Abstract

A total of $275 million has been launched to The Cancer Genome Atlas Project for genomic mapping of more than 20 types of cancers. The major challenge is to develop high throughput and cost-effective techniques for human genome sequencing. We developed a targeted exome sequencing technology to routinely determine human exome sequence. As a proof-of-concept, we chose a unique patient, who underwent three high mortalities cancers, i.e., breast, gallbladder and lung cancers, to reveal the genetic cause of high-cancer-susceptibility. Total 24,545 SNPs were detected. 10,868 (44.27%) SNPs were within coding regions, and 1,077 (4.38%) located in the UTRs. 3367 genes were hit by 4480 non-sysnonymous mutations in CDS with truncation of 30 proteins; and 10 mutations occurred at the splice sites that would generate different protein isoforms. Substitutions or premature terminations occurred in 132 proteins encoded by cancer-associated genes. CARD8 was completely loss; ANAPC1 was pre-translationally terminated from the transcripts of one allele. On the Ras-MAPK pathway, 18 genes were homozygously mutated. 15 growth factors/cytokines and their receptors, 9 transcription factors, 6 proteins on WNT signaling pathway, and 16 cell surface and extracellular proteins may be dysfunctioned. Exome sequencing made it possible for individualized cancer therapy.

Keywords: whole-exome sequencing, cancer, genetic variations, high-cancer-susceptibility

Introduction

It has always been bothering physicians to choose correct drugs as the anticancer effects are completely different among patients [1-3]. This is caused by not only the multiple genetic mutations in human cancers but also a wide variety of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of individuals [4]. Mutations in exons, such as mutations on H-RAS, p53 and APC genes, are often found to cause human cancers. Up to date, 73 genes with germline mutations and 412 genes with germline or somatic alterations, including amplification, deletion, rearrangement and point mutations, have been shown to be involved in human cancers in the Cancer Gene Census of Cancer Genome Project database (CGC/CGP, www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/Census). In the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics Oncology and Haematology (AGCOH) database (atlasgenetics-oncology.org/Indexbychrom/), there are 766 annotated genes that are genetically associated with cancers and other 3,000 other genes are functionally involved in the process of cancer development. Although a great advance has been achieved for early diagnosis of human cancers and anticancer drug development, the mobility of cancer cases is increasing while the average mortality almost remains consistent in the last decades [5, 6]. The random use of anticancer drugs largely neutralized the attempts of anticancer treatment; and cancer is still the second killer of human diseases. Therefore, it is urgently needed to develop genome-based individualized cancer therapy and care.

It is well known that the whole exome constitute only about 1% of the human genome but harbor the major of mutations contribute to cancer development. Therefore, combined with bioinformatics analysis, targeted exome sequencing technology would be a good and practical strategy to largely reduce the cost and labor load. It would also have a great potential to expand our knowledge of rare mutations in cancer development and to accelerate the functional studies of cancer-associated genes. Using high susceptibility of cancers as proof-of-concept, we observed that 132 genes, which have been shown to be important for cancer development, dysfunctioned or functionally alternated. Of them, only 11 genes were germline-mutated according to CGC/CGP database; while the mutations of other 121 genes were newly identified in germline in cancer patient.

Material and methods

Patient

A very unique cancer patient, a Chinese women (YH2), was recruited in this study. She underwent breast cancer, gallbladder adenocacinoma and lung cancer at 41, 63 and 66, respectively. She died of recurrence of gallbladder adenocacinoma in liver at 68. The tumors were removed by surgery at the diagnosis and tumor types were determined by histochemisty assays after surgery. There was no family history of cancers. Informed comment was obtained from the patient for this study, and the study was approved by the ethic committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Exome sequencing

The strategy for exome sequencing was similar as described by Ng et al [7]. In brief, shotgun libraries were generated from 10 ug of blood leukocytes purified genomic DNA (gDNA) using the standard Illumina protocols [8]. The fragments of size 150-200 bp were isolated after electrophoresis on 6% PAGE and hybridized with NimbleGen 2.1M-probe sequence capture array (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/seqcap), in which oligos were fixed to cover the human exomes (RefSeq, NCBI 36.3, 33.92 Mb). The captured exomes were applied for direct single-end sequencing on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. The average read for each probe is 75 bases. Sequences were then aligned to the reference (RefSeq, hg18, 19 and YH1) [9] using SOAPaligner, and the mapped bases, depth, coverage and the base distribution were analyzed.

Substitution detection

SNPs were called by SOAPsnp based on the alignments with HapMap database (www.hapmap.org). For each site within the exome targeted region, only copy number <1.5 of the surrounding area was allowed and the depth should range from 10X to 200X. Finally, a Q20 threshold was used to filter unreliable SNPs. After excluding known substitutions from the potential mutations available, the SNPs were annotated and the genes involved in cancer development were revealed by comparison of our data with CGC/CGP and the AGCOH database.

