most notably violent hostility toward each other, affect their parenting and their children. Second, parents’ behaviors and attitudes set boundaries on aspects of their relationships, and thus either engage or exclude other family members in the parent-parent relationship. For example, in the context of hostile interparental conflict, parents may use children to attack each other and thus leave children feeling caught in the middle. Third, even in the absence of overt conflict or other problematic interactions, parents vary in the degree to which they contribute in a balanced manner to whole-family interactions. That is, parents can strike a balance in terms of their involvement in triadic or larger interactions, or one can take the lead and the other can withdraw. I explore each of these three aspects of family management separately. There are undoubtedly other aspects of family management that relate to coparenting, but these are selected as they have received significant attention from researchers.

Interparental conflict

Exposure of children to interparental conflict—especially frequent, unresolved, and/or physical conflict (Grych & Fincham, 1990)—is associated with parenting quality and child adjustment, particularly children’s externalizing disorders (Buehler et al., 1998; Emery, 1982; Johnson & O’Leary, 1987; Jouriles, Bourg, & Farris, 1991; Rutter, 1994), but also internalizing disorders and other problems (Holden & Ritchie, 1991; Jouriles, Barling, & O’Leary, 1987; Jouriles, Murphy, & O’Leary, 1989). There is some evidence to suggest that high levels of unregulated interparental conflict act as a disinhibitor to children (Cummings, Davies, & Simpson, 1994). For example, Owen and Cox (1997) report that prenatal and 3-month postpartum interparental conflict is linked to disorganized infant attachment patterns at 1 year, independently of both parental ego development and warm, sensitive parenting. It may be that hostile interparental conflict provokes acute emotional responses such as anxiety in young children, undermining childrens’ ability to respond appropriately to less extreme environmental cues. It may also be that parents involved in hostile conflict are unable to provide sufficient regulatory soothing and calming, thus depriving children of the opportunity to experience and then learn how to manage their own emotions. Given available evidence on physiological reactions to stress, it seems reasonable to speculate that the effects of marital conflict on children’s self-regulatory mechanisms are partly mediated by long-term physiological changes (El-Sheikh, Cummings, & Goetsch, 1989; Gerra et al., 1993; Gerra et al., 1998; Gottman & Katz, 1989; Nelson & Carver, 1998; Nelson & Bosquet, 2000).

The view proposed here is that exposure of children to hostile interparental conflict represents a coparenting process in that there is a break- down in parents’ joint responsibility to provide for children’s physical and emotional security. Consequently, exposure of the child to acute or chronic conflict is an indicator that (1) the coparents are unable to arrive at a working relationship that allows them to provide security for the child and (2) the existence of this security-providing team may be threatened. The ability of parents to demonstrate resolution of conflict to children may counter both indications of threat, and this may explain why resolution (even if not witnessed first-hand) returns children’s physiological arousal to near-normal levels after observing adult conflict (Cummings et al., 1989; Cummings et al., 1991; Cummings, Simpson, & Wilson, 1993).

The mechanisms linking couple conflict with child adjustment are probably multiple and complex (Frosch et al., 2000; Zimet & Jacob, 2001). For example, the experience of observing parents in conflict may affect children’s sense of security; couple conflict may disrupt parents’ ability to attend to and warmly parent the child; parents may discharge negative emotions toward each other through being harsh with a child (also known as emotional spillover), which may lead to scapegoating a child; or children may adopt the conflict behaviors they witness their parents enacting (Christensen & Margolin, 1988; Cummings, Ballard & El-Sheikh, 1991; Davies, Myers, & Cummings, 1996; Emery, 1982; Fincham, Grych, & Osborne, 1994; Harrist & Ainslie, 1998; Kitzmann, 2000; Owen & Cox, 1997; Tolan & Gorman-Smith, 1997; Vandewater & Lansford, 1998).

Given this extensive body of research on interparental conflict, it would seem that parents should avoid exposing children to conflict. However, a distinction should be made between strategic avoidance of hostile conflict (e.g., avoiding a discussion of a highly conflictual topic until a time when the child is not present) and withdrawal from interaction generally. General withdrawal, which may represent an advanced state of relationship deterioration, has been associated with negative outcomes for children and the couple relationship (Cox, Paley, Payne, & Burchinal, 1999; Katz & Gottman, 1993). Furthermore, not all conflict is harmful to children. For example, constructive management of conflict seems to be beneficial or at least not detrimental to children (Cummings & Wilson, 1999; Easterbrooks, Cummings, & Emde, 1994).

