SUMMARY

In a muscle biopsy based study, only 9 out of 5450 biopsy samples, received from all parts of greater Istanbul area, had typical clinical and most suggestive light microscopic sporadic-inclusion body myositis (s-IBM) findings. Two other patients with and ten further patients without characteristic light microscopic findings had referring diagnosis of s-IBM. As the general and the ageadjusted populations of Istanbul in 2010 were 13.255.685 and 2.347.300 respectively, the calculated corresponding ‘estimated prevalences' of most suggestive s-IBM in the Istanbul area were 0.679 X 10-6 and 3.834 X 10-6. Since Istanbul receives heavy migration from all regions of Turkey and ours is the only muscle pathology laboratory in Istanbul, projection of these figures to the Turkish population was considered to be reasonable and an estimate of the prevalence of s-IBM in Turkey was obtained.

The calculated ‘estimated prevalence' of s-IBM in Turkey is lower than the previously reported rates from other countries. The wide variation in the prevalence rates of s-IBM may reflect different genetic, immunogenetic or environmental factors in different populations.

KEY WORDS: Sporadic inclusion body myositis, s-IBM, prevalence, myopathy

Introduction

Although s-IBM is recognized as the most prevalent acquired myopathy in patients over age 50 years (1-3), population studies reporting the incidence or prevalence rates are very few. Population studies in Caucasian populations of North America, Northern Europe and Western Australia show high general and age-adjusted prevalence rates (3-7). Furthermore, it is strongly affirmed by some authors that the condition is underdiagnosed (2, 3, 7, 8). On the other hand, observation that s-IBM is rare in Israel and Sicily (Italy) has been reported as personal communication (2, 3). As we had a similar observation in our population and also as the Neuromuscular Pathology Laboratory of Istanbul University is the only adequate neuromuscular pathology laboratory in Istanbul receiving muscle and nerve biopsies from all parts of greater Istanbul, with an average of 400-450 muscle biopsies annually, we aimed at calculating the ‘estimated prevalence’ of s- IBM in Istanbul/Turkey.

Materials and methods

All muscle biopsies were reviewed by the same author (P.SO) who had been trained to search for s-IBM. Fifty percent of the muscle biopsies were from the Neuromuscular Clinic and 10% were from the Rheumatology and Pediatric Neurology Clinics of Istanbul University. A further 40% of the biopsies was sent by different hospitals from all parts of Istanbul. The study is based on muscle biopsies which had been received by the Neuromuscular Pathology Laboratory between 1993 (the main establishment of the laboratory) and 2011.The corresponding biopsy request forms were the used as the source of the clinical information of the patients. A total of 5450 muscle biopsies, 673 from individuals at or over age 50 years were considered. In order to include the possible uncommon presentations, biopsies belonging to individuals with clinical onset at or over age 30 years were selected among this group. Thus, 533 biopsies and their available clinical data were included in the study.

As Amyloid β, SMI-31 and MHC-1 immunocytochemistry were not available in the former years, these parameters were not considered in the classification of the cases. Electron microscopy is still not performed routinely. In the absece of amyloid β or SMI-31 immunocytochemistry and electron microscopic study, the recognized diagnostic criteria were not used and the term ‘most suggestive’ instead of ‘definite’ was used to describe s-IBM pathology (9). In order to prevent under- estimation, patients with typical symptoms/signs but only suggestive light microscopic findings, and the ones with biopsies without inflammation and vacuoles but with clinical working diagnoses of s-IBM were also considered. Typical symptoms/signs were defined as longstanding distal weakness or quadriceps femoris muscle involvement.

The patients were grouped in the following order:

Group A) Most suggestive s-IBM

Specimen: Light microscopic s-IBM (endomysial inflammation + intracellular red-rimmed vacuoles + considerable COX(-) fibers)

Request form: Typical symptoms/signs of s-IBM,

Group B) Probable s-IBM

Specimen: Suggestive light microscopic s-IBM (vacuolated fibers without any inflammation or 1-2 vacuoles with necrosis)

Request form: Typical symptoms/signs of s-IBM,

Group C) Questionable s-IBM

Specimen: Not suggesting s-IBM

Request form: May not suggest s-IBM but has working diagnosis as s-IBM.

All included biopsy slides were re-evaluated by one of the authors (PS).

As Istanbul University Neuromuscular Pathology Laboratory is the only laboratory which gives service to all hospitals in Istanbul, our numbers were projected to calculate the ‘estimated prevalence’ of s-IBM in Istanbul. Population of Istanbul was obtained from the population projection data of the Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT) of the Government of Turkey.

General and age-adjusted frequencies of Group A, Groups A+B and Groups A+B+C were calculated (per million) for the total population and for the population adjusted for age over 50.

Results

The general population and the population over age 50 of Istanbul at 2010 census given by TURKSTAT were 13.255.685 and 2.347.300 respectively.

