Abstract

This study examined the relations between facial attractiveness, peer victimization, and internalizing problems in early adolescence. We hypothesized that experiences of peer victimization would partially mediate the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems. Ratings of attractiveness were obtained from standardized photographs of participants (93 girls, 82 boys). Teachers provided information regarding peer victimization experiences in sixth grade, and seventh grade teachers assessed internalizing problems. Attractiveness was negatively correlated with victimization and internalizing problems. Experiences of peer victimization were positively correlated with internalizing problems. Structural equation modeling provided support for the hypothesized model of peer victimization partially mediating the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems. Implications for intervention programs and future research directions are discussed.

“Beauty is the promise of happiness” (Stendhal, 1822, as cited in Gorham, 2005, pp. 1–2).

Attractiveness may confer numerous social advantages. Attractive adults are treated more positively by both known and unknown interaction partners (Langlois et al., 2000) and are more sought after as romantic partners than are less attractive individuals (Walster, Aronson, Abrahams, & Rottman, 1966). Attractive individuals also enjoy greater occupational prestige (Umberson & Hughes, 1987) and higher salaries than their less attractive counterparts (Hamermesh & Biddle, 1994).

Favorable outcomes associated with attractiveness do not suddenly manifest themselves in adulthood; rather, they first appear in infancy. Adults perceive attractive infants to be more likable, less disruptive (Stephan & Langlois, 1984), and more competent than unattractive infants (Ritter, Casey, & Langlois, 1991). Infants are treated differently depending on their attractiveness and mothers even behave more affectionately toward their own attractive infants (Langlois, Ritter, Casey, & Sawin, 1995). Favorable outcomes follow attractive individuals throughout development. Attractive preschoolers, children, and adolescents receive more positive treatment by parents (Bergman, 2005; Elder, Van Nguyen, & Caspi, 1985), teachers (Kenealy, Frude, & Shaw, 1988; Lerner, Delaney, Hess, Jovanovic, & von Eye, 1990), and peers (Smith, 1985; Vaughn & Langlois, 1983).

Differential treatment as a function of attractiveness is likely internalized, and will in turn influence adjustment in accord with Stendhal’s claim; attractive individuals may be happier and better adjusted in response to preferential treatment, whereas unattractive individuals may be depressed and experience greater maladjustment as a result of appearance-based discrimination. Although this hypothesis has been articulated by several researchers (e.g., Burns & Farina, 1992; Patzer & Burke, 1988), few empirical studies have examined this issue. The current investigation examines the link between attractiveness and adjustment in early adolescence. Specifically, we hypothesize that less attractive adolescents are more likely to be victimized by their peers and that these negative peer experiences result in internalizing problems.

Several theoretical perspectives suggest there should be a link between appearance and adjustment. Lewinsohn’s (1974) reinforcement theory posits that low rates of social reinforcement are associated with depression. Given that attractiveness appears positively related to social reinforcement, Noles, Cash, and Winstead (1985) propose that depression may be more common among unattractive individuals in accordance with Lewinsohn’s theory because they may experience less reinforcement.

Cooley’s looking glass-self theory posits that self-views are a product of our social worlds; he writes that “there is no sense of ‘I,’ as in pride or shame, without its correlative sense of you, or he, or they” (Cooley, 1902, p.151). According to this theoretical perspective, we learn about the self by observing others’ reactions to us and thus, “self-perception is an internalization of how we are seen by others” (Yeung & Martin, 2003, p.846). Applying this viewpoint to the attractiveness literature, unattractive individuals should feel poorly about themselves as a result of appearance-based discrimination.

Similarly, in his theory of peer rejection, Coie (1990) suggests that appearance serves as a non-behavioral contributor to peer difficulties. This theory is a stage theory (Coie, 1990; Coie & Cillessen, 1993), and during the emergent status phase a number of behavioral or non-behavioral factors can lead to children emerging as rejected. Unattractive children may emerge as rejected whereas attractive children emerge as popular. Peers may shun unattractive children for fear of being associated with them and gravitate toward attractive children with the hope that these affiliations will raise their social status. The manner in which children respond to appearance-based victimization, such as reacting aggressively, may be a further risk factor for peer rejection. Social cognitive processes influence behavior in these situations, and rejected children may display deficits in social information processing. During the maintenance phase, the experience of rejection becomes incorporated into the unattractive child’s social identity and finally, during the consequences phase, the unattractive child may experience difficulties such as internalizing problems as the result of being rejected.

Despite prior theoretical support, this is one of the first investigations of attractiveness, peer victimization, and childhood adjustment. Although there are no published studies empirically examining the relationship between independent ratings of attractiveness and victimization, peer researchers have long hypothesized that attractiveness confers an advantage in peer relations (Coie, 1990), and research findings provide support for this conjecture (Dion, 1973; Lerner & Lerner, 1977). We discuss this research below and speculate as to why unattractive adolescents may be likely victimized by peers. We then describe how victimization confers risk for psychopathology, and discuss the relationship between attractiveness and adjustment.

Attractiveness and Peer Relations

Social preferences for attractive individuals emerge early in development. Infants respond more positively to and withdraw less frequently from an attractive stranger (Langlois, Roggman, & Reiser-Danner, 1990). By preschool age, young children make behavioral attributions about unknown peers that are consistent with the “beauty is good” stereotype (Dion, 1973), which is the bias to attribute positive traits to attractive people and negative traits to unattractive people (Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972). Attractive peers are perceived to be friendlier and exhibit other positive behaviors whereas unattractive children are believed to display negative social behaviors such as aggression (Dion, 1973).

Children’s peer judgments and preferences are often congruent with the beauty is good stereotype. In a study by Dion (1973) utilizing a sociometric picture board task, preschoolers were asked to indicate whom they thought would be a good potential friend and whom they believed would be a bad potential friend from a group of unknown peers. The pictures presented were selected from a larger pool of images based on attractiveness ratings of adult judges using a 1 (very unattractive) to 5 (very attractive) Likert scale. Preschoolers preferred attractive peers and disliked unattractive peers. These findings have been replicated and extended to older samples (Kleck, Richardson, & Ronald, 1974). Further, similar relationships between attractiveness and sociometric status seem to exist for children who are acquainted with one another. Attractive peers are rated as more popular than unattractive peers by their classmates, both in studies with preschoolers in which ratings of attractiveness were obtained (Vaughn & Langlois, 1983) and in studies with older children relying on peer reports of attractiveness (Dijkstra, Lindenberg, Verhulst, Ormel, & Veenstra, 2009).

Although studies demonstrate that individuals of all ages hold favorable expectations for attractive members of both sexes and prefer them as social partners (Langlois et al., 2000), little empirical work has examined differences in peer treatment as a function of attractiveness. Observational studies in preschools find that young children behave in a more affiliative fashion when interacting with a peer of similar attractiveness (Langlois & Downs, 1979) and behave more prosocially toward attractive females (Smith, 1985).

