Abstract

Background

Cocaine dependence is associated with high relapse rates but few biological markers associated with relapse outcomes have been identified. Extending preclinical research showing a role for central Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) in cocaine seeking, we examined whether serum BDNF is altered in abstinent, early recovering, cocaine-dependent individuals and if it is predictive of subsequent relapse risk.

Methods

Serum samples were collected across three consecutive mornings from 35 treatment-engaged, 3 week abstinent cocaine-dependent inpatients (17M/18F) and 34 demographically matched hospitalized healthy control participants (17M/17F). Cocaine dependent individuals were prospectively followed on days 14, 30 and 90 post-treatment discharge to assess cocaine relapse outcomes. Time to cocaine relapse, number of days of cocaine use (frequency), and amount of cocaine use (quantity) were the main outcome measures.

Results

High correlations in serum BDNF across days indicated reliable and stable serum BDNF measurements. Significantly higher mean serum BDNF levels were observed for the cocaine-dependent patients compared to healthy control participants (p<.001). Higher serum BDNF levels predicted shorter subsequent time to cocaine relapse (hazard ratio: HR: 1.09, p<.05), greater number of days (p<.05) and higher total amounts of cocaine used (p = .05).

Conclusions

High serum BDNF levels in recovering cocaine-dependent individuals are predictive of future cocaine relapse outcomes and may represent a clinically relevant marker of relapse risk. These data suggest that serum BDNF levels may provide an indication of relapse risk during early recovery from cocaine dependence.

Keywords: BDNF, cocaine dependence, cocaine relapse, treatment outcome

Cocaine dependence is a chronic relapsing disorder in which few biological markers relevant in the recovery process have been identified (1). As cocaine dependence has been well-characterized by robust relapse-related alterations in peripheral and central stress and reward systems (2, 3), changes in biological markers such as BDNF, may reflect chronic cocaine-induced allostatic load (4) and represent an important indicator of relapse outcome.

In preclinical research on cocaine addiction, the specific nature of BDNF changes depends on temporal drug use and methodological parameters. In cocaine-experienced animals, exposure to stressful stimuli augments brain mesolimbic BDNF and corticosterone responses following a prolonged but not short, period of cocaine withdrawal (5). These data suggest that abstinence-related adaptations in BDNF expression may contribute to stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Challenge studies in animals manipulating BDNF within brain areas critical for the rewarding effects of cocaine, indicate that increased BDNF levels are integral to cocaine-seeking behaviors, i.e. conditioned place preference, drug taking (self-administration) and relapse (cocaine-primed reinstatement) (6–9). For example, local BDNF injections into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) can potentiate cocaine-seeking following prolonged cocaine abstinence (6) and BDNF infusions into the nucleus accumbens (NAc) during self-administration can facilitate stress-induced drug reinstatement (8). Additionally, a sensitizing regimen or cocaine injections (10) or cocaine self-administration followed by protracted drug withdrawal produces time-dependent increases in BDNF expression in mesocorticolimbic regions (8, 9, 11, 12), indicating that BDNF is temporally regulated by cocaine exposure.

The relationship between central and peripheral BDNF has been examined in animal models with recent studies reporting significant positive correlations between serum, whole blood levels, and brain tissue levels (13, 14). Additional evidence comes from preclinical research indicating that peripheral BDNF administration produces robust cellular and behavioral adaptations in the brain (15). However, no previous research has examined peripheral BDNF during early recovery in cocaine dependent individuals and assessed its role in cocaine relapse risk.

The current study aims to assess serum BDNF levels in abstinent, cocaine-dependent individuals compared to a group of demographically matched healthy controls. We also aim to examine whether potential alterations in serum BDNF levels in cocaine-dependent individuals are predictive of subsequent cocaine relapse outcomes using a prospective clinical outcome design. The primary outcome measures are serum BDNF and cocaine relapse measures of time to cocaine relapse, number of days and amounts of cocaine used during the 90-day follow-up period. Escalation of cocaine used is measured by cumulative increases in average amounts of cocaine used during the follow-up period.

Methods and Materials

Participants

35 treatment-seeking cocaine-dependent (CD) individuals (17M/18F), and 34 demographically matched socially drinking, healthy controls (HC; 17M/17F) were recruited via local newspapers or online advertisements. Presence of current cocaine dependence in the CD group and absence of substance use disorders in the HC group was determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (SCID IV) (16) and regular urine toxicology screens at all assessment appointments. Exclusion criteria for CD patients included DSM-IV dependence for any drug other than cocaine, alcohol or nicotine. Participants with concurrent alcohol and nicotine use disorders were not excluded, due to high rates of alcohol and nicotine comorbidity with cocaine dependence (17). Those who were currently on medications for medical and psychiatric problems and those in need of alcohol detoxification were excluded from the study. A third of the screened CD subjects were eligible. Written informed consent of all participants was obtained. The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine.

