Abstract

Granzyme B (GZMB) is a proapoptotic serine protease that is released by cytotoxic lymphocytes. However, GZMB can also be produced by other cell types and is capable of cleaving extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. GZMB contributes to abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) through an extracellular, perforin-independent mechanism involving ECM cleavage. The murine serine protease inhibitor, Serpina3n (SA3N), is an extracellular inhibitor of GZMB. In the present study, administration of SA3N was assessed using a mouse Angiotensin II-induced AAA model. Mice were injected with SA3N (0–120 μg/kg) before pump implantation. A significant dose-dependent reduction in the frequency of aortic rupture and death was observed in mice that received SA3N treatment compared with controls. Reduced degradation of the proteoglycan decorin was observed while collagen density was increased in the aortas of mice receiving SA3N treatment compared with controls. In vitro studies confirmed that decorin, which regulates collagen spacing and fibrillogenesis, is cleaved by GZMB and that its cleavage can be prevented by SA3N. In conclusion, SA3N inhibits GZMB-mediated decorin degradation leading to enhanced collagen remodelling and reinforcement of the adventitia, thereby reducing the overall rate of rupture and death in a mouse model of AAA.

Keywords: Granzyme B, aneurysm, aortic dissection, extracellular matrix, serpin, decorin

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) are permanent, focal dilations of the abdominal aorta and occur in up to 9% of the population over 65 years.1 AAA are characterized by structural deterioration of the aortic wall, loss of elastin, extensive tissue remodelling, neovascularization and inflammatory cell infiltration.2, 3 The only treatment options for AAA are open surgical or endovascular repair when the risk of rupture outweighs the risk of surgery. Given the aging population, incidence and recent introduction of early screening programs due to the asymptomatic nature of this disease, much research is being devoted toward the pursuit of noninvasive pharmacological approaches to treat small aneurysms.4

Granzyme B (GZMB) is a 32 kDa serine protease that is released by cytotoxic lymphocytes.5 Upon its internalization, that is facilitated by the pore-forming molecule, perforin, GZMB proteolyses-specific intracellular substrates resulting in apoptotic cell death. However, recently a perforin-independent, extracellular role for GZMB has been proposed.6, 7 In support of the latter, we have shown, using apolipoprotein E (ApoE) × GZMB-double knockout (GDKO) and ApoE × perforin-double knockout (PDKO) mice, that GZMB contributes to AAA through an extracellular, perforin-independent mechanism.7 GZMB is abundantly expressed in the adventitia and thrombus of human AAA specimens; colocalizing to T lymphocytes, mast cells and macrophages in human aortic aneurysms,7 thus corroborating the evidence from the murine model and making GZMB an attractive therapeutic target for the treatment of AAA.

Decorin is a small chondroitin/dermatan sulfate proteoglycan belonging to the family of small leucine-rich proteoglycans. In healthy aorta, decorin localizes primarily to the adventitia, where it interacts extensively with other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and has an important role in ECM assembly. Decorin is important for collagen organization and formation of tight collagen bundles and tensile strength. Furthermore, decorin-deficient mice exhibit skin fragility because of reduced collagen tensile strength.8 In previous work, we identified decorin as a substrate of GZMB and demonstrated that GZMB deficiency prevents the loss of decorin degradation and collagen disorganization in the skin of aging mice.6 With respect to aneurysm pathology, deficient decorin expression is associated with lethal forms of Marfan's syndrome9 and a three-fold downregulation of decorin expression is observed in patients with acute aortic dissection.10

Murine serpina3n (SA3N) is a serine protease inhibitor that is highly expressed in the brain, testes, spleen, lung and thymus and has a high degree of homology with the human α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT). Although in humans there is a single-gene coding for ACT, in mice, repeated duplication has resulted in a cluster of 13 closely related genes at the same locus.11 Of these, SA3N was found to be a potent extracellular inhibitor of GZMB.12 Based on our previous results showing an extracellular role for GZMB in aneurysm pathology,7 the purpose of the present study was to determine whether SA3N could attenuate AAA in mice.

In the current study, SA3N treatment reduced rupture in Angiotensin II (AII)-treated ApoE-KO mice. As decorin functions to regulate matrix assembly by modulating collagen spacing and organization,13 GZMB likely contributes to the loss of adventitial collagen architecture through the cleavage of decorin.

Results

SA3N inhibits murine GZMB activity in vitro

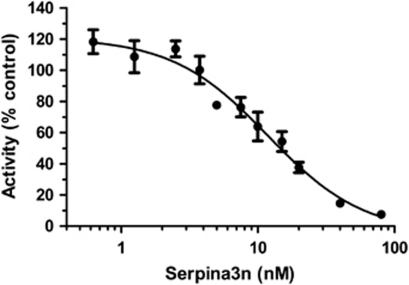

Preincubation with SA3N dose-dependently inhibited cleavage of the GZMB tetrapeptide substrate IEPD-pNA by murine GZMB (Figure 1, IC50=11.83 nM, range 7.925–17.66 nM). These results are consistent with previous results demonstrating that SA3N inhibits both recombinant human GZMB and mouse cytotoxic T lymphocyte degranulate GZMB.12

Figure 1.

