The mitotic exit network (MEN), a Ras-like GTPase signaling cascade, regulates exit from mitosis in budding yeast. The authors demonstrated that restricting MEN activity to anaphase can occur in a Tem1 GTPase-independent manner and identified the Polo kinase Cdc5 as the mediator of this control. In addition, both Tem1 and Cdc5 are required to recruit the MEN kinase Cdc15 to spindle pole bodies (SPBs), which is both necessary and sufficient to induce MEN signaling. Thus, Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector of two essential cell cycle oscillators.

Keywords: Cdc14, Cdc15, Cdc5, mitotic exit network, NDR kinase, Polo kinase, Tem1

Abstract

In budding yeast, a Ras-like GTPase signaling cascade known as the mitotic exit network (MEN) promotes exit from mitosis. To ensure the accurate execution of mitosis, MEN activity is coordinated with other cellular events and restricted to anaphase. The MEN GTPase Tem1 has been assumed to be the central switch in MEN regulation. We show here that during an unperturbed cell cycle, restricting MEN activity to anaphase can occur in a Tem1 GTPase-independent manner. We found that the anaphase-specific activation of the MEN in the absence of Tem1 is controlled by the Polo kinase Cdc5. We further show that both Tem1 and Cdc5 are required to recruit the MEN kinase Cdc15 to spindle pole bodies, which is both necessary and sufficient to induce MEN signaling. Thus, Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector of two essential cell cycle oscillators: the Polo kinase Cdc5 synthesis/degradation cycle and the Tem1 G-protein cycle. The Cdc15-dependent integration of these temporal (Cdc5 and Tem1 activity) and spatial (Tem1 activity) signals ensures that exit from mitosis occurs only after proper genome partitioning.

The creation of a daughter cell requires the faithful duplication and segregation of the genome. The success of this process necessitates the temporal and spatial coordination of genome segregation with the final cell cycle transition, exit from mitosis, when the mitotic spindle is disassembled, nuclei are reformed, and cytokinesis splits the cell into two. In the absence of such coordination, significant genetic and epigenetic changes occur. Thus, as might be expected, the inability to coordinate genome segregation with exit from mitosis is strongly associated with cancer (Kops et al. 2005; Gonzalez 2007).

In budding yeast, exit from mitosis is controlled by the essential protein phosphatase Cdc14. Cdc14 antagonizes mitotic cyclin-dependent kinases (Clb-CDKs), the inactivation of which is essential for exit from mitosis (Jaspersen et al. 1998; Visintin et al. 1998; Zachariae et al. 1998). Cdc14 activity is tightly regulated. In cell cycle stages prior to anaphase, Cdc14 is sequestered within the nucleolus as a result of its association with its nucleolar-localized inhibitor, Cfi1/Net1 (Shou et al. 1999; Visintin et al. 1999). Upon anaphase entry, Cdc14 is released from the nucleolus and spreads throughout the nucleus and, to a significantly lesser extent, the cytoplasm. This early anaphase release of Cdc14 is mediated by the FEAR network and results in a pulse of Cdc14 activity (Pereira et al. 2002; Stegmeier et al. 2002; Yoshida et al. 2002). While not essential, FEAR network-mediated release of Cdc14 from the nucleolus is crucial for the accurate execution of anaphase (Rock and Amon 2009). Cdc14 release from the nucleolus during late anaphase is promoted by the mitotic exit network (MEN), which drives the sustained release of Cdc14 in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm and results in exit from mitosis (Stegmeier and Amon 2004).

The MEN is a Ras-like GTPase signal transduction cascade (see Figure 7B, below, for a pathway diagram; for review, see Stegmeier and Amon 2004). As in other G-protein signaling pathways, the GTPase Tem1 is thought to be the central switch regulating MEN activity (Cooper and Nelson 2006; Wang and Ng 2006; Geymonat et al. 2009; Chan and Amon 2010). Tem1 is negatively regulated by its two-component GTPase-activating protein (GAP), Bub2–Bfa1. The Bub2–Bfa1 complex is regulated by two protein kinases. The Polo kinase Cdc5 phosphorylates Bfa1, which reduces Bub2–Bfa1 GAP activity. The protein kinase Kin4 functions in opposition to Cdc5, phosphorylating Bfa1 and thus rendering the GAP insensitive to Cdc5-dependent inhibitory phosphorylation (Maekawa et al. 2007). Tem1 is positively regulated by Lte1, which inhibits Kin4 in the bud (Bertazzi et al. 2011; Falk et al. 2011).

Figure 7.

A model for the coordination of exit from mitosis with spatial and temporal cues. (A) Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector of Tem1 and Cdc5 activity, both of which are required for the association of Cdc15 with SPBs. See the text for details. (B) Multiple signals control MEN activity. The core MEN components are shown in blue, activators of the MEN are shown in green, and inhibitors of the MEN are shown in red. Experimentally validated interactions are shown with solid lines, and more speculative interactions are shown with dashed lines. See the text for details.

During late anaphase, Tem1-GTP is thought to bind to and activate the protein kinase Cdc15, which then activates the downstream kinase Dbf2 associated with its activating subunit, Mob1. Based on binding data and homology with known scaffolds, Nud1 is thought to function as a scaffold for the core MEN components Tem1, Bub2–Bfa1, Cdc15, and Dbf2-Mob1 at spindle pole bodies (SPBs) (Gruneberg et al. 2000; Valerio-Santiago and Monje-Casas 2011). Tem1 SPB localization is essential for MEN activation, and it is thought that SPB localization of Cdc15, Dbf2, and Mob1 is also essential (Valerio-Santiago and Monje-Casas 2011). Activation of Dbf2-Mob1 results, at least in part, in the phosphorylation of Cdc14's nuclear localization sequence and causes the retention of Cdc14 in the cytoplasm, where it can act on its substrates (Mohl et al. 2009). Activation of the MEN in late anaphase is essential for the sustained release of Cdc14 from the nucleolus, which ultimately promotes exit from mitosis.

The mechanisms by which MEN activity and exit from mitosis are temporally and spatially coordinated with genome segregation are beginning to be understood. MEN activity is controlled by spindle position. When the anaphase spindle is not correctly aligned along the mother–daughter cell axis, MEN signaling is inhibited (Yeh et al. 1995). This spindle position control of MEN signaling is accomplished by a system composed of a MEN inhibitory and a MEN-activating zone and a sensor that moves between them. The MEN inhibitor Kin4 is located in the mother cell, the MEN activator Lte1 is located in the bud, and the MEN GTPase Tem1 is localized to the SPB (Bardin et al. 2000; Pereira et al. 2000; D'Aquino et al. 2005; Maekawa et al. 2007). Only when the MEN-bearing SPB escapes the MEN inhibitor Kin4 in the mother cell and moves into the bud where the MEN activator Lte1 resides can exit from mitosis occur. In this manner, spatial information is sensed and translated to regulate MEN activity.

Spindle position cannot be the only event controlling MEN activity, as exit from mitosis occurs at the appropriate time in lte1Δ or kin4Δ cells with correctly positioned spindles. Here, we describe the identification of a novel role for Cdc5 in regulating the timing of MEN activation. Interestingly, this essential Cdc5-dependent MEN-activating signal does not regulate the GTPase Tem1, but rather the Tem1 effector Cdc15. We found that Cdc5 is essential for the anaphase-specific recruitment of Cdc15 to SPBs. Furthermore, the artificial targeting of Cdc15 to the SPB bypasses the requirement for both Tem1 and Cdc5 in MEN activation. Our results indicate that multiple signals converge on the MEN effector kinase Cdc15 to integrate spatial (spindle position) and temporal (Cdc5 activation) cues with mitotic exit. Thus, Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector, integrating spatial and temporal signals to ensure that exit from mitosis only occurs after proper genome partitioning.