Inpatient procedures

CD patients were admitted to the Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit (CNRU) of the Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC) for 4 weeks of inpatient treatment and study participation. The CNRU is a locked treatment facility with no access to alcohol or drugs and limited access to visitors. Drug testing was conducted regularly to ensure abstinence. Nicotine smoking was allowed during 4 smoke breaks per day. Treatment was initiated upon admission and was part of their daily inpatient treatment program. HC participants were tested during a 3-day research stay at the Hospital Research Unit (HRU) of the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI). This ensured that the control subjects were kept in a similar controlled hospital environment to that of the CD participants (e.g., diet, exercise etc.) during the 3 consecutive days over which the blood draws were performed. All participants completed assessments to obtain socio-demographic history, DSM-IV psychiatric diagnoses (16) and estimated IQ using the Shipley Institute of Living Scale (18).

Blood Collection, Serum Separation and BDNF assay

Blood samples were obtained over three consecutive mornings during fasting states, between 8.00–8.30 am, to minimize variance arising from reported circadian variation in BDNF levels (19). Samples from CD participants were obtained 3 weeks after admission to minimize acute cocaine withdrawal effects. Blood from HCs was obtained during their stay on the HRU. Blood was collected in anticoagulant-free tubes (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA). To obtain serum, whole blood samples were coagulated for 30 minutes at room temperature and centrifuged for 10 minutes, 1000 X g.

BDNF concentrations were quantitatively determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions (DuoSet ELISA Development Kit R&D systems; Minneapolis, MN, USA). Samples were diluted 1:50 in sample diluent buffer, assays were performed in 96 well plates, absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a SpectraMax Plus384 plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA), with the correction wavelength set at 540 nm. Measurements were performed in duplicate, averaged to give a value in pg/ml, which was then expressed in ng/ml after correcting for sample dilution. Intra-assay coefficients of variations (CV) were 5.2% and 4.7%; corresponding inter-assay CV were 9.4% and 7.2%. The ELISA plate templates were planned so that all samples (Day 1, Day 2 and Day 3) from a particular participant were run in the same assay. Samples from HC and CD individuals were assayed under blinded conditions.

Prospective Follow-up Interviews to Assess Cocaine Relapse Outcomes

Upon discharge, all CD participants were given appointments for follow-up interviews on day 14, 30 and 90, post-discharge. Substance use was assessed at each appointment by means of urine drug toxicology testing for cocaine metabolites and the Substance Use Calendar (SUC) (20), an instrument that has been validated in drug-abusing samples and widely used in assessing cocaine use outcomes in previous treatment studies (21). Urine and breath alcohol samples were obtained at each appointment. All 35 CD individuals returned for at least one face-to-face follow-up interview, with return rates being 94% at 14 days, 89% at 30 days, and 88% at 90 days. Time to relapse data was available on all 35 CD patients, amount and frequency of cocaine use data was available on 31 of the 35 patients (88%) who were successfully followed for the 90-day period.

To capture both initial lapse (any use) and relapse to regular patterns of cocaine use, relapse was examined both as a dichotomous variable (no use[success] versus any use[failure]) and as continuous measures of drug use (e.g. number of days of use and amounts of use per occasion) during the follow-up. The following cocaine use measures were computed from the follow-up SUC and detection of cocaine metabolite in the urine: (1) time to relapse: the interval to the first day of any cocaine use after discharge from inpatient treatment (success versus failure); (2) quantity: the amount of cocaine used (grams) at each occasion resulting in total amount of cocaine used, and cumulative amounts of cocaine used each week over the 90 days; (3) frequency: the total number of days of cocaine use during the 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

All the statistical evaluations were performed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Independent t-tests or chi-squares were used to assess group differences in baseline cocaine use and demographic variables. Linear Mixed Effect models (LME) (22) were used to assess group differences in BDNF levels across the three days. The between-subjects factor of Group, (HC versus CD) and the within-subjects factor of Day (Day 1, Day 2, Day 3) were the Fixed Effects, and Subjects was the Random Effect. Demographic factors were used as covariates in the case of any significant group variation. Spearman’s Rho was used to assess intra-individual, between-day correlations in BDNF levels and associations between BDNF and clinical descriptive variables.

