Abstract

Mast cells, critical mediators of inflammation and anaphylaxis, are poised as one of the first lines of defense against external assault. Mast cells release several classes of preformed and de novo synthesized mediators. Cross-linking of the high-affinity Fc∊RI results in degranulation and the release of preformed, proinflammatory mediators including histamine and serotonin. We previously demonstrated that mast cell activation by Listeria monocytogenes requires the α2β1 integrin for rapid IL-6 secretion both in vivo and in vitro. However, the mechanism of IL-6 release is unknown. Here, we demonstrate the Listeria- and α2β1 integrin-mediated mast cell release of preformed IL-6 without the concomitant release of histamine or β-hexosaminidase. α2β1 integrin-dependent mast cell activation and IL-6 release is calcium independent. In contrast, IgE cross-linking-mediated degranulation is calcium dependent and does not result in IL-6 release, demonstrating that distinct stimuli result in the release of specific mediator pools. These studies demonstrate that IL-6 is presynthesized and stored in connective tissue mast cells and can be released from mast cells in response to distinct, α2β1 integrin-dependent stimulation, providing the host with a specific innate immune response without stimulating an allergic reaction.

Copyright © 2011 S. Karger AG, Basel

Key Words: Adhesion molecules, Cytokines, Host defense, Integrin, Mast cell

Introduction

The α2β1 integrin serves as a receptor for a number of matrix and nonmatrix ligands, including collagens and a family of immune modulatory ligands, C1q and the collectin family of proteins. The integrin plays an important role in the innate immune response to infectious agents [1,2,3,4]. Initially, we demonstrated that α2β1 integrin expression by peritoneal mast cells (PMCs) is required for early, acute inflammatory responses to Listeria monocytogenes [5]. In earlier studies we demonstrated that the α2β1 integrin is expressed at high levels on PMCs but not on bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) and recognizes the C1q complement protein in an immune complex containing Listeria [1,5]. We recently described a novel pathway for mast cell activation mediated by cross talk between the α2β1 integrin and the hepatocyte growth factor/c-met [6]. The engagement of both receptors was required for mast cell activation, rapid interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion in vitro and in vivo, and neutrophil recruitment in vivo.

Although mast cells are primarily known for their function as mediators of IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity, they are also appreciated as versatile cells of the immune system, contributing to the innate and adaptive defense against external insults as well as to allergic responses [1,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The best characterized pathway for mast cell secretion is the compound degranulation that occurs following cross-linking of the high-affinity Fc∊RI with IgE antibodies and specific antigens [14]. IgE cross-linking leads to the calcium-dependent release of preformed mediators, including histamine and serotonin [8,10,15]. IgE cross-linking initiates a sequence of downstream signals that lead to cytoskeletal reorganization, granule-granule fusion, granule docking with the plasma membrane, and the release of soluble mediators [16,17]. A number of recent studies have elucidated the complexity of mast cell secretion and the selective release of granules [18]. Puri and Roche [18] demonstrated that BMMCs possess 2 distinct secretory granules, i.e. one that contains histamine and β-hexosaminidase and a second that contains serotonin and cathepsin D. Although Fc∊RI cross-linking results in the release of both granule subsets, the secretion is mediated by distinct SNARE isoforms. Here, we demonstrate that mast cells can be activated by L. monocytogenes and secrete IL-6 in an α2β1 integrin- and c-met-dependent, but IgE-independent, manner. The selective release of IL-6 and other cytokines selectively activates innate immunity without stimulation of the detrimental consequences associated with allergy.

To determine the mechanism of α2β1 integrin- and c-met-dependent IL-6 secretion, we compared the response of PMC activation resulting from exposure to Listeria opsonized by an immune complex to that of PMCs stimulated by IgE cross-linking. IL-6 was released from PMCs following stimulation by Listeria plus an immune complex at 1 h but not by IgE binding to a multivalent antigen within the same time frame. Moreover, in contrast to the classic response of PMC to IgE cross-linking, IL-6 secretion was Ca independent, occurred without the release of serotonin or histamine, and did not require de novo transcriptional or translational synthesis of IL-6. Our data demonstrate that pathways leading to PMC activation in response to IgE cross-linking are distinct from pathways leading to the secretion of preformed IL-6 secretion in response to Listeria, thus providing the host with the ability to selectively activate the innate immune system.

Materials and Methods

Mast Cell Preparations

Animals were housed in pathogen-free conditions at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in compliance with institutional IACUC regulations. α2 integrin subunit-deficient (α2–/–) mice and their wild-type (WT) littermate controls on a C57BL/6 × 129/Sv background were used at 6–20 weeks of age. PMCs were isolated from residential peritoneal exudates using Percoll gradient centrifugation (∼85% purity) [1]. Fetal skin-derived mast cells (FSMC) were generated as described previously [19]. Single cell suspensions of day-16 fetal trunk skin were generated by incubation in 0.25% trypsin in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution for 20 min at 37°C. After erythrocyte lysis with lysing buffer (0.15 mM NH4Cl, 1.0 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM Na2EDTA), cells were washed and seeded at 2 × 104 cells/ml in FSMC media [RPMI1640, 10% FBS,10 mM NEAA, 10 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.01% penicillin-streptomycin, 25 mM HEPES buffer, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 ng/ml IL-3 and SCF (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, N.J., USA)]. After 10–14 days, nonadherent cells were assessed for the expression of c-kit and expression of the α2β1 integrin. Cultures of FSMCs were used if more than 85% of the WT cells coexpressed c-kit and the α2β1 integrin. Expression of c-kit or the α2β1 integrin was carried out by flow cytometric analysis using the following antibodies (all from BD Biosciences, San Diego, Calif., USA): FITC-anti-CD117 (c-kit; 2B8) and PE-anti-CD49b (integrin subunit; HMα2).

