Abstract

Background

A considerable body of literature in the management sciences has defined leadership and how leadership skills can be attained. There is considerably less literature about leadership within medical settings. Physicians-in-training are frequently placed in leadership positions ranging from running a clinical team or overseeing a resuscitation effort. However, physicians-in-training rarely receive such training. The objective of this study was to discover characteristics associated with effective physician leadership at an academic medical center for future development of such training.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with medical professionals (attending physicians, residents, and nurses) at an academic medical center. The focus group discussion script was designed to elicit participants' perceptions of qualities necessary for physician leadership. The lead question asked participants to imagine a scenario in which they either acted as or observed a physician leader. Two independent reviewers reviewed transcripts to identify key domains of physician leadership.

Results

Although the context was not specified, the focus group participants discussed leadership in the context of a clinical team. They identified 4 important themes: management of the team, establishing a vision, communication, and personal attributes.

Conclusions

Physician leadership exists in clinical settings. This study highlights the elements essential to that leadership. Understanding the physician attributes and behaviors that result in effective leadership and teamwork can lay the groundwork for more formal leadership education for physicians-in-training.

Background

Leadership in medicine is characterized largely by what is not known. There are intuitions that good leadership advances health care, but many cannot define the essential aspects and attributes of leadership other than claim that they know it when they see it.1,2 Others recognize that leadership grows with experience, but wonder whether it can be taught or learned.1 In contrast, a considerable literature exists in management sciences that examines definitions of leadership and how leadership skills can be attained.3 Much of the work is based on competing theories. For example, both the “great man” and “trait leadership” theories focus on certain attributes or characteristics that lead to effective leadership.4 Other theories address variables within the environment or certain circumstances that suggest there is not one effective leadership style but that successful leaders adapt to their surroundings.5,6

Many leadership training programs are built upon the latter theories by focusing on individuals learning how to lead (behavioral leadership theory).5 Such training incorporates team building and highlights the need to take the input of other team members into account (participative theory).5 Other relevant frameworks include training on motivating team members to accomplish a task.6 No single synthesis can do justice to this vast literature, but commonly described characteristics of great leaders include vision, communication, integrity, single-mindedness, and other often abstractly defined concepts including charisma, wisdom, or inspiration.

The relevance of these elements to leadership is difficult to dispute in concept, but their application in medical practice is unclear. The literature on leadership in medical settings is considerably smaller. Some studies7,8 have looked at physician executives; a few,9 at surgical leadership. Researchers agree that physician leadership largely is understudied.10

Formal training in physician leadership has been shown to improve processes1,11 and outcomes12,13 in health care. Physicians-in-training are frequently placed in leadership positions ranging from running a clinical team to overseeing a resuscitation effort. However, they rarely receive general leadership training. Training that is provided focuses predominately on the skills to succeed during specific high-stress events.14–116 The lack of formal training in leadership has left physicians feeling unprepared not only for specific events17,18 but also unprepared for other, less well-defined leadership roles. Understanding physician attributes and behaviors that result in effective leadership can lay the groundwork for more formal leadership education for physicians-in-training. The first step in designing leadership training as part of graduate medical education should compare leadership qualities relevant for clinicians to current models of leadership in other fields.

The objective of this study was to discover characteristics associated with effective physician leadership to confirm whether models from other professional fields apply to medicine.

Methods

We conducted focus groups with medical professionals including attending physicians, residents, and nurses to learn what characterizes effective physician leadership and identify central elements of physician leadership. Participants came from a single institution and were recruited via e-mail. We completed 5 focus groups: 2 with internal medicine residents; and 1 each with attending physicians from general internal medicine and pulmonary/critical care, and critical care nurses. Each focus group lasted 1 hour and was moderated by 1 of the principal investigators after completing training by an experienced focus group moderator. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study.

We designed the focus group discussion script to elicit participants' perceptions of qualities necessary for physician leadership. The framework was developed by reviewing the literature on current leadership models3,4,7,9,19–21 and in discussions with leadership experts from management. We used guide questions to elicit responses and further probes to enhance discussion. The lead question asked participants to imagine a scenario in which they either acted as or observed a physician leader. Relevant probes asked them to think about what characteristics made or did not make them a good leader. Other key questions were: “What are the 5 biggest or most important characteristics of a physician leader?” and “What situations can you think of where physicians have to act as leaders?”

