Abstract

We have recently discovered that the insulin-like growth factor receptor I (IGF-IR) is up-regulated in human invasive bladder cancer and promotes migration and invasion of transformed urothelial cells. The proteoglycan decorin, a key component of the tumor stroma, can positively regulate the IGF-IR system in normal cells. However, there are no available data on the role of decorin in modulating IGF-IR activity in transformed cells or in tumor models. Here we show that the expression of decorin inversely correlated with IGF-IR expression in low and high grade bladder cancers (n = 20 each). Decorin bound with high affinity IGF-IR and IGF-I at distinct sites and negatively regulated IGF-IR activity in urothelial cancer cells. Nanomolar concentrations of decorin promoted down-regulation of IRS-1, one of the critical proteins of the IGF-IR pathway, and attenuated IGF-I-dependent activation of Akt and MAPK. This led to decorin-evoked inhibition of migration and invasion upon IGF-I stimulation. Notably, decorin did not cause down-regulation of the IGF-IR in bladder, breast, and squamous carcinoma cells. This indicates that decorin action on the IGF-IR differs from its known activity on other receptor tyrosine kinases such as the EGF receptor and Met. Our results provide a novel mechanism for decorin in negatively modulating both IGF-I and its receptor. Thus, decorin loss may contribute to increased IGF-IR activity in the progression of bladder cancer and perhaps other forms of cancer where IGF-IR plays a role.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Growth Factors, Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF), Signal Transduction, Transformation, Bladder Cancer, Decorin Proteoglycan, IGF-IR, Migration and Invasion, Signaling

Introduction

Bladder cancer is one of the most common cancers in the United States with 70,530 estimated cases and 14,680 estimated deaths in 2010 (1). Regardless of treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy, bladder cancers often recur and metastasize to distant sites. The prognosis for low grade tumors is generally good, but ∼10–15% of these patients later develop invasive disease. Prognosis of high grade tumors is instead much less favorable, with only 50% survival at 5 years (2, 3). Invasive tumors frequently progress to life-threatening metastasis, which is associated with a 5-year survival rate of 6% (2). Thus, understanding the mechanisms that regulate bladder tumor invasion and metastasis is crucial to both outcome prediction and improvement of treatment for this devastating disease.

The insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF-IR)4 is essential for cell growth in vitro (4, 5) and in vivo (6–8). Mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the Igf1r gene exhibit severe growth retardation and die shortly after birth because of respiratory failure (9–11). IGF-IR plays also an essential role in transformation, as suggested by experiments performed on fibroblasts derived from Igf1r−/− mice. These cells were refractory to transformation induced by several tumorigenic agents (viral oncogenes, including Ras, SV40 large T Ag and overexpressed epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors, and various chemical agents) but were transformed when the Igf1r was re-expressed (7). Further experimental and epidemiological studies have confirmed that activation of IGF-IR is involved in the development of many common neoplastic diseases, including carcinomas of the lungs, prostate, pancreas, liver, colon, and breast (12). The transforming potential of the IGF-IR likely depends on its ability to protect from apoptosis (13) and to induce cell motility (14, 15). In some experimental models, increased cell migration mediated by the activation of the IGF-IR has been directly linked to tumor progression (16) and to an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (17). Consequently, the IGF-IR has become a very attractive target for cancer therapy, and in fact antibodies against the IGF-IR are currently in Phase I clinical trials (18).

We have recently discovered that the IGF-IR is overexpressed in invasive bladder cancer, where it functions as a “scatter factor” and promotes motility and invasion without affecting cell proliferation (19). These effects require the activation of Akt and MAPK pathways, and the binding of IGF-I to IGF-IR induces Akt- and MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of paxillin, which is necessary for promoting motility (19). Thus, the IGF-IR may play a critical role in promoting the transition to an invasive and possibly metastatic stage of bladder cancer (19).

Decorin, the prototype member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans, affects the biology of various types of cancer by physically down-regulating several receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) involved in growth and survival (20–23). Decorin directly binds to EGFR and Met and down-regulates their activity (24–29).

The first evidence linking decorin to cancer came from a study utilizing Dcn/p53 double knock-out mice (30). Mice that lack p53 develop a spectrum of sarcomas, lymphomas, and, less frequently, adenocarcinomas. Remarkably, mice lacking both the Dcn and p53 genes show a faster rate of tumor development and succumb almost uniformly to a very aggressive form of thymic lymphomas within 6 months. The second line of evidence arose from the analysis of the Dcn-null mice. Approximately 30% of these mice develop spontaneous intestinal tumors (31).

An antioncogenic role for decorin has been documented in various experimental settings including breast (26) and ovarian (32) carcinoma cells, syngeneic rat gliomas (33), and squamous and colon carcinoma xenografts (34–36). A possible mechanism of action occurs via a transient activation of the EGFR (24, 37), followed by down-regulation of the receptor itself (27, 38), which leads to growth suppression. Adenovirus-mediated or systemic delivery of decorin prevents metastases in various breast tumor models (39–42). Moreover, systemic delivery of decorin retards the growth of prostate cancer in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis where the tumor suppressor PTEN gene was conditionally deleted in the prostate (43).

In two experimental animal models of inflammatory angiogenesis in the cornea (44) and unilateral ureteral obstruction (45, 46), decorin-deficient mice (47) show a significant increase in IGF-IR levels, suggesting that decorin may regulate the IGF-IR in vivo. However, all of these studies were performed with “normal” cells, and therefore there are no published data on the role of decorin in modulating cancer growth via the IGF-IR in transformed cells or in tumor models.

Here, we show that the IGF-IR is markedly up-regulated in high grade compared with low grade bladder cancer tissues. In contrast, decorin expression is lost in bladder tumor tissues, suggesting that decorin loss may modulate IGF-IR activity. We further demonstrate that decorin binds with high affinity for both the IGF-IR and IGF-I at distinct sites and represses IGF-IR activity in urothelial cancer cells. In addition, decorin inhibits IGF-I-dependent activation of downstream effectors proteins, thereby counteracting cancer cell migration and invasion. Thus, decorin may work as a natural IGF-IR antagonist contributing to IGF-IR-dependent progression in bladder cancer and perhaps other types of tumors where IGF-IR plays a role.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Materials

Urothelial carcinoma-derived human 5637 and T24 cells, as well as MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells and HeLa squamous carcinoma cells, were obtained from ATCC. 5637 and T24 cells were maintained in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS. MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Serum-free medium (SFM) is DMEM supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 50 μg/ml of transferrin (Sigma-Aldrich). Human recombinant decorin proteoglycan and protein core were produced as described before (48). Briefly, decorin-expressing 293-EBNA cells were created by transferring the vaccinia decorin construct into the pCEP4 (Invitrogen) expression vector. Following transfection, stable expressing cells were selected with hygromycin. The cells were then grown to saturation in the Celligen Plus bioreactor and protein production achieved by switching to serum-free culture medium. Conditioned medium was collected every 48 h. Following concentration of the conditioned medium using a Pellicon 2 tangential flow system (Millipore, Bedford, MA), recombinant decorin was purified as described above. Both expression systems resulted in the production of protein cores and proteoglycan forms of decorin. In some experiments, the protein core was separated from proteoglycan following anion exchange chromatography on Q-Sepharose and elution with a linear gradient of 0.15–2 m NaCl in PBS, 0.2% CHAPS. Protein core samples were analyzed by gel filtration chromatography before and after dialysis against water and freeze-drying. Dried proteins were resuspended in TBS (20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.0) and chromatographed on Superose 6 HR 10/30 (Amersham Biosciences) in TBS with or without 2.5 m GdnHCl.

