Abstract

This study was a crosscultural replication of a study that investigated therapist adherence to behavioral interventions as a result of an intensive quality assurance system which was integrated into Multisystemic Therapy. Thirty-three therapists and eight supervisors participated in the study and were block randomized to either an Intensive Quality Assurance or a Workshop Only condition. Twenty-one of these therapists treated 41 cannabis-abusing adolescents and their families. Therapist adherence and youth drug screens were collected during a five-month baseline period prior to the workshop on contingency management and during 12 months post workshop. The results replicated the previous finding that therapist adherence to the cognitive-behavioral interventions, but not to contingency management, showed a strong positive difference in trend in favor of the intensive quality assurance condition. While the clinical impact of such quality assurance may be delayed and remains to be demonstrated, cannabis abstinence increased as a function of time in therapy, and was more likely with stronger therapy adherence to contingency management, but did not differ across quality assurance interventions.

Keywords: adolescent substance abuse, quality assurance, contingency management, cognitive-behavioral techniques, effective implementation, crosscultural replication

Over the last several years, the focus on the development of evidence-based practices in the fields of medical and behavioral health has led to an increasing concern regarding the related issue of effective implementation of such practices. Although efficacious interventions are crucial to improved services, it is also realized that no matter how efficacious interventions are, their impact will be limited if not implemented with fidelity. Hence, the first wave of research on developing efficacious treatments has been followed by a second wave of research on the effective implementation of such treatments (e.g., Barlow, Levitt, & Bufka, 1999; Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005).

One of the main recommended strategies to enhance treatment fidelity is to implement strong quality assurance procedures (Chamberlain, 2003; Olds, Hill, O’Brien, Racine, & Moritz, 2003). A number of non-experimental studies have suggested that intensive training can increase treatment fidelity to substance abuse and violence prevention treatment protocols (e.g., Mihalic & Irwin, 2003; Miller & Mount, 2001), and that feedback to therapists may facilitate the implementation of efficacious interventions even further (Andrzejewski, Kirby, Morral, & Iguchi, 2001). Although few experimental studies have been conducted to study methods to improve implementation fidelity, the results of those that have been undertaken strongly indicate that intensive and persistent training efforts with consistent feedback can successfully enhance adoption and treatment fidelity to research-based interventions (Kelly et al., 2000; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005).

Nearly a decade ago, the Norwegian Ministry of Child and Family Affairs launched a major initiative for dissemination of research-based interventions. The focus has been on the most costly antisocial behavior in children and youths (Biglan & Ogden, 2008; Ogden, Christensen, Sheidow, & Holth, 2008). One of the main dissemination efforts within this initiative has been for Multisystemic Therapy (MST) for adolescents (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998). By 2007, MST teams were established across Norway, with 23 teams (86 therapists and 25 supervisors). In a randomized MST trial during the first year of implementation (Ogden & Halliday-Boykins, 2004), substance use was reported as one of the referral reasons for 50% of the youths, although substance use outcomes were not specifically reported.

Although MST substance-related outcomes have been generally favorable (Sheidow & Henggeler, 2008), MST has not typically focused directly on substance use itself, but on change in youths’ family, peer, and school relations that have been correlated with substance use (e.g., Henggeler, Melton, & Smith, 1992). In order to enhance substance-related treatment outcome for youths referred to MST services, attempts have recently been made to focus more specifically and intensively on substance use behavior by integrating contingency management (CM) and cognitive-behavioral techniques (CBT) into MST (Henggeler et al., 2006; Randall, Henggeler, Cunningham, Rowland, & Swenson, 2001). Some of the main characteristics of CM that may add to the effects of MST are that it includes the frequent, but random, collection of biological drug screens and the delivery of positive reinforcers (vouchers or points to be exchanged for specific, individualized goods or preferred activities) contingent upon clean screens; the use of detailed functional analyses of interrelations between drug-related behavior as well as behavior that is not compatible with drug use, and its antecedents and consequences; and self-management training and planning based upon such functional analyses (Cunningham et al., 2003).

For several reasons, CM/CBT seems particularly suited as a supplement to MST for adolescents with substance use problems: First, the integration of CM/CBT into MST is consistent with all five factors identified in diffusion theory (Rogers, 1995) as important for facilitating implementation of an innovation: CM/CBT (1) can be tried out on a limited basis, (2) is focused on and produces easily observable results, (3) has the advantage of being extensively validated as a treatment for substance use (e.g., Higgins, Heil, & Lussier, 2004; Petry, 2000; Silverman, 2004), (4) is not overly complex, and (5) is compatible with existing practices and values in MST, such as pragmatic goal-directedness, the use of functional analyses, and a focus on empirical validation. Second, previous studies have indicated that CM/CB specifically directed towards substance use can be a valuable addition to the more ecologically oriented MST approach (Henggeler et al., 2006; Randall et al., 2001).

In a recent implementation study in Connecticut (Henggeler, Sheidow, Cunningham, Donohue, & Ford, 2008), MST therapists were exposed to either of two different levels of quality assurance following a two-day workshop on CM/CBT for youth marijuana use. MST therapists were assigned to either a Workshop Only (WSO) training condition or a workshop followed by Intensive Quality Assurance (IQA) training condition. Therapist adherence to CM was measured by monthly youth and caregiver reports on one subscale assessing therapists’ implementation of substance use monitoring techniques, while another subscale assessed therapist adherence to CBT, such as identifying triggers and developing the youth’s drug refusal and drug avoidance skills (referred to as cognitive behavioral techniques). Based on both youth and caregiver reports, therapist fidelity to CBT was initially more enhanced by IQA than by WSO, and according to the youth reports, this enhanced fidelity was sustained. However, neither youths nor caregivers reported an enhanced therapist fidelity to CM techniques in the IQA condition relative to WSO.

The present study aimed to replicate the procedures for integrating CM/CBT with MST used in the Henggeler et al. (2008) study with a Norwegian population of MST therapists working with cannabis-abusing youths and their families. Further, the analyses of the present study were extended to include drug use data as well as data on demographic and organizational variables.

