Abstract

Long-lasting mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) openings damage mitochondria, but transient mPTP openings protect against chronic cardiac stress. To probe the mechanism, we subjected isolated cardiac mitochondria to gradual Ca2+ loading, which, in the absence of BSA, induced long-lasting mPTP opening, causing matrix depolarization. However, with BSA present to mimic cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins, the mitochondrial population remained polarized and functional, even after matrix Ca2+ release caused an extramitochondrial free [Ca2+] increase to >10 μm, unless mPTP openings were inhibited. These findings could be explained by asynchronous transient mPTP openings allowing individual mitochondria to depolarize long enough to flush accumulated matrix Ca2+ and then to repolarize rapidly after pore closure. Because subsequent matrix Ca2+ reuptake via the Ca2+ uniporter is estimated to be >100-fold slower than matrix Ca2+ release via mPTP, only a tiny fraction of mitochondria (<1%) are depolarized at any given time. Our results show that transient mPTP openings allow cardiac mitochondria to defend themselves collectively against elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels as long as respiratory chain activity is able to balance proton influx with proton pumping. We found that transient mPTP openings also stimulated reactive oxygen species production, which may engage reactive oxygen species-dependent cardioprotective signaling.

Keywords: Calcium, Cardiac Metabolism, Hypoxia, Ischemia, Mitochondria, Oxidative Stress, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Calcium Signaling, Cardioprotection, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore

Introduction

A key mechanism involved in cardiac injury is the mitochondrial permeability transition, due to the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (mPTP)3 in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM). The permeability transition has been shown to occur upon reperfusion of the ischemic heart (1), and its prevention is thought to be an important component of ischemic and pharmacologic pre-conditioning and post-conditioning (PC), the most powerful forms of cardioprotection known (2–6). Supporting this idea, mPTP inhibitors such as cyclosporine A (CsA) reduce ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (7), and genetic ablation of a critical mPTP component, cyclophilin D (CyPD), confers chronic protection against I/R injury, which is not further enhanced by CsA or ischemic PC (8).

Although long-lasting mPTP opening inevitably causes mitochondrial injury, evidence has been presented that mPTP can also open transiently, which may have beneficial effects, such as releasing accumulated Ca2+ from the matrix (9–11), ultimately delaying the onset of long-lasting, large conductance mPTP opening. Two recent findings provide strong support for a protective role of transient mPTP opening. First, CyPD knock-out (KO) mice, which are chronically protected against I/R injury (8), develop heart failure more rapidly in response to transaortic constriction or cross-breeding with some cardiomyopathic strains (12) but not all (13). These mice had elevated mitochondrial Ca2+ content, suggesting a defect in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling related to loss of mPTP function, with associated metabolic abnormalities. Second, whereas CsA given during prolonged ischemia reduces I/R injury (7), paradoxically, CsA (or sanglifehrin A) administered during ischemic or pharmacologic PC episodes blocks cardioprotection (6, 14, 15). This finding is reminiscent of reactive oxygen species (ROS), in which ROS scavengers given during prolonged ischemia reduce I/R injury, but ROS scavengers given during ischemic or pharmacologic PC episodes block cardioprotection (16). Thus, a picture is emerging that, similar to ROS, mPTP opening is a two-edged sword, with both protective and deleterious actions.

In this study, we used isolated cardiac mitochondria to explore the protective role of mPTP in mitochondrial Ca2+ handling. We present evidence that cardiac mitochondria can tolerate markedly elevated levels of extramitochondrial free [Ca2+] without collectively dissipating the average mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) as long as IMM leak is kept low by BSA to mimic fatty acid-binding proteins normally present in the cytoplasm. The mechanism involves mitochondria utilizing asynchronous transient mPTP openings to depolarize long enough to flush accumulated matrix Ca2+ without losing essential matrix metabolites such as NADH, after which they rapidly repolarize. If the subsequent rate of matrix Ca2+ reuptake via the Ca2+ uniporter is slow compared with the Ca2+-flushing rate, then only a small fraction (<1%) of the mitochondria are depolarized at any given point in time. We also found that when transient mPTP openings are induced by Ca2+ loading, mitochondrial ROS production increases markedly, which may provide a link between loss of mPTP function and loss of cardioprotection when hearts are exposed to mPTP blockers during PC episodes (6, 14, 15).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mitochondrial Isolation

Mitochondria were isolated from adult 2–3-kg New Zealand White rabbit hearts or wild-type and genetically altered mice by homogenization and differential centrifugation as described previously (17) and were resuspended in EGTA-free homogenization buffer (250 mm sucrose, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) with Tris base) to yield 30–50 mg of mitochondrial protein/ml. Mitochondria were incubated on ice and used within 5 h after isolation.

