Members of the Flamingo cadherin family are required in a number of different in vivo contexts of neural development, including growth control of dendrites, axonal navigation, tract formation, and target selection. The authors demonstrate that Esn binds to the carboxyl cytoplasmic tail (C-tail) of Fmi and that this binding was critical for dendritic self-avoidance.

Keywords: dendrite, avoidance, Flamingo, cadherin superfamily, LIM domain

Abstract

Members of the Flamingo cadherin family are required in a number of different in vivo contexts of neural development. Even so, molecular identities downstream from the family have been poorly understood. Here we show that a LIM domain protein, Espinas (Esn), binds to an intracellular juxtamembrane domain of Flamingo (Fmi), and that this Fmi–Esn interplay elicits repulsion between dendritic branches of Drosophila sensory neurons. In wild-type larvae, branches of the same class IV dendritic arborization neuron achieve efficient coverage of its two-dimensional receptive field with minimum overlap with each other. However, this self-avoidance was disrupted in a fmi hypomorphic mutant, in an esn knockout homozygote, and in the fmi/esn trans-heterozygote. A functional fusion protein, Fmi:3eGFP, was localized at most of the branch tips, and in a heterologous system, assembly of Esn at cell contact sites required its LIM domain and Fmi. We further show that genes controlling epithelial planar cell polarity (PCP), such as Van Gogh (Vang) and RhoA, are also necessary for the self-avoidance, and that fmi genetically interacts with these loci. On the basis of these and other results, we propose that the Fmi–Esn complex, together with the PCP regulators and the Tricornered (Trc) signaling pathway, executes the repulsive interaction between isoneuronal dendritic branches.

Neurons receive sensory or synaptic inputs that strike on their dendrites. Different types of neurons elaborate cell type-specific dendritic arbors, and these highly variable shapes contribute to differential processing and integration of the inputs by individual neuronal types (London and Hausser 2005; Stepanyants and Chklovskii 2005; Jan and Jan 2010). Among those shapes, the “space-filling” type is the one that uniformly covers its two-dimensional receptive field (Fiala and Harris 1999). Close inspection of space-filling arbors, such as those of retinal ganglion cells, reveals two categories of avoidance behaviors of dendritic branches (Wassle et al. 1981): Dendrites of the same cell hardly overlap with each other (self-avoidance or isoneuronal avoidance) (Grueber and Sagasti 2010), and branches of adjacent neurons of the same type innervate a field in a complete, but minimally overlapping, manner (tiling). These crossing-proof behaviors facilitate orderly projection of inputs for efficient and unambiguous signal processing (Zipursky and Sanes 2010).

Studies on cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the space filling have been pioneered by model systems including dendritic arborization (da) neurons in Drosophila larvae. These neurons are classified into classes I–IV, in order of increasing size of their receptive fields and/or arbor complexity at the mature larval stage, and it is class IV neurons that develop the most complicated and expansive arbors with space-filling capability, whereas class I neurons generate sparse comb-like arbors (Grueber et al. 2002). Results of cell biological and genetic experiments support the hypothesis that repulsive interactions between dendritic branches play an essential role in self-avoidance and tiling (Grueber et al. 2002; Sugimura et al. 2003). It has been posited that contact and repulsion occurs between encountering isoneuronal terminal branches, although an alternative repulsive mechanism via an extracellular diffusible substance is not excluded (Zinn 2004; Shimono et al. 2010). Self-avoidance and tiling require the NDR family kinase Tricornered (Trc)/Sax-1, the upstream Ste-20 family kinase Hippo (Hpo), and Furry (Fry)/Sax-2, which is an activator of Trc (Emoto et al. 2004, 2006; Gallegos and Bargmann 2004); however, their upstream components, including a cell surface receptor, have not been identified.

Studies in different directions have revealed that two families of cell surface recognition molecules underlie dendrite self-avoidance, but not tiling. One is the Dscam immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) in Drosophila and mice (Hughes et al. 2007; Matthews et al. 2007; Soba et al. 2007; Fuerst et al. 2008, 2009), and the other is Turtle (Tutl) of the Dasm1 IgSF in Drosophila (Long et al. 2009). Relevant signaling molecules downstream from either Dscam1 or Tutl have not been found, and there is as yet no evidence for a functional relationship between Trc and Dscam1 or Tutl (Matthews et al. 2007; Soba et al. 2007; Long et al. 2009).

Here we report that self-avoidance of class IV da neurons requires a novel complex of a cell surface protein and a previously uncharacterized protein: a Drosophila atypical cadherin, Flamingo (Fmi; also designated Starry night) (Chae et al. 1999; Usui et al. 1999), which had been originally discovered in studies on epithelial planar cell polarity (PCP), and a LIM domain protein, Espinas (Esn), respectively. Fmi belongs to the evolutionarily conserved family of seven-pass transmembrane cadherins and comprises the ectodomain (including cadherin repeats), the seven-pass transmembrane domain, and the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (C-tail) (Fig. 1A). In vivo roles of the Fmi family members have been reported in a number of different contexts of neural development in several animal models (Takeichi 2007; Jan and Jan 2010). These include growth control of dendrites in Drosophila and mammals (Gao et al. 2000; Sweeney et al. 2002; Reuter et al. 2003; Shima et al. 2004, 2007; Kimura et al. 2006), target selection of Drosophila photoreceptor axons (Lee et al. 2003; Senti et al. 2003; Chen and Clandinin 2008; Hakeda-Suzuki et al. 2011), axonal navigation and tract formation in mouse brains or Caenorhabditis elegans (Tissir et al. 2005; Zhou et al. 2008; Steimel et al. 2010), and restriction of a migrating trajectory of motor neurons in zebrafish (Wada et al. 2006; Wada and Okamoto 2009). In spite of all of these and other studies, downstream molecules of these Fmi family members have been poorly understood in neurons, except for indirect connections of mammalian homologs Celsr2 and Celsr3 to trimeric G proteins (Shima et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Flamingo is required cell-autonomously to repress dendritic crossing. (A) Domain organization, an amino acid substitution in fmiE86, and two isoforms of Fmi. (E) EGF-like repeat; (G) Laminin A globular domain; (R) hormone receptor domain; (P) Latrophilin/CL-1-like GPS domain; (JM-A) the N-terminal half of the juxtamembrane region (see details in Fig. 2A). Two isoforms, FmiTTV (total 3579 amino acids in length) and FmiAEY (3574 residues), are distinct only at their C termini (Chae et al. 1999; Usui et al. 1999, respectively). (B–F,B′–F′) Live images of dendritic arbors of class IV ddaC. Boxed regions in B–F are magnified in B′–F′. The wild type (B ,B′), fmiE86/fmiE59 (C,C′), and fmiE86/fmiE59 that express FmiTTV (fmiE86/fmiE59 + FmiTTV) (D,D′), FmiAEY (fmiE86/fmiE59 + FmiAEY) (E,E′), or FmiTTVΔJM-A (fmiE86/fmiE59 + FmiTTVΔJM-A) (F,F′) in class IV neurons. Anterior is left and dorsal is up in this and all subsequent pictures, unless described otherwise. Arrows indicate crossings of dendritic branches. Genotypes are as follows: +/+; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (B ,B′), fmiE86/Gal44-77 fmiE59; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (C,C′), fmiE86/Gal44-77 fmiE59; UAS-FmiTTV ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (D,D′), fmiE86/Gal44-77 fmiE59; UAS-FmiAEY ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (E,E′), and fmiE86/Gal44-77 fmiE59; UAS-FmiTTVΔJM-A ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (F,F′). Bars: B–F, 50 μm; B′–F′, 20 μm. (G,H) Quantitative analyses of the sum of branch lengths in each imaged zone (G; see details in the Materials and Methods) and the crossing index (H) of ddaC neurons of indicated genotypes. The crossing phenotype of the fmi mutant was significantly recovered when either FmiTTV or FmiAEY was expressed in ddaC. Error bars indicate the mean ± SD; (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01; (***) P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA and HSD post hoc test). Black asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from the wild type, and blue asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from the fmi hypomorph. (NS) Statistically not significant (P > 0.05). The number of cells counted for each genotype is indicated in G.

In this study, we show that Esn binds to the C-tail of Fmi and that this binding is critical for dendritic self-avoidance. Intrigued by the fact that Fmi and Prickle (Pk), a close cognate of Esn, are core group members of the PCP pathway (Usui et al. 1999; Tree et al. 2002), we investigated whether other PCP regulators participate in self-avoidance. We found that PCP genes such as Van Gogh (Vang) and frizzled (fz) are also necessary for the avoidance, and that fmi genetically interacts with these loci. We discuss the hypothesis that the Fmi–Esn complex, together with these PCP regulators and the Hpo–Trc cascade, plays a pivotal role at contact sites of dendritic branches in homotypic repulsion.