The main research question addressed in the present study was whether a specific, intensive quality assurance (IQA) intervention would enhance therapist fidelity to CM/CBT above that obtained by having therapists attend a CM/CBT workshop (Workshop Only; WSO). In order to assess the clinical significance of enhanced therapist adherence, a second research question was whether increased therapist adherence to CM and/or CBT was associated with increased cannabis abstinence in the youths. Finally, if the IQA intervention enhanced therapist fidelity to CM/CBT above that of the WSO condition, a third question was whether that differential gain in treatment fidelity obtained by the IQA would be associated with an analogous reduction in cannabis use by the participating youths.

Method

Design and Participants

Participants recruited for this study included MST therapists, the substance-abusing youth they were treating, and the youth’s primary caregiver. Eight MST teams were recruited for participation and served as a foundation for this study. The study included a 5-month baseline period and a 12-month follow-up period. Throughout both periods, therapists referred families they were treating, and both therapists and families were assessed after consenting to participate and monthly. At the end of the baseline period, all therapists and supervisors attended a CM/CBT workshop. Immediately following the workshop, MST supervisors and their corresponding MST teams were block randomized to the intensive quality assurance (IQA) group or to the workshop only (WSO) group. Some MST teams were co-located or located geographically very near other teams. Two such clusters, each consisting of three teams, were naturally close collaborators and were therefore randomized together into either the IQA or WSO condition to avoid possible contamination. Finally, the last two teams were individually randomized into the two conditions. Thus, the condition sizes were approximately equal. All consent and research procedures were approved by the National Committee for Research Ethics.

MST Therapists and Supervisors

MST teams were eligible for participation on the basis of three criteria: (1) the teams treated a relatively large number of youths with drug use over the past one-year period; (2) the national MST program director identified the teams as stable, with minimal turn-over among the supervisors and therapists; and (3) the teams had high levels of adherence based on the monthly MST fidelity assessment collected routinely for all MST teams nationwide. Eight MST teams and their provider organizations were invited to participate, and all agreed to allow team members to participate. All of the clinicians, 33 therapists and 8 supervisors, who were invited consented to participate in the study.

Twelve of the 33 therapists who agreed to participate in the study did not refer any youths and families to the study. Hence, the present analyses include data from 21 MST therapists: 13 in the IQA condition and 8 in the WSO condition. Therapists completed a baseline interview concerning demographic information and organizational variables, and then were assessed monthly regarding their treatment fidelity for each family they currently had in the study. Assessment instruments are described in subsequent sections.

The majority of the 21 therapists were women (57%), with ages ranging from 31 to 59 years (M = 41.3 years, SD =7 years). Regarding ethnicity, the sample was very homogenous, with 95% Caucasian. With respect to formal education, 52% held a bachelor degree, and 48% had minimum a Master’s degree or equivalent. Ninety percent of the clinicians had more than one year of practice as an MST therapist. The two groups of therapists (IQA and WSO) did not differ significantly on these demographic and experience variables.

Youths and Families

Throughout the five-month baseline period as well as throughout the twelve month follow-up period, the therapists were requested to refer all youths with a suspected substance use disorder for possible participation in the study. The therapist asked the family for permission and, if granted, forwarded the contact information to the research staff. A research assistant contacted the family, provided written information about CM/CBT and the research project, and obtained informed consent from the parents and assent from the adolescent to participate in the study. Upon obtaining consent, the research assistant proceeded with a demographics interview and a screening instrument. The substance abuse sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) were administered independently to the youth and to the primary caregiver (with respect to the youth’s symptoms). If either of these reports met criteria for cannabis abuse or dependence, the family met criteria for continued study participation and was asked to complete a battery of baseline measures. For the next 4 months or, if treatment was terminated earlier, for the duration of the treatment, the youth and the primary caregiver were assessed monthly. In total, 44 families were referred to the study and 41 of these were eligible, i.e., the youths were between 13 and 17 years of age and met the diagnostic criteria. Of these 41, 100% consented to participate. Families were compensated 250 Norwegian Kroner (approximately $40) for the initial baseline assessment and 150 Norwegian Kroner (approximately $25) for each subsequent assessment.

Of the 41 families with substance abusing youths participating in the current study, 25 were being treated by therapists in the IQA condition and 16 were being treated by therapists in the WSO condition. Youths ranged from 13 to 17 years of age (M = 15 years, 10 months, SD = 14 months), and 65% were male. Ethnicity was generally reflective of the Norwegian population, with the ethnicity for 38 being white Caucasian, two Asian Norwegian, and one African Norwegian. All of the participating youths met SCID-based diagnostic criteria for substance abuse or dependence over the last year. Also, 37% of the youths had a history of previous treatment for mental health and/or substance abuse problems. Approximately 78% of the youths were in regular school settings. The average age of the caregiver respondents was 40 years and 9 months, 78% were female, and their median level of education was 12 years. Mean annual family income was 375,610 Norwegian Kroner (SD = 206,116), equivalent to approximately 65,000 USD. Adjusting for the higher portion of single parent households in the sample relative to the national population at large, the annual income of the participating families was approximately 15% below the national mean. Youths and caregivers in the IQA and WSO groups did not differ statistically significantly on these demographic and clinical variables.

Interventions with Youths and Families

The focus of the present study was MST therapists’ adherence to CM/CBT procedures when treating cannabis abusing adolescents and their families. The treatment procedures are detailed in separate treatment manuals for MST (1998) and for using CM/CBT procedures within the context of MST (Cunningham et al., 2003). However, a brief description of MST interventions and the basic components of the CM/CBT protocol are presented here to provide an overview of the clinical context of the study.

