Abstract

The goals of a T cell-based vaccine for HIV are to reduce viral peak and setpoint and prevent transmission. While it has been relatively straightforward to induce CD8+ T cell responses against immunodominant T cell epitopes, it has been more difficult to broaden the vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell response against subdominant T cell epitopes. Additionally, vaccine regimens to induce CD4+ T cell responses have been studied only in limited settings. In this study, we sought to elicit CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cells using various novel and well-established vaccine strategies. We vaccinated three Mamu-A*01+ animals with five Mamu-A*01-restricted subdominant SIV-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes. All three vaccinated animals made high frequency responses against the Mamu-A*01-restricted Env TL9 epitope with one animal making a low frequency CD8+ T cell response against the Pol LV10 epitope. We also induced SIV-specific CD4+ T cells against several MHC class II DRBw*606-restricted epitopes. Electroporated DNA with pIL-12 followed by a rAd5 boost was the most immunogenic vaccine strategy. We induced responses against all three Mamu-DRB*w606-restricted CD4 epitopes in the vaccine after the DNA prime. Ad5 vaccination further boosted these responses. Although we successfully elicited several robust epitope-specific CD4+ T cell responses, vaccination with subdominant MHC class epitopes elicited few detectable CD8+ T cell responses. Broadening the CD8+ T cell response against subdominant MHC class I epitopes was, therefore, more difficult than we initially anticipated.

INTRODUCTION

Due to the variability of HIV, a vaccine for this virus needs to engender CD8+ T cell responses against several different epitopes. Eliciting only a few HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses will be ineffective if the challenge virus already contains amino acid substitutions within those CD8 epitopes. Including subdominant epitopes in a vaccine should broaden the HIV/SIV-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire and allow vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes the opportunity to expand upon HIV/SIV infection, at which time normally immunodominant responses will most likely also be generated.

In order to increase CD8+ T cell breadth, it will be necessary to alter the natural immunodominance of the HIV- or SIV-specific CD8+ T cell response. Importantly, inducing CD8+ T cell responses against immunodominant epitopes can suppress the development of potentially effective subdominant responses both in the setting of a vaccine regimen and after viral challenge [1–5]. During natural infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), Balb/C mice mount an immunodominant response to peptide D (NP118–126) and a subdominant response to peptide WX (NP313–322). Vaccination with these two epitopes expressed from a single plasmid that contains the immunodominant epitope (peptide D) will suppress responses to the subdominant epitope (peptide WX). Separating the immunodominant epitope from the subdominant epitope by vaccinating with two different plasmids overcomes this problem [5]. Additionally, during natural infection with LCMV, C57Bl/6 mice mount an immunodominant response to peptide GP33 and a subdominant response to peptide NP396; however, the immunodominant immune response against GP33 is less efficient at controlling LCMV replication than the subdominant immune response against peptide NP396 [3]. An effective HIV vaccine may, therefore, benefit from induction of subdominant CD8+ T cell responses.

The role of CD4+ T cells in HIV/SIV infection is far more unclear. CD4+ T cells are required for proper development and maintenance of CD8+ T cells [6,7]. Additionally, CD4+ T cells play a critical role in providing help for CD8+ T cells [8,9]. Furthermore, virus-specific CD4+ T cell responses are well preserved in both elite controller (EC) SIV-infected rhesus macaques and HIV-infected humans [10–15]. ECs are HIV- or SIV- infected individuals or animals that maintain low or undetectable viral loads. Although together these studies suggest an important role for virus-specific CD4+ T cells in reducing HIV/SIV viral replication, it is difficult to discern whether the high frequency and broad repertoire of HIV/SIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses is a result of the intact, healthy immune system of ECs or if they directly or indirectly contribute to control of viral replication.

Autologous dendritic cells (DCs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) have been used to expand HIV/SIV-specific responses in vivo [16–18]. Using DCs pulsed with aldrithiol-2 (AT-2)-inactivated HIV, Lu et al. observed significant expansion of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected patients [17]. Therapeutic DCs successfully suppressed viral loads in eight of the 18 tested individuals. Lu et al. also showed decreased SIV DNA and RNA in SIV-infected rhesus macaques by vaccinating animals with AT-2-inactivated SIV-pulsed autologous DCs [18]. Multiple infusions of autologous PBMC pulsed with peptides into SHIV-infected macaques expanded both Gag- and Pol-specific SIV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses [16]. Thus far, however, these vaccine regimens have been used only as therapeutic vaccines.

Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) carrier gene fused with SIV epitopes was previously shown to stimulate CD8+ T cell responses in rhesus macaques [19]. Though this vaccination regimen induced SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in all macaques, the majority of responses were against the two immunodominant Mamu-A*01-restricted epitopes, Gag181–189CM9 (Gag CM9) and Tat28–35SL8 (Tat SL8). Few vaccine regimens have successfully induced epitope-specific responses; however, peptides conjugated to 50-nm inert carboxylated polystyrene nanobeads can elicit both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses [20–23]. Vaccination with nanobeads conjugated with OVA peptides induced OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in both mice and sheep [21,24,25]. Additionally, OVA-specific nanobead-induced CD8+ T cells delayed tumor growth after challenge with EG7 tumor cells 30 days after the final immunization.

In this study, therefore, we sought to engender CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant epitopes and epitope-specific CD4+ T cells using several novel and well-tested T cell based vaccine strategies. Electroporation of DNA with plasmid IL-12 (pIL-12) followed by rAd5 boosting induced high frequency responses against the Mamu-A*01-restricted Env TL9 subdominant epitope; however few other SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant epitopes were detected. This regimen also elicited high frequency SIV-specific CD4+ T cells to all epitopes in the vaccine. While the electroporated DNA/rAd5 vaccine regimen successfully engendered SIV-specific CD4+ T cells; eliciting CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes in a vaccine was much more difficult.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center were cared for according to the regulations and guidelines of the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Breeding colony animals were typed for MHC class I allele Mamu-A*01 and MHC class II allele Mamu-DRBw*606 by sequence-specific PCR [26,27].