To assess the specific relationship between serum BDNF and relapse factors, we first assessed whether any demographic, clinical and/or drug use measure contributed to relapse outcomes using Cox proportional hazard regression (23) for time to relapse outcome and standard regression analyses for quantity and frequency of cocaine used. Any significant demographic, clinical or drug use related measure from these analyses were included as covariates in the final Cox regression models to test whether BDNF levels independently predicted subsequent time to relapse (event analysis). Similarly, significant covariates were included in the standard regression analyses conducted to examine if BDNF levels were predictive of total amount in grams of cocaine use (quantity) and number of days of cocaine used (frequency), across the 90 day period.

Results

Demographics and sample characteristics of cocaine-dependent patients and healthy controls

The groups did not differ on demographic measures of age, gender, race, Shipley estimated IQ and on lifetime prevalence of mood disorders, but the CD group comprised significantly more nicotine smokers and those who met criteria for lifetime alcohol dependence or anxiety disorders without post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and sample characteristics in the COC and HC groups

| Subject Variable | COC (N=35) | HC (N=34) |

|---|---|---|

| Age: (years) mean (SD) | 37 (5.9) | 34 (9.19) |

| IQ Shipley: mean (SD) | 105(10.3) | 111 (11.8) |

| Gender: male; number (%) | 17 (49%) | 17 (50%) |

| Race | ||

| African American (number %) | 19 (54% ) | 11 (32% ) |

| Caucasian (number %) | 13 (37% ) | 19 (56% ) |

| Hispanic (number %) | 2 (6% ) | 4 (12% ) |

| Cocaine Use: mean (SD) | ||

| Age first used cocaine | 19.6 (4.3) | - |

| Number of years of Cocaine Use | 9.4 (6.9) | - |

| Number of days cocaine used in the last 30 days | 20.7(9.5) | - |

| Total amount of cocaine (grams) used in the last 30 days | 39.8 (40.9) | - |

| Number of Smokers** | 29 (83%) | 4 (12%) |

| Lifetime Alcohol Dependence** | 14 (40%) | 0 |

| Lifetime Mood Disorders | 7 (20%) | 2 (6%) |

| Lifetime Anxiety Disorders without PTSD* | 4 (11%) | 0 |

| Lifetime prevalence of PTSD | 10 (29%) | 4 (12%) |

Note:

p<0.05;

p<0.001;

Stability of serum BDNF levels

No significant day-to-day difference in the mean serum BDNF levels were observed across the entire sample (F2,117 = 1.14; p = 0.32). Significant correlations were obtained between all three days for all subject participants: between Day 1 and Day 2 (n = 69, r = 0.71, p = 0.002); between Day 1 and Day 3 (n= 69, r = 0.69, p = 0.003) and between Day 2 and Day 3 (n = 69, r = 0.74, p = 0.006). Similar correlations were also observed in the separate groups.

Group comparison of serum BNDF levels in the cocaine-dependent and healthy control groups