Coalitions

In addition to limiting the exposure of children to hostile conflict, coparents are also responsible for preventing underlying tension from pulling children into the middle of interparental conflict, leading children to take sides or become overly involved in executive decision making. This second domain relates to the triangulation of the child in an overt or covert parent – child coalition (Ihinger-Tallman et al., 1995; McHale, 1997; Minuchin 1985). The focus here is on the issue of generational boundaries and maintenance of an executive subsystem in the family. Triangulation occurs when intergenerational boundaries are blurred, and children become allies or pawns in interparental conflict. For example, parents may make negative comments about the other parent to the child, enlist the child’s aid in verbally attacking the other parent, or force the child to choose an allegiance with one side or the other.

Although most research in this area has not clarified the direction of effects, it is likely that conflict between coparents leads to triangulation, which then has negative effects on the child. The available evidence supports this view: Triangulation of children is correlated with marital dissatisfaction for both parents of preschoolers and preadolescents (Margolin et al., 2001). Even mildly dissatisfied couples tend to triangulate children (Lindahl, Clements, & Markman, 1998). In addition, several family researchers have described the negative effects of triangulation and scape-goating processes within families (Christensen & Margolin, 1988; Jacobvitz & Bush, 1996; Kerig, 1995; Lindahl et al., 1998; Maccoby, Buchanan, Mnookin, & Dornbusch, 1993; Minuchin et al., 1978; Vuchinich, Emery, & Cassidy, 1988).

Parent –child coalitions and triangulation have received the most attention, but it is also possible that conflictual couple relationships may absorb parents’ attention leading to an internally hostile parental “coalition” with weak links to children (Belsky, 1979; Brody & Flor, 1996; McHale, Kuersten, & Lauretti, 1996). In such parent-centered configurations, parents’ sensitivity to children’s needs is obscured by their focus on their own conflict.

Balance

The final aspect of family management is balance between parents in interactions with the child. Fathers and mothers typically have different emphases in interacting with babies (fathers being more physical and arousing, for example; see Palm & Palkovitz, 1988; Lamb, 1995), but the issue of interactional balance concerns in part the relative proportion of time each parent engages with the child in triadic situations (that is, when all three participants are together). Estimates of relative parental involvement with the child garnered from dyadic parent – child interactions are uncorrelated with the interactional balance in triadic interactions (McHale, Kuersten, & Lauretti, 2000). The lack of continuity across contexts may be related to systemic shifts in interactional processes across contexts: Mothers appear to be more engaged and secure, whereas fathers appear less engaged in triadic compared to dyadic parent – child interactions (Gjerde, 1986; Stoneman & Brody, 1981).

Parents’ balance of involvement with the baby in triadic interaction is stable over the first year (Fivaz-Depeursinge, Frascarolo, & Corboz-Warnery, 1996). Furthermore, discrepant levels of parental involvement in triadic play predict later teacher rated anxiety, and interparental hostility and competitiveness in such interactions predict more aggression (McHale & Rasmussen, 1998). Based on research (Gilbert, Christensen, & Margolin, 1984) and theory, one would expect that unbalanced triadic interactions may be especially common for distressed couples: Men experiencing marital distress often withdraw from family life (Amato, 1986; Belsky, Rovine, & Fish, 1989; Christensen & Heavey, 1990; Gottman & Levenson, 1988), whereas some have argued that mothers may compensate for marital distress by becoming increasingly involved with children (Brody, Pellegrini, & Sigel, 1986; see also Biller, 1995; Dunn, 1988; but see Erel & Burman, 1995). However, McHale (1995) found that parenting discrepancy (triadic balance) was not significantly associated with husband or wife reports of marital quality.

Measuring engagement and interaction in triadic situations may be complicated. For example, a strict measurement of amount of time each parent is engaged with the child may fail to account for the efforts of one parent to facilitate the involvement of the other parent in interaction with a child. Thus, what in some circumstances may be a parent’s positive coparenting efforts, encouraging the development of security and intimacy between the other parent and the child by taking more of a back seat-may be registered on the clock as an unbalanced triadic interaction.

Summary

This discussion of the components of coparenting leads to recognition of the complexities involved in trying to conceptualize and compartmentalize aspects of intricate, multiple-determined relationships. As noted previously, the empirical work has not been done yet to determine whether the components of coparenting overlap sufficiently to justify reference to a general coparenting relationship construct. It may be that for some purposes, such an aggregate concept is valid, whereas for other purposes, it is more useful to retain the focus on the individual components. As we examine family process from a wide- angle perspective in which family process is one part of a network of interacting social systems, it may be that the distinctions among the components of coparenting blur to some extent.