Vaccine priming with peptide-pulsed autologous dendritic cell

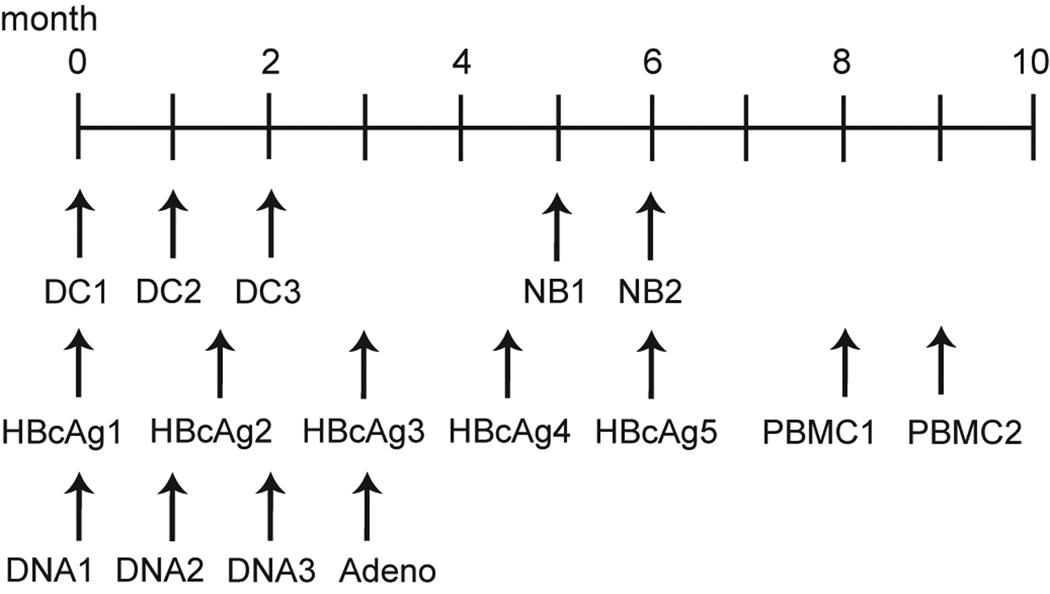

Dendritic cells (DCs) were generated and cultured as previously described [18,28,29]. Briefly, monocytes were isolated from PBMC from a large blood draw using non-human primate CD14 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and cultured in complete RPMI (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, 2mM L-glutamine, and 50 µg/ml antimycotic/antibiotic- all purchased from HyClone Laboratories, Inc.) supplemented with 100 U/ml IL-4 and 1000 U/ml of GM-CSF. Each well containing 1.5e6–3e6 CD14+ cells were then pulsed with either approximately 30 µg of peptide or 1.5 µg of Gag p27CA AT-2-inactivated SIVmac239/1e6 cells for two hours at 37°C, washed, and incubated for 24–48 hours at 37°C. A cocktail of proinflammatory mediators (1000 U/ml TNF-α, 10 ng/ml il-1β, 10 ng/ml IL-6 and 1µM PGE2) was then added to the DCs to induce full DC maturation. Cells were incubated for an additional 24–48 hours, harvested, washed and resuspended in 1× PBS, and loaded into a 27G needle for subcutaneous vaccination. Animals in Groups 4 and 5 were vaccinated three times one month apart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of vaccination timeline.

DC: autologous dendritic cell transfer; NB: peptide-conjugated nanobeads; HBcAg: Hepatitis B core antigen carrier gene; PBMC: autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cell transfer; DNA: electroporated DNA + IL-12; Adeno: Adenovirus 5.

Vaccine boosting with peptide-pulsed autologous PBMC

We generated and peptide-pulsed autologous PBMC as previously described [16]. Briefly, PBMC were isolated from a large blood draw and resuspended in PBS. PBMC were divided into 0.5 ml containing 1e7–2e7 PBMC and pulsed with 10 µg/ml of peptide for 60–90 minutes in a 37°C water bath. Cells were then mixed, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS, and loaded into a 25G needle for vaccination. Animals in Groups 2 and 5 were vaccinated twice one month apart (Figure 1).

Vaccine priming with Hepatitis B core antigen carrier gene

DNA vaccines expressing a fusion of SIV-specific CD8 epitopes to the HBcAg carrier gene were generated as previously described [19]. Mamu-A*01+ epitopes were inserted into WRG7198 cut with PspMO1 and Xma1. Ligation reactions were transfected into NEB 5-alpha cells (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), and resulting colonies were screened for insert presence and confirmed by sequencing. Murine B16 cells were transfected with these plasmids using Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cell supernatants and cell lysates (in PBS/0.05% triton X-100) were spun at 21Kg for 10 minutes to remove debris, loaded on a 500 µl pad of 20% glycerol and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 46K rpm for three hours in a TLA55 rotor. The pellets were resuspended in 250 µl of PBS and analyzed using the ETI-EBK Plus ELISA kit (Diasorin, Inc. Stillwater MN). All samples exhibited absorbances greater than the kit’s positive control, indicating that each HBcAg-SIV epitope plasmid expressed hepatitis core virus-like particles. Separate HBcAg-SIV epitope fusion plasmids were generated for each of the five subdominant Mamu-A*01-restricted CD8 epitopes. Plasmid DNA was precipitated onto 1- to 3-µm gold particles at a rate of 2.0 µg DNA/mg of gold. Each individual plasmid was coated on separate gold beads and then the beads were mixed prior to gene gun delivery. DNA-coated gold particles were accelerated into the abdominal and inguinal lymph node regions of rhesus macaques by particle mediated epidermal delivery (PMED) using an XR-1 research delivery device (PowderJect Vaccines, Inc.) as previously described [30]. DNA/gold was delivered at a helium pressure of 500–600 psi. Animals received 1 mg of gold particles and 2 µg of DNA per delivery site for a total of 16 epidermal doses, 16 mg of gold particles, and 32 µg of DNA per dose. DNA vaccinations were at least four weeks apart. Animals in Group 1 and 2 received five total HBcAg-SIV immunizations (Figure 1).

Peptide-conjugated nanobeads for in vitro stimulation and vaccine boosting

FITC-avidin carbon nanobeads were produced as previously described [31]. Peptides were conjugated to nanobeads by adding 10 mg/ml to 2% nanobeads. The peptide-nanobead mixture was tumbled overnight at 4°C, washed once in PBS+azide and twice in PBS to remove unbound peptide. The peptide-conjugated nanobeads were then resuspend in PBS for use in vitro and in vivo. Nanobeads were used for vaccinations as previously described [20,22]. Briefly, we used 400 µg of CpG DNA (Sigma)/animal and thoroughly mixed the peptide-conjugated nanobead + CpG DNA solution with an equal volume of Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant before loading 27G needles. Animals in Groups 1 and 4 were subcutaneously vaccinated twice one month apart with 1 mg of each epitope (Figure 1).

Vaccine priming with DNA using Electroporation

The plasmid vaccines used in this study encoded either CD8 or CD4 epitopes separated by GGS/GGGS linker sequences. Plasmid design was based on vector 8L-CMVhuLAMPkan [32,33]. The CD8-A*01 and CD4-w606 epitopes were fused to the hLAMP-1 protein (GenBank accession number NM005561), between the luminal sequence and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail (TM/cyt) domain. The hLAMP-1-CD8 and hLAMP-1-CD4 epitope fusion coding sequences were optimized for expression in mammalian cells and cloned into a plasmid expression vector. Expression of the intronless coding sequences was controlled by the human CMV (hCMV) promoter/enhancer and the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal [32]. Protein expression after transient transfection of HEK 293T cells was confirmed by Western blot using anti-hLAMP-1 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Large-scale plasmid lots used for immunization were prepared by Aldevron, LLC. DNA vaccination was administered by electroporation as previously described [34–36]. Animals were given 1 mg of either the CD8 (Group 3) or the CD4 (Group 6) DNA construct intramuscularly with 10 µg of rhesus plasmid IL-12 DNA (pIL-12) (AG157, Aldevron). Rhesus pIL-12 was expressed from a dual promoter plasmid including the human CMV immediate early promoter (hCMV) and SV40 polyadenylation signal, and the simian CMV promoter (sCMV) and BGH polyadenylation signal [37]. Animals were given three DNA primes each one month apart (Figure 1).