SA3N inhibits mGZMB enzymatic activity. Mouse GZMB (20 nM)-mediated cleavage of the colorimetric substrate Ac-IEPD-pNA (1 mM) was inhibited by increasing concentrations of SA3N. Percent activity was determined as the change in initial rate relative to the initial rate in the absence of SA3N. IC50=11.83 nM (range 7.925–17.66 nM). Data represent the mean±S.E.M of three experiments

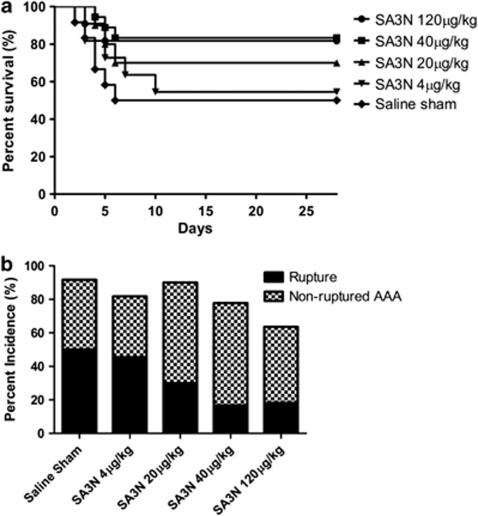

SA3N treatment increases 28-day survival and reduces rate of aneurysm rupture

Necropsy was performed on all mice that died prematurely before the 28-day time point and in all cases confirmed the presence of large ruptured aortic dissections and extensive blood clots in the abdominal cavity suggesting that death was caused by exsanguination following AAA rupture. The survival rate of mice that received a saline sham treatment was 50.0%, whereas serpin treatment improved survival of mice in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2a, SA3N 120 μg/kg, n=9/11, 81.8% SA3N 40 μg/kg, n=15/18, 83.3% SA3N 20 μg/kg, n=7/10, 70.0% SA3N 4 μg/kg, n=6/11, 54.5% saline sham, n=6/12, 50.0%). Log-rank test for trend shows a significant increase in survival with dose of SA3N received (P=0.0207). Mice that received 40 μg/kg SA3N demonstrated a significant increase in survival when compared with mice that received sham treatment (Log-rank/Mantel-Cox test, P=0.0370). Incidence of aneurysm rupture was reduced from 50.0% in saline controls to 18.2% in mice that received 120 μg/kg SA3N; 16.7% in those that received 40 μg/kg (16.7%); 30.0% in those that received 20 μg/kg; and 45.5% in the group that received 4 μg/kg (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

GZMB inhibition increases 28-day survival and reduces rate of aneurysm rupture. (a) Survival. SA3N 120 μg/kg (81.8%, n=11); SA3N 40 μg/kg (83.3%, n=18); SA3N 20 μg/kg (70.0%, n=10); SA3N 4 μg/kg (54.5%, n=11); and saline sham (50.0%, n=12). Log-rank test for trend shows a significant increase in survival with dose of SA3N received (P=0.0207). (b) Total aneurysm incidence and rupture. SA3N 120 μg/kg (incidence 63.3% rupture 18.2%); SA3N 40 μg/kg (77.8% 16.7%); SA3N 20 μg/kg (90.0% 30.0%); SA3N 4 μg/kg (81.8% 45.5%); saline sham (91.7% 50.0%)

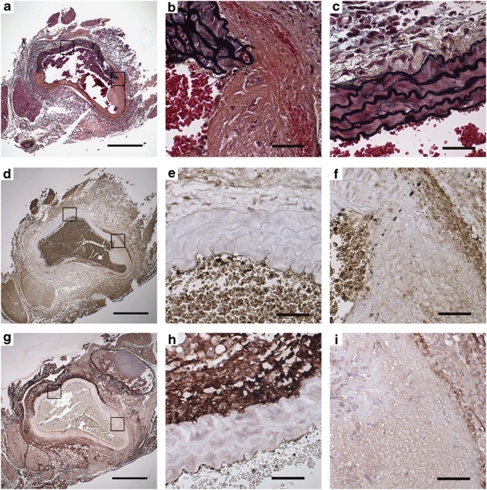

GZMB immunopositivity corresponds to areas of medial disruption and reduced decorin

Serial sections of abdominal aorta from a sham-treated mouse following aortic rupture were stained for Movat's Pentachrome (Figures 3a–c), GZMB (Figures 3d–f) and decorin (Figures 3g–i). Medial GZMB staining (Figure 3f) corresponded to the region of vessel dilation where profound loss of elastic lamellae was observed (Figure 3c). The same region exhibits a marked reduction in decorin (Figure 3i) proximal to the site of aneurysm. Minimal GZMB staining was noted on the non-dilated, healthy side of the vessel wall (Figure 3e), which displayed intact elastic lamellae (Figure 3b) and where robust decorin (Figure 3h) was observed.