In vitro Activation Assays

For in vitro mast cell activation by Listeria, purified PMCs (5 × 104 cells/well) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with a washed suspension of Listeria (1 × 107 organisms) and with rabbit anti-Listeria antibody and 50% serum. To determine the activation by IgE cross-linking, cells (5 × 104) were preloaded for 18 h with anti-DNP IgE (1 μg/ml, SPE-7; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., USA) in Tyrodes buffer (137 mM NaCl/11.9 mM NaHCO3/0.4 mM Na2HPO4/2.7 mM KCl/1.1 mM MgCl2/5.6 mM glucose, pH 7.3). The sensitized cells were washed twice in Tyrodes buffer and stimulated with 100 ng/ml DNP-HSA (Sigma-Aldrich) for the indicated time points. As noted, FSMCs were pretreated with actinomycin D (2 μg/ml) or cycloheximide (20 μM) for 15 min or with brefeldin A (BFA; 1 μg/ml), monensin (1 μM), or BAPTA (2.5 μM) for 30 min (all reagents from Sigma-Aldrich) prior to stimulation.

The concentration of IL-6 and IL1β (BD Biosciences) and histamine and serotonin (both from Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, Mass., USA) in cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA as per the manufacturer's instructions. The degree of degranulation was determined by measuring the release of β-hexosaminidase. The enzymatic activity of β-hexosaminidase in supernatants and cell pellets solubilized with 1% Triton X-100 in Tyrode's buffer was measured with p-nitrophenyl N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 4.5) for 60 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2 M glycine (pH 10.7). The release of the product, 4-p-nitrophenol, was detected by absorbance at 405 nm. The extent of degranulation was calculated by dividing the 4-p-nitrophenol absorbance in the supernatant by the sum of the absorbance in the supernatant and detergent-solubilized cell pellet. Calcium mobilization was determined as per the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif., USA).

Mast Cell Fractionation

Fractionation of mast cells to isolate mast cell granules was performed using a washed preparation of 1 × 107 FSMCs. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and submitted to 3 freeze/thaw cycles. The homogenate was sonicated and centrifuged at 1,850 g for 10 min to pellet nuclei [20]. The postnuclear supernatant (PNS) was separated on a 2-layer Percoll gradient of 10× sucrose and water with gradient densities of 1.05 and 1.12 (2 ml/layer). The gradient was layered in 5-ml polycarbonate ultracentrifugation tubes (Beckman, Fullerton, Calif., USA). After applying the PNS on top of the gradient, the samples were spun at 190,000 g for 50 min in a Sorvall Discovery 90SE ultracentrifuge using the AH650 rotor. Samples of 200 μl were collected starting from the top of the gradient, and the concentration of IL-6, histamine, and serotonin in each fraction was determined by ELISA.

Immunofluorescence

FSMCs were incubated with 200 μM 5-HT (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h, washed with PBS, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and washed and permeabilized with 0.05% Tween-20/PBS for 15 min. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and blocked with 3% horse serum/PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Primary rabbit anti-mouse IL-6 antibody (US Biologicals, Swampscott, Mass., USA) and primary murine anti-5-HT serotonin antibody were added overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed and treated with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 633 (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, Calif., USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were mounted and imaged with an LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Germany) and the images were processed using LSM ImageBrowser (Carl Zeiss Microimaging) software.

Results

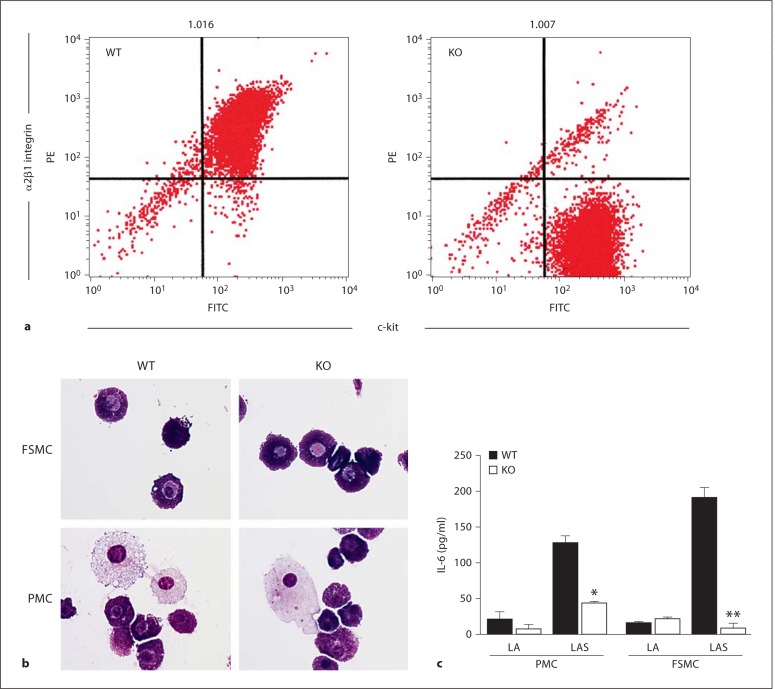

To define the molecular mechanisms leading to α2β1 integrin- and c-met-dependent PMC activation, we compared the time course, calcium requirement, and mediator release following either mast cell stimulation by Listeria plus an immune complex or IgE cross-linking. α2β1 integrin- and c-met-dependent activation is unique to PMC since BMMCs are more immature and fail to express the α2β1 integrin [19]. Mechanistic studies of mast cell activation required larger numbers of cells than mast cell purification from peritoneal fluid provided. Therefore, we generated connective tissue mast cells from murine fetal skin as previously described by Yamada et al. [19]. FSMCs had been shown to closely resemble the phenotype of connective tissue mast cells, including increased histamine content, the presence of heparin, degranulation in response to compound 48/80, and expression of high levels of the α2β1 integrin. The α2β1 integrin was expressed at a similar intensity in WT, but not α2-null, FSMCs, as expected from previous studies by our group and others (fig. 1a and as previously reported) [1,19]. Therefore, the morphology and response to Listeria of FSMCs was compared to that of purified PMCs. FSMCs appeared morphologically identical to PMCs (fig. 1b). Since all of our previous work was carried out using PMCs, we compared the response of WT and α2-null PMCs to that of WT and α2-null FSMCs following Listeria opsonized with an immune complex (fig. 1c). Both FSMCs and PMCs from WT mice responded with the release of IL-6 in an α2β1 integrin-dependent manner (fig. 1c). Both FSMCs and PMCs from α2-null mice failed to secrete IL-6 in response to Listeria, demonstrating that PMCs and FSMCs behave in a similar manner (fig. 1c). Therefore, FSMCs were used throughout this study.

Fig. 1.