Vaccine boosting with recombinant Adenovirus 5

rAd5 constructs were made by Viraquest, Inc. as previously described [38]. DNA constructs containing either the CD8 or CD4 epitopes linked by GPGPG sequences were produced by GenScript with HindIII and BamHI restriction sites added to the 5’ and 3’ ends, respectfully. Plasmids were digested with HindIII-BamHI enzymes and subcloned by standard methods into pVQAd CMV K-NpA shuttle plasmid (Viraquest, Inc). Fifteen micrograms of shuttle plasmid and 5 µg of pVQAd 9.2–100 backbone plasmid were digested with PacI. Both linear fragments were then co-transfected into HEK293 cells in a 60 mm plate at ~50% confluency by standard CaCl2 method. The initial viral lysate was amplified in HEK293 cells and the final viral lysate purified over two rounds of CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation. Virus particles were dialyzed, diluted to 1e12 particles/ml as measured by optimal density (OD260), and frozen at −80°C. Infectious particle concentration was then assayed by a cell-based plaque assay on HEK293 cells. Presence of replication competent adenovirus was checked by plaquing on wild type permissive A549 cells for at least 14 days. Adenovirus had the E1 region deleted and a portion of the E3 region deleted. Animals were vaccinated intramuscularly with 1e10 particles of rAd5 in 0.5 ml of culture buffer or PBS. Animals in Groups 3 and 6 were given one rAd5 boost one month after the final DNA prime (Figure 1).

In vitro nanobead stimulation

PBMC was isolated from blood of an SIV-infected rhesus macaque and stimulated with either CD8 or CD4 epitopes conjugated to nanobeads. PBMC were cultured for two days with complete RPMI containing 10 ng of recombinant human IL-7 and cultured for a further 5 days with complete RPMI containing 100 U/ml of IL-2. The culture was harvested after one week and assessed for interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) as previously described [39].

IFN-γ Enzyme-linked immunospot assay

ELISPOT (Mabtech) assays were performed using freshly isolated PBMC as previously described [40]. Briefly, 1×105 PBMC per well were stimulated with peptide in a precoated ELISPOT plate according to the manufacturer’s instructions and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator overnight. All tests were performed in duplicate using individual peptides at 10 µM. Fifteen-mer peptides were provided by the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD). Recombinant HepBcAg peptide was purchased from Biodesign International (Meridian Life Sciences). Plates were imaged using an ELISPOT reader (Autoimmun-Diagnostika), counted by ELISPOT Reader version 4.0 (Autoimmun-Diagnostika), and analyzed as previously described [41].

RESULTS

Several vaccine regimens have successfully induced SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses against immunodominant epitopes; however, eliciting SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes has been far more complicated. Additionally, inducing epitope-specific CD4+ T cells by vaccination has not been thoroughly investigated. In this study, we inserted subdominant CD8 and CD4 SIV epitope sequences into both novel and well-tested vectors to determine the most immunogenic regimen for inducing CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes and epitope-specific CD4+ T cells.