Isolated Mitochondrial Studies

All measurements were carried out using a customized Ocean Optics fiber optic spectrofluorometer in a continuously stirred cuvette, open to atmospheric air to permit O2 diffusion into the buffer, and maintained at room temperature (22–24 °C). Mitochondria (0.3–0.6 mg/ml) were added to the cuvette containing standard buffer consisting of 120 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) with Tris base. In some experiments, KCl was replaced with 250 mm sucrose. The partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) in the buffer was continuously recorded via an Ocean Optics FOXY-AL300 fiber optic oxygen sensor inserted through the same hole. Under these conditions, buffer [O2] depends on O2 consumption by mitochondria relative to the rate of O2 diffusion from air into the buffer. When consumption is balanced with diffusion, the O2 level remains stable. The effect of stirring speed on the rate of O2 diffusion into the buffer and how it is balanced with O2 consumption and O2 sensor calibration have been described in detail previously (18). Membrane potential (ΔΨm) was recorded using tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM; 400 nm, excitation and emission wavelengths of 545 and 580 nm, respectively) or alternatively with a tetraphenylphosphonium electrode (World Precision Instruments). Ca2+ uptake and efflux were recorded with a Ca2+ electrode (World Precision Instruments) or alternatively with low affinity Ca2+ dye (Calcium Green-5N). H2O2 production was measured using Amplex Red (10 μm) and horseradish peroxidase (0.2 units) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 545 and 590 nm, respectively. Matrix swelling/shrinkage was measured by light scattering at 540 nm, and protein content was determine using the Lowry method. Pyruvate, malate, and glutamate were added as free acids buffered with Tris (pH 7.4). BSA was added at a final concentration of 1 or 0.5 mg/ml, and added Pi was 2.5 mm unless indicated otherwise.

RESULTS

Ca2+ Loading Induces mPTP-mediated Matrix Ca2+ Release without Collective ΔΨm Dissipation if IMM Leak Is Low

ΔΨm depolarization induced by Ca2+ loading is an established method for testing the susceptibility of isolated mitochondria to mPTP opening. Consistent with this classic assay, we found that when we subjected isolated energized cardiac mitochondria to successive Ca2+ pulses, ΔΨm depolarization and matrix Ca2+ release occurred simultaneously (Fig. 1A). Note that O2 consumption became severely depressed during ΔΨm dissipation but rapidly increased with NADH addition (0.1 mm). This indicates that the IMM was permeable to NAD/NADH, indicative of long-lasting mPTP opening in the full conductance mode (Mr cutoff of ∼1500). Pi addition was also unable to promote mitochondrial Ca2+ re-accumulation (data not shown).

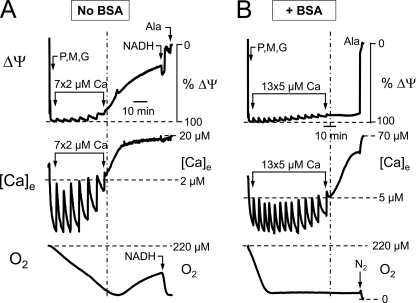

FIGURE 1.

Transient mPTP openings allow energized isolated mitochondria to tolerate elevated extramitochondrial [Ca2+] without collective ΔΨm dissipation when BSA is present. Mitochondria were added to KCl buffer (without Pi) at the beginning of the trace, followed by Complex I substrates pyruvate (P), malate (M), and glutamate (G) (3.5 mm each), while recording TMRM fluorescence (upper), extramitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca]e; middle), and O2 (lower). A, during seven successive 2 μm Ca2+ additions (between arrows), extramitochondrial [Ca2+] initially returned to the base-line level after each Ca2+ pulse until mitochondria then released matrix Ca2+ (dashed vertical line), which rose to >10 μm. In the absence of BSA, matrix Ca2+ release was accompanied by ΔΨm dissipation and decreased O2 consumption due to mPTP opening in the large conductance mode. B, in the presence of BSA (1 mg/ml), however, the average ΔΨm was maintained with no decrease in O2 consumption during matrix Ca2+ release, consistent with transient mPTP openings. Calibration was obtained using alamethicin (Ala) to dissipate ΔΨm fully and release all matrix Ca2+.