We hypothesize that less attractive adolescents may be at elevated risk for peer victimization. Less attractive adolescents may be especially easy targets for individuals seeking to disparage others because facial appearance is an overt characteristic visible to all interaction partners. Although there is no published research examining the relation between peer victimization and independent measures of attractiveness, self-report data suggest that unattractive adolescents may be at greater risk for peer victimization. According to a nationally representative survey of American youth, approximately twenty percent of sixth through tenth grade students report being frequently belittled about their looks or speech, both of which are easily observable traits (Nansel et al., 2001). Another study of British youth found that some victims reported being bullied as a result of personal characteristics such as their appearance (Smith, Talamelli, Cowie, Naylor, & Chauhan, 2004). It is important to note, however, that these findings are based on self-report alone rather than independent assessments of attractiveness.

Additional research has examined the relation between self-perceived attractiveness and indirect victimization (Leenaars, Dane, & Marini, 2008). High school students reported on their experiences of indirect victimization and rated their own attractiveness on a 4-point scale ranging from “not good looking” to “very good looking”. Leenaars and colleagues (2008) found that self-perceived attractiveness interacted with gender and grade in the prediction of victimization. Self-perceived attractiveness appeared to protect boys from peer victimization. Girls who believed they were highly attractive, however, were at risk for victimization; attractive girls may be subject to peer maltreatment as a result of competition for romantic partners. For younger students, self-perceived attractiveness appeared to serve as a protective factor from victimization; attractiveness was associated with decreased odds of peer maltreatment for this group. The relation between victimization and self-perceived attractiveness was not significant for older students.

Replication of these results is needed with independent measures of attractiveness given that “the relationship between actual attractiveness and self-evaluation is a good deal less than perfect” (Kenealy, Gleeson, Frude, & Shaw, 1991, p. 52). The term independent is used to recognize that a large group of individuals is rating photographs of unknown persons (Rosen & Underwood, 2010), and thus raters are not influenced by interaction history or information on participants’ non-physical characteristics (e.g., intelligence, personality, family income). Research suggests that there is not a strong correspondence between self-perceived attractiveness and independent ratings of attractiveness (Kenealy et al., 1991; Krantz, Friedberg, & Andrews, 1985). Some individuals overestimate their attractiveness whereas others underestimate their attractiveness (Kenealy et al., 1991; Noles et al., 1985). The current study differs from past research (Leenaars et al., 2008) by examining peer victimization as a function of overt appearance rather than self-perceived appearance.

The current study is the first known investigation to examine the relation between independent measures of facial attractiveness and peer victimization. Stereotypic attributions congruent with the beauty is good stereotype may lead to exclusion or disparagement of less attractive individuals for fear that they may decrease the adolescents’ social standing among peers (Eder, 1985). For these reasons, unattractive adolescents may be chronic victims of peer maltreatment.

Victimization and Adjustment

Victimization can be defined as repeated exposure to peer maltreatment (Olweus, 1995). This maltreatment can include behaviors such as relationship manipulation, social exclusion, malicious gossip, verbal insults/teasing, and even physical attacks (Crick, Casas, & Nelson, 2002; Harrist & Bradley, 2003; Lee, Baillargeon, Vermunt, Wu, & Tremblay, 2007; Paquette & Underwood, 1997; Roth, Coles, Heimberg, 2002). Victimization may involve bully-victim dynamics in which there is an imbalance of power such that the victim cannot easily defend himself/herself (Olweus, 1995). Bully-victim problems have received increased research attention because they pose a pervasive problem for many youth (Berger, 2007).

Although estimates vary, studies indicate that approximately ten percent of children are frequently victimized by their peers (Olweus, 1995; Perry, Kusel, Perry, 1988; Rigby & Slee, 1991). Some children emerge as victims of peer maltreatment as early as preschool (Crick, Casas, & Ku, 1999). There may be fluctuations in victimization status throughout development, but extreme peer maltreatment appears constant for certain children (Kochenderfer-Ladd & Wardrop, 2001; Kumpulainen, Rasanen, & Henttonen, 1999; Scholte, Engels, Overbeek, de Kemp, & Haselager, 2007).

Adolescents subject to peer victimization are at greater risk for maladjustment, especially internalizing symptoms. According to sixth graders’ daily diary reports at the end of the school day, youth feel humiliated by peer victimization (Nishina & Juvonen, 2005). Victimized adolescents also report feeling lonelier, being more socially anxious (Storch, Brassard, & Masia-Warner, 2003; Storch & Masia-Warner, 2004), and having lower self-esteem (Paquette & Underwood, 1999; Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001) than non-victimized youth.

Peer victimization is also associated with depression and this appears to be a robust finding in the literature (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Prinstein et al., 2001). A large scale study of 2,342 high school students found that frequently victimized youth were at risk for depression, suicidal thoughts, and suicidal attempts (Brunstein Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould, 2007).

Peer victimization may also be related to physical symptoms. For sixth graders, experiences of peer victimization in the fall of the school year predicted somatic complaints in the spring (Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005). Nishina et al. offered two potential explanations for these results. First, victimization may be a chronic, stressful experience that suppresses the immune system and leads to illness. Alternatively, adolescents may report feeling poorly in order to miss school and escape being bullied.

In addition to the internalizing problems described above, victimization is associated with other negative outcomes including externalizing problems (Sullivan, Farrell, Kliewer, 2006) and school maladjustment (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). According to adolescent self-reports, victimization is positively related to levels of aggression, delinquency, and substance use (Sullivan et al., 2006). Victimization is negatively related to school adjustment as indexed by school liking (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996), grade point average, and standardized test scores (Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & Toblin, 2005). Victimized youth may display different patterns of adjustment difficulties with some experiencing problems in multiple domains (Hanish & Guerra, 2002).

Because of the negative outcomes associated with victimization, much research has examined factors that place youth at risk in the hopes of developing effective interventions (Craig & Pepler, 2003). Certain behavioral factors may place children at risk for victimization. Aggressiveness as rated by teachers is positively related to victimization (Hanish & Guerra, 2000). Observational study of peer interactions provides convergent evidence for the predictive validity of aggression in relation to victimization; aggressive responses to bullying tended to exacerbate the situation (Mahady Wilton, Craig, & Pepler, 2000). Other observational research suggests that submissive behavior also predicts victimization (Schwartz, Dodge, & Coie, 1993). Additionally, there are social risk factors such as lack of friends, which are positively related to victimization. These social risk factors interact with other risk factors; supportive friends can act as a buffer against peer victimization even in the presence of behavioral risk factors (Hodges, Malone, & Perry, 1997). There may also be appearance-based risk factors for peer victimization. There is limited research on appearance-based risk factors with the extant literature focusing on the positive association between physical weakness and victimization (Hodges & Perry, 1999) and weight and victimization (Neumark-Sztainer, Story, & Faibisch, 1998). We hypothesize that less attractive adolescents are victimized more frequently by their peers, and thus experience greater internalizing difficulties than do their more attractive peers. Even though research has yet to examine peer maltreatment as a potential mediator between attractiveness and adjustment, several studies have examined the association between appearance and adjustment.