Insertion and deletion detection

For the single reads we produced, the short in-dels <4 bp were also identified by S0APaligner2 in a gap tolerable mode. Local alignments were performed with our custom perl scripts.

Results

Exome sequences

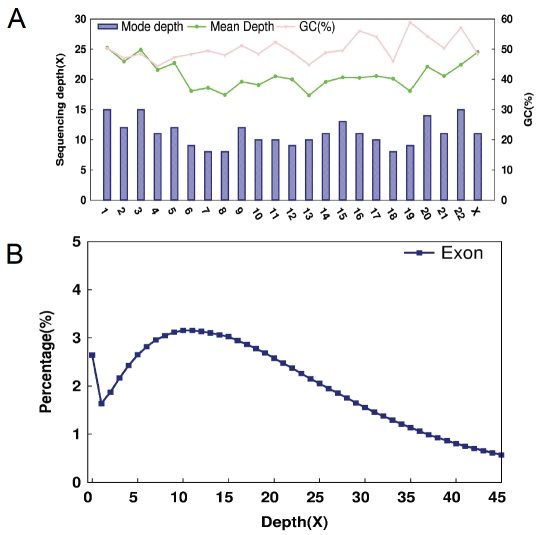

Our sequencing strategy was similar to the one published by Ng et al recently but with a larger coverage (33.92 instead of 26.6 megabases) [7]. The average sequencing depth was 21.1 (Figure 1). The total reads were about 1.97 Gagabases (GBs) which covered 97.36% of the reference. With SOAPaligner software, 87.92% of bases were aligned to the reference (build 131,10/03/26, hg18 and hg19) and YH genome sequence [9]. The mismatch rate was 0.65%, indicating the data was in high sequencing quality. We detected total 24,545 SNPs. Among them, 10,874 (44.3%) SNPs located in the coding regions and 142 (0.6%) SNPs located in the UTRs. There were 23,604 SNPs were shared among YH1 and dbSNPs, while 941 SNPs were newly identified in the patient after comparative analysis of SNPs in the captured exome. Among them, 8091 SNPs (42.81%) were homozygous. 3058 genes were hit by 4480 non-synonymous mutations in the coding sequences (CDS). 10 mutations displayed at spice sites, and 8 small in/dels were identified.

Figure 1.

Targeted capture exome sequencing. A. Chromosome depth and GC distribution in targeted capture exome regions. X axis stands for each chromosome, Y1 axis presents the sequencing depth and YH2 axis is the GC proportion in exon capture region of each chromosome. B. Nu-cleotide distribution under different depth in exon capture region. Y axis stands for the proportion of bases under each depth in exon capture region.

Nonsense mutations

We detected 33 nonsense mutations that caused truncation of 30 proteins (Table 1). We found only 3 proteins (PTPN11, MAGEE2 and IL17RB) have been recorded to have genetic associations with cancer [10-12]; while 11 other cancer-associated proteins, for the first time, were observed to be mutated in the germline. Particularly, MAGEE2, which has been shown genetic association in melanoma and hepato-cellular carcinoma, was truncated at N-terminal by homozygous mutations. CARD8, a key factor for the recruitment of caspase in apoptosis pathway[13], was almost completely loss in the patient. ANAPC1, a key components of ana-phase promoting complex that play crucial roles in cell mitosis and protection of the integration of chromosomes from separation [14-17], truncated >70% by a heterozygous mutation at Gln465. Some important proteins on the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway, including G protein coupled receptor 1 (GRP1), tyrosine kinase (MAP2K3), and protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN11), also prematurely terminated.

Table 1.

Nonsense mutations (ST, stop; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome)

| Name | type | mutation | Position (stop) | full length (aa) | function | Genetic association with disease(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional associated with cancers | ||||||

| ANAPC1 | HET | CAG>TAG | Q465 | 1926 | anaphase promoting complex | |

| GPR1 | HET | CGA>TGA | R236 | 355 | signal transduction | |

| ASCC3 | HET | CAG>TAG | Q87 | 111 | signal transduction | |

| MAP2K3 | HET | CAG>TAG | Q73 | 318 | tyrosine kinase, signal transduction | |

| PTPN11 | HET | TAT>TAG | Y197 | 593 | protein tyrosine phosphatases | JMML, AML, MDS |

| MAGEE2 | HOM | GAG>TAG | E120 | 523 | signal transduction | melanoma, HCC |

| CARD8 | HOM | TGT>TGA | C10 | 432 | caspase recruitment | rheumatoid arthritis |