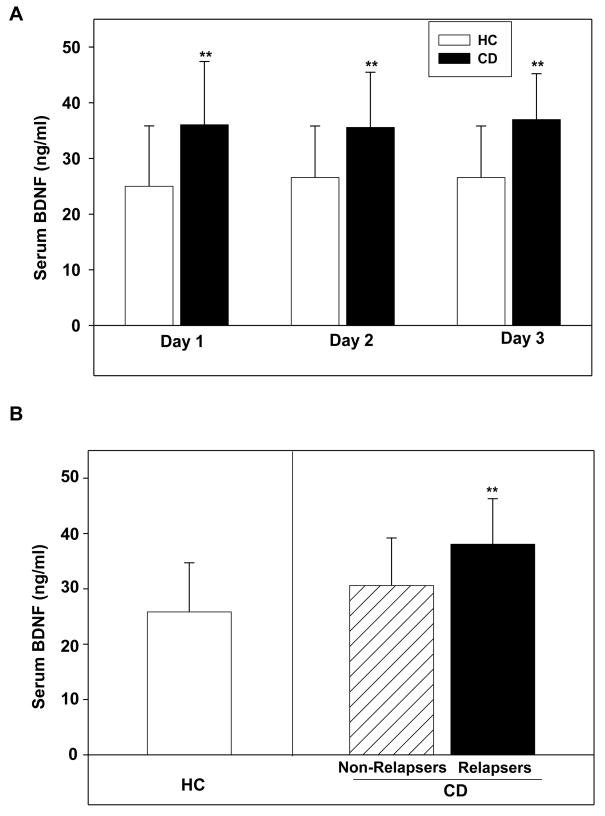

A main effect of group demonstrated that CD patients had significantly higher serum BDNF levels compared with HC individuals (F1,67 = 20.31, p < 0.0001) and no significant effects of repeated sampling across days or group X day interactions (Figure 1A). Group differences were substantial, with the cocaine-dependent group means being 28–56 % higher than the control group. When individual values were collapsed across days, the HC and CD group means were 25.8 ± 8.9 ng/ml versus 36 ± 9.2 ng/ml, respectively; an elevation of 40% in the CD group compared to the HC group. Moreover, this group effect remained significant even when smoking status, lifetime anxiety disorders without/with PTSD were included as covariates in the LME analyses (F1,62 = 4.35, p < 0.04). Serum BDNF did not correlate significantly with age, IQ, smoking status and prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders (with and without PTSD).

Figure 1.

(A). Serum BDNF concentrations (ng/ml, mean± sd) measured in healthy control (HC; N=34 subjects) and cocaine-dependent individuals (N=35 subjects; p < 0.001) (B). Serum BDNF concentrations (ng/ml, mean± sd) measured in the non-relapsing (N=12) and relapsing (N=23) cocaine-dependent (CD) individuals and healthy control (HC; N=34) individuals. The relapser-CD group had significantly higher serum BDNF than the HCs (p < 0.001) and the non-relapsed CDs (p = 0.04). Note: **p <.05.

Association of serum BDNF with pre-admission clinical descriptive variables in the cocaine-dependent group

No significant associations were observed between mean serum BDNF levels and the total quantity (in grams) and frequency (number of days) of cocaine use in the previous 90 days prior to inpatient admission. In addition, there was no significant association between BDNF levels and the age of onset of cocaine use, and years of cocaine use.

Relapse rates and serum BDNF levels in the relapser and non-relapser cocaine- dependent groups

On the basis of urine toxicology screens and self-report data, two-thirds of the CD participants (23/35 [66%]) had returned to cocaine use by the end of the 90-day period. Urine and toxicology results and self-report data were concordant for all 35 cocaine-dependent subjects. Group mean serum BDNF levels were 38.1 ± 8.2 ng/ml versus 30.6 ± 8.6 ng/ml, in the relapsing and non-relapsing CD groups respectively, when individual values were collapsed across days. A main effect of group (F2,68 = 12.1, p < 0.001) demonstrated that the relapsed cocaine-dependent patients had significantly higher serum BDNF levels compared with healthy control (p<.0001) and the non-relapser cocaine-dependent groups (p=.04; Figure 1B).

Demographic and cocaine use associations with relapse outcomes

Demographic measures of age, IQ, employment status, race, gender, smoking, lifetime history of major depression, anxiety and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were not with cocaine relapse outcomes. Demographic measures were not associated with cocaine relapse outcomes in relapsers versus non-relapsers. Relapse outcomes in relapsers versus non-relapsers were not associated with number of previous quit attempts prior to study enrollment. Additionally, the amount and frequency of cocaine use for the 90-day period prior to admission, as well as years of cocaine use, were not predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. However, lifetime alcohol dependence history was significantly predictive of a lower likelihood of relapse (X2=3.64; p = 0.056; hazard ratio, 0.401; 95% confidence interval, 0.16–1.02).