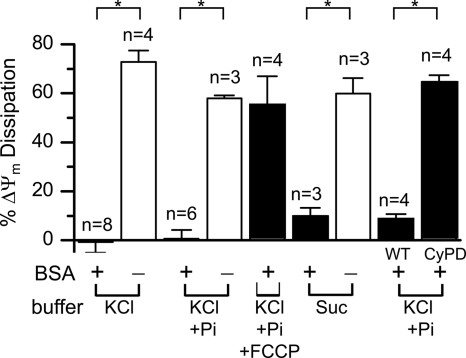

However, if BSA was included in the buffer to mimic cytoplasmic proteins that normally bind fatty acids and therefore decrease IMM proton leak associated with fatty acid cycling (19), matrix Ca2+ release occurred without significant dissipation in the average ΔΨm of the mitochondrial population (Fig. 1B). Each Ca2+ pulse caused a transient elevation of extramitochondrial Ca2+ (measured with a Ca2+-sensitive electrode), which was taken up by the mitochondria in association with a transient small ΔΨm depolarization, apparent as small oscillations in the TMRM tracing (which, for larger Ca2+ pulses, were correspondingly larger). However, in the presence of BSA, the average ΔΨm then re-equilibrated. At a critical Ca2+ load, mitochondria began to release their accumulated matrix Ca2+, but the average ΔΨm of the mitochondrial population as a whole remained polarized. Unlike the results shown in Fig. 1A, in which O2 consumption decreased after matrix Ca2+ release, O2 consumption remained high after matrix Ca2+ release in the presence of BSA (indicated by the stable non-zero level reflecting O2 consumption in balance with O2 diffusion into the open cuvette), consistent with adequate matrix NAD/NADH. These findings were confirmed when extramitochondrial free Ca2+ was monitored using Calcium Green-5N salt instead of the Ca2+-sensitive electrode, and ΔΨm was measured with a tetraphenylphosphonium electrode (supplemental Fig. S1). Fig. 2 summarizes the changes in ΔΨm after matrix Ca2+ release in the absence and presence of BSA and also shows that similar findings were obtained with exogenous Pi present, although a significantly larger total Ca2+ load was required to release matrix Ca2+ (204 ± 20 nmol/mg of protein (n = 6) with Pi and 66 ± 5 nmol/mg of protein (n = 9) without Pi; p < 0.01). The higher Ca2+ load is consistent with the known ability of Pi to enhance matrix Ca2+ buffering. Fig. 2 also shows that similar findings were obtained when mitochondria were suspended in sucrose buffer in place of KCl buffer. In this case, the Ca2+ loads required to induce matrix Ca2+ release averaged 187 ± 22 nmol/mg of protein with Pi (n = 4) and 108 ± 26 nmol/mg of protein without Pi (n = 4; p < 0.01).

FIGURE 2.

Bar graph summary of percent ΔΨm dissipation with or without BSA (1 mg/ml) measured at near-peak matrix Ca2+ release when isolated rabbit cardiac mitochondria were incubated in KCl buffer, KCl + Pi (2. 5 mm) buffer with and without FCCP (15–25 nm), and sucrose (250 mm) buffer. White and black bars indicate that BSA was absent (−) or present (+), respectively. The rightmost bars compare cardiac mitochondria isolated from WT and CyPD KO mice, respectively, incubated in KCl buffer + Pi (2.5 mm) with BSA present. Suc, sucrose buffer. *, p < 0.05.

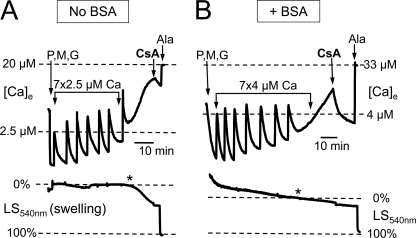

In both the absence (Fig. 3A) and presence (Fig. 3B) of BSA, matrix Ca2+ release was reversed by CsA if added early, consistent with matrix Ca2+ release being mediated by mPTP openings. To investigate the role of mPTP further, we also studied cardiac mitochondria isolated from CyPD KO (Ppif −/−) mice, in which mPTP formation is defective but not abolished (8, 12). Cardiac mitochondria from wild-type mice maintained ΔΨm during matrix Ca2+ release when BSA was present (averaging 99 ± 13 nmol/mg of protein in KCl buffer with Pi, n = 6). In contrast, mitochondria from CyPD KO mitochondria tolerated higher Ca2+ loads before matrix Ca2+ release occurred (averaging 280 ± 24 nmol/mg of protein in KCl buffer with Pi, n = 4), as reported previously (8), but developed ΔΨm dissipation coincident with matrix Ca2+ release (Fig. 2). CsA did not reverse matrix Ca2+ release or restore ΔΨm. Thus, CyPD KO mitochondria were unable to maintain ΔΨm during matrix Ca2+ release in the presence of BSA, consistent with a defect in transient mPTP opening.

FIGURE 3.

Matrix Ca2+ release is inhibited by CsA, and transient mPTP openings occur in a low conductance mode when BSA is present. Mitochondria were added to 250 mm sucrose buffer containing 0.2 mm Pi at the beginning of the trace, followed by Complex I substrates pyruvate (P), malate (M), and glutamate (G) (3.5 mm each), while simultaneously recording extramitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca]e; upper) and light scattering at 540 nm (LS450nm; lower) to monitor matrix swelling (downward deflection = increased swelling). A, in the absence of BSA, Ca2+ pulses (2.5 μm each) were added until matrix Ca2+ release occurred (asterisk), at which time the matrix swelling rate also increased markedly. CsA caused Ca2+ reuptake and immediately stopped further swelling. B, with 1 mg/ml BSA present, a larger amount of Ca2+ was required to induce matrix Ca2+ release (asterisk), which was reversed by addition of CsA. The swelling rate did not change appreciably before or after CsA addition, indicating that the IMM remained impermeant to sucrose. In both cases, alamethicin (Ala; 10 μg) was added at the end for calibration purposes to show maximum Ca2+ release and swelling.