Results

LTE1 and KIN4-independent activation of the MEN in anaphase

LTE1 and KIN4 are the central mediators of MEN regulation by spindle position (Bardin et al. 2000; Pereira et al. 2000; Castillon et al. 2003; D'Aquino et al. 2005; Pereira and Schiebel 2005; Geymonat et al. 2009; Bertazzi et al. 2011; Falk et al. 2011). The subcellular partitioning of these two proteins ensures that cells that have a mispositioned anaphase spindle do not prematurely activate the MEN. It is unclear, however, whether LTE1 and KIN4 are also important for regulating the proper timing of MEN activation in cells where spindles are correctly aligned along the mother–bud axis. To address this question, we examined the consequences of deleting KIN4 and LTE1 on MEN activity. Cells were arrested in G1 using pheromone and then released to allow them to progress through the cell cycle in a synchronous manner. MEN activity was monitored by measuring the kinase activity of the most downstream MEN kinase, Dbf2-Mob1. Dbf2 kinase activity was restricted to anaphase in wild-type cells (Fig. 1A,B; Toyn and Johnston 1994). Similar results were obtained in lte1Δ kin4Δ cells (Fig. 1A,B). Thus, there must exist Kin4- and Lte1-independent mechanisms that restrict MEN activity to anaphase in cells with correctly positioned spindles.

Figure 1.

Anaphase-specific activation of the MEN in the absence of TEM1. (A,B) Wild-type (A2747) and lte1Δ kin4Δ (A26379) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEP medium containing glucose (YEPD). When the arrest was complete (after 150 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPD medium. After 80 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was re-added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; A), anaphase spindles (closed circles; A), and 3HA-Cdc14 released from the nucleolus (open circles; A), and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; B) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; B) were determined at the indicated times. (C) Wild-type (A2747) and tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were spotted on YEP plates containing raffinose and galactose (YEPRG) at 30°C. Approximately 3 × 104 cells were deposited in the first spot, and each subsequent spot is a 10-fold serial dilution. The picture shown depicts 3 d of growth. (D,E) Wild-type (A2747) and tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 50 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPRG medium. After 60 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; D), anaphase spindles (closed circles; D), and 3HA-Cdc14 released from the nucleolus (open circles; D), and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; E) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; E) were determined at the indicated times. (F) The amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 from E was determined by quantitative autoradiography and quantitative Western blot, respectively. Shown is the specific Dbf2-associated kinase activity.

Anaphase-specific activation of the MEN in the absence of TEM1

Our data indicate that regulatory mechanisms other than spindle position control MEN activity. To identify these signals, we first asked whether, as in other GTPase signaling cascades, all critical MEN regulation is mediated by the GTPase Tem1. To this end, we measured Dbf2 kinase activity in cells lacking the essential MEN GTPase Tem1 but kept alive by overexpression of CDC15 (henceforth tem1Δ CDC15-UP) (Pereira et al. 2000). Surprisingly, growth of tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells was indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells (Fig. 1C), and cell cycle progression occurred with near wild-type kinetics (Fig. 1D). Even more remarkable was the observation that Dbf2 kinase activity remained restricted to anaphase in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells, although activation was slightly delayed (Fig. 1E,F).

Control of MEN activity by spindle position was, however, lost in the tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain. Cells lacking cytoplasmic dynein (dyn1Δ cells) frequently misposition their spindles at low temperature and arrest in anaphase because the MEN GTPase Tem1 is inhibited by Bub2–Bfa1 (for review, see Fraschini et al. 2008). When the GAP is inactivated by deleting BUB2 or BFA1, cells with mispositioned spindles will not arrest in anaphase, but rather exit mitosis to produce anucleate and multinucleate cells (Supplemental Fig. 1; Bardin et al. 2000; Bloecher et al. 2000; Pereira et al. 2000). As in bub2Δ cells, tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells did not arrest in anaphase in response to spindle misposition (Supplemental Fig. 1). Our data confirm that spindle position control of the MEN is mediated by Tem1. Our data also indicate that the Tem1 GTPase is not the sole switch controlling MEN activity and that there must exist GTPase-independent mechanisms of MEN regulation that restrict Dbf2-Mob1 kinase activity to anaphase in an unperturbed cell cycle.

The FEAR network is not required for MEN activity in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells

The phosphatase Cdc14 is an activator of the MEN (Jaspersen and Morgan 2000; Stegmeier et al. 2002; Konig et al. 2010). Cdc14 activated by the FEAR network dephosphorylates Cdc15 and Mob1 and thereby promotes their activity (see Figure 7B, below). Although not essential for MEN activation, inactivation of the FEAR network leads to a delay in MEN activation, as judged by Dbf2 kinase activity (Stegmeier et al. 2002). To determine whether the FEAR network was also required for MEN activity in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells, we examined the consequences of deleting FEAR network components in this strain. SPO12; its close homolog, BNS1; and SLK19 are components of the FEAR network; loss-of-function mutations in these genes inactivate the FEAR network and greatly reduce the release of Cdc14 from the nucleolus in early anaphase (Stegmeier et al. 2002; Visintin et al. 2003). Deletion of these FEAR network components did not affect the growth of tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells (Fig. 2A). More importantly, inactivation of the essential FEAR network component Separase (Esp1) or the ultimate FEAR network effector Cdc14 had a similar effect on the kinetics of Dbf2 activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells as in wild-type cells. Dbf2 kinase activation was delayed by ∼10 min (Fig. 2B–D; Supplemental Fig. 2). Our results indicate that the FEAR network regulates MEN activity in tem1Δ CDC15-UP and wild-type cells in a similar manner. Thus, the FEAR network promotes but is not essential for the anaphase-specific activation of the MEN in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells.

Figure 2.

The FEAR network is not required for Dbf2 activity in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells. (A) Wild-type (A2747), tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670), tem1Δ spo12Δ bns1Δ CDC15-UP (A23392), and tem1Δ slk19Δ CDC15-UP (A23387) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were spotted on YEPRG plates, as in Figure 1C. (B,C) tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A23782) and tem1Δ cdc14-3 CDC15-UP (A23712) cells containing a 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium at room temperature. Thirty minutes prior to release, the cells were shifted to 35°C. When the arrest was complete (after 3 h 30 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPRG medium at 35°C. After 65 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was re-added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares, B) and anaphase spindles (closed circles, B) and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase, C) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP, C) were determined at the indicated times. (D) The amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 from C was determined as in Figure 1F. Shown is the specific Dbf2-associated kinase activity. Note that the specific Dbf2-associated kinase activity continues to rise in the tem1Δ cdc14-3 CDC15-UP strain as a result of a prolonged anaphase arrest.

Anaphase entry is not required for MEN activity in the absence of TEM1

We next sought to determine the mechanism underlying the GTPase-independent activation of the MEN in anaphase. We first asked whether entry into anaphase was a prerequisite for MEN activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells. The fact that MEN activation occurred with similar kinetics in tem1Δ CDC15-UP and tem1Δ CDC15-UP esp1-1 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2), which cannot undergo anaphase spindle elongation due to an inability to eliminate sister chromatid cohesion, already suggested that spindle elongation was not essential for MEN activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells.