Similarities between FSMCs and PMCs. a Expression of the α2-integrin subunit (CD49b) and c-kit was determined by flow cytometric analysis of FSMCs. More than 85% of WT FSMCs coexpressed c-kit and the α2β1 integrin. α2-null (KO) FSMCs expressed c-kit but not the α2β1 integrin. b FSMCs and PMCs are morphologically similar when examined using Wright-Giemsa staining. c WT but not α2-null (KO) FSMCs and PMCs secreted IL-6 in response to Listeria. Both WT and α2-null FSMCs and PMCs were stimulated with Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody (LA) or Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum (LAS) for 1 h at 37°C. Cell-free supernatants were analyzed for IL-6 by ELISA. IL-6 concentrations are expressed as means ± SEM. All data are representative of at least 3 separate experiments. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

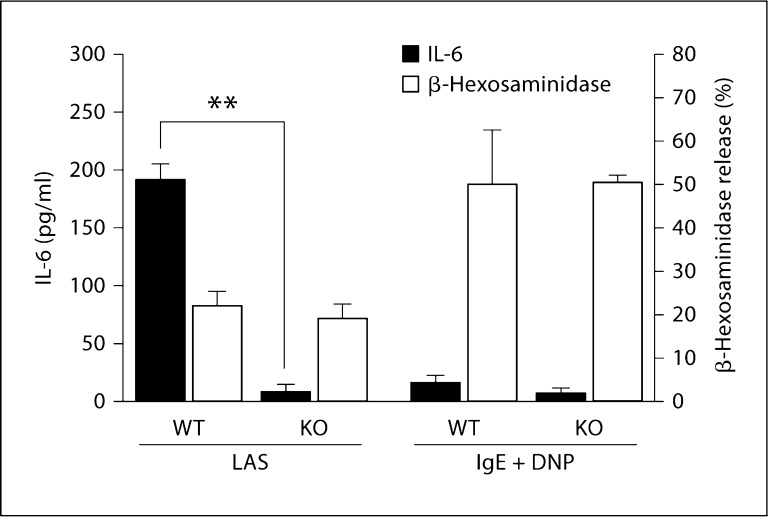

IL-6 secretion and β-hexosaminidase release (a measure of degranulation) by WT and α2-null FSMCs fol-lowing activation with either opsonized Listeria or IgE cross-linking was analyzed. Listeria opsonized with an immune complex stimulated IL-6 secretion from WT FSMCs, but not α2-null FSMCs, as previously reported (fig. 2) [5]. WT and α2-null FSMCs released similar low levels of β-hexosaminidase in response to Listeria plus an immune complex. In contrast, IgE cross-linking failed to stimulate IL-6 secretion from either WT or α2-null FSMCs at 1 h but resulted in a robust, α2-independent release of β-hexosaminidase at 1 h (fig. 2). These results indicate that mature connective tissue mast cells rapidly secreted IL-6 in response to Listeria in an α2β1 integrin-dependent manner. In contrast, IgE cross-linking failed to signal a rapid IL-6 release at this time point. Furthermore, degranulation in response to IgE cross linking was α2β1 integrin independent. The α2-null FSMCs maintained an adequate secretory function in response to IgE cross-linking and were not defective in terms of mast cell secretion to other stimuli.

Fig. 2.

Listeria- and α2β1 integrin-dependent IL-6 secretion in the absence of degranulation. WT and α2-null (KO) FSMCs (5 × 104 cells/well) were stimulated with Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum (LAS) for 1 h or anti-DNP IgE overnight followed by 1 h of stimulation with DNP-HSA (IgE + DNP). Cell-free supernatants were analyzed for the release of IL-6 (white bars) or β-hexosaminidase (black bars) via ELISA or as described in Materials and Methods, respectively. The secretion of IL-6 by α2-null (KO) FSMCs was significantly less than that by WT FSMCs (** p< 0.009). p values were determined using unpaired Student's t test. Data are expressed as means ± SEM and are representative examples of at least 3 similar experiments.