In vitro expansion of SIV-specific T cells using carbon-based nanobeads

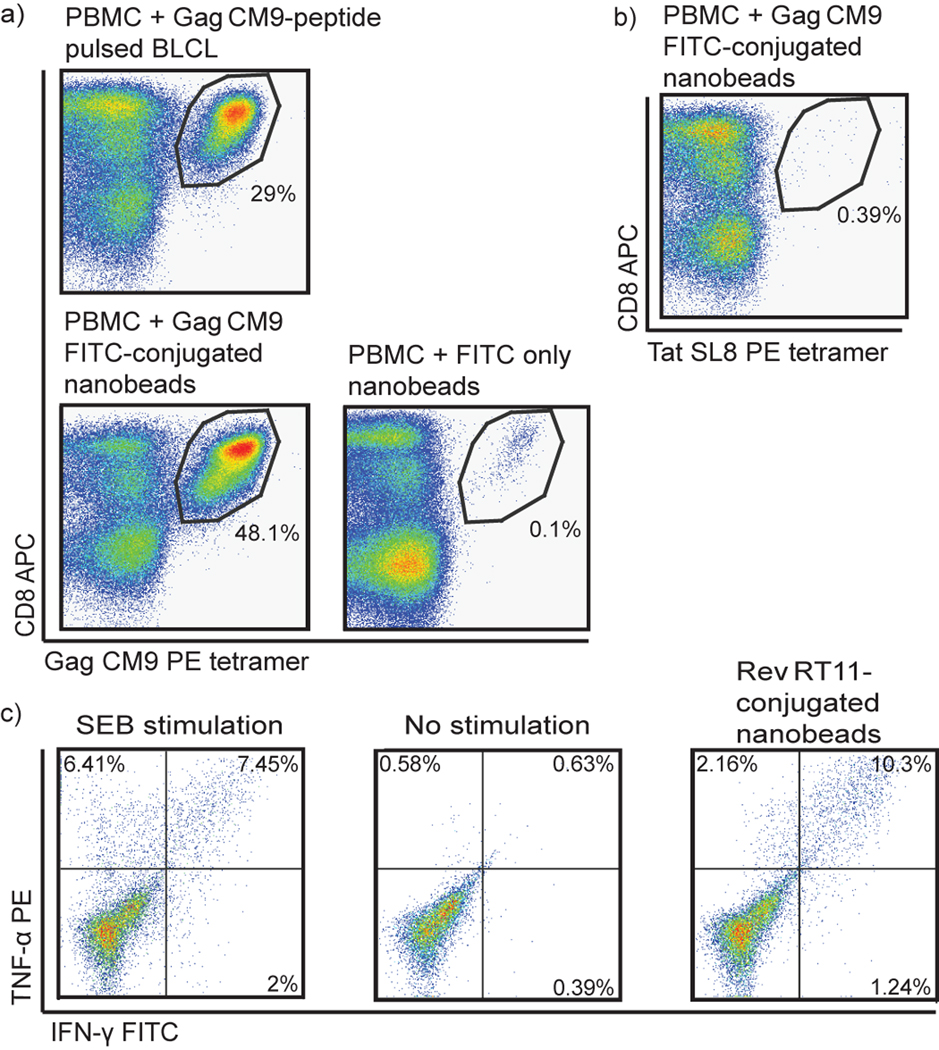

Initially we tested the in vitro immunogenicity of 50 nm carbon-based nanobeads to expand SIV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. We conjugated several peptides overnight to the nanobeads by avidin-biotin conjugation. We isolated PBMC from blood of an SIV-infected rhesus macaque and stimulated the PBMC with a CD8 or CD4 SIV epitope bound to nanobeads for one week. SIV peptide-conjugated nanobeads expanded both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in vitro (Figure 2). Gag CM9-conjugated nanobeads stimulated expansion of Gag CM9-specific CD8+ T cells as well, if not better, than PBMC stimulated with Gag CM9-pulsed B lymphoblastoid cell lines (BLCL) (Figure 2a). Uncoated nanobeads did not induce epitope-specific expansion: nanobeads with only avidin-FITC and no peptide failed to induce Gag CM9-specific expansion (Figure 2a). Additionally, Gag CM9-conjugated nanobeads stimulated expansion of only Gag CM9-specific CD8+ T cells: PBMC stimulated with Gag CM9-conjugated nanobeads were stained with an irrelevant tetramer for Tat SL8 and showed no non-specific CD8+ T cell expansion (Figure 2b). MHC class II DPB1*06-restricted Rev RT11-conjugated nanobeads stimulated expansion of Rev RT11-specific CD4+ T cells from an infected animal known to make this CD4+ T cell response (Figure 2c). Attempts to stimulate naïve SIV-specific T cells from uninfected animals using our in vitro assay were unsuccessful, most likely due to the low frequency of SIV-specific precursors in uninfected animals (data not shown). We were, therefore, able to expand CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in vitro against SIV epitopes conjugated to nanobeads.

Figure 2. In vitro expansion of SIV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells using peptide-conjugated nanobeads.

Freshly isolated PBMC were stimulated with Gag CM9-pulsed BLCLs, Gag CM9-conjugated nanobeads, or unconjugated nanobeads, and maintained in cell culture media containing IL-7 and IL-2. After one week, cells were stained with Gag CM9 tetramer, CD3, and CD8. Lymphocytes were gated on CD3+ cells (a). The cells from (a) were also stained with an irrelevant tetramer, Tat SL8, CD3, and CD8. Lymphocytes were gated on CD3+ cells (b). Freshly isolated PBMC were stimulated with Rev RT11-conjugated nanobeads and maintained in cell culture media containing IL-7 and IL-2. After one week, cells were harvested, stimulated with either Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), no stimulation, or Rev RT11 peptide and intracellularly stained for IFN-γ and TNF-α. Lymphocytes were gated on CD8−CD4+ cells (c).

Novel, small vaccine vectors failed to elicit SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant SIV epitopes

To induce SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes in vivo, we primed Mamu-A*01+ animals with HBcAg-SIV carrier gene and boosted with either peptide-conjugated nanobeads or peptide-pulsed autologous PBMC (Figure 1, Table 1: Groups 1 and 2). The immunogens used in these vaccine modalities were subdominant Mamu-A*01-restricted CD8 epitopes: Gag LF8, Gag QI9, Env TL9, Pol LV10, and Vif QA9 (Table 2). Dominance hierarchies can be determined based on reproducible immune responses detected in virally-infected animals [42]. Gag CM9- and Tat SL8-specific CD8+ T cell responses are consistently detected in Mamu-A*01+ animals after SIVmac239 infection [40,43,44]; therefore, we considered Gag CM9 and Tat SL8 the classical immunodominant Mamu-A*01-restricted epitopes and the other Mamu-A*01 epitopes (Gag LF8, Gag QI9, Env TL9, Pol LV10, and Vif QA9) were considered subdominant [40,44]. Animals received five doses of HBcAg-SIV carrier gene at least one month apart and two boosts of nanobeads or autologous PBMC each one month apart. Neither vaccine regimen tested elicited significant SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses (data not shown). Only one animal made a transient Vif QA9-specific CD8+ T cell response as measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT. As a positive control for vaccination, between each vaccination and two weeks after the final HBcAg-SIV carrier gene vaccination, we tested PBMC for responses against the first 183 amino acids of recombinant HBcAg. PBMC from all animals secreted IFN-γ in response to recombinant HBcAg peptide (data not shown). Thus, priming with the HBcAg-SIV epitope fusion DNA vaccines and boosting with peptide-conjugated nanobeads or peptide-pulsed autologous PBMC failed to induce significant SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant CD8 epitopes.

Table 1.

Vaccination regimens and groups

| Group | Prime | Boost | Epitopes | Animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HepBcAg | Nanobeads | CD8 | r02072, r04126, rh2150 |

| 2 | HepBcAg | PBMC | CD8 | r01089, r01107, r02022 |

| 3 | EP DNA | Ad5 | CD8 | r03057, r06035, r07010 |

| 4 | Dendritic cells | Nanobeads | CD4 | rh2071, r97005, r04109, r04136, r04137 |

| 5 | Dendritic cells | PBMC | CD4 | r04024, r04069, rh2143 |

| 6 | EP DNA | Ad5 | CD4 | r01071, r05067, r06031 |

Table 2.

SIV-specific CD8 epitopes used for vaccination

| Protein | Minimal Optimal | Amino acid position | Amino acid sequence | MHC-I restriction | IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag p2sp | LF8 | 372–379 | LAPVPIPF | Mamu-A*01 | 29a |

| Gag p27CA | QI9 | 254–262 | QNPIPVGNI | Mamu-A*01 | 196a |

| Env | TL9 | 620–628 | TVPWPNASL | Mamu-A*01 | 20a |

| Pol p10PRO | LV10 | 106–115 | LGPHYTPKIV | Mamu-A*01 | 3a |

| Vif | QA9 | 144–152 | QVPSLQYLA | Mamu-A*01 | 141a |

| Gag p27CA | CM9 | 181–189 | CTPYDINQM | Mamu-A*01 | 22b |

Novel, small vaccine vectors fail to elicit SIV-specific CD4+ T cells against SIV epitopes