To determine whether other aspects of anaphase entry were necessary for MEN activation, we arrested tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells in metaphase. Entry into anaphase is triggered by the activation of a ubiquitin ligase known as APC/CCdc20. Activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint by microtubule depolymerization results in the inhibition of APC/CCdc20 and arrests cells in metaphase (Musacchio and Salmon 2007). We found that entry into anaphase was not required for Dbf2-Mob1 activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells. tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells activated Dbf2-Mob1 with nearly identical kinetics in the presence or absence of the microtubule depolymerizing drug nocodazole (Supplemental Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained when anaphase entry was blocked by depletion of the APC/C coactivator CDC20 (JM Rock, unpubl.). Thus, although MEN activity is restricted to anaphase in an unperturbed cell cycle, anaphase entry is not a prerequisite for MEN activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells. In contrast, anaphase entry is required to activate the MEN in cells with a wild-type MEN. Dbf2 activation is greatly delayed in cdc23-1 mutants, which are defective in APC/C activity (Visintin and Amon 2001). We conclude that the dependence of MEN activation on anaphase entry is mediated by the MEN GTPase Tem1. However, the observation that MEN activation occurs 70 min after pheromone release irrespective of whether tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells enter anaphase (Supplemental Fig. 3) indicates that a Tem1 GTPase-independent MEN regulatory timing mechanism must exist. Furthermore, this timing mechanism must be independent of Separase and APC/CCdc20 activation.

Polo kinase Cdc5 controls MEN activity in the absence of TEM1

The Polo kinase Cdc5 is a key regulator of exit from mitosis (Lee et al. 2005). As a component of the FEAR network, Cdc5 promotes the release of Cdc14 from the nucleolus during early anaphase, which then promotes MEN activity (Stegmeier et al. 2002; Visintin et al. 2003). Cdc5 also regulates the MEN GAP Bub2–Bfa1. Cdc5 phosphorylates Bfa1, which reduces Bub2–Bfa1 GAP activity (Hu et al. 2001; Geymonat et al. 2003). Could Cdc5 have additional roles in regulating the MEN and confer MEN activation in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells? If Cdc5 was required for MEN activity in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells, then inactivating CDC5 should abrogate MEN activation. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that the tem1Δ CDC15-UP allele combination exhibits synthetic lethality with the temperature-sensitive cdc5-1 and cdc5-2 alleles at the permissive temperature (data not shown). However, we were able to construct a tem1Δ CDC15-UP cdc5-7 strain. We found that inactivation of CDC5 abolishes the ability of the tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain to activate Dbf2-Mob1 (Fig. 3A,B). We conclude that the Polo kinase Cdc5 is essential to activate the MEN in the absence of TEM1.

Figure 3.

Polo-like kinase Cdc5 controls MEN activity in the absence of TEM1. (A,B) tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670) and tem1Δ cdc5-7 CDC15-UP (A24305) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium at 30°C. Thirty minutes prior to release, the cells were shifted to 37°C. When the arrest was complete (after 3 h), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPRG medium at 37°C. After 65 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; A) and anaphase spindles (closed circles; B) and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; B) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; B) were determined at the indicated times. (C,D) tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670) and tem1Δ MET25-CDC5Δdb CDC15-UP (A25175) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. Ninety minutes prior to release, the cells were transferred to −Met medium containing raffinose and galactose (−MetRG; to induce the expression of Cdc5Δdb) supplemented with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL). When the arrest was complete (after 3 h), cells were released into pheromone-free −MetRG medium. After 70 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was re-added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; C) and anaphase spindles (closed circles; C) and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; D) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; D) were determined at the indicated times.

Is Cdc5 also sufficient for MEN activation in a tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain? Cdc5 protein levels are tightly regulated during the cell cycle. Cdc5 is absent during G1, begins to accumulate late in S phase, and peaks at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition. During exit from mitosis, Cdc5 is rapidly degraded by the APC/CCdh1 (Charles et al. 1998; Cheng et al. 1998; Shirayama et al. 1998). If Cdc5 was limiting for MEN activation in a tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain, then the premature expression of Cdc5 might result in the premature activation of the MEN. To test this hypothesis, we expressed a stable form of Cdc5 (Cdc5Δdb) from the conditional MET25 promoter in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells. We found that the premature accumulation of Cdc5 results in the premature activation of Dbf2-Mob1 in a tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain (Fig. 3C,D). It should be noted that the premature activation of Dbf2-Mob1 upon Cdc5Δdb expression is likely due to the premature activation of both the FEAR network and the MEN. Our results demonstrate that Cdc5 is essential for MEN activation in the absence of Tem1 GTPase function. Moreover, Cdc5 is sufficient to stimulate MEN signaling in other stages of the cell cycle.

Cdc5 promotes localization of Cdc15 to SPBs

To determine how Cdc5 controls MEN activity in the absence of Tem1, we examined the consequences of modulating Cdc5 activity on Cdc15 localization. Cdc15 localization in wild-type cells is dynamic. During G1, S, G2, and metaphase, Cdc15 is localized diffusely throughout the cytoplasm. Shortly after the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, Cdc15 localizes to the SPB that is pulled into the daughter and, in late anaphase, is found on both SPBs (Hu et al. 2001; Visintin and Amon 2001; Molk et al. 2004; Konig et al. 2010). Because Cdc15 recruitment to SPBs coincides with MEN activation and depends on TEM1, it is thought that localization of Cdc15 to SPB(s) is essential for MEN function (Visintin and Amon 2001).

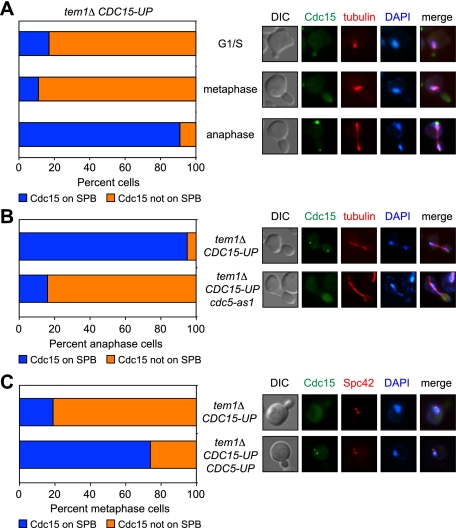

Although Cdc15 is highly overexpressed in the tem1Δ CDC15-UP strain (these cells harbor two overexpression constructs: GAL-CDC15 and GPD-CDC15), Cdc15 did not localize to SPBs prematurely, and association with this organelle remained largely restricted to anaphase (Fig. 4A). The anaphase-restricted Cdc15 SPB localization in tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells suggests a simple possible mechanism by which Cdc5 activates the MEN in parallel to Tem1: Cdc5 functions to promote Cdc15 SPB localization. To test this prediction, we followed Cdc15 localization in tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP cells containing an inhibitor-sensitive allele of CDC5 (cdc5-as1). In the presence of the inhibitor, Cdc15 is no longer able to localize to SPBs in the tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP cdc5-as1 cells (Fig. 4B). As CDC5 is sufficient to activate the MEN in the absence of Tem1 (Fig. 3D), it might be expected that the premature expression of Cdc5 results in the premature loading of Cdc15 onto SPBs. Indeed, we found that the premature activation of Cdc5 with the CDC5Δdb allele led to the premature recruitment of Cdc15 to SPBs in metaphase (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data indicate that CDC5 functions in parallel to TEM1 to promote the association of Cdc15 with SPBs.

Figure 4.