Multisystemic Therapy (MST)

MST is a comprehensive community-based treatment for families with adolescents at risk for out of home placement because they display serious behavioral problems (e.g., theft, vandalism, violence, drug abuse). Treatment is delivered in the family’s natural ecology (e.g., home, school, community) and typically aims to advance caregiver discipline practices, promote family affective relations, reduce youth contact with deviant peers, increase youth interaction with prosocial peers, improve youth school or work performance, engage youth in prosocial leisure activities, and develop a local support network of extended family, friends, and neighbors to facilitate and maintain changes. To produce these gains, MST integrates specific treatment techniques from those therapies that have the most solid empirical support, including behavioral, cognitive behavioral, and the pragmatic family therapies. Findings from 15 published randomized clinical trials have led several federal entities in the US (e.g., National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1999), leading reviewers (e.g., Kazdin & Weisz, 1998), and consumer groups (e.g., National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2003) to identify MST as an empirically supported intervention for youths with serious antisocial behavior (see Henggeler, Sheidow, & Lee, 2007).

Contingency Management (CM) and Cognitive-Behavioral Techniques (CBT)

CM treatment for substance abuse is empirically well-supported (e.g., Petry, 2000; Silverman, 2004; Silverman, Robles, Mudric, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2004). Although several variations of CM exist, the common component consists of providing concrete rewards for behavior that is incompatible with substance use. CM interventions have often incorporated cognitive-behavioral techniques, and the CM components utilized in the present study primarily were derived from the work of Budney and Higgins (1998) with adults and from the work of Donohue and Azrin (2001) with adolescents. As specified in a treatment manual (Cunningham et al., 2003), the CM component added to MST in the present study was a voucher system that rewarded clean drug screens. The added cognitive-behavioral component consisted of (1) a detailed functional analysis of behavior related to substance use, which served as the basis for (2) self-management planning, such as avoiding and tackling triggers and practicing drug refusal skills. In order to be able to deliver contingent consequences without delay, the therapists and caregivers collected urine specimen from the youth twice a week, using instant test cups (Integrated EZ Split Key Cup 6 Panel Drug Test for THC, Cocaine, Amphetamine, Methamphetamine, Opiate, and Benzodiazepines). The reward system was a three-level escalating voucher-based schedule in which gradually more points could be earned at successive levels to be reached after consecutive weeks with clean urine screens. Points were exchangeable in rewards that were identified by the youth and caregivers and described in a reward menu. Rewards could typically include activities (e.g., driving), social events (e.g., having friends visiting), items (such as new clothes, cell phone or CDs), or privileges (e.g., extended curfew, favourite meals). Negative consequences of positive drug screens included a drop down to a lower level on the reward system as well as the loss of privileges (e.g., restrictions on transportation, new clothes, and curfew).

Consistent with MST treatment principles, the youth’s caregivers participated in completing the functional analyses, in the subsequent planning of interventions, and in the monitoring of the self-management and substance use outcomes for the youths. For each participating youth, the therapist (regardless of whether in the WSO or in the IQA group) had access to Nkr. 1500 (approximately $250) to facilitate treatment goals.

Training Interventions for Therapists

Workshop on CM/CBT

Two experts in the use of CM procedures with substance abusing adolescents conducted the workshop. Both of these were also MST experts. The workshop objectives were to teach each of the component CM/CBT intervention skills to the participating therapists and supervisors, and to prepare them to tackle challenges that typically arise when working with substance-abusing adolescents. Approximately 2 weeks prior to the workshop, each participant received and was asked to review a Norwegian translation of the manual Integrating Contingency Management into Multisystemic Therapy (Cunningham et al., 2003). The two-day workshop was organized according to the content areas of this manual, and included (1) a conceptual rationale for integrating CM/CBT into MST, (2) a description of the basic tenets of CM derived from behavior analysis, (3) a review of the empirical foundation for CM/CBT, and (4) a review of empirical support from a randomized clinical trial in which CM/CBT was incorporated into MST for juvenile delinquents with substance abuse (Henggeler et al., 2006). Further, the workshop provided a detailed review of the components of CM/CBT including drawing up contingency contracts and reward menus targeting substance use, conducting a functional analysis of drug use, using the results of such functional analyses to assist youth self-management planning, teaching drug refusal skills, and monitoring the youth’s substance use by collecting urine screens twice a week. Further, the workshop incorporated demonstrations of each treatment component through small-group exercises and role-plays in which the participants practiced the implementation of components and received corrective feedback and positive reinforcement. Intensive Quality Assurance (IQA). An intensive quality assurance system related to CM/CBT was integrated into the standard MST quality assurance system (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2002; Schoenwald, 2008; Strother, Swenson, & Schoenwald, 1998). This quality assurance includes manualized components related to treatment, supervision, expert consultation (Henggeler et al., 1998), organizational support (Strother et al., 1998), and ongoing training, such as quarterly booster sessions for therapists and supervisors. In addition to receiving training and resources during the workshop, supervisors in the IQA group were encouraged to use specific strategies to sustain therapists’ use of CM/CBT interventions, such as requesting that therapists practice the components of treatment implementation during supervision sessions.

Research Procedures

Independent Variables

Because assignment to conditions occurred at the conclusion of the workshop, MST teams in the IQA and WSO conditions were not distinguished during the baseline period. Following the baseline period, the IQA condition involved two different elements that distinguished it from the WSO condition. First, the therapists and supervisors in the IQA condition received ongoing training and weekly consultations in CM/CBT, while the clinicians in the WSO condition only had phone and e-mail access to a CM/CBT expert consultant upon their own initiation. Second, only the IQA teams were provided quarterly CM/CBT booster sessions added onto the standard MST quarterly booster sessions.

Data Collection

At recruitment and at monthly intervals, research assistants collected measures of therapist CM implementation fidelity from caregivers and youths. Assessment sessions were arranged at a time and place (usually the family’s home) that was convenient for the family. Youth and caregiver were separated while completing their respective assessment interviews. Data were collected from therapists at recruitment and at monthly intervals by research assistants. Each month, therapists reported on their CM/CBT implementation for each study family they were treating. Note that although a particular family might participate for the 4 months of the family’s treatment episode, therapists participated throughout the 16-month-period that the study lasted.