Attractiveness and Adjustment

Little developmental research has examined the associations between attractiveness and adjustment. A notable exception is research by Lerner and colleagues that examined the relationship between appearance and adjustment in children and early adolescents. Standardized photographs of each participant were presented to a large group of college students who provided ratings of attractiveness using a 1 to 5 Likert scale. A mean attractiveness rating was calculated for each participant and used in subsequent analyses (Lerner & Lerner, 1977; Lerner et al., 1990). Teachers rated their more attractive students as better adjusted in the educational environment than their less attractive students (Lerner & Lerner, 1977). In later studies they collected parents’ ratings of their children’s psychosocial functioning and found that unattractive adolescents demonstrated more problematic behaviors as assessed by parent ratings (Lerner et al., 1991).

The majority of the research linking attractiveness to maladjustment has involved adult psychiatric inpatients. Institutionalized mental patients were rated as more unattractive than a control group (Farina et al., 1977). Even prior to hospitalization, inpatients were rated as less attractive than their peers based on high school yearbook photographs (Napoleon, Chassin, & Young, 1980). Objective ratings of patient attractiveness were also associated with prior hospitalization such that more unattractive patients had more severe past histories (Archer & Cash, 1985). Following discharge from the hospital, attractive patients experienced better outcomes as evidenced by longer periods without institutional care and higher ratings of adjustment (Farina, Burns, Austad, Bugglin, & Fischer, 1986).

In an extension of the study of appearance and adjustment beyond hospitalized inpatients to a nationally representative sample of the United States’ population, attractive individuals reported being better adjusted than unattractive individuals (Umberson & Hughes, 1987). Attractive individuals experienced more positive affect and reported being happier and more satisfied than their unattractive counterparts. Unattractive individuals, on the other hand, reported greater negative affect and more stress than did attractive individuals (Umberson & Hughes, 1987).

Current Research

The current research investigates whether differential treatment as a function of appearance mediates the relationship between attractiveness and adjustment. In particular, we evaluate whether less attractive adolescents are frequent victims of peer victimization. Further, we examine whether frequent victimization of less attractive adolescents results in greater internalizing difficulties.

To test these research questions, we first obtained standardized photographs of early adolescents. We then collected ratings of facial attractiveness from the photographs. We asked the adolescents’ sixth grade teachers to report the degree to which the adolescents experienced peer victimization; teachers rated how frequently adolescents experienced physical, verbal, and general peer maltreatment. Seventh grade teachers reported on adolescents’ internalizing problems.

The current study, like many previous investigations of victimization, focuses on early adolescents (e.g., Nishina & Juvonen, 2005) because the prevalence of peer maltreatment may be highest around sixth grade and then drop in later adolescence (Kaufman et al., 2000; Nansel et al., 2001). Similar to prior longitudinal studies on peer victimization and adjustment (e.g., Nishina et al., 2005), our assessments spanned 1-year; however, rather than collecting data at the start and end of the school year, we collected teacher reports in the spring of sixth and seventh grades in order to avoid problems associated with shared-method variance.

We first hypothesized that adolescents rated as low on attractiveness would be subject to more peer victimization than adolescents rated as high on attractiveness. Secondly, we expected that less attractive adolescents would have more internalizing difficulties than their more attractive counterparts and those experiences of peer victimization would partially mediate the observed relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems. We did not, however, expect peer victimization to fully account for the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems because unattractive adolescents may also be treated more negatively by many different types of interaction partners besides peers including, parents (e.g., Bergman, 2005; Elder et al., 1985) and teachers (e.g., Kenealy et al., 1988). Last, we expected that these relationships would hold for both boys and girls. This hypothesis is consistent with the results of a recent meta-analysis finding that gender does not moderate the relationship between attractiveness and differential treatment; attractive males and females were treated more favorably than their unattractive counterparts (Langlois et al., 2000). Similarly, both males and females seem to suffer when faced with peer victimization (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Nishina et al., 2005). Although we did not anticipate differences, we tested for the effects of gender in all analyses.

Method

Participants

The data presented in this study were collected as part of a longitudinal study on the development and outcomes of social aggression. Children were originally recruited from third grade classrooms in a diverse suburban school district and were followed through seventh grade. During sixth grade, children were invited to take part in the picture taking portion of the study following their yearly laboratory visit. Photographs were collected from over 80% of the 213 sixth graders who participated in the larger longitudinal study. There were no significant differences for victimization or internalizing problems between the group that was photographed and the group that was not photographed. Participants who were photographed included 93 girls and 82 boys. Parents identified the ethnicity of child participants as: European American (n = 105, 60%), Mexican American (n = 34, 19.4%), African American (n = 28, 16%), and other (n = 8, 4.6%).

The participants’ sixth and seventh grade teachers were also invited to participate in this study. Teachers were contacted by e-mail or in person to participate in the study. Teacher ratings were collected for 159 target children in sixth grade and 139 target children in seventh grade.

Procedures

During the children’s third grade year, active parental consent was obtained upon initial recruitment into the longitudinal study. Researchers visited elementary school classrooms and sent consent forms home. Of the letters distributed, approximately 55% were returned with consent to participate for the duration of the study. This rate of consent is commensurate with many similar studies that report consent rates for research conducted in school classrooms (Betan, Roberts, & McCluskey-Fawcett, 1995; Sifers, Warren, Puddy, & Roberts, 2002). However, our consent rate is lower than that of many school-based studies of peer victimization (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2005), likely because we asked parents to consent to participate in a series of laboratory visits over the course of five years. Because observing social processes related to social aggression was a primary goal of the longitudinal study, children participated in yearly laboratory visits that were scheduled during the month of their birthday and were compensated $25 for each visit.

The data presented for the current study were collected from target children during their sixth grade year. The children were photographed at this time, and although only these photographs are relevant to the current study, the children also completed questionnaires and observational tasks related to the larger longitudinal study. The photographs were taken in a standardized fashion; each participant was asked to pose with a neutral expression in front of a blue backdrop with a draped sheet to mask clothing cues (Langlois & Roggman, 1990). We equated for various image characteristics such as brightness using Adobe Photoshop™.

Prior to taking the pictures, we presented the children’s parents with comprehensive written information on how we planned to use the photographs. We described our ratings procedure to parents detailing that undergraduate students would view the child’s picture as part of a larger group of images. Although the photographs were used to obtain judgments of attractiveness, we assured parents that we would store the pictures in a secure location and not provide others with access to these images. Parents were then asked to provide separate written consent for their child’s participation in the picture-taking portion of the study.

We presented the photographs to 120 undergraduate men and women at a public university in the southern United States who rated the images for attractiveness using a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = very unattractive, 5 = very attractive). Our methodology is similar to that employed in many other investigations of attractiveness; researchers commonly present photographs to groups of undergraduate students who rate these images using a Likert scale. An average rating is then calculated for each person photographed and used as a measure of his or her attractiveness (e.g., Griffin & Langlois, 2006; Lerner & Lerner, 1977; Ramsey & Langlois, 2002).