Figure 3.

GZMB is abundant in vessels exhibiting medial disruption. Serial sections of abdominal aorta were taken from a sham-treated mouse following aortic rupture and stained for Movat's Pen/tachrome (4 × : a, 40 × : b and c), GZMB (4 × : d, 40 × : e and f) and decorin (4 × : g, 40 × : h and i). GZMB staining by immunohistochemistry (d and f) corresponds to regions of medial disruption and elastin fragmentation (a and c) and loss of decorin in the adventitia (i). The non-dilated side of the aorta has reduced GZMB staining in the media and adventitia (d and e) and corresponds to intact elastic lamellae (a and b) and decorin (g and h), scale bars: 4 × , 500 μm; 40 × , 50 μm

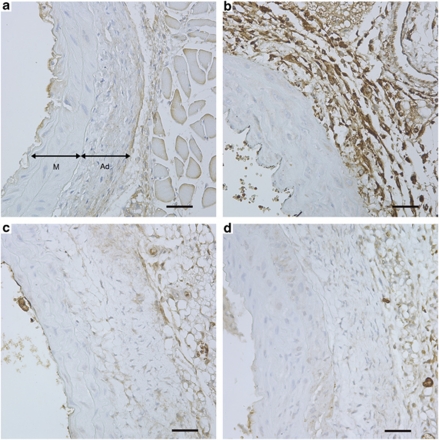

SA3N treatment reduces GZMB immunopositivity

GZMB was detected in the aortas of ApoE-KO sham-treated mice (Figures 3 and 4) that developed AAA and particularly elevated in aneurysms that progressed to rupture. Conversely, immunodetection of GZMB was reduced in animals receiving SA3N treatment, particularly, in the adventitia even when small aneurysms were present (Figure 4). Non-ruptured (NR) aneurysms with similar pathology from both SA3N- and sham-treated groups were assessed for immune cell infiltration (CD3-positive T lymphocytes and activated macrophages); however, no significant difference in the levels of T lymphocytes or macrophages was observed (data not shown).

Figure 4.

GZMB immunopositivity is reduced in SA3N-treated mice. GZMB staining is minimal in healthy aorta (a) in both the media (represented by ‘M') and the adventitia (represented by ‘Ad'). GZMB expression is increased particularly in the adventitia of sham-treated mice that experienced rupture (b). Reduced GZMB was observed in SA3N-treated mice with no AAA (c) and small, remodelled AAA (d), scale bars: 4 × , 500 μm; 40 × , 50 μm

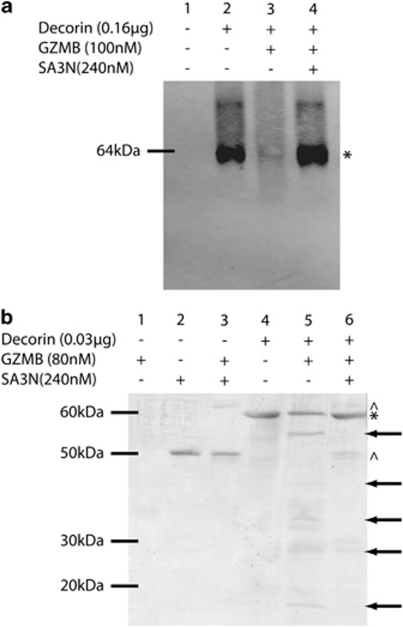

SA3N inhibits GZMB-mediated decorin cleavage in vitro

Active, purified human GZMB was incubated in vitro with recombinant human decorin protein. Decorin loss was observed by western blot (Figure 5a) and cleavage products were detected by Ponceau staining (Figure 5b). GZMB incubation resulted in production of numerous cleavage fragments ranging in size from approximately 15–55 kDa. GZMB-mediated decorin cleavage was abolished in the presence of SA3N.

Figure 5.