Measurement

Therapist Adherence to CM/CBT

The main outcome of interest was the therapist implementation of CM and to CBT procedures. Monthly interviews with the caregiver, youth, and therapists included a 9-item CM/CBT therapist adherence measure (CM-TAM; Chapman, Sheidow, Henggeler, Halliday-Boykins, & Cunningham, 2008). The CM-TAM (see Appendix 1) is a 9-item questionnaire that was validated in three separate American studies (Chapman et al., 2008). In those studies, two hypothesized domains of cognitive-behavioral techniques (CBT) and monitoring (CM) were identified across caregiver, youth, and therapist reports. Five items of the CM-TAM were concerned with CBT, such as the identification of drug use triggers and development of drug refusal and avoidance skills, and these were combined into a single cognitive-behavioral component. Four items were combined into a CM component, and these included making sure that drug tests were completed, results of drug testing were provided to the family, abstinence from drugs was rewarded, and negative consequences were provided for drug use. For each component, a composite score was computed as the mean of the item scores from all informants. Each item was scored as: (1) Not at all, (2) A little, (3) Some, (4) Pretty Much, and (5) Very Much. Thus, for both components the possible range of scores was 1 to 5 (maximum treatment adherence).

Adolescent Drug Use

Use of cannabis was assessed monthly by the research staff through self reports as well as biological indices. The self reports were obtained using a Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) interview (Miller, 1991). During the recruitment interview, youths were asked to quantify specific amounts of substances consumed on a daily basis over the last 90 days, whereas in the succeeding monthly interviews, they were asked to report one month back. Monthly urine screens were analyzed by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Division of Forensic Toxicology and Drug Abuse, using the Emit II plus assay for Cannabinoids, which had a cutoff value of 20 ng/ml. The results of these monthly urine screens as well as the youths’ self reports were for research purposes only and were not accessible to therapists or families.

Analysis

Measurement Models for Therapist Adherence

A US validation paper (Chapman et al., 2008) of the CM-TAM indicated a two-dimensional structure, reflecting a Self Management (or CBT) factor and a CM factor. The present study was not designed to test measurement equivalence with the US version. Yet, as a crude test of equivalence, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted of the 9-item instrument using all available observations.

Intervention Effects

Intervention effects on therapist adherence were analyzed using mixed linear models for repeated measures in Stata using the xtmixed command. The study design included several levels of nested units, with 21 therapists nested within 8 teams, 41 families nested within 21 therapists, and up to five repeated observations nested within family. In addition, there were multiple raters within repeated observations. Although a five-level model (team-therapist-family-repeated measures-multiple raters) could potentially express all of this, the present sample size did not have sufficient information for the simultaneous estimation of these components. Since each report constitutes a unique combination of therapist and family, family is the natural cluster unit, with repeated measures and informants as nested units within family. Treating informant as the lowest level corresponds to viewing therapist adherence as a latent variable where between-informant variance is viewed as a residual component. This formulation is equivalent to using multiple informants as observed indicators in structural equation modeling (SEM).

Analyzing intervention effects with mixed linear models requires specification of a variance structure to account for the dependency between repeated observations across time. Based on a visual inspection of the families’ trajectories across time we decided to use a random intercept model with fixed effect of each family’s time in the study. This corresponds to a compound symmetry assumption, with a fixed intra-class correlation across repeated measurements (Singer & Willett, 2003).

To take into account measurement error we used multiple indicators of cannabis abstinence. Youths’ TLFB reports of cannabis use were recoded to obtain a dichotomous cannabis abstinence indicator. Reports over a one-month period were collapsed. Youths with any reported cannabis use received the score 0, whereas youths that reported no cannabis use during the 30-day period received a score of 1. This recoding was repeated for each month the youth participated in the study, providing up to five scores (months 0 to 4) of cannabis abstinence per youth. Similarly for the urine screen, youths with positive urine screens received a score of 0, and youths with negative screens received a score of 1, providing up to five scores of cannabis abstinence per youth (months 0 to 4).

In modelling cannabis abstinence as the dependent variable, a three-level logistic random intercept model was fitted, distinguishing between indicator (Level 1), occasion (Level 2), and family (Level 3). At Level 1, a fixed binomial variance of 3.29 was assumed ( ) (Snijders & Bosker, 1999). For occasion (Level 2) and family (Level 3), normally distributed random intercept variances were specified. A useful interpretation of this variance structure is to view the Level 1 variance as a measurement error component, and the Levels 2 and 3 as ‘true’ variance components of cannabis abstinence.

This study examined change at two levels of analysis that need to be distinguished. First, within treatment with each family (Level 2), therapist adherence might change as a natural function of treatment progress across the four-month period that MST is delivered to the family. Independent of within-therapy changes, therapist adherence might also change as a general diffusion of innovation. The latter would be indicated by an upward shift of the level of therapist adherence across therapies with different families (Level 3) delivered over a longer period, for this study a period of up to 12 months after the Quality Assurance Workshop. Since within- and between-therapy change operate on different time scales, it is essential that the analysis disentangle within-therapy and between-therapy change. We thus used a centered approach to time, by modeling therapist adherence as a function of within-therapy time (Level 2) and across-family time (Level 3). Since the intervention was delivered as a between-family factor Level 3), it is particularly the trend in intercepts across therapies that are of interest. This trend was estimated by modeling the between-family random intercept variance of therapist adherence as function of Level 3 predictors: study period (therapy onset before or after the workshop), group (IQA or WSO), and group by study period interaction, adjusting for within therapy time (Level 2). To achieve a meaningful interpretation of the intercept we centered within therapy-time (Level 2) to the midpoint of therapy with values ranging form −2 to 2. Time across families (Level 3) was centered at the time of workshop delivery, ranging from −6 to 11 months.