We recorded and transcribed each session. Two independent reviewers reviewed transcripts and analyzed the text content to identify the key domains of physician leadership. The analysis began with the framework of physician leadership, based on the literature review and discussions with experts in the field. Using NVivo 8 (QSR, Melbourne, Australia), the first reviewer added codes to the framework after review of transcripts. The codes were critically assessed by the entire research team before training a second reviewer who was not involved in creating the coding framework. The second reviewer then independently coded each transcript. The 2 reviewers met to resolve any differences. The final coding was reviewed by the entire team and collapsed into broader themes of physician leadership. The validity of the analysis was examined by member checking and by comparing the themes to leadership models in other industries.

Results

Seven residents, 6 interns, 6 attending physicians, and 5 nurses participated in the study. Nine of the participants (37.5%) were women. The coding agreement between the 2 reviewers was good, with a κ for the 34 coded themes ranging from 0.50 to 1.00 and a median κ of 0.84.

Although we did not give specific guidance about the context of the discussion, most participants discussed leadership in the context of a clinical team conducting teaching or patient care rounds. The team encompassed medical students, interns, and residents who were supervised by an attending physician or, occasionally, by a fellow who in turn was supervised by an attending physician. Rounds often incorporated nonphysician team members including nurses, respiratory therapists, and pharmacists. With further probing, participants revealed other situations in which physicians act as leaders, including overseeing a resuscitation, departmental administration, facilitating family meetings, acting as policy makers, running research laboratories, and managing private practices.

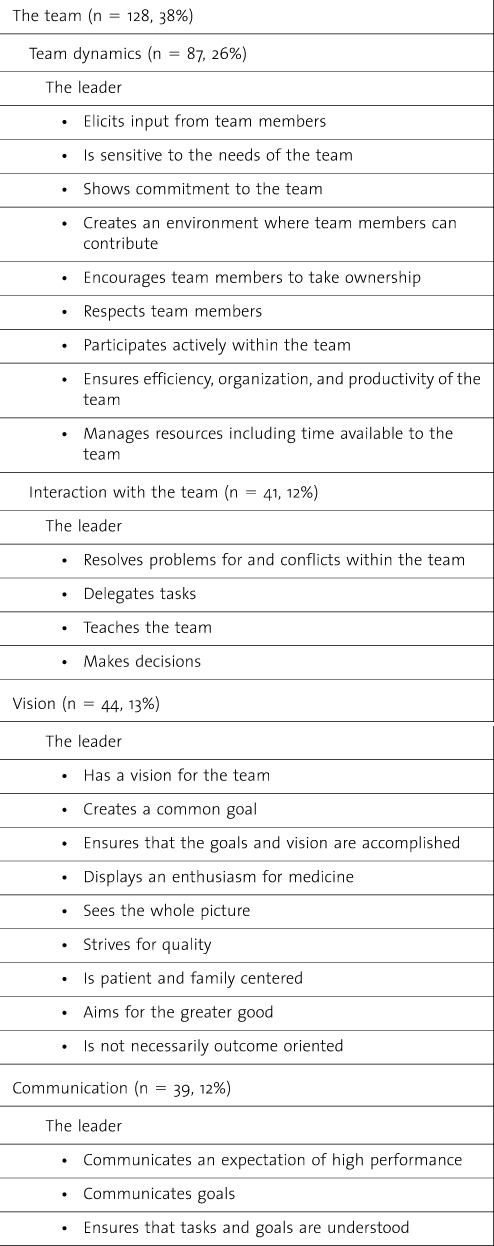

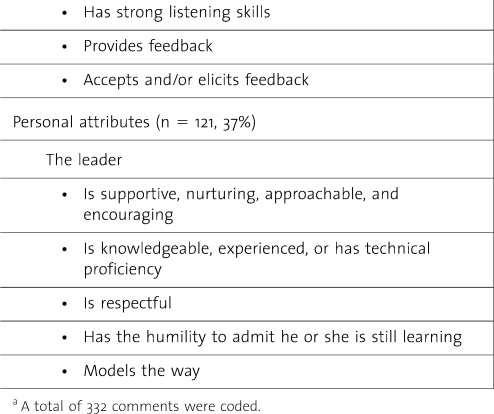

Content analysis yielded 4 predominant themes: team, vision, communication, and personal attributes of the leader (table).

table .

Characteristics of a High-Quality Clinical Physician Leadera

table .

Continued

The Team

The most common theme mentioned was the physician leader's ability to manage the medical team.

They use their team … you have a team filled with really intelligent people and you're going to utilize them in making the decisions … you're drawing on the group.

When discussing this aspect of leadership, the participants distinguished between the dynamics of the team and leader's interaction with his or her team.