COPARENTING AT THE CENTER: AN ECOLOGICAL MODEL

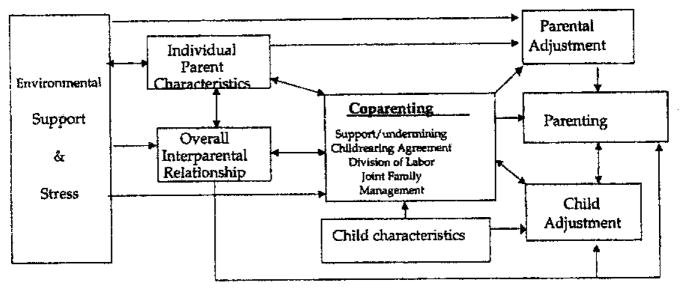

I now turn to a more macroscopic model of the antecedents and consequents of coparenting portrayed in Figure 2: The individual, family, and extra-familial factors that influence coparenting relationships, and some of the hypothesized mediating and moderating relationships that link coparenting to outcomes. This model draws on earlier frameworks developed by family scholars such as Belsky (1984) and P. A. Cowan (1988).

FIGURE 2.

Ecological Model of Coparenting

At this broader level, the four components of the coparenting relationship are now considered as an ensemble. In this model, the qualities of the coparenting relationship directly influence parenting and child adjustment, as well as indirectly through parental adjustment (see Grych & Clark, 1999). Parental adjustment is indexed by constructs such as parental efficacy, discussed previously, and depression specifically related to the strains of parenthood.4 Individual child factors, such as temperament, are also portrayed as influencing child adjustment.

This section describes the basic features of this ecological model, beginning first with the individual, family and extrafamilial influences on coparenting, and then turning to the mediating and moderating processes in which the coparenting relationship plays an important role.

Influences on Coparenting

Individual level influences

Parents’ individual characteristics influence both coparenting and the overall interparental relationship. Parents’ individual characteristics include factors such as attitudes (e.g., gender role expectations) and emotional and mental health. For example, depression or hostility in one or both parents may limit parents’ ability to express positive emotional support, engage in productive resolution of childrearing differences, and maintain boundaries such that children are not exposed to undue interparental hostility (Belsky & Hsieh, 1998).

Less obvious, perhaps, is the role that individual child factors may play in shaping the coparenting relationship. For example, difficult child temperament may induce increased stress and conflict in the coparenting relationship. Infants with a difficult temperament present challenges both for individual parents and for the coparenting team as a coordinated unit. Children with difficult temperament, by definition, are not as soothed as easily as other children, and thus many parenting strategies may generally seem not to work well with such children. As parents of temperamentally difficult children experience relatively more “failures” than “successes” compared to parents of children with easier temperaments, increased opportunities will arise for interparental criticism and undermining. Furthermore, as the temperamentally more difficult child will more often place parents in a situation where they need to evaluate their strategies and re-commit to one or choose a new approach, parents’ disagreement on a childrearing issue will become salient and lead to heightened difficulties. Although there is not yet empirical support for the influence of child temperament on the coparenting relationship, there is evidence of the influence of child problems on the couple relationship (Mash, 1984). It is expected that a more precise investigation would find that child temperament and difficult behavior are more closely linked to the coparenting relationship (due to domain specificity). Thus, the coparenting relationship is expected to partly mediate the influence of child temperament on the couple relationship and on parenting.

In addition to this evocative effect of child temperament on coparenting, infants and children may also play an active role influencing the interaction patterns and degree of harmony in the coparental relationship. For example, infants as young as 3 months appear to vary in their proclivity to engage both parents simultaneously versus paying attention to one parent at a time (Fivaz-Depeursinge & Corboz-Warnery, 1999; McHale & Fivaz-Depeursinge, 1999; also see Tremblay-Leveau, 1999). It is also likely that older children may actively promote interparental teamwork (e.g., “don’t yell at mom — both of you guys need a time-out”), whereas others may find security in joining one parent in a coalition against the other. Although the links between child characteristics and triadic patterns of family interaction are often conceptualized in terms of the influence such patterns exert on children, it would be interesting for researchers to examine longitudinal associations in the opposite direction — assessing the influence that children have on family systems.