Based on our definition, 9 patients qualified for most suggestive s-IBM diagnosis (Group A). This gave a calculated general prevalence of 0.679 X 10-6 and age adjusted prevalence of 3.834 X 10-6 for the Istanbul area. In order to prevent under-diagnosis, patients with probable s-IBM (Group B), a total of 5 patients, were also considered. The sum of groups A and B gave a prevalence rate of 1.056 X 10-6 and age adjusted prevalence of 5.964 X 10-6. Eleven other patients had questionable s-IBM. Patient numbers in groups A, B and C, and prevalence rates in groups A, A+B and A+B+C are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

General and age adjusted prevalence rates of s-IBM in Istanbul/Turkey and their comparison with the rates in previous reports.

| Present sudy | Prevıous populatıon studıes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A* | Group A+B** | Group A+B+C*** | Netherlands(3) | Western Australıa(5,2) | USA(6) (Conncticut) (Age >45) | |

| Authors | This study | Badrising et al. (2000) |

Phillips et al. (2000) (Needham et al. (2008)) |

Felice (2001) |

||

|

Prevalence (X10-6) |

0.7 (0.679) |

1.0 (1.056) |

1.9 (1.886) |

4.9 |

4.3 (14.9) |

10.7 |

| Age Adjusted Prevalence (X10-6) |

3.8 (3.834) |

6 (5.964) |

10.7 (10.651) |

16.0 |

35.3 (51.2) |

28.9 |

Group A: Most suggestive s-IBM

Group B: Probable s-IBM

Group C: Suspicious s-IBM

When the most suggestive s-IBM group was divided into periods of 1993-1999, 2000-2005 and 2005-2010 the numbers of patients were 2, 3 and 4 respectively.

Since Istanbul receives heavy migration from all regions of Turkey and ours is the only muscle pathology laboratory in Istanbul, projection of these figures to the Turkish population was considered to be reasonable and an estimate of the prevalence of s-IBM in Turkey was obtained.

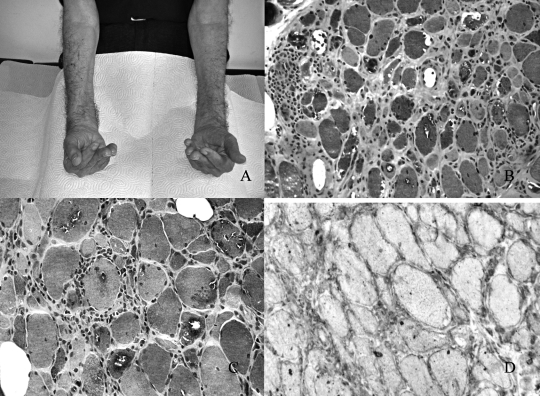

Figure 1.

A) Atrophy of the long finger flexors and inability to flex the fingers in one of our patients with typical clinical findings of s-IBM. B) Inflammation and rimmed vacuoles in one of our patients with most suggestive s-IBM histopathology (Engel's modified trichrome (E-MGT) stain, 250X) C) Inflammation and rimmed vacuoles in higher magnification in one of our patients with most suggestive s-IBM histopathology (E-MGT stain, 500X) D) Sarcolemmal MHC-1 staining in most fibers in the same patient (500X).

Discussion

Estimated prevalence and age adjusted prevalence rates of s-IBM in Istanbul/Turkey are found to be far lower than those in the previously reported population studies. This low prevalence rate could be explained by the unfamiliarity of the clinicians and the pathologist interpreting the biopsy data. Although this is a possibility, the pathologist had been trained to search for s-IBM and attempts of raising clinician awareness have been made at the national meetings since 1991. Another explanation could be the differing availability of medical investigations and differing tendencies to seek medical advice in case of muscle weakness among older people between countries. To overcome this obstacle, we divided the number of most suggestive group A patients into different periods. When the latest period of 2005-end-of-2010 was considered, the ‘estimated prevalence’ rates were still very low.

The low prevalence persisted even when groups A and B and further when all groups were merged (Group A+B+C) in order to prevent underestimation of s-IBM diagnosis. The comparison of our rates with the previously reported population studies on the ‘estimated prevalence’ of s-IBM is given in Table 1 (3-7).

This is the first attempt to study the estimated prevalence rate in a biopsy based manner in a Mediterranean country on the ‘estimated prevalence’ of s-IBM and it confirms unpublished observations from this region (2) and from a study in France in which, although not population based, the frequency of IBM was found to be 0.6 among 850 muscle biopsies (10).

Our findings show that prevalence of s-IBM varies greatly among countries and that this variation may be due to genetic, immunogenetic and/or environmental factors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our patients and the physicians who refereed their patient biopsiess to our laboratory. We also thank to Aygul Gündüz, Hatice Tasli and Sevil Kabadayi for their excellent technical and secretarial assistance.The first part of this study was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Council of Istanbul University (Project No: UDP-1385/27072007) and was presented at the 12th World Muscle Society Meeting, Giardini Naxos, Italy).

References

- 1.Askanas V, Engel WK. Molecular pathology and pathogenesis of inclusion-body myositis. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2005;67:114–120. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nedhams M, Mastaglia FL. Inclusion body myositis: current pathogenetic concepts and diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2007;7:620–621. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mastaglia FL. Sporadic inclusion body myositis: variability in prevalence and phenotype and influence of the MHC. Acta Myol. 2009;28:66–71. Review. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badrising UA, Maat-Schieman M, Duinen SG, et al. Epidemiology of inclusion body myositis in the Netherlands: a nationwide study. Neurology. 2000;55:1385–1387. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindberg C, Persson LI, Bjorkander J, et al. Inclusion body myositis: clinical, morphological, physiological and laboratory findings in 18 patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips BA, Zilko PJ, Mastaglia FL. Prevalence of sporadic inclusion body myositis in Western Australia. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:970–972. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(200006)23:6<970::aid-mus20>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felice KJ, North WA. Inclusion body myositis: Observation in 35 patients during an 8-year period. Medicine. 2001;80:320–327. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopkinson ND, Hunt J, Powell RJ, et al. Inclusion body myositis: an underdiagnosed condition? Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:147–151. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benveniste O, Hilton-Jones D. International Workshop on Inclusion Body Myositis held at the Institute of Myology, Paris, on 29 May 2009. Neuromusc Disord. 2010;20:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhiri C, Gherardi R. Inclusion body myositis in French patients: A clinicopathological evaluation. Neuropathol Appl Neuropathol. 1990;16:333–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1990.tb01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]