GZMB cleavage of decorin is prevented by pre-incubation with SA3N in vitro. Purified GZMB was pre-incubated with or without SA3N for 25 min at RT before incubation with recombinant human decorin for 24 h at RT. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and visualized by western blotting for decorin (a) and Ponceau stain (b). In a, full-length decorin is indicated by an asterisk (*) and is visible at ∼65 kDa in lane 1. Decorin is severely reduced following incubation with GZMB in lane 2. In lane 3, decorin loss is not observed following pre-incubation of GZMB with SA3N. In b, SA3N and SA3N–GZMB complex at approximately 47 and 70 kDa, respectively (indicated by ^) are visible in lanes 2, 3 and 6. Full-length decorin is indicated by the asterisk (*) at approximately 65 kDa in lanes 4, 5 and 6. Decorin cleavage fragments in lane 5 are marked by arrows on the right side of the membrane

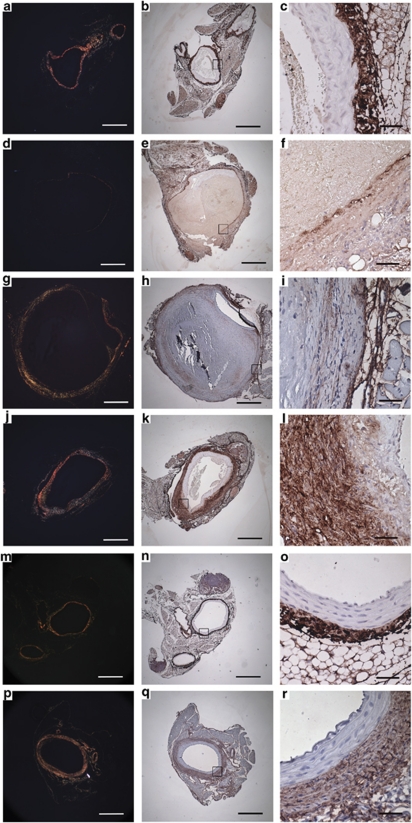

SA3N treatment corresponds to increased decorin and adventitial collagen remodelling

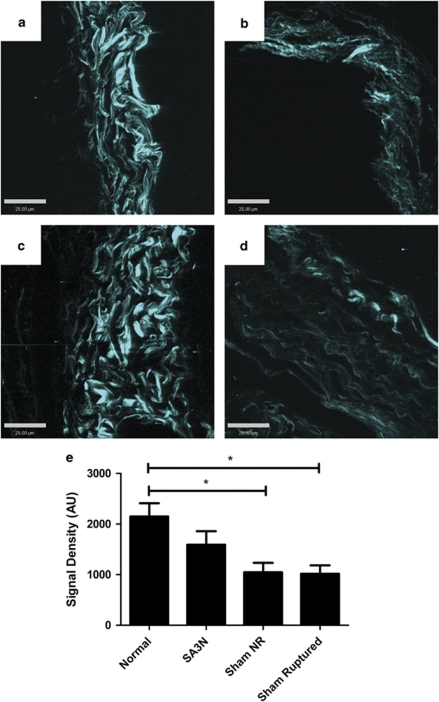

Decorin was markedly reduced in the adventitial regions of aortas from sham-treated mice that developed aneurysm (Figure 6i) and exhibited rupture (Figure 6f) compared with aortas of healthy animals (Figure 6c). The adventitia surrounding the thrombus was thin and collagen content was also greatly reduced (Figures 6d and g). With picrosirius red staining under polarized light, adventitial collagen fibers from sham-treated ruptured and NR aneurismal aorta (Figures 6d and g) appear green and yellow, whereas adventitial collagen fibers from healthy aorta (Figure 6a) have a higher proportion of orange and red fibers, indicating higher fiber density. In comparison, the majority of aneurysms observed in the GDKO and SA3N-treated groups that received the two highest doses (120 and 40 μg/kg) were small aneurysms with minimal thrombus that did not progress to rupture and displayed thickened adventitia, increased decorin staining (Figures 6l and r) and collagen fibers of higher density (Figures 6j and p) compared with ruptured, sham-treated aortas. Imaging by second harmonic generation (SHG) confirmed a reduction in collagen density loss in SA3N-treated mice compared with the sham-treated groups (Figure 7). Analysis by one-way analysis of variance demonstrated a significant difference across all groups (P=0.0226). SHG signal density representing fiber density was reduced in ruptured and NR sham-treated groups compared with normal and SA3N-treated mice, however, only the difference between normal and sham-treated groups achieved statistical significance (sham NR, P=0.0268; sham ruptured, P=0.0218). Notable differences in collagen architecture and overall appearance were also observed in sham-treated aneurismal aortas compared with healthy and SA3N-treated groups, with profound loss of collagen organization and thick bundle formation.

Figure 6.