Family level influences

The most important family factor influencing coparenting relations is the dyadic-level overall interparental relationship (Kitzmann, 2000). For example, new coparents bring to the coparenting relationship their existing ability to demonstrate support and respect for each other and discuss disagreements. However, Figure 2 portrays this path as bi-directional: Once formed, the coparental relationship becomes centrally important to the daily experience of the coparents and the family, and influences the course of the overall interparental relationship (e.g., Belsky & Hsieh, 1998). Coparental miscoordination and friction, when acute or chronic, spills over and leads to greater hostility, conflict, and dissatisfaction in the overall relationship. Three studies have documented this association longitudinally (Belsky & Hsieh, 1998; Hetherington et al., 1999; Schoppe, Mangelsdorf, Frosch, & McHale, 2001). One of these studies tested both potential directional paths: After controlling for stabilities over time, coparenting at child age of 6 months influenced marital relationships at 3 years, but marital relationships at 6 months did not predict co-parenting at 3 years (Schoppe et al., 2001).

Extrafamilial level influences

The inclusion of extrafamilial factors in the model is based on a stress-coping perspective (Lerman & Glanz, 1997). It is assumed that the maintenance of coordinated childrearing strategies and mutual support requires some degree of engagement and effort for all coparents. Stress on the individual coparents, dyad, or family will tend to undermine — and support will tend to bolster coparents’ ability — to maintain coordination and harmony. Here I mention one representative source of support and one examplar of stress.

Family researchers have been interested in the role of social support in bolstering the competence of parents. Extrafamilial social support may be a general protective factor (Johnson & Sarason, 1978) facilitating the coping of families experiencing stress. In this model, such social support is viewed as enhancing the coparenting relationship both directly and indirectly through parent characteristics and the overall interparental relationship. Furthermore, independent of the coparenting relationship, extrafamilial social support is expected to enhance parental adjustment.

In terms of stress, economic stress has frequently captured the attention of researchers. There are at least three ways of conceptualizing stress in the economic sphere, and each may affect coparenting relations and the relevant family outcomes. First, economic stress as a result of having a low level of financial resources has been shown to negatively affect parental and couple well-being (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, et al., 1994; Vinokur, Price, & Caplan, 1996; Voydanoff & Donnelly, 1988). Socioeconomic disadvantage is a risk factor for conduct disorder (Lahey, Miller, Gordon, & Riley, 1999), and family relationships mediate the link between economic stress and child behavior problems (Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, et al., 1992,1993; Crouter, Bumpus, Maguire, & McHale, 1999). Second, stress experienced at work can lead to increased distress in family relationships (Perry-Jenkins, Repetti, & Crouter, 2000). Third, work and family spheres compete for parents’ time, and such tensions contribute to interparental conflicts (Guelzow, Bird, & Koball, 1991; Menaghan, 1991; Thompson, 1997; Volling & Belsky, 1992). For example, parent involvement in paid work influences the actual division of labor arrangements inside the home: When wives work outside the home, fathers tend to be more involved in chores and childcare (Ishii-Kuntz & Coltrane, 1992), However, dual-earner fathers are less sensitive to sons and more negative to wives compared to sole breadwinners (Braungart-Rieker, Courtney, & Garwood, 1999; Crouter, Perry-Jenkins, Huston, & McHale, 1987; also see Easterbrooks & Goldberg, 1985). Crouter et al. (1987) suggested that, in general, husbands’ may react negatively to the “push” to be involved in childcare in dual-earner couples and/or the conflictual interactions that stem from wives’ efforts to achieve that end (also see Grych & Clark, 1999).

In sum, there is a wide range of individual, family, and extrafamilial influences on coparenting. Some of these influences are likely highly stable (e.g. parent personality features), whereas others may be more likely to fluctuate (e.g. economic stress). It would be quite interesting for investigators to examine the influences of various factors on coparenting components in some detail: For example, which components of coparenting are affected by extra-familial social support? It may be that some aspects of social support, such as emotional support, might contribute to coparental support, whereas instrumental social support might relieve some of the pressure on division of labor issues and thus improve relations in that area.

Mediating and Moderating Pathways

Mediation

The ecological model portrays the coparenting relationship as central to the network of associations involving the couple relationship, parenting, and child outcomes. Coparenting is viewed in this model as a mediator of influence on important family outcomes, which logically follows from research cited previously indicating mat multiple factors influence coparenting and that coparenting influences multiple parent and child outcomes. For example, several studies have demonstrated that the coparenting relationship at least partly mediates the link between the overall interparental relationship and warm, sensitive parenting both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Feinberg et al., 2003; Floyd, Gilliom, & Costigan, 1998; Gonzales, Pitts, Hill, & Roosa, 2000; also see Belsky & Hsieh, 1998). In one study, the association between interparental conflict and parenting became nonsignificant when coparenting was added to the model (Margolin et al, 2001).