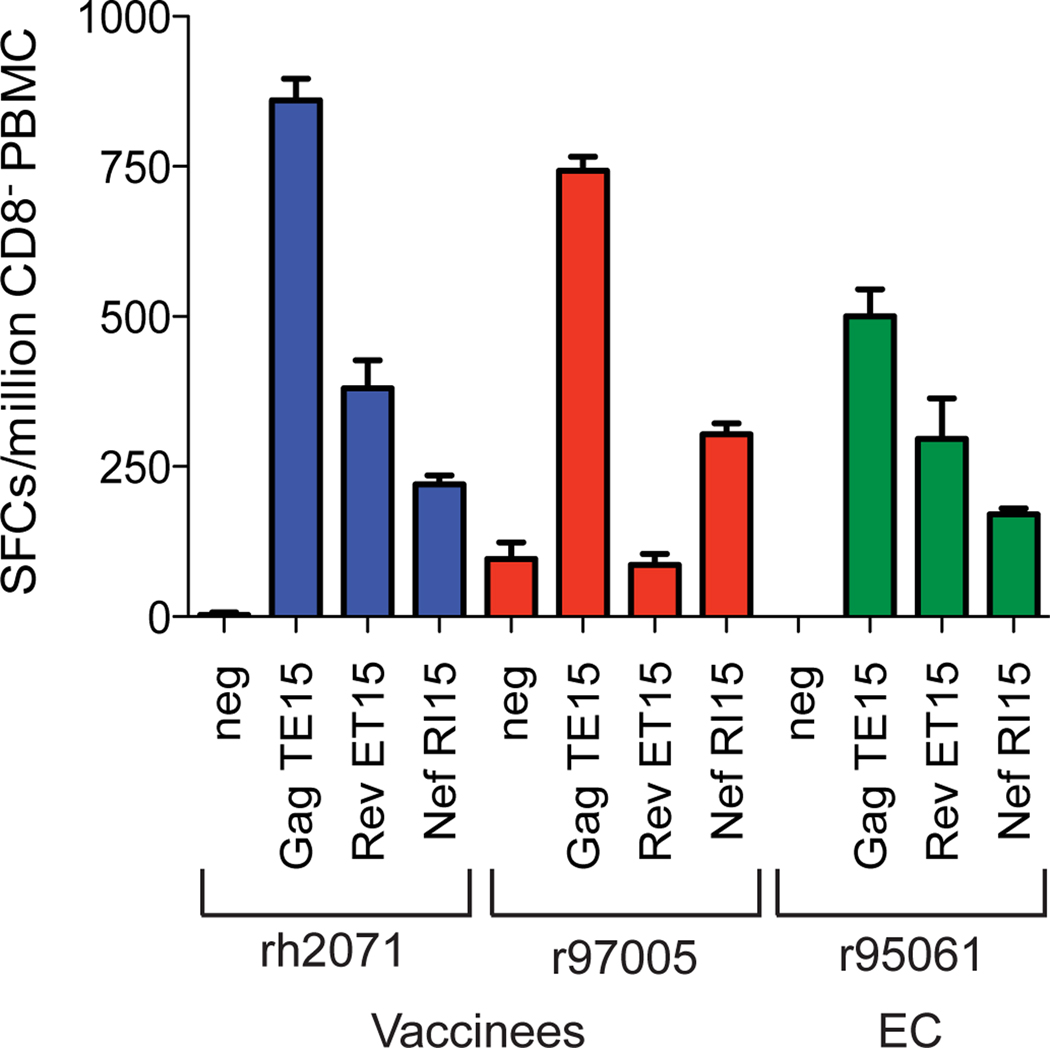

We next tested our ability to induce SIV-specific CD4+ T cells in vivo. We initially vaccinated two Mamu-A*01+, -DRB*w606+ animals with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with Gag TE15, Rev ET15, and Nef RI15 and after several months boosted these animals with Gag TE15-, Rev ET15-, and Nef RI15-conjugated nanobeads (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 3). Both of the vaccinated animals, rh2071 and r97005, made high frequency epitope-specific CD4+ T cell responses eight weeks post-nanobead boost (Figure 3). These responses were comparable to those from an EC, r95061, who has controlled viral replication to undetectable levels throughout the chronic phase of infection and makes the most robust SIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses in our cohort. Animal r97005 did not make a Rev ET15-specific CD4+ T cell response because that animal is Mamu-DPB1*06−. We, therefore, primed an additional six Mamu-DRB*w606+ animals with autologous peptide-pulsed DCs. Three animals were then boosted with peptide-conjugated nanobeads and the other three animals were boosted with autologous peptide-pulsed PBMC (Figure 1, Table 1: Groups 4 and 5). The immunogens used in these vaccine modalities were Mamu-DRB*w606-restricted CD4 epitopes: Gag TE15, Gag RE15, and Nef RI15 (Table 3) [13]. In contrast with our preliminary results, vaccinated animals only made small, transient epitope-specific CD4+ T cell responses (data not shown). Though effective in two of the eight vaccinated animals, these vaccine modalities inconsistently elicited SIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses.

Table 3.

SIV-specific CD4 epitopes used for vaccination

| Protein | Reactive 15mer | Amino acid position | Amino acid sequence | MHC-II restriction | Core Peptide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag p17MA | TE15 | 97–111 | TEEEAKQIVQRHLVVE | Mamu-DRB*w606 | QE10 |

| Gag p7NC | RE15 | 385–399 | RGPRKPIKCWNCGKE | Mamu-DRB*w606 | not mapped |

| Nef | RI15 | 138–152 | RHRILDIYLFKEEGI | Mamu-DRB*w*606 | IG11 |

| Rev | ET15 | 9–23 | ELRKRLRLIHLLHQT | Mamu-DPB1*06 | RT11 |

| Gag p27CA | CD15 | 181–195 | CTPYDINQMLNCVGD | Mamu-DRB*w2104 | YV10 |

Figure 3. Expansion of SIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses after DC/nanobead vaccination.

CD8+ cell-depleted IFN-γ ELISPOT of ex vivo responses specific for Gag TE15, Rev ET15, and Nef RI15 eight weeks post-nanobead boost. The CD4+ T cell response from animal r95061 was shown for comparison as this animal is an elite controller and has maintained undetectable viral loads for over five years.

Electroporated DNA + pIL-12 priming followed by rAd5 boosting elicits SIV-specific CD4+ T cells, but few SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes

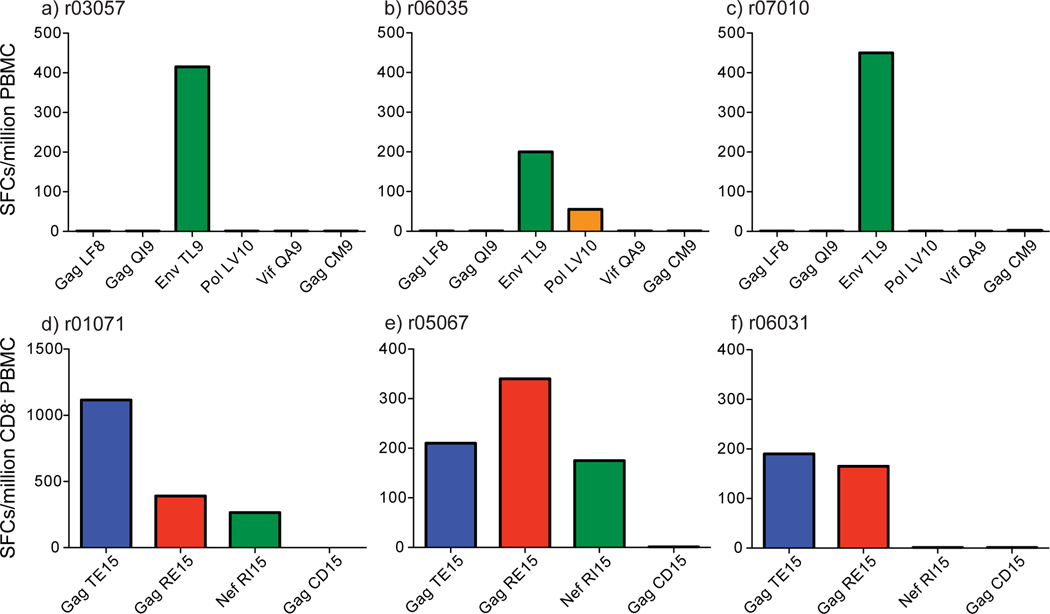

Previous studies have shown enhanced immunogenicity using electroporated DNA (EP DNA) and pIL-12 [45–53]. In order to successfully elicit CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cells through vaccination, we separately inserted the Mamu-A*01-restricted subdominant CD8 epitopes (Table 2) and Mamu-DRB*w606-restricted CD4 epitopes (Table 3) into two well-tested vectors: DNA and recombinant Adenovirus 5 (rAd5) (Groups 3 and 6). Two weeks after the EP DNA + pIL-12 vaccinations with subdominant CD8 epitopes, two of the three animals made low frequency IFN-γ-secreting Env TL9-specific CD8+ T cell responses (data not shown). After the Ad5 boost, all three animals made high frequency Env TL9-specific CD8+ T cell responses (Figure 4a–c). One animal, r06035, also made a detectable Pol LV10-specific CD8+ T cell response.