SA3N and GZMB deficiency promotes adventitial thickening and increased decorin content in AAA. Sections stained with picrosirius red are shown in the first column (a, d, g, j, m and p). Tissues immunostained for decorin are shown in the second column (b, e, h, k, n and q) and enlarged for emphasis at 40 × in the third column (c, f, i, l, o and r). When stained with picrosirius red, thick collagen fibers evidenced by strong birefringence (red) under polarized light (a) are visible in the adventitia of healthy normal aorta, as well as robust decorin staining (b and c). Non-ruptured aneurysms from sham-treated mice exhibit bulbous thrombus, reduced decorin staining (h and i) and thinner collagen fibers of lower density (g) as evidenced by predominance of yellow color when stained with picrosirius red and seen under polarized light. Ruptured aneurysms from sham-treated mice demonstrate even greater loss of collagen content (d) and a similarly reduced amount of decorin in the adventitia (e and f) compared with healthy aortas. In comparison, aortas from mice that received SA3N (120 μg/kg) before AII pump implantation demonstrate a significant increase in collagen and a thickened adventitial layer, with a greater proportion of red and orange fibers under polarized light (j). Decorin content in the adventitia is also greatly increased (k and l). Morphology and levels of collagen and decorin in normal, non-diseased aorta from GDKO mice resemble healthy controls (m, n and o) while GDKO that develop small, localized aneurysm display thickened adventitia (p) and increased decorin content (q and r) similar to SA3N-treated mice. Scale bars: 4 × , 500 μm; 40 × , 50 μm

Figure 7.

SA3N treatment reduces the loss of collagen fiber density in AII-treated ApoE-KO mice. Adventitial collagen from healthy mouse (a), sham-treated mouse with ruptured aorta (b), SA3N-treated mouse (c) and sham-treated mouse, non-ruptured (NR) aorta (d) were assessed by SHG. Scale bar: 25 μm. SHG signal densities are summarized in e (n=3 per group, *P<0.05)

Discussion

Although once thought to function exclusively as a proapoptotic, immune-secreted serine protease, GZMB can exert other perforin- and/or apoptosis-independent roles in pathogenesis.14 Indeed, it is now well established that GZMB accumulates extracellularly in bodily fluids, such as plasma, synovial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage, during conditions of aging and chronic inflammation (reviewed in Hendel et al.15). Furthermore, in addition to cytotoxic lymphocytes, other cell types, both immune and non-immune, are capable of expressing and secreting this protease alone, or in combination with perforin, into the extracellular milieu (reviewed in Hendel et al.15). GZMB also retains its activity in plasma16 and is capable of cleaving ECM in vitro (reviewed in Hendel et al.15). As no extracellular inhibitors of GZMB have been identified in humans, in addition to being a marker of inflammation, extracellular GZMB activity may contribute to vascular pathogenesis. Indeed, in human atherosclerosis, elevated levels of GZMB are associated with increased disease severity and unstable plaque formation.17 In further support of an extracellular role for GZMB in vascular disease, and of relevance to the present manuscript, GZMB contributes to AII-induced aortic aneurysm in a perforin-independent manner.7 In the latter study, although GDKO mice were afforded significant protection against both progression and rupture compared with ApoE-KO controls, no protection was observed in PDKO mice. As this study suggested that extracellular GZMB was responsible for AAA in part through the cleavage of ECM, the purpose of the present study was to determine whether a known murine extracellular inhibitor of GZMB could elicit a similar effect.

In the present study, SA3N significantly improved survival by reducing adventitial decorin degradation and preventing aneurysm rupture. SA3N treatment also resulted in a decrease in overall incidence of aneurysm development that did not reach significance; however, the small unruptured aneurysms in the 120 μg/kg- and 40 μg/kg-treated groups were morphologically different to those observed in sham-treated animals. Aneurysms in the sham-treated group consistently exhibited medial hematomas consistent to that previously observed by us and others7, 18, 19 with a disordered, fibrous adventitia displaying mostly yellow–green fibers when stained with picrosirius red, indicating less tightly packed collagen fibers of smaller diameter. In contrast, aneurysms in the GDKO and SA3N-treated groups, especially at the higher doses, demonstrated a remarkable thickening of the adventitial layer with red and orange collagen fibers when stained with picrosirius red. This suggests that the collagen fibers in the adventitia of these mice exhibited increased thickness, density and alignment20 compared with their sham-treated counterparts. Indeed, when examined by SHG, collagen from sham-treated groups demonstrated a significant reduction in collagen fiber density and exhibited unidirectional realignment of fibers, whereas collagen morphology from SA3N-treated aortas more closely resembled the interwoven network as seen in healthy controls.

The adventitia is responsible for maintaining the circumferential structural integrity of the vessel21 and its tensile strength is largely reliant on the organization and morphology of its major constituent, type I collagen.22 Although medial elastin loss is a critical factor in aneurysm formation, aneurismal growth and rupture is dependent on defective collagen homeostasis.23 Consistent differences in the optical properties of aneurismal collagen have been noted when compared with normal vessels, suggesting a difference in fibril organization.24 Collagen content is both disorganized and reduced in human aneurysms and dissections of the ascending aorta, whereas in human AAA, turnover of collagen III is increased as evidenced by increased levels of aminoterminal propeptide of type III collagen and associated with impaired collagen fibrillogenesis.25, 26 In a study on collagen crosslinking, Carmo et al.27 observed an overall decrease in collagen content in human AAA specimens and concluded that new collagen synthesis in aneurismal tissues was defective and lacking proper crosslinking, rendering it more susceptible to proteolytic attack.