Human recombinant IGF-IR was purchased from R & D Systems (305-GR) and consisted of a ∼104-kDa single chain polypeptide with a ∼81-kDa α subunit (containing the ligand-binding domain of the receptor) and a 23-kDa β subunit of the IGF-IR.

Immunohistochemical Analysis of IGF-IR and Decorin Expression in Bladder Cancer Tissues

Immunohistochemical analysis of IGF-IR levels in bladder tissues was performed as previously described (19, 49). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections from 20 high grade and 20 low grade urothelial cell carcinomas and adjacent normal tissues were obtained from the Pathology Tissue Bank of Thomas Jefferson University. Informed consent to use excess pathological specimens for research purposes was obtained from all patients. The slides were incubated with 1:500 dilution of an anti-human IGF-IR antibody (clone G11; Ventana Medical System) as described (19). Decorin expression was detected using a rabbit affinity-purified anti-decorin antibody that recognizes the first 17 amino acids of the decorin protein core as described before (28). IGF-IR samples were dichotomized into IGF-IR low (<30% cancer cell positivity) or IGF-IR high (>30% cancer cell positivity). For decorin, samples were dichotomized as negative (0) or weak (<30% stromal cell positivity) or strong (>30% of stromal cell positivity). At least 10 independent fields/case were examined and statistically evaluated as described below.

cDNA Microarray Analysis

The ONCOMINE database and gene microarray analysis tool, a repository for published cDNA microarray data (50, 51), was interrogated (May 2011) for mRNA expression of decorin in non-neoplastic and bladder cancers. Statistical analysis of the differences in decorin expression between the aforementioned tissues was accomplished through use of ONCOMINE algorithms, which allow for multiple comparisons among different studies (50–52). Only studies with statistical analysis giving p < 0.05 were considered.

Solid Phase Binding Studies

Decorin protein core binding to the IGF-IR was assessed by ELISA assay. Briefly, purified IGF-IR (100 ng/well) was allowed to adhere to wells overnight at room temperature in the presence of carbonate buffer, pH 9.6. The plates were washed with PBS and incubated over night with serial dilutions of decorin core (from 0.2 to 400 nm). After ligand incubation, the plates were extensively washed with PBS, blocked with PBS and 1% BSA, and incubated with primary antibody against the N terminus of decorin and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Signal was developed using Sigma-Fast tablets (Sigma-Aldrich) and read at A450 nm. Serial dilutions of decorin protein core made in PBS were tested. Additional binding assays were performed mixing a constant concentration of decorin protein core (10 nm) with increasing concentrations of ZnCl2 (from 0 to 120 μm).

Decorin protein core binding with IGF-I was performed as described above, but the plates were coated with IGF-I (100 ng/ml) instead. In the displacement assay, plates were coated with IGF-IR (100 ng/ml) and then incubated with decorin protein core at a constant concentration (20 nm) together with IGF-I at increasing concentrations (0–400 nm).

Confocal Microscopy

Approximately 5 × 104 5637 cells were plated on 4-well chamber slides (BD Bioscences) and grown to full confluence in RPMI with 10% FBS at 37 °C. The cells were switched to RPMI serum-free medium 18 h prior to treatment with 50 ng/ml of IGF-I (R & D Systems), 200 nm decorin, or a combination of both for 10 and 60 min. The slides were then put on ice, rinsed twice with cold 1× PBS, and fixed/permeabilized with ice-cold methanol for 10 min. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with anti-IGF-IR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-caveolin-1 (BD Biosciences) antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, detection was determined using goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor® 488 and goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor® 564 (Invitrogen). Confocal analysis was performed on an Olympus IX70 microscope driven by Laser Sharp 2000 image software. The filters were set to 488 and 564 nm for dual channel imaging. All of the images were then analyzed using Image J and Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) software.

Detection of IGF-IR Activation and IGF-IR, IRS-1, and IRS-2 Levels

Serum-starved 5637 and T24 cells were preincubated with decorin at the designated concentrations (50–200 nm) for 1 h and then incubated with either SFM, IGF-I (50 ng/ml), IGF-I and decorin, or decorin alone for 10 min. To test the effect of decorin binding to the ligand, IGF-I was preincubated with 50–200 nm decorin core and then supplemented to cells. IGF-IR phosphorylation was detected by immunoblot using anti-phospho-Tyr1135/6 IGF-IR antibodies (R & D Systems). Total IGF-IR was assessed using anti-IGF-IR polyclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Total IGF-IR, IRS-1, and IRS-2 levels were determined after 24 h of IGF-I stimulation with or without 200 nm decorin. IGF-IR levels in 5637 cells were also assessed after 48 and 72 h. Anti-IRS-1 and anti-IRS-2 polyclonal antibodies were from Millipore. β-Actin was detected using anti-β-actin polyclonal antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

Migration, Wound, and Invasion Assays

Migration experiments were performed using HTS FluoroBloksTM inserts (Becton Dickinson) as previously described (19, 49, 53). The membranes were mounted on a slide, and migrated cells were counted and photographed with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M cell live microscope at the Kimmel Cancer Center Bioimaging Facility. For in vitro wound assays, the cells were seeded onto 35-mm plates in serum-containing medium until subconfluence and serum-starved for 24 h. The plates were then scratched with a thin disposable tip to generate a wound in the cells monolayer (19, 49, 53) and incubated in SFM or SFM supplemented with IGF-I, IGF-I, and decorin or decorin alone. The cells were analyzed and photographed after 24 h with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M cell live microscope using the Metamorph Image Acquisition and Analysis software (Universal Imaging). Cell invasion through a three-dimensional extracellular matrix was assessed using BD MatrigelTM-coated Invasion Chambers (BD Biocoat) (19, 49). After 24 h, the filters were washed, fixed, and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The cells that had invaded to the lower surface of the filter were counted under the microscope.

Detection of Activated Signaling Pathways

Serum-starved 5637 were preincubated with decorin for 1 h and then stimulated with IGF-I (50 ng/ml), IGF-I and decorin, or decorin alone for 10 min. The activation of p90RSK, Akt, ERK1/2, and p70S6k protein was analyzed by Western immunoblot using the PathScan Multiplex Western Mixture I (Cell Signaling Technology). ElF4E protein was used as a control to monitor the loading of the samples. Densitometric analysis was performed using the Image J program.