Figure 4. IFN-γ ELISPOT responses two weeks post-DNA/Ad5 vaccination.

Two weeks post-DNA/Ad5 vaccination whole PBMC or CD8-depleted PBMC IFN-γ responses were measured to each epitope included in the vaccine regimens. Animals vaccinated with DNA/Ad5 vaccines encoding the five subdominant Mamu-A*01-restricted CD8 epitopes made one or two SIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses against the vaccinated epitopes as measured by whole PBMC IFN-γ ELISPOT (a–c). CD8-vaccinated animals did not make CD8+ T cell responses to a control epitope excluded from the vaccines, Mamu-A*01-restricted Gag CM9. Animals vaccinated with DNA/Ad5 vaccines encoding the three Mamu-DRB*w606-restricted CD4 epitopes made two or three SIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses against the vaccinated epitopes as measured by CD8-depleted PBMC IFN-γ ELISPOT (d–f). CD4-vaccinated animals did not make CD4+ T cell responses to a control epitope excluded from the vaccine, Mamu-DRB*w2104-restricted Gag CD15.

All three of the animals vaccinated with CD4 epitopes by EP DNA + pIL-12 priming and Ad5 boosting made at least two epitope-specific CD4+ T cell responses (Figure 4d–f). Two of the three animals made responses to all three CD4 epitopes included in the vaccine inserts. These responses were smaller, but detectable even after EP DNA priming (data not shown). Administering DNA with pIL-12 via electroporation followed by a rAd5 boost elicits robust epitope-specific CD4+ T cell responses. This vaccination regimen was the most immunogenic regimen we tested for eliciting either subdominant CD8+ or CD4+ T cell responses; however, this regimen induced few subdominant epitope-specific CD8+ T cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to elicit SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cells against SIV epitopes using both novel and traditional vectors. The novel, small vaccine vectors failed to induce robust, consistent SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes. They also failed to consistently induce epitope-specific CD4+ T cells. The more traditional DNA prime/rAd5 boost regimen successfully elicited SIV-specific CD4+ T cells against at least two of the three vaccinated epitopes in all three tested animals. Though this vaccination regimen induced one high frequency SIV-specific CD8+ T cell response against a subdominant epitope, it only elicited CD8+ T cell responses against two out of the five subdominant epitopes. Even though novel and traditional vaccine vectors were previously shown to effectively induce CD8+ T cell responses against immunodominant epitopes in mice and/or rhesus macaques [19–21,23,34], we still did not adequately elicit CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes even in the absence of immunodominant epitopes.

Although high frequency, robust and persistent HIV/SIV-specific CD4+ T cells are seen in human and rhesus macaque ECs [13,14], they are also the preferential targets of HIV/SIV [54,55]. During the acute phase of infection, CD4+ memory T cells are rapidly depleted, particularly in the gut associated lymphoid tissue [56–59]. It is difficult to differentiate whether the presence of virus-specific CD4+ T cells actively contributes to control of viral replication or is due to low levels of viral replication. Inducing CD4+ T cells by vaccination could, therefore, increase the number of available targets for HIV/SIV replication [60]. The role of HIV/SIV-specific CD4+ T cells in infection should, therefore, be further elucidated. It is important to determine whether vaccine-induced CD4+ T cells will blunt or intensify viral replication.

We induced epitope-specific CD4+ T cells using peptides that were 15 amino acids in length rather than the core peptide. Though all five of the subdominant CD8 epitopes have high affinity for Mamu-A*01, we failed to induce SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against several subdominant CD8 epitopes. For the CD8 vaccinations we used the minimal optimal peptide ranging from eight to ten amino acids in length. Using short minimal optimal peptides for vaccination may not be the most favorable strategy. Including flanking amino acids in the vaccination inserts might be more physiologically relevant and thus lead to more efficient peptide processing and loading of MHC class I molecules [61,62].

Several lines of evidence suggest that increasing HIV/SIV-specific CD8+ T cell breadth may contribute to improved control of viral replication [63–66]. Additionally, HIV is highly variable: its reverse transcriptase lacks a proofreading mechanism, which results in at least one mutation per replication cycle. Additionally, HIV mutates specific amino acid residues to escape from HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses, antibodies, and antiretroviral drugs. It is, therefore, critical for an effective HIV vaccine to elicit several HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses prior to infection, especially CD8+ T cells against naturally subdominant epitopes. Thus, finding a vector capable of eliciting virus-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes is of utmost importance.

Electroporating DNA with pIL-12 and boosting with adenovirus elicits robust, high frequency SIV-specific CD4+ T cells against all SIV epitopes tested. This and novel, small vectors, however, failed to induce several subdominant SIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Using longer peptide sequences might improve immunogenicity and could be considered in future vaccine studies. Additionally, CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant epitopes may be more difficult to generate than CD8+ T cell responses against immunodominant epitopes. This may be due to the relatively low precursor frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for subdominant epitopes, the limited T cell receptor clonal repertoire of CD8+ T cells specific for subdominant epitopes [67], or additional unknown biological restrictions. Being able to elicit SIV-specific CD8+ T cells against subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cells either together or alone, however, may test critical outstanding questions in HIV research and potentially improve vaccine efficacy.

Highlights.

In this study, we attempt to elicit CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cell responses.

We conclude that it is relatively straightforward to elicit CD4+ T cell responses against SIV epitopes.

Eliciting CD8+ T cell responses against subdominant SIV epitopes is far more difficult than previously believed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grants R21 AI077472, R01 AI076114, R01 AI049120, R24 RR015371, and R24 RR016038 and in part by grant R51 RR000167 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) awarded to the WNPRC, University of Wisconsin-Madison. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: IL-2, human (item no. 136) from Hoffman-La Roche.