Cdc5 promotes localization of Cdc15 to SPBs. (A) tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP (A25630) cells containing a mCherry-Tub1 fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 50 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPRG medium and imaged after a brief paraformaldehyde fixation. Cell cycle stage was determined based on spindle morphology and correlated with Cdc15 localization at SPBs (n ≥ 100 cells for each cell cycle stage). Representative images of G1/S, metaphase, and anaphase cells are shown. Cdc15 is shown in green, microtubules are shown in red, and DNA is shown in blue. (B) tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP (A25630) and tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP cdc5-as1 (A25633) cells containing a mCherry-Tub1 fusion protein were arrested in G1 as in A. Cells were released into pheromone-free YEPRG medium supplemented with 5 μM CMK (cdc5-as1 inhibitor). Cells were scored as in A. Representative images of anaphase cells are shown. (C) tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP (A25744) and tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP MET25-CDC5ΔN70 (tem1Δ CDC15-eGFP-UP CDC5-UP; A25983) cells containing a Spc42-mCherry fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium supplemented with 8 mM methionine. Ninety minutes prior to release, the cells were transferred to −MetRG medium (to induce the expression of Cdc5ΔN70) supplemented with α-factor pheromone. When the arrest was complete (after 3 h), cells were released into pheromone-free −MetRG medium. Cells were imaged and scored as in A. Representative images of metaphase cells are shown. Cdc15 is shown in green, Spc42 is shown in red, and DNA is shown in blue.

Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector of Tem1 and Cdc5 activity

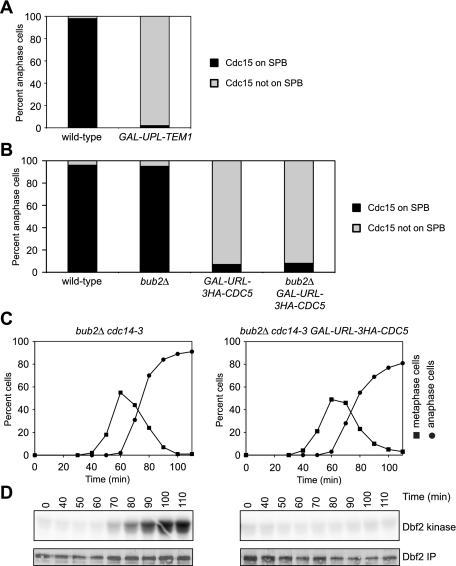

Our data suggest that both CDC5 and TEM1 function to promote Cdc15 SPB localization. If true, Cdc15 could function as a coincidence detector of Cdc5 and Tem1 activity. By this model, wild-type levels of Cdc15 might integrate essential inputs from Tem1 and Cdc5, both of which are required for MEN activation. A prediction of this hypothesis is that both Tem1 and Cdc5 should be essential for Cdc15 SPB localization and Dbf2-Mob1 activity in a wild-type cell. We first monitored Cdc15 localization in a strain depleted of Tem1 but wild-type for CDC5. Consistent with previously published data, depletion of Tem1 abolishes the localization of Cdc15 to SPBs (Fig. 5A; Johnson et al. 1992; Visintin and Amon 2001). CDC5 was also essential for Cdc15 association with SPBs. Cdc15 did not localize to SPBs in anaphase cells depleted of Cdc5 (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained in bub2Δ cells depleted of Cdc5 (Fig. 5B). Importantly, depletion of Cdc5 did not affect Tem1 localization to the SPB (Supplemental Fig. 4). These findings exclude the possibility that Cdc5 affects Cdc15 SPB localization indirectly by inactivating the Bub2–Bfa1 GAP complex or perturbing Tem1 SPB localization.

Figure 5.

Cdc15 functions as a coincidence detector of Tem1 and Cdc5 activity. (A) CDC15-eGFP (A26481) and CDC15-eGFP GAL-UPL-TEM1 (A27055) cells containing a mCherry-Tub1 fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. Ubiquitin-proline-LacZ (UPL) acts as a destabilizing module that permits rapid degradation of appended proteins. One hour prior to release, glucose was added to a final concentration of 2% (to repress expression of GAL-UPL-TEM1). When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 40 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPD medium. Cells were imaged and scored as in Figure 4A. (B) CDC15-eGFP (A26481), CDC15-eGFP bub2Δ (A26480), CDC15-eGFP GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 (A26556), and CDC15-eGFP bub2Δ GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 (A26558) cells containing a mCherry-Tub1 fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. Ubiquitin-arginine-LacZ (URL) acts as a destabilizing module that permits rapid degradation of appended proteins. Two hours prior to release, glucose was added to a final concentration of 2% (to repress expression of GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5). When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 45 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPD medium. Cells were imaged and scored as in Figure 4A. (C,D) bub2Δ cdc14-3 (A26844) and bub2Δ cdc14-3 GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 (A26842) cells containing a 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion protein were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium. Two hours prior to release, glucose was added to repress expression of GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5. When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 45 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPD medium. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; C) and anaphase spindles (closed circles; C) and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; D) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; D) were determined at the indicated times.

To further validate an essential role for Cdc5 in activating the MEN in wild-type cells, we monitored Dbf2 kinase activity in a synchronous cell cycle in a strain depleted for Cdc5. To control for Cdc5's role in activating the FEAR network and in inactivating Bub2–Bfa1, these experiments were performed in a cdc14-3 bub2Δ background. The BUB2 deletion eliminates the role of CDC5 in MEN GAP down-regulation, and the cdc14-3 mutation eliminates Cdc5-dependent FEAR network activation. As expected, Dbf2 kinase activity peaked in anaphase in the cdc14-3 bub2Δ strain (Fig. 5C,D). Consistent with the Cdc15 localization observations, Dbf2-Mob1 was not activated in the cdc14-3 bub2Δ strain depleted of Cdc5 (Fig. 5C,D). We conclude that Cdc5 is essential for MEN activation and regulates this pathway at multiple steps. Cdc5 stimulates MEN activity through its role in the FEAR network, partially inhibits the Tem1 GAP Bub2–Bfa1, and promotes the localization of Cdc15 to SPBs. Our data further indicate that Cdc15 behaves like a coincidence detector, requiring inputs from both Tem1 and Cdc5 to localize to the SPB and thus activate the MEN.

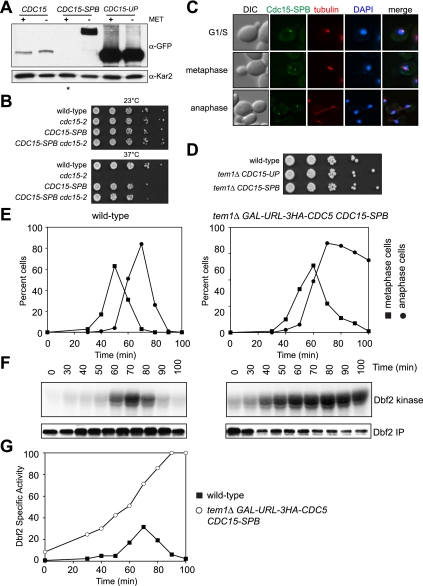

Targeting Cdc15 to the SPB bypasses the need for both Tem1 and Cdc5 in MEN activation

Localization of Cdc15 to the SPB is thought to be essential for MEN activation (Stegmeier and Amon 2004). Our observations suggest that the essential MEN-activating function of both Tem1 and Cdc5 is to promote Cdc15 SPB localization. To test this possibility, we asked whether artificially targeting Cdc15 to SPBs bypasses the need for Tem1 and Cdc5 in MEN activation. We fused the CDC15-eGFP ORF to the ORF of the SPB outer plaque component CNM67 to generate a Cdc15-eGFP-Cnm67 fusion protein (hereafter referred to as Cdc15-SPB). Expression of the fusion protein from the CDC15 promoter is lethal (data not shown). We therefore placed Cdc15-SPB under the transcriptional control of the low-strength conditional MET3 promoter. Induction of the Cdc15-SPB fusion was toxic (data not shown), but the fusion protein was well tolerated when the MET3 promoter was repressed. Under these conditions, the Cdc15-SPB fusion protein was detectable by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6C) but was not detectable by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6A, lane marked with asterisk). The fusion protein was nevertheless present at high enough levels under MET3-repressive conditions to allow the necessary experimental manipulations to follow. We therefore performed all experiments involving this fusion protein under conditions where the MET3 promoter was repressed.