Results

Fmi is required for self-avoidance of dendritic branches of class IV da neurons

In our initial study of flamingo (fmi), we isolated a collection of fmi alleles and characterized embryonic-lethal null alleles, such as fmiE59, at the nucleotide level (Usui et al. 1999). In addition to those strong alleles, we found a hypomorph, fmiE86. fmiE86/fmiE59 trans-heterozygotes survived until wandering third instar larval stages and even up to the adult stage. The fmiE86 missense mutation is within the ectodomain (Fig. 1A). In the mutant embryo, the level of FmiE86 protein did not appear to alter much in neurons, but the mutant protein lost its normally polarized subcellular localization in the pupal wing epidermis (see details in Supplemental Fig. S1).

When we observed dendritic arbors of class IV da neurons in the trans-heterozygotes, terminal branches within the same neurons frequently looked like they were crossing with each other (Fig. 1B–C′). This finding raised the possibility that the fmiE86/fmiE59larvae (designated as the fmi mutant hereafter) were defective in self-avoidance of dendritic branches. This phenotype was not seen in fmiE86/+ larvae (data not shown); thus, fmiE86was not a gain-of-function mutation. Throughout subsequent studies, we analyzed this phenotype and pursued the underlying mechanism by focusing on the most dorsal class IV neurons, ddaC, in wandering third instar larvae (unless described otherwise).

In previous studies where branch crossing of da neurons was investigated, Z-stack images of confocal sections were projected and used for quantitative analysis, but the distance between the crossing branches along the Z-axis was not necessarily discussed (but see Emoto et al. 2004). In the course of our analysis, we noticed that 15.9% ± 8.4% (SD) of “crosses” in the projected images of the wild-type neurons (n = 10) were in fact overpasses according to our classification (see details in the Materials and Methods). Because the overpass is suspected to be a consequence of overgrowth of terminal branches, not necessarily due to a defect in self-avoidance, we distinguished crossing from overpass in this study. The crossing in the fmi mutant appeared to occur mostly between terminal branches. We then measured the cumulative length of dendritic branches and the number of branch crossings in each arbor and calculated the crossing index (Fig. 1G,H). Within the dorsal region of the arbor examined (Fig. 1), the crossing index of the fmi mutant showed a fourfold increase compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 1H). It appeared unlikely that this excessive crossing was secondary to dendrite overgrowth, as shown by the fact that the cumulative branch length in the mutant was not significantly altered (Fig. 1G). Thus, Fmi regulates the self-avoidance of primarily terminal branches of class IV dendrites.

IgSF members Dscam1 and Turtle (Tutl) are also required for self-avoidance of da neurons (Hughes et al. 2007; Matthews et al. 2007; Soba et al. 2007; Long et al. 2009). Loss of Dscam1 function leads not only to crossing, but also to bundling of branches, which we rarely found in fmi mutants. In contrast to the defect in self-avoidance, homotypic repulsion between neighboring dendrites of class IV neurons (tiling) was not impaired in fmi mutants, and it was not in Dscam1 or tutl mutants, either. Class I neurons in dscam1 and tutl displayed significant crossing and extensive bundling. These neurons in the fmi mutant elaborate normal arbors with the typical comb-like shape (data not shown).

The role of Fmi in self-avoidance is cell-autonomous

To clarify whether fmi is autonomously required in class IV neurons for dendritic self-avoidance, we designed class IV neuron-specific rescue experiments. As reported previously, the fmi locus is expressed in a dimorphic manner: Alternate splicing of exons encoding the C terminus gives rise to two protein isoforms (Chae et al. 1999; Usui et al. 1999), which we designate as FmiTTV and FmiAEY in this study (Fig. 1A). When each isoform was expressed in class IV neurons in the mutant, the number of crossings was decreased and the index was restored to the wild-type level (Fig. 1C–E′,H). The cumulative length of branches within the area examined was not altered in the mutant neuron that expressed FmiTTV or FmiAEY when compared with that in the wild type or fmi mutant. These results suggest that fmi regulates dendritic self-avoidance of class IV da neurons in a cell-autonomous fashion.

Although several groups including our own have studied phenotypes of fmi mutant da neurons by using strong alleles, the dendrite crossing phenotype has not been reported before (Gao et al. 2000; Grueber et al. 2002; Sweeney et al. 2002; Kimura et al. 2006). We generated MARCM clones of the null allele fmiE59, re-examined whether they displayed the crossing phenotype, and did not find obvious crossings of dendritic branches (Supplemental Fig. S5). The class IV neurons in the fmiE86/fmiE59 larvae displayed not only the dendrite crossing phenotype, but also occasional axon misrouting and stalling of growth cones (data not shown). These axonal phenotypes are reminiscent of those of the null mutant clone (Sweeney et al. 2002). These observations raise the possibility that a perdurance effect in the MARCM clone (residual mRNA and/or protein molecules from the precursor cell) may have masked the crossing, although it was not sufficient for the axon guidance. To minimize the hypothetical mRNA carryover in the clones, we expressed fmi dsRNA in a fmi-null MARCM clone. We had already shown that the expression of this dsRNA was highly effective in knocking down fmi mRNA in imaginal epithelial tissues (Fig. 3C, below). Even with this “fmi RNAi in fmi MARCM” combination, the neurons did not show an obvious crossing defect. We interpreted this result as follows: RNAi may not be effective enough in the neurons because the dsRNA expression in the wild-type background neurons did not reproduce the axonal phenotype of the fmi mutant (data not shown), and/or the persistence of residual Fmi proteins was long enough to mask the crossing phenotype.

Figure 3.

LIM domain-dependent and Fmi-dependent localization of Esn at apical cell contact sites in wing epithelia. Either Flag-tagged Esn (full length) or tagged EsnΔLIM (ΔLIM) was expressed by using ptc-Gal4 driver, and 30–31 h APF (after puparium formation) wings were double-stained for the tag (6Flag:Esn) (A–C; green in A″–C″) and endogenous Fmi (A′–C′; magenta in A″–C″). (A″–C″) Merged images. (A–B″) Wild-type background. (C–C″) fmi knocked-down background. Yellow dots indicate cells that were immediately adjacent to the posterior border of the ptc-Gal4 domain. Genotypes are as follows: ptc-Gal4/+; UAS-6Flag:EsnFL/+ (A–A″), ptc-Gal4/+; UAS-6Flag: EsnΔLIM/+ (B–B″), and ptc-Gal4/UAS-fmiRNAi; UAS-6Flag:EsnFL/UAS-fmiRNAi (C–C″). Bar, 10 μm. Distal is to the right and anterior is at the top.

We next addressed whether one subdomain in the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail, which we designated “juxtamembrane domain A” (JM-A in Fig. 1A), was important for the cell-autonomous role of Fmi or not. We showed that a mutant form of FmiTTV lacking JM-A (FmiΔJM-A) was unable to rescue the self-avoidance defect of the fmi mutant (Fig. 1F,F′); rather, the crossing index significantly increased compared with that of the mutant (Fig. 1H). This result showed that JM-A was necessary for Fmi function, and also suggested that FmiΔJM-A exerted a dominant-negative effect on endogenous FmiE86 protein.

A PET-LIM protein Espinas (Esn) binds to the C-tail of Fmi

To explore molecular mechanisms whereby Fmi regulates neuronal and epithelial cell morphogenesis, we and other groups have performed structure–functional analyses of Fmi or its homologs in other species (Shima et al. 2004, 2007; Kimura et al. 2006; Strutt and Strutt 2008; Steimel et al. 2010). These studies suggest the importance of the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail (C-tail in Fig. 2A) in controlling the cytoskeleton and/or endocytosis. The C-tail contains a juxtamembrane domain where amino acid sequences are conserved across species (JM in Fig. 2A,B), and we used it as bait to hunt for binding partners to identify potential signaling components downstream from Fmi.

Figure 2.