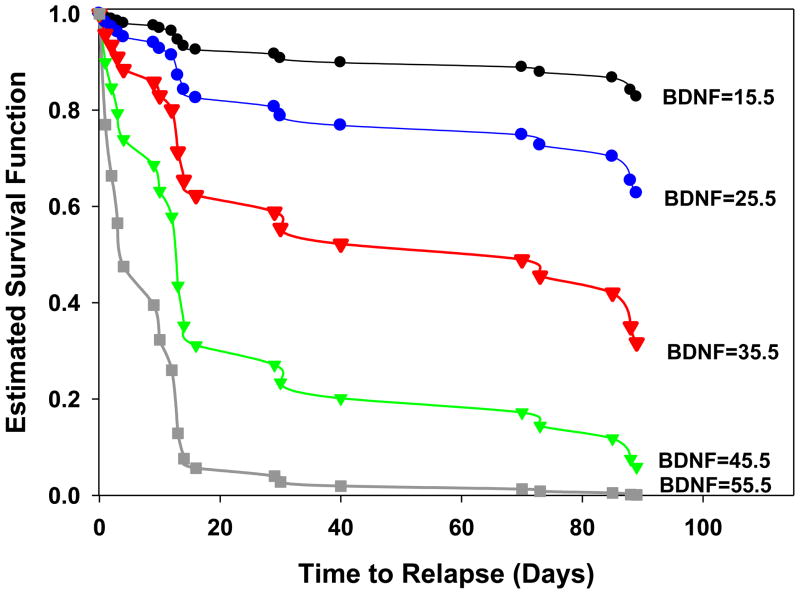

BDNF levels and time to cocaine relapse

Results from Cox proportional hazards regression analyses indicated that greater serum BDNF levels were significantly predictive of a shorter time to cocaine relapse following inpatient treatment. For each additional unit increase in serum BDNF level, there was a 9% increase in the likelihood of cocaine relapse during the 90-day follow-up. Serum BDNF significantly predicted shorter time to cocaine relapse, even after including lifetime alcohol dependence as a covariate in the analyses (X2= 8.95; p = 0.003; hazard ratio, 1.096; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.16) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival probability function in CD individuals for increasing values of BDNF (ng/ml) using the parameter estimates from the Cox proportional hazards regression model (X2= 8.95; p = 0.003; hazard ratio, 1.096; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.16). Each survival function curve represents varying levels of serum BDNF values (predictors). Predictor values reflect the mean (red), −1 (blue), −2 (black) SDs below the mean, and +1 (green), +2 (grey) SDs above the mean. Figure 2 shows an approximate 50% difference in early relapse rates at day 20 for those with BDNF levels +2 SDs above the mean versus those demonstrating mean BDNF levels, and an approximate 90% difference in relapse rates compared with those who demonstrate BDNF levels 2 SDs below the mean.

BDNF levels and frequency of cocaine use

The number of days cocaine was used during the follow-up period was also assessed as an additional measure of relapse risk. Demographic measures of age, IQ, smoking status, gender, history of alcohol dependence, mood, PTSD or anxiety disorders, and clinical variables including years of cocaine use, the amount of cocaine use and the number of days of cocaine use in the 90 days before inpatient treatment, were not associated with frequency of cocaine use during relapse. The standard regression analyses indicated that serum BDNF significantly predicted frequency of cocaine used across the follow-up period and accounted for 22% of the variance, including baseline frequency of cocaine use prior to inpatient treatment as a covariate in the regression model (R2= 0.22, t = 2.16, p = 0.04).

BDNF levels and total amount of cocaine use

Demographic measures of age, IQ, smoking status, gender, history of alcohol dependence, mood, PTSD or anxiety disorders, and clinical variables including years of cocaine use, the days of cocaine use and total amount of cocaine used in the 90 days prior to inpatient treatment, were not associated with the total amount of cocaine used (in grams) during relapse. The standard regression analyses indicated that serum BDNF was a significant predictor of total amount of cocaine used across the 90 days (R2= 0.19, t = 2.05, p = 0.05) and accounted for 19% of the variance in the total amount, including the amount of cocaine used before treatment, as a covariate in the regression model.

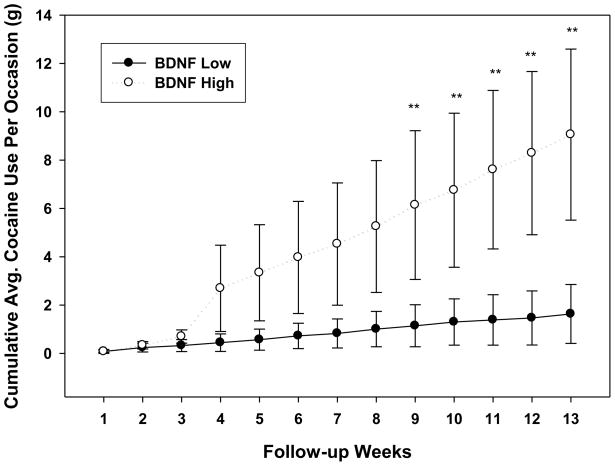

In a secondary analysis, we also assessed whether CD individuals with high serum BDNF versus those with low serum BDNF (median split) used cumulatively more cocaine (average amount) over time during the 90-day period. Using a random mixed effects analysis with Group and Time (weeks 1 to 12) as the fixed effects, subjects as the random effect, we found that CD individuals with high serum BDNF levels used cumulatively more cocaine, on an average, over time than the low BDNF group (Group X Week interaction effect: F12, 345 = 3.06; p < 0.004) and that the high and low serum BDNF groups were different in cumulative cocaine amounts used after week 8 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Differences in the high and low serum BDNF CD groups in the cumulative average amounts of cocaine in grams (with standard errors) used each week of the 90-day follow-up period (Group X Week interaction effect: F12, 345 = 3.06; p < 0.004). Weeks 9, 10, 11 and 12 are significantly different between high and low groups (*p’s <0.05).

