SUMMARY

Granular cell tumour is a rare soft tissue neoplasm that can virtually affect any site of the body. Its histological origin is controversial, since several studies have shown that different cells are involved. Granular cell tumour was initially described as myoblastoma, but, at present, a neural origin is supported by most Authors, due to the immunohistochemical pattern. Even if the biological behaviour of granular cell tumours is usually benign, accurate histological examination is mandatory, because in a small number of cases they can be malignant. Here, a case is described of granular cell tumour in a 14-year-old boy, which is a very rare occurrence, since these tumours typically manifest in subjects between the third and sixth decade. Histopathological features, differential diagnosis and therapeutic implications of granular cell tumour are discussed, together with a brief review of the recent literature.

KEY WORDS: Tongue, Granular cell tumour, Abrikossoff, Myoblastoma

RIASSUNTO

Il tumore a cellule granulari (TCG) è una rara neoplasia dei tessuti molli che può interessare ogni sede corporea. La sua istogenesi è ancora controversa; diversi studi hanno infatti dimostrato il coinvolgimento di differenti linee cellulari. Esso è stato inizialmente definito "mioblastoma", ma attualmente molti Autori fanno riferimento ad una probabile origine neurale, sulla base del quadro immunoistochimico. I tumori a cellule granulari sono di natura prevalentemente benigna, ma è sempre necessario eseguire un accurato esame istologico, perché, seppur solo in rari casi, essi possono manifestare caratteri di malignità. In questo lavoro presentiamo un caso di tumori a cellule granulari insorto in un paziente di soli 14 anni, evenienza assai rara, considerato che questi tumori si manifestano tipicamente tra la terza e la sesta decade di vita. Vengono descritti l'aspetto istopatologico, la diagnosi differenziale ed il trattamento della lesione insieme ad una breve revisione della letteratura recente.

Introduction

Granular cell tumour (GCT), or Abrikossoff's tumour, first described, in 1926, by the Russian pathologist Alexei Ivanovich Abrikossoff, represents a rare entity, with a reported prevalence ranging from 0.019% to 0.03% of all human neoplasms 1. It can affect soft tissues virtually in any body site, and typically manifests in adults between the third and the sixth decade, usually showing a benign behaviour; women are affected twice as much as men (M/F ratio = 1:2) 2. The histological origin of GCT is controversial, since different derivations have been postulated by various Authors, including fibroblasts 3, myoblasts 4, undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, Schwann cells 5, histiocytes 6 and neural cells 7. Accordingly, different definitions have been applied to this entity, such as myoblastoma, granular cell neurofibroma, and granular cell schwannoma.

The neuroectodermal origin is now generally accepted due to the reactivity of GCT for neural markers 8, although recent investigations 9, considering large series, demonstrated that the tumour could be regarded as the expression of local metabolic or reactive changes, rather than as a true neoplasm; this is demonstrated by the wide variety of features and architectural patterns, as well as by the usually benign behaviour of GCT. Albeit, in these recent studies, immunohistochemical reactivity of granular cells to broad panels, including antibodies directed against different tissues, did not confirm any particular differentiation.

It has been demonstrated that GCTs of the oral cavity can occur both in paediatric and advanced age, but their incidence usually peaks between the fourth and the sixth decade 10, while their occurrence before the age of 20 years is very rare 2.

GCT frequently appears as a solitary tumour, but multifocal lesions have also been described 11. Despite the fact that most of these lesions arise in the cervico-facial region (up to 50% of GCTs occur in the head and neck 12), only a few cases have been reported in the oral cavity 13.

Case report

A 14-year-old boy came to our attention with a painless lingual swelling, incidentally discovered three months earlier. He did not complain of bleeding, and no significant clinical data (diabetes, hypertension, allergies) were present in his clinical history; our patient had always been well and he referred to a healthy lifestyle; laboratory investigations were substantially normal. Physical examination confirmed the presence of a primarily right-seated mass involving the apex and body of the tongue, and the patient underwent surgical excision of the tumour, followed by pathological examinations.

