SUMMARY

The development of the precellular Drosophila embryo is characterized by exceptionally rapid transitions in gene activity, with broadly distributed maternal regulatory gradients giving way to precise on/off patterns of gene expression within a one hour window, between 2 and 3 hrs after fertilization [1]. Transcriptional repression plays a pivotal role in this process, delineating sharp expression patterns (e.g., pair-rule stripes) within broad domains of gene activation. As many as 20 different sequence-specific repressors have been implicated in this process, yet the mechanisms by which they silence gene expression have remained elusive [2]. Here we report the development of a method for the quantitative visualization of transcriptional repression. We focus on the Snail repressor, which establishes the boundary between the presumptive mesoderm and neurogenic ectoderm [3]. We find that elongating Pol II complexes complete transcription after the onset of Snail repression. As a result, moderately sized genes (e.g., the 22 kb sog locus) are fully silenced only after tens of minutes of repression. We propose that this “repression lag” imposes a severe constraint on the regulatory dynamics of embryonic patterning, and further suggest that post-transcriptional regulators, like microRNAs, are required to inhibit unwanted transcripts produced during protracted periods of gene silencing.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The zinc finger Snail repressor is one of the most extensively studied repressors in the Drosophila embryo. It has been implicated in a variety of developmental and disease processes, including epithelial-mesenchyme transitions and tumorigenesis [3-7]. Snail typically binds to repressor sites located near upstream activation elements within distal enhancers [8-9]. Repression might result from the “passive” inhibition of upstream activators, such as the failure of the activators to mediate looping to the core promoter. Alternatively, Snail might alter the chromatin state of the promoter region, resulting in diminished access of the Pol II transcription complex [2, 10]. Such repression mechanisms might cause a lag in gene silencing due to the continued elongation of Pol II complexes that were released from the promoter prior to the onset of repression (Fig. 1B). As in the case of the delay in the production of mature mRNAs after initiation (Fig. 1A), the lag in repression would be commensurate with the size of the gene, with large genes taking longer to silence than small genes. This can take a significant amount of time due to the surprisingly slow rate of Pol II elongation, just ~1 kb/min [11].

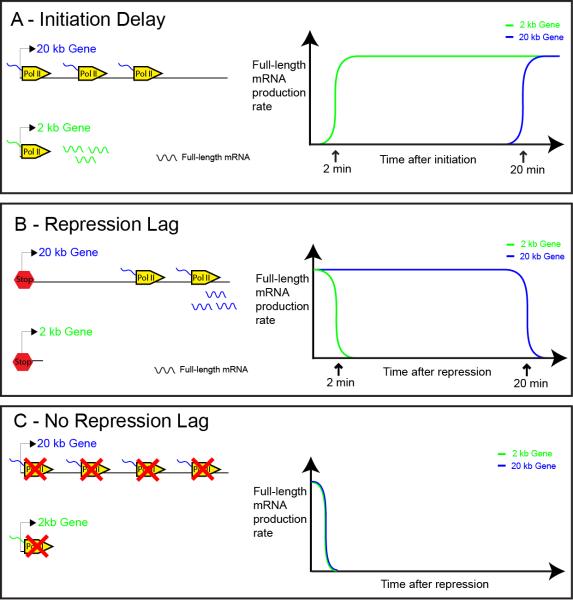

Figure 1. Schematic showing how the initiation of transcription and different schemes of repression affect the dynamics of full-length mRNA production.