| ABCA10 | HET | CGA>TGA | R1322 | 1544 | drug transport | |

| CYP2C18 | HET | TAT>TAA | Y68 | 490 | drug metabolism | |

| IL17RB | HET | CAG>TAG | Q484 | 502 | cytokine receptor | intestinal inflammation |

| UBE2NL | HET | TTA>TGA | L89 | 153 | ubiquitin ligation | |

| FTHL17 | HET | GAG>TAG | E148 | 183 | ferritin heavy polypeptide-like protein | |

| TP53RK | HET | CGA>TGA | R152 | 254 | TP53-regulating kinase | |

| Others | ||||||

| SPATA21 | HET | CGA>TGA | R467 | 470 | spermatogenesis | |

| PZP | HET | CAA>TAA | Q598 | 1483 | proteinase inhibitor | |

| UNC5CL | HET | CAG>TAG | Q12 | 519 | NF-kB inhibitor | |

| TCTE1 | HET | CAG>TAG | Q460 | 502 | t-complex-associated-testis-expressed 1 | |

| ASCC3 | HET | CAG>TAG | Q87 | 2203 | RNA helicase | |

| ZNF75D | HET | CGA>TGA | R331 | 511 | transcriptional factor | |

| DKFZp547 | HOM | TGG>TGA | W141 | 150 | unknown | |

| LOC149643 | HET | CGA>TGA | R37 | 98 | unknown | |

| MS4A12 | HET | CAA>TAA | Q71 | 267 | membrane protein | |

| OR2T5 | HET | CGA>TGA | R24 | 315 | olfactory receptor | |

| PZP | HET | CAA>TAA | Q598 | 1483 | pregnancy-zone protein | |

| SLC6A18 | HET | TAC>TAG | Y319 | 628 | unknown | |

| SPATA21 | HET | CGA>TGA | R467 | 470 | spermatogenesis | |

| ZNF75 | HET | CGA>TGA | R331 | 510 | zinc finger protein | |

| ZNF80 | HET | TAT>TAG | Y245 | 273 | zinc finger protein | |

| PTCHD3 | HET | TAA>CAA | ST768Q | 767 | spermatogenesis | |

Missense mutations

Missensense mutations hit over 3,000 proteins. After aligned with the CGC/CGP and AGCOH databases, we observed important substitutions (most likely causing function alterations) occurred in 132 proteins, which strongly associated with cancer development (Table 3). Among them, 45 have been recorded as somatic mutations and only 11 recorded as germline mutations in cancer patients in the CGC/CGP database. Totally 121 cancer-associated genes were newly found to display mutations in germline; some mutations would cause significant function alterations.

Table 3.

Mutations in the genes strongly associated with human cancers

| Gene | type | FL (aa)1 | mutation | Somatic | germline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACSL3 | Het | 719 | L641H | prostic cancer | |

| ADAM12 | Hom | 1593 | G48R | ||

| ADAM8 | Hom | 823 | W35R, F657L | ||

| ADAMST5 | Het | 929 | R614H,L692P | ||

| ADAMTS4 | Het | 837 | Q626R | ||

| AFF3 | Hom | 1226 | S538N | ||

| AKAP12 | Het | 1683 | K118Q,K1218I | multiple cancers, anti-angiogenesis | |

| AKR1C4 | Hom | 324 | S145C*, Q250R, L311V* | ||

| ALOX12 | Hom | 662 | N322S | ||

| ANAPC1 | Het | 1926 | Q465ST(GAC->TAC) | ||

| APC | Hom | 2843 | V1288D | colorectal, pancreatic, desmoid, hepatoblastoma, glioma, other CNS cancers | the same cancers as somatic mutations |

| ASNS | Het | 561 | V210E | ||

| ASXL1 | Hom | 1541 | L815P | MDS, CMML | |

| ATF6 | Het | 670 | A145P, P157S | leukemia, lymphoma, medulloblastoma, glioma | |

| ATM | Hom | 3056 | N1983S | T-PLL | |

| BCAS1 | Hom | 584 | Q24K, V163A* | ||

| BCL2A1 | Het | 174 | C19Y, N39K, G82D | ||

| BCL2L2 | Hom | 193 | Q133R | ||

| BCL9 | Het | 1426 | A218V | B-ALL, Hodgkin lymphoma | colon/breast/ovary cancer, AML, leukemia, rhabdomyosarcama |

| BMPR1A | Het | 531 | P2T | breast cancer | AML, leukemia, breast cancer |

| BRIP1 | Hom | 1249 | S919P | ||

| BUB1B | Hom | 1049 | R349Q | colorectal cancer, breast cancer | gastrointestinal neoplasia, rhabdomyosarcoma |