Discussion

The findings from this study indicate that abstinent, early recovering CD individuals had significantly higher serum BDNF levels than demographically matched controls. Furthermore, higher BDNF levels were predictive of shorter time to cocaine relapse as well as a higher amount and frequency of cocaine used during the 90 days following treatment discharge. The differences in serum BDNF levels between CD patients and HC participants, and the effects of BDNF on cocaine relapse existed after accounting for any significant demographic, clinical and other drug use variables. These data suggest that peripheral BDNF could represent a potential biomarker of relapse risk in recovering CD individuals.

Our findings are consistent with preclinical research indicating that protracted withdrawal from cocaine dependence could lead to elevations in BDNF levels, which may reflect a compensatory mechanism in response to maladaptive cocaine-related changes in reward system homeostasis (8, 9). In support of this, animal studies indicate that both the patterns of cocaine self-administration as well as drug withdrawal up-regulates BDNF levels within the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, in a time-dependent manner. For example, chronic drug self-administration followed by a week of forced abstinence results in persistent increases in BDNF in the medial prefrontal cortex (9). Similarly, cocaine self-administration followed by withdrawal augments BDNF levels in the NAc and striatum (8). The time-dependent increases in cue-induced cocaine seeking is paralleled by the temporal increases in BDNF protein in the VTA, NAc and amygdala after prolonged (30 days and 90 days), but not short (1 day) period of withdrawal from cocaine self-administration (12).

From a mechanistic perspective, there may be several explanations as to why elevated serum BDNF is predictive of subsequent relapse outcomes in recovering cocaine abusers. First, allostatic changes in stress responses in cocaine patients may modulate BDNF levels. For example, accumulating evidence from our laboratory on 3-week abstinent individuals has characterized cocaine dependence as a chronic stress state with increased HPA axis tone (basal cortisol and ACTH), which is also associated with persistent and elevated anxiety and craving following exposure to stress and drug cues (24–26). Most importantly, these stress system adaptations are clinically relevant as they predict cocaine relapse outcomes in abstinent, cocaine-dependent individuals (27). Because the increases in basal BDNF expression associated with chronic stress in rats sustain the corresponding HPA axis perturbations (28), changes in BDNF levels may reflect tonic and phasic stress-system adaptations associated with cocaine relapse. In support of this, animal research shows that exposure to foot-shock stress enhances corticosterone responses and BDNF expression in brain reward regions in cocaine-experienced mice following a prolonged, but not short, period of cocaine withdrawal (5).

Second, increases in BDNF may have a more direct influence on relapse-related behaviors. In animal studies, local BDNF injections into reward-related brain nuclei (VTA) can potentiate cocaine-seeking following prolonged cocaine abstinence (6) and BDNF infusions into the NAc during self-administration can facilitate stress-induced reinstatement (8). Moreover, BDNF originating from the accumbens neurons is necessary for maintaining drug self-administration (8). Interestingly, the functional consequence of elevated central BDNF on cocaine-seeking appears to be brain region-specific. For example, in contrast to the augmented BDNF-dependent drug-seeking behaviors seen in ventral midbrain-accumbens pathway, the cocaine-induced BDNF increases in the medial prefrontal cortex possibly acts in a compensatory manner to suppress cocaine-seeking and decrease the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine (7, 9). Our results demonstrating that higher peripheral BDNF levels are predictive of shorter time to relapse, higher amount and frequency of cocaine use, are more consistent with the observation of central BDNF potentiating cocaine-seeking behaviors in the ventral midbrain- accumbens pathway.

While the relationship between central and peripheral BDNF is not fully elucidated, recent studies have demonstrated that rat serum and whole blood levels are significantly correlated with brain tissue levels (13, 14). Sartorius et al. (13) found a positive correlation between rat serum and brain BDNF levels (r= 0.4) and Klein et al. (14) demonstrated significant positive correlations between whole blood BDNF levels and hippocampal BDNF in rats (r = 0.44) and between plasma BDNF and hippocampal BDNF in pigs (r = 0.41). Additional support comes from preclinical evidence indicating that peripheral administration of BDNF produces robust cellular and behavioral responses in the brain (15). In addition to its role in the nervous system, peripheral BDNF functions as an immunotrophin, ephitheliotrophin and metabotrophin (29). It is expressed in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, endocrine cells and immune cell subtypes (30). It may be possible, therefore, that elevated levels of peripheral BDNF are representative of central and peripheral neuroadaptations associated with chronic cocaine abuse.