This method is highly reliable for obtaining attractiveness ratings of both children and adults (e.g., Griffin & Langlois, 2006; Ramsey & Langlois, 2002). Individuals within and across cultures agree on who is and who is not attractive (Langlois et al., 2000). Similarly, adults and children demonstrate high agreement in attractiveness ratings and even young infants show visual preferences for faces that have been rated as attractive by adults (Langlois et al., 1987). In this study, we assessed the reliability using the method espoused by Vaughn and Langlois (1983) and treated each undergraduate rater as an item and each adolescent picture as a subject. The resulting Cronbach’s alpha was .99 which was commensurate with that reported by Vaughn and Langlois (1983).

We considered attractiveness as a continuous variable in our analyses as reported below. However, to check the robustness of our results we re-estimated our models with a binary attractiveness variable based on a median split. The results were consistent when considering attractiveness as binary variable, and thus we only report the findings of analyses that considered attractiveness as a continuous variable.

Teachers provided measures of the target child’s social experiences and adjustment. At the end of the sixth and seventh grade school years, questionnaires were delivered to the children’s teachers and collected upon completion. Teachers were compensated $25 per child. For the purposes of the current study, sixth grade teachers completed the Teacher Report of Victimization (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002) and the Children’s Social Behavior Scale – Teacher Form (Crick, 1996), and seventh grade teachers completed the Child Behavior Checklist – Teacher Report Form (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). These measures are discussed in detail below.

We chose to invite teachers to provide ratings of victimization and adjustment in the current study because of the efficiency and reliability offered by this method (Cillessen, Terry, Coie, & Lochman, 2002; Henry, Miller-Johnson, Simon, & Schoeny, 2006; Merrell, Buchanan, & Tran, 2006). There is agreement between teacher ratings of victimization with both peer and self reports, which has lead some peer relations experts to conclude that “teachers appear to be very sensitive observers of the social worlds of their students” (Putallaz et al., 2007, p. 544).

Measures

Teacher Report of Victimization

We administered the Teacher Report of Victimization (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002) to sixth grade teachers. Teachers rated the extent to which five key items embedded among eight filler items described the experiences of the target child using a 1–3 scale (1 = seldom, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = often). Responses to the following key items were averaged to create a victimization score: This child (1) is picked on by other children, (2) is called names by peers, (3) has peers who say negative things about him or her to other children, (4) is hit or kicked by other children, and (5) is teased or made fun of by peers. This measure has high concurrent validity as reflected in significant correlations between victimization score and assessments of peer rejection, teacher-rated social problems, and parent-rated social problems (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002). The five items that composed the Teacher Report of Peer Victimization are internally consistent; for this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .80. Past research has found agreement between the Teacher Report of Victimization and victimization as assessed by self, peer, and parent reports (Ladd & Kochenderfer-Ladd, 2002).

Children’s Social Behavior Scale – Teacher Form (CSBS-T)

Sixth grade teachers also completed a modified version of the CSBS-T (Crick, 1996). The modified version of the CSBS-T was expanded to include an additional social aggression item (i.e., nonverbal social exclusion). Teachers rated whether socially and physically aggressive behaviors were characteristic of the target child using a 1–5 Likert scale (1 = never true of this child and 5 = almost always true of this child). Teachers’ reports of adolescents’ social behaviors on the CSBS-T are positively correlated with peer nominations (Crick, 1996). The social and physical aggression subscales are internally consistent; for this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .86 and .93, respectively.

Child Behavior Checklist-Teacher Report Form

We administered the Child Behavior Checklist-Teacher Report Form (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) to seventh grade teachers. Teachers rated how characteristic 118 problem items were of the child’s behavior over the past two month period using a 0–2 scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true). These items compose eight subscales: anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior. Of interest to the current study was the internalizing problems scale which is a composite of the anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints subscales. Psychometric properties were tested with a nationally representative sample of clinically referred and non-referred students; the scales are internally consistent with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .72 to .95 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. The descriptive statistics are from the sample data and are not those estimated within our FIML (full information maximum likelihood) analysis that accounts for missing data (see below). However, the results are quite similar so we report those from the sample.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| Mean (SD) |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attractiveness | 2.53 (.57) |

- | −.22** | −.09 | −.24** | −.16t |

| 2. Victimization | 1.18 (.31) |

- | .08 | .12 | .30** | |

| 3. Anxious Depression | 1.55 (2.72) |

- | .23** | .28** | ||

| 4. Withdrawn Depression | .96 (1.70) |

- | .24** | |||

| 5. Somatic Complaints | .32 (1.01) |

- |

p < .10

p<.05

p<.01

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine the importance of attractiveness as an antecendent of peer victimization in relation to other known predictors. Aggression is one of the established predictors of victimization (Hanish & Guerra, 2000), and we conducted analyses to examine the relative strength of the association between attractiveness and victimization in relation to aggression. In preliminary analyses, we tested whether the relationship between victimization and attractiveness was affected by the addition of the teacher reports of social and physical aggression. Parallel to our analysis of mediation, we used FIML to keep the largest possible sample. The results for attractiveness continued to be significant (standardized parameter estimate = −.23, p<.01) while the estimates for social and physical aggression variables were nonsignificant (standardized parameter estimate = .15 and .16, respectively, p>.1 in both cases).

Below we present the results of our analysis of mediation. We examined whether teacher-reported victimization mediated the relation between physical attractiveness and internalizing problems.

Analysis of Mediation

We followed the steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) in order to test for mediation and supplemented the statistical test conventionally used with a more robust test as described below (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The first step in demonstrating mediation is to determine that the initial variable (attractiveness) is correlated with the outcome variable (internalizing problems). The second step entails demonstrating that the initial variable (attractiveness) is correlated with the mediating variable (victimization). The third step requires demonstrating that the mediating variable (victimization) predicts the outcome variable (internalizing problems) even after controlling for the initial variable (attractiveness). The fourth step consists of demonstrating that the initial variable (attractiveness) is no longer a significant predictor of the outcome variable (internalizing problems) when the mediating variable (victimization) is also included in the same analysis. Partial mediation is established if the conditions outlined in the first three steps are achieved and full mediation is achieved in the event that the conditions outlined in all four steps are achieved.

Structural equation modeling is well-suited for testing for mediation using Baron and Kenny’s method (Hopwood, 2007). We used structural equation modeling to test our hypothesized model of the relationships between attractiveness, victimization, and internalizing problems. Analyses were conducted using AMOS 17.0 (Arbuckle, 2008) and supplemented with Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Throughout we had to account for missing data. To keep the largest possible sample we used direct full information maximum likelihood (FIML) that is appropriate under either the assumption of data missing completely at random or missing at random (Allison, 2003). Under these assumptions the results were unbiased and efficient. This procedure allows all observations that have data to contribute to the estimates without the well-known problems related to dropping observations or imputing data. The only restriction was that there had to be an attractiveness rating for each student.