Identification of PET-LIM domain protein Espinas (Esn) as a Fmi C-tail-binding partner. (A) Schematic representation that highlights the membrane-proximal portion of the Fmi ectodomain, the seven-pass transmembrane domain, and the C terminus of FmiTTV (C-tail). The juxtamembrane region in the C-tail was subdivided into the N-terminal half (JM-A) and the C-terminal half (JM-B). See domains R and P in the legend for Figure 1A. Numbers are those of amino acid residues in FmiTTV. (B) A multiple alignment of amino acid sequences of the JM regions of four Fmi orthologs. (Dm) Drosophila melanogaster [AAF58763.5]; (Tc) Tribolium castaneum [XP_968232.1]; (Is) Ixodes scapularis [ISCW022151-PA]; (Hs CELSR1) Homo sapiens [NP_055061.1]. Asterisks and red letters indicate residues identical throughout the four species, whereas green letters are similar ones. (C) Espinas (Esn) contains a PET domain (PET), triple LIM domains (LIM), and a CAAX motif at the C terminus. Its estimated molecular weight is 86,600. (D–F) Fmi–Esn interaction was supported by a yeast two-hybrid assay (D) and coimmunoprecipitation (E,F). (D) Proteins of the following pairs were expressed in yeast: a fusion of Gal4-DNA-binding domain (DB) to Fmi JM and a mock Gal4 transcription-activating domain (AD) as a negative control (DB-Fmi[JM] + AD-empty), DB-Fmi[JM] and a fusion of AD to the LIM domain of Esn (DB-Fmi[JM] + AD-Esn[LIM]), or a fusion of DB to lamin and AD-Esn[LIM] as another negative control (DB-Lamin + AD-Esn[LIM]). Only cells of DB-Fmi[JM] + AD-Esn[LIM] grew under a selective condition (−adenine, −histidine). (E) Flag-tagged JM of Fmi and Myc-tagged LIM of Esn were coexpressed in S2 cells. The cell lysates were blotted with anti-Flag (Fmi input) or anti-Myc (Esn input). Flag-tagged JM was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag and blotted with either anti-Myc (Esn co-IP) or anti-Flag (Fmi IP). (F) Tissue lysates were made from wild-type (y w) larval CNS complexes. Lysates were blotted with anti-Fmi or anti-Esn (input). For co-IP, the lysates were incubated with either anti-Fmi or normal rat serum, and immunoprecipitated proteins were blotted with either anti-Fmi or anti-Esn. [Fmi (FL)] Fmi full-length protein; [Fmi (ecto)] Fmi ectodomain that is made by processing of endogenous Fmi (Usui et al. 1999).

Our yeast two-hybrid screening highlighted members of the Drosophila PET-LIM domain family: Prickle (Pk), Espinas (Esn), and Testin (Gubb et al. 1999). Pk has been well studied as one of the core group members of PCP, whereas any physiological roles of Esn were unknown. Because of prominent expression of esn in the nervous system (described below), we considered Esn to be a strong candidate for a Fmi binder in neurons and analyzed this protein further. The JM domain of Fmi interacted with the LIM domain of Esn or Pk in a targeted yeast two-hybrid assay (Esn: Fig. 2D; Pk: data not shown) and also in a coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment using Drosophila S2 cells (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S2B). We dissected JM and showed that the N-terminal subdomain (JM-A in Fig. 2A,B) bound to LIM much more strongly than the C-terminal JM-B (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S2B). Although the detection of the JM–LIM interaction was straightforward, we were unable to detect a Fmi–Esn interaction by co-IP when both full-length proteins were expressed in S2 cells (data not shown). We anticipated a technical difficulty with the demonstration of the Fmi–Esn interaction by co-IP, considering that Fmi is a multipass transmembrane protein of 3579 residues. Nonetheless, we attempted to demonstrate the physical interaction between the endogenous proteins by using a larval CNS lysate as a source material. In two out of two co-IP experiments, we did detect endogenous Esn in the anti-Fmi immunoprecipitates, but not in the immunoprecipitates with negative control antibodies, although the efficiency of Esn co-IP with Fmi was low (Fig. 2F). These results imply that the association of Esn to Fmi might be transient and/or dependent on the cellular milieu (see the Discussion).

The Fmi–Esn interaction was further investigated in a cell adhesion assay (Supplemental Fig. S3). Fmi-expressing S2 cells adhere to each other due to Fmi–Fmi homophilic interactions, and Fmi often accumulates at sites of cell–cell contacts (Usui et al. 1999; Kimura et al. 2006). We applied this assay to test whether Esn was colocalized with Fmi at the cell contact sites; however, we could not draw clear conclusions (see details in the legend for Supplemental Fig. S3). As an alternative approach to assess the possibility of Fmi–Esn colocalization in cells, we used pupal wing epithelia where endogenous Fmi is enriched at cell boundaries (Fig. 3). When Esn was ectopically expressed in the wing, it was colocalized with Fmi at cell boundaries (Fig. 3A–3A″). In contrast, an Esn mutant form that lacked the LIM domain (EsnΔLIM) was diffusely distributed in the cells and did not exhibit obvious concentration at the boundaries where Fmi was accumulated (Fig. 3B–B″). Furthermore, the full-length Esn was no longer localized at the apical cell contact sites when fmi was knocked down (Fig. 3C–C″). These results show that Esn can be localized at cell contact sites in a LIM domain- and Fmi-dependent manner.

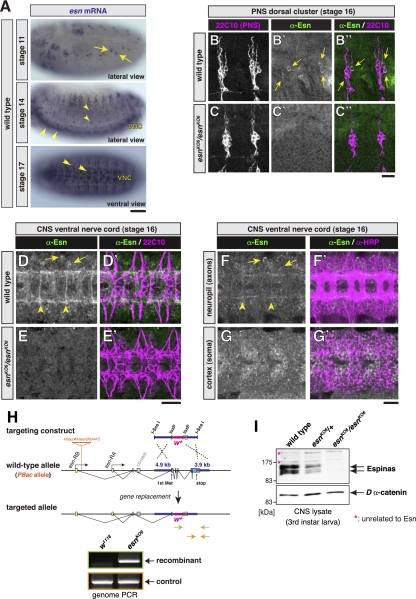

Esn is expressed in the nervous system

We examined expression patterns of three members of the Drosophila PET-LIM domain family by using in situ hybridization of embryos and found that only esn was strongly expressed in the nervous system (Fig. 4A). pk was expressed in the epidermis, whereas testin transcripts were hardly seen anywhere (Gubb et al. 1999; our data not shown). esn transcripts were detected in sensory organ precursors (SOPs) and also in subsets of neurons in the peripheral nervous system and the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 4A). Our antibodies to Esn labeled embryonic SOPs (data not shown) and small subpopulations of sensory neurons in the peripheral nervous system (Fig. 4B–B″); in the ventral nerve cord, the pattern of labeled axon fascicles (Fig. 4D,D′) and cell bodies (Fig. 4G,G′) matched esn mRNA-positive cells (bottom of Fig. 4A). Because immunoreactivity of our antibody was not seen in esn knockout embryos (Fig. 4C–C″,E,E′), the signals in the wild type represented those of endogenous Esn proteins (the esn knockout is described below). The Esn-expressing axon fascicles in the ventral nerve cord were located in posterior commissures (arrowheads in Fig. 4D,D′,F,F′) and most laterally in longitudinal connectives (arrowheads in Fig. 4F,F′).

Figure 4.

esn expression in the nervous system and generation of an esn knockout allele. (A) In situ hybridization of embryos with an esn antisense RNA probe. (Top) SOPs (arrows) at stage 11. (Middle) A subset of sensory neurons (arrowheads) and many cells within the ventral nerve cord (VNC; double arrowheads) at stage 14. (Bottom) esn-expressing cells in the ventral nerve cord (VNC) at stage 17 (arrowheads). A sense probe gave a low background (data not shown). Bar, 80 μm. (B–G′) Stage 16 embryos that were double-labeled either for a pan sensory neuron marker (22C10) and Esn (B–E′) or for a pan neuronal marker (anti-HRP) and Esn (F–G′). Images of dorsal clusters in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) (B–C″) and those of the ventral nerve cord in the CNS (D–G′). (B–C″) Signals were detected in two neurons per dorsal cluster in the wild type (arrows in B′,B″), whereas they were not detected in an embryo homozygous for esnKO6 (C′; described below). The number and morphology of 22C10-positive sensory neurons appeared to be normal in esnKO6 mutant embryos. Bar, 20 μm. (D–E′) Ventral nerve cords of the wild type (D,D′) and the esnKO6 mutant (E,E′). Esn proteins were distributed along a small subset of axon bundles, including posterior commissures (arrowheads) and a small number of cell bodies (arrows). (E,E′) Both classes of signals were lost in the knockout. (D′,E′) No dramatic morphological defect was found in the 22C10-positive axon scaffold. (F–F′) Esn-positive longitudinal connectives were located at the lateral side of the axon scaffold (arrowheads). (G–G′) Cell bodies of Esn-positive neurons in the ventral nerve cord. Bar, 20 μm. (H) Homologous recombination scheme to knock out the esn locus. w+ indicates the white gene, which was used as a marker to discriminate recombinants. Light-blue boxes represent coding sequences, and flanking dark-blue lines indicate genomic DNA that was used for the targeting. The esn locus has two transcription initiation sites: esn-RA and esn-RB. PBac{WH}esn[f00447] indicates a piggyBac insertion site (Thibault et al. 2004). (Bottom) The targeting event was verified by genomic PCR. (w1118) Host strain; (esnKO6) one of targeted lines. Green arrows indicate primers to distinguish the recombinant from nonrecombinants, whereas orange arrows are control primers. (I) Detection of endogenous Esn protein. Western blot analysis of larval CNS of yw (wild type), esn heterozygotes (esnKO6/+), and esn homozygotes (esnKO6/esnKO6) for Esn and for Dα-catenin as a loading control. It was unknown whether multiple bands of endogenous Esn represent degraded forms or modified ones. Asterisks mark bands of proteins unrelated to Esn. The amount of protein in each lane was equivalent to 2.5 larvae.