A. Gene models showing the differences in the distribution of polymerase on a 20 kb and 2 kb gene and the amount of full-length mRNA produced some time after initiation. Not enough time has elapsed for Pol II complexes to reach the end of the 20 kb gene but the 2 kb gene is short enough such that multiple complexes have already reached it, allowing the production of full-length mRNA. This process is depicted in the graph showing the rate of full-length mRNA production as a function of time after initiation. It shows that there is a significantly longer delay before Pol II complexes can reach the end of the 20 kb gene (20 mins) and produce productive transcripts, compared to the 2 kb gene (2 mins). B. Gene models showing the differences in the distribution of polymerase on the two genes and the amount of full-length mRNA some time after transcriptional repression, assuming no new Pol II complexes are recruited to the gene after repression but that those on the gene finish elongating. Enough time has elapsed for Pol II complexes to transcribe the length of the 2 kb gene, and hence production of full-length transcripts have ceased. However, not enough time has elapsed for Pol II complexes to reach the end of the 20 kb gene, and so it is still producing full-length mRNA long after the initiation of repression. This process is depicted in the graph showing the rate of full-length mRNA production as a function of time after repression. It shows that there is a significantly longer delay before full-length mRNA production is repressed in the case of the 20 kb gene (20 min), compared to the 2 kb gene (2 min). C. Similar to B except that elongating Pol II complexes on the template are arrested or have their processivity attenuated when the genes are repressed. This would result in a rapid cessation in the production of full-length mRNA for both the 2 kb and 20 kb genes (assumed elongation speed of Pol II is 1 kb/min throughout).

Alternatively, elongating Pol II complexes might be arrested or released from the DNA template due to changes in chromatin structure and/or attenuation of Pol II processivity. Such mechanisms could lead to the immediate silencing of all genes regardless of size (see Fig. 1C). Recent studies have documented rapid changes in the chromatin structure across the entire length of genes, exceeding the rate of Pol II processivity [12]. Certain co-repressors in the Drosophila embryo (e.g., Groucho) are thought to mediate repression by a “spreading” mechanism that modifies chromatin over extensive regions [13]. Indeed, this type of mechanism has been invoked to account for the repression of the pair-rule gene, even-skipped (eve), by the gap repressor, Knirps (see below) [14]. The attenuation of Pol II elongation has been implicated in a variety of processes. For example, Pol II attenuation has been documented for the transcriptional repression of MYC [15]. Moreover, the activation of the HIV genome is regulated by Pol II processivity [16]. In an effort to distinguish these potential mechanisms we visualized the repression dynamics of several Snail target genes as they are silenced in the presumptive mesoderm of precellular embryos.

short gastrulation (sog) encodes an inhibitor of BMP/Dpp signaling that restricts peak Dpp signaling to the dorsal midline of cellularizing embryos [17-19]. The sog locus is ~22 kb in length and contains three large introns, including a 5’ intron that is ~10 kb in length and a 3’ intron that is ~5 kb in length (see Fig. 2C). The use of separate intronic hybridization probes permits independent detection of 5’ (see Fig. 2F) and 3’ (see Fig. 2G) sequences within sog nascent transcripts (Fig. 2). Individual nuclei are then false colored according to the probe combination they contain (see Fig. 2H).

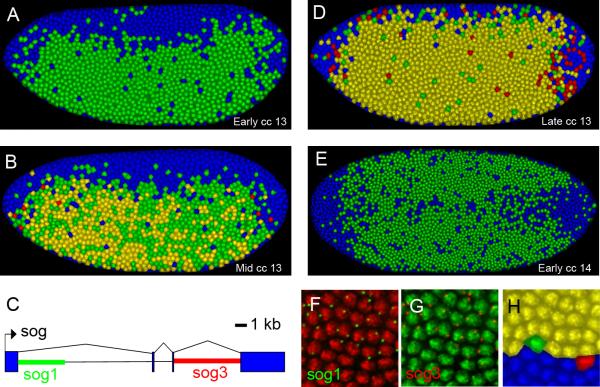

Figure 2. Time course of sog transcription from early cell cycle 13 to early cell cycle 14.

All embryos are oriented so that anterior is to the left. A. Lateral view of an embryo that is in the early stages of cc 13. Most of the nuclei contain intense dots of in situ hybridization signal that correspond to nascent transcripts. Only the 5’ intronic probe is detected (see C). The nuclei are false colored according to which combination of probes they contain (see F-H). B. Lateral view of an embryo that is midway through cc 13. Most of the nuclei show in situ signal for the 5’ probe and a subset of these also show staining for the 3’ probe. C. Simplified gene model for the sog transcript showing the location of the three biggest introns and the location of the sequences that the 5’ (green), sog1, and 3’ (red), sog3, intronic in situ probes hybridize to. D. Lateral view of an embryo that is in the late stages of cc 13. Most of the cells express both the 5’ and 3’ probes. E. Ventral view of an embryo that is in the early stages of cc 14. Only isolated 5’ probe is detected. F. Zoomed in section of a cc 14 embryo showing the expression of nascent transcript labeled by the 5’ probe in green. The nuclear stain has been false colored red to maximize the contrast. G. The same section as shown in F but with the 3’ probe labeled in red and the nuclear stain false colored green. H. The same section shown in F&G but after it has been processed with the segmentation algorithm. Isolated and paired nascent transcripts have been identified and nuclei false colored to reflect which combinations of probes are present in each nucleus. Nuclei that contain only isolated green, 5’, probes have been labeled in green. Nuclei that contain only isolated red, 3’, probes have been labeled in red. Nuclei that contain a coincident red and green dot have been labeled in yellow and nuclei that contain no probe have been labeled in blue.