The surgical specimen measured 17 × 15 × 4 mm with a depressed and peripherally ulcerated area about 10 mm in maximum length; on the cut surface, the ulceration appeared as a vaguely nodular grey-to-red lesion, with ill-defined borders. On histological examination, the lingual epithelium showed marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, while in the underlying submucosa a neoplastic proliferation was observed. Neoplastic cells were mainly round, with small hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, strictly intermingled with bundles of striated muscle and fibrous tissue, and disposed in nests and sheets of variable size; the tumour showed infiltrative and ill-defined borders. Intra-cytoplasmic PAS-positive granules were revealed by the appropriate histochemical staining. At immunohistochemistry, all neoplastic cells were S-100-positive and CD68(PGM1)-positive. The proliferation index, semiquantitatively evaluated with Ki67 (clone K2)-labelling index, was very low, very close to 0%. Surgical margins were negative.

In conclusion, all histomorphological and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with GCT of the tongue. The patient was first examined one week later and then, respectively, 1, 4, 7, 14 and 20 months after the surgical excision; so far, no sign of recurrence has been noted. Albeit, further close follow-up has been planned to assess the effectiveness of the eradication and to prevent any possible relapse of the disease.

Discussion

GCTs are unusual in the first and second decade, therefore, in children and adolescents, many other benign lesions should be considered in the differential diagnosis: amongst which, minor salivary gland tumours, dermoid cysts, vascular lesions, lipomas, benign mesenchymal neoplasm, neurofibroma and traumatic fibroma 14. Moreover, GCT often presents as uncapsulated, often as a pseudo-invasive lesion 15, therefore, even several malignancies, such as squamous carcinoma and malignant melanoma, should be ruled out, even if they rarely arise in the oral cavity of young patients. Moreover, in the overlying lingual epithelium various degrees of pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia are frequently seen, and this can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1); therefore, if incisional biopsy is performed, it should be deep enough to include underlying infiltrating granular cells 12.

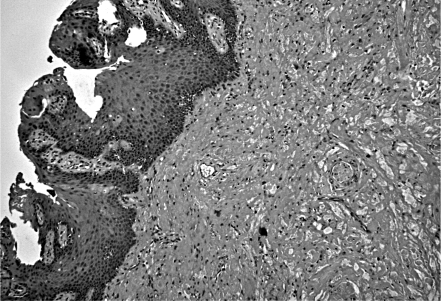

Fig. 1.

Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium (left) underlying the tumour (right) is a frequent feature associated with GCT; hence, squamous cell carcinoma should be ruled out in the differential diagnosis (H&E, original magnification: 100).

Surgical excisional biopsy of the tumour represents the first choice, both for diagnosis and treatment and, in the majority of cases, it is curative; albeit, removal of the lesion should be wide enough to grant oncological radicality, irrespective of the final histological diagnosis. Upon histological examination, GCT typically shows small nests and sheets of polygonal cells with small vesicular nuclei and granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 2); the latter is due to intracytoplasmic accumulation of lysosomes and appears to be the main morphological feature of GCTs, better seen in PAS-stained slides 16. Another peculiar finding is S100- reactivity, that suggests a neural origin of the tumour; it should be remembered that granular cell populations have been described in some non-neural neoplasms of the skin, including benign fibrous histiocytoma, dermatomyofibroma and cutaneous leiomyosarcoma; albeit, these tumours are S100-negative, in contrast to the classic GCT 17.

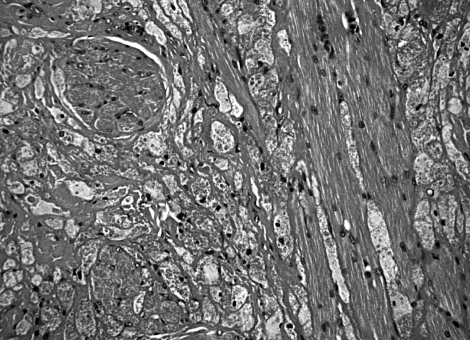

Fig. 2.

Irregular nests and sheets of neoplastic cells were strictly intermingled with bundles of striated muscle and fibrous tissue (H&E, original magnification: 200).