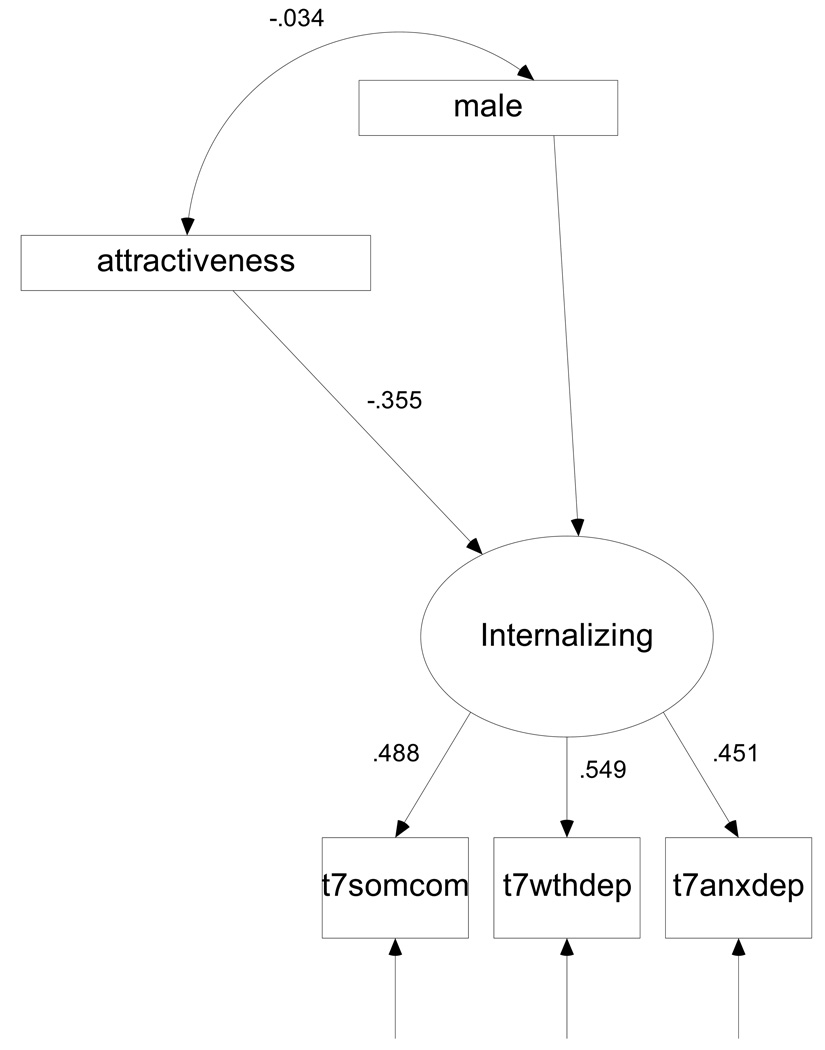

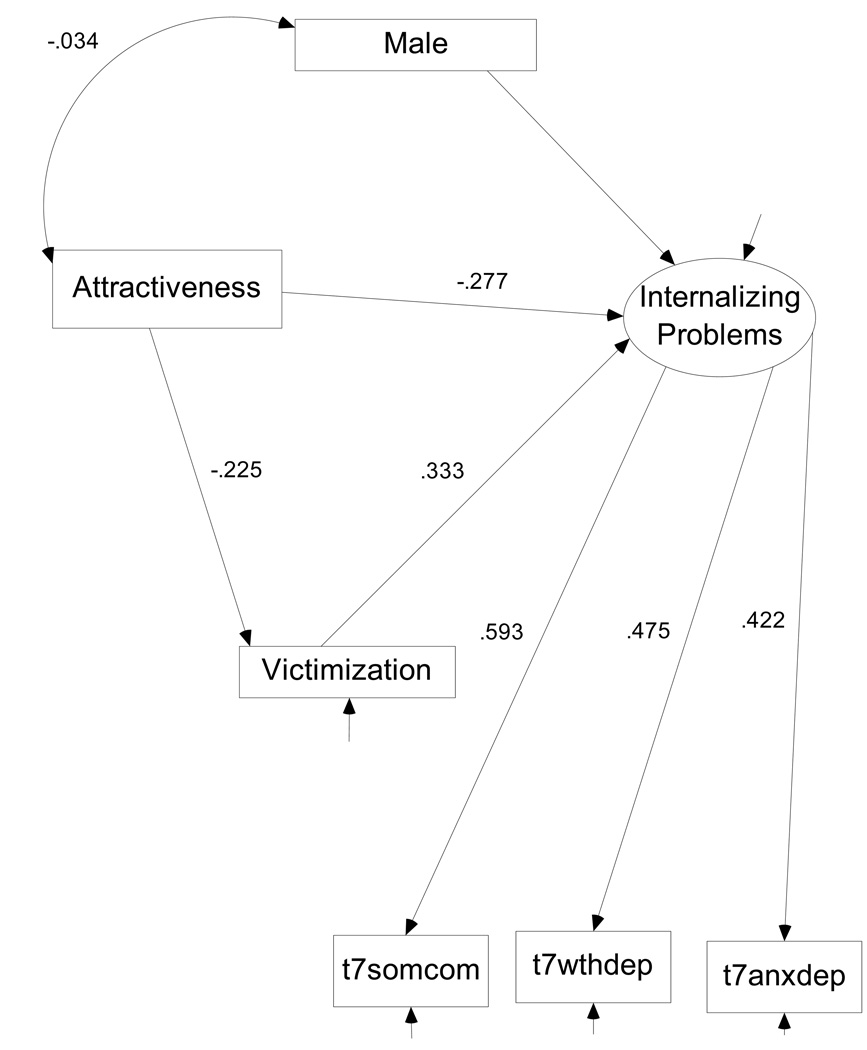

We used a two-phased modeling approach. In the first phase, we tested the simplified model (Figure 1) in which attractiveness predicts internalizing problems. We then tested the mediated model (Figure 2) in which victimization mediates the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problem. In both models, teacher-rated anxious depression, withdrawn depression, and somatic complaints as measured by the Child Behavior Checklist – Teacher Report Form were used to indicate the latent construct of internalizing problems. We included gender as a predictor of internalizing problems in the simplified and mediated models.

Figure 1. Simplified model.

Note: χ2 (4, N = 175) = 2.80, p = .59.

Figure 2. Mediated model.

Note: χ2 (7, N = 175) = 7.53, p = .38.

Simplified Model

In the simplified model, we tested whether attractiveness predicted internalizing problems. The results of this model with significant standardized parameter estimates are presented in Figure 1. The simplified model fit the data well (χ2 (4, N = 175) = 2.80, p = .59; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00, p(RMSEA≤0.05) < 0.76. Indicator loadings for the latent construct of internalizing problems were significant, ps < .01. Attractiveness was a significant negative predictor of internalizing problems (standardized parameter estimate = −.36, p < .01) which is consistent with the first step of Baron and Kenny’s (1986) framework. There were no significant effects for gender in the simplified model.