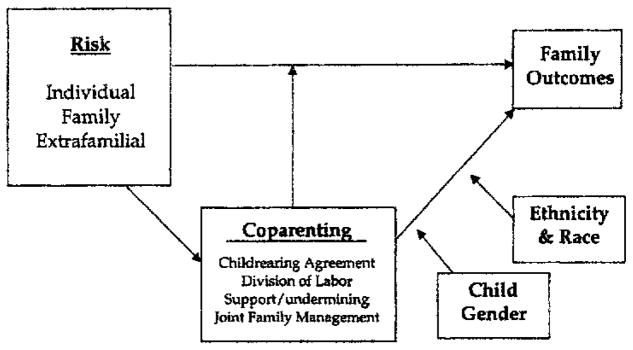

Viewing the coparenting relationship as a mediator may help us understand how individual parent characteristics are filtered through the family system and ultimately affect children. For example, research suggests that coparenting partly mediates the influence of individual parent or child characteristics on parenting and child adjustment (see Belsky & Hsieh, 1998; Lau & Pun, 1999; Martin & Halverson, 1991; Mash, 1984). Thus, a mother who is depressed may not offer the father much coparental support, which then negatively affects the father’s parental efficacy and parenting. In addition, coparenting likely partly mediates the influence of the extra-familial or environmental factors discussed previously on relevant family outcomes (i.e., lack of social support, economic and work stress). Figure 3 depicts these mediatiortal pathways in simplified form, grouping individual, family, and extrafamilial factors under the heading of “risk.”

FIGURE 3.

Mediating and moderating pathways: The mediating and moderating role of coparenting with respect to the influence of risk on family outcomes; and the moderating pathways of child gender and family ethnicity/race on the relation of coparenting with family outcomes.

Moderation

Moderators describe the conditions (who, when) under which a causal process occurs. There are two moderating questions regarding coparenting: Does coparenting moderate the relations between risk factors and family outcomes — for example, does the presence of positive coparenting attenuate the link between risk and outcomes? And, second, what factors affect (moderate) the influence of coparenting on parenting and child adjustment? With regard to this second question, it is common to begin the investigation of moderating factors by looking at structural, demo- graphic factors such as gender and race, Although I briefly explore gender and race as moderators, this is only a prelude to the development of a more process-oriented understanding of what factors influence the salience of coparenting for family outcomes.

Coparenting moderating the effect of risk

In a risk and protective factor framework, protective factors can be viewed as buffering or protecting individuals from the effects of negative influences. Viewed as a protective factor, closely coordinated coparenting relationships may moderate the relation between risk and family outcomes. Floyd et al. (1998) suggested that positive coparenting may protect parenting quality and child adjustment from the negative effects of depression in one parent. Positive coparenting would both enhance a depressed parent’s sense of support and efficacy, thus buffering parenting from the negative effects of depression, and protect the child from the negativity in the couple relationship that frequently is associated with parental depression. Similarly, a strong coparenting relationship may attenuate the effects of couple conflict on children (Abidin & Brunner, 1995; McHale, 1995). Thus, high levels of hostile couple conflict may be detrimental only when coparenting quality is low, not when it is high. Figure 3 portrays this moderator relation. Despite the suggestions of coparenting researchers, there is as yet limited evidence for the moderating role of coparenting (but see Feinberg, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2003).

Child gender as a moderator

Given the evidence of differences between young boys’ and girls’ adjustment and developmental trajectories (Emery & O’Leary, 1984; Keenan & Shaw, 1997; Spieker, Larson, Lewis, Keller, & Gilchrist, 1999), child gender may moderate the relation between coparenting and family outcomes. For both two-parent and divorced families, however, several meta-analyses suggest that the moderating effect of child gender on the links between the couple relationship and parenting, parent – child relationships, or child adjustment are minimal (Amato & Keith, 1991a, 1991b; Erel & Burman, 1995; Whiteside & Becker, 2000). Findings in the area of coparenting relations have been mixed, with some studies demonstrating no moderating effects and others demonstrating effects but with limited consistency across studies (Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1991; Floyd et al.,1998; Floyd & Zmich, 1991; Margolin et ai, 2001; McHale, 1995).