| CABC1 | Het | 647 | H85Q | ||

| CARD8 | Hom | 432 | C10st (TGT->TGA) | ||

| CARS | Het | 879 | A774T | ALCL | |

| CBLB | Het | 981 | N466D | AML | |

| CCND3 | Het | 292 | S259A | MM | |

| CD97 | Hom | 785 | R318Q | ||

| CDH11 | Hom | 795 | T255M*, M275I*,S373A | aneurismal bone cycs | |

| CDX2 | Hom | 313 | P293S | AML | |

| CENPF | Hom | 3113 | R2729Q, R2943G, N3106K | ||

| COL1A1 | Hom | 1465 | T1075A | ||

| COL1A2 | Hom | 1365 | P549A | dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | |

| DDX43 | Hom | 647 | K625E | ||

| DKK2 | Hom | 259 | R146Q | ||

| DKK3 | Hom | 349 | R335G | gastric/lung/breast/prostate/ovary cancer, glioma | |

| EML4 | Hom | 980 | K283E | NSCLC | |

| ENPP2 | Hom | 865 | S493E | ||

| EPHA1 | Hom | 976 | V160A | ||

| ERCC2 | Het | 759 | K751N | skin basal cell, melanoma, SKC, | |

| ERCC5 | Hom | 1186 | G1053R, G1080R, D1104H | skin basal cell, SKC, melanoma | |

| FANCA | Hom | 1453 T266A, A412V*, G501S, P643A*, G809D, T1328A* | AML, leukemia | ||

| FGFR2 | Het | 820 | M186T | gastric, endometrial cancer, NSCLC | |

| FGFR4 | Hom | 802 | V10I | ||

| FLT3 | Het | 992 | T227M, D358V | AML, ALL | |

| FNIP1 | Hom | 1165 | G76C, Q648R | ||

| FTHL17 | Het | 183 | E148st (GAG->TAG) | ||

| FXYD5 | Hom | 178 | S35A, R176H* | ||

| GATA2 | Hom | 479 | A146T | AML | |

| GGH | Het | 317 | C6R | ||

| GOLGA5 | Hom | 730 | A67G*,P350L | papillary thyroid | |

| GPR1 | Het | 355 | R236st (CGA->TGA) | ||

| GPR103 | Hom | 431 | L344S | ||

| GPR112 | Hom | 3080 | I276M*, P368H*,T1213N, S1540P, F1791L | ||

| GPR116 | Hom | 1345 | T604M | ||

| GPR142 | Hom | 462 | H132N | ||

| GPRC6A | Hom | 925 | P91S | ||

| GRP115 | Hom | 694 | K541N | ||

| GRP56 | Hom | 692 | S281R | ||

| HTATIP2 | Hom | 276 | S231R | ||

| IGF2R | Hom | 2491 | R1619G, N2020S | ||

| IL23R | Hom | 628 | Q3H, L310P | ||

| JAG2 | Het | 1237 | E501K | ||

| KLK10 | Hom | 275 | S50A, L149P* | ||

| KLK4 | Hom | 250 | S22A*, H179Q | ||

| KLK5 | Hom | 292 | N153D | ||

| LCP1 | Hom | 626 | K553E | NHL | |

| LIFR | Hom | 1097 | D578N | salivary adenoma | |

| LOX | Hom | 417 | R158Q | ||

| LOXL2 | Hom | 773 | M570L | ||

| LOXL4 | Hom | 755 | R154Q | ||

| MAP2K3 | Het | 317 | Q73st (CAG->TAG) | ||

| MAP3K7IP1 | Het | 503 | C235W | ||

| MEN1 | Hom | 614 | T546A | parathyroid tumors | parathyroid/pituitary/pancreatic/characinoid adenoma |

| MGC34647 | Het | 266 | Y213st (TAC->TAG) | ||

| MMP10 | Het | 475 | D81Y | ||

| MMP11 | Hom | 486 | A38V | ||

| MMP17 | Hom | 602 | A182T | ||

| MMP20 | Hom | 482 | K18T*, V275A,T281N | ||

| MMP26 | Hom | 260 | K43E | ||

| MMP27 | Hom | 512 | M30V | ||

| MMP8 | Hom | 467 | K87E | ||

| MMP9 | Het | 706 | Q279R | ||

| MST1 | Het | 724 | R108Q, R122Q | breast cancer | |

| MST1R | Hom | 1399 | Q523R/E, S1195G, R1135G/E | ||

| MTHFR | Het | 655 | A222V | ||

| MYEOV | Het | 312 | V159A, R198Q, G271R | ||

| MYH11 | Het | 1937 | N1899S | AML | |

| MYST3 | Het | 2003 | L134S | ||

| NBN | Het | 753 | E185Q | ||

| NIN | Hom | 2045 | Q1125P, G1320E | MPD | |

| NOTCH2NL | Het | 235 | S67P, P133L, T158I, S181R, P188H | marginal zone lymphoma, DLBCL | |