Mediated Model

We then examined an expanded model in which victimization mediated the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems. The results of the mediated model with significant standardized parameter estimates are presented in Figure 2. This model also fit the data well, χ2 (7, N = 175) = 7.53, p = .38; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .02, p(RMSEA≤0.05) < 0.65.

Steps two through four of the Baron and Kenny (1986) framework were assessed in this model. Attractiveness was a significant negative predictor of victimization (standardized parameter estimate = −.23, p < .01). Victimization was a significant positive predictor of internalizing problems (standardized parameter estimate = .33, p < .01). With victimization in the model, attractiveness was still a significant negative predictor of internalizing problems (standardized parameter estimate = −.28, p < .05). However, the parameter estimate of the path between attractiveness and internalizing problems decreased from -.36 in the previous model to -.28 in the current model which included victimization. This is a 22% reduction in the attractiveness-internalizing problems parameter estimate from the simplified model to the mediated model.

We adopted two approaches to statistically test for mediation. In the first, the standardized mediated (indirect) effect was tested within the structural equation model, the equivalent of a Sobel test, and found to be statistically significant (p<0.05). Thus, the model is consistent with partial mediation as assessed with the Baron and Kenny (1986) method. As was the case in the simplified model, there were no significant effects of gender in this model. Recent research, however, suggests that this approach suffers from low power in detection of the mediated effect and the type I error rate (MacKinnon et al., 2002). The primary reason for this is the construction of the standard error in the Baron and Kenny approach assumes the product is normal when there is evidence that the product is not normal. Our second approach accounts for this nonnormality. We construct, using MacKinnon’s PRODCLIN program, an asymmetric confidence interval that accounts for the nonnormal distribution of the product of normal random variables (MacKinnon et al., 2007). These results support the results found with the traditional approach as both the 95 percent and 99 percent confidence intervals are negative (CI.95 = −0.159, −0.015; CI.99 = −0.195, −0.003).

Discussion

Results provided support for our hypotheses regarding the relationships between attractiveness, victimization, and internalizing problems. As predicted, attractiveness was negatively related to victimization and internalizing problems. Further, experiences of peer victimization partially mediated the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems as had been expected. Less attractive adolescents in this study were more likely to be victimized by their peers. Peer victimization did not, however, fully account for the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems, which is to be expected given that unattractive adolescents may be treated more negatively by parents (e.g., Bergman, 2005; Elder et al., 1985), teachers (e.g., Kenealy et al., 1988), and other significant interaction partners (Langlois et al., 2000). Although the effects here were small though significant, this study suggests that facial attractiveness may be one of a constellation of factors that relates to peer victimization and maladjustment.

Low attractiveness was associated with disadvantageous treatment and outcomes, consistent with findings in previous studies. Past work has shown that less attractive children are at a social disadvantage (e.g., Dion, 1973; Langlois et al., 2000; Salvia et al., 1975; Vaughn & Langlois, 1983). This study was one of the first to find that these peer preferences translate into differential treatment. No known previous investigations have examined the relationship between independent measures of attractiveness and victimization. This study breaks new ground by demonstrating a negative relationship between an independent measure of attractiveness and peer victimization.

Previous research with children and adolescents has found positive correlations between victimization and maladjustment (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Prinstein et al., 2001). The current findings suggest that less attractive children are more likely victimized which in turn is associated with greater internalizing problems. That these negative peer experiences contributed to higher levels of internalizing disorders is consistent with the previously articulated hypothesis that appearance-based discrimination leads less attractive individuals to experience higher rates of maladjustment (Burns & Farina, 1992; Patzer & Burke, 1988) but is one of the first empirical tests of this theory.

As had been found in previous studies with clinical populations, attractiveness was negatively correlated with adjustment difficulties (e.g., Farina et al., 1977; Napoleon et al., 1980). Attractiveness and adjustment have rarely been studied in nonclinical populations. The current study is one of the first to find a relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems in a typically developing early adolescent sample. Less attractive adolescents were treated more negatively than their more attractive peers, and likely internalized some of these experiences of peer maltreatment as evidenced by greater internalizing problems.

An alternative explanation for these findings is that internalizing problems lead to a less attractive appearance. Many researchers claim that structural characteristics beyond the influence of routine grooming are necessary for a face to be attractive (e.g., Langlois & Roggman, 1990). However, modifiable aspects of facial variation could also contribute to attractiveness judgments. For instance, the use of cosmetics has been found to enhance attractiveness (Mulhern, Fieldman, Hussey, Leveque, & Pineau, 2003). Individuals who suffer from depression often exhibit poor grooming behavior (Johnson & Indvik, 1997) and this in turn may influence their appearance.

All results must be interpreted with consideration of the study’s methodological limitations. First, we relied on teacher ratings of victimization. Although previous research suggests that teachers may provide important information regarding their students’ peer relations (e.g., Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005), their knowledge of some adolescent experiences may be limited. Another shortcoming of the study is that we only began taking photographs in sixth grade, and appearance information collected from earlier developmental points would allow us to better evaluate whether the relationship between attractiveness and internalizing problems is bidirectional. The study was also limited by the exclusive focus on facial attractiveness. It is likely that other aspects of appearance, such as body size, contribute to peer experiences and in turn adjustment (e.g., Cramer & Steinwert, 1998; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1998). Further, it is important to recognize that appearance is just one of a host of factors that places children at risk for victimization. Behavioral factors that are predictors of victimization such as aggressiveness (Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Mahady Wilton et al., 2000) and submissiveness (Schwartz et al., 1993) may interact with attractiveness.

Despite these limitations, this study has important strengths. This is one of the first investigations to examine the effects of attractiveness on peer victimization and internalizing problems. Our methodology for obtaining attractiveness ratings was based on the most recent face processing research (Hoss, Ramsey, Griffin, & Langlois, 2005) and proved to be highly reliable. Although many researchers have hypothesized that attractiveness elicits differential treatment which in turn influences adjustment (e.g., Burns & Farina, 1992; Patzer & Burke, 1988), this is one of the first empirical tests of this proposition.