We gratefully acknowledge Barbara K. Felber, Ernesto T.A. Marques, and J. Thomas August for kindly providing the 8L-CMVhuLAMPkan vector; and Barbara K. Felber and George N. Pavlakis for the rhesus IL-12 plasmid (AG157). We would also like to acknowledge Drew Hannaman and Barry Ellefsen at Ichor Medical Systems, Inc for use of the electroporation device. The authors also would like to acknowledge Jessica Furlott for technical assistance; and Chrystal Glidden, Gretta Borchardt, and Debra Fisk for MHC typing of animals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen W, Antón LC, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Dissecting the multifactorial causes of immunodominance in class I-restricted T cell responses to viruses. Immunity. 2000;12:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen ZW, Craiu A, Shen L, Kuroda MJ, Iroku UC, Watkins DI, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus evades a dominant epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response through a mutation resulting in the accelerated dissociation of viral peptide and MHC class I. J Immunol. 2000;164:6474–6479. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallimore A, Dumrese T, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM, Rammensee HG. Protective immunity does not correlate with the hierarchy of virus-specific cytotoxic T cell responses to naturally processed peptides. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1647–1657. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmowski MJ, Choi EM, Hermans IF, Gilbert SC, Chen JL, Gileadi U, et al. Competition between CTL narrows the immune response induced by prime-boost vaccination protocols. J Immunol. 2002;168:4391–4398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez F, Harkins S, Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Immunodominance in virus-induced CD8(+) T-cell responses is dramatically modified by DNA immunization and is regulated by gamma interferon. J Virol. 2002;76:4251–4259. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4251-4259.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altfeld M, Rosenberg ES. The role of CD4(+) T helper cells in the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to HIV-1. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bevan MJ. Helping the CD8(+) T-cell response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:595–602. doi: 10.1038/nri1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalams SA, Walker BD. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2199–2204. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matloubian M, Concepcion RJ, Ahmed R. CD4+ T cells are required to sustain CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Virol. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boaz MJ, Waters A, Murad S, Easterbrook PJ, Vyakarnam A. Presence of HIV-1 Gag-specific IFN-gamma+IL-2+ and CD28+IL-2+ CD4 T cell responses is associated with nonprogression in HIV-1 infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:6376–6385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedrich TC, Valentine LE, Yant LJ, Rakasz EG, Piaskowski SM, Furlott JR, et al. Subdominant CD8+ T-cell responses are involved in durable control of AIDS virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:3465–3476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giraldo-Vela JP, Bean AT, Rudersdorf R, Wallace LT, Loffredo JT, Erickson P, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4+ T cells from successful vaccinees target the SIV Gag capsid. Immunogenetics. 2010;62:701–707. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraldo-Vela JP, Rudersdorf R, Chung C, Qi Y, Wallace LT, Bimber B, et al. The major histocompatibility complex class II alleles Mamu-DRB1*1003 and - DRB1*0306 are enriched in a cohort of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaque elite controllers. J Virol. 2008;82:859–870. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01816-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenberg ES, Billingsley JM, Caliendo AM, Boswell SL, Sax PE, Kalams SA, et al. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson NA, Keele BF, Reed JS, Piaskowski SM, MacNair CE, Bett AJ, et al. Vaccine-induced cellular responses control simian immunodeficiency virus replication after heterologous challenge. J Virol. 2009;83:6508–6521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chea S, Dale CJ, De Rose R, Ramshaw IA, Kent SJ. Enhanced cellular immunity in macaques following a novel peptide immunotherapy. J Virol. 2005;79:3748–3757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3748-3757.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu W, Arraes LC, Ferreira WT, Andrieu JM. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 2004;10:1359–1365. doi: 10.1038/nm1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu W, Wu X, Lu Y, Guo W, Andrieu JM. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for simian AIDS. Nat Med. 2003;9:27–32. doi: 10.1038/nm806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller DH, Shipley T, Allen TM, Fuller JT, Wu MS, Horton H, et al. Immunogenicity of hybrid DNA vaccines expressing hepatitis B core particles carrying human and simian immunodeficiency virus epitopes in mice and rhesus macaques. Virology. 2007;364:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fifis T, Gamvrellis A, Crimeen-Irwin B, Pietersz GA, Li J, Mottram PL, et al. Size-dependent immunogenicity: therapeutic and protective properties of nano-vaccines against tumors. J Immunol. 2004;173:3148–3154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fifis T, Mottram P, Bogdanoska V, Hanley J, Plebanski M. Short peptide sequences containing MHC class I and/or class II epitopes linked to nano-beads induce strong immunity and inhibition of growth of antigen-specific tumour challenge in mice. Vaccine. 2004;23:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minigo G, Scholzen A, Tang CK, Hanley JC, Kalkanidis M, Pietersz GA, et al. Poly-L-lysine-coated nanoparticles: a potent delivery system to enhance DNA vaccine efficacy. Vaccine. 2007;25:1316–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber HA, Prechl J, Jiang H, Zozulya A, Fabry Z, Denes F, et al. Using carbon magnetic nanoparticles to target, track, and manipulate dendritic cells. J Immunol Methods. 2010;356:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalkanidis M, Pietersz GA, Xiang SD, Mottram PL, Crimeen-Irwin B, Ardipradja K, et al. Methods for nano-particle based vaccine formulation and evaluation of their immunogenicity. Methods. 2006;40:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheerlinck JP, Gloster S, Gamvrellis A, Mottram PL, Plebanski M. Systemic immune responses in sheep, induced by a novel nano-bead adjuvant. Vaccine. 2006;24:1124–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaizu M, Borchardt GJ, Glidden CE, Fisk DL, Loffredo JT, Watkins DI, et al. Molecular typing of major histocompatibility complex class I alleles in the Indian rhesus macaque which restrict SIV CD8+ T cell epitopes. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:693–703. doi: 10.1007/s00251-007-0233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loffredo JT, Maxwell J, Qi Y, Glidden CE, Borchardt GJ, Soma T, et al. Mamu-B*08-positive macaques control simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J Virol. 2007;81:8827–8832. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ignatius R, Tenner-Racz K, Messmer D, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Luckay A, et al. Increased macrophage infection upon subcutaneous inoculation of rhesus macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus-loaded dendritic cells or T cells but not with cell-free virus. J Virol. 2002;76:9787–9797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9787-9797.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obermaier B, Dauer M, Herten J, Schad K, Endres S, Eigler A. Development of a new protocol for 2-day generation of mature dendritic cells from human monocytes. Biological procedures online. 2003;5:197–203. doi: 10.1251/bpo62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pertmer TM, Eisenbraun MD, McCabe D, Prayaga SK, Fuller DH, Haynes JR. Gene gun-based nucleic acid immunization: elicitation of humoral and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses following epidermal delivery of nanogram quantities of DNA. Vaccine. 1995;13:1427–1430. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00069-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denes F, Manolache S, Ma Y, Shamamian V, Ravel B, Prokes S. Dense medium plasma synthesis of carbon/iron-based magnetic nanoparticle system. Journal of Applied Physics. 2003;94:3498–3508. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulkarni V, Jalah R, Ganneru B, Bergamaschi C, Alicea C, von Gegerfelt A, et al. Comparison of immune responses generated by optimized DNA vaccination against SIV antigens in mice and macaques. Vaccine. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valentin A, Chikhlikar P, Patel V, Rosati M, Maciel M, Chang KH, et al. Comparison of DNA vaccines producing HIV-1 Gag and LAMP/Gag chimera in rhesus macaques reveals antigen-specific T-cell responses with distinct phenotypes. Vaccine. 