| NQO1 | Het | 239 | Q139W | ||

| NSD1 | Het | 2695 | S726P | AML | |

| NUP214 | Het | 2090 | P754S | AML | |

| NUT | Hom | 1131 | P22L | lethal midline carcinoma | |

| OPTN | Hom | 576 | M98K*, K322E | ||

| P2RX7 | Hom | 594 | Y155H*, R270H*, E496A*, N568I | ||

| PBX1 | Het | 429 | G21S | Pre B-ALL | |

| PDE4DIP | Hom | 2345 | R25L*, A167T*, R681H*, C708R, R1504Q* | MPD | |

| PDGFRA | Het | S361R, T474M,S478P | GIST, idiopathic hyperosinophilic syndrome | ||

| PLAG1 | Het | 500 | S443R | salivary adenoma, pleomorphic adenoma | |

| PML | Het | 828 | S722G | APL | |

| PMS2 | Hom | 861 | P470S*, T485K*, K541E | colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, medulloblastoma, glioma | |

| POU6F2 | Hom | 691 | P191L | ||

| PPARGC1A | Hom | 797 | G482S | ||

| PTPN11 | Het | 592 | S189A, Y197st (TAT->TAG) | JMML, AML, MDS | |

| PTPN21 | Het | 1173 | L385F, V936A | ||

| PVRL4 | Het | 509 | F53L | ||

| REL | Het | 618 | N424S | many cancers and other disease | |

| RHOD | Hom | 210 | C134R | ||

| RHOT2 | Het | 617 | A88T, R245Q | ||

| ROS1 | Het | 2347 | T145P | ||

| SDC1 | Hom | 310 | L136Q | ||

| SELE | Het | 371 | S303R | ||

| SERPINB5 | Het | 374 | S176P, I319V | ||

| SFRP4 | Het | 345 | P320T, R340K | ||

| STEAP2 | Hom | 489 | F17C*, R456Q*, M475I | ||

| TCF3 | Het | 653 | P479L | pre B-ALL | |

| TEK | Hom | 1123 | I148T*, Q346P | ||

| TFEB | Het | 475 | V130M | renal (childhood) epithelioid | |

| TFRC | Het | 760 | G142S | NHL | |

| THBS4 | Hom | 1538 | I192T, I598T, S1055G | ||

| TMPRSS2 | Het | 491 | V160M | prostate | |

| TNC | Hom | 2200 | V295M*, Q539R, V605I, E2008Q* | glioma, lung/colon/breast cancer | |

| TNFRSF10A | Hom | 467 | H141R, R209T, R441K | ||

| TNFRSF17 | Hom | 183 | N81S | intestinal T-cell lymphoma | |

| TRAF3 | Hom | 568 | M129T | ||

| TSC1 | Het | 365 | M322T | ||

| USP6 | Het | 234 | Y162H, W475R, Y484H | aneurysmal bone cysts | |

| WISP3 | Het | 331 | Q34H, E100K, E141K | colon cancer | hamartoma, renal cell carcinoma |

ALCL, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphocytic leukaemia; CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CNS, central nervous system; DLBL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DLCL, diffuse large-cell lymphoma; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumour; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MLCLS, mediastinal large cell lymphoma with sclerosis; MM, multiple myeloma; MPD, Myeloproliferative disorder; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NSCLC, non small cell lung cancer; pre-B All, pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; SKC, skin squamous cell; T-PLL, T cell prolymphocytic leukaemia.

listed as heterozyous mutation.

Homozygous mutations displayed in 58 genes that may contribute to high susceptibility of cancers in this patient. Homozygous missense mutations occurred in 18 genes on RAS-MARK pathway, including G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs), tyrosine kinases and phosphatases (Table 2). On this pathway, heterozygous mutations hit 9 other genes, including AKAP12, CBLB, MAP2K3, MAP3K7IP1, PTPN11, PTPN21, TCL1B and USP6 (Table 3). Although the proteins encoded by these genes play critical roles in cells response to extracellular signalings [18, 19]; however, only EML4 and NIN were recorded somatic mutations in tumors in the CGC/CGP database. The second largest group (10 genes), which were hit by homozygous mutations, were growth factors/cytokines and their receptors. Although only mutation of TNFRSF17 was shown in the intestinal T-cell lymphoma in the database, the products of these genes are important to control cell growth and immune responses to infection and other human diseases including carcinogenesis. On the Wnt signaling pathway, besides APC, homozygous mutations of CD97, DKK2 and DKK3 most likely cause significant alteration of protein functions. The genetic alterations in tumors have not yet recorded. Apart from DDX43, the other homozy-gously mutated genes (ATM, BUB1B, ERCC5 and FANCA) for cell cycle control and DNA/RNA process were shown genetic association with cacinogenesis (Table 2). Besides function association, the germline mutations of transcription factors (AFF3 and POU6F2) have not yet recorded. All 3 apoptotic/anti-apoptotic genes (CARD8, BCL2L2 and OPTN) were newly observed genetic alterations in cancer patients. This would enhance the somatic cells escaping from apoptosis during carcinogenesis.