We attempted to identify Esn-positive sensory neurons in the dorsal cluster in the embryo (arrows in Fig. 4B′,B″). In >50 abdominal hemisegments observed, almost all dorsal clusters had labeled neurons that were always located at the most posterior location, which allowed us to conclude that those neurons were class I ddaEs (Grueber et al. 2002). Apart from ddaE, Esn signals in other neurons were only marginal, and the number and the position of those in the clusters looked variable. Although we addressed whether any of those weakly labeled cells were also positive for a class IV-selective marker, Knot/Collier (Hattori et al. 2007; Jinushi-Nakao et al. 2007; Crozatier and Vincent 2008), it was difficult to conclude that Knot/Collier-positive class IV neurons were always positive for Esn (data not shown). At the limit of our detection, we did not observe anti-Esn or anti-Fmi immunoreactivity in sensory neurons in wandering third instar larvae (data not shown).

Esn in the neuron is an essential component of dendritic self-avoidance

To gain insight into an in vivo role of esn, we looked for loss-of-function mutations. Although one transposon insertion allele was available (Fig. 4H; Thibault et al. 2004), we found it to be a hypomorph, as shown by the fact that the level of Esn protein was reduced by approximately half (data not shown), so we did not characterize it further. To study a complete loss-of-function phenotype, we knocked out esn by the conventional homologous recombination method (Rong and Golic 2000; Millard et al. 2007) and isolated a protein-null mutation esnKO6 (Fig. 4H,I). Homozygous esnKO6 animals were viable and fertile, and did not display obvious defects in PCP in the wing and the notum or in morphology of the compound eye.

To address whether homozygous esnKO6 animals developed class IV dendritic arbors normally, we employed the same class IV marker with which we found the defect in self-avoidance in the fmi mutant (Fig. 5). esnKO6 homozygotes also showed abnormal crossing of dendritic branches with no significant change in the total length (Fig. 5A–5B′,F,G). Class IV-specific expression of Esn in the knockout animal resulted in complete recovery of the crossing (Fig. 5C,C′,G); on the other hand, the defect was not restored to normal by expressing EsnΔLIM (Fig. 5D,D′,G). Furthermore, we examined the effect of esn knockdown by class IV-specific expression of an esn-specific dsRNA. To effectively suppress the level of esn mRNA, esn dsRNA was expressed in an esnKO6/+ heterozygous background. The esn RNAi animals displayed the crossing defect (Fig. 5E,5E′,I,J). All of these results are consistent with the hypothesis that the Fmi–Esn interaction in the class IV neuron controls the self-avoidance of branches in a cell-autonomous manner, and that this interaction is mediated by the LIM domain of Esn and the JM domain of Fmi. Although expression of Esn was clearly detected in the class I neuron ddaE in the wild-type embryo (Fig. 4B,B′), we did not see gross morphological defects of ddaE arbors in esnKO6 homozygous larvae (data not shown). As far as class I and IV da neurons were concerned, we did not notice axonal misrouting or premature termination in the periphery.

Figure 5.

Espinas is required cell-autonomously to repress dendritic crossing. (A–D′) Live images of dendritic arbors of class IV ddaC. Boxed regions in A–D are magnified in A′–D′. The wild type (A,A′), esnKO6/esnKO6 (B,B′), esnKO6/esnKO6 that expressed full-length Esn (esnKO6/esnKO6 + EsnFL) (C,C′) or Esn lacking LIM (esnKO6/esnKO6 + EsnΔLIM) (D,D′) in ddaC. Arrows indicate crossings of dendritic branches. Genotypes are as follows: +; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (A,A′), esnKO6/Gal44-77 esnKO6; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (B,B′), esnKO6/Gal44-77 esnKO6; UAS-mCherry:EsnFL ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (C,C′), esnKO6/Gal44-77 esnKO6; UAS-mCherry:EsnΔLIM ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (D,D′), and +/Gal44-77 esnKO6; UAS-esnRNAi ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (E,E′). Bars: A–E, 50 μm; A′–E′, 20 μm. (F,G) Quantitative analyses of two parameters of the dendritic arbor of ddaC: the sum of branch lengths in each imaged zone (F) and the crossing index (G). The elevated crossing phenotype of the esn mutant was recovered by EsnFL expression, whereas EsnΔLIM expression did not sufficiently suppress crossing defect. Error bars indicate the mean ± SD; (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01; (***) P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA and HSD post hoc test). Black asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from the wild type, and blue asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from esnKO6/esnKO6. (NS) Statistically not significant (P > 0.05). The number of cells counted for each genotype is indicated in F. (H) Expression of EsnFL or EsnΔLIM in mutant backgrounds. Western blot analysis of larval CNS of the wild type with no transgene (no Tg), and esnKO6 homozygotes (KO6/KO6) that expressed either mCherry:EsnFL or mCherry:EsnΔLIM, probed with anti-Esn and anti-Dα-catenin as a loading control. The amount of protein in each lane was equivalent to 1.75 larvae. Genotypes are as follows: y w (no Tg), esnKO6/Gal44-77 esnKO6; UAS-mCherry:EsnFL ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (FL), and esnKO6/Gal44-77 esnKO6; UAS-mCherry:EsnΔLIM ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (ΔLIM). (I,J) Quantitative analyses of two parameters of the dendritic arbors of ddaCs of the wild type (genotype as in A) and the esn knockdown (genotype as in E): the sum of branch lengths in each imaged zone (I) and the crossing index (J). The crossing index was elevated in the esn dsRNA-expressing ddaC neurons. The number of cells counted for each genotype is indicated in I.

Although pk and testin were not strongly expressed in the da sensory neurons, as evidenced by our in situ hybridization experiments, we examined whether pk plays any role in the dendritic self-avoidance process. pk-null mutants showed no crossing defect (Supplemental Fig. S2C–F). Because no testin-null mutation was available, the contribution of Testin to neural development remains unclear.

fmi, esn, and other genes cooperatively control dendritic self-avoidance

In previous studies of dendrite morphogenesis of da neurons, functional connections between molecules were often reflected by defective phenotypes in trans-heterozygous combinations of mutations of the relevant genes (e.g., Emoto et al. 2004, 2006). We also employed this genetic interaction approach to address the biological relevance of the Fmi–Esn physical interaction and found a positive result (Fig. 6). The trans-heterozygous combination of fmi- and esn-null mutations (fmiE59/esnKO6) exhibited a marked defect in self-avoidance (Fig. 6A–C,E,J), which was as severe as the phenotype in the fmi hypomorphic mutant (Fig. 1H).

Figure 6.

Analysis of genetic interactions among fmi, esn, RhoA, Van Gogh (Vang), tricornered (trc), and furry (fry). (A–I) Live images of dendritic arbors of class IV neuron ddaC in transheterozygous mutants of fmi, esn, RhoA, Van Gogh (Vang), trc, and furry (fry). Genotypes tested are indicated in individual panels, except for two copies of a marker gene, ppk-eGFP. Bar, 50 μm. Arrows indicate crossings of dendritic branches. Genotypes are as follows: +/+; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (A), fmiE59/+; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (B), esnKO6/+; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (C), RhoAE3.10/+; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (D), fmiE59/esnKO6; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (E), fmiE59/RhoAE3.10; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (F), Vangstbm6/ Vangstbm6; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (G), Vangstbm6/ fry1; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (H), and fmiE59/ fry1; ppk-eGFP/ppk-eGFP (I). (J) Quantitative analyses of the crossing index. Error bars indicate the mean ± SD; (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01; (***) P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post hoc test). Magenta asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from the wild type, and blue asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of the cohort from the corresponding heterozygous controls. (NS) Statistically not significant (P > 0.05). The number of cells counted for each genotype is indicated in J.