Team Dynamics

Medical teams are often randomly assigned, with the actual make-up of the teams changing frequently. The participants of all focus groups believed that an effective physician leader should draw on the skills of these rapidly changing teams and ensure that they run smoothly.

Thinking of the team. It's what they do to the team dynamics as a whole…. Some teams just work incredibly well and some teams [don't] … there is something you can do to create a sort of really good team.

Participants described that a good team leader creates an environment that makes team members feel comfortable and enjoy their work. They felt that such an environment could be created while focusing on patient care and accomplishing the tasks at hand.

… it doesn't necessarily mean sort of like, the obvious like, “let's go bowling together.” It's not that, it's more just the way rounds are run to have those moments where everyone's laughing and sort of just relax for a bit and then really focus on doing a great job …

A concept had previously been described in high-action teams—hierarchical and dynamic leadership in trauma teams—where roles were dynamically delegated as the patient's condition or team composition shifted.22 To accomplish this, physician leaders should draw on the abilities and elicit input of their individual team members by creating an environment where team members feel comfortable enough to contribute their thoughts and ideas. These elements reflect more general views of participative leadership theory, which suggests that the ideal style is one that takes the input of others into account.23 Although the participants believed that the team leader should participate actively within the team, he or she is not simply another member. The leader takes on a managerial role. If managed effectively, the individual team members take ownership, draw from one another, and work together. The team as a whole, as well as each individual member, strives to accomplish the tasks.

You have high expectations and you're demanding in that regard. It's more that you know that people, trust that people, are capable. You're demonstrating that you believe that your team members are capable of something and you want them to achieve their potential.

Attending physicians explained the need to have high expectations, as a responsibility to the physicians-in-training under their supervision:

… we do have to have high expectations of them because they're the future doctors … at least they're getting formal structured evaluation, but when they're an attending they're not going to get that kind of evaluation, anymore.

Both residents and attending physicians felt that having a demanding attending physician would result in better performance by inspiring the supervisee to “live up to someone's expectations.” At the same time, comments suggested that not every demanding supervisor helps a trainee reach his or her potential. It can also be interpreted as mistreatment. A participant of 1 focus group explained that the underlying goal must be for team members to “achieve their potential.” In that way, the supervisee “feels they're getting something in return,” such as “they maybe learn more, they maybe feel like they're getting better by being pushed to their limits.”

The leader manages the available resources of the team as well. The participants believed that the 2 most important resources in the medical setting were time and skills of the people on the team. By being organized and efficient, the leader ensures that each team member is continuously engaged and challenged. Respondents noted that promoting team members' participation and engagement is a particularly challenging part of physician leadership for 2 reasons. First, medical teams typically comprise professionals at different stages of their training. Engaging the team on everyone's level was identified as important but difficult. Using the members to teach and supervise one another is one way to actively engage while teaching at a lower level. Second, leading a clinical team must balance patient care and teaching in a limited time period. With the introduction of resident work-hour limitations, even the most effective leaders may struggle to fit in both of these roles successfully. While this was not identified as an important issue by interns and residents, attending physicians expressed their struggle to find the balance. Attending physicians stated that, in order to make teaching rounds effective and still allow for more time to teach, they prepared ahead of time.

Interaction With the Team

Another important aspect of managing the team is the leader's interaction with and within the team. The most frequently mentioned concept to ensure that the team is managed effectively—and a main theme throughout the management and leadership literature—was task delegation. This is to ensure that the team's goals are accomplished.

Everyone knows what they are doing so everyone has a role and they feel like they are participating in a useful way.

The physician leader also interacts with the team by teaching. Most physician participants thought this was an especially important aspect of physician leadership in an academic setting or any setting with trainees: teaching not only to provide good patient care but to prepare future physicians who will continue to focus on education.

… by not teaching that intern why it wasn't or why it didn't have to be a concern right then. To me it showed a lack of concern, a lack of importance for the development of the next generation, and just setting a poor example that this intern twenty, thirty years down the road might try to follow himself.

Other roles included supervising team members and resolving any conflicts or problems that arise within the team.

Vision

All 5 focus groups discussed the importance of having vision and communicating it to the team. For example, since the care plan may change frequently during a single day of caring for a patient, this ensures that the team can continue to function. Similar leadership attributes have been termed “commander's intent” in the military, which outlines the basic purpose of any given operation.24 Participants also felt that such a vision is inspiring, invigorating and brings back the enthusiasm for medicine. Residents especially felt that a high-quality leader would renew their love for medicine that initially drew them to the field.