Figure 6.

Targeting Cdc15 to SPBs bypasses the need for TEM1 and CDC5 in MEN activation. (A) CDC15-eGFP (CDC15; A20935), pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 (CDC15-SPB; A26417), and CDC15-eGFP-UP (CDC15-UP; A25515) cells were grown to log phase in either YEPRG + methionine (+MET) or −Met medium to determine the amount of Cdc15-eGFP (α-GFP) in cells. Kar2 was used as a loading control in Western blots. (B) Wild-type (A2587), cdc15-2 (A2597), pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 (CDC15-SPB; A26419), and pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 cdc15-2 (CDC15-SPB cdc15-2; A26413) cells were spotted on YEPRG plates supplemented with 8 mM methionine as in Figure 1C. The picture shown depicts 2 d of growth at 37°C and 3 d of growth at 23°C. (C) pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 (CDC15-SPB; A26486) cells containing a mCherry-Tub1 fusion protein were grown to log phase in YEPRG medium supplemented with 8 mM methionine and imaged after a brief paraformaldehyde fixation. Representative images of G1/S, metaphase, and anaphase cells are shown. (D) Wild-type (A2747), tem1Δ CDC15-UP (A22670), and tem1Δ pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 (tem1Δ CDC15-SPB; A26396) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were spotted on YEPRG plates supplemented with 8 mM methionine as in Figure 1C. The picture shown depicts 3 d of growth. (E,F) Wild-type (A2747) and tem1Δ GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 pMET3-CDC15-eGFP-CNM67 (tem1Δ GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 CDC15-SPB; A27051) cells containing 3HA-Cdc14 and 3MYC-Dbf2 fusion proteins were arrested in G1 with α-factor pheromone (5 μg/mL) in YEPRG medium supplemented with 8 mM methionine. Two hours prior to release, glucose was added (to repress expression of GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5). When the arrest was complete (after 2 h 50 min), cells were released into pheromone-free YEPD medium supplemented with 8 mM methionine. After 65 min, α-factor pheromone (10 μg/mL) was added to prevent entry into the subsequent cell cycle. The percentage of cells with metaphase spindles (closed squares; E) and anaphase spindles (closed circles; E) and the amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity (Dbf2 kinase; F) and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 (Dbf2 IP; F) were determined at the indicated times. (G) The amount of Dbf2-associated kinase activity and immunoprecipitated 3MYC-Dbf2 from F was determined as in Figure 1F. Shown is the specific Dbf2-associated kinase activity.

First, we confirmed the functionality of the fusion. While we were not able to measure kinase activity associated with the Cdc15-SPB fusion protein (presumably because the Cdc15-SPB protein is tightly bound to the SPB and thus is not amenable to standard immunoprecipitation kinase techniques), the CDC15-SPB fusion suppressed the temperature-sensitive lethality of cells harboring the cdc15-2 allele as the sole source of CDC15 (Fig. 6B). Thus, the Cdc15-SPB protein is active as a kinase and is capable of performing the essential function of Cdc15. The fusion protein also exhibited the expected localization pattern. Cdc15-SPB localizes to the SPB constitutively throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 6C; Supplemental Fig. 5). To determine whether the Cdc15-SPB fusion can support the essential functions of TEM1 and CDC5 in MEN activation, we constructed a tem1Δ GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 CDC15-SPB strain in which TEM1 was deleted and Cdc5 could be efficiently depleted (Bachmair et al. 1986). We found that tem1Δ cells are viable when they harbor the CDC15-SPB fusion (Fig. 6D); thus, the essential function of TEM1 can be bypassed by the CDC15-SPB allele. To determine whether CDC5 function in MEN activation was also bypassed by the Cdc15-SPB fusion protein, we examined Dbf2 kinase activity in tem1Δ cells that were also depleted for Cdc5. Strikingly, provision of the CDC15-SPB allele in the tem1Δ GAL-URL-3HA-CDC5 strain suppressed the defect in Dbf2-Mob1 activation observed in cells that lack TEM1 or CDC5 (cf. Figs. 5D and 6E–G; Visintin and Amon 2001). Moreover, Dbf2 kinase activity was both premature and hyperactive in this strain (Fig. 6F,G). Similar results were obtained in wild-type cells expressing the Cdc15-SPB fusion (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Our analysis of a C-terminally truncated CDC15 allele [GAL-GFP-CDC15(1–750)] is consistent with the idea that targeting Cdc15 to SPBs bypasses the requirement for both Tem1 and Cdc5 in MEN activation (Bardin et al. 2003). Like the Cdc15-SPB fusion, Cdc15(1–750) localized to the SPB throughout the cell cycle in a manner independent of Tem1 and Cdc5 (Supplemental Fig. 7A). Consistent with these observations, we found that Dbf2 kinase was both premature and hyperactive upon overexpression of Cdc15(1–750). Moreover, the overexpression of Cdc15(1–750) was sufficient to activate Dbf2-Mob1 in the absence of Cdc5 kinase activity (Supplemental Fig. 7B–G).

Interestingly, Dbf2 kinase activity still fluctuates during the cell cycle in cells in which Cdc15 localizes to SPBs constitutively (Supplemental Figs. 6–8). Thus, Dbf2-Mob1 kinase activity must be regulated by mechanisms in addition to Cdc15 SPB recruitment (see the Discussion). It should also be noted that, despite premature and hyperactive Dbf2 kinase activity in Cdc15-SPB-expressing cells, Cdc14 release from the nucleolus remained restricted to anaphase (Supplemental Figs. 6A, 8). This indicates that yet additional mechanisms control Cdc14 localization downstream from and/or in parallel to Dbf2-Mob1 (see the Discussion). We conclude that the sole essential MEN-activating function of both TEM1 and CDC5 is to target Cdc15 to SPBs.

Discussion

Multiple signals converge on Cdc15 to integrate MEN activity with other cellular events

The MEN is essential for exit from mitosis. The MEN GTPase Tem1 has been assumed to be the central switch in MEN regulation. We show here that robust MEN regulation occurs in a GTPase-independent manner and identify the Tem1 effector Cdc15 as an integrator of cell cycle signals. Cdc15 behaves like a coincidence detector (Fig. 7A), integrating inputs from two essential cell cycle oscillators: the Tem1 GTPase cycle and the Polo kinase Cdc5 synthesis/degradation cycle. The Cdc15-dependent integration of these temporal (Cdc5 and Tem1 activity) and spatial (Tem1 activity) signals ensures that exit from mitosis occurs only after proper genome partitioning. Indeed, reliance on the timing signal alone (tem1Δ CDC15-UP) results in the inability to coordinate MEN activity with spindle position and the inappropriate exit from mitosis in the presence of a mispositioned anaphase spindle (Supplemental Fig. 1). Tem1 and Cdc5 activity are read by the ability of Cdc15 to associate with the SPB. Artificially targeting Cdc15 to SPBs by fusing Cdc15 to an integral SPB component (Cdc15-SPB) bypasses the requirement for both proteins in MEN activation. Thus, it appears that recruitment of Cdc15 to SPBs is the essential function of Cdc5 and Tem1 in MEN activation.