Our findings related to the loss of collagen organization and packing are consistent with the recent findings of Lindeman et al.28 in which a loss of collagen microarchitecture was observed in the adventitia of AAA and Marfan syndrome patients. In the latter, it was proposed that the loose, ribbon-like appearance of collagen that is observed in a normal adventitia, but not aneurysmal adventitia, acts as a coherent network to maintain mechanical strength and allows for vessel dilation and that this is lost in growing aneurysms.28 Given that we had also observed a loss of adventitial collagen organization in the mouse AAA model, we were interested in how GZMB might affect this process.

In saline-treated mice with rupture, strong intracellular and extracellular GZMB staining was apparent in the adventitia (Figure 4). In contrast, minimal staining was evident in the serpin-treated groups. Although these results suggest that serpin administration could lower GZMB levels, it is also very possible that the non-competitive binding and conformational change of GZMB within the GZMB–serpin complex results in reduced recognition and binding of the antibody to GZMB. Alternatively, it is possible that the non-functional GZMB–serpin complex may have been cleared from the vessel. In Figure 3, normal levels of adventitial decorin staining were observed on the non-dilated side of the vessel where the elastic lamellae are still intact. Conversely, on the dilated side where aortic rupture occurred and GZMB staining was most prominent, decorin staining was nearly absent. We have previously shown that GZMB degrades decorin in vitro6 and here we demonstrate that preincubation with SA3N is capable of preventing cleavage by GZMB (Figure 5). Decorin staining was markedly elevated in GDKO, further implying that GZMB is responsible for decorin degradation. Decorin immunopositivity was strong in SA3N-treated mice (Figure 6), which also displayed reduced levels of GZMB immunopositivity (Figure 4) in the thickened adventitia compared with sham controls. GZMB staining was elevated in these sham controls, particularly when rupture was observed (Figure 4), whereas decorin staining was nearly depleted in the adventitia surrounding the medial thrombus (Figure 6) and at zones of dilation.

Because collagen is the main structural element of the adventitia, providing the mechanical and tensile strength, as well as forming the scaffold for the ECM, the organization and orientation of the collagen fibrils is critical and largely determined by interactions with proteoglycans such as decorin through interfibrillar bridges.29 Decoron, the core protein of the decorin molecule, functions as a strong anchor for the elastic glycan bridge between each decorin molecule and collagen fibril, conveying elasticity and allowing for reversible deformation during movement of the vessel wall.30 Decorin is a key mediator of collagen fibrillogenesis13, 31 and its incorporation into collagen fibrils improves tensile properties.32 Decorin-deficient mice have fragile skin with markedly reduced tensile strength.8, 13 Dermal collagen from these mice exhibit highly irregular fibril diameter and abnormal fibrillar organization,13 suggesting that decorin has a crucial role in fibril formation, fusion and maintaining stability. Furthermore, Iwasaki et al.33 have found that in vitro collagen gels cultured in the absence of, or with low concentrations of decorin produced highly porous fiber networks with poor elasticity, whereas gels cultured with higher concentrations of decorin produced fiber networks of significantly higher density and elastic properties. This corroborates our own observation of higher adventitial collagen fiber density in SA3N-treated animals that also present with correspondingly higher decorin immunopositivity compared with sham-treated controls. As further support, we have recently shown that decorin cleavage and loss of collagen fiber density are prevented in the skin of GZMB-deficient mice using a murine model of accelerated aging.6

Along with other proteoglycans, decorin can sequester and regulate the activity of growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-β,34 fibroblast growth factor-2,35 tumor necrosis factor-α36 and platelet-derived growth factor,37 making decorin a critical regulator of numerous receptor-specific signalling cascades and giving decorin the ability to influence repair and remodelling processes in damaged tissues. Under specific conditions, decorin binds to the forming collagen fibrils, functioning as a spacer and slowing down collagen fibril association and fusion. This allows sufficient time for optimal interactions and crosslinking to occur, and thus forces the formation of well-organized fibrils of uniform diameter optimized for local conditions.13 In the present study, SA3N treatment reduced decorin cleavage and aneurismal rupture. Similar observations of adventitial thickening and reduced loss of decorin were observed in GZMB-deficient mice suggesting that the cleavage of decorin is most likely due to GZMB. As further support, SA3N treatment prevented GZMB cleavage of decorin in vitro. Based on these findings, we propose that reducing GZMB in the inflammatory milieu surrounding aneurismal induction facilitates adventitial collagen remodelling by preventing the degradation of decorin, thereby facilitating decorin-mediated fibrillogenesis and reinforcement of the adventitia. The vessel thus retains sufficient tensile strength and flexibility to maintain structural integrity, constrain dilation and prevent rupture.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that SA3N improves survival and reduces the incidence of aneurysm rupture in a murine model of AAA by preventing decorin degradation and subsequent collagen disorganization in the adventitia of the abdominal aorta. We have previously shown that GZMB is abundantly expressed in human AAA and was colocalized to numerous immune cell types that are known to have roles in the pathogenesis of thoracic aortic aneurysm and AAA.7 Although we did not detect a change in CD3+ lymphocytes or macrophages following SA3N treatment compared with NR sham-treated controls at 28 days post induction, immune cell infiltration is difficult to accurately assess in ruptured aortas in this model and will require additional study at earlier time points. We have also previously determined that GZMB deficiency, but not perforin deficiency protects against AAA development in this model.7 Although this rules out a role for GZMB/perforin-mediated apoptosis, there is indeed the possibility that GZMB could be contributing to aneurysm development through GZMB-mediated anoikis through ECM cleavage. Indeed, we and others have shown that GZMB cleavage of fibronectin can result in detachment-induced death of fibroblasts,38 endothelial cells39 and smooth muscle cells;40 the loss of which may significantly contribute to aneurysm pathogenesis.