sog exhibits synchronous activation at the onset of cc13, ~2 hrs after fertilization (see [20]). There is a lag between the time when nascent transcripts are first detected with the 5’ probe and subsequently cross-hybridize with both the 5’ and 3’ intronic probes (Fig. 2A,B). This lag is consistent with the established rates of Pol II elongation in flies, approximately 1.1-1.5 kb/min [11]. cc13 persists for ~20 min [21], and by the completion of this time window, most of the nuclei in ventral and lateral regions exhibit yellow staining, indicating the occurrence of multiple nascent transcripts containing 5’ and 3’ intronic sequences within each nucleus (Fig. 2D). There is little or no repression in ventral regions, presumably due to insufficient levels of the Snail repressor prior to cc14 [8, 22].

As shown previously, nascent transcripts are aborted during mitosis [23-24]. Consequently, only the 5’ hybridization probe detects sog nascent transcripts at the onset of cc14 (Fig. 2E). Moreover, a small number of nuclei (at the ventral midline) fail to exhibit nascent transcripts with either the 5’ or 3’ probe, suggesting repression by Snail. This repression becomes progressively more pronounced during cc14 (Fig. 3).

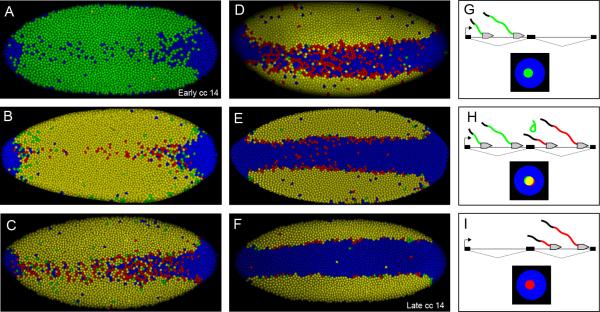

Figure 3. Time course of sog transcription from early cell cycle 14 to late cell cycle 14 with schematic explaining results.

All embryos are oriented so that anterior is to the left showing a ventral view. A. Embryo that is in the early stages of cc 14 the embryo is older than embryo shown in Fig. 1E. Most nuclei are only expressing the 5’ (green) probe, but a small number also express 3’ (red) probe. B. Within about 10 min of the first detection of sog nascent transcripts at the onset of cc14, most of the nuclei exhibiting sog expression stain yellow, indicating expression of both 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) intronic sequences. C. During the next several minutes, progressively more nuclei exhibit only 3’ (red) hybridization signals in ventral regions. D. This transition from yellow to red continues and culminates in a “red flash” where the majority of the ventral nuclei that contain nascent transcripts express only the 3’ (red) probe. E. As cc14 continues there is a progressive loss of staining in the presumptive mesoderm. F. Eventually sog nascent transcripts are lost almost entirely in the presumptive mesoderm in late cc14. G. Gene model depicting a gene like sog with multiple introns, where a 5’ (green) probe recognizes the mRNA coded for by the first intron and a 3’ (red) probe recognizes the mRNA coded for by the second intron. Initially only the 5’ (green) probe will hybridize to the nascent transcript. This is because not enough time has elapsed to transcribe the mRNA that the 3’ (red) probe hybridizes to. In an in situ nuclei where this has occurred will have a green dot at the site of nascent transcription. H. After enough time has elapsed for some Pol II complexes to reach the second intron labeled by the 5’ (red) probe, both probes will hybridize and will manifest as a yellow dot in a nucleus. Some of the individual transcripts associated with Pol II complexes that have made it well into the second intron will only hybridize the 3’ (red) probe because the 5’ (green) probe is co-transcriptionally spliced and degraded. I. If repression inhibits new polymerases from initiating transcription, but allow elongating polymerases to finish transcription, then after a time only the 3’ (red) probe will hybridize to nascent transcripts, because all the intronic sequences containing the 5’ (green) probe will have been spliced out and degraded. In an in situ, nuclei where this has occurred will have an isolated red dot at the site of nascent transcription.