Why is BSA required to observe released matrix Ca2+ without detectable dissipation of the average ΔΨm? We hypothesized that when a mPTP stochastically opens and immediately dissipates ΔΨm, it will close stochastically while the mitochondria are still depolarized. The mitochondria can then regenerate ΔΨm, which they can do much more rapidly if the IMM proton leak is low due to BSA chelating fatty acids. Because mPTP open probability is voltage-dependent, the probability that the mPTP will reopen remains high as long as the ΔΨm is depolarized but becomes much lower once ΔΨm has been re-established. Thus, the time to repolarize ΔΨm is a critical determinant of whether the mPTP will reopen or not. We postulated that in the absence of BSA, the longer time required to repolarize ΔΨm due to the greater IMM proton leakiness makes the closed mPTP more likely to reopen, creating a positive feedback in which loss of essential matrix metabolites such as NAD/NADH further impedes the ability of respiration to restore ΔΨm, such that mPTP opening becomes long-lasting and eventually irreversible. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of increasing the IMM proton leak when BSA was present by adding a low concentration of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP). With BSA present, 15–25 nm FCCP caused only a mild ΔΨm dissipation before Ca2+ addition but eliminated the ability of mitochondria to maintain ΔΨm (Fig. 2) and robust O2 consumption during matrix Ca2+ release (supplemental Fig. S2), consistent with long-lasting mPTP opening. Thus, FCCP abrogated the effects of BSA.

Molecular Weight Cutoff of Transient mPTP Openings

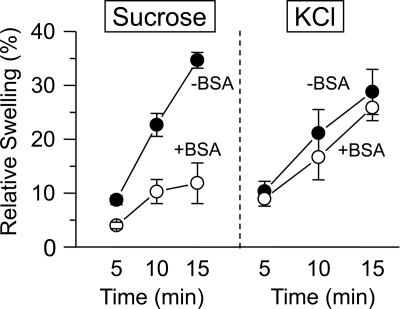

If mitochondria can utilize transient mPTP openings to flush matrix Ca2+ rapidly, they must retain key matrix metabolites such as NADH during the brief time when an mPTP is open to have sufficient respiratory power to repolarize once the mPTP closes. However, the free diffusion of NADH in water is only ∼2-fold slower compared with Ca2+, implying that another factor must be present to restrict NADH diffusion relative to Ca2+ diffusion through the open mPTP. Possible explanations are that transient mPTP openings are too brief or occur in a low conductance mode that permits Ca2+ efflux but restricts efflux of larger molecules such as NADH (9–11, 20, 21). To investigate this possibility, we compared the extent of matrix swelling during Ca2+ loading in the absence and presence of BSA (Figs. 3 and 4). mPTP opening causes matrix swelling due to unrestricted entry of osmotically active molecules into the matrix when the pore is open. When mitochondria were suspended in KCl buffer, swelling after the onset of matrix Ca2+ release was comparable without or with BSA present (Fig. 4). In sucrose buffer without BSA, matrix swelling was also similarly large and terminated once CsA was added (Fig. 3A). However, with BSA present in sucrose buffer, matrix swelling was markedly blunted (Fig. 3B), indicating that the IMM remained impermeant to sucrose (Mr 340) during matrix Ca2+ release. This indicates that with BSA present, mPTP openings allowed small ions such as potassium and calcium with Mr <340 to pass freely through the pore but were either too brief or exhibited a reduced conductance state that restricted permeation of larger molecules such as sucrose (and NAD/NADH). In contrast, in the absence of BSA, the similar magnitude of swelling as in KCl buffer implies that sucrose was able to permeate the pore, consistent with classic large conductance mPTP openings, whose molecular weight cutoff has been estimated at 1500 (22).

FIGURE 4.

Summary of effects of BSA on matrix swelling in sucrose versus KCl buffer. Left, using the Ca2+-loading protocol in Fig. 3, mitochondrial swelling in sucrose buffer with 0.2 mm Pi, recorded from the onset of matrix Ca2+ release (0%), relative to maximal swelling after addition of alamethicin (100%) was much greater without BSA (●) than with BSA (○). Right, comparison with KCl buffer with 0.2 mm Pi in the presence and absence of BSA. Values are the mean ± S.D. of three to five preparations.