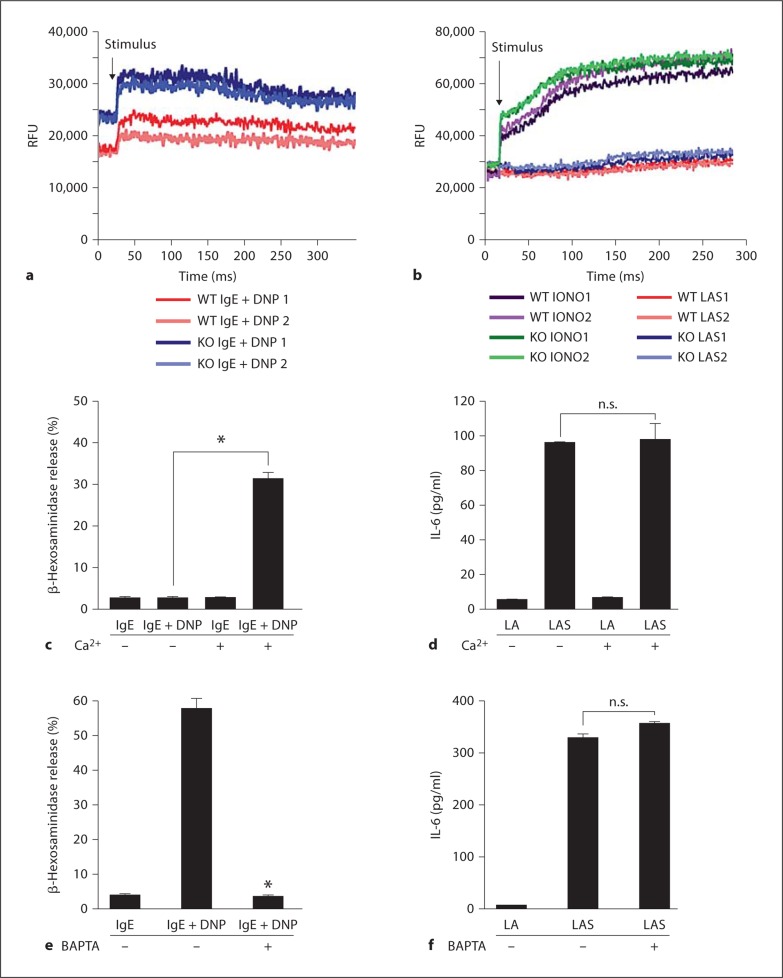

Mast cell degranulation following IgE cross-linking requires calcium mobilization, a crucial second messenger in downstream signaling events [14]. Calcium mobilization by WT or α2-null FSMCs in response to Listeria plus immune complex stimulation, IgE-cross-linking, or the calcium ionophore ionomycin was examined. Both WT and α2-null FSMCs mobilized calcium in a similar manner following stimulation with IgE cross-linking or ionomycin (fig. 3a, b). In contrast, neither WT nor α2-null FSMCs mobilized calcium following Listeria plus immune complex stimulation (fig. 3b), suggesting that IL-6 secretion in response to Listeria is calcium independent. To further examine the requirement of extracellular calcium mobilization for IL-6 secretion, FSMCs were activated by either IgE cross-linking or Listeria plus an immune complex in calcium-free and calcium-containing Hank's Balanced Salt Solution. Mast cell degranulation and histamine release stimulated by IgE cross-linking was inhibited in calcium-free media (fig. 3c). Mast cells activated by Listeria plus an immune complex secreted IL-6 in the presence or absence of calcium (fig. 3d). In addition, we inhibited intracellular calcium signaling with the calcium chelator BAPTA. Addition of BAPTA markedly reduced mast cell degranulation in response to IgE cross-linking (fig. 3e). In contrast, there was no defect in IL-6 secretion from WT FSMCs in response to Listeria plus an immune complex in the presence of BAPTA (fig. 3f). These results demonstrate that calcium mobilization is not required for α2β1 integrin-dependent IL-6 secretion but is required for degranulation in response to IgE cross-linking.

Fig. 3.

IL-6 secretion in the absence of calcium flux. a, b WT and α2-null (KO) FSMCs (1 × 106) were treated with anti-DNP IgE overnight and then stimulated with DNP-HAS (a) or Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum (LAS) or ionomycin (2 μm) (b). The time course of calcium flux from 2 independent experiments is shown in each graph. c, d WT FSMCs (5 × 104/well), in the presence or absence of Ca2+, were stimulated with either anti-DNP IgE followed by DNP-HAS (IgE + DNP) (c), Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody (LA), or LAS (d). Cell-free supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for either β-hexosaminidase (c) or IL-6 (d) levels. The presence of Ca2+ was required for the release of significant amounts of β-hexosaminidase. e, f WT FSMCs were preincubated for 15 min at 37° C with the calcium chelator BAPTA or media alone and then stimulated as described for c and d. Secretion of β-hexosaminidase (e), but not IL-6 (f), was inhibited in the presence of BAPTA, as determined by ELISA on cell-free supernatants. Experiments were performed in duplicate and results are expressed as means ± SEM. p values were determined using Student's t test (* p < 0.02).

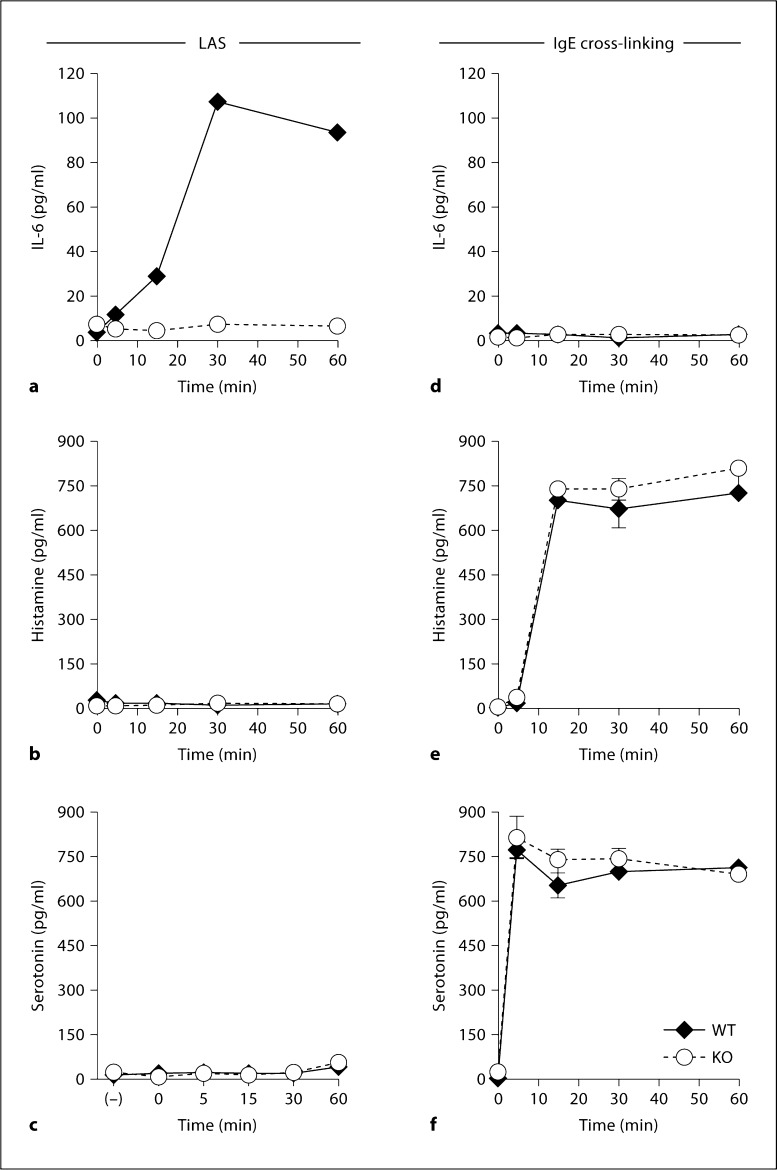

Mast cell degranulation in response to IgE cross-linking occurs within 0–10 min of stimulation and results in the release of histamine and serotonin, granule-associated mediators responsible for the allergic responses of IgE-mediated degranulation [21,22]. Our earlier studies examined IL-6 secretion only after 1 h [1,5,6]. The time course of IL-6 secretion following stimulation with the Listeria immune complex was compared to the time course of histamine and serotonin secretion following IgE cross-linking (fig. 4a–c). In response to Listeria plus an immune complex, WT, but not α2-null, FSMCs released low levels of IL-6 by 15 min. IL-6 secretion peaked after 30 min of stimulation (fig. 4a). The IL-6 levels remained elevated for 60 min. Neither histamine nor se-rotonin was detected following the stimulation of WT or α2-null FSMCs with the Listeria immune complex (fig. 4b, c). The release of IL-6 was not observed during the first hour following IgE cross-linking (fig. 4d). In contrast, both WT and α2-null FSMCs released high levels of histamine and serotonin within 5–10 min of Fc∊R activation (fig. 4e, f). The magnitude and kinetics of release by WT and α2-null FSMCs were identical. However, IL-6 was secreted at later time points following IgE cross-linking (see below). These results demonstrate that mast cell activation via stimulation with either IgE cross-linking or Listeria plus an immune complex results in the differential secretion of immune modulators by nonoverlapping pathways with different kinetics.