Future research is needed to better understand the nature of the relationships between physical attractiveness, differential peer treatment, and internalizing difficulties. Specifically, future studies should seek to identify factors that moderate the relationship between attractiveness and victimization. For instance, high social competence may help protect a less attractive child from experiencing victimization whereas low social competence may serve as a risk factor for victimization for even the most attractive child. Other potential moderators such as popularity and social status should also be examined. Future research should also simultaneously examine independent ratings of attractiveness and self-perceived appearance; victimization as a function of appearance would likely influence one’s self-concept and a negative image of one’s appearance may be a further risk factor for victimization. Longitudinal investigations may be especially informative because although attractiveness is fairly stable across the lifespan, some individuals differ markedly in their appearance at points in their lives (Zebrowitz, Olson, & Hoffman, 2003). Attractiveness may be especially likely to change following puberty, the second most rapid period of physical change surpassed only by infancy (Boxer, Tobin-Richards, & Petersen, 1983). Developmentally examining changes in victimization and psychosocial adjustment as a function of attractiveness can be likened to a natural experiment in which attractiveness is “varied” and the subsequent effects are noted (Langlois et al., 1995). Changes in attractiveness may be accompanied by changes in experiences of peer maltreatment and, in turn, psychosocial adjustment. Further, longitudinal investigations will afford the opportunity to examine whether peer responses to attractiveness change across development. Even though being attractive is usually a large advantage, there are cases when attractiveness can be a disadvantage; some studies have shown this for women in managerial positions (Heilman & Stopeck, 1985). Later in adolescence when romantic relationships and sexual activity become more frequent (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Furman & Wehner, 1997), adolescents who are extremely attractive may also become victimized by peers who are envious that attractive individuals have greater access to dating partners (Walster et al., 1966). Adolescents in dating relationships, especially females, may feel threatened by extremely attractive, same-sex peers (Dijkstra & Buunk, 2002).

In the current study, less attractive early adolescents experienced more victimization and internalizing difficulties than their more attractive counterparts. These findings hold important implications for designing interventions to reduce bullying and assist victimized youth. Because unattractive individuals are at greater risk for victimization and internalizing problems during middle school, teachers and other adults may be able to assist by paying close attention to students who are victimized as a function of their appearance. Additionally, interventions to reduce appearance-based victimization can be directly aimed at children and adolescents. Past research has shown some success for appearance-targeting educational programs, which have been found to reduce stereotyping regarding body size and discourage related teasing (Irving, 2000). However, it may be difficult for short-term interventions to have lasting influence because the beauty is good stereotype is evident in very young children (Dion, 1973) and stereotype congruent portrayals (e.g., beautiful Cinderella and the ugly, evil stepsisters) are prevalent in the media (Smith, McIntosh, Bazzini, 1999). Despite the difficulty in changing behavior, future research can better inform interventions to assist children and adolescents who are continuously victimized as a result of their appearance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01 MH63076, K02 MH073616, and R01 HD060995. We are deeply grateful for the participation of children and families in this study and for the cooperation of a local school system that wishes to go unnamed. We thank Joanna Gentsch, Ahrareh Rahdar, and Michelle Wharton for assistance with data collection.

Contributor Information

Lisa H. Rosen, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, The University of Texas at Dallas

Marion K. Underwood, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, The University of Texas at Dallas

Kurt J. Beron, School of Economic, Political & Policy Sciences, The University of Texas at Dallas

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos users’ guide, Version 17.0. Chicago: SPSS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Archer R, Cash TF. Physical attractiveness and maladjustment among psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1985;3:170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KS. Update on bullying at school: Science forgotten? Developmental Review. 2007;27:90–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B. Unlovely, unloved? Maclean’s. 2005;118:48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Betan EJ, Roberts MC, McCluskey-Fawcett K. Rates of participation for clinical child and pediatric psychology research: Issues in methodology. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer AM, Tobin-Richards M, Petersen AC. Puberty: Physical change and its significance in early adolescence. Theory into Practice. 1983;22:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brunstein Klomek A, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Bullying, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:40–49. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242237.84925.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns GL, Farina A. The role of physical attractiveness in adjustment. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1992;118:157–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Key statistics from the National Survey of Family Growth. 2010 Retrieved March 22, 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/abc_list_s.htm#sexualactivity.

- Cillessen AHN, Terry RA, Coie JD, Lochman JD. Accuracy of teacher evaluations of children’s sociometric status postions. Department of Psychology, University of Conneticut; 2002. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD. Toward a theory of peer rejection. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 365–401. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Cillessen AHN. Peer rejection: Origins and effects on children’s development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1993;2:89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley CH. Human nature and the social order. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WM, Pepler DJ. Identifying and targeting risk for involvement in bullying and victimization. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-In Review. 2003;48:577–582. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Steinwert T. Thin is good, fat is bad: How early does it begin? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1998;19:429–451. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:2317–2327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku H. Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:376–385. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Nelson DA. Toward a more complete understanding of peer maltreatment: Studies of relational victimization. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children's treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR. Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review. 2005;34:147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Buunk BP. Sex differences in the jealousy-evoking effect of rival characteristics. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;32:829–852. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra JK, Lindenberg SM, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Veenstra R. The relation between popularity and aggressive, destructive, and norm-breaking behaviors: Moderating effects of athletic abilities, physical attractiveness, and prosociality. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Dion KK. Young children’s stereotyping of facial attractiveness. Developmental Psychology. 1973;9:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dion KK, Berscheid E, Walster E. What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;24:285–290. doi: 10.1037/h0033731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder D. The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal relations among female adolescents. Sociology of Education. 1985;58:154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Van Nguyen T, Caspi A. Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Development. 1985;56:361–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina A, Burns GL, Austad C, Bugglin C, Fischer EH. The role of physical attractiveness in the readjustment of discharged psychiatric patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:139–143. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina A, Fischer EH, Sherman S, Smith WT, Groh T, Mermin P. Physical attractiveness and mental illness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1977;86:510–517. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.5.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner EA. Adolescent romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. In: Shulman S, Collins WA, editors. New directions for child development (No. 78). Romantic relationships in adolescence: Developmental perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorham S. Marking time in Door County. Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonficition. 2005;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin AM, Langlois JH. Stereotype directionality and attractiveness stereotyping: Is beauty good or is ugly bad? Social Cognition. 2006;24:187–206. doi: 10.1521/soco.2006.24.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamermesh DS, Biddle JE. Beauty and the labor market. The American Economic Review. 1994;84:1174–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. Predictors of peer victimization among urban youth. Social Development. 2000;9:521–543. [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. A longitudinal analysis of patterns of adjustment following peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:69–89. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrist AW, Bradley KD. “You can’t say you can’t play”: Intervening in the process of social exclusion in the kindergarten classroom. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2003;18:185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman ME, Stopeck MH. Being attractive, advantage or disadvantage? Performance-based evaluations and recommended personnel actions as a function of appearance, sex, and job type. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1985;35:202–215. [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Miller-Johnson S, Simon TR, Schoeny ME. Validity of teacher ratings in selecting influential aggressive adolescents for a targeted preventive intervention. Prevention Science. 2006;7:31–41. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Malone MJ, Perry DG. Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1032–1039. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ. Moderation and mediation in structural equation modeling: Applications for early intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention. 2007;29:262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hoss RA, Ramsey JL, Griffin AM, Langlois JH. The role of facial attractiveness and facial masculinity/femininity in sex classification of faces. Perception. 2005;34:1459–1474. doi: 10.1068/p5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving LM. Promoting size acceptance in elementary school children: The EDAP Puppet Program. Eating Disorders. 2000;8:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PR, Indvik J. Blue on blue: Depression in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 1997;12:359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman P, Chen X, Choy SP, Ruddy SA, Miller AK, Fleury JK, Chandler KA, Rand MR, Klaus P, Planty MG. Indicators of school crime and safety, 2000 (NCES 2001-017/NCJ-184176) Washington, D.C.: Departments of Education and Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kenealy P, Frude N, Shaw W. Influence of children’s physical attractiveness on teacher expectations. Journal of Social Psychology. 1988;128:373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Kenealy P, Gleeson K, Frude N, Shaw W. The importance of the individual in the ‘causal’ relationship between attractiveness and self-esteem. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 1991;1:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kleck RE, Richardson SA, Ronald C. Physical appearance cues and interpersonal attraction in children. Child Development. 1974;45:305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: Cause of consequence of school maladjustment? Child Development. 1996;67:1305–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd B, Wardrop JL. Chronicity and instability of children's peer victimization experiences as predictors of loneliness and social satisfaction trajectories. Child Development. 2001;72:134–151. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz M, Friedberg J, Andrews D. Physical attractiveness and popularity: The mediating role of self-perception. The Journal of Psychology. 1985;119:219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen K, Rasanen E, Henttonen I. Children involved in bullying: Psychological disturbance and the persistence of involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:74–96. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Downs AC. Peer relations as a function of physical attractiveness: The eye of the beholder or behavioral reality? Child Development. 1979;50:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M. Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:390–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Ritter JM, Casey RJ, Sawin DB. Infant attractiveness predicts maternal behaviors and attitudes. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Roggman LA. Attractive faces are only average. Psychological Science. 1990;1:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Roggman LA, Casey RJ, Ritter JM, Reiser-Danner LA, Jenkins VY. Infant preferences for attractive faces: Rudiments of a stereotype? Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Roggman LA, Rieser-Danner LA. Infants' differential social responses to attractive and unattractive faces. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Baillargeon RH, Vermunt JK, Wu H, Tremblay RE. Age differences in the prevalence of physical aggression among 5- 11-year-old Canadian boys and girls. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:26–37. doi: 10.1002/ab.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenaars LS, Dane AV, Marini ZA. Evolutionary perspective on indirect victimization in adolescence: The role of attractiveness, dating, and sexual behavior. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:404–415. doi: 10.1002/ab.20252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Delaney M, Hess LE, Jovanovic J, von Eye A. Early adolescent physical attractiveness and academic competence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1990;10:4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lerner JV. The effects of age, sex, and physical attractiveness on child-peer relations, academic performance, and elementary school adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1977;13:585–590. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Hess LE, Schwab J, Jovanovic J, Talwar R, Kucher JS. Physical attractiveness and psychosocial functioning among early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:300–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM. A behavioral approach to depression. In: Friedman RJ, Katz MM, editors. The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research. Washington, DC: V. H. Winston; 1974. pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahady Wilton M, Craig WM, Pepler DJ. Emotional regulation and display in classroom victims of bullying: Characteristic expressions of affect, coping styles and relevant contextual factors. Social Development. 2000;9:226–245. [Google Scholar]