Within about 10 min of the first detection of sog nascent transcripts at the onset of cc14 (Fig. 3A,G), most of the nuclei exhibiting sog expression stain yellow, indicating expression of both 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) intronic sequences (Fig. 3B,H). During the next several minutes, progressively more nuclei exhibit only 3’ (red) hybridization signals in ventral regions (Fig. 3C,I). This transition from yellow to red continues and culminates in a “red flash” where the majority of the ventral nuclei that contain nascent transcripts express only the 3’ (red) probe (Fig. 3D). As cc14 continues there is a progressive loss of staining in the presumptive mesoderm (Fig. 3E), and eventually sog nascent transcripts are lost entirely in the presumptive mesoderm (Fig. 3F).

These results suggest that after its release from the promoter, Pol II continues to elongate along the length of the sog transcription unit, even as Snail actively represses its expression in the mesoderm. The “red flash” observed during midcc14 represents partially processed sog nascent transcripts that have lost the 5’ intron (hence no green signals with the 5’ hybridization probe) but retain 3’ sequences (summarized in Fig. 3G-I). Previous studies are consistent with sequential processing of nascent transcripts, beginning with the removal of 5’ intronic sequences and concluding with the removal of 3’ introns [25]. As a control, two separate hybridization probes were used to label opposite ends of sog intron 1. As expected, there is no red flash since both hybridization signals are simultaneously lost when intron 1 is spliced (see Figs. S1; S2).

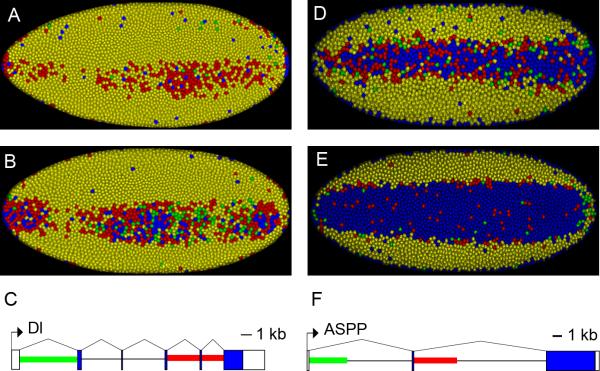

There is a ~20 minute lag between the onset of repression at early cc14 (Fig. 3B) and the complete silencing of sog expression in the presumptive mesoderm during mid to late cc14 (Fig. 3F). To determine whether this repression lag is a common feature of Snail-mediated gene silencing, we examined additional target genes, including ASPP, Delta, canoe and scabrous (sca). ASPP (Fig. 4D,E) encodes a putative inhibitor of apoptosis [26], while Delta (Fig. 4A,B) encodes the canonical ligand that induces Notch signaling. All four of these genes exhibit repression lag as they are silenced in the presumptive mesoderm of cc14 embryos (Fig. 4; Fig. S3)

Figure 4. Repression of Delta and ASPP transcription in the presumptive mesoderm.