Fig. 4.

Time course of IL-6, histamine, and serotonin secretion. WT and α2-null (KO) FSMCs (5 × 104/well) were treated overnight with either Listeria plus antibody and serum (LAS) (a-c) or anti-DNP IgE followed by stimulation with DNP-HSA (IgE + DNP) (d-f) for the indicated time points. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-6 (a, d), histamine (b, e), or serotonin (c, f). Data are presented as means ± SEM and are representative of at least 3 similar experiments.

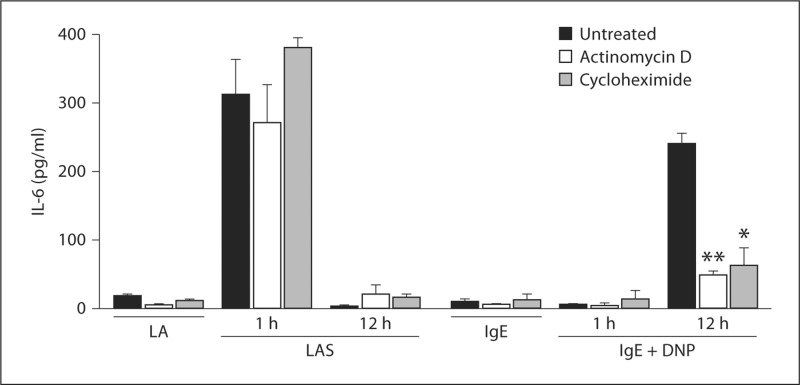

Histamine and serotonin are both preformed mediators and they are rapidly released upon IgE-stimulation. Although previous reports have demonstrated that IL-6 is synthesized de novo by mast cells, the rapid nature of IL-6 release in response to Listeria plus an immune complex suggested that IL-6 is also stored in the mast cell [23,24]. To determine if IL-6 was preformed or rapidly synthesized following stimulation, transcription and translation were inhibited using actinomycin D and cycloheximide, respectively. Treatment of FSMCs with actinomycin D or cycloheximide failed to inhibit IL-6 release by WT FSMCs after 1 h of immune complex stimulation (fig. 5). The lack of inhibition by actinomycin D and cycloheximide suggested that IL-6 is preformed and not synthesized de novo and that α2β1 integrin-mediated mast cell activation results in the release of a preformed IL-6 pool. In contrast, IL-6 was not rapidly secreted following IgE cross-linking. However, IL-6 was synthesized de novo and released 12 h after IgE cross-linking, as previously reported [25,26]. The de novo synthesis of IL-6 was inhibited by actinomycin D and cycloheximide.

Fig. 5.

IL-6 secretion is independent of transcription or translation. WT FSMCs (5 × 104/well) were stimulated with Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody (LA) or Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum (LAS) for 1 or 12 h at 37°C in the presence or absence of actinomycin D or cycloheximide. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-6 by ELISA. Results are presented as means ± SEM and are representative of 1 of at least 3 separate experiments. p values were determined using Student's t test (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01).

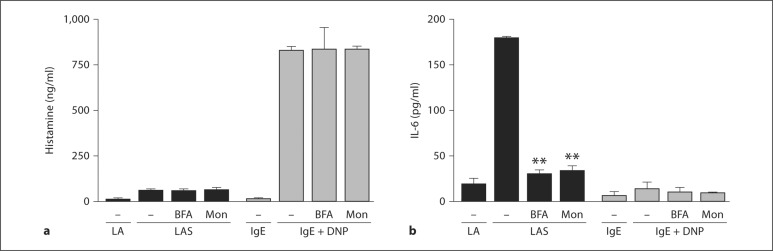

To directly address the transport pathway for IL-6 secretion, we inhibited trans-Golgi protein transport with BFA or monensin. The release of histamine by IgE cross linking was not significantly inhibited by either BFA or monensin (fig. 6a). As shown above, Listeria plus an immune complex failed to stimulate histamine release (fig. 6a). In contrast, the α2β1 integrin-dependent Listeria-stimulated release of IL-6 at 1 h was inhibited by both BFA and monensin (fig. 6b). IgE cross-linking did not result in rapid secretion of IL-6 (fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

IL-6 but not histamine release requires endosomal trafficking. WT FSMCs (5 × 104/well) were stimulated with Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody (LA), Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum (LAS), anti-DNP IgE overnight (IgE), or anti-DNP IgE overnight plus DNP-HSA (IgE + DNP) at 37°C in the presence or absence of monensin (Mon) or BFA. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for histamine (a) or IL-6 (b) by ELISA. Results are presented as means ± SEM and are representative of 1 of at least 3 separate experiments. p values were determined using Student's t test (** p < 0.01).