Table 2.

Homozygous mutation(s) in genes strongly (either genetically or functionally) associated with carcinogenesis (*, heterozygous mutation)

| Name | Full length (FL, aa) | mutations | Name | FL (aa) | mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAS-MAPK signaling pathway | Wnt signaling pathway | ||||

| EML4 | 981 | K283E | APC | 2843 | V1822D |

| ENPP2 | 865 | S493P | CD97 | 786 | R318Q |

| EPHA1 | 976 | M900V | DKK2 | 259 | R146Q |

| FNIP1 | 1166 | G76C, Q648R | DKK3 | 350 | R335G |

| GPR103 | 431 | L344S | Growth factors/cytokines and their receptors/signal transducers | ||

| GPR112 | 3080 | T1213N.S1540P, F1791L, I276M*, P368H* | FGFR4 | 802 | V10I, P136L |

| GPR116 | 1346 | T604M | IGF2R | 2491 | R1619G, N2020S * |

| GPR142 | 462 | H132N | IL23R | 629 | Q3H, L310P |

| GPRC6A | 926 | P91S | MST1R | 1400 | Q523R(E), S1195G, R1335G(E) |

| GRP115 | 695 | K541N | PPARGC1A | 798 | G482S |

| GRP56 | 693 | S281R | TNC | 2201 | V295M*, Q539R, V605I, E2008Q* |

| KLK4 | 251 | S22A*, H197Q | TNFRSF10A | 468 | H141R, R209T, R441K |

| KLK5 | 293 | N153D | TNFRSF17 | 184 | N81S |

| KLK10 | 276 | S50A, L149P* | TRAF3 | 568 | M129T |

| KLK11 | 250 | G17E | PLEK2 | 354 | S217C |

| NIN | 2046 | Q1125P, G1320E | Cell cycle control | ||

| RHOD | 210 | C134R | ATM | 3056 | N1983S |

| TEK | 1124 | I148T*, Q346P | BUB1B | 1050 | R349Q |

| Apoptosis/anti-apoptosis | Others | ||||

| CARD8 | 432 | C10ST | ASXL1 | 1541 | L815P |

| BCL2L2 | 194 | Q133R | CDH11 | 796 | T255M*, M275I*,S373A |

| OPTN | 577 | M98K*, K322E | BRIP1 | 1249 | S919P |

| DNA repair/RNA synthesis | COL1A1 | 1464 | T1075A | ||

| ERCC5 | 1186 | G1053R, G1080R, D1104H | GOLGA5 | 731 | A67G*,P350L |

| FANCA | 1454 | T266A,A412V*,G501S,P643A*,G809D, T1328A* | LCP1 | 627 | K533E |

| DDX43 | 648 | K625E, Q629R | LIFR | 1098 | D578N |

| ATM | 3056 | N1983S | MAGEE2 | 523 | E120ST(GAG>TAG) |

| BUB1B | 1049 | R349Q | MEN1 | 615 | T546A |

| Transcription factors | NUT | 1132 | P22L | ||

| AFF3 | 1226 | S538N | PDE4DIP | 2346 | R25L*, A167T*, R681H*, C708R, R1504Q* |

| CDX2 | 313 | P293S | PMS2 | 862 | P470S*, T485K*, K541E |

| GATA2 | 480 | A146T | P0U6F2 | 691 | P191L |

Discussion

The Cancer Genome Atlas project is currently the central task of genome-related research. It remains largely unknown how germline mutations in global contribute to cancer-susceptibility, although it is well known some germline mutations in a special gene would cause human cancers (e.g., mutaions in pRB gene leads to retinoblastoma in children). The major challenge is to develop a high throughput and cost-effective techniques for genome sequencing. Supported with extensive bioinformatic assays, a US group [7] and us have independently developed cost-effective targeted capture exome sequencing technology to routinely reveal the genetic variations of individuals. However, to our knowledge, the whole exome sequencing on high-cancer-susceptible patient has not yet been studied. In this study, we independently developed a similar technology for the whole exome sequencing. As a pilot study, we showed that homozygous mutations of CARD8 may contribute to the high-cancer-susceptibility in a patient, who underwent three high mortality cancers (breast cancer, gallbladder cancer and lung cancer) in the last three decades.