All embryos are oriented so that anterior is to the left showing a ventral view. A. cc 14 embryo showing staining for Delta. Both the 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) probes (See C) hybridize to the nascent transcripts in most of the nuclei. However, in the ventral regions a number of nuclei only show the presence of the 3’ (red) probe consistent with repression. (See Fig 3) B. Older embryo showing more nuclei expressing the 3’ (red) probe, consistent with the continuation of Snail mediated repression. C. Simplified gene model for the Dl transcript showing the location of the biggest introns and the location of the mRNA sequences that the 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) intronic in situ probes hybridize to. D. cc 14 embryo showing staining for ASPP. Both the 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) probes (See F) hybridize to the nascent transcripts in most of the nuclei. However, in the ventral regions there is a significant amount of clearing showing a large number of nuclei that only show the presence of the 3’ (red) probe consistent with repression. (See Fig 3) E. Older embryo showing most of the nuclei in the mesoderm without any staining but some isolated nuclei expressing the 3’ (red) probe. This is consistent with the continuation of Snail mediated repression. C. Simplified gene model for the ASPP transcript showing the location of the biggest introns and the location of the mRNA sequences that the 5’ (green) and 3’ (red) intronic in situ probes hybridize to.

With the notable exception of Delta, the genes examined in this study contain promoter-proximal paused Pol II, as do most developmental patterning genes active in the precellular embryo [27]. Moreover, results from whole-genome Pol II binding assays indicate that these genes maintain promoter-proximal paused Pol II in the presumptive mesoderm as they are actively repressed by Snail. These findings are consistent with the observation that the segmentation gene, sloppy-paired-1, retains promoter-proximal paused Pol II even after being silenced by the ectopic expression of the Runt repressor [28]. Thus, the Snail repressor does not affect Pol II recruitment, but rather, inhibits the release of Pol II from the proximal promoter of paused genes. At every round of de novo transcription each Pol II complex at the pause site must receive an activation signal for its release into the transcription unit. We propose that the Snail repressor interferes with this signal, resulting in the retention of Pol II at the pause site.

It is currently unclear whether repression lag is a general feature of transcriptional silencing. A recent study suggests that the gap repressor, Knirps, reduces the processivity of Pol II complexes across the eve transcription unit [14]. Snail and Knirps might employ distinctive modes of transcriptional repression. Snail recruits the “short range” corepressor, CtBP [29], while Knirps recruits either CtBP or the “long-range” corepressor, Groucho [30]. When bound to certain cis-regulatory elements within the eve locus, Knirps recruits Groucho, which might propagate a repressive chromatin structure. In contrast, Snail-CtBP might interfere with the release of Pol II from the proximal promoter, as discussed above. There is a considerable difference in the lengths of the genes examined in the two studies. The eve transcription unit is only 1.5 kb in length, less than a tenth the size of sog. In fact, many patterning genes active in the early fly embryo contain small transcription units, just a few kb in length. Small transcription units offer dual advantages in rapid patterning processes: little or no lag in activation or repression.

All five Snail target genes examined in this study exhibit Pol II elongation after the onset of repression. The number of transcripts produced during repression lag depends on the Pol II density across the transcription unit at the onset of repression Pol II binding assays (e.g., ChIP-chip, ChIP-Seq, and Gro-Seq) suggest that there are at least several Pol II complexes per kb [27]. This estimate is based on comparing the total amount of Pol II within these genes to that present at the promoter of the uninduced hsp 70 gene, for which there are accurate measurements. As a point of reference the Pol II density on induced heat shock genes is one complex per 75-100 bp [31], which is comparable to the footprint size, ~50 bp, of an elongating Pol II complex [32]. Thus, something like ~50 (or more) sog transcripts may be produced in a diploid cell after the onset of Snail repression. This represents a significant fraction of the steady-state expression of a typical patterning gene (~200 transcripts per cell [33]).

Repression lag could impinge on a number of patterning processes, such as Notch signaling. The specification of the ventral midline of the CNS depends on the activation of Notch signaling in the ventral-most regions of the neurogenic ectoderm [34]. Sca products somehow facilitate the activation of the Notch receptor [35], and repression lag could potentially disrupt this process by producing high steady state levels of Sca in the mesoderm where Notch is normally inactive. Similar arguments might apply to the unwanted accumulation of Delta products in the mesoderm. Perhaps microRNAs are required to inhibit these transcripts, and thereby facilitate localized activation of Notch signaling. Indeed, miR-1 is expressed in the presumptive mesoderm, at the right time and place to regulate Sca and/or Delta [36], and is known to be able to target Delta transcripts [37]. Repression lag is potentially quite severe for Hox genes, particularly Antp and Ubx, which contain large transcription units (100-75 kb) that could take over an hour to silence after the onset of repression. It is conceivable that miRNAs encoded by the miR-iab4 gene, which are known to target Antp and Ubx transcripts [38,39], might inhibit post-repression transcripts.