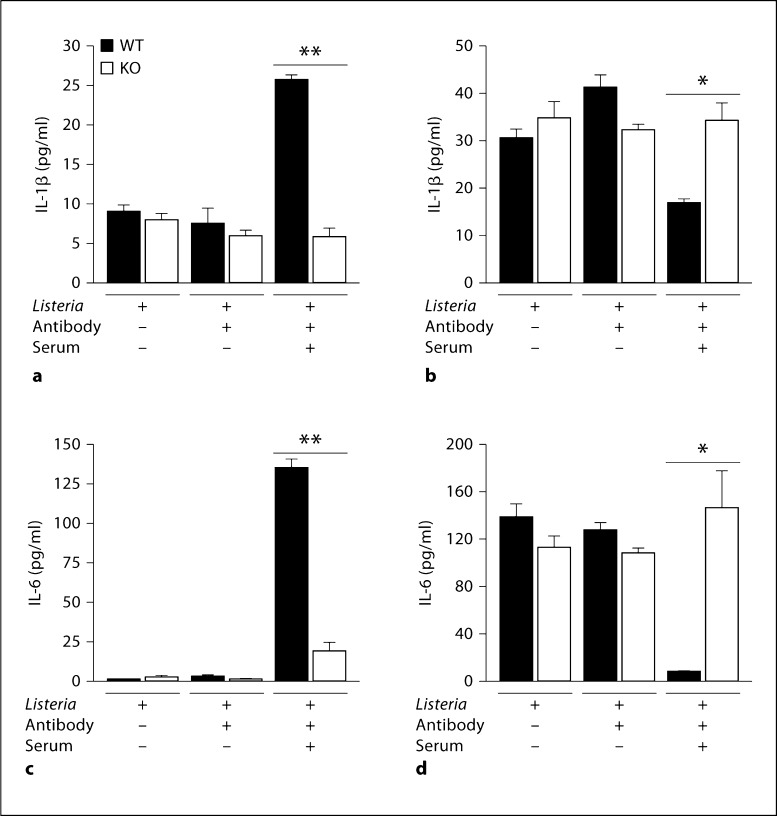

In our earlier report, WT mice, but not α2-null mice, responded to Listeria in vivo by producing not only IL-6 but also IL-1β. In the intact animal, IL-1β is secreted by mast cells as well as other cells of the innate immune system, including macrophages that reside within the peritoneal cavity. To determine if the in vivo cytokine response to Listeria was entirely a result of mast cell secretion of the cytokines or a result of downstream activation of other cells, the secretion of IL-1β by FSMCs in response to Listeria plus an immune complex was analyzed in vitro. WT FSMCs secreted both IL-1β and IL-6 when stimulated with opsonized Listeria. In contrast, α2-null FSMCs failed to secrete either IL-1β or IL-6 (fig. 7a, c). Therefore, IL-1β is directly secreted by FSMCs in response to Listeria in an integrin-dependent manner.

Fig. 7.

Immune complex-induced Il-6 and IL-1β secretion. WT and α2-null (KO) FSMCs (5 × 104/well) were stimulated with Listeria, Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody, or Listeria plus anti-Listeria antibody and serum at 37°C. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-1β (a) or IL-6 (c) by ELISA. FSMCs were lysed after stimulation as described above, and total cellular content was analyzed by ELISA for IL-1β (b) or IL-6 (d). Results are presented as means ± SEM and experiments were performed in duplicate. p values were determined using Student's t test (** p < 0.01; * p = 0.04).

Based on the previous literature, the presence of preformed IL-6 in FSMCs was unexpected. To address whether integrin-dependent activation led to secretion of the entire storage pool of IL-6, the total cellular content of IL-6 in resting FSMCs was compared to FSMCs after integrin-mediated stimulation and the amount of secreted IL-6. As shown in figure 7d, the entire pool of IL-6 in resting FSMCs was secreted following activation. After FSMC stimulation, the mast cells were devoid of detectable IL-6. The intracellular stores of IL-1β were partially but significantly depleted after activation (fig. 7b).

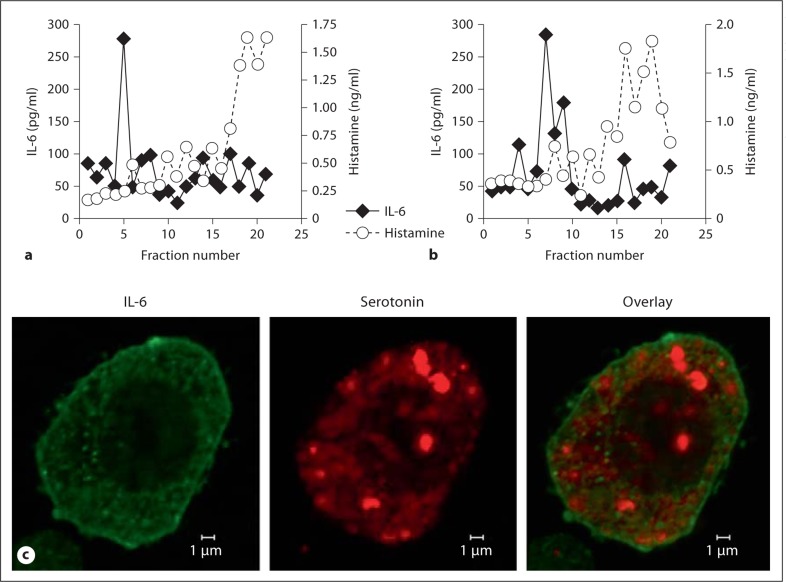

Earlier studies demonstrated that de novo synthesized IL-6 is present in small vesicles distinct from the granules that contain tryptase in human umbilical cord blood-derived mast cells [18,21,27]. To characterize the distinct granule fraction, PNS from both WT and α2-null FSMCs were isolated and separated via Percoll-density separation based on granule size. The contents of each fraction were analyzed by ELISA for IL-6 and histamine concentration (fig. 8a, b). IL-6 was enriched in a subset of fractions (fractions 5–7) representing the smaller-sized vesicles. Only low levels of IL-6 were detected in the remaining fractions. Histamine was primarily separated into high-density fractions, suggestive of larger-sized vesicles (fractions 16–19). Both WT and α2-null FSMCs demonstrated a similar distribution and quantity of IL-6 and histamine in the fractions. These data suggest that IL-6 and histamine are not only selectively released but also differentially stored in mast cells.

Fig. 8.

Preformed IL-6 is stored in small vesicles. PNS from WT (a) and α2-null (b) FSMCs (1 × 107) were separated over a 2-layer Percoll gradient (1.05 and 1.12 g/ml). Two hundred-microliter fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. Each fraction was analyzed by ELISA for IL-6 and histamine. c Confocal immunofluorescence analysis detected IL-6 (green; colors refer to online version only) and serotonin (red) within separate and distinct mast cell granules. The image is representative of 3 separate experiments.