ROS Production Is Increased during Matrix Ca2+ Release via Transient mPTP Openings

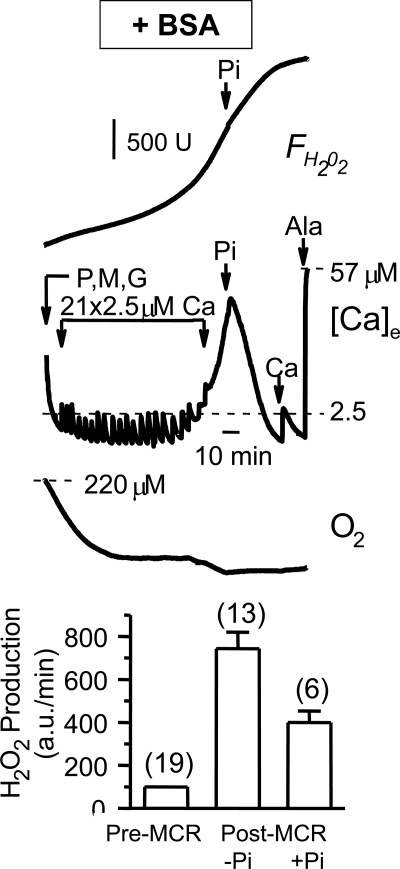

Transient mPTP openings have been shown to increase mitochondrial ROS production (23) by inducing “superoxide flashes” (24). Consistent with these observations, we found that in the presence of BSA, matrix Ca2+ release with ΔΨm maintained was accompanied by a marked increase in mitochondrial ROS generation, detected using the H2O2 indicator Amplex Red (Fig. 5). Note that in Fig. 5, O2 consumption transiently increased during matrix Ca2+ release and then remained stable, indicating that respiratory chain activity was not compromised by loss of essential matrix metabolites such as NADH during transient mPTP openings. Also, subsequent addition of Pi stimulated reuptake of Ca2+, which can occur only if mPTP can close to regenerate ΔΨm. The ability of Pi to reverse matrix Ca2+ efflux under these conditions was also confirmed using the extramitochondrial Ca2+-sensitive dye Calcium Green-5N in place of the Ca2+-sensitive electrode (supplemental Fig. S3). Finally, increased H2O2 production during matrix Ca2+ release was also observed when Pi was present prior to the onset of Ca2+ loading (Fig. 5, lower panel).

FIGURE 5.

Increased ROS production during matrix Ca2+ release. Upper panel, traces of Amplex Red (resorufin) fluorescence measuring mitochondrial H2O2 production (FH2O2; upper), O2 consumption (lower), and extramitochondrial free [Ca2+] ([Ca]e; middle) during addition of Ca2+ pulses to induce matrix Ca2+ release in the absence of Pi as in Fig. 1A. O2 consumption and H2O2 production rates increased markedly coincident with matrix Ca2+ release and slowed after addition of Pi (2.5 mm). Note that mitochondrial Ca2+ reuptake promoted by Pi is possible to explain only if mPTP openings during matrix Ca2+ release were transient. Ala, alamethicin; P, pyruvate; M, malate; G, glutamate. B, bar graph summarizing the increase in H2O2 production rate after the onset of matrix Ca2+ release (MCR) without (−) or with (+) 2.5 mm Pi present from the start. The increase in H2O2 production rate was measured as the percent increase in the slope of the FH2O2 curve after matrix Ca2+ release (as in A). Values are the mean ± S.D. for the number of preparations indicated, reflecting the slope of FH2O2. a.u., arbitrary units.

DISCUSSION

Transient mPTP openings have been proposed to serve as a Ca2+ release mechanism by which mitochondria avoid matrix Ca2+ overload (9–11, 20, 21). We reasoned that this mechanism could explain our experimental finding of matrix Ca2+ release without dissipation of the average ΔΨm of the mitochondrial population if (i) transient mPTP openings occur asynchronously in the mitochondrial population, and (ii) the release of accumulated matrix Ca2+ during a transient mPTP opening is rapid relative to the rate of Ca2+ reuptake into the matrix. For example, if an mPTP opening of 100 ms were sufficient to re-equilibrate matrix-free Ca2+, but subsequent re-accumulation of matrix Ca2+ reuptake took 10 s (consistent with the half-time of Ca2+ uptake after a Ca2+ pulse in Fig. 1B), then the 100-to-1 difference between the rates of release and reuptake would require each mitochondrion to be depolarized only 1% of the time to flush Ca2+ from the matrix. Thus, as long as transient mPTP openings occur asynchronously due to their stochastic properties, only 1% of the mitochondria in the cuvette would be depolarized at any given moment, a fraction too small to be detected using TMRM (i.e. if ΔΨm remained at −180 mV in 99% of mitochondria, the 1% depolarized fraction would decrease the average ΔΨm by 1% to −178 mV). Moreover, because increased matrix Ca2+ stimulates respiration, promoting ΔΨm hyperpolarization, then if 99% of mitochondria modestly increased ΔΨm (e.g. from −180 to −190 mV), the average ΔΨm of the population would appear to hyperpolarize (e.g. −190 mV × 0.99 = −188 mV), completely obscuring the 1% of completely depolarized mitochondria with open mPTP. (The feasibility of this scenario was substantiated quantitatively in a mitochondrial model incorporating transient mPTP openings (supplemental Fig. S4).)