It is unclear why Cdc15 recruitment to SPBs is essential for MEN activity. Cdc15 kinase activity, at least as measured by in vitro immunoprecipitation kinase assays, does not change during the cell cycle (Jaspersen et al. 1998). It is possible that Cdc15 could be activated by a SPB-associated protein, but such activation may not be detectable using standard immunoprecipitation kinase assay conditions. An alternative but not mutually exclusive possibility is that a SPB scaffold, such as Nud1, may be required to increase the efficiency of interaction between MEN components to promote Cdc15-dependent Dbf2-Mob1 activation. Although we do not yet know why Cdc15 must associate with SPBs, we have some understanding of how this association occurs. Tem1 recruits Cdc15 to SPBs via a region in Cdc15 immediately adjacent to its kinase domain (Asakawa et al. 2001). How Cdc5 promotes Cdc15 SPB localization is unknown. Preliminary data suggest that Cdc15 is not a Cdc5 substrate. 32P incorporation into Cdc15 in vivo was not affected by modulating CDC5 activity (JM Rock, unpubl.). In addition, mutation of Cdc5 consensus binding sites (SSP to AAP) in Cdc15 did not abrogate Cdc15-dependent MEN activation (JM Rock, unpubl.). These results and several other observations raise the possibility that the putative SPB anchor for Cdc15, Nud1, might be Cdc5's essential MEN-activating target: (1) Nud1 is thought to bind to and recruit Cdc15 to the SPB (Stegmeier and Amon 2004), (2) nud1 temperature-sensitive mutants arrest in late anaphase with an inactive MEN (Gruneberg et al. 2000; Visintin and Amon 2001), (3) Nud1 is a substrate of Cdc5 in vivo and in vitro (Maekawa et al. 2007; Park et al. 2008), and (4) Nud1 hyperphosphorylation coincides with Cdc15 recruitment to SPBs (Visintin et al. 2003; Maekawa et al. 2007; Park et al. 2008). Cdc5 could phosphorylate Nud1 in mitosis, thereby creating a phospho-dependent SPB-binding site for Cdc15. As Nud1 is the most extensively phosphorylated SPB component (>50 phosphosites) (Keck et al. 2011), testing this hypothesis will be extremely challenging. It is important to note, however, that the CDC15-SPB fusion does not suppress the temperature-sensitive lethality of cells harboring the nud1-44 allele as the sole source of NUD1 (JM Rock, unpubl.). Thus, unlike TEM1 and CDC5, NUD1 has essential roles in MEN signaling in addition to recruiting Cdc15 to SPBs.

Novel temporal regulators of the MEN

Our data indicate that MEN activity is regulated by multiple inputs (Fig. 7B). The dependence of MEN activity on CDC5 ensures that the MEN can only be activated during G2 and mitosis, when Cdc5 is active. Our data also indicate that restricting MEN activity to anaphase is mediated by the GTPase Tem1. In wild-type cells arrested in metaphase, Dbf2-Mob1 activity remains low. In tem1Δ CDC15-UP cells arrested in metaphase, however, Dbf2-Mob1 is activated. Thus, an unknown anaphase event, likely under the control of the APC/CCdc20, must be responsible for activating Tem1 at anaphase onset or keeping Tem1 inactive in earlier cell cycle stages. While the FEAR network contributes to activating the MEN in anaphase, the subtle effects of inactivating the FEAR network on mitotic exit kinetics argues that alternative pathways must regulate Tem1 activity.

As elaborated in this study, Cdc5 regulates the cell cycle-dependent localization of Cdc15 to SPBs. Despite the importance of regulating Cdc15 recruitment to SPBs, it is clear that additional mechanisms function downstream from and/or in parallel to Cdc15 to regulate exit from mitosis. Our data suggest that Dbf2 kinase activity is controlled by mechanisms in addition to Cdc15 recruitment to SPBs. Even though Dbf2 is hyperactive and active well before metaphase in CDC15-SPB cells, Dbf2 kinase activity nevertheless fluctuates during the cell cycle, being low in G1 and peaking in early anaphase (Supplemental Figs. 6–8). Thus, there must exist a signal that promotes Dbf2 kinase activity as cells progress through S phase and mitosis or inhibits Dbf2 kinase activity in G1. Given that Dbf2-Mob1 kinase activity mirrors Clb-CDK activity in CDC15-SPB and GAL-GFP-CDC15(1–750) cells, it is tempting to speculate that Clb-CDKs directly or indirectly control Dbf2 kinase activity in these cells.

Our data also indicate that Dbf2 kinase activation is necessary but not sufficient to promote Cdc14 release from the nucleolus. In CDC15-SPB cells, Dbf2-specific activity is more than five times that seen in wild-type cells, and substantial Dbf2-Mob1 kinase activity (equal to the peak seen in a wild-type cell cycle) is achieved well before metaphase in the CDC15-SPB strain. In GAL-GFP-CDC15(1–750) cells, the difference is even more striking, with Dbf2-specific activity levels >43 times that seen in wild-type cells. The difference in Dbf2-specific activity in these strains is likely due, at least in part, to the much higher expression levels of the GAL-GFP-CDC15(1–750) construct as compared with the MET3-CDC15-SPB construct. Despite premature and hyperactive Dbf2 kinase activity, Cdc14 is not released prematurely in these strains (Supplemental Figs. 6–8). The mechanisms that restrict Dbf2-Mob1-dependent Cdc14 release to anaphase are unknown. Given that the overexpression of Cdc5 in combination with the premature activation of the MEN is sufficient to drive Cdc14 out of the nucleolus in any cell cycle stage (Manzoni et al. 2010), we propose that Cdc5 plays yet an additional key role in regulating Cdc14 release downstream from and/or in parallel to Dbf2-Mob1.

Logic of MEN activation

Our results and those of previous studies suggest the following model for how MEN activity is restricted to anaphase and coupled to accurate spindle position by the integration of multiple spatial and temporal cues (Fig. 7B). As cells approach the metaphase-to-anaphase transition and Cdc5 kinase reaches high levels of activity, Cdc5 phosphorylates an as-yet-unidentified target, which primes the MEN for activation by creating conditions that promote the association of Cdc15 with the SPB. Cdc5 also phosphorylates Bub2–Bfa1, thereby lowering its GAP activity. At the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, Cdc14 activated by the FEAR network dephosphorylates Cdc15 and Mob1, thereby stimulating MEN activity. This couples full MEN activation with the onset of chromosome segregation, as components of the FEAR network are not only MEN activators but are also essential for inducing chromosome segregation. Additional unknown signals regulate Tem1 and Dbf2-Mob1 to restrict their activity to anaphase. Finally, spindle position is integrated with MEN regulation via Tem1. As the spindle elongates along the mother–daughter axis, the Tem1-bearing SPB leaves the MEN inhibitory zone in the mother cell (defined by Kin4) and enters the MEN-activating zone in the bud (defined by Lte1). This allows for the activation of Tem1 and recruitment of Cdc15 to SPBs. Additional signals functioning downstream from and/or in parallel to Dbf2-Mob1, and perhaps regulated by Cdc5, are needed to release Cdc14 from the nucleolus in anaphase in a sustained manner. While much remains to be learned about MEN regulation, it is clear that Cdc15 integrates both temporal (Cdc5 and Tem1) and spatial (Tem1) signals to mediate the robust and timely activation of the MEN in late anaphase.