A good leader will really inspire you to push yourself a bit further and sort of really wake you up … all of us went into medicine because we must have had some enthusiasm for it even though at moments you think, “Why did I do this?” but then the really … good leaders remind you and sort of create that excitement again.

Creating enthusiasm was accomplished in several different ways including creating a safe environment that allowed people to enjoy themselves while still working hard. A large component, however, was role modeling, such as role modeling an attending physician's own satisfaction with his or her job and making the important realization that students, interns, and residents are in their formative medical years.

Communication

Similar to previous literature on leadership and team effectiveness,24 communication skills were seen as essential to other leadership elements: to communicate the vision to the team and to build a healthy team dynamic and strong team interaction. The leader strives for continuous improvement by providing and accepting feedback. In a similar manner, the leader is able to identify and address problems, conflicts, and dissent that interfere with the team's goal.

When they go on rounds making sure that everybody on the team [is] on the same page with the plan … just so everyone knows what the plan is for that day, what needs to happen.

By discussing the details of the care, interns and residents felt they were able to make a decision when results were received, without reconvening the team, since they understood the bigger picture. In addition, discussing details and explaining why they are important not only helped with patient care in this way but also creates an environment where:

… everyone's opinion is valued and everyone feels it's an open environment that their opinion, no matter what level of training they're at, is encouraged and accepted.

Personal Attributes of the Leader

Most participants mentioned attributes relating to the leader as a person. These elements fall into both trait theory of leadership—traits the leader is born with—and behavioral theory—traits that a leader can learn. Some of these were a general statement about the leader's personality, such as a difficult to describe “leadership quality,” whereas some participants were more specific. Specific comments included being supportive, approachable, and encouraging. The nurse participants particularly stressed the need for a physician leader to be respectful to other team members, the patient, and the patient's family.

Each focus group also mentioned that the leader's abilities related to the task at hand were necessary for success. The physician had to be credible to the members of the team by exhibiting knowledge, experience, or technical proficiency. However, participants stated that leaders could ask for help without jeopardizing their credibility. In fact, the leader was even more respected if he or she had the humility to recognize that other members have different areas of expertise and admit that he or she is willing and able to learn from others.

Discussion

From our focus groups, we identified 4 themes important to physician leadership: management of the team, establishing a vision, communication, and personal attributes. Although we did not give specific guidance about the context of the discussion, most participants discussed leadership in the context of a clinical team. Participants described everyday leadership that is needed for taking care of patients, while teaching interns and residents, in a team composed of interns, residents, fellows, and attending physicians. In contrast, prior studies of physician leadership have focused on the characteristics of physicians in an executive or organizational role. This reflects a more narrow view of physician leadership.7,10,20,21 In contrast, focus group discussions centered on physician leadership in clinical settings. Many leadership attributes we identified are similar to those identified in physician executives. For example, communicating a clear plan and vision for the team (eg, by illustrating the care plan for a patient and explaining why each test was necessary) is a common theme in leadership models.

There are several key differences. Most types of leaders inspire a shared vision. An executive is often credited with vision when balancing the organization's future with its present. In clinical leadership, however, vision is often about the moment—sometimes embodied by the patient at hand. But our informants did reflect that the best leaders conveyed an enthusiasm for medicine and its future by role modeling one's own satisfaction and creating a pleasant work environment. Interviews about leadership among physician executives sometimes emphasize the importance of challenges to the current system.20 These themes did not arise in our more clinical setting.

Our focus groups were performed within a single department at 1 academic institution. This limits the generalizability of the findings. We also focused on leadership in general and did not attempt to elicit differences between practicing physicians and those in training, nor did we ask questions regarding the merits of leadership training.

Conclusion

Focus group participants centered on physician leadership in clinical settings and this research highlights the elements essential to that leadership. Although prior studies of physician leadership have focused mainly on the characteristics of physicians in an executive or organizational role, the focus group participants discussed leadership in the context of a clinical team. They identified 4 themes important to physician leadership: management of the team, establishing a vision, communication, and personal attributes. While we do not know how well any of these attributes can be taught or learned, understanding clinical physician leadership is the first step before attempting to improve it. For example, for organizations that wish to increase physician participation in shaping their future, understanding how a physician leads a medical team may help to shape future leadership training. Understanding the way a physician leads clinical teams may also be important in optimizing the team's function.

In academic institutions, clinical teams form and dissolve fairly rapidly and memberships are often selected by chance. A physician leader must be able to quickly adapt to new situations and new team members who may not have worked together before. The focus group participants highlighted the leader characteristics that would allow for robust team dynamics, despite this fluid team construction, and could be highlighted in formal training. Many of these characteristics are found in other leadership models that could be modified to equip clinicians with leadership training.