Using serotonin as a marker of mast cell granules, we employed confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to characterize the subcellular localization of IL-6 and serotonin in mast cell granules [18,21,27]. As seen in figure 8c, IL-6 (green) was visualized in small vesicles located diffusely throughout the cell, as well as in close proximity to the cytoplasm interface of the plasma membrane. Serotonin (red), on the other hand, was stored primarily in large granules and some smaller granules throughout the cell. In the merged image there is no overlap, demonstrating that serotonin and IL-6 were not colocalized. Taken together, these results demonstrate that mast cells store IL-6 and histamine in distinct and separate compartments that are selectively released in response to different stimuli.

Discussion

We have now defined an integrin- and c-met-dependent secretory pathway for the mast cell secretion of preformed IL-6 and IL-1β in response to L. monocytogenes [1,5]. The preformed IL-6 was stored in a distinct mast cell vesicle that lacked histamine or serotonin. The vesicle localization of IL-6 in our study is similar to the localization of newly synthesized IL-6, as previously described by Kandere-Grzybowska et al. [28]. Our findings, however, demonstrate a novel, α2β1 integrin-dependent pathway for mast cell stimulation distinct from the IgE-mediated secretion of mediators required for allergy and anaphylaxis. In addition, we demonstrate that preformed IL-6 resides within connective tissue mast cells, providing an immediate source for cytokine secretion. These data also demonstrate that, although IL-6 secretion in response to Listeria is dependent on the α2β1 integrin, IgE cross-linking-induced mast cell activation and secretion of histamine and serotonin does not require the α2β1 integrin.

Secretion of IL-6 from BMMCs in the absence of degranulation has been reported as part of the innate immune/inflammatory response to CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides, bacterial lipopolysaccharides, IL-1, SCF, and IgE cross-linking [23,28,29,30]. In all of these studies, IL-6 was synthesized de novo and was not released until 6–24 h after stimulation. The rapid time course of IL-6 release in WT mice following the introduction of Listeria in our model suggested that IL-6 was preformed and stored. The ability of PMCs to secrete IL-6 even when transcription and translation was inhibited by either actinomycin D or cycloheximide confirmed that the cytokine was preformed and stored within PMCs. As previously reported, IL-6 was secreted in response to IgE cross-linking, but only after 12 h, and required de novotranscription and translation [25,26]. Earlier studies have demonstrated that IgE cross linking results in the transcriptional regulation of IL-6 via the NF-κB pathway [26]. These data suggest that mast cell secretion of IL-6 is regulated by 2 distinct pathways. In one, IL-6 is transcriptionally regulated and secreted at later time points in response to IgE-cross-linking. In the other, IL-6 is stored in preformed pools and released upon specific stimuli.

For many years the primary role of mast cells was considered to be the rapid degranulation following IgE cross-linking that led to anaphylaxis [7]. Recent evidence suggests that mast cells play many roles in the innate and adaptive immune response [7,31,32,33]. Our data support a mechanism whereby IL-6 is stored and secreted from a granule distinct from the granules containing serotonin or histamine. Recently, a detailed analysis of mast cell degranulation demonstrated that histamine and serotonin are secreted via the same mechanisms but from distinct granules [18]. The serotonin- and histamine-containing granules identified by Puri and Roche [18] were indistinguishable by size. Differential release of serotonin and histamine from these 2 otherwise indistinguishable larger granules required distinct modes of vesicle trafficking and different SNARE proteins, one requiring VAMP8 and one being independent of VAMP8 [18,27]. In our studies using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, IL-6 was not stored in large granules but rather was stored in smaller vesicles. This was further confirmed by separating the granule populations on a 2-layer Percoll gradient. The localization of this preformed IL-6 in small vesicles is similar to earlier descriptions of the localization of IL-6 when synthesized de novo. Here, we demonstrate that a preformed pool of IL-6 can be released through activation of a distinct receptor, the α2β1 integrin, via a calcium-independent pathway.

Previous work has shown that rapid IL-6 release in response to the nonspecific calcium ionophore A23187 is sensitive to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) inhibitors BFA and monensin [34]. Although α2β1 integrin- and Listeria-mediated IL-6 secretion was calcium independent, secretion was sensitive to inhibition by these 2 well-characterized protein secretion inhibitors with defined mechanisms of action on TGN vesicular transport. In contrast, IgE-stimulated degranulation was insensitive to BFA or monensin. These data are in accordance with previous data that demonstrated that IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation is independent of classical protein exocytosis via the TGN [34]. Our results suggest that mast cells contain several distinct granule pools that have different requirements for the TGN which are stimulated for release by separate stimuli.

In addition to mast cells, platelets, NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, neutrophils, and endothelial cells express the α2β1 integrin and contain granules rich in inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and angiogenic stimulators. Platelets are activated upon stimulation with collagen through the α2β1 integrin and its co-receptor, GPVI [35]. Cross-linking of the α2β1 integrin on NK cells with an α2β1 integrin-specific antibody resulted in decreased cell motility and diminished cellular cytotoxicity [36]. In addition, in a non-granule-containing CD4+ T cell subset, α2β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to type I collagen enhanced IFN-γ production by anti-CD3 antibody [37]. These observations suggest that α2β1 integrin expression by multiple hematopoietic cell types may modulate the inflammatory/immune function of these cells.

In summary, our data define an α2β1 integrin-dependent pathway that leads to the release of preformed and prestored IL-6 by connective tissue mast cells. The rapid secretion of IL-6 results in activation of the innate immune response to L. monocytogenes. We provide convincing evidence that the secretory pathway leading to IL-6 release in response to Listeria is different from the pathway leading to degranulation in response to IgE cross-linking. The data demonstrate an additional way and a new receptor by which mast cells serve as the sentinels of the innate immune response, poised at the surfaces first exposed to assault by the external environment [38].