Statistical Analysis

The experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated at least three times. The results are expressed as means ± S.E. All of the statistical analyses were carried out with SigmaStat for Windows version 3.10 (Systat Software, Inc., Port Richmond, CA). The results were compared using the two-sided Student's t test. The differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

IGF-IR and Decorin Expression in Bladder Cancer

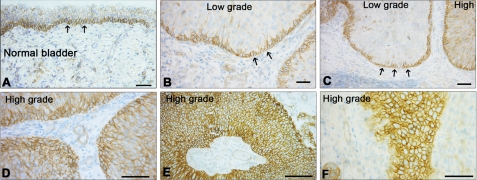

We have recently demonstrated that the IGF-IR is overexpressed in invasive bladder cancer tissues and promotes cell motility and invasion of bladder cancer cells (19). These results provide the first evidence that the IGF-IR plays a critical role in bladder cancer and may promote the transition to an invasive stage. However, our previous analysis only compared IGF-IR expression in invasive and normal bladder cancer tissues (19), and therefore we could not determine the role of the IGF-IR in bladder cancer progression. In this study, we have extended our immunohistochemical analysis on bladder cancer tissues derived from low and high grade bladder tumors and have immunostained 40 new cases of low and high grade (n = 20 each). In low grade bladder cancers, we found expression of the IGF-IR predominantly in the basal layers (Fig. 1, B and C), with a distribution similar to that of normal bladder (Fig. 1A). In contrast, high grade tumors showed a uniformly increased expression of IGF-IR, which was expressed throughout the tumor nodules (p < 0.001; Fig. 1, D–F). The results were nearly identical for all of the cases under investigation.

FIGURE 1.

Increased expression of IGF-IR correlates with advancement of urothelial neoplasia. A and B, immunohistochemistry of normal bladder (A) and low grade bladder cancer (B). Notice that the IGF-IR is expressed predominantly by the basal urothelium, where the stem cells reside (arrows). C, transition between low and high grade bladder carcinoma. Notice that in the high grade the IGF-IR is now expressed by all the neoplastic cells. D–F, representative images of high grade bladder cancers showing prominent IGF-IR expression in the large tumors as well as in the small infiltrating portions of the neoplasm. Paraffin-embedded tissue from 40 patients with low (n = 20) and high (n = 20) bladder carcinoma were stained with anti-IGF-IR (clone G11; Ventana Medical System). At least 10 independent fields/section were examined. Bars, 100 μm.

Next, we analyzed decorin expression in different publicly available bladder cancer microarray studies using the ONCOMINE database and gene microarray data analysis tool (50, 51). The analysis evaluated decorin mRNA expression levels for each of the individual studies as well as performing a summary statistic, taking into account the significance of the gene expression across the considered studies. In two independent data sets (54, 55) (Fig. 2A), there was a statistically significant decrease of decorin mRNA expression levels in primary bladder cancers compared with non-neoplastic controls. In the data set reported by Dyrskjøt et al. (54), there was a 3.5-fold decrease in decorin mRNA in superficial bladder cancer (p = 7.4 × 10−6) (Fig. 2A, left panel), whereas in the study by Sanchez-Carbayo et al. (55) (Fig. 2A, right panel), decorin mRNA levels were decreased 3.5-fold in infiltrating bladder cancer (p = 1.18 × 10−16) and ∼13-fold in superficial bladder cancer (p = 2.7 × 10−25).

FIGURE 2.

Decorin expression in normal and bladder cancer tissues. A, expression array analysis of multiple bladder cancer microarray data sets. Statistical significance was calculated using the ONCOMINE program (50, 51). In the study by Dyrskjøt et al. (54) (left panel), there was a 3.5-fold decrease in decorin mRNA in superficial bladder cancer (p = 7.4 × 10−6, t test: −4.952). In the study by Sanchez-Carbayo et al. (55) (right panel), decorin mRNA levels were decreased 3.5-fold in infiltrating bladder cancer (p = 1.18 × 10−16, t-Test: −9.449) and 13-fold in superficial bladder cancer (p = 2.7 × 10−25, t test: −17.066). B, immunohistochemical analysis of various bladder cancer tissues using an antibody directed toward the N terminus of human decorin or against the IGF-IR, as indicated. Notice that decorin is highly expressed in the submucosa of superficial bladder cancer and in the deep muscularis and deep tumor stroma. However, decorin is barely detectable in the stroma of low and high grade bladder tumors. Successive sections from the same cases show high expression of the IGF-IR. The images are representative of a total of 40 patients with low (n = 20) and high grade (n = 20) bladder carcinomas. At least 10 independent fields/section were examined. Bars, 100 μm.

To determine whether these independent mRNA studies would correlate with decorin expression, we performed immunohistochemical analysis of 40 cases of low and high grade bladder tumors in which we characterized IGF-IR expression (see above). Notably, strong decorin expression was detectable in the muscular layer of superficial bladder cancer, as well as deeply in the tunica muscularis and the preexisting stroma adjacent to tumors (Fig. 2B). However, decorin immunoreactivity was severely reduced in the tumor stroma of both low and high grade bladder cancer (Fig. 2B), in agreement with the microarray mRNA data discussed above. Statistical analysis of the dichotomized groups revealed a significant down-regulation of stromal decorin in both low and high grade tumors (p < 0.001 for both groups, n = 20 for each group, two-sided Student's t test). Notably, successive sections stained for IGF-IR showed marked expression of this receptor in area where decorin was either lost or undetectable (Fig. 2B). Even in areas of poorly differentiated bladder cancer with prominent stromal reaction, there was no detectable stromal decorin expression. The results were nearly identical for all of the cases under investigation. Collectively, these results suggest that loss of stromal decorin, at both the mRNA and protein levels, may contribute to bladder cancer progression, and this may correlate with increasing IGF-IR activity. However, it remains to be determined whether there is any causal link between low stromal decorin and enhanced IGF-IR expression/activity.

Decorin Binds IGF-IR and IGF-I at Distinct Sites

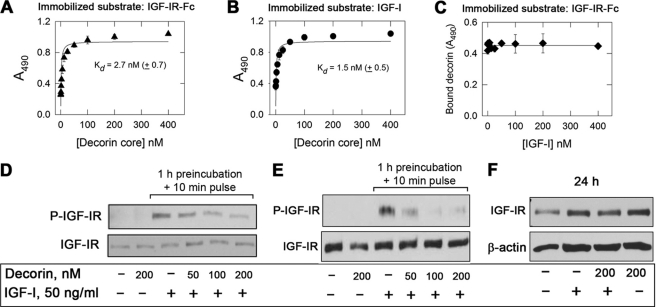

The previous results suggest that loss of decorin could be permissive for tumorigenesis by releasing the IGF-IR from a natural RTK repressor. Thus, to establish whether decorin may regulate IGF-IR activity in bladder cancer cells, we first tested whether decorin core could bind either the IGF-IR or its natural ligand IGF-I in a cell-free system. Decorin core bound with high affinity (Kd = 2.7 ± 0.7 nm) to the IGF-IR as determined by ELISA assays using a recombinant form of human IGF-IR as the immobilized substrate (Fig. 3A). The binding was not affected by the presence of the glycosaminoglycan chain insofar as decorin proteoglycan bound to the IGF-IR and IGF-I with similar affinities (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