Another rare and recently described entity, sharing common histological features with GCT, is congenital granular cell lesion (CGCL), also known as congenital granular cell epulis or congenital granular cell tumour. Based on a recent review, only 7 cases of CGCL of the tongue were reported in the literature; moreover, differential diagnosis between GCT and CGCL can be made by immunochemical staining for S-100, that is negative in CGCL and positive in GCT 18.

The potential aggressiveness of this tumour should never be overlooked, given the fact that 1-3% of GCTs can present in a malignant way 19. According to an accurate AFIP study, histological malignancy should be suggested by the presence of 3 or more of the following 6 criteria: 1) high mitotic activity (> 2 mitoses/10 fields at 200× magnification); 2) necrosis; 3) high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio; 4) spindling; 5) vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli; and 6) pleomorphism. Neoplasms featuring only one or two of the above-mentioned should be diagnosed as "atypical" GCT 20. Moreover, accurate histological examination should include the assessment of proliferation markers, with particular regard to the Ki67-labelling index; nuclear antigen Ki67 is expressed during every phase of the cell cycle except G0 and, therefore, it can represent an important predictive factor 21. In malignant GCTs, the Ki67-index is usually > 10% 20. In our case, the presence of hyperchromatic, but typical nuclei, abundant cytoplasm, lack of mitotic figures, and very low Ki67-index (close to 0%) ruled out an aggressive behaviour and the lesion was hence diagnosed as benign GCT (Fig. 3). It should be emphasized that a definitive diagnosis of GCT can only be made following accurate histological examination, and that the risk of recurrence is strongly influenced by the status of the surgical margins 19 22, which, in our case, were tumour-free. After surgery, long-term follow-up should be started, because of the risk of local or distant recurrence even several years after surgery 12. The recurrence rate is very variable, ranging from 2-50%, depending on surgical radicality and on the presence of infiltrative growth pattern 23.

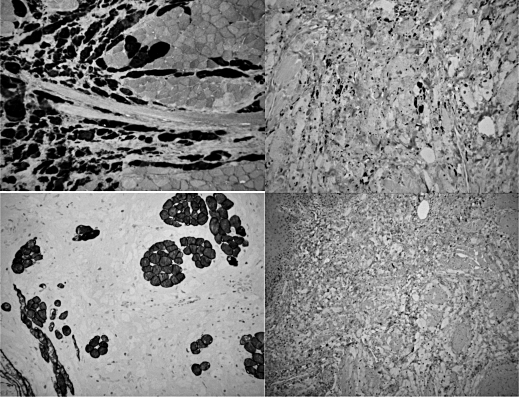

Fig. 3.

On immunohistochemistry, tumour cells were positive for pS100 (a) and CD68/PGM1 (b). Staining for desmin (c) confirmed the presence of bundles of striated muscle entrapped between neoplastic cells. The Ki67- index was very low, close to 0% (d). All pictures were originally taken at 200 magnification.

Conclusions

Despite its low prevalence, GCT should be considered in the differential diagnosis of oral lesions, particularly when they are located in the tongue. Differential diagnosis between GCT and several other benign and malignant neoplasms, eventually showing granular cell features, such as smooth muscle, vascular, fibrohistiocytic, true histiocytic, and melanocytic tumours, is extremely important with regard to treatment and prognosis 20. In this setting, complete surgical removal of the tumour must be attempted, given the possibility of GCT to recur, and histological examination is the only way to assess the biological behaviour. Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry can confirm the diagnosis of GCT when S100-positive cells containing PAS-positive and CD68-reactive granules are seen 1 24. Adverse immunohistochemical prognostic factors of GCTs include Ki67-index > 10% and p53 immunoreactivity 20. In the present case, we did not find any histological criterion of malignancy, and, not unlike the findings of Chrysomali et al. 21, the Ki67- index was very low, resulting positive only in occasional cells. Albeit, several cases of local and distant recurrence, even many years after excision of the primary tumour, have been reported in the literature, hence these lesions require long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, we suggest that every oral lesion of unknown nature should undergo physical examination and/ or appropriate imaging to reveal the clinical extension of the disease, and then, when feasible, surgically removed. The excision should be wide enough to ensure oncological radicality and accurate histological examination of the specimen; when granular cells are seen on histology, an appropriate immunohistochemical panel should be applied in order to assess the histological derivation and proliferative index of the tumour. Further clinical management can vary depending on the final histological diagnosis: when GCT is diagnosed, close follow-up should be planned in order to prevent any relapse. Anyway, morphological criteria and the Ki67-index can offer important prognostic information which allows the clinician to predict the biological behaviour and the risk of recurrence and to avoid emotional discomfort to the patient, when no histological criteria of malignancy are observed and the proliferative index is low (Ki67-index <10%).