We expanded our search for genetic interactions in two directions. First, we investigated the effects of mutations in PCP genes besides fmi on dendrite morphogenesis, partly because both Fmi and Prickle (Pk), a close cognate of Esn, are essential components of PCP (Usui et al. 1999; Tree et al. 2002), and partly because associations of Fmi or a vertebrate homolog, Celsr1, with other PCP proteins have been reported (Chen et al. 2008; Devenport and Fuchs 2008). Specifically we explored (1) whether any strong or null mutations of PCP genes showed genetic interactions with fmiE59 and (2) whether any of those mutations caused the crossing phenotype in homozygotes when they survived until a mature larval stage. The PCP genes tested included Van Gogh (Vang; also designated strabismus), fz, RhoA, dishevelled (dsh), and pk (Krasnow et al. 1995; Strutt et al. 1997; Wolff and Rubin 1998; Gubb et al. 1999). We found statistically significant defects in self-avoidance in fmi/RhoA trans-heterozygotes, Vang homozygotes, fmi/Vang trans-heterozygotes (Fig. 6F,G,J), and fz homozygotes (Supplemental Fig. S4). The crossing phenotype was also seen in the wild type when dominant-negative RhoA was expressed in class IV da neurons (Supplemental Fig. S4). In dsh1 homozygotes, the number of branches was obviously decreased, and we did not quantify dendrite crossing (data not shown).

Second, we investigated whether fmi or Vang interacted with tricornered (trc) and hippo (hpo), which encode protein kinases, or with furry (fry), encoding a positive cofactor of Trc, following this reasoning: Although it has been shown that the Hpo–Trc kinase cascade is required for dendrite self-avoidance and tiling selectively in class IV neurons (Emoto et al. 2004, 2006; Soba et al. 2007), its upstream components, including a cell surface receptor, have not been identified. We suspected that Fmi could be connected with the cascade at least in the context of self-avoidance. We first confirmed the crossing defect in trc or fry homozygous mutants by using our quantitative protocol, and then detected the elevated crossing phenotype in trans-heterozygous combinations of Vang/fry, fmi/fry, fmi/trc (Fig. 6H–J), and fmi/hpo (Supplemental Fig. S4).

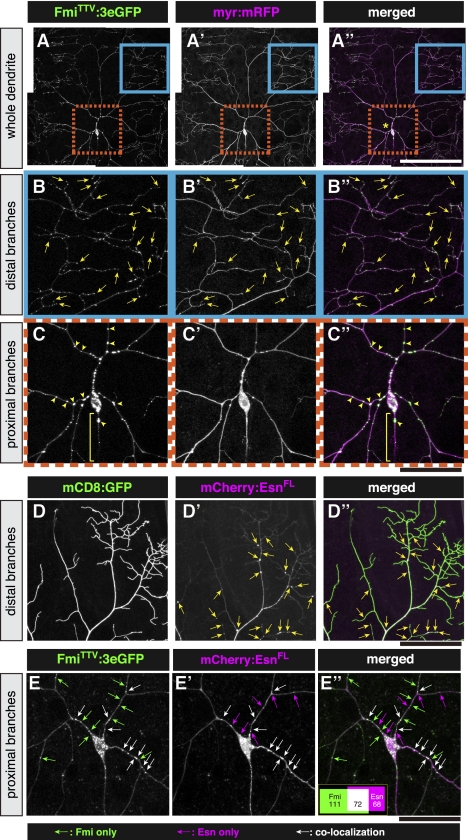

Fmi:3eGFP and mCherry:Esn are partly colocalized in dendrites

Assuming that our hypothesis about the role of the Fmi–Esn complex in self-avoidance is correct, how do these molecules suppress dendrite crossing in class IV da neurons? One scenario would be that the complex is present in branches, and Fmi–Fmi homophilic (but transient) interaction takes place at the interface between branches, the signal for which is mediated by Esn, resulting in retraction and/or turning away of the encountered branches. To verify this hypothesis, we studied the subcellular localization of Fmi:3eGFP and mCherry:Esn in da neurons (Fig. 7). We verified that each fusion protein was able to rescue the crossing phenotype in each respective mutant (Fig. 5; data of Fmi:3eGFP not shown) and that Fmi:3eGFP rescued both lethality and the PCP phenotype of the fmi-null mutant as well (Harumoto et al. 2010).

Figure 7.

Distributions of fluorescent protein-tagged Fmi or Esn in dendrites of class IV da neurons. (A– C″) FmiTTV:3eGFP (A–C; green in A″–C″) in ddaC. Membrane-targeted mRFP (myr-mRFP) (magenta in A″–C″) was coexpressed to visualize entire dendritic branches, including distal tips. B–B″ and C–C″ are higher magnifications of boxed areas in A–A″ (blue boxes and orange boxes, respectively). Yellow arrows in B–B″ mark GFP-positive puncta at the tips of terminal branches, and yellow arrowheads in C–C″ are those in the proximal region of the dendritic arbor. Brackets indicate axons. (D–D″) The distal area of a dendritic arbor that expressed mCD8:GFP (D; green in D″) and mCherry:EsnFL (D′; magenta in D″). Yellow arrows indicate puncta of mCherry:EsnFL. (E–E″) Colocalization of FmiTTV:3eGFP and mCherry:EsnFL was examined in the proximal area. Green arrows, magenta arrows, and white arrows indicate puncta of FmiTTV:3eGFP, those of mCherry:EsnFL, and those of double positives, respectively. Quantitative data of seven neurons is shown by the Venn diagram, where figures indicate the total puncta numbers of FmiTTV:3eGFP single positives (green), mCherry:EsnFL single positives (magenta), and double positives (white). Genotypes are as follows: Gal44-77 UAS-myr-mRFP/+; UAS-FmiTTV:3eGFP/+ (A–C″), Gal44-77 UAS-mCD8:GFP/Gal44-77 UAS-mCD8:GFP; UAS-mCherry:EsnFL/UAS-mCherry:EsnFL (D–D″), and Gal44-77/UAS-FmiTTV:3eGFP; UAS-mCherry:EsnFL/UAS-mCherry:EsnFL (E–E″). Bars: A–A″, 150 μm; B–C″, 50 μm; D–E″, 40 μm.

Fmi:3eGFP gave punctate signals in dendrites, axons, and cell bodies, which provided a contrast to a diffuse distribution of membrane-bound mRFP (Fig. 7A–C″). Within dendritic arbors, tips of terminal branches were frequently labeled by Fmi:3eGFP puncta (167 out of 198 tips observed) (yellow arrows in Fig. 7B–B″). Signals of mCherry:Esn also looked punctate in the proximal area of the arbor; however, distal branches were diffusely labeled with fewer puncta when compared with arbors of Fmi:3eGFP-expressing neurons (Fig. 7D–E″). We quantified the extent of colocalization of Fmi:3eGFP and mCherry:Esn in the proximal area (Fig. 7E–E″). About 40% of Fmi:3eGFP puncta were associated with mCherry:Esn puncta, and ∼50% of mCherry:Esn puncta were associated with those of Fmi:3eGFP (inset in Fig. 7E″). The presence of these double-positive puncta in the proximal area suggested that Fmi and Esn might form stable complexes and/or that both were colocalized on the same vesicles. In the distal region, the complex might arise only transiently upon contacts between branches (see the Discussion).

Discussion

The Fmi–Esn interplay

In this study, we showed both physical and genetic interactions between Fmi and Esn, and proposed a role of the Fmi–Esn interplay in contact-dependent repulsive signaling between isoneuronal dendritic branches of class IV da neurons. In addition to the binding of the LIM domain of Esn to the JM domain of Fmi, we showed in a heterologous system that Esn was colocalized with Fmi at cell contact sites in a LIM domain-dependent manner. The LIM domain is shared by a number of proteins and is recognized as a modular protein-binding interface (Kadrmas and Beckerle 2004). Esn belongs to the Drosophila PET-LIM domain family, where two other members are Pk and Testin. Curiously, in our S2 cell experiments, Fmi JM was efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with Esn LIM, but we were unable to detect complexes of full-length Fmi and Esn in our co-IP experiments using S2 cells. Nonetheless, we did detect the co-IP of endogenous Esn with Fmi from larval CNS, although the efficiency of the co-IP was low. These results raise the possibility that the binding of Esn to Fmi in da neurons might be under the control of a conformational change and/or post-translational modifications of Esn. In fact, it has been shown for human Testin (hTes) that its LIM domains mediate the intramolecular interaction (Zhong et al. 2009). More specifically, the C-terminal LIM interacts directly with N-terminal hTes sequences, and this intramolecular association seems to preclude the docking of partners such as α-actinin. Furthermore, there might be a regulation at the level of tethering Esn to the plasma membrane. The CAAX motif at the C terminus of Esn could be the target of such a regulation. Potential candidates that may be involved in such a hypothetical regulation of Esn would be PCP regulators such as Vang (discussed below).