Results

Pre-Intervention Group Differences

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics on youth, family, and therapist characteristics. There was a higher proportion of boys in the IQA group (χ2(1) = 11.91, p < .0.001). The proportion of therapists with less than one year of experience with MST was higher in the IQA group (χ2(1) = 4.40, p < .05). For the other youth and therapist characteristics there were small and statistically non-significant differences between the groups.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Families and Therapists by Study Condition

| Intensive Quality Assurance | Workshop Only | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Characteristics (N = 41) | |||

| Sex Youth (n) | χ2= 11.91, <.001 | ||

| Male | 21 | 5 | |

| Female | 4 | 11 | |

| Family Income (n) | χ2= 0.87, ns | ||

| Less than USD 60,000 per year | 9 | 9 | |

| More than USD 60,000 per year | 13 | 7 | |

| Previous treatment | χ2= 0.58, ns | ||

| Yes | 8 | 7 | |

| No | 17 | 9 | |

| Therapist charachteristics (N = 21) | χ2= 0.15,ns | ||

| Sex therapist (n) | |||

| Male | 6 | 3 | |

| Female | 7 | 5 | |

| Education (n) | χ2= 3.22, ns | ||

| 2 year college degree | 5 | 6 | |

| College graduate | 7 | 2 | |

| More than College graduate | 1 | 0 | |

| Experience MST (n) | χ2= 4.40, p<.04 | ||

| Less than a year | 4 | 0 | |

| More than a year | 9 | 8 | |

Measurement Model of Therapist Adherence

Exploratory factor analysis on the CM-TAM revealed a two-factor structure for all informants, corresponding to the two-factor solution obtained in US validation studies (see appendix). To assess the cross-informant reliability, between-rater agreement was assessed through the intra-class correlation I (ICC1) for single informants and the intra-class correlation II for the mean of informants. The intra-class correlation for single informants was 0.57 for the monitoring score and 0.40 for the cognitive-behavioral score. The intra-class correlation for the mean of raters (ICC2) was 0.84 for the monitoring score and 0.73 for the cognitive-behavioral score.

Analysis of Selective Early Termination of Study Participation

Twenty-one out of 41 participants had available information on all five measurements. For the remaining 20 participants, therapy was successfully completed or was terminated before all five measurements were completed, which automatically initiated completion of study measurement since treatment adherence could no longer be assessed. There were no early dropouts from the study among families who remained in therapy. For one family, treatment was terminated after the first measurement, for three families, treatment was terminated after the second wave of measurement, for six after the third wave of measurement, and finally, for 10 families after the fourth measurement. To examine selective early termination we performed a discrete time survival analysis with time from the start of study participation to termination as the dependent variable using Mplus, with demographic factors and intervention group as time invariant covariates. There were no statistically significant differences in time to treatment termination across the two intervention groups or for demographic variables.

Analysis of Intervention Effects

Therapist Adherence

The main comparison was between the levels of therapist adherence before versus after the training intervention began. The hypothesis was that therapist adherence to CM procedures would increase in both training groups after the workshop, but that the increase would be more pronounced in the IQA condition. This expectation was evaluated by testing discontinuity of level and trend before and after onset of intervention.

Table 2 shows the sample mean level of therapist adherence across intervention groups, and that the level of therapist adherence was higher for therapies conducted after the workshop. For the CM component, the mean level of therapist adherence increased with 0.83 units for the IQA group and with 0.98 units for the WSO group. For the CBT component, the level of therapist adherence showed an increase of 0.75 units in the IQA group, corresponding to a difference in the range of 0.5–0.6 standard deviations. In the WSO group, the increase was 0.19 units, corresponding to a difference in the range of 0.1–0.2 standard deviations.

Table 2.

Multivariate Random Intercept Model of Intervention Effects on Contingency Management Therapist Adherence

| Monitoring | Cognitive-behavioral | Multivariate Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 95%CI | B | 95%CI | -2loglikelihood | |

| Block 1 | |||||

| Intercept | 1.42** | (0.11,2.72) | 2.27*** | (1.25,3.29) | 2 843.11 |

| Sex youth (0 = Male) | 0.44 | (−0.24,1.11) | −0.54** | (−1.06,−0.02) | |

| Sex therapist (0 = Male) | 1.00*** | (0.43,1.57) | −0.02 | (−0.47,0.42) | |

| Treatment history (0 = No previous treatment) | −0.07 | (−0.50,0.62) | 0.05 | (−0.48,0.38) | |

| Number of sessions (0 = 8 sessions) | 0.02 | (−0.01,0.04) | 0.03** | (0.01,0.05) | |

| Therapist experience | 0.06 | (−0.11,0.23) | 0.09 | (−0.041,0.22) | |

| Therapist education (0 = two years in college) | 0.61** | (0.06,1.15) | −0.23 | (−0.65,0.20) | |

| Month of therapy (0 = Month 3) | 0.22*** | (0.12,0.31) | 0.28*** | (0.19,0.37) | |

| Condition (0 = Workshop only) | 0.64 | (−0.45,1.73) | −0.31 | (−1.16,0.54) | |

| Block 2: Period | |||||

| Period (0 = before workshop) | 1.27** | (0.27,2.26) | −0.27 | (−1.05,0.51) | 2 835.76 |

| Block 3: Interaction | |||||

| Period by Condition | −0.58 | (−1.69,0.53) | 0.90** | (0.04,1.77) | 2 826.89 |

Note.

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

To formally test intervention effects, we assessed intercept differences between reports provided during the baseline period, and reports provided during the post-workshop period. Since therapist adherence consists of two components, a multivariate test was conducted, with separate regression coefficients estimated for the CM and the CBT component, but with an overall joint multivariate test of significance. Table 3 shows that, adjusting for confounding factors, there was a multivariate main effect of period, with overall fidelity increasing from before the workshop to after workshop (χ(2)= 7.36, p < .01). To test if there was a differential effect of period by condition, an interaction term was added to the model. Controlling for main effects, the multivariate period by treatment interaction was statistically significant (χ(2)= 8.86, p < .01), suggesting that the WSO group and the IQA group had different trends in therapist adherence from before workshop to after workshop. The adjusted coefficients for the CM component indicated that therapist adherence increased 1.27 units in the WSO group, and 0.68 in the IQA group. For the CBT component there was a slight decrease of 0.27 units in the WSO condition, but a strong increase in the IQA group of 0.63.

Table 3.

