Abstract

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a premalignant condition strongly associated with the practice of chewing areca nut, a habit common among South Asian population. It is characterised by inflammation, increased deposition of submucosal collagen and formation of fibrotic bands in the oral and paraoral tissues, which increasingly limit mouth opening. A case of OSMF occurring in a 9-year-old Indian girl is presented. This paper discusses the aetiology, clinical presentation and treatment modalities of oral submucous fibrosis.

Background

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) was described three decades earlier by Pindborg and Sirsat1 as a chronic insidious disease affecting any part of the oral cavity and may extend to the pharynx and the oesophagus, and may be preceded by or associated with vesicle formation. It is always associated with juxta-epithelial inflammation and followed by fibro-elastic change of the lamina propria with epithelial atrophy leading to stiffness of the oral mucosa, causing trismus and inability to eat.2 OSMF is seen most frequently in communities resident in the Indian sub continent and has a reported incidence between 0.2% and 1.2% of the urban population attending dental clinics.3 The condition characteristically first presents in adulthood between the ages of 45–54 years.3 The present report describes a case of OSMF presenting in a young Indian child of 9 years.

Case presentation

A girl aged 9 years reported to the department of paedodontics, Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore with the complaint of inability to open the mouth since 4 years, burning sensation of buccal mucosa while taking spicy food since 3 years with no other systemic or dermatologic problem. Patient was first seen in February 2009 and her most recent review was in October 2009. The patient reported with a habit of chewing areca nut (sweet supari) 3–4 times a day for past 5–6 years. A long standing history of chewing areca nut was present in both the parents and younger sister. Examination revealed that her mouth opening was limited to about 16 mm (figure 1). Intraoral examination revealed entirely blanched oral mucosa (figure 2). The tongue movements were restricted. Vertically thick fibrotic bands were palpable bilaterally on the buccal mucosa, retromolar area, hard and soft palate. General examination was normal.

Figure 1.

Pretreatment limited mouth opening.

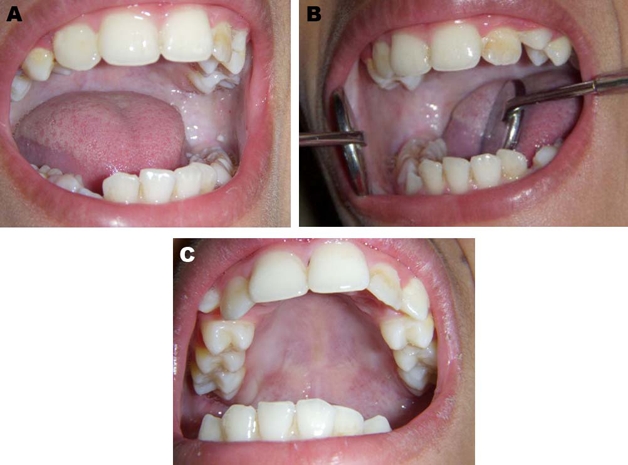

Figure 2.

(A) Blanched oral mucosa right side. (B) Blanched oral mucosa left side. (C) Blanched hard palate mucosa.

Investigations

An incisional biopsy from buccal mucosa showed thick parakeratinised proliferative stratified squamous epithelium, dense fibrous connective tissue stroma with chronic inflammatory infilterate. A diagnosis of OSMF in a moderately advanced stage was made based on the characteristic oral findings as generalised blanching of mucosa, extensive fibrosis and limited mouth opening.

Treatment

The patient was advised to stop chewing areca nut. She was treated with intralesional injections of placental extract 2 ml (placentrax) alone, combination of steroid dexamethasone 4 mg (dexona) and hyaluronidase 1 ml (hylase) weekly for 8 weeks. The injections were given at multiple sites at places of palpable thick bands, separately with gap of 3 days. Patient was advised mouth opening exercises by ice-cream sticks.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient was kept under follow-up. She has stopped chewing areca nut and showed improvement in symptoms and mouth opening increased by 4 mm. Patient’s mucosal blanching was reduced with improvement in symptoms (figure 3).

Figure 3.

After 2 months of injection therapy.

Discussion

OSMF is a high risk precancerous condition that predominantly occurs among South Asian population. This condition was first reported in India in 1953.4 The aetiology of OSMF remains uncertain and at the present time there is evidence to suggest that a combination of factors are likely to be involved. In the literature a number of factors that include chilli consumption, areca nut chewing, autoimmunity, nutritional factor and genetic predisposition (human leukocyte antigen-A 10, DR 3, DR 7 and halotypes A 10/DR 3, B 3/DR 3 and A 10/B 8) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of submucous fibrosis.5–7

Now there is convincing epidemiologic evidence implicating areca nut as a causative factor in the pathogenesis of this condition. Areca nut is traditionally chewed throughout India as ‘paan supari’.5 The mixture is held adjacent to the buccal mucosa and slowly chewed over a long period of time. Tissue culture studies using human fibroblasts by Harvey et al. suggests that areca nut alkaloids, particularly arecoline and arecaidine, were involved in causing OSMF.8 Furthermore it was demonstrated that extracts of areca-nut stimulate collagen synthesis by 170% over the control studies.8 More recently the chewing of gutkha; a sweetened mixture of tobacco and betel-nut, has increased in this country and its use is thought to be commercially aimed at children.9

There would appear to be a predisposition in females with a ratio of women to men of 3:1.10 Occurrence of OSMF in children is rare. Though cases between ages of 4–15 years have been reported.11 12 Our case is of severe OSMF in a 9-year-old girl who started chewing areca nut at an age of 3 years.