References

- 1.Ayadi L, Khabir A, Fakhfakh I, et al. Granular cell tumor. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2008;109:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.stomax.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohamad Zaini Z, Farah CS. Oral granular cell tumor of the lip in an adult patient. Oral Oncol EXTRA. 2006;2:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearse AGE. The histogenesis of granular cell myoblastoma (granular cell perineural fibroblastoma) J Pathol Bacteriol. 1950;62:351–362. doi: 10.1002/path.1700620306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray MR. Cultural characteristics of three granular cell myoblastomas. Cancer. 1951;5:857–867. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195107)4:4<857::aid-cncr2820040423>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher ER, Wechsler H. Granular cell myoblastoma as misnomer. EM and histochemical evidence concerning its Schwann cell derivation and nature (granular cell schwannoma) Cancer. 1962;15:936–936. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196209/10)15:5<936::aid-cncr2820150509>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eversole LR, Sabes WR. Granular sheath cell lesions: report of cases. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:867–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zangari F, Trombelli L, Calura G. Granular cell myoblastoma. Review of the literature and report of a case. Minerva Stomatol. 1996;45:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arevalo C, Maly B, Eliashar R, et al. Laryngeal granular cell tumor. J Voice. 2008;22:339–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vered M, Carpenter WM, Buchner A. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity: update immunohistochemical profile. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sierra M, Sebag F, Micco C, et al. Tumeur d'Abrikossoff de l'oesophage cervical: une cause rare de faux nodule thyroïdien. Ann Chir. 2006;131:219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.anchir.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sargenti-Neto S, Braz�o-Silva MT, Nascimento Souza KC, et al. Multicentric granular cell tumor: report of a patient with oral and cutaneous lesions. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leboulanger N, Rouillon I, Papon JF, et al. Childhood granular cell tumors: two case reports. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura K, Sekiya W, Yamada R, et al. A case of granular cell tumor that developed (originated) in the tongue, Poster 092 AAOMS. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(9s1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagaraj PB, Ongole R, Bhujanga-Rao BR. Granular cell tumor of the tongue in a 6-year-old girl - a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E162–E164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giuliani M, Lajolo C, Pagnoni M, et al. Tumore a cellule granulari della lingua (tumore di Abrikossoff). Presentazione di un caso clinico e revisione della letteratura. Minerva Stomatol. 2004;53:465–465. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ordonez NG. Granular cell tumor: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol. 1999;6:186–203. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacroix-Triki M, Rochaix P, Marques B, et al. Granular cell tumors of the skin of non-neural origin: report of 8 cases. Ann Pathol. 1999;19:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senoo H, Iida S, Kishino M, et al. Solitary congenital granular cell lesion of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:e45–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junquera LM, Vincente JC, Vega JA, et al. Granular-cell tumours: an immunohistochemical study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(97)90560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, et al. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779–794. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chrysomali E, Nikitakis NG, Tosios K, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of cell proliferation antigen Ki-67 and apoptosis-related proteins Bcl-2 and caspase-3 in oral granular cell tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2003;96:566–571. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(03)00371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becelli R, Perugini M, Gasparini G, et al. Abrikossoff's tumor. J Craniofacial Surg. 2001;12:78–81. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidwell RU, Rouse P, Owen RA, et al. Granular cell tumor of the scrotum in a child with Noonan syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:341–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An JS, Han SH, Hwang SB, et al. Granular cell tumors of the abdominal wall. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:727–730. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.4.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]