A possible limitation of this current study is that although SA3N is a potent inhibitor of GZMB, SA3N is also known to bind and inhibit human leukocyte elastase (neutrophil elastase),11 another protease implicated in AAA pathogenesis. Leukocyte elastase, however, does not cleave decorin.41 As elastase-digested aortas are utilized to assess decorin and biglycan expression in AAA,41 it is highly unlikely that inhibition of leukocyte elastase was responsible for prevention of decorin degradation in this model. This is further supported by the observation that decorin cleavage is also prevented in GZMB-deficient mice in the present study. While the generation of GZMB inhibitors is in progress, at the present time, no other extracellular inhibitors of mouse GZMB are available. However, given that SA3N is a potent inhibitor of GZMB, in combination with the fact that we have shown that small aneurysms in GDKO and SA3N-treated mice develop similar morphology and show reduced propensity to decorin cleavage, adventitial collagen disorganization and rupture, a strong argument can be made for pursuing further investigations into GZMB as a therapeutic target for reducing the progression and rupture of aortic aneurysms.

Materials and Methods

Murine GZMB enzymatic activity assay

Increasing serpin concentrations (0.625–80 nM) were pre-incubated with active recombinant mGZMB (20 nM, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 25 min in reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 10% sucrose, 0.1% CHAPS, 5 mM DTT). Cleavage of the colorimetric GZMB substrate Ac-IEPD-pNA (1 mM, Calbiochem, EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ, USA) in duplicate reactions was monitored by measuring absorbance at 405 nm using a plate reader (Magellan Tecan SaFire 2, Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland) in kinetic mode. The initial rate of each reaction was calculated, and percent mGZMB activity for each concentration determined relative to mGZMB activity in the absence of inhibitor. Inhibition was determined in three separate experiments.

Mice

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal experimentation approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of the University of British Columbia. ApoE-KO mice and GZMB-KO mice (C57Bl/6 background, Stock numbers 002052 and 002248) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA. ApoE × GDKO mice were generated by crossing ApoE-KO and GZMB-KO mouse strains as described previously.7 Genotyping was performed using primers and PCR protocols designed by Jackson Laboratories. All mice were housed at The Genetic Engineered Models facility at St. Paul's Hospital, University of British Columbia.

AII infusion

Aneurysm was induced by AII infusion as described previously.7 In brief, ApoE-KO and GDKO mice aged 11–13 weeks received AII (Sigma Aldrich) infusion at 1000 ng/min/kg for 28 days via micro-osmotic pumps (ALZET model 1004, DURECT Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA), which were surgically implanted subcutaneously posterior to the scapula.

SA3N treatment

ApoE-KO mice were given a tail vein injection of saline (sham treatment) (n=12) or recombinant SA3N diluted in PBS at one of four doses: 120 μg/kg per mouse (n=11), 40 μg/kg per mouse (n=18), 20 μg/kg per mouse (n=10) or 4 μg/kg per mouse (n=11) before pump implantation.

Tissue collection and preparation

At 28 days following minipump implantation, tissues from surviving mice were harvested and aortas characterized as described previously.7 Briefly, a gross description of the aorta was made at point of harvest and these observations were subsequently confirmed by a clinical and experimental pathologist blinded to treatment type. Necropsies were performed on all mice that died prematurely before the 28-day time point to determine cause of death. Tissues were stored in 10% formalin overnight before embedding and sectioning. Aortic segments were isolated from the abdominal aorta immediately above the renal arteries. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and serial sectioned into 10 μm sections.