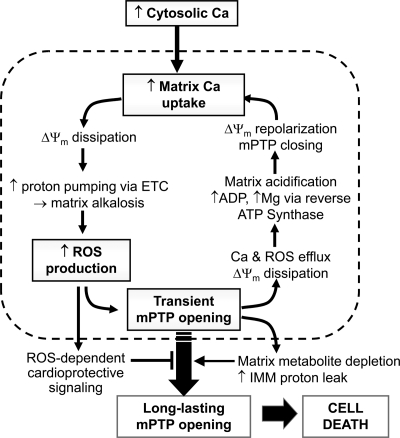

Fig. 6 summarizes schematically the proposed interplay between transient and long-lasting mPTP openings. When isolated mitochondria are subjected to Ca2+ loading under conditions in which IMM proton leak is allowed to increase (presumably caused by increased fatty acid cycling (19)), matrix Ca2+ release occurs concurrently with ΔΨm dissipation and swelling due to triggering of long-lasting mPTP openings. This is the basis of the classic assay for the Ca2+-induced mitochondrial permeability transition. However, when IMM proton leak during Ca2+ loading is minimized by including BSA to bind fatty acids, cardiac mitochondria are able to utilize transient mPTP openings to release accumulated matrix Ca2+ and then repolarize rapidly enough after the mPTP stochastically closes to inhibit subsequent mPTP reopening because mPTP open probability is suppressed by negative ΔΨm. If the repolarization rate is slow due to proton leak (i.e. without BSA or with BSA + a low FCCP concentration), then the mPTP reopens, further compromising respiratory power. Thus, the response depends on the ability of the respiratory chain to balance proton influx with proton pumping, which is possible when IMM proton leak is low. Because the reuptake of Ca2+ into the matrix via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter is a slow process relative to mPTP-mediated Ca2+ release from the matrix, a mitochondrion can tolerate markedly elevated extramitochondrial free Ca2+ levels by depolarizing intermittently to flush Ca2+ while remaining polarized >99% of the time. Because mitochondria in situ are in a highly proteinaceous environment in which endogenous cytoplasmic proteins bind fatty acids similar to BSA, this mechanism may be physiologically important in allowing cardiac mitochondria to avoid matrix Ca2+ overload and maintain ATP production in the face of cyclical elevations in cytoplasmic free [Ca2+] to the micromolar level in the beating heart. This may also explain why large conductance mPTP opening is difficult to induce by Ca2+ loading alone in intact cardiac myocytes unless other factors such as high ROS levels are also present (25).

FIGURE 6.

Schema of matrix Ca2+ regulation by transient mPTP openings. As long as mitochondria have sufficient electron transport/proton pumping power, they can use transient mPTP openings to flush matrix Ca2+ and then quickly repolarize while only slowly re-accumulating matrix Ca2+, as outlined by the cycle inside the dashed box. This allows a population of asynchronously cycling mitochondria to tolerate markedly elevated extramitochondrial free Ca2+ levels without collectively depolarizing, whereas increased ROS production due to transient mPTP opening engages cardioprotective signaling. Eventually, however, depletion of critical metabolites from the matrix, together with a gradual decrease in respiratory chain activity, compromises the ability of mitochondria to repolarize quickly after transient mPTP openings, promoting the transition to long-lasting mPTP opening and its destructive consequences. See “Discussion” for further details. ETC, electron transport chain.

Given that cardiac mitochondria face varying cytoplasmic free [Ca2+] under physiological and pathological conditions, the importance of a mechanism to protect against excessive matrix Ca2+ overload and thereby avoid long-lasting mPTP opening and its destructive consequences is obvious. When ΔΨm is fully polarized, the energetic cost of removing excess Ca2+ from the matrix against a −180 mV driving force is huge, and both sodium-calcium exchange and hydrogen-calcium exchange are kinetically slower than Ca2+ uptake via the Ca2+ uniporter (26). Complete ΔΨm dissipation by a transient mPTP opening allows accumulated matrix Ca2+ to flow rapidly out of the matrix down its concentration gradient and equilibrate with cytoplasmic free [Ca2+] (27) at a much faster rate than possible via sodium-calcium or hydrogen-calcium exchange. As long as the mPTP reliably closes again (promoted by reduction of matrix-free [Ca2+], proton influx acidifying the matrix pH, and magnesium released during ATP hydrolysis (22)) and respiratory chain activity is not compromised by loss of critical matrix metabolites such as NADH, the mitochondrion can rapidly regenerate ΔΨm and return to its normal function of synthesizing ATP. The average ΔΨm of the mitochondrial population was sometimes even observed to hyperpolarize modestly during matrix Ca2+ release, which we speculate may have resulted from the combination of Ca2+-stimulated respiration and matrix acidification accompanying transient mPTP opening, which converts the chemical pH gradient into ΔΨm.