Although we did not measure BDNF levels at admission, there is some evidence suggesting that serum BDNF may be unchanged in CD patients compared with healthy subjects, during residual withdrawal (31). In addition, we did not observe any significant associations between BDNF levels and any pre-admission measures of cocaine use. Thus, it is possible, as suggested from the preclinical research cited above, that increased BDNF levels could reflect protracted withdrawal-related compensatory mechanisms. Although nicotine dependence influences BDNF levels and serum levels are reported to be lower in smokers compared to non-smokers (32), group differences in serum BDNF remained significant even when smoking status was included in the LME model. Serum BDNF levels are also reported to be altered in alcohol-dependent individuals (33), however our group differences in BDNF levels between relapsing and non-relapsing CD patients remained significant even after accounting for lifetime alcohol dependence in group difference analysis and time to relapse analysis.

To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first clinical report examining the association of serum BDNF with subsequent cocaine relapse outcomes. Increases in BDNF predicted a shorter time to initial cocaine relapse in CD individuals and were also significantly associated with escalation of cocaine use after discharge from inpatient treatment. The association of BDNF with relapse outcomes remained significant even after assessing for the contribution of cocaine use prior to inpatient admission, lifetime alcohol dependence, mood disorders, anxiety disorders and PTSD on relapse measures. Specifically, as shown in Figure 2, estimated survival functions of CD patients with serum BDNF above the mean showed a precipitous decrease in survival with only less than 3% surviving relapse by day 30 while those below the mean with lower serum BDNF levels, showed survival at above 80% levels. Preclinical evidence also indicates a critical role for the involvement of BDNF in cocaine reinforcement (34). This notion is supported by the current data demonstrating that elevations in BDNF were associated with greater amounts of cocaine consumed during relapse. It may be that increasing BDNF levels during a stress-related lapse serve to “prime” higher bouts of cocaine consumption by virtue of reaching critical reward thresholds more quickly. Alternatively, it is possible that the BDNF elevations diminish the rewarding effects of the initial cocaine bout such that more cocaine is needed to achieve satiety.

While our sample size is relatively small and future research is warranted to fully assess factors contributing to the association of serum BDNF with relapse outcomes, current results support the need to further explore whether serum BDNF could represent a biomarker of chronic cocaine-related changes. A limitation of our study is that although CD individuals typically demonstrate an upregulated tonic stress system (24), the effects of stressful stimuli on drug-seeking versus other environmental triggers of relapse were not assessed in the current study. BDNF in the cocaine patients was measured after three weeks in a locked inpatient treatment facility and it is possible that residing in a controlled environment for a longer period could have affected their serum BDNF levels. Even though the time-line, follow-back SUC calendar used in our study has been well-documented as a reliable instrument for assessing self-reported, substance abuse outcome measures (27, 35) and urine and SUC data were matched for corroboration, we acknowledge the limitation on relying on delayed retrospective assessments for determining the exact day of relapse (36).