Logistic Random Intercept Model of Cannabis Abstinence Regressed on Therapist Adherence

| Separate CM component analysis | Combined CM component analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Monitoring | 4.35 | (1.70, 11.14) | 2.61 | (1.08, 6.31) |

| Cognitive Behavior | 4.95 | (1.86, 13.20) | 2.94 | (1.17, 7.40) |

| Adjusted for confoundersb | ||||

| Monitoring | 2.41 | (1.06, 5.49) | 2.14 | (0.92, 4.97) |

| Cognitive Behavior | 1.95 | (0.82, 4.63) | 1.45 | (0.62, 3.36) |

Estimates express odds of cannabis abstinence per unit increase in therapist adherence, before and after adjustment for putative confounders.

Sex of youth, sex of therapist, treatment history, number of sessions, therapist experience, therapist education and month of therapy were entered as confounders.

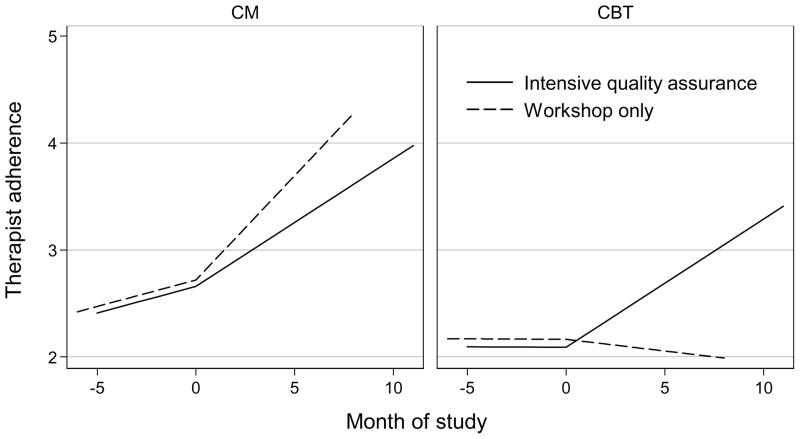

A targeted follow up analysis addressed temporal aspects of the trend. In this set of analyses, the two components of therapist adherence (i.e., both CM and CBT components) were simultaneously modeled as a function of month of the study, running from −6 months prior to 11 months post workshop. To accommodate the expected nonlinear trend a piecewise linear trend was specified. The first piece was from 6 months to the month preceding the workshop (pre-workshop), and the second piece was from the month succeeding the workshop to 11 months (post-workshop). The statistically significant group by post-workshop interaction (χ(2)= 13.18, p < .01) suggested that the post-workshop time effects were different for the two-conditions. Figure 1 shows the predicted values for the CM component and the CBT component, before and after the workshop. As shown in the figure, there was no significant difference in post-workshop trend for the CM component. For the CBT factor there was a strong positive difference in trend in favor of the IQA condition.

Figure 1.

Therapist adherence by study period and condition. The 5-point adherence values shown on the abscissa for each of the two components were: 1= Not at all, 2=A little, 3=Some, 4=Pretty Much, and 5=Very Much.

Cannabis Abstinence

The results from a multivariate two-level logistic random intercept model showed a statistically significant effect of time in therapy (B [95%CI] = 1.45 [0.69, 2.22]), but no trend related to the quality assurance intervention. The positive regression weight for time in therapy indicates that, independent of period or intervention group, the probability of negative drug screen increased markedly during therapy. In a follow up analysis, evaluation of whether this effect was due to selective early treatment termination was conducted, i.e., did those with positive drug screens during their participation in the study terminate treatment earlier compared to those without drug use? The analysis revealed no differences in slope or intercept between those who terminated treatment early and those who did not. Independent of treatment termination, there was a positive slope related to time in therapy.

Therapist Adherence and Cannabis Abstinence

A central assumption in the present study is that a high level of therapist adherence to CM/CBT increases the probability of positive treatment outcome. To examine the impact of therapist adherence to the components of CM/CBT, we regressed cannabis abstinence on therapist adherence in a logistic random intercept model, using therapist adherence as a time-varying covariate for cannabis abstinence. The analysis showed that increasing therapist adherence was associated with increasing cannabis abstinence.

Table 4 shows the odds ratio (OR) for cannabis abstinence for a unit increase in therapist adherence. To interpret what a unit increase in therapist adherence implies, it is helpful to consider the reported changes in therapist adherence, and the observed standard deviation of therapist adherence. A one-unit increase is less than a standard unit, and slightly more than the estimated intervention effect for the IQA group. The first column shows the OR when entering the CM and CBT components separately and the second column reports the OR when entering CM and CBT simultaneously in the model. The upper part of the table shows crude OR, while the lower part shows estimates adjusting for confounders.

When the two components were entered separately, a one-unit increase in the CM component predicted a more than 4:1 increased odds of cannabis abstinence, and a one- unit increase in the CBT component predicted an almost 5:1 increased odds of cannabis abstinence, although the confidence intervals were wide for both components. When entered simultaneously, both components were still uniquely related to cannabis abstinence. The lower part of the table shows that after adjusting for confounders, the OR decreased. When entered separately, an increase in CM predicted a 2.41 increased odds of cannabis abstinence. Although the OR was nearly 2:1, the CI for the CBT component was no longer statistically different from 1 when confounders were entered.

Discussion

The main purpose of the present study was to investigate whether an IQA intervention would enhance therapist adherence to CM/CBT. Therapist adherence to CM/CBT was higher during treatment delivered after a CM/CBT workshop, and the pattern of fidelity enhancement differed across the IQA and WSO conditions. For the CM component, both groups showed a linear increase after the Workshop. For the CBT component, the IQA group showed a significant improvement over successive time intervals, but the WSO group did not show change.