Decorin protein core binds the IGF-IR and IGF-I at distinct sites and modulates IGF-IR activity. A and B, soluble decorin protein core binds to immobilized human recombinant IGF-IR and IGF-I in a saturable fashion. Solid phase ELISA assays were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” C, lack of displacement by increasing molar concentrations of IGF-I of a constant molar amount (20 nm) of decorin bound to IGF-IR. The values represent the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments run in triplicates. D, immunoblots of cells exposed to IGF-I and decorin or to a combination of both as indicated. Serum-starved 5637 cells were preincubated with decorin at the designated concentrations (50–200 nm) for 1 h and then incubated with either IGF-I (50 ng/ml) or IGF-I and decorin. Lane 2 represents a 10-min treatment with decorin alone. IGF-IR phosphorylation was detected by immunoblot using anti-Tyr1135/6 IGF-IR antibodies. Total IGF-IR was assessed using anti-IGF-IR polyclonal antibodies. E, immunoblots of cells exposed to IGF-I and/or decorin. IGF-I (50 ng/ml) was preincubated with decorin (50–200 nm) for 1 h and then supplemented to cells. Lane 2 represents a 10-min treatment with decorin alone. F, total IGF-IR levels determined after 24-h stimulation with IGF-I, IGF-I and decorin, or decorin alone. The blots are representative of three independent experiments.

Decorin core also bound to immobilized IGF-I with similar affinity (Kd = 1.5 ± 0.5 nm) (Fig. 3B). Notably, the IGF-IR-bound decorin (20 nm) could not be displaced by even a 20-fold molar excess of soluble IGF-I (Fig. 3C). Similarly, IGF-I bound to immobilized IGF-IR could not be displaced by molar excess of decorin core (supplemental Fig. S1C). This indicates that decorin binds IGF-IR in a region that does not overlap with the canonical binding site for IGF-I.

Because decorin is a Zn2+ metalloprotein (56), and this cation promotes the binding of decorin to fibrinogen, collagen, fibronectin (57), and myostatin (58), we performed binding experiments in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations (0–120 μm) of ZnCl2. Notably, we found no effect of Zn2+ in modulating the binding of recombinant decorin protein core to either IGF-I or IGF-IR (not shown), indicating that this protein-protein interaction is independent of Zn2+.

To further prove the binding of decorin to IGF-IR, we labeled decorin protein core with the infrared dye IRDye® 800CW (29) (supplemental Fig. S2A) and performed binding studies as above. The infrared-labeled protein core bound to immobilized IGF-IR in a saturable fashion (Kd = 84 ± 12.36 nm) (supplemental Fig. S2B), and its binding could be efficiently displaced by excess molar amounts of unlabeled decorin protein core (IC50 = 58 nm; supplemental Fig. S2C). Notably, the affinity of the binding of IR800-decorin to IGF-IR was lower than the one of the unlabeled protein. This is likely due to the modifications induced by the covalent linkage of the infrared dye to decorin that may reduce the binding affinity.

To further prove the specificity of our binding studies, we utilized, as negative control, recombinant LG3, the 26-kDa terminal globular domain of endorepellin (59). Under identical experimental conditions, IR800-labeled LG3 (supplemental Fig. S2D) bound in a nonsaturable linear fashion to IGF-IR (r2 = 0.99; supplemental Fig. S2E). This rules out a role for the His tag in the binding insofar as LG3 has a His tag as the decorin protein core, has a similar molecular mass as decorin, and was produced by the same human 293-EBNA cells as decorin.

Decorin Modulates IGF-IR Activity without Affecting Receptor Levels

Given this unusual binding of decorin to both ligand and receptor, we determined whether decorin may play a role in regulating IGF-IR activity. Thus, 5637 urothelial carcinoma-derived cells were first preincubated for 1 h with different concentrations of decorin (50–200 nm) and then stimulated for 10 min with IGF-I (50 ng/ml, ∼6.5 nm), a concentration previously shown to provide maximal IGF-IR stimulation (19, 60) Under these conditions, decorin inhibited IGF-I-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation at Tyr1135/6 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3D; p < 0.001 for the 200 nm decorin + IGF-I as compared with IGF-I alone, n = 3). Importantly, decorin alone had no effect on either IGF-IR phosphorylation at Tyr1135/6 or total receptor levels (Fig. 3, D and E, second lanes). Decorin inhibition of IGF-IR activity was also reproducible in T24 urothelial cancer cells (supplemental Fig. S3; p = 0.004 for the decorin + IGF-I as compared with IGF-I alone, n = 3).

Because decorin binds IGF-I, we repeated the same experiments after preincubating IGF-I with increasing concentrations of decorin for 1 h and then exposing the co-incubated ligands to the cells for 10 min. Preincubation of IGF-I with decorin severely decreased ligand-dependent IGF-IR activation levels in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3E; p < 0.001 for the 100 and 200 nm decorin + IGF-I as compared with IGF-I alone, n = 3). Notably, prolonged (24 h) exposure to decorin did not affect the stability of the IGF-IR in 5637 cells either alone or in the presence of IGF-I (Fig. 3F). To ensure that decorin did not affect receptor stability after prolonged stimulation, we tested by immunoblotting IGF-IR levels in 5637 cells after 48 and 72 h of incubation with IGF-I, IGF-I and decorin (200 nm), or decorin alone (200 nm). Compared with 24 h, IGF-I induced modest degradation of the IGF-IR at 48 h, which was slightly increased at 72 h. Decorin had no effect on IGF-IR stability either alone or in combination with IGF-I (not shown).

Under identical experimental conditions of Fig. 3F, MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma cells responded in a similar fashion insofar as the total IGF-IR was not down-regulated, but its activation by IGF-I was attenuated by decorin (supplemental Fig. S4). Moreover, in HeLa squamous carcinoma cells, decorin did not induce down-regulation of the IGF-IR under conditions that led to a marked physical down-regulation of Met and β-catenin (not shown).