For the mechanism in Fig. 6 to work, transient mPTP openings must promote rapid Ca2+ efflux from the matrix without allowing loss of key metabolites such as NAD/NADH, which would compromise the ability of electron transport to regenerate ΔΨm rapidly once the pore closed. One possibility is that the transient openings occur in a low conductance mode, as reported previously (9, 20, 21), perhaps corresponding to a subconductance state of the fully open pore as recorded in mitoplasts (28). This possibility is consistent with the results using sucrose buffer (Figs. 3 and 4) showing that mitochondrial swelling during matrix Ca2+ release was minimal with BSA present compared with no BSA or with KCl buffer. This could be interpreted to indicate that molecules with Mr 340 or greater (including both sucrose and NAD/NADH) remain impermeant to the IMM during transient mPTP openings. On the other hand, it has been shown previously that calcein (Mr 623) can be released by transient mPTP openings without any detectable loss of ΔΨm (29), suggesting that calcein and NAD/NADH may have different permeation properties despite their similar molecular weights. Thus, it is possible that transient openings occur in the full conductance mode, but other factors, such as the brevity of openings or binding properties in the matrix, restrict the diffusion of specific molecules such as NAD/NADH (Mr ∼663) and sucrose relative to calcein and small ions like calcium and potassium. With long-lasting mPTP openings sufficient to depolarize the average ΔΨm of the mitochondrial population, however, NADH, like sucrose, freely permeated the pore, as shown by the increase in O2 consumption upon NADH addition in Fig. 1A. It seems unlikely that matrix Ca2+ efflux could occur via the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter instead of mPTP because the available evidence suggests that the uniporter is an inwardly rectifying Ca2+ channel with very small unitary conductance compared with the mPTP (30, 31). In addition, the rate of matrix Ca2+ uptake via the uniporter had a half-time exceeding 10 s (Fig. 1), yet matrix Ca2+ efflux through the uniporter (which is slower than influx due to the inward rectification) would have to occur much more rapidly during the brief (<1 s) depolarization while the mPTP is open.

We speculate that the transition from transient to long-lasting mPTP openings is gradual, eventually leading to depletion of key metabolites for electron transport. This, together with increased IMM leak, could be a critical factor converting transient openings to long-lasting openings with their destructive consequences (Fig. 6). Irrespective of the precise mechanism regulating pore permeation, for mPTP openings to remain transient requires that mitochondria have a well functioning respiratory chain with low IMM proton leak. Although we speculate that the major role of BSA is to prevent IMM proton leakiness by chelating fatty acids (mimicking cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins normally present in situ), we cannot absolutely exclude the possibility that BSA also has direct effects on mitochondrial Ca2+-handling proteins or the mPTP.

Implications for Cardioprotection

The scenario outlined in Fig. 6 could explain the accelerated development of heart failure in CyPD KO mice exposed to transaortic constriction or cross-bred with cardiomyopathy-susceptible mice overexpressing Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIδc, consistent with the impaired mitochondrial Ca2+ handling observed in these animals (12) due to defective transient mPTP openings. In addition, this scenario may account for several observations relevant to cardioprotection by ischemic and pharmacologic PC. The induction of cardioprotection is known to be dependent on signaling cascades triggered by ROS production during the PC period (4, 5). Pre-conditioning I/R episodes are likely to expose mitochondria to modest Ca2+ overload conditions, which, if sufficient to trigger transient mPTP openings, would secondarily increase ROS production by generating superoxide flashes (23, 24), as observed in Fig. 5. This ROS generation may synergistically summate with other sources of mitochondrial ROS production, e.g. from activation of mitochondrial KATP channels, to initiate ROS-dependent cardioprotective signaling. A requirement for multiple sources to generate adequate ROS to engage cardioprotective signaling would explain why ROS scavengers, CsA, or mitochondrial KATP antagonists are all individually effective at blocking cardioprotection when administered during PC episodes (4, 5). The specific source generating ROS seems to be less important than the absolute amount of ROS because exogenously applied ROS are also effective at triggering cardioprotective signaling (4, 5).

The activation of this protective role of transient mPTP openings is, however, a two-edged sword. To tolerate extramitochondrial free [Ca2+] >5 μm without depolarizing, isolated cardiac mitochondria had to have well functioning electron transport with efficient proton pumping coupled to a low level of IMM proton leak. If electron transport/proton pumping was compromised and/or the IMM was leaky, matrix Ca2+ release was always accompanied by significant ΔΨm dissipation. As the duration of ischemia is prolonged, the progressive accumulation of fatty acids (32) increases IMM leakiness, and electron transport power weakens. Under these conditions, the likelihood increases that transient mPTP openings will be converted into long-lasting full conductance openings, leading to irreversible mitochondrial injury.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be recognized. First, our studies were performed in isolated mitochondria, in which the physiological environment of mitochondria is perturbed, and normal signaling may be partially or completely disrupted. BSA may have different properties than the fatty acid-binding proteins normally present in the cytoplasm or could regulate mitochondrial Ca2+-cycling proteins or mPTP directly. However, the BSA concentration used in our study was much lower than that used in other studies to mimic the oncotic pressure of the cytoplasm (33), and the rate of Ca2+ uptake during the initial Ca2+ pulses was similar in the presence and absence of BSA (e.g. Fig. 1). We confirmed that BSA did not quench TMRM fluorescence or bind tetraphenylphosphonium in a manner that could artifactually explain the maintenance of ΔΨm during Ca2+ loading. We inferred transient mPTP openings but could not directly observe them in individual mitochondria because only the average ΔΨm of the total mitochondrial population can be measured in a spectrofluorometer cuvette. However, the plausibility of the proposed mechanism is supported by theoretical considerations (22) and reproduced quantitatively by the mathematical modeling (see supplemental “Experimental Procedures”). In future studies, it may be possible to observe transient mPTP openings directly by imaging single isolated (34) or in situ (24) mitochondria. Although the open times may be too short to detect with voltage indicators such as TMRM, our findings predict that transient mPTP openings in single mitochondria should be accompanied by rapid matrix Ca2+ depletion, and recover slowly over a time course of minutes and be suppressed by CsA. On the other hand, if transient mPTP openings occur as infrequently as once every 25 min, as predicted in the quantitative model, they may be difficult to detect.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Henry Honda, Scott John, and Bernard Ribalet for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 HL080111, R01 HL071870, and R01 HL095663 from NHLBI. This work was also supported by the Laubisch and Kawata Endowments.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Figs. S1–S4, and additional references.