These results replicate and extend the findings of Henggeler et al. (2008). Similar to the results of that study, we found that only the CBT component was differentially enhanced by the IQA protocol. In the present study, the IQA group showed a consistent improvement over successive time intervals in the use of cognitive-behavioral techniques. In contrast with Henggeler et al. (2008), however, we found an increased adherence to the CM component over time, although the increase was not statistically different for the IQA and WSO groups. Henggeler and colleagues suggested that the lack of improvement on the monitoring component in their study might be a ceiling effect, because the monitoring adherence scores were relatively high even prior to the workshop. Thus, the increase in monitoring (i.e., CM) over successive time intervals found only in the Norwegian MST therapist population might reflect a relatively lower initial use of screening for substances and applying consequences for substance use among these therapists compared with the US therapists. The higher level of substance use screening among US therapists is probably related to the juvenile probation system which often mandates regular drug screening and is commonly involved with youths in MST in the US, often as the referral source. The increased use of such monitoring over time, even in the WSO condition, might have resulted from features of the study that served a quality assurance function even if not explicitly defined as such: First, as part of the monthly data collection procedure, therapists in both groups were asked specific questions regarding CM/CBT adherence, which strongly indicated the details of the fidelity that was expected of them. Second, the provision of drug screening equipment during the post-workshop period may, by itself, have encouraged their increased use.

When first integrating CM/CBT with MST, Henggeler et al. (2006) suggested that the CBT components (i.e., functional analysis and self-management planning interventions) were quite similar to cognitive-behavioral techniques already used as part of standard MST treatment, while the CM component (i.e., collection of random urine screens, use of vouchers) was more novel to the therapists. Yet, the implementation of CBT applied to the youth’s substance use was more dependent upon IQA procedures than was the implementation of CM procedures. Perhaps the learning of cognitive-behavioral techniques applied to substance use depends largely on interaction between therapist and the youth. That is, therapists may need “real world” practice using these techniques to become accustomed to implementing them and to learn how to overcome barriers that impede using the techniques (e.g., youth’s reluctance to share information with the family therapist about the context of youth’s drug use). Thus, such techniques may be more difficult to implement based on a single workshop – thereby improving the most when therapists receive weekly support in practicing them.

In comparing the present results with those obtained in the US study it is also relevant to note some analytical differences. First, the current study differed from Henggeler et al. (2008) in the way that reports from multiple informants were used. By including analysis from all informants, the present study used more information in the analysis. While informants’ perceptions of therapist adherence are likely to diverge, the shared variance of these reports likely reflects systematic information about the level of therapist adherence. In contrast, reports from any single informant likely include specific components, related to the informant’s mood, response style, knowledge, or role in the therapy session. The main benefit of using multiple informants was a gain in reliability, which was essential given the small sample size. Our judgement is that these gains outweigh the costs of losing information specific to the single informants. This study also differed in how change in therapist adherence was modeled. By centering time within and between therapies, the present study distinguished between change occurring at the group level and change occurring within each therapy. In the US study, time was modeled as a single fixed effect but individual differences in amount of change were included as a random effect.

The second research question was whether higher therapist adherence, regardless of condition, was associated with increased cannabis abstinence in the participating youth clients. The results indicated that stronger therapist adherence, in particular for the CM component, was associated with a higher probability of youth cannabis abstinence. However, because the degree of adherence to CM was not itself manipulated as an experimental independent variable, a functional relation between degree of CM adherence and youth cannabis abstinence cannot be determined. It is possible that it was easier for therapists to adhere to CM procedures when cases, for different reasons, went well with compliant youths.

Research has suggested that cannabis users might be less motivated to change their substance use than those who seek treatment for the abuse of other substances (Budney, Radonovich, Higgins, & Wong, 1997). Hence, treatment components that most directly target motivation for change, such as reinforcement contingent on cannabis abstinence, might be particularly potent for cannabis abusers (Budney & Stanger, 2008). The strong association between therapist adherence to the CM component and a lower probability of youth cannabis use also might reflect that CM is proximal to reinforcement of cannabis abstinence. In part, the CM component taps information about the therapists’ reinforcement contingent on clean screens and is, thus, relatively directly related to the target behavior.

Our third research question was whether quality assurance conditions would be associated with differential reductions in substance use of the youth clients. In the present study, there was a significant increase in cannabis abstinence for both groups of adolescents as a function of time in MST/CM/CBT therapy, but the magnitude of the increase was not different for the two groups. Hence, the IQA protocol did not improve the youth drug use results above and beyond those obtained by the WSO protocol. This lack of differential effects is consistent with the findings that therapist adherence to CM was the component that showed the more robust association with cannabis abstinence and this component showed no between-group differences. This apparently more robust short-term effect of CM than of CBT is also consistent with the results of a number of previous studies that have shown that although CBT seems to serve an important function of maintaining abstinence following the termination of CM treatment (Budney, Moore, Rocha, & Higgins, 2006; Kadden, Litt, Kabela-Cormier, & Petry, 2007), CM has been found superior to CBT for promoting marijuana abstinence during treatment (Budney, Higgins, Radonovich, & Novy, 2000,Budney, Higgins, Radonovich, & Novy, 2006) and at posttreatment (Kadden et al., 2007).

Finally, a number of limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the number of participating families, as well as the number of therapists that actually worked with families with substance-abusing youths during the study period, was lower than expected based upon rates of substance use in youths participating in previous MST studies. This indicates that the statistical power was lower than originally planned for. Second, regarding our combining of informant ratings of therapist fidelity, it could be argued that for some specific behaviors, one or the other informant would be better informed and that others might even not have any direct knowledge. However, when using a composite score we demonstrated a high level of common variance between informants, suggesting a high degree of shared information. Third, it is possible that some of the potential differences between the IQA and the WSO conditions were washed out by the monthly completion of fidelity interviews with therapists in both groups. As suggested previously, the very detailed questions regarding CM/CBT fidelity may have served as a non-intended quality assurance variable by repeatedly specifying details of the fidelity that was expected of them. Therefore, a future study should include the distribution of the CM-TAM to the therapists as an experimental variable.

In sum, the present study replicated and extended the findings of a US study (Henggeler et al., 2008) with a Norwegian population of MST therapists and families of youth with cannabis use problems. The results showed (1) that a specific intensive quality assurance system enhanced therapist adherence over workshop for cognitive-behavioral techniques, (2) stronger therapist adherence to CM was associated with a higher probability of cannabis abstinence in the youths, and (3) that the intensive quality assurance system did not differentially enhance therapist CM skills over the workshop only condition. For Norwegian therapists, CM skills improved over time for therapists, irrespective of condition, suggesting that the CM workshop followed by clinical practice and monthly reminders through assessment may suffice to establish those skills.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by grants K23DA015658 and R01DA015844 (International Supplement) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NIH.