One interpretation of some of the positive findings of gender moderating coparenting involves fathers’ differential investment in boys versus girls (Cox, Owen, Lewis, & Henderson, 1989; Orbuch, Thornton, & Cancio, 2000). For example, McHale (1995) reported that child gender moderates the link between marital distress and disrupted coparenting: High marital distress is linked to conflictual coparenting in families with boys, but to asymmetry during triadic interaction for families with girls. It may be that in families where there is underlying coparental negativity, fathers of boys remain engaged leading to coparenting conflict, whereas fathers of girls may withdraw leading to asymmetrical interaction. Differential father investment may also help interpret the finding by Margolin et al. (2001) that, in a pooled sample of families with preschool and preadolescent children, mothers triangulated sons into interparental conflicts more than they did daughters, but fathers triangulated sons and daughters to an equivalent degree. Mothers’ greater triangulation of sons than daughters may reflect the fact that involving sons is a more effective means of reaching fathers (even in a negative manner) than involving daughters because of fathers’ greater interest in sons. Given mothers’ equal investment to boys and girls, then, fathers would be equally able to reach mothers through triangulating either boys or girls.

Ethnic and racial background as a moderator

As noted previously, there are few data available yet addressing the issue of coparenting across diverse ethnic and racial groups. Some research indicates that there are modest differences across groups in the coparenting division of labor. African American husbands are slightly more involved in household chores and childcare than European American husbands — although African American wives, like European American wives, are responsible for the majority of such tasks (McLoyd, 1993; Shelton & John, 1993). Despite the “machismo” stereotype, Latin fathers are more likely to participate in traditionally female household tasks — although the total amount of time they spend on household work and their attitudes toward the division of labor are not different from European American fathers (McLoyd, 1993; Shelton & John, 1993).

How these differences in the objective division of labor play into coparenting relationships is not clear. If the magnitudes of the differences across groups are salient to mothers, it may be that African American and Latin mothers are somewhat more satisfied with the coparenting division of labor than are European American mothers. However, it may also be that expectations are set with reference to cultural, family and neighborhood norms, and thus differences in average levels of father participation across racial and ethnic groups would be reflected in corresponding differences in parents’ expectations across groups.

Diversity across families may also affect how children experience, and thus are affected by, coparenting difficulty. For example, the degree to which nuclear families and children are embedded in extended family and neighborhood support systems may diminish the impact of interparental conflict for children of color compared to European American children (McLoyd et al., 2000). Although the evidence is mixed to date, the proposition could be broadened: Nuclear family insularity may moderate the relations of coparenting generally to child adjustment. The underlying rationale is that where children are integrated into a broad system of extended family and community relationships, the features of relationships in the nuclear family may be less salient than where the child’s social world is comprised mainly of the nuclear family.

Summary

Considering this ecological model as a whole, the centrality of coparenting in this framework is due to two different mechanisms. First, coparenting relations directly influence both outcomes and the associations between other factors and outcomes. There is a need for further work not only to further investigate and document the direct and moderating effects of coparenting, but also to understand the processes through which these effects occur. In the context of a larger research study, it is fairly low-cost and easy to include analyses of moderators such as child gender or race. The collection of data on such structural and demographic characteristics is fairly simple and inexpensive. However, to make progress in understanding the moderating role of coparenting relations, a more dedicated approach will need to be adopted in which marker variables such as child gender and race are replaced by more process-oriented and difficult to assess characteristics, such as parental investment, gender ideology, or the density of extended family network relations.

Second, the centrality of coparenting relations is partly due to its role as mediator or transmitter of influence from other factors to outcomes. It is worth pointing out that the importance of the coparenting relationship as a mediator emerges from its susceptibility to the influence of other factors. In other words, although we often view the importance or power of a factor as due to the influence it exerts, it is also true that the importance of a factor may relate to its ability to be influenced by other factors. In social networks, for example, one source of power that accrues to actors is the extent mat they “broker” relationships between other actors (Freeman, 1979). A topic for future research would be the extent to which coparenting relations are susceptible to other factors over the developmental course of the family, which is related to the final section of this article.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS: THE DEVELOPMENT OF COPARENTING

The network of family relationships becomes much more complex after the birth of a first child (e.g., Lewis, Owen, & Cox, 1988). From a single dyadic couple relationship, the family expands to include two parent – child relationships, a triadic relational system, and a new coparenting component of the couple relationship. Although the transition to parenthood has been a focus of many studies (e.g., Demo & Cox, 2000), much of the research has focused on the effects of this period on the couple relationship and the well-being of the individual parents. The processes through which a couple-relationship becomes part of a differentiated family system, and the development of the coparenting relationship in particular, have not been adequately researched.