2009;27:4840–4849. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cristillo AD, Weiss D, Hudacik L, Restrepo S, Galmin L, Suschak J, et al. Persistent antibody and T cell responses induced by HIV-1 DNA vaccine delivered by electroporation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dolter KE, Evans CF, Ellefsen B, Song J, Boente-Carrera M, Vittorino R, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, biodistribution and persistence of ADVAX, a prophylactic DNA vaccine for HIV-1, delivered by in vivo electroporation. Vaccine. 2011;29:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luxembourg A, Hannaman D, Ellefsen B, Bernard R. Enhancement of immune responses to an HBV DNA vaccine by electroporation. Vaccine. 2006;24:4490–4493. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer JD, Robinson TM, Kutzler MA, Parkinson R, Calarota SA, Sidhu MK, et al. SIV DNA vaccine co-administered with IL-12 expression plasmid enhances CD8 SIV cellular immune responses in cynomolgus macaques. J Med Primatol. 2005;34:262–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson RD, Haskell RE, Xia H, Roessler BJ, Davidson BL. A simple method for the rapid generation of recombinant adenovirus vectors. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1034–1038. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loffredo JT, Sidney J, Wojewoda C, Dodds E, Reynolds MR, Napoé G, et al. Identification of seventeen new simian immunodeficiency virus-derived CD8+ T cell epitopes restricted by the high frequency molecule, Mamu-A*02, and potential escape from CTL recognition. J Immunol. 2004;173:5064–5076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen TM, Mothé BR, Sidney J, Jing P, Dzuris JL, Liebl ME, et al. CD8(+) lymphocytes from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques recognize 14 different epitopes bound by the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule mamu-A*01: implications for vaccine design and testing. J Virol. 2001;75:738–749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.738-749.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson NA, Reed J, Napoe GS, Piaskowski S, Szymanski A, Furlott J, et al. Vaccine-induced cellular immune responses reduce plasma viral concentrations after repeated low-dose challenge with pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239. J Virol. 2006;80:5875–5885. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00171-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yewdell JW. Confronting complexity: real-world immunodominance in antiviral CD8+ T cell responses. Immunity. 2006;25:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedrich TC, Dodds EJ, Yant LJ, Vojnov L, Rudersdorf R, Cullen C, et al. Reversion of CTL escape-variant immunodeficiency viruses in vivo. Nat Med. 2004;10:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mothé BR, Horton H, Carter DK, Allen TM, Liebl ME, Skinner P, et al. Dominance of CD8 responses specific for epitopes bound by a single major histocompatibility complex class I molecule during the acute phase of viral infection. J Virol. 2002;76:875–884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.875-884.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirao LA, Wu L, Khan AS, Hokey DA, Yan J, Dai A, et al. Combined effects of IL-12 and electroporation enhances the potency of DNA vaccination in macaques. Vaccine. 2008;26:3112–3120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luckay A, Sidhu MK, Kjeken R, Megati S, Chong SY, Roopchand V, et al. Effect of plasmid DNA vaccine design and in vivo electroporation on the resulting vaccine-specific immune responses in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 2007;81:5257–5269. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otten G, Schaefer M, Doe B, Liu H, Srivastava I, zur Megede J, et al. Enhancement of DNA vaccine potency in rhesus macaques by electroporation. Vaccine. 2004;22:2489–2493. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Otten GR, Schaefer M, Doe B, Liu H, Megede JZ, Donnelly J, et al. Potent immunogenicity of an HIV-1 gag-pol fusion DNA vaccine delivered by in vivo electroporation. Vaccine. 2006;24:4503–4509. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosati M, von Gegerfelt A, Roth P, Alicea C, Valentin A, Robert-Guroff M, et al. DNA vaccines expressing different forms of simian immunodeficiency virus antigens decrease viremia upon SIVmac251 challenge. J Virol. 2005;79:8480–8492. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8480-8492.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schadeck EB, Sidhu M, Egan MA, Chong SY, Piacente P, Masood A, et al. A dose sparing effect by plasmid encoded IL-12 adjuvant on a SIVgag-plasmid DNA vaccine in rhesus macaques. Vaccine. 2006;24:4677–4687. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winstone N, Wilson AJ, Morrow G, Boggiano C, Chiuchiolo MJ, Lopez M, et al. Enhanced control of pathogenic SIVmac239 replication in macaques immunized with a plasmid IL12 and a DNA prime, viral vector boost vaccine regimen. J Virol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JVI.05060-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu R, Megati S, Roopchand V, Luckay A, Masood A, Garcia-Hand D, et al. Comparative ability of various plasmid-based cytokines and chemokines to adjuvant the activity of HIV plasmid DNA vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26:4819–4829. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, Nolan E, Kreitschitz S, Rabussay DP. Enhanced delivery of naked DNA to the skin by non-invasive in vivo electroporation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douek DC, Brenchley JM, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Okamoto Y, et al. HIV preferentially infects HIV-specific CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2002;417:95–98. doi: 10.1038/417095a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veazey RS, Tham IC, Mansfield KG, DeMaria M, Forand AE, Shvetz DE, et al. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4(+) T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:57–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.57-64.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brenchley JM, Schacker TW, Ruff LE, Price DA, Taylor JH, Beilman GJ, et al. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:749–759. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, et al. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;434:1148–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mattapallil JJ, Douek DC, Hill B, Nishimura Y, Martin M, Roederer M. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature. 2005;434:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature03501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, Knight HL, et al. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 1998;280:427–431. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brenchley JM, Ruff LE, Casazza JP, Koup RA, Price DA, Douek DC. Preferential infection shortens the life span of human immunodeficiency virus-specific CD4+ T cells in vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:6801–6809. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00070-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Le Gall S, Stamegna P, Walker BD. Portable flanking sequences modulate CTL epitope processing. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3563–3575. doi: 10.1172/JCI32047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yewdell JW. The seven dirty little secrets of major histocompatibility complex class I antigen processing. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiepiela P, Ngumbela K, Thobakgale C, Ramduth D, Honeyborne I, Moodley E, et al. CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat Med. 2007;13:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nm1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, O'Brien KL, Lynch DM, Simmons NL, La Porte A, Riggs AM, et al. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2009;457:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature07469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loffredo JT, Bean AT, Beal DR, León EJ, May GE, Piaskowski SM, et al. Patterns of CD8+ immunodominance may influence the ability of Mamu-B*08- positive macaques to naturally control simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J Virol. 2008;82:1723–1738. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02084-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martins MA, Wilson NA, Reed JS, Ahn CD, Klimentidis YC, Allison DB, et al. T-cell correlates of vaccine efficacy after a heterologous simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. J Virol. 2010;84:4352–4365. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02365-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manuel ER, Charini WA, Sen P, Peyerl FW, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, et al. Contribution of T-cell receptor repertoire breadth to the dominance of epitope-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses. J Virol. 2006;80:12032–12040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01479-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]