We sincerely thank the clinical and research staffs for their participation and collaboration.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Exploratory factor analysis of the TAM-CM questionnaire

| Supervisor | Therapist | Youth | Caregiver | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 |

| The therapist gave negative consequences (punishments) to my child if the drug screen was dirty and positive consequence | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.94 | - | 0.84 | - |

| The therapist made sure I gave a positive or negative consequence for my child’s drug screen results. | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.86 | - | 0.79 | - |

| My family was informed of my child’s drug test results within 24 hours | 0.98 | - | 0.84 | - | 0.58 | −0.11 | 0.54 | - |

| The therapist tested my child for alcohol or drug use by breathalyzer or drug screen. | 0.88 | - | 0.90 | - | 0.50 | - | 0.45 | −0.12 |

| The therapist helped my child think of ways to tell people that he/she does not want to use drugs | - | 0.89 | - | 0.67 | - | 0.54 | - | 0.77 |

| The therapist helped my child practice what to do when things or triggers happen that might cause him/her to use drugs | - | 0.94 | - | 0.71 | 0.12 | 0.74 | - | 0.78 |

| The therapist helped my child make a list of things or triggers that might cause him/her to use drugs or alcohol. | - | 0.80 | - | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.59 |

| The therapist helped my child practice how to act if someone offers him/her drugs, that is, ways to refuse drugs. | - | 0.97 | - | 0.92 | - | 0.95 | - | 0.98 |

| The therapist helped my child come up with ways to get out of situations that involve drug use | - | 0.95 | - | 0.94 | - | 0.93 | - | 0.94 |

References

- Andrzejewski ME, Kirby KC, Morral AR, Iguchi MY. Technology transfer through performance management: the effects of graphical feedback and positive reinforcement on drug treatment counselors’ behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Levitt JT, Bufka LF. The dissemination of empirically supported treatments: a view to the future. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Ogden T. The evolution of evidence-based practices. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2008;9:81–95. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2008.11434297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST. A community reinforcement plus vouchers approach: Treating cocaine addiction (No. No. 98-4309) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Radonovich KJ, Novy PL. Adding voucher-based incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1051–1061. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, Higgins ST. Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:307–316. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.4.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Radonovich KJ, Higgins ST, Wong CJ. Adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence: A comparison with cocaine-dependent treatment seekers. Paper presented at the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College-on-Problems-of-Drug-Dependence; Nashville, Tennessee. 1997. Jun 16–17, [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Stanger C. Marijuana. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. The Oregon Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care model: Features, outcomes, and progress in dissemination. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10:303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JE, Sheidow AJ, Henggeler SW, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB. Developing a measure of therapist adherence to contingency management: An application of the many-facet Rasch model. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:47–68. doi: 10.1080/15470650802071655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham PB, Donohue B, Randall J, Swenson CC, Rowland MD, Henggeler SW, et al. Integrating contingency management into multisystemic therapy. Charleston, SC: Medical University of South Carolina; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue B, Azrin NH. Family behavior therapy. In: Wagner EF, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse. New York: Pergamon Press; 2001. pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. (FMHI Publication #231) [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Randall J, Shapiro SB, Chapman JE. Juvenile Drug Court: Enhancing Outcomes by Integrating Evidence-Based Treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:42–54. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: An effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Serious emotional disturbance in children and adolescents: Multisystemic therapy. New York: Gulford press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ, Cunningham PB, Donohue BC, Ford JD. Promoting the implementation of an evidence-based intervention for adolescent marijuana abuse in community settings: Testing the use of intensive quality assurance. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:682–689. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ, Lee T. Multisystemic treatment of serious clinical problems in youths and their families. In: Roberts AR, Springer DW, editors. Handbook of forensic mental health with victims and offenders: Assessment, treatment, and research. New York: Springer Publishing; 2007. pp. 315–345. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Lussier JP. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance abuse disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden RM, Litt MD, Kabela-Cormier E, Petry NM. Abstinence rates following behavioral treatments for marijuana dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1220–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:19–36. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Somlai AM, DiFranceisco WJ, Otto-Salaj LL, McAuliffe TL, Hackl KL, et al. Bridging the gap between the science and service of HIV prevention: Transferring effective research-based HIV prevention interventions to community AIDS service providers. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1082–1088. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SF, Irwin K. Blueprints for violence prevention: From research to real-world settings – factors influencing the successful replication of model programs. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2003;1:307–329. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Form 90: Structured Assessment for Drinking Related Behavior. Wasington DC: NIAAA; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden T, Christensen B, Sheidow AJ, Holth P. Bridging the gap between science and practice: The effective nationwide transport of MST programs in Norway. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden T, Halliday-Boykins CA. Multisystemic Treatment of Antisocial Adolescents in Norway: Replication of Clinical Outcomes Outside of the US. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2004;9:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2004.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Hill PL, O’Brien R, Racine D, Moritz P. Taking preventive intervention to scale: The nurse-family partnership. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 2003;10:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in clinical settings. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall J, Henggeler SW, Cunningham PB, Rowland MD, Swenson CC. Adapting multisystemic therapy to treat adolescent substance abuse more effectively. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 2001;8:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK. Toward evidence-based transport of evidence-based treatments: MST as an example. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, Henggeler SW. Multisystemic therapy for alcohol and other drug abuse in delinquent adolescents. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2008;26:125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strtegies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K. Exploring the Limits and Utility of Operant Conditioning in the Treatment of Drug Addiction. The Behavior Analyst. 2004;27:209–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03393181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Robles E, Mudric T, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. A randomized trial of long-term reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in methadone-maintained patients who inject drugs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:839–854. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strother KB, Swenson ME, Schoenwald SK. Multisystemic therapy organizational manual. Charleston: MST Services; 1998. [Google Scholar]