Despite these limitations, this study documents high levels of serum BDNF in CD patients during early recovery from cocaine abuse. In a prospective design, findings indicate that high serum BDNF is predictive of shorter time to cocaine relapse, greater frequency and higher amounts of cocaine used during the follow-up period. While these data are novel, they need replication in a larger sample size of CD individuals, with serum BDNF assessments at multiple time periods during abstinence to fully evaluate whether BDNF changes with cocaine abstinence and to assess the time period during which BDNF levels may be most sensitive to relapse risk.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research Common Fund, and the National Institute for Drug Abuse (NIDA): UL1-DE019586 (Sinha), PL1-DA024859 (Sinha), UL1-RR024139 and the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. We also thank the staff at the Clinical Neuroscience Research Unit for their assistance in completing this study.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Sinha is on the Scientific Advisory Board for Embera Neurotherapeutics and is also a consultant for Glaxo-Smith Klein Pharmaceuticals. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleck JN, Ecke LE, Blendy JA. Endocrine and gene expression changes following forced swim stress exposure during cocaine abstinence in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:15–28. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu L, Dempsey J, Liu SY, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. A single infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the ventral tegmental area induces long-lasting potentiation of cocaine seeking after withdrawal. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1604–1611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5124-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berglind WJ, See RE, Fuchs RA, Ghee SM, Whitfield TW, Jr, Miller SW, et al. A BDNF infusion into the medial prefrontal cortex suppresses cocaine seeking in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DL, Edwards S, Bachtell RK, DiLeone RJ, Rios M, Self DW. Dynamic BDNF activity in nucleus accumbens with cocaine use increases self-administration and relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1029–1037. doi: 10.1038/nn1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadri-Vakili G, Kumaresan V, Schmidt HD, Famous KR, Chawla P, Vassoler FM, et al. Cocaine-induced chromatin remodeling increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription in the rat medial prefrontal cortex, which alters the reinforcing efficacy of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11735–11744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2328-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT, et al. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoenbaum G, Stalnaker TA, Shaham Y. A role for BDNF in cocaine reward and relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:935–936. doi: 10.1038/nn0807-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimm JW, Lu L, Hayashi T, Hope BT, Su TP, Shaham Y. Time-dependent increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system after withdrawal from cocaine: implications for incubation of cocaine craving. J Neurosci. 2003;23:742–747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00742.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartorius A, Hellweg R, Litzke J, Vogt M, Dormann C, Vollmayr B, et al. Correlations and discrepancies between serum and brain tissue levels of neurotrophins after electroconvulsive treatment in rats. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:270–276. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein AB, Williamson R, Santini MA, Clemmensen C, Ettrup A, Rios M, et al. Blood BDNF concentrations reflect brain-tissue BDNF levels across species. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;14:347–353. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt HD, Duman RS. Peripheral BDNF produces antidepressant-like effects in cellular and behavioral models. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2378–2391. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1995. Patient Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brookoff D, Rotondo MF, Shaw LM, Campbell EA, Fields L. Coacaethylene levels in patients who test positive for cocaine. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:316–320. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shipley WC. A self-administering scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. Journal of Psychology. 1940;13:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begliuomini S, Lenzi E, Ninni F, Casarosa E, Merlini S, Pluchino N, et al. Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor daily variations in men: correlation with cortisol circadian rhythm. J Endocrinol. 2008;197:429–435. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersh D, Mulgrew CL, Van Kirk J, Kranzler HR. The validity of self-reported cocaine use in two groups of cocaine abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:37–42. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox D. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinha R, Talih M, Malison R, Cooney N, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympatho-adreno-medullary responses during stress-induced and drug cue-induced cocaine craving states. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:62–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addict Behav. 2008;33:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox HC, Hong KI, Siedlarz K, Sinha R. Enhanced sensitivity to stress and drug/alcohol craving in abstinent cocaine-dependent individuals compared to social drinkers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:796–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinha R, Garcia M, Paliwal P, Kreek MJ, Rounsaville BJ. Stress-induced cocaine craving and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses are predictive of cocaine relapse outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:324–331. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naert G, Ixart G, Maurice T, Tapia-Arancibia L, Givalois L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis adaptation processes in a depressive-like state induced by chronic restraint stress. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;46:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaldakov GN, Tonchev AB, Aloe L. NGF and BDNF: from nerves to adipose tissue, from neurokines to metabokines. Riv Psichiatr. 2009;44:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linker R, Gold R, Luhder F. Function of neurotrophic factors beyond the nervous system: inflammation and autoimmune demyelination. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29:43–68. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v29.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angelucci F, Ricci V, Pomponi M, Conte G, Mathe AA, Attilio Tonali P, et al. Chronic heroin and cocaine abuse is associated with decreased serum concentrations of the nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:820–825. doi: 10.1177/0269881107078491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umene-Nakano W, Yoshimura R, Yoshii C, Hoshuyama T, Hayashi K, Hori H, et al. Varenicline does not increase serum BDNF levels in patients with nicotine dependence. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:276–279. doi: 10.1002/hup.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang MC, Chen CH, Liu SC, Ho CJ, Shen WW, Leu SJ. Alterations of serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in early alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:241–245. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGinty JF, Whitfield TW, Jr, Berglind WJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cocaine addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox HC, Jackson ED, Sinha R. Elevated cortisol and learning and memory deficits in cocaine dependent individuals: relationship to relapse outcomes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1198–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone AA, Shiffman S. Capturing momentary, self-report data: a proposal for reporting guidelines. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:236–243. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]