Investigation of the development of coparenting could address several new issues: For example, it is unknown how patterns of early coparenting difficulty are related to long-term outcomes. Within a diathesis-stress framework, early but transient coparenting difficulty may be a sign of vulnerability predicting later difficulty. However, such conflict could reflect fundamental reworking of expectations and partnership arrangements that would lead to longer-term satisfaction. Suggestive evidence for such a process was found by the Cowans: Men in their couples’ intervention reported more dissatisfaction with the division of labor at 6 months postpartum, but more satisfaction at 18 months, than men in the control condition (Cowan & Cowan, 1987). The intervention men wanted to be more involved with childcare than they were at 6 months. Their initial dissatisfaction may have led to further work in the coparenting relationship that facilitated greater satisfaction at 18 months.

A second set of issues concerns the stability (maintenance of rank order over time) of the coparenting relationship. To what extent is there rigidity or canalization of the coparenting relationship; in other words, if coparents do not address and resolve early childrearing differences, can they approach these issues anew later on? For example, do established patterns and levels of satisfaction with the division of labor become rigid, and, if unsatisfactory, a source of chronic stress? Or does the division of labor arrangement become reworked as the tasks and responsibilities change as children develop? It may be that some mothers are disappointed with fathers’ involvement in the bodily care of infants, but then later become more satisfied with fathers’ engagement in play, homework, and leisure activities during middle childhood. Even if the division of labor issues are not so troublesome later on, it may be that early dissatisfaction has consequences for mothers’ adjustment to parenthood, parenting, or the coparenting relationship — and these consequences are not undone when such fathers take a more active role in later childrearing tasks.

A third set of questions relates to the normative course of coparenting, including continuity in the coparenting relationship. It seems that during the second year postpartum, while the frequency of supportive coparenting interactions remains stable, the average frequency of unsupportive interactions decreases (Gable et al., 1995). However, further longitudinal study of coparenting through middle childhood and adolescence has not been conducted. Given the fundamental changes in parenting and family relationships across this period (Baurnrind, 1991), it is likely mat the form and meaning of coparenting change as well. For example, it is possible that after the transition period, resolutions of division of labor issues — whether satisfactory or not — are in place; thus change in parental adjustment and parenting may then be influenced more strongly by other coparenting components. In addition, during the toddler and preschool periods, the joint management of family interaction (including triangulation and coalitions) may become increasingly salient for parenting and for children’s social-emotional development.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has developed conceptual frameworks for understanding coparenting that will hopefully be of benefit both to basic and applied researchers. The multidimensional coparenting framework presented here, and the ecological model that portrays coparenting as a proximal influence on parental adjustment, parenting, and child development, offers several exciting opportunities for research. Indeed, there is a great deal of conceptual and empirical work to be done to more fully understand the internal structure, influences on, and developmental course of coparenting. One area that has received little attention in this article, and in research on coparenting to date, are the relations of coparenting in individual families and larger social institutions and systems. For example, the nature and importance of coparenting in each family is likely affected by individual beliefs, but individual beliefs are formed in the context of larger cultural themes, institutional arrangements (e.g. work – family policies), and local reference groups. Recognition of these levels of influence on family relationships are important not only to foster a comprehensive understanding of the determinants of family life, but also to ensure we do not neglect potential intervention targets at the level of the communities or social institutions in our eagerness to support individual families,

Despite the additional research that is called for, enough is known to begin efforts to enhance coparenting relationships through both universal interventions (e.g. education, mass media, new baby literature) and targeted interventions with diverse families. Such interventions will have the potential for utilizing what we do know about the links between the couple relationship and child outcomes, and thus bridge the gap between couple relationship programs and parenting/parent – child programs. In this way, family systems theory and research may provide the basis for a whole-family approach to family support, prevention, and treatment.

Acknowledgments

I thank George Howe, Mark Greenberg, Susan McHale, James McHale, Phil and Carolyn Cowan, Marc Bornstein, and several anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this article.

Footnotes

Although we now commonly term the two-parent, nuclear family the “traditional” form, it is worth noting that this tradition of segmented, discrete nuclear families is relatively recent

The relations between social support and social-emotional health are probably reciprocal, as pointed out by Carolyn Cowan. Whereas social support may enhance well-being and adjustment, well-adjusted and competent individuals and families are probably better skilled and able to seek out, elicit, and accept support.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that emotion processes should be considered.

Pre-existing depression, or depression arising from other life experiences, would be best captured in the individual parent characteristics construct.