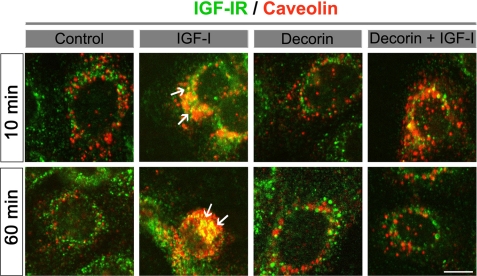

We conclude that decorin affects IGF-IR function in a manner that substantially differs from its known activity on EGFR and Met. In the latter case, both exogenous and de novo expression of decorin led to a physical down-regulation of these two RTKs via caveolin-mediated endocytosis (24–29). To strengthen this hypothesis, we utilized laser confocal microscopy. We found that decorin did not induce co-localization of IGF-IR and caveolin-1 either after 10 or 60 min of treatment in 5637 cells. In contrast, as expected, there was a significant co-localization of IGF-IR and caveolin-1 evoked by IGF-I (Fig. 4, arrows), in agreement with previous reports (61, 62). Interestingly, we noticed that after 10 min of treatment with IGF-I and decorin together, there was little co-localization of IGF-IR and caveolin-1 and that this co-localization was totally disrupted after 60 min. This suggests that decorin action on IGF-IR is slower than the effects mediated by IGF-I on the receptor. Collectively, these results suggest that decorin regulates the IGF-IR axis in bladder cancer cells, and perhaps other carcinoma cells, by modulating both ligand binding and receptor activation.

FIGURE 4.

Decorin does not induce IGF-IR/caveolin-1 co-localization. 5637 cells were treated with IGF-I (50 ng/ml), decorin (200 nm), or a combination of both for 10 or 60 min. After fixation, the cells were labeled with a rabbit anti-IGF-IR (green) and a mouse anti-caveolin-1 (red) and imaged by confocal laser microscopy. The pictures represent the merged fields and show co-localization (yellow, arrows) of IGF-IR and caveolin-1 in the IGF-I-treated cells but not in the decorin ones. Bar, 10 μm.

Decorin Enhances IGF-I-dependent IRS-1 Down-regulation

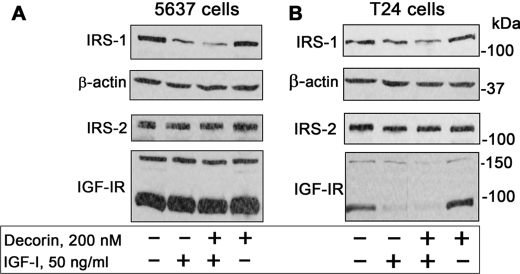

One of the major downstream effectors of the IGF-IR signaling pathway is the docking protein insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1), which upon ligand-induced recruitment to the IGF-IR regulates the activation of the PI3K and Akt pathways. This activity is critical for IGF-IR-dependent biological effects, including cell proliferation and transformation (63, 64). However, it is not known whether decorin could affect the IGF-IR axis by regulating the stability/activation of downstream signaling effectors. To this end, we determined IRS-1 protein levels after prolonged exposure to IGF-I and/or decorin. We found that chronic (24 h) IGF-I stimulation promoted IRS-1 degradation of both 5637 (Fig. 5A) and T24 (Fig. 5B) cells, in agreement with published data (65, 66). However, this effect was enhanced by supplementing IGF-I with 200 nm decorin (Fig. 5; p < 0.01 for the decorin + IGF-I as compared with IGF-I alone, n = 3). In contrast, decorin alone had no effect in regulating IRS-1 stability (Fig. 5). Notably, although decorin enhanced IRS-1 degradation, it had no effect in regulating the levels of either IRS-2 (Fig. 5) or Shc proteins (not shown), two established components of the IGF-IR signaling pathway (67–69). The only difference in behavior between 5637 and T24 cells was that prolonged IGF-I stimulation of T24 cells induced down-regulation of the IGF-IR, a process not affected by decorin (Fig. 5B). Collectively, these results provide the first evidence of a role for decorin in regulating ligand-dependent stability of IRS-1 and suggest that decorin may regulate the IGF-IR pathway not only by directly affecting receptor activation but also by modulating the stability of downstream signaling proteins.

FIGURE 5.

Decorin enhances IGF-I-induced IRS-1 degradation. Shown are immunoblots of total cell lysates from 5637 (A) or T24 (B) urothelial carcinoma cells using antibodies against IRS-1, IRS-2, β-actin, and IGF-IR. The cells were exposed to decorin and/or IGF-I as designated for 24 h. The blots are representative of three independent experiments. The bands above 160 and ∼95 kDa in the IGF-IR blots represent the precursor and β subunit of the IGF-IR, respectively. Notice that decorin alone has no effect on IRS-1 levels but has an additive effect in down-regulating IRS-1 when supplemented together with IGF-I.

Decorin Regulates IGF-IR-dependent Biological Responses in Urothelial Cancer Cells

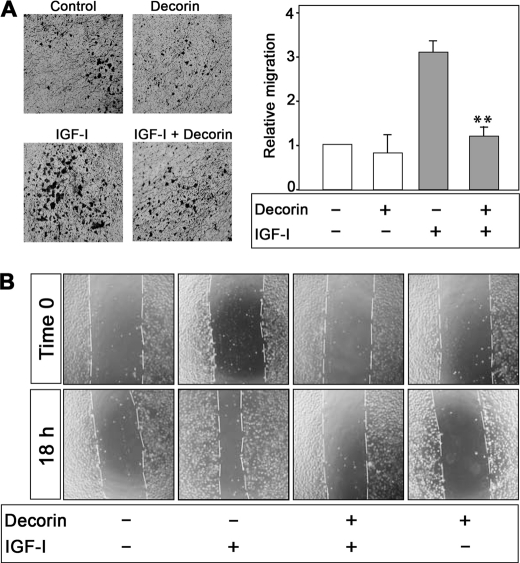

We have recently shown that the IGF-IR acts as a “scatter factor” in urothelial cancer cells and markedly enhances cell motility and invasion without affecting cell proliferation (19). Because decorin inhibits IGF-I-evoked activation of the IGF-IR, we hypothesized that decorin could also affect the ability of the IGF-IR to promote motility and invasion. Therefore, we determined ligand-induced motility of 5637 cells in the presence or absence of recombinant decorin. Decorin alone (200 nm) had no effect on cell motility in contrast to IGF-I, which induced a 3-fold increase in migration compared with controls (Fig. 6A). Decorin significantly inhibited the ability of IGF-I to promote migration, and these effects were comparable with the motility of unstimulated 5637 cells (p < 0.01; Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Decorin inhibits IGF-I-induced migration and wound healing of 5637 urothelial carcinoma-derived cells. A, migration assays on 5637 cells were performed as previously described (19, 49). The data are expressed as relative migration over SFM (normalized to 1). The values represent the means ± S.D. of four independent experiments run in duplicate (**, p < 0.01). B, representative images of in vitro wound healing experiments following an 18-h exposure to decorin and/or IGF-I as indicated. The cells were analyzed with live cell microscopy using Metamorph image acquisition and analysis software (Universal Imaging) (×100). Ten fields/plates were examined.

Next, we determined the ability of 5637 cells to migrate in response to IGF-I and decorin using an in vitro “wound healing” assay (19, 49). In contrast to controls, IGF-I evoked a substantial migration into the denuded area (Fig. 6B). This effect was significantly counteracted by co-incubation of IGF-I with recombinant decorin (p < 0.05 for the decorin + IGF-I as compared with IGF-I alone, n = 3). As in the migration assay described above, decorin alone had no effect on cell motility. Thus, decorin plays a critical role in regulating the ability of IGF-I to promote migration and lateral motility (wound healing) in cancer urothelial cells.