Knowledge of the characteristics of effective clinical physician leadership also has implications for medical education. Many experts have proposed more formal leadership education for physicians-in-training, whether or not they anticipate a future leadership role.20,21,25 Future work should examine if formal training improves the function and productivity of medical teams and patient outcomes, as well as whether teams would more easily deal with stressors.

Footnotes

All authors are at University of Pennsylvania. C. Jessica Dine, MD, MSHPR, is assistant professor at the Department of Medicine; Jeremy M. Kahn, MD, MS, is assistant professor at the Department of Medicine and the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics; Benjamin S. Abella, MD, is at the Department of Emergency Medicine; David A. Asch, MD, is professor of Medicine at the Department of Medicine and director of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics; and Judy A. Shea, PhD, is professor of Medicine at the Department of Medicine.

References

- 1.Stoller JK, Rose M, Lee R, et al. Teambuilding and leadership training in an internal medicine residency training program. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAlearney AS. Leadership development in healthcare: a qualitative study. J Organ Behav. 2006;27(7):967–982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horner M. Leadership theory: past, present and future. Team Performance Management. 1997;3(4):270–287. [Google Scholar]

- 4.House RJ, Howell JM. Personality and charismatic leadership. Leadership Q. 1992;3(2):81–108. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bass R. The Bass Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications. New York, NY: Free Press; 2008. Directive versus participative leadership; pp. 458–497. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe KB, Kroeck KG, Sivasubramaniam N. Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic review of the mlq literature. Leadership Q. 1996;7(3):385–425. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons MF, Ford D, Singer GR. Physician leadership: how do physician executives view themselves? Physician Exec. 1996;22(9):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuckerman HS, Hilberman DW, Andersen RM, et al. Physicians and organizations: strange bedfellows or a marriage made in heaven? Front Health Serv Manage. 1998;14(3):3–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz IB, Horwitz SK, Daram P, et al. Transformational, transactional, and passive-avoidant leadership characteristics of a surgical resident cohort: analysis using the multifactor leadership questionnaire and implications for improving surgical education curriculums. J Surg Res. 2008;148(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthrie MB. Challenges in developing physician leadership and management. Front Health Serv Manage. 1999;15(4):3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morey JC, Simon R, Jay GD, et al. Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1553–1581. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea-Lewis A. Teamwork: crew resource management in a community hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31(5):14–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2009.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells R, Jinnett K, Alexander J, et al. Team leadership and patient outcomes in US psychiatric treatment settings. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(8):1840–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels K, Lipman S, Harney K, et al. Use of simulation based team training for obstetric crises in resident education. Simul Healthc. 2008;3(3):154–160. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31818187d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunziker S, Tschan F, Semmer NK, et al. Hands-on time during cardiopulmonary resuscitation is affected by the process of teambuilding: a prospective randomised simulator-based trial. BMC Emerg Med. 2009;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pliego J. F, Wehbe-Janek H, Rajab MH, et al. OB/GYN boot cAMP using high-fidelity human simulators: enhancing residents' perceived competency, confidence in taking a leadership role, and stress hardiness. Simul Healthc. 2008;3(2):82–89. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181658188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes CW, Rhee A, Detsky ME, et al. Residents feel unprepared and unsupervised as leaders of cardiac arrest teams in teaching hospitals: a survey of internal medicine residents. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(7):1668–1672. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000268059.42429.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Schaik SM, Von Kohorn I, O'Sullivan P. Pediatric resident confidence in resuscitation skills relates to mock code experience. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008;47(8):777–783. doi: 10.1177/0009922808316992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein K, Ziegert J, Knight A, et al. Shared, hierarchical, and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Adm Sci Q. 2006;51(4):590–621. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusy M, Essex LN, Marr TJ. No longer a solo practice: how physician leaders lead. Physician Exec. 1995;21(12):11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xirasagar S, Samuels ME, Stoskopf CH. Physician leadership styles and effectiveness: an empirical study. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(6):720–740. doi: 10.1177/1077558705281063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein K, Ziegert J, Knight A, et al. Shared, hierarchical, and deindividualized leadership in extreme action teams. Adm Sci Q. 2006;51(4):590–621. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaeffer LD. The leadership journey. Harv Bus Rev. 2002;80(10):42–47,127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crighton M. Improving team effectiveness using tactical decision games. Safety Sci. 2009;47(3):330–336. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farley H, Casaletto J, Ankel F, et al. An assessment of the faculty development needs of junior clinical faculty in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(7):664–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]