MEN-like signaling pathways in other eukaryotes

The MEN is conserved in fission yeast, where it is called the septation initiation network (SIN) and regulates cytokinesis. Does Plo1 (Cdc5 homolog) regulate the SIN in a manner similar to the way Cdc5 regulates the MEN? plo1+ has been shown genetically to act as an activator of the SIN and placed to function upstream of spg1+ (Tem1 homolog) (Tanaka et al. 2001). That said, the strong similarities between the MEN and SIN, and particularly between Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cdc15 and its homolog in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Cdc7, suggest that Plo1 may also regulate the association of Cdc7 with SPBs. Cdc7 localizes to SPBs in mitosis, and this localization is regulated by both Spg1 and Plo1 (Sohrmann et al. 1998; Mulvihill et al. 1999). Both Cdc15 and Cdc7 can associate with SPBs in at least two ways: One is mediated by a GTPase interaction domain, and the other is mediated by an independent SPB localization domain (Asakawa et al. 2001; Bardin et al. 2003; Mehta and Gould 2006). Consistent with both modes of SPB localization being cell cycle-regulated, localization of Cdc7 to SPBs is restricted to mitosis even when Cdc7 is overexpressed. Finally, while the Cdc7–Spg1 interaction is essential for SIN activation in wild-type cells, overexpression of cdc7+ can suppress the lethality of a strain deleted for spg1+ (Schmidt et al. 1997). Thus, just as is the case for the MEN, there must exist GTPase-independent mechanisms of SIN activation, and these mechanisms might be mediated by Polo kinase.

The core MEN signaling module—consisting of Cdc15, Dbf2, Mob1, and Nud1—also exists in higher eukaryotes. In higher eukaryotes, these proteins are known as mammalian sterile-20-related kinases (MSTs; Cdc15 homolog), nuclear Dbf2-related kinases (NDRs; Dbf2 homolog), Mob1 coactivators, and scaffolding (Nud1 homolog) families. While there are few known roles for these proteins in regulating mitotic exit (Bothos et al. 2005), they are essential components of signaling pathways that regulate a multitude of other cellular processes. As part of the Hippo pathway, this signaling module is essential for the proper regulation of organ growth in Drosophila and vertebrates (Halder and Johnson 2011). Like their fungal counterparts, human NDR kinases and their Mob1 coactivators localize to centrosomes, the mammalian equivalent of SPBs (Hergovich et al. 2007; Wilmeth et al. 2010). Intriguingly, as is the case in S. cerevisiae (Luca et al. 2001; JM Rock, unpubl.), the localization of Mob1 isoforms to the centrosome is dependent on Polo-like kinase 1 activity (Wilmeth et al. 2010). Finally, we note that overexpression of human NDR1 results in centrosome overduplication as does overexpression of Polo-like kinase 4 (Plk4) (Habedanck et al. 2005; Hergovich et al. 2007). This raises the possibility that Plk4 plays a role in activating the MST/NDR1 signaling cascade. It will be interesting to explore whether or not Polo kinase activates NDR kinase signaling in higher eukaryotes.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and growth conditions

All strains are derivatives of W303 (A2587) and are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Growth conditions are described in the figure legends.

Plasmid construction

All plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Specifics of plasmid construction are detailed in the Supplemental Material.

Immunoblot analysis

For immunoblot analysis of Cdc15-eGFP, Cdc15-eGFP-Cnm67, GFP-Cdc15, GFP-Cdc15(1-750), Pgk1, and Kar2, cells were incubated for a minimum of 10 min in 5% trichloroacetic acid. The acid was washed away with acetone, and cells were pulverized with glass beads in 166 μL of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 2.75 mM DTT, complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) using a bead mill. Sample buffer was added, and the cell homogenates were boiled. Cdc15-eGFP, Cdc15-eGFP-Cnm67, GFP-Cdc15, and GFP-Cdc15(1–750) were detected using an anti-GFP antibody (Clontech, JL-8) at a 1:1000 dilution. Pgk1 was detected using an anti-Pgk1 antibody (Invitrogen) at a 1:5000 dilution. Kar2 was detected using a rabbit anti-Kar2 antiserum (Rose et al. 1989) at a 1:200,000 dilution.

Dbf2 kinase assays

Dbf2 kinase assays were performed as described previously (Visintin and Amon 2001) with the following modifications: Approximately 1.5 mg of total protein was used per immunoprecipitation, and kinase reactions were incubated for 45 min with gentle mixing. Histone H1 phosphorylation was quantified using the PhosphorImaging system. Western blots were quantified using ECL Plus (GE Healthcare) and fluorescence imaging. Quantifications were performed using NIH ImageQuant software.

Fluorescence microscopy

Indirect in situ immunofluorescence methods to detect Tub1 were performed as previously described (Kilmartin and Adams 1984). For imaging of Cdc15-eGFP and Cdc15-eGFP-Cnm67, cells were fixed for 2 min in 4% paraformaldehyde (in 3.4% sucrose solution). Cells were washed once in KPO4/sorbitol (1.2 M sorbitol, 0.1 M KPO4 at pH 7.5) and resuspended in KPO4/sorbitol supplemented with 1% Triton. Prior to imaging, cells were stained with Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, P36935). Cells were imaged within 24 h on a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope and a Hamamatsu OCRA-ER digital camera.

FACs

Flow cytometric DNA quantitation was performed as described by Haase and Reed (2002).

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Solomon, Iain Cheeseman, Rosella Visintin, Fernando Monje-Casas, Leigh Baxt, Leon Chan, Anupama Seshan, and members of the Amon laboratory for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM056800 to A.A.) and an NSF Predoctoral Fellowship (to J.M.R.). A.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.17257711.