Histological analysis

Abdominal aortic sections were stained with Movat's pentachrome and picrosirius red. Immunohistochemistry was performed using rabbit anti-mouse GZMB (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), goat anti-mouse decorin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) as described previously.6

In vitro decorin cleavage assays

Western blot

Purified human GZMB (100 nM; Axxora, San Diego, CA, USA) was preincubated with or without recombinant SA3N (240 nM) in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, for 25 min at RT before incubation with recombinant human decorin (0.16 μg; Abnova, Walnut, CA, USA) for 24 h at RT. After incubation, proteins were denatured, separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 10% skim milk. The membrane was probed using a mouse anti-human decorin antibody (1 : 200, R&D Systems) and IRDye 800 conjugated affinity purified anti-mouse IgG (1 : 3000, Rockland Inc., Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Bands were imaged using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Ponceau stain

Purified human GZMB (80 nM; Axxora) was preincubated with or without recombinant SA3N (240 nM) in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, for 25 min at RT before incubation with recombinant human decorin (0.3 μg; Abnova) for 24 h at RT. After incubation, proteins were denatured, separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Ponceau stain was used to identify cleavage fragments.

Second harmonic generation microscopy and collagen analysis

Collagen structures in histological specimens were visualized using SHG microscopy as described previously.42, 43 Ultra-short laser pulse was focused on the specimen through a Leica 63 × /1.2 NA Plan-Apochromat water immersion objective (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). SHG signal in the forward direction originating from the histological specimens was captured using a non-descanned detector in the transmission geometry. In this non-descanned PMT detector (R6357, Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan), a 440/20 nm band pass filter (MP 440/20, Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT, USA) was used to collect spectrally clean SHG signal. The gain and offset of the PMTs were adjusted for optimized detection using the color gradient to avoid pixel intensity saturation and background and these settings kept constant for all measurements. The 3D image restoration from the collected z-section images was performed using Volocity software (Improvision, Coventry, UK). For collagen signal density calculations, a noise removal filter with kernel size of 3 × 3 was used to define the boundary between foreground and background, and the lower threshold in the histogram was set to mean voxel intensity value. The total SHG signal intensity values thus generated were normalized by the total collagen volume (μm3) and expressed in arbitrary units (AU).

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was compiled in Graphpad Prism 5 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). SA3N IC50 concentrations were determined using nonlinear regression analysis. Survival curves were assessed using Log-rank test for trend and Log-rank/Mantel-Cox analysis. AAA incidence was assessed by χ2-test for trend across all groups. SHG collagen signal density was assessed by one-way analysis of variance and unpaired Student's t-test. For all tests, significant difference was set at P<0.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Drs. Granville and Bleackley) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of British Columbia and Yukon (Dr. Granville). Ms. Ang is a recipient of an MSFHR trainee award and a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship. Ms. Boivin is a recipient of a MSFHR trainee award and an NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarship. Dr. Williams is a recipient of a CIHR Fellowship award and a CIHR-IMPACT Strategic Training Post-Doctoral Fellowship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Glossary

- AAA

abdominal aortic aneurysm

- ACT

α1-antichymotrypsin

- AII

angiotensin II

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GDKO

GZMB-double knockout

- GZMB

granzyme B

- NR

non-ruptured

- PDKO

perforin-double knockout

- SA3N

Serpin A3N

- SHG

second harmonic generation.

Dr. Granville is a member of the scientific advisory board and consultant to viDA Therapeutics. viDA did not provide any inhibitors, funding, reagents or input into the design, implementation or interpretation of the experiments and/or data in this study. Ms. Ang, Ms. Boivin, Dr. Williams, Ms. Zhao, Dr. Abraham, Dr. Carmine-Simmen, Dr. McManus and Dr. Bleackley declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by V De Laurenzi

References

- Thompson RW. Detection and management of small aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205093461910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Upchurch GR., Jr Current concepts in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:584–588. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta J, Laurila A, Paakko P, Haukipuro K, Sormunen R, Parkkila S, et al. Chronic inflammation and elastin degradation in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter BT, Terrin MC, Dalman RL. Medical management of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2008;117:1883–1889. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.735274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin WA, Cooper DM, Hiebert PR, Granville DJ. Intracellular versus extracellular granzyme B in immunity and disease: challenging the dogma. Lab Invest. 2009;89:1195–1220. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert PR, Boivin WA, Abraham T, Pazooki S, Zhao H, Granville DJ. Granzyme B contributes to extracellular matrix remodeling and skin aging in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain CM, Ang LS, Boivin WA, Cooper DM, Williams SJ, Zhao H, et al. Perforin-independent extracellular granzyme B activity contributes to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1038–1049. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV. Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:729–743. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L, Kainulainen K, Krusius T, Makinen P, Schollin J, Gustavsson KH, et al. Deficient expression of the gene coding for decorin in a lethal form of Marfan syndrome. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17780–17785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed SA, Sievers HH, Hanke T, Richardt D, Schmidtke C, Charitos EI, et al. Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes in patients with acute