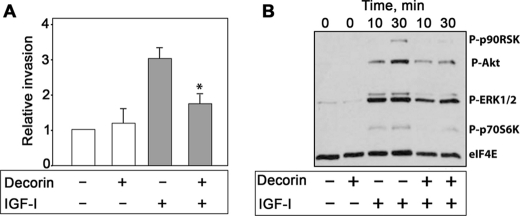

Decorin Regulates IGF-IR-dependent Invasion through a Three-dimensional Matrix and Affects Signaling Events Downstream of the Receptor

The acquisition of an invasive phenotype is a critical step for tumor progression (70), and activation of the IGF-IR strongly enhances the ability of urothelial cancer cells to invade through extracellular matrix (19). We used Matrigel-coated filters to examine decorin action on IGF-I-dependent invasive migration through a three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Decorin alone had no effect on the invasive capability of 5637 cells, whereas IGF-I induced a marked increase in the cell ability to invade a three-dimensional matrix (Fig. 7A). IGF-I-induced invasiveness of 5637 cells was instead inhibited by decorin (p < 0.05; Fig. 7A), even though the effect of decorin was not as profound as the inhibition of cell migration. In addition, we discovered that decorin markedly affected IGF-I-dependent activation of the two major pathways critical for IGF-IR-dependent motility and invasion (19). Decorin severely attenuated IGF-I-stimulated activation of Akt and ERK1/2 pathways and a consequent inhibition of downstream targets p70S6K and p90RSK, respectively (Fig. 7B). Notably, decorin alone had no effect on the activation of these signaling proteins (Fig. 7B). Collectively, these results suggest that decorin action on IGF-IR activation strongly affects downstream signaling, thereby negatively regulating IGF-I-dependent biological events in bladder cancer cells.

FIGURE 7.

Decorin inhibits IGF-IR-dependent invasive ability of 5637 cells and inhibits IGF-I-induced downstream signaling. A, quantification of invading 5637 cells plated on Matrigel-coated Transwells. Invasion was analyzed at 24 h. The data are expressed as relative migration over SFM (normalized to 1). The values represent the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments run in duplicate (*, p < 0.05). B, immunoblots of total 5637 cell lysates using PathScan Multiplex Western Mixture I (Cell Signaling), which detects phosphorylation of p90RSK, Akt, ERK1/2, and S6 ribosomal proteins. The eIF4E serves as loading control. The cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then stimulated with IGF-I (50 ng/ml), IGF-I and decorin (200 nm), or decorin alone (200 nm) for the indicated time intervals. The blot is representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although bladder cancer is one of the most common malignancies (1), the molecular mechanisms that determine malignant transformation of urothelial cells in the bladder are still poorly characterized. Although IGF-IR is markedly overexpressed in invasive human bladder cancer, activation of the IGF-IR does not evoke in vitro cell proliferation (19), suggesting that the IGF-IR may not be critical for bladder cancer initiation but may play a more prevalent role in bladder cancer progression to the invasive and possibly metastatic phenotype. The proteoglycan decorin has been shown to regulate IGF-IR function in normal cells (44–46), but there are no data demonstrating decorin action on the IGF-IR in any cancer model.

In the present study we investigated whether decorin would modulate IGF-IR activity in urothelial cancer cells. We demonstrate that: (i) IGF-IR levels increase with bladder cancer progression, (ii) decorin mRNA levels are severely reduced in urothelial carcinoma-derived tissues compared with normal tissue, (iii) decorin expression is markedly reduced in bladder cancer tissues and inversely correlates with IGF-IR levels, (iv) decorin protein core binds with high affinity to both the ligand IGF-I and the IGF-IR at distinct sites, (v) decorin negatively regulates IGF-IR activation without affecting receptor protein levels, (vi) decorin enhances IGF-I-mediated down-regulation of IRS-1 without affecting either IRS-2 or Shc protein stability, (vii) decorin severely decreases the ability of 5637 urothelial carcinoma-derived cells to migrate and invade in response to IGF-I stimulation, and (viii) decorin affects IGF-IR-dependent activation of downstream signaling proteins Akt and MAPK.

Using the ONCOMINE program (50, 51), we have analyzed decorin mRNA levels in available microarray data sets and found that decorin expression is considerably reduced in urothelial carcinoma vis-à-vis normal bladder tissues in two independent data sets (54, 55). In addition, by immunohistochemical analysis of low and high grade bladder cancer specimens, we discovered that decorin expression is almost totally lost in the tumor stroma compared with normal bladder and inversely correlates with IGF-IR levels, whose expression is markedly increased with bladder cancer progression. These findings are in agreement with the hypothesis that decorin, a stromal-specific marker, could inhibit tumor cell growth via paracrine down-regulation of RTKs involved in cell growth and survival including the EGFR and other members of the ErbB family of RTKs (40, 71), as well as Met (28).

Decorin regulates the IGF-I system in endothelial cells, renal fibroblasts, and human tubular epithelial cells, but the significance of decorin regulation of the IGF-IR signaling network is not clear. In endothelial cells, decorin promotes IGF-IR phosphorylation and IGF-IR-dependent Akt activation, but it also induces subsequent receptor degradation (44). In addition, decorin induces IGF-IR-dependent endothelial cells adhesion and migration on fibrillar collagen (72). In renal fibroblasts, decorin regulates the synthesis of fibrillin-1 through the IGF-IR/mTOR/p70S6K signaling pathway (45). In extravillus trophoblasts, instead, decorin inhibits migration by promoting IGF-IR phosphorylation and activation in a dose-dependent manner, but the anti-proliferative effect of decorin is IGF-IR-independent (73). Previous studies have reported that decorin binds with high affinity to both IGF-I and IGF-IR (44, 45). However, these studies utilized immunoprecipitated receptor complexes using an antibody against the intracellular domain of the β-subunit of the IGF-IR (44, 45). Thus, there is the possibility of nonspecific binding to other co-precipitated proteins. In the present study, we expand and confirm a specific binding of decorin to both the IGF-I and its receptor by using recombinant proteins in a cell-free system. Because of the ability of decorin to bind both IGF-I and its receptor, it is also possible that there is the formation of a trimolecular signaling complex, with decorin acting as negative regulator.

Decorin function is reminiscent of IGF-binding proteins (IGF-BPs), which either positively or negatively modulate the IGF-I system, depending on cell and tissue models (74). IGF-BPs are expressed in bladder (75), but whether decorin may bind to IGF-I/IGF-BP complexes and whether the presence of IGF-BPs may affect in vivo decorin action in bladder have not been established. Future experiments are warranted to address this issue.