References

- Asakawa K, Yoshida S, Otake F, Toh-e A 2001. A novel functional domain of Cdc15 kinase is required for its interaction with Tem1 GTPase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 157: 1437–1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A 1986. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science 234: 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin AJ, Visintin R, Amon A 2000. A mechanism for coupling exit from mitosis to partitioning of the nucleus. Cell 102: 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin AJ, Boselli MG, Amon A 2003. Mitotic exit regulation through distinct domains within the protein kinase Cdc15. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5018–5030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertazzi DT, Kurtulmus B, Pereira G 2011. The cortical protein Lte1 promotes mitotic exit by inhibiting the spindle position checkpoint kinase Kin4. J Cell Biol 193: 1033–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloecher A, Venturi GM, Tatchell K 2000. Anaphase spindle position is monitored by the BUB2 checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol 2: 556–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothos J, Tuttle RL, Ottey M, Luca FC, Halazonetis TD 2005. Human LATS1 is a mitotic exit network kinase. Cancer Res 65: 6568–6575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillon GA, Adames NR, Rosello CH, Seidel HS, Longtine MS, Cooper JA, Heil-Chapdelaine RA 2003. Septins have a dual role in controlling mitotic exit in budding yeast. Curr Biol 13: 654–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LY, Amon A 2010. Spindle position is coordinated with cell-cycle progression through establishment of mitotic exit-activating and -inhibitory zones. Mol Cell 39: 444–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles JF, Jaspersen SL, Tinker-Kulberg RL, Hwang L, Szidon A, Morgan DO 1998. The Polo-related kinase Cdc5 activates and is destroyed by the mitotic cyclin destruction machinery in S. cerevisiae. Curr Biol 8: 497–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Hunke L, Hardy CF 1998. Cell cycle regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae polo-like kinase cdc5p. Mol Cell Biol 18: 7360–7370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Nelson SA 2006. Checkpoint control of mitotic exit—do budding yeast mind the GAP? J Cell Biol 172: 331–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aquino KE, Monje-Casas F, Paulson J, Reiser V, Charles GM, Lai L, Shokat KM, Amon A 2005. The protein kinase Kin4 inhibits exit from mitosis in response to spindle position defects. Mol Cell 19: 223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk JE, Chan LY, Amon A 2011. Lte1 promotes mitotic exit by controlling the localization of the spindle position checkpoint kinase Kin4. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 12584–12590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraschini R, Venturetti M, Chiroli E, Piatti S 2008. The spindle position checkpoint: how to deal with spindle misalignment during asymmetric cell division in budding yeast. Biochem Soc Trans 36: 416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geymonat M, Spanos A, Walker PA, Johnston LH, Sedgwick SG 2003. In vitro regulation of budding yeast Bfa1/Bub2 GAP activity by Cdc5. J Biol Chem 278: 14591–14594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geymonat M, Spanos A, de Bettignies G, Sedgwick SG 2009. Lte1 contributes to Bfa1 localization rather than stimulating nucleotide exchange by Tem1. J Cell Biol 187: 497–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez C 2007. Spindle orientation, asymmetric division and tumour suppression in Drosophila stem cells. Nat Rev Genet 8: 462–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneberg U, Campbell K, Simpson C, Grindlay J, Schiebel E 2000. Nud1p links astral microtubule organization and the control of exit from mitosis. EMBO J 19: 6475–6488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase SB, Reed SI 2002. Improved flow cytometric analysis of the budding yeast cell cycle. Cell Cycle 1: 132–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Wilkinson CJ, Nigg EA 2005. The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat Cell Biol 7: 1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Johnson RL 2011. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development 138: 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergovich A, Lamla S, Nigg EA, Hemmings BA 2007. Centrosome-associated NDR kinase regulates centrosome duplication. Mol Cell 25: 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Wang Y, Liu D, Li Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ 2001. Regulation of the Bub2/Bfa1 GAP complex by Cdc5 and cell cycle checkpoints. Cell 107: 655–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen SL, Morgan DO 2000. Cdc14 activates cdc15 to promote mitotic exit in budding yeast. Curr Biol 10: 615–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen SL, Charles JF, Tinker-Kulberg RL, Morgan DO 1998. A late mitotic regulatory network controlling cyclin destruction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 9: 2803–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES, Bartel B, Seufert W, Varshavsky A 1992. Ubiquitin as a degradation signal. EMBO J 11: 497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck JM, Jones MH, Wong CC, Binkley J, Chen D, Jaspersen SL, Holinger EP, Xu T, Niepel M, Rout MP, et al. 2011. A cell cycle phosphoproteome of the yeast centrosome. Science 332: 1557–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmartin JV, Adams AE 1984. Structural rearrangements of tubulin and actin during the cell cycle of the yeast Saccharomyces. J Cell Biol 98: 922–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig C, Maekawa H, Schiebel E 2010. Mutual regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase and the mitotic exit network. J Cell Biol 188: 351–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kops GJ, Weaver BA, Cleveland DW 2005. On the road to cancer: aneuploidy and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Park JE, Asano S, Park CJ 2005. Yeast polo-like kinases: functionally conserved multitask mitotic regulators. Oncogene 24: 217–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca FC, Mody M, Kurischko C, Roof DM, Giddings TH, Winey M 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mob1p is required for cytokinesis and mitotic exit. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6972–6983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa H, Priest C, Lechner J, Pereira G, Schiebel E 2007. The yeast centrosome translates the positional information of the anaphase spindle into a cell cycle signal. J Cell Biol 179: 423–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni R, Montani F, Visintin C, Caudron F, Ciliberto A, Visintin R 2010. Oscillations in Cdc14 release and sequestration reveal a circuit underlying mitotic exit. J Cell Biol 190: 209–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta S, Gould KL 2006. Identification of functional domains within the septation initiation network kinase, Cdc7. J Biol Chem 281: 9935–9941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohl DA, Huddleston MJ, Collingwood TS, Annan RS, Deshaies RJ 2009. Dbf2-Mob1 drives relocalization of protein phosphatase Cdc14 to the cytoplasm during exit from mitosis. J Cell Biol 184: 527–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molk JN, Schuyler SC, Liu JY, Evans JG, Salmon ED, Pellman D, Bloom K 2004. The differential roles of budding yeast Tem1p, Cdc15p, and Bub2p protein dynamics in mitotic exit. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1519–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill DP, Petersen J, Ohkura H, Glover DM, Hagan IM 1999. Plo1 kinase recruitment to the spindle pole body and its role in cell division in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell 10: 2771–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A, Salmon ED 2007. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 379–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CJ, Park JE, Karpova TS, Soung NK, Yu LR, Song S, Lee KH, Xia X, Kang E, Dabanoglu I, et al. 2008. Requirement for the budding yeast polo kinase Cdc5 in proper microtubule growth and dynamics. Eukaryot Cell 7: 444–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G, Schiebel E 2005. Kin4 kinase delays mitotic exit in response to spindle alignment defects. Mol Cell 19: 209–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G, Hofken T, Grindlay J, Manson C, Schiebel E 2000. The Bub2p spindle checkpoint links nuclear migration with mitotic exit. Mol Cell 6: 1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G, Manson C, Grindlay J, Schiebel E 2002. Regulation of the Bfa1p–Bub2p complex at spindle pole bodies by the cell cycle phosphatase Cdc14p. J Cell Biol 157: 367–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock JM, Amon A 2009. The FEAR network. Curr Biol 19: R1063–R1068 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MD, Misra LM, Vogel JP 1989. KAR2, a karyogamy gene, is the yeast homolog of the mammalian BiP/GRP78 gene. Cell 57: 1211–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Sohrmann M, Hofmann K, Woollard A, Simanis V 1997. The Spg1p GTPase is an essential, dosage-dependent inducer of septum formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev 11: 1519–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K 1998. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 17: 1336–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou W, Seol JH, Shevchenko A, Baskerville C, Moazed D, Chen ZW, Jang J, Charbonneau H, Deshaies RJ 1999. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97: 233–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrmann M, Schmidt S, Hagan I, Simanis V 1998. Asymmetric segregation on spindle poles of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe septum-inducing protein kinase Cdc7p. Genes Dev 12: 84–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Amon A 2004. Closing mitosis: the functions of the Cdc14 phosphatase and its regulation. Annu Rev Genet 38: 203–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Visintin R, Amon A 2002. Separase, polo kinase, the kinetochore protein Slk19, and Spo12 function in a network that controls Cdc14 localization during early anaphase. Cell 108: 207–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Petersen J, MacIver F, Mulvihill DP, Glover DM, Hagan IM 2001. The role of Plo1 kinase in mitotic commitment and septation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J 20: 1259–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyn JH, Johnston LH 1994. The Dbf2 and Dbf20 protein kinases of budding yeast are activated after the metaphase to anaphase cell cycle transition. EMBO J 13: 1103–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio-Santiago M, Monje-Casas F 2011. Tem1 localization to the spindle pole bodies is essential for mitotic exit and impairs spindle checkpoint function. J Cell Biol 192: 599–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Amon A 2001. Regulation of the mitotic exit protein kinases Cdc15 and Dbf2. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2961–2974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Craig K, Hwang ES, Prinz S, Tyers M, Amon A 1998. The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2: 709–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Hwang ES, Amon A 1999. Cfi1 prevents premature exit from mitosis by anchoring Cdc14 phosphatase in the nucleolus. Nature 398: 818–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Stegmeier F, Amon A 2003. The role of the polo kinase Cdc5 in controlling Cdc14 localization. Mol Biol Cell 14: 4486–4498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ng TY 2006. Phosphatase 2A negatively regulates mitotic exit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 17: 80–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmeth LJ, Shrestha S, Montano G, Rashe J, Shuster CB 2010. Mutual dependence of Mob1 and the chromosomal passenger complex for localization during mitosis. Mol Biol Cell 21: 380–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh E, Skibbens RV, Cheng JW, Salmon ED, Bloom K 1995. Spindle dynamics and cell cycle regulation of dynein in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 130: 687–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Asakawa K, Toh-e A 2002. Mitotic exit network controls the localization of Cdc14 to the spindle pole body in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Biol 12: 944–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W 1998. Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science 282: 1721–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]