The precellular Drosophila embryo possesses a number of inherently elegant features for the detailed visualization of differential gene activity in development. Indeed, such studies were among the first to highlight the importance of transcriptional repression in the delineation of precise on/off patterns of gene expression. Here we extend this rich tradition of visualization by providing the first dynamic view of gene silencing. The key feature of our method is the use of sequential 5’ and 3’ intronic probes to distinguish nascent transcripts produced by Pol II complexes shortly after their release from the promoter vs. “mature” Pol II elongation complexes that have already transcribed 5’ intronic sequences. We show that elongating Pol II complexes complete transcription after the onset of Snail repression and as a result, moderately sized genes are fully silenced only after a significant lag. We suggest that this repression lag represents a previously unrecognized constraint on the regulatory dynamics of the precellular embryo.

Experimental Procedures

Fluorescent in situ hybridization and quantitative imaging methods

Fluorescent in situ hybridization was performed on yw embryos as described in [31], with minor modifications. Embryos were imaged on a Carl Zeiss LSM 700 Laser Scanning microscope as 20-25 section z-stacks through the nuclear layer at 1/2 micron intervals, using a Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.8, WD=0.55 mm objective lens. Image stacks were maximum intensity projected and computationally segmented to localize and count nuclei and in situ probes. Nascent transcripts were then assigned to nuclei. In order to visualize transcriptional state individual nuclei have been false colored to reflect the transcriptional state as determined by the segmentation of the in situ probes. Extensive controls were conducted to show that nascent transcripts could be detected and classified with high accuracy. More details on the image analysis, segmentation and in situ protocol are included in the Supplemental methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Chiahao Tsui for technical support, Mounia Lagha, Valerie Hilgers, Alistair Boettiger, Vivek Chopra, and other members of the Levine lab as well as Nipam Patel for discussions and helpful suggestions. J.B. is the recipient of a Berkeley Fellowship. This work was funded by a grant from the NIH (GM46638) to M.L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lawrence PA, Struhl G. Morphogens, Compartments and Pattern: Lessons from Drosophila? Cell. 1992;85:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payankaulam S, Li LM, Arnosti DN. Transcriptional Repression: Conserved and Evolved Features. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:R764–R771. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosman D, Ip YT, Levine M, Arora K. Establishment of the mesoderm-neuroectoderm boundary in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 1991;254:118–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1925551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasai Y, Nambu JR, Lieberman PM, Crews ST. Dorsalventral patterning in Drosophila: DNA binding of snail protein to the single-minded gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:3414–3418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulay JL, Dennefeld C, Alberga A. The Drosophila developmental gene snail encodes a protein with nucleic acid binding fingers. Nature. 1987;330:395–398. doi: 10.1038/330395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry MW, Boettiger AN, Bothma JP, Levine M. Shadow Enhancers Foster Robustness of Drosophila Gastrulation. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moody SE, Perez D, Pan TC, Sarkisian CJ, Portocarrero CP, Sterner CJ, Notorfrancesco KL, Cardiff RD, Chodosh LA. The transcriptional repressor snail promotes mammary tumor recurrence. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip YT, Park RE, Kosman D, Bier E, Levine M. The dorsal gradient morphogen regulates stripes of rhomboid expression in the presumptive neuroectoderm of the drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1728–1739. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeitlinger J, Zinzen RP, Stark A, Kellis M, Zhang H, Young RA, Levine M. Whole-genome ChIP-chip analysis of Dorsal, Twist, and Snail suggests integration of diverse patterning processes in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2007;21:385–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.1509607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deckert J, Struhl K. Histone Acetylation at Promoters Is Differentially Affected by Specific Activators and Repressors. Mol Cel Biol. 2001;21:2726–2735. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2726-2735.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardehali MB, Lis JT. Tracking rates of transcription and splicing in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1123–1124. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1109-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petesch SJ, Lis JT. Rapid, transcription-independent loss of nucleosomes over a large chromatin domain at Hsp70 loci. Cell. 2008;134:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez CA, Arnosti DH. Spreading of a corepressor linked to action of long-range repressor hairy. Mol Cel Biol. 1998;28:2792–2802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01203-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li LM, Arnosti DH. Long- and Short-Range Transcriptional Repressors Induce Distinct Chromatin States on Repressed Genes. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laspia MF, Rice AP, Mathews MB. HIV-1 Tat protein increases transcriptional initiation and stabilizes elongation. Cell. 1989;59:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francois V, Solloway M, O'Neill JW, Emery J, Bier E. Dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo depends on a putative negative growth factor encoded by the short gastrulation gene. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2602–2616. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podos SD, Ferguson EL. Morphogen gradients - New insights from DPP. Trends in Genet. 1999;15:396–402. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashe HL, Levine M. Local inhibition and long-range enhancement of Dpp signal transduction by Sog. Nature. 1999;398:427–431. doi: 10.1038/18892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boettiger AN, Levine M. Synchronous and stochastic patterns of gene activation in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 2009;325:471–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1173976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foe VE, Alberts BM. Studies of nuclear and cytoplasmic behavior during the five mitotic cycles that precede gastrulation in drosophila embryogeneis. J. Cell. Sci. 1983;61:31–71. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray S, Szymanski P, Levine M. Short-range repression permits multiple enhancers to function autonomously within a complex promoter. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1829–1838. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shermoen AW, O'Farrel PH. Progression of the cell cycle through mitosis leads to abortion of nascent transcripts. Cell. 1991;67:303–310. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothe M, Pehl M, Taubert H, Jackle H. Loss of gene function through rapid mitotic cycles in the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1992;359:156–159. doi: 10.1038/359156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh J, Padgett RA. Rates of in situ transcription and splicing in large human genes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1128–1133. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langton PF, Colombani J, Aerne BL, Tapon N. Drosophila ASPP regulates C-terminal Src kinase activity. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:773–782. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeitlinger J, Stark A, Kellis M, Hong J-W, Nechaev S, Adelman K, Levine M, Young RA. RNA polymerase stalling at developmental control genes in the Drosophila embryo. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1512–1516. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Lee C, Gilmour DS, Gergen JP. Transcription elongation controls cell fate specification in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1031–1036. doi: 10.1101/gad.1521207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nibu Y, Zhang H, Levine M. Interaction of short-range repressors with Drosophila CtBP in the embryo. Science. 1998;280:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payankaulam S, Arnosti DN. Groucho corepressor functions as a cofactor for the Knirps short-range transcriptional repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:17314–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Brien T, Lis JT. Rapid changes in Drosophila transcription after an instantaneous heat shock. Mol Cel Biol. 1993;13:3456–63. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rice GA, Chamberlin MJ, Kane CM. Contacts between mammalian RNA polymerase II and the template DNA in a ternary elongation complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:113–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pare A, Lemons D, Kosman D, Beaver W, Freund Y, McGinnis W. Visualization of Individual Scr mRNAs during Drosophila Embryogenesis Yields Evidence for Transcriptional Bursting. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:2037–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowden J, Levine M. The Snail repressor positions Notch signaling in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2002;129:1785–1793. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.7.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Fetchko M, Lai ZC, Baker NE. Scabrous and Gp150 are endosomal proteins that regulate Notch activity. Development. 2003;130:2819–2827. doi: 10.1242/dev.00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biemar F, Zinzen R, Ronshaugen M, Sementchenko V, Manak JR, Levine MS. Spatial regulation of microRNA gene expression in the Drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:15907–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507817102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon C, Han Z, Olson EN, Srivastava D. MicroRNA1 influences cardiac differentiation in Drosophila and regulates Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:18986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509535102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stark A, Bushati N, Jan CH, Kheradpour P, Hodges E, Brennecke J, Bartel DP, Cohen SM, Kellis M. A single Hox locus in Drosophila produces functional microRNAs from opposite DNA strands. Genes Dev. 2008;22:8–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.1613108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ronshaugen M, Biemar F, Piel J, Levine M, Lai EC. The Drosophila microRNA iab-4 causes a dominant homeotic transformation of halteres to wings. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2947–2952. doi: 10.1101/gad.1372505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.