The studies discussed above were all performed with nontransformed cells, whereas our results show that the mechanisms of decorin action on IGF-IR signaling differ considerably in the many cancer cell lines utilized in this study. In urothelial carcinoma-derived cells, decorin alone has no effect on receptor activation and cell migration but inhibits ligand-induced IGF-IR phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner and reduces IGF-I-mediated activation of downstream effectors, like Akt and ERK1/2. These two effectors are key molecules regulating migration and invasion in response to IGF-I. Significantly, prolonged decorin stimulation has no effects on IGF-IR stability in 5637, T24, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cells, indicating that in several cancer cells, the mechanism of decorin action on the IGF-IR differs not only from its activity on nontransformed cells where IGF-IR phosphorylation is followed by degradation (44) but also from decorin action on EGFR and Met, which usually leads to intracellular degradation of these two RTKs (24–28).

We have previously shown that in fibroblasts overexpressing the IGF-IR, ligand-induced IGF-IR ubiquitination and internalization lead to receptor degradation (76). Because decorin did not affect IGF-IR levels, we have not determined whether decorin may affect IGF-I-induced receptor internalization from the cell surface. However, because IGF-IR phosphorylation occurs at the plasma membrane (76), we hypothesize that decorin may inhibit IGF-IR phosphorylation by enhancing receptor internalization, thereby decreasing the IGF-IR pool at the cell surface. The internalized IGF-IR would then be recycled to the cell surface and not sorted for degradation. Indeed, in 5637 cells, decorin alone does not induce IGF-IR internalization and degradation via caveolar-mediated endocytosis as the natural ligand IGF-I. However, as we speculated, further experiments are required to elucidate a possible role of decorin in promoting IGF-IR recycling.

We have discovered for the first time that decorin enhances IGF-I-induced IRS-1 down-regulation without affecting the stability of IRS-2 or Shc, two other key components of IGF-IR downstream signaling (68, 77). Thus, decorin may negatively regulate the IGF-IR signaling pathway not only by directly binding the receptor and modulating its activity but also by affecting the stability of critical downstream effectors. It is well established that insulin and IGF-I-dependent IRS-1 degradation is regulated by IGF-IR activation, which mediates subsequent PI3K-dependent phosphorylation of IRS-1 on serine residues (65, 66). It is reasonable to speculate that decorin, by reducing IGF-IR activity, may reduce the level of IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, thus increasing the endogenous pool of serine-phosphorylated IRS-1. Decorin may additionally enhance the ability of an IGF-IR downstream effector protein to promote IGF-I-dependent serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, thereby enhancing IRS-1 degradation. Decorin alone has no effect on IRS-1 stability, clearly indicating that decorin action on IRS-1 levels is independent from its action on other RTKs, which may indirectly contribute to affect IRS-1 stability.

Our results of the immunohistochemistry analysis of decorin and IGF-IR levels are reminiscent of previous work (44), which reported elevated tubuloepithelial IGF-IR expression in ligated kidneys from Dcn−/− mice as compared with wild type animals. Because the results from in vitro experiments indicated that decorin activates common signaling pathways with the IGF-IR (44), increased IGF-IR levels were attributed to a compensatory mechanism for the lack of decorin to protect tubular epithelial cells from apoptosis. Our data support a different model for decorin and IGF-IR interaction in bladder urothelium. In normal tissues/cells, the IGF-IR is expressed, although at low levels. Decorin expression in normal tissues/cells likely contributes to control the levels of IGF-IR activation. In urothelial carcinomas, IGF-IR expression increases with tumor grade, and decorin loss indirectly induces IGF-IR activity and signaling, thereby promoting enhanced cellular motility, invasion, and cancer progression. Thus, decorin may work as a natural antagonist of the IGF-IR in bladder cancer and perhaps in other types of cancer where this receptor plays a central role.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Pal for help with immunoblotting and A. Goyal for providing the IR800-labeled LG3.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 DK068419 (to A. M.) and RO1 CA39481, RO1 CA47282, and RO1 CA120975 (to R. V. I.). This work was also supported by the Benjamin Perkins Bladder Cancer Fund and the Martin Greitzer Fund.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- IGF-I

- insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGF-IR

- IGF receptor I

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- IRS

- insulin receptor substrate

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- SFM

- serum-free medium

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- IGF-BP

- IGF-binding proteins.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. (2010) CA-Cancer J. Clin. 60, 277–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knowles M. A. (2008) Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 13, 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitra A. P., Cote R. J. (2009) Annu. Rev. Pathol. 4, 251–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scher C. D., Stone M. E., Stiles C. D. (1979) Nature 281, 390–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stiles C. D., Isberg R. R., Pledger W. J., Antoniades H. N., Scher C. D. (1979) J. Cell Physiol. 99, 395–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baserga R. (1995) Cancer Res. 55, 249–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baserga R. (2000) Oncogene 19, 5574–5581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baserga R., Hongo A., Rubini M., Prisco M., Valentinis B. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1332, F105–F126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baker J., Liu J. P., Robertson E. J., Efstratiadis A. (1993) Cell 75, 73–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu J. P., Baker J., Perkins A. S., Robertson E. J., Efstratiadis A. (1993) Cell 75, 59–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eggenschwiler J., Ludwig T., Fisher P., Leighton P. A., Tilghman S. M., Efstratiadis A. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 3128–3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Roith D., Karas M., Yakar S., Qu B. H., Wu Y., Blakesley V. A. (1999) Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 1, 25–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Le Roith D. (2000) Growth Horm. IGF. Res. 10, (Suppl. A) S12–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guvakova M. A., Surmacz E. (1997) Exp. Cell Res. 231, 149–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mauro L., Sisci D., Bartucci M., Salerno M., Kim J., Tam T., Guvakova M. A., Ando S., Surmacz E. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 252, 439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doerr M. E., Jones J. I. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2443–2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim H. J., Litzenburger B. C., Cui X., Delgado D. A., Grabiner B. C., Lin X., Lewis M. T., Gottardis M. M., Wong T. W., Attar R. M., Carboni J. M., Lee A. V. (2007) Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 3165–3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chitnis M. M., Yuen J. S., Protheroe A. S., Pollak M., Macaulay V. M. (2008) Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 6364–6370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Metalli D., Lovat F., Tripodi F., Genua M., Xu S. Q., Spinelli M., Alberghina L., Vanoni M., Baffa R., Gomella L. G., Iozzo R. V., Morrione A. (2010) Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2997–3006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iozzo R. V. (1997) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 141–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schaefer L., Iozzo R. V. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21305–21309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iozzo R. V., Schaefer L. (2010) FEBS J. 277, 3864–3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Theocharis A. D., Skandalis S. S., Tzanakakis G. N., Karamanos N. K. (2010) FEBS J. 277, 3904–3923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iozzo R. V., Moscatello D. K., McQuillan D. J., Eichstetter I. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 4489–4492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santra M., Reed C. C., Iozzo R. V. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35671–35681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Santra M., Eichstetter I., Iozzo R. V. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35153–35161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Csordás G., Santra M., Reed C. C., Eichstetter I., McQuillan D. J., Gross D., Nugent M. A., Hajnóczky G., Iozzo R. V. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32879–32887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goldoni S., Humphries A., Nyström A., Sattar S., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Ireton K., Iozzo R. V. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 185, 743–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buraschi S., Pal N., Tyler-Rubinstein N., Owens R. T., Neill T., Iozzo R. V. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 42075–42085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iozzo R. V., Chakrani F., Perrotti D., McQuillan D. J., Skorski T., Calabretta B., Eichstetter I. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3092–3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bi X., Tong C., Dockendorff A., Bancroft L., Gallagher L., Guzman G., Iozzo R. V., Augenlicht L. H., Yang W. (2008) Carcinogenesis 29, 1435–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nash M. A., Loercher A. E., Freedman R. S. (1999) Cancer Res. 59, 6192–6196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Biglari A., Bataille D., Naumann U., Weller M., Zirger J., Castro M. G., Lowenstein P. R. (2004) Cancer Gene Ther. 11, 721–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reed C. C., Gauldie J., Iozzo R. V. (2002) Oncogene 21, 3688–3695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tralhão J. G., Schaefer L., Micegova M., Evaristo C., Schönherr E., Kayal S., Veiga-Fernandes H., Danel C., Iozzo R. V., Kresse H., Lemarchand P. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 464–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seidler D. G., Goldoni S., Agnew C., Cardi C., Thakur M. L., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Iozzo R. V. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26408–26418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moscatello D. K., Santra M., Mann D. M., McQuillan D. J., Wong A. J., Iozzo R. V. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 406–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu J. X., Goldoni S., Bix G., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Reed C. C., Iozzo R. V. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32468–32479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reed C. C., Waterhouse A., Kirby S., Kay P., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Iozzo R. V. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goldoni S., Seidler D. G., Heath J., Fassan M., Baffa R., Thakur M. L., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Iozzo R. V. (2008) Am. J. Pathol. 173, 844–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Araki K., Wakabayashi H., Shintani K., Morikawa J., Matsumine A., Kusuzaki K., Sudo A., Uchida A. (2009) Oncology 77, 92–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shintani K., Matsumine A., Kusuzaki K., Morikawa J., Matsubara T., Wakabayashi T., Araki K., Satonaka H., Wakabayashi H., Iino T., Uchida A. (2008) Oncol. Rep. 19, 1533–1539 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hu Y., Sun H., Owens R. T., Wu J., Chen Y. Q., Berquin I. M., Perry D., O'Flaherty J. T., Edwards I. J. (2009) Neoplasia 11, 1042–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schönherr E., Sunderkötter C., Iozzo R. V., Schaefer L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15767–15772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schaefer L., Tsalastra W., Babelova A., Baliova M., Minnerup J., Sorokin L., Gröne H. J., Reinhardt D. P., Pfeilschifter J., Iozzo R. V., Schaefer R. M. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170, 301–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Merline R., Lazaroski S., Babelova A., Tsalastra-Greul W., Pfeilschifter J., Schluter K. D., Gunther A., Iozzo R. V., Schaefer R. E., Schaefer L. (2009) J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 60, (suppl. 4), 5–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Danielson K. G., Baribault H., Holmes D. F., Graham H., Kadler K. E., Iozzo R. V. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 136, 729–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Goldoni S., Owens R. T., McQuillan D. J., Shriver Z., Sasisekharan R., Birk D. E., Campbell S., Iozzo R. V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6606–6612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lovat F., Bitto A., Xu S. Q., Fassan M., Goldoni S., Metalli D., Wubah V., McCue P., Serrero G., Gomella L. G., Baffa R., Iozzo R. V., Morrione A. (2009) Carcinogenesis 30, 861–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rhodes D. R., Yu J., Shanker K., Deshpande N., Varambally R., Ghosh D., Barrette T., Pandey A., Chinnaiyan A. M. (2004) Neoplasia 6, 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rhodes D. R., Yu J., Shanker K., Deshpande N., Varambally R., Ghosh D., Barrette T., Pandey A., Chinnaiyan A. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9309–9314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xin W., Rhodes D. R., Ingold C., Chinnaiyan A. M., Rubin M. A. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 162, 255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Monami G., Emiliozzi V., Bitto A., Lovat F., Xu S. Q., Goldoni S., Fassan M., Serrero G., Gomella L. G., Baffa R., Iozzo R. V., Morrione A. (2009) Am. J. Pathol. 174, 1037–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dyrskjøt L., Kruhøffer M., Thykjaer T., Marcussen N., Jensen J. L., Møller K., Ørntoft T. F. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 4040–4048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sanchez-Carbayo M., Socci N. D., Lozano J., Saint F., Cordon-Cardo C. (2006) J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 778–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang V. W., LaBrenz S. R., Rosenberg L. C., McQuillan D., Höök M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12454–12460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dugan T. A., Yang V. W., McQuillan D. J., Höök M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13655–13662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Miura T., Kishioka Y., Wakamatsu J., Hattori A., Hennebry A., Berry C. J., Sharma M., Kambadur R., Nishimura T. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 340, 675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Iozzo R. V., Sanderson R. D. (2011) J. Cell Mol. Med. 15, 1013–1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morrione A., Valentinis B., Resnicoff M., Xu S., Baserga R. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26382–26387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Monami G., Emiliozzi V., Morrione A. (2008) J. Cell Physiol. 216, 426–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salani B., Passalacqua M., Maffioli S., Briatore L., Hamoudane M., Contini P., Cordera R., Maggi D. (2010) PLoS One 5, e14157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sun X. J., Crimmins D. L., Myers M. G., Jr., Miralpeix M., White M. F. (1993) Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 7418–7428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rose D. W., Saltiel A. R., Majumdar M., Decker S. J., Olefsky J. M. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 797–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Haruta T., Uno T., Kawahara J., Takano A., Egawa K., Sharma P. M., Olefsky J. M., Kobayashi M. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 783–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee A. V., Gooch J. L., Oesterreich S., Guler R. L., Yee D. (2000) Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 1489–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sasaoka T., Rose D. W., Jhun B. H., Saltiel A. R., Draznin B., Olefsky J. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13689–13694 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. White M. F. (1998) Mol. Cell Biochem. 182, 3–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. White M. F. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 283, E413–E422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Guo W., Giancotti F. G. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 816–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Goldoni S., Iozzo R. V. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 123, 2473–2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fiedler L. R., Schönherr E., Waddington R., Niland S., Seidler D. G., Aeschlimann D., Eble J. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17406–17415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Iacob D., Cai J., Tsonis M., Babwah A., Chakraborty C., Bhattacharjee R. N., Lala P. K. (2008) Endocrinology 149, 6187–6197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jogie-Brahim S., Feldman D., Oh Y. (2009) Endocr. Rev. 30, 417–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Miyake H., Hara I., Yamanaka K., Muramaki M., Eto H. (2005) BJU. Int. 95, 987–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Vecchione A., Marchese A., Henry P., Rotin D., Morrione A. (2003) Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 3363–3372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Baserga R., Morrione A. (1999) J. Cell. Biochem. 32/33, 68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.