Diagnosis of OSMF is usually based on the clinical signs and symptoms, which include; oral ulceration, burning sensation (particularly with spicy foods), paleness of the oral mucosa and occasional leukoplakia. The most characteristic feature is the marked vertical fibrous bands formation within the cheeks, and board like stiffness of the buccal mucosa. The fibrosis in the soft tissue leads to trismus, difficulty in eating and even dysphagia.11 12

The association of the condition with the chances of development of oral cancer highlights the importance of education to limit OSMF. The possible precancerous nature of OSMF was first described by Paymaster, who observed the occurrence of squamous cell carcinoma in one third of his patients with OSMF.13 Subsequent studies have reported that the incidence of carcinoma varies in OSMF from 2% to 30%.14

At the present time, there is no cure for OSMF and management consists of elimination of the ingestion of implicated irritants. Successful prevention in the early stages of the condition has been shown to produce improvement in symptoms. Medical and surgical management are emperical and unsatisfactory. Various agents such as steroids (dexamethasone), hyaluronic acid (hyalase), placental extract (placentrax), interferons have been used alone or in combination as intralesional injections weekly for 6–8weeks. They act by different mechanisms, anti-inflammatory action (steroid), dissolving connective tissue (hylase), biogenic stimulation (placental extract), immunomodulation (interferons). Surgical care is indicated in patients with severe trismus, dysplasia or neoplasia. Surgical modalities include simple excision of fibrous bands, skin grafting to use of nasolabial pedicle flaps.

In our case, the patient responded to initial treatment. She has stopped chewing areca nut. Placental extract was used alone. Combination of steroid with hyaluronidase was used which shows better results than when used seperately.15 Mouth opening has increased by 4 mm, there is no burning sensation in buccal mucosa on eating food. Patient will have to be kept in follow-up to monitor progression of disease even after therapy.

If the condition of this patient worsens, she may in the long-term need surgical intervention with grafting, there is always the possibility of malignant change, and therefore close monitoring of her oral mucosa is essential.

Learning points.

-

▶

Paedodontist should be aware of OSMF occurring at such a young age so that early diagnosis, counselling and proper management can be done to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.

-

▶

No definitive and widely accepted treatment is currently available for this condition. Medical treatment has a role in management of sub mucous fibrosis with good follow-up.

-

▶

In view of the lack of availability of curative treatment, and the precancerous nature of this disease, it is essential to follow-up the patients regularly.

-

▶

Patients must be educated to discontinue the use of areca nut and tobacco in any form, with the aim of preventing further progress of the disease and perhaps reducing the risk of oral cancer. Encouragingly, submucous fibrosis is amenable to primary prevention.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966;22:764–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shwartz J. Atrophica idiopathica (tropica) mucosea oris. Demonstrated at the eleventh International Dental congress, 1952, London [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayanthi V, Probert CS, Sher KS, et al. Oral submucosal fibrosis–a preventable disease. Gut 1992;33:4–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joshi SC. Submucous fibrosis of the palate and pillars. Indian J Otolaryngol 1953;4:1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Gupta PC, et al. Etiology of oral submucous fibrosis with special reference to the role of areca nut chewing. J Oral Pathol Med 1995;24:145–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirsat SM, Khanolkar VR. Submucous fibrosis of the palate in diet-preconditioned Wistar rats. Induction by local painting of capsaicin–an optical and electron microscopic study. Arch Pathol 1960;70:171–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canniff JP, Batchelor JR, Dodi IA, et al. HLA-typing in oral submucous fibrosis. Tissue Antigens 1985;26:138–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey W, Scutt A, Meghji S, et al. Stimulation of human buccal mucosa fibroblasts in vitro by betel-nut alkaloids. Arch Oral Biol 1986;31:45–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedi R. What is gutkha? BDA News 1999;12:20–1 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canniff JP, Harvey W, Harris M. Oral submucous fibrosis: its pathogenesis and management. Br Dent J 1986;160:429–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes PA. Oral submucous fibrosis in a 4-year-old girl. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985;59:475–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah B, Lewis MA, Bedi R. Oral submucous fibrosis in a 11-year-old Bangladeshi girl in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 2001;191:130–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paymaster JC. Cancer of the buccal mucosa; a clinical study of 650 cases in Indian patients. Cancer 1956;9:431–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGurk M, Craig GT. Oral submucous fibrosis: two cases of malignant transformation in Asian immigrants to the United Kingdom. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984;22:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakar PK, Puri RK, Venkatachalam VP. Oral submucous fibrosis–treatment with hyalase. J Laryngol Otol 1985;99:57–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]