References

- Abidin RR, Brunner JF. Development of a Parenting Alliance Inventory. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24(1):31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrons CR. The continuing coparental relationship between divorced spouses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1981;51(3):415–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1981.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldous J, Mulligan GM, Bjarnason T. Fathering over time: What makes the difference? Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1998;60:809–820. [Google Scholar]

- Alien SM, Hawkins AJ. Maternal gatekeeping: Mother’s beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1999;61:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Marital conflict, the parent-child relationship and child self-esteem. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family & Child Studies. 1986;35(3):403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991a;110(1):26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Separation from a parent during childhood and adult socioeconomic attainment. Social Forces. 1991b;70(1):187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(5):729–735. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent–adolescent communication and the Circumplex Model. Child Development. 1985;56:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Hetherington EM, editors. Family transitions. Advances in family research series. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. pp. 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bearss KE, Eyberg S. A test of the parenting alliance theory. Early Education & Development. 1998;9(2):179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The interrelation of parental and spousal behavior during infancy in traditional nuclear families: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1979;41:749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Early human experience: A family perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55(1):83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Crnic K, Gable S. The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development. 1995;66(3):629–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh KH. Patterns of marital change during the early childhood years: Parent personality, coparenting, and division-of-labor correlates. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(4):511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Putnam S, Crnic K. Coparenting, parenting, and early emotional development. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. New directions for child development. Vol. 74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Rovine M, Fish M. The developing family system. In: Megan ET, Gunnar R, editors. Systems and development. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Vol. 22. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1989. pp. 119–166. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Woodworth S, Crnic K. Trouble in the second year: Three questions about family interaction. Child Development. 1996;67:556–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller HB. Preventing paternal deprivation. In: Shapiro JL, Diamond MJ, editors. Becoming a father: Contemporary, social, developmental, and clinical perspectives. Springer series, focus on men. Vol. 8. New York: Springer; 1995. pp. 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J, Morrison A. Parental agreement—disagreement on childrearing orientations and gender-related personality correlates in children. Child Development. 1981;52:965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Parenting infants. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Vol. 3: Status and social conditions of parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker J, Courtney S, Garwood MM. Mother- and father-infant attachment Families in context. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13(4):535–553. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol MM, Gallagher JJ, Schopler E. Mothers and fathers of young developmentally disabled and nondisabled boys: Adaptation and spousal support. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24(3):441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Flor D, Neubaum E. Coparenting processes and child competence among rural African–American families. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Families, risk, and competence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1998. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Coparenting, family interactions, and competence among African American youths. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. New directions for child development. Vol. 74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Pellegrini AD, Sigel IE. Marital quality and mother–child and father–child interactions with school-aged children. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(3):291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. The social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan CM, Maccoby EE, Dornbusch SM. Caught between parents: Adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Development. 1991;62(5):1008–1029. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler C, Krishnakumar A, Stone G, Anthony C, Pemberton S, Gerard J, et al. Interparental conflict styles and youth problem behaviors: A two-sample replication study. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1998;60(1):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Camara KA, Resnick G. Styles of conflict resolution and cooperation between divorced parents: Effects on child behavior and adjustment. American journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59(4):560–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb02747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Heavey CL. Gender and social structure in the demand/withdraw pattern of marital conflict. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;59(1):73–81. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Margolin G. Conflict and alliance in distressed and non-distressed families. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families. Oxford: Clarendon; 1988. pp. 263–282. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, et al. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63(3):526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, et al. Family economic stress and adjustment of early adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(2):206–219. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, et al. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65(2):541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP. Working with men becoming fathers: The impact of a couples group intervention. In: Bronstein P, Cowan CP, editors. Fatherhood today: Men’s changing role in the family. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1988. pp. 276–298. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Men’s involvement in parenthood: Identifying the antecedents and understanding the barriers. In: Berman PW, Pederson FA, editors. Men’s transitions to parenthood: Longitudinal studies of early family experience. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. pp. 145–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Who does what when partners become parents: Implications for men, women, and marriage. Marriage & Family Review. 1988;12(3–4):105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan P, McHale J. Coparenting in a family context: Emerging achievements, current dilemmas and future directions. In: McHale JP, Cowan PA, editors. Understanding how family-level dynamics affect children’s development: Studies of two-parent families. New directions for child development. Vol. 74. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA. Developmental psychopathology: A nine-ceil map of the territory. ST -New directions for child development, No. 39. In: Nannis ED, Cowan PA, editors. Developmental psychopathology and its treatment. New directions for child development, No. 39. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988. pp. 5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Owen MT, Lewis JM, Henderson VK. Marriage, adult adjustment, and early parenting. Child Development. 1989;60:1015–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]