- Merrell KW, Buchanan R, Tran OK. Relational aggression in children and adolescents: A review with implications for school settings. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43:345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, Leveque JL, Pineau P. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? International Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2003;25:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2003.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Fifth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285:2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoleon T, Chassin L, Young RD. A replication and extension of “Physical Attractiveness and Mental Illness.”. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1980;89:250–253. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.89.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Faibisch L. Perceived stigmatization among overweight African-American and Caucasian adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23:264–270. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, Juvonen J. Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development. 2005;76:435–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, Juvonen J, Witkow M. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:37–48. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noles SW, Cash TF, Winstead BA. Body image, physical attractiveness, and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:88–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying or peer abuse at school: Facts and interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette JA, Underwood MK. Gender differences in young adolescents' experiences of peer victimization: Social and physical aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:242–266. [Google Scholar]

- Patzer GL, Burke DM. Physical attractiveness and child development. In: Lahey B, Kazdin AE, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 325–368. [Google Scholar]

- Perry DG, Kusel SJ, Perry LC. Victims of peer aggression. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Grimes CL, Foster KJ, Kupersmidt JB, Coie JD, Dearing K. Overt and relational aggression and victimization: Multiple perspectives within the school setting. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:523–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey JL, Langlois JH. Effects of the "beauty is good" stereotype on children's information processing. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2002;81:320–340. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2002.2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K, Slee PT. Bullying among Australian school children: Reported behavior and attitudes toward victims. Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;131:615–627. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1991.9924646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter JM, Casey RJ, Langlois JH. Adults' responses to infants varying in appearance of age and attractiveness. Child Development. 1991;62:68–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LH, Underwood MK. Attractiveness as a moderator of the association between aggression and popularity. The Journal of School Psychology. 2010;48:313–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DA, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. The relationship between memories for childhood teasing and anxiety and depression in adulthood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:149–164. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte RHJ, Engels RCME, Overbeek G, de Kemp RAT, Haselager GJT. Stability in bullying and victimization and its association with social adjustment in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9074-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Coie JD. The emergence of chronic peer victimization in boys’ play groups. Child Development. 1993;64:1755–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Nakamoto J, Toblin RL. Victimization in the peer group and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:425–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sifers SK, Puddy RW, Warren JS, Roberts MC. Reporting of demographics, methodology, and ethical procedures in journals in pediatric and child psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:19–25. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GJ. Facial and full-length ratings of attractiveness related to the social interactions of young children. Sex Roles. 1985:287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, McIntosh WD, Bazzini DG. Are the beautiful good in Hollywood? An Investigation of the beauty-and-goodness stereotype on film. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;21:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Talamelli L, Cowie H, Naylor P, Chauhan P. Profiles of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims and new victims of school bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2004;74:565–581. doi: 10.1348/0007099042376427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan CW, Langlois JH. Baby beautiful: Adult attributions of infant competence as a function of infant attractiveness. Child Development. 1984;55:576–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Brassard MR, Masia-Warner CL. The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescence. Child Study Journal. 2003;33:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Masia-Warner C. The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TN, Farrell AD, Kliewer W. Peer victimization in early adolescence: Association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:119–137. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606007X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Hughes M. The impact of physical attractiveness on achievement and psychological well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1987;50:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Langlois JH. Physical attractiveness as a correlate of peer status and social competence in preschool children. Developmental Psychology. 1983;19:561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Walster E, Aronson V, Abrahams D, Rottman L. Importance of physical attractiveness in dating behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;4:508–516. doi: 10.1037/h0021188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung K, Martin JL. The looking glass self: An empirical test and elaboration. Social Forces. 2003;81:843–879. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz LA, Olson K, Hoffman K. Stability of babyfaceness and attractiveness across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:453–466. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]