Possibilities of functional interactions between Fmi–Esn and the Trc pathway

A group of key molecules play pivotal roles in dendrite self-avoidance. That said, the underlying mechanisms involving these molecules (the Hpo–Trc kinase cascade, Dscam1, Tutl, and the Fmi–Esn interplay) seem to be complex, as suggested by the fact that phenotypic analyses of these genes show similarities as well as differences in terms of class specificity and self-avoidance versus tiling. Moreover, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms is currently limited. For example, unknown are the identities of interbranch signals and their sensors that are connected to the Trc pathway. Genetic interactions have been sought between trc and Dscam1 or tutl, but positive results have not been obtained (Matthews et al. 2007; Soba et al. 2007; Long et al. 2009). We found an interaction between fmi and trc; between fmi and fry, which encodes an activator of Trc; and between fmi and hpo, an upstream kinase. These genetic interactions by themselves do not necessarily support the idea that Fmi acts in close proximity to Trc, Fry, or Hpo; analysis of the Fmi–Esn and Trc–Fry complexes, and verification of their cross-talk, are required at the molecular level.

Fmi works together with other PCP regulators in self-avoidance and in other cellular ‘avoidance’ contexts

Our search for genetic interactions was targeted toward PCP genes, and we found several positive results. It should be emphasized that PCP regulators play important roles not only in epithelial sheets, but also in rearranging cell populations (Simons and Mlodzik 2008; Vladar et al. 2009). In connection with the avoidance behavior of the dendrites, intriguing analogies are found in contact inhibition of locomotion of neural crest cells in Xenopus and in stereotyping a trajectory of migrating facial motor neurons in zebrafish (Carmona-Fontaine et al. 2008; Vladar et al. 2009; Wada and Okamoto 2009). Vertebrate homologs of Pk, Vang, and Dsh are required for neural crest cells to initiate sustained directional migration away from the contact with another neural crest cell, although roles of Fmi homologs were not examined in this system (Carmona-Fontaine et al. 2008). Importantly, the PCP regulators are localized at the site of cell contact, leading to activation of RhoA. In the context of migration of the motor neurons, homologs of Fmi and Fz act in the surrounding neuroepithelium to prevent the integration of the neurons into the neuroepithelium, thus restricting them to the correct path (Wada et al. 2006; Wada and Okamoto 2009). Although the mechanisms are unknown, homologs of Fmi and Fz are also proposed to act together in axonal navigation and tract formation in mouse forebrain and C. elegans nerve cord on the basis of similar mutant phenotypes (Zhou et al. 2008; Steimel et al. 2010).

Colocalization hypothesis of Fmi, Esn, and other PCP proteins at contact sites of dendritic branches

We consider it likely that Fmi, Esn, Vang, and Fz are localized closely within branches and activate RhoA locally upon contact with other isoneuronal branches, redirecting those branches away from one another. However, in contrast to prominent puncta of Fmi:eGFP at most of the tips, mCherry:Esn was not necessarily enriched there and distributed more diffusely inside branches. These differential distributions do not necessarily exclude our hypothesis. As for the Trc kinase and its activator, Fry, both physical and genetic interactions are substantiated, and yet, those two molecules show distinct features of subcellular localization in da neurons (Fang et al. 2010). In mammals, localization of Pk1, a mammalian member of the PET-LIM domain family, is regulated by degradation that depends on the interaction of E3 ubiquitin ligases with one of the other PCP regulators, Dvl2 (Narimatsu et al. 2009). It could be that the contact between isoneuronal branches may trigger the Fmi–Esn interaction locally, with subsequent stabilization of the bound Esn, which is otherwise degraded. Another, mutually nonexclusive possibility would be that the association/dissociation of Esn and Fmi may be coupled to a switch of Esn signaling activity. There could be a third intriguing possibility: Esn may play a role in the trafficking of Fmi, such as promotion of endocytic recycling of Fmi. It has been proposed that Fmi is subject to high rates of endocytic turnover in the pupal wing (Strutt and Strutt 2008; Strutt et al. 2011), and a cytoplasmic motif of a mouse homolog of Fmi, Celsr1, governs its internalization (Devenport et al. 2011).

If the PCP proteins are localized at contact sites at least transiently, then how do they assemble on both sides of the interface? The assembly of the PCP proteins at cell boundaries has been best studied in the Drosophila wing epithelia, where the arrangement of the proteins is asymmetrical across proximodistal (P/D) cell boundaries: Vang and Pk at the proximal cell cortex, Fz and Dsh at the distal cortex, and Fmi at both (Usui et al. 1999; Simons and Mlodzik 2008; Vladar et al. 2009). In the dendritic arbor of a single da neuron, would it be possible that some terminal branches are Vang-rich “proximal” types, whereas others are Fz-rich “distal” ones? Alternatively, a single terminal branch or even a single tip could be a mosaic of Vang-rich and Fz-rich membrane domains. Coexpression of Fz and Vang with distinct tags in the same neuron and tracking pairs of terminal branches that are approaching each other at high-enough resolution may answer this question.

Materials and methods

Drosophila strains

We used pickpocket (ppk)-eGFP to visualize dendrites of class IV da neurons (Grueber et al. 2003) and Gal44-77 for forced expression of Fmi or Esn wild-type or mutant forms in class IV da neurons (Emoto et al. 2004). Alleles of fmi employed were nonsense-null fmiE59 (Usui et al. 1999) and missense hypomorphic fmiE86 (this study), and those of esn were a knockout allele, esnKO6 (this study), and a hypomorphic piggyBac insertion allele, esnf00447. Other strains employed were UAS-esnRNAi (transformant ID: 30037/construct ID: 7841, Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center), UAS-fmiRNAi (this study), Vangstbm6 (Wolff and Rubin 1998), VangA3 (Taylor et al. 1998), fzR52, dsh1 (Krasnow et al. 1995), RhoAE3.10 (Strutt et al. 1997), UAS-RhoAT19N (Bloomington Stock Center), trc1, trc2, fry1, fry6 (Emoto et al. 2004), and hpoMGH4 (Emoto et al. 2006).

Molecular cloning

The entire coding sequence of esn was amplified from a cDNA clone RE73081 (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center [DGRC]), and a one-base deletion of A2032 in RE73081 was fixed by PCR. pUAST-based plasmids were constructed and injected into flies by using standard methods to generate transgenic flies that expressed FmiTTV, FmiTTV:3eGFP (Harumoto et al. 2010), FmiTTVΔJM-A (an internal deletion of amino acid residues 3054–3153), mCherry:Esn, or mCherry:EsnΔLIM (a deletion of residues between 243 and 423). A GS spacer (GGGSGGGSGGGS) was used to fuse Fmi or Esn to three tandem copies of eGFP (Clontech, Takara Bio, Inc.) or to a single copy of mCherry (Shaner et al. 2004). S2 cells were used for the expression of 6Flag:FmiJM, 6Flag:FmiJM-A, 6Flag:FmiJM-B, and 6Myc:EsnLIM. To identify the fmiE86 mutation, we isolated genomic DNA from wild-type or fmiE86/Df(2R)E3363 trans-heterozygous adult escapers by conventional DNA isolation methods, amplified fmi coding regions, and determined their sequences. In situ hybridization was performed according to a standard protocol by using the esn cDNA as a template for making probes.

The six tandem repeats of a 20-base-pair (bp) sequence that includes a proneural binding site ([scE1]6) (Powell et al. 2004) was used to build a SOP-FLP transgene. The hsp70 minimal promoter and the entire coding sequence of flp from the UAS-FLP vector (DGRC) were inserted between [scE1]6 and SV40-polyA sequences.

Two-hybrid screening

The yeast strain AH109 was used for the two-hybrid analysis. Before our screening, we examined whether the Fmi C-tail or its subregions exhibited transactivation activity by itself or not, and found that JM was appropriate as bait. A Drosophila embryo cDNA library (#638839, Clontech) was used as prey. One of the positive clones in our screening encoded the LIM domain of Testin. This finding prompted us to examine whether JM of Fmi interacted with LIM domains of two other members of the Drosophila PET-LIM domain family, Prickle (Pk) and Espinas (Esn), and the results were positive. For matchmaking experiments, the yeast strain was transformed with the bait and each of the prey plasmids in Figure 2D according to the manufacturer's protocol (Matchmaker kit, Clontech). Transformed cells were plated on selective medium lacking Leu and Trp for 3 d before being streaked on medium lacking Leu, Trp, Ade, and His in order to test for potential interactions.