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laura Ford and Ping Zhao for expert animal care, as well as Jean McClure for secretarial assistance. This work was supported by grants 5R01 CA115984-05 and 2R01 CA098027-07 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Edelson BT, Li Z, Pappan LK, Zutter MM. Mast cell-mediated inflammatory responses require the alpha 2 beta 1 integrin. Blood. 2004;103:2214–2220. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caswell CC, Lukomska E, Seo NS, Hook M, Lukomski S. Scl1-dependent internalization of group A Streptococcus via direct interactions with the alpha2beta(1) integrin enhances pathogen survival and re-emergence. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1319–1331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciarlet M, Crawford SE, Cheng E, et al. VLA-2 (alpha2beta1) integrin promotes rotavirus entry into cells but is not necessary for rotavirus attachment. J Virol. 2002;76:1109–1123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1109-1123.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter M, Ray SJ, Chapman TJ, et al. Collagen distribution and expression of collagen-binding alpha1beta1 (VLA-1) and alpha2beta1 (VLA-2) integrins on CD4 and CD8 T cells during influenza infection. J Immunol. 2007;178:4506–4516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelson BT, Stricker TP, Li Z, et al. Novel collectin/C1q receptor mediates mast cell activation and innate immunity. Blood. 2006;107:143–150. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCall-Culbreath KD, Li Z, Zutter MM. Crosstalk between the alpha2beta1 integrin and c-met/HGF-R regulates innate immunity. Blood. 2008;111:3562–3570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall JS. Mast-cell responses to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:787–799. doi: 10.1038/nri1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malaviya R, Ross E, Jakschik BA, Abraham SN. Mast cell degranulation induced by type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli in mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1645–1653. doi: 10.1172/JCI117146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malaviya R, Ikeda T, Ross E, Abraham SN. Mast cell modulation of neutrophil influx and bacterial clearance at sites of infection through TNF-alpha. Nature. 1996;381:77–80. doi: 10.1038/381077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Echtenacher B, Mannel DN, Hultner L. Critical protective role of mast cells in a model of acute septic peritonitis. Nature. 1996;381:75–77. doi: 10.1038/381075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundstrom JB, Ellis JE, Hair GA, et al. Human tissue mast cells are an inducible reservoir of persistent HIV infection. Blood. 2007;109:5293–5300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-058438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall JS, Jawdat DM. Mast cells in innate immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jawdat DM, Rowden G, Marshall JS. Mast cells have a pivotal role in TNF-independent lymph node hypertrophy and the mobilization of Langerhans cells in response to bacterial peptidoglycan. J Immunol. 2006;177:1755–1762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metzger H, Rivnay B, Henkart M, Kanner B, Kinet JP, Perez-Montfort R. Analysis of the structure and function of the receptor for immunoglobulin E. Mol Immunol. 1984;21:1167–1173. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(84)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Logan MR, Odemuyiwa SO, Moqbel R. Understanding exocytosis in immune and inflammatory cells: the molecular basis of mediator secretion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:923–932. quiz 933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parravicini V, Gadina M, Kovarova M, et al. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishida K, Yamasaki S, Ito Y, et al. Fc∊RI-mediated mast cell degranulation requires calcium-independent microtubule-dependent translocation of granules to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:115–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puri N, Roche PA. Mast cells possess distinct secretory granule subsets whose exocytosis is regulated by different SNARE isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2580–2585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707854105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada N, Matsushima H, Tagaya Y, Shimada S, Katz SI. Generation of a large number of connective tissue type mast cells by culture of murine fetal skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1425–1432. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajotte D, Stearns CD, Kabcenell AK. Isolation of mast cell secretory lysosomes using flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 2003;55:94–101. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olszewski MB, Trzaska D, Knol EF, Adamczewska V, Dastych J. Efficient sorting of TNF-alpha to rodent mast cell granules is dependent on N-linked glycosylation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:997–1008. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfeiffer JR, Seagrave JC, Davis BH, Deanin GG, Oliver JM. Membrane and cytoskeletal changes associated with IgE-mediated serotonin release from rat basophilic leukemia cells. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2145–2155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu FG, Marshall JS. CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides induce TNF-alpha and IL-6 production but not degranulation from murine bone marrow-derived mast cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:253–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushima H, Yamada N, Matsue H, Shimada S. TLR3-, TLR7-, and TLR9-mediated production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from murine connective tissue type skin-derived mast cells but not from bone marrow-derived mast cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:531–541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marquardt DL, Walker LL. Dependence of mast cell IgE-mediated cytokine production on nuclear factor-kappaB activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:500–505. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.104942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalesnikoff J, Baur N, Leitges M, et al. SHIP negatively regulates IgE + antigen-induced IL-6 production in mast cells by inhibiting NF-kappa B activity. J Immunol. 2002;168:4737–4746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiwari N, Wang CC, Brochetta C, et al. VAMP-8 segregates mast cell-preformed mediator exocytosis from cytokine trafficking pathways. Blood. 2008;111:3665–3674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandere-Grzybowska K, Letourneau R, Kempuraj D, et al. IL-1 induces vesicular secretion of IL-6 without degranulation from human mast cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:4830–4836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supajatura V, Ushio H, Nakao A, et al. Differential responses of mast cell Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in allergy and innate immunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1351–1359. doi: 10.1172/JCI14704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gagari E, Tsai M, Lantz CS, Fox LG, Galli SJ. Differential release of mast cell interleukin-6 via c-kit. Blood. 1997;89:2654–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakae S, Suto H, Iikura M, et al. Mast cells enhance T cell activation: importance of mast cell costimulatory molecules and secreted TNF. J Immunol. 2006;176:2238–2248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skokos D, Le Panse S, Villa I, et al. Mast cell-dependent B and T lymphocyte activation is mediated by the secretion of immunologically active exosomes. J Immunol. 2001;166:868–876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malaviya R, Abraham SN. Role of mast cell leukotrienes in neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance in infectious peritonitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:841–846. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.6.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu FG, Gomi K, Marshall JS. Short-term and long-term cytokine release by mouse bone marrow mast cells and the differentiated KU-812 cell line are inhibited by brefeldin A. J Immunol. 1998;161:2541–2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santoro SA, Zutter MM. The alpha 2 beta 1 integrin: a collagen receptor on platelets and other cells. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:813–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrod KR, Wei SH, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Natural killer cells actively patrol peripheral lymph nodes forming stable conjugates to eliminate MHC-mismatched targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12081–12086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702867104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boisvert M, Gendron S, Chetoui N, Aoudjit F. Alpha2 beta1 integrin signaling augments T cell receptor-dependent production of interferon-gamma in human T cells. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3732–3740. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1215–1223. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]