- mPTP

- mitochondrial permeability transition pore(s)

- IMM

- inner mitochondrial membrane

- PC

- pre- and post-conditioning

- CsA

- cyclosporine A

- I/R

- ischemia/reperfusion

- CyPD

- cyclophilin D

- KO

- knock-out

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone.

REFERENCES

- 1. Halestrap A. P., Kerr P. M., Javadov S., Woodfield K. Y. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1366, 79–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. (1995) Biochem. J. 307, 93–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiss J. N., Korge P., Honda H. M., Ping P. (2003) Circ. Res. 93, 292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy E., Steenbergen C. (2007) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 69, 51–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Downey J. M., Davis A. M., Cohen M. V. (2007) Heart Fail. Rev. 12, 181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hausenloy D. J., Ong S. B., Yellon D. M. (2009) Basic Res. Cardiol. 104, 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. (1993) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 25, 1461–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baines C. P., Kaiser R. A., Purcell N. H., Blair N. S., Osinska H., Hambleton M. A., Brunskill E. W., Sayen M. R., Gottlieb R. A., Dorn G. W., Robbins J., Molkentin J. D. (2005) Nature 434, 658–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ichas F., Mazat J. P. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1366, 33–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hüser J., Blatter L. A. (1999) Biochem. J. 343, 311–317 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jacobson J., Duchen M. R. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 1175–1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elrod J. W., Wong R., Mishra S., Vagnozzi R. J., Sakthievel B., Goonasekera S. A., Karch J., Gabel S., Farber J., Force T., Brown J. H., Murphy E., Molkentin J. D. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3680–3687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakayama H., Chen X., Baines C. P., Klevitsky R., Zhang X., Zhang H., Jaleel N., Chua B. H., Hewett T. E., Robbins J., Houser S. R., Molkentin J. D. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2431–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hausenloy D., Wynne A., Duchen M., Yellon D. (2004) Circulation 109, 1714–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saotome M., Katoh H., Yaguchi Y., Tanaka T., Urushida T., Satoh H., Hayashi H. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 269, H1125–H1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Penna C., Mancardi D., Rastaldo R., Pagliaro P. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 781–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korge P., Honda H. M., Weiss J. N. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C517–C526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korge P., Ping P., Weiss J. N. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 873–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Skulachev V. P. (1999) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 31, 431–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Novgorodov S. A., Gudz T. I. (1996) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ichas F., Jouaville L. S., Mazat J. P. (1997) Cell 89, 1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernardi P. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 1127–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zorov D. B., Filburn C. R., Klotz L. O., Zweier J. L., Sollott S. J. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 1001–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang W., Fang H., Groom L., Cheng A., Zhang W., Liu J., Wang X., Li K., Han P., Zheng M., Yin J., Wang W., Mattson M. P., Kao J. P., Lakatta E. G., Sheu S. S., Ouyang K., Chen J., Dirksen R. T., Cheng H. (2008) Cell 134, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Juhaszova M., Wang S., Zorov D. B., Nuss H. B., Gleichmann M., Mattson M. P., Sollott S. J. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1123, 197–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andrienko T. N., Picht E., Bers D. M. (2009) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 1027–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bernardi P., Petronilli V. (1996) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petronilli V., Szabò I., Zoratti M. (1989) FEBS Lett. 259, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petronilli V., Miotto G., Canton M., Brini M., Colonna R., Bernardi P., Di Lisa F. (1999) Biophys. J. 76, 725–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kirichok Y., Krapivinsky G., Clapham D. E. (2004) Nature 427, 360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Stefani D., Raffaello A., Teardo E., Szabo I., Rizzuto R. (2011) Nature 476, 336–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DaTorre S. D., Creer M. H., Pogwizd S. M., Corr P. B. (1991) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 23, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liobikas J., Kopustinskiene D. M., Toleikis A. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1505, 220–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hüser J., Rechenmacher C. E., Blatter L. A. (1998) Biophys. J. 74, 2129–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.