Immunoprecipitation, Western blotting, immunostaining, and in situ hybridization

S2 cells were transfected with expression plasmids and collected as described previously (Kimura et al. 2006), and then homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH7.4, containing 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1% Triton X-100, 1× phosphatase inhibitor cocktail EDTA-free [Nacalai Tesque], 1× Complete-mini EDTA-free [Roche]). Flag-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with an anti-Flag mouse monoclonal antibody (M2, Sigma). Precipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and then detected with anti-Flag rabbit antiserum (F7425, Sigma) or with anti-Myc rabbit antiserum (Myc-Tag antibody, Cell Signaling Technology). In Figure 2E and Supplemental Figure S2B, a sample of each lane was equivalent to 2.5% (input) or 16% (immunoprecipitation) of 4 mL of culture in a 6-cm dish. Larval CNS complexes were isolated from 100 dissected wandering third instar larvae and lysed in the lysis buffer above. Endogenous Fmi was immunoprecipitated with rat polyclonal anti-Fmi (Usui et al. 1999). In Figure 2F, a sample of each lane was equivalent to 2.25% (input) or 17.25% (immunoprecipitation) of the tissue lysate. Signals in Western blotting were acquired by using Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nacalai Tesque).

Transfected S2 cells were plated on ConA-coated dishes (Kimura et al. 2006) and viewed with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon C1). Immunostaining of whole-mount embryos was performed according to a standard protocol. To gain the stronger signals in anti-Esn immunostaining, we employed Can Get Signal Immunoreaction Enhancer solution (TOYOBO). Anti-Esn antibodies were generated by immunizing guinea pigs with maltose-binding protein fused to amino acids 1–133 (Esn-N) or amino acids 426–784 (Esn-C). Other antibodies employed were mouse monoclonal anti-Fmi (#74), mouse monoclonal 22C10 (Fujita et al. 1982), rabbit polyclonal anti-HRP (Jan and Jan 1982), and rat monoclonal anti-Dα-catenin DCAT1 (Oda et al. 1993).

For in situ hybridization, esn-specific riboprobe was prepared from a cDNA clone, RE73081 (DGRC). Hybridization and detection were performed as described (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989).

Knocking out the esn locus

esn was knocked out by the homologous recombination method basically as described previously (Rong and Golic 2000). Genomic fragments (4.9 kb and 3.9 kb) flanking the coding sequence were PCR-amplified and then cloned into an ends-out homologous recombination vector, pP{EndsOut2}, with a selectable marker, 70-white (Millard et al. 2007). w+ transformants were generated, and virgin female flies carrying the targeting construct on chromosome III were crossed to w/Y; +; 70-Flp 70-I-SceI males. Progeny were collected for 24-h periods and heat-shocked in a water bath for 1 h at 37°C each day for three consecutive days. Eclosing progeny were crossed to w; 70-Flp males, and female progeny that retained eye color were screened for the insertion of 70-white into the esn locus on chromosome II. Precise homologous recombination was confirmed by genomic PCR analysis.

Image acquisition of whole-mount animals, definition of branch crossing, and quantitative analysis

Live wandering larvae were mounted in 70%–100% glycerol and viewed with a Nikon C1 laser-scanning confocal microscope (or Bio-Rad MRC1024, only for Fig. 6G–I) with a 1.0-μm Z-step. For quantitative analysis in Figures 1 (G–H), 5 (F–G), and 6 (J–K), 512 × 512-pixel images of mostly dorsal dendritic branches were acquired by using a 40× objective lens without zooming, with cell bodies positioned at the middle lower sides (e.g., Figs. 1A–F, 6A–F).

Because dendrites extend on approximately two-dimensional planes underneath the epidermis, Z-series files of each neuron were projected, and then the sum of branch lengths of each projected image was measured by using Neurocyte (Kurabo). To quantitate the dendrite crossing phenotype, we excluded the neurons with obvious axonal defects. Crossing of branches was judged as follows: When we found a “cross” of two branches in the projected image, we examined the Z-stack series and determined which plane gave the highest signal intensity for each of the two branches. If the interval between the planes was within two steps, we designated such a “cross” as crossing; if not, we designated those “crosses” as overpasses. The crossing index of each cell was calculated for each projected image by dividing the number of its crossings by the sum of its own cumulative branch length. Results of statistical analyses are presented as means, and each error bar indicates the SD. The data of different genotypes were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc analysis, or by Student's t-test using KaleidaGraph (version 4.0; Synergy Software) and R (version 2.12.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

MARCM analysis

The MARCM analyses mediated by the heat-shock promoter (hs)-FLP were performed basically as described previously (Grueber et al. 2002). The animals were heat-shocked at the early–middle embryonic stages. SOP-FLP stock was employed to efficiently induce FRT-mediated recombination in the da neuron precursors.

Acknowledgments

The fly stocks and antibodies were provided by the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center at Kyoto Institute of Technology, the NIG stock center, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa. We thank FlyBase, Yash Hiromi, Kazuo Emoto, Wes Grueber, David Strutt, Paul N. Adler, Masakazu Yamazaki, Georg Halder, Lynn M. Powell, Takashi Nishimura, and Andy Jarman for other fly strains, materials, and related information. We also thank Tomonori Nakamura and Shinji Iwasaki for their contributions at the very initial stage of the project, F. Matsuzaki very much for his detailed technical advice on yeast two-hybrid screening, S. Yonehara for use of the DNA sequencer, and M. Futamata and J. Mizukoshi for their technical assistance. This work was supported by a CREST grant (to T. Uemura) from JST, a grant from the programs Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Mesoscopic neurocircuitry” (22115006 to T. Uemura), and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientist (B) (16770160 to T. Usui). D.M. is a recipient of a fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.16531611.