CARD8 was reported to inhibit apoptosis and caspase activation induced by Apaf-1/caspase-9-dependent stimili [20]; however, it was also showed to induce apoptosis in certain cells [13]. It is unclear how the loss of CARD8 contributes the high-cancer-susceptibility in this patient. The mutations in other genes, such as genes on RAS-MARK signaling pathway, may also play important roles in high-cancer-susceptibility. However, as some mutations may neutralize or antagonize the other mutations, the exact roles of these mutations are very complicated in the patient. For example, the truncation of MAGEE2 and PTPN11 may neutralize the mutations of tyrosine kinases and GPRs. The roles of these mutations in cancer-susceptibility would be further investigated by identification of more high-cancer-susceptibility patients or direct sequencing the tumor samples and paired germline genomes.

In summary, we developed targeted exome capture sequencing technology to characterize the whole-exome of human genome and applied to a high-cancer-susceptible patient. We showed that the truncations of CARD8, MAGEE2, ANAPC1, GPR1, ASCC3, MAP2K3 and PTPN11 be an important reasons for high-cancer-susceptiblity. The non-synonymous mutations in 132 cancer-associated genes, in which most of them have not been reported as germline variations in tumors, may positively or negatively contribute to cancer development. This exome sequencing technology makes it possible for routine dissection of important genes for carcinogenesis and individualized medicine, as the total cost is just less than US$10,000 per sample. The targeted exome capture sequencing would be a new era of individualized cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in partial by Shenzhen -Hong Kong Collaborative Research Grant of Shenzhen Science and Technology Bureau (08DF-23, to ML He and Y He) and Research Grant Council, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administration Region (CUHK4428/ 06M,toMLHe).

Declaration

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morrow PK, Hortobagyi GN. Management of breast cancer in the genome era. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:153–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.061107.145152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawashima M, Fuwa N, Myojin M, Nakamura K, Toita T, Saijo S, Hayashi N, Ohnishi H, Shikama N, Kano M, Yamamoto M. A multi-institutional survey of the effectiveness of chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:569–583. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutierrez ME, Kummar S, Giaccone G. Next generation oncology drug development: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:259–265. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taulli R, Bersani F, Foglizzo V, Linari A, Vigna E, Ladanyi M, Tuschl T, Ponzetto C. The muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 blocks human rhabdomyosarcoma growth in xenotransplanted mice by promoting myogenic differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2366–2378. doi: 10.1172/JCI38075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor BC, Yuan JM, Shamliyan TA, Shaukat A, Kane RL, Wilt TJ. Clinical outcomes in adults with chronic hepatitis B in association with patient and viral characteristics: A systematic review of evidence. Hepatology. 2009;49:S85–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, Hudson MM, Kadin-Lottick NS, Kawashima TI, Leisenring WM, Meacham LR, Mertens AC, Mulrooney DA, Oeffinger KC, Packer RJ, Robison LL, Sklar CA. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2339–2355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD, Flygare SD, Bigham AW, Lee C, Shaffer T, Wong M, Bhattacharjee A, Eichler EE, Bamshad M, Nickerson DA, Shendure J. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, Boutell JM, Bryant J, Carter RJ, Keira Cheetham R, Cox AJ, Ellis DJ, Flatbush MR, Gormley NA, Humphray SJ, Irving U, Karbelashvili MS, Kirk SM, Li H, Liu X, Maisinger KS, Murray U, Obradovic B, Ost T, Parkinson ML, Pratt MR, Rasolonjatovo IM, Reed MT, Rigatti R, Rodighiero C, Ross MT, Sabot A, Sankar SV, Scally A, Schroth GP, Smith ME, Smith VP, Spiridou A, Torrance PE, Tzonev SS, Vermaas EH, Walter K, Wu X, Zhang L, Alam MD, Anastasi C, Aniebo IC, Bailey DM, Bancarz IR, Banerjee S, Barbour SG, Baybayan PA, Benoit VA, Benson KF, Bevis C, Black PJ, Boodhun A, Brennan JS, Bridgham JA, Brown RC, Brown AA, Buermann DH, Bundu AA, Burrows JC, Carter NP, Castillo N, Chiara ECM, Chang S, Neil Cooley R, Crake NR, Dada OO, Diakoumakos KD, Dominguez-Fernandez B, Earnshaw DJ, Egbujor UC, Elmore DW, Etchin SS, Ewan MR, Fedurco M, Fraser U, Fuentes Fajardo KV, Scott Furey W, George D, Gietzen KJ, Goddard CP, Golda GS, Granieri PA, Green DE, Gustafson DL, Hansen NF, Harnish K, Haudenschild CD, Heyer NI, Hims MM, Ho JT, Horgan AM, Hoschler K, Hurwitz S, Ivanov DV, Johnson MQ, James T, Huw Jones TA, Kang GD, Kerelska TH, Kersey AD, Khrebtukova I, Kindwall AP, Kingsbury Z, Kokko-Gonzales PI, Kumar A, Laurent MA, Lawley CT, Lee SE, Lee X, Liao AK, Loch JA, Lok M, Luo S, Mammen RM, Martin JW, McCauley PG, McNitt P, Mehta P, Moon KW, Mullens JW, Newington T, Ning Z, Ling Ng B, Novo SM, O'Neill MJ, Osborne MA, Osnowski A, Ostadan O, Paraschos LL, Pickering L, Pike AC, Pike AC, Chris Pinkard D, Pliskin DP, Podhasky J, Quijano VJ, Raczy C, Rae VH, Rawlings SR, Chiva Rodriguez A, Roe PM, Rogers J, Rogert Bacigalupo MC, Romanov N, Romieu A, Roth RK, Rourke NJ, Ruediger ST, Rusman E, Sanches-Kuiper RM, Schenker MR, Seoane JM, Shaw RJ, Shiver MK, Short SW, Sizto NL, Sluis JP, Smith MA, Ernest Sohna Sohna J, Spence EJ, Stevens K, Sutton N, Szajkowski L, Tregidgo CL, Turcatti G, Vandevondele S, Verhovsky Y, Virk SM, Wakelin S, Walcott GC, Wang J, Worsley GJ, Yan J, Yau L, Zuerlein M, Rogers J, Mullikin JC, Hurles ME, McCooke NJ, West JS, Oaks FL, Lundberg PL, Klenerman D, Durbin R, Smith AJ. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Wang W, Li R, Li Y, Tian G, Goodman L, Fan W, Zhang J, Li J, Zhang J, Guo Y, Feng B, Li H, Lu Y, Fang X, Liang H, Du Z, Li D, Zhao Y, Hu Y, Yang Z, Zheng H, Hellmann I, Inouye M, Pool J, Yi X, Zhao J, Duan J, Zhou Y, Qin J, Ma L, Li G, Yang Z, Zhang G, Yang B, Yu C, Liang F, Li W, Li S, Li D, Ni P, Ruan J, Li Q, Zhu H, Liu D, Lu Z, Li N, Guo G, Zhang J, Ye J, Fang L, Hao Q, Chen Q, Liang Y, Su Y, San A, Ping C, Yang S, Chen F, Li L, Zhou K, Zheng H, Ren Y, Yang L, Gao Y, Yang G, Li Z, Feng X, Kristiansen K, Wong GK, Nielsen R, Durbin R, Bolund L, Zhang X, Li S, Yang H, Wang J. The diploid genome sequence of an Asian individual. Nature. 2008;456:60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature07484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer A, Jung M, Kristiansen G, Lein M, Schrader M, Miller K, Erbersdobler A, Stephan C, Jung K. [MicroRNA in uro-oncology : New hope for the diagnosis and treatment of tumors?] Urologe A. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00120-009-2010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutesa L, Pierquin G, Janin N, Segers K, Thomee C, Provenzi M, Bours V. Germline PTPN11 missense mutation in a case of Noonan syndrome associated with mediastinal and retroperitoneal neuroblastic tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;182:40–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomez P, De Backer O, Bertrand M, De Plaen E, Boon T, Lucas S. An overview of the MAGE gene family with the identification of all human members of the family. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5544–5551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razmara M, Srinivasula SM, Wang L, Poyet JL, Geddes BJ, DiStefano PS, Bertin J, Alnemri ES. CARD-8 protein, a new CARD family member that regulates caspase-1 activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13952–13958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heichman KA, Roberts JM. The yeast CDC16 and CDC27 genes restrict DNA replication to once per cell cycle. Cell. 1996;85:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tugendreich S, Tomkiel J, Earnshaw W, Hieter P. CDC27HS colocalizes with CDC16HS to the centrosome and mitotic spindle and is essential for the metaphase to anaphase transition. Cell. 1995;81:261–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahuja A, Ying M, Evans R, King W, Metreweli C. The application of ultrasound criteria for malignancy in differentiating tuberculous cervical adenitis from metastatic nasopharyn-geal carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:391–395. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)83136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen PM, Brundell E, Starborg M, Hoog C. A subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex is a centromere-associated protein in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:468–476. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Meyts P, Gauguin L, Svendsen AM, Sarhan M, Knudsen L, Nohr J, Kiselyov VV. Structural basis of allosteric ligand-receptor interactions in the insulin/relaxin peptide family: implications for other receptor tyrosine kinases and G-protein-coupled receptors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1160:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pathan N, Marusawa H, Krajewska M, Matsuzawa S, Kim H, Okada K, Torii S, Kitada S, Krajewski S, Welsh K, Pio F, Godzik A, Reed JC. TUCAN, an antiapoptotic caspase-associated recruitment domain family protein overex-pressed in cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32220–32229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]