References

- Carmona-Fontaine C, Matthews HK, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Dunn GA, Parsons M, Stern CD, Mayor R 2008. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature 456: 957–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae J, Kim MJ, Goo JH, Collier S, Gubb D, Charlton J, Adler PN, Park WJ 1999. The Drosophila tissue polarity gene starry night encodes a member of the protocadherin family. Development 126: 5421–5429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PL, Clandinin TR 2008. The cadherin Flamingo mediates level-dependent interactions that guide photoreceptor target choice in Drosophila. Neuron 58: 26–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WS, Antic D, Matis M, Logan CY, Povelones M, Anderson GA, Nusse R, Axelrod JD 2008. Asymmetric homotypic interactions of the atypical cadherin flamingo mediate intercellular polarity signaling. Cell 133: 1093–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozatier M, Vincent A 2008. Control of multidendritic neuron differentiation in Drosophila: the role of Collier. Dev Biol 315: 232–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenport D, Fuchs E 2008. Planar polarization in embryonic epidermis orchestrates global asymmetric morphogenesis of hair follicles. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1257–1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenport D, Oristian D, Heller E, Fuchs E 2011. Mitotic internalization of planar cell polarity proteins preserves tissue polarity. Nat Cell Biol 13: 893–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto K, He Y, Ye B, Grueber WB, Adler PN, Jan LY, Jan YN 2004. Control of dendritic branching and tiling by the Tricornered-kinase/Furry signaling pathway in Drosophila sensory neurons. Cell 119: 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto K, Parrish JZ, Jan LY, Jan YN 2006. The tumour suppressor Hippo acts with the NDR kinases in dendritic tiling and maintenance. Nature 443: 210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Lu Q, Emoto K, Adler PN 2010. The Drosophila Fry protein interacts with Trc and is highly mobile in vivo. BMC Dev Biol 10: 40 doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala JC, Harris KM 1999. Dendrite structure. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PG, Koizumi A, Masland RH, Burgess RW 2008. Neurite arborization and mosaic spacing in the mouse retina require DSCAM. Nature 451: 470–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PG, Bruce F, Tian M, Wei W, Elstrott J, Feller MB, Erskine L, Singer JH, Burgess RW 2009. DSCAM and DSCAML1 function in self-avoidance in multiple cell types in the developing mouse retina. Neuron 64: 484–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita SC, Zipursky SL, Benzer S, Ferrus A, Shotwell SL 1982. Monoclonal antibodies against the Drosophila nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci 79: 7929–7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos ME, Bargmann CI 2004. Mechanosensory neurite termination and tiling depend on SAX-2 and the SAX-1 kinase. Neuron 44: 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao FB, Kohwi M, Brenman JE, Jan LY, Jan YN 2000. Control of dendritic field formation in Drosophila: the roles of flamingo and competition between homologous neurons. Neuron 28: 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueber WB, Sagasti A 2010. Self-avoidance and tiling: mechanisms of dendrite and axon spacing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a001750 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueber WB, Jan LY, Jan YN 2002. Tiling of the Drosophila epidermis by multidendritic sensory neurons. Development 129: 2867–2878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueber WB, Ye B, Moore AW, Jan LY, Jan YN 2003. Dendrites of distinct classes of Drosophila sensory neurons show different capacities for homotypic repulsion. Curr Biol 13: 618–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubb D, Green C, Huen D, Coulson D, Johnson G, Tree D, Collier S, Roote J 1999. The balance between isoforms of the prickle LIM domain protein is critical for planar polarity in Drosophila imaginal discs. Genes Dev 13: 2315–2327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeda-Suzuki S, Berger-Muller S, Tomasi T, Usui T, Horiuchi SY, Uemura T, Suzuki T 2011. Golden Goal collaborates with Flamingo in conferring synaptic-layer specificity in the visual system. Nat Neurosci 14: 314–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harumoto T, Ito M, Shimada Y, Kobayashi TJ, Ueda HR, Lu B, Uemura T 2010. Atypical cadherins Dachsous and Fat control dynamics of noncentrosomal microtubules in planar cell polarity. Dev Cell 19: 389–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Sugimura K, Uemura T 2007. Selective expression of Knot/Collier, a transcriptional regulator of the EBF/Olf-1 family, endows the Drosophila sensory system with neuronal class-specific elaborated dendritic patterns. Genes Cells 12: 1011–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Bortnick R, Tsubouchi A, Baumer P, Kondo M, Uemura T, Schmucker D 2007. Homophilic Dscam interactions control complex dendrite morphogenesis. Neuron 54: 417–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan LY, Jan YN 1982. Antibodies to horseradish peroxidase as specific neuronal markers in Drosophila and in grasshopper embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci 79: 2700–2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan YN, Jan LY 2010. Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 316–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinushi-Nakao S, Arvind R, Amikura R, Kinameri E, Liu AW, Moore AW 2007. Knot/Collier and cut control different aspects of dendrite cytoskeleton and synergize to define final arbor shape. Neuron 56: 963–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadrmas JL, Beckerle MC 2004. The LIM domain: from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 920–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Usui T, Tsubouchi A, Uemura T 2006. Potential dual molecular interaction of the Drosophila 7-pass transmembrane cadherin Flamingo in dendritic morphogenesis. J Cell Sci 119: 1118–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnow RE, Wong LL, Adler PN 1995. Dishevelled is a component of the frizzled signaling pathway in Drosophila. Development 121: 4095–4102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Clandinin TR, Lee CH, Chen PL, Meinertzhagen IA, Zipursky SL 2003. The protocadherin Flamingo is required for axon target selection in the Drosophila visual system. Nat Neurosci 6: 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London M, Hausser M 2005. Dendritic computation. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 503–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H, Ou Y, Rao Y, van Meyel DJ 2009. Dendrite branching and self-avoidance are controlled by Turtle, a conserved IgSF protein in Drosophila. Development 136: 3475–3484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews BJ, Kim ME, Flanagan JJ, Hattori D, Clemens JC, Zipursky SL, Grueber WB 2007. Dendrite self-avoidance is controlled by Dscam. Cell 129: 593–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard SS, Flanagan JJ, Pappu KS, Wu W, Zipursky SL 2007. Dscam2 mediates axonal tiling in the Drosophila visual system. Nature 447: 720–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narimatsu M, Bose R, Pye M, Zhang L, Miller B, Ching P, Sakuma R, Luga V, Roncari L, Attisano L, et al. 2009. Regulation of planar cell polarity by Smurf ubiquitin ligases. Cell 137: 295–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda H, Uemura T, Shiomi K, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M 1993. Identification of a Drosophila homologue of α-catenin and its association with the armadillo protein. J Cell Biol 121: 1133–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Zur Lage PI, Prentice DR, Senthinathan B, Jarman AP 2004. The proneural proteins Atonal and Scute regulate neural target genes through different E-box binding sites. Mol Cell Biol 24: 9517–9526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter JE, Nardine TM, Penton A, Billuart P, Scott EK, Usui T, Uemura T, Luo L 2003. A mosaic genetic screen for genes necessary for Drosophila mushroom body neuronal morphogenesis. Development 130: 1203–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong YS, Golic KG 2000. Gene targeting by homologous recombination in Drosophila. Science 288: 2013–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senti KA, Usui T, Boucke K, Greber U, Uemura T, Dickson BJ 2003. Flamingo regulates R8 axon–axon and axon–target interactions in the Drosophila visual system. Curr Biol 13: 828–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol 22: 1567–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima Y, Kengaku M, Hirano T, Takeichi M, Uemura T 2004. Regulation of dendritic maintenance and growth by a mammalian 7-pass transmembrane cadherin. Dev Cell 7: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima Y, Kawaguchi SY, Kosaka K, Nakayama M, Hoshino M, Nabeshima Y, Hirano T, Uemura T 2007. Opposing roles in neurite growth control by two seven-pass transmembrane cadherins. Nat Neurosci 10: 963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono K, Sugimura K, Kengaku M, Uemura T, Mochizuki A 2010. Computational modeling of dendritic tiling by diffusible extracellular suppressor. Genes Cells 15: 137–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Mlodzik M 2008. Planar cell polarity signaling: from fly development to human disease. Annu Rev Genet 42: 517–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soba P, Zhu S, Emoto K, Younger S, Yang SJ, Yu HH, Lee T, Jan LY, Jan YN 2007. Drosophila sensory neurons require Dscam for dendritic self-avoidance and proper dendritic field organization. Neuron 54: 403–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimel A, Wong L, Najarro EH, Ackley BD, Garriga G, Hutter H 2010. The Flamingo ortholog FMI-1 controls pioneer-dependent navigation of follower axons in C. elegans. Development 137: 3663–3673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanyants A, Chklovskii DB 2005. Neurogeometry and potential synaptic connectivity. Trends Neurosci 28: 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Strutt D 2008. Differential stability of flamingo protein complexes underlies the establishment of planar polarity. Curr Biol 18: 1555–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt DI, Weber U, Mlodzik M 1997. The role of RhoA in tissue polarity and Frizzled signalling. Nature 387: 292–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt H, Warrington SJ, Strutt D 2011. Dynamics of core planar polarity protein turnover and stable assembly into discrete membrane subdomains. Dev Cell 20: 511–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura K, Yamamoto M, Niwa R, Satoh D, Goto S, Taniguchi M, Hayashi S, Uemura T 2003. Distinct developmental modes and lesion-induced reactions of dendrites of two classes of Drosophila sensory neurons. J Neurosci 23: 3752–3760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney NT, Li W, Gao FB 2002. Genetic manipulation of single neurons in vivo reveals specific roles of flamingo in neuronal morphogenesis. Dev Biol 247: 76–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeichi M 2007. The cadherin superfamily in neuronal connections and interactions. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 11–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C 1989. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma 98: 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Abramova N, Charlton J, Adler PN 1998. Van Gogh: a new Drosophila tissue polarity gene. Genetics 150: 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault ST, Singer MA, Miyazaki WY, Milash B, Dompe NA, Singh CM, Buchholz R, Demsky M, Fawcett R, Francis-Lang HL, et al. 2004. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat Genet 36: 283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissir F, Bar I, Jossin Y, De Backer O, Goffinet AM 2005. Protocadherin Celsr3 is crucial in axonal tract development. Nat Neurosci 8: 451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tree DR, Shulman JM, Rousset R, Scott MP, Gubb D, Axelrod JD 2002. Prickle mediates feedback amplification to generate asymmetric planar cell polarity signaling. Cell 109: 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Shima Y, Shimada Y, Hirano S, Burgess RW, Schwarz TL, Takeichi M, Uemura T 1999. Flamingo, a seven-pass transmembrane cadherin, regulates planar cell polarity under the control of Frizzled. Cell 98: 585–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladar EK, Antic D, Axelrod JD 2009. Planar cell polarity signaling: the developing cell's compass. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a002964 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Okamoto H 2009. Roles of planar cell polarity pathway genes for neural migration and differentiation. Dev Growth Differ 51: 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Tanaka H, Nakayama S, Iwasaki M, Okamoto H 2006. Frizzled3a and Celsr2 function in the neuroepithelium to regulate migration of facial motor neurons in the developing zebrafish hindbrain. Development 133: 4749–4759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassle H, Peichl L, Boycott BB 1981. Dendritic territories of cat retinal ganglion cells. Nature 292: 344–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T, Rubin GM 1998. Strabismus, a novel gene that regulates tissue polarity and cell fate decisions in Drosophila. Development 125: 1149–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Zhu J, Wang Y, Zhou J, Ren K, Ding X, Zhang J 2009. LIM domain protein TES changes its conformational states in different cellular compartments. Mol Cell Biochem 320: 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Bar I, Achouri Y, Campbell K, De Backer O, Hebert JM, Jones K, Kessaris N, de Rouvroit CL, O'Leary D, et al. 2008. Early forebrain wiring: genetic dissection using conditional Celsr3 mutant mice. Science 320: 946–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn K 2004. Dendritic tiling; new insights from genetics. Neuron 44: 211–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky SL, Sanes JR 2010. Chemoaffinity revisited: dscams, protocadherins, and neural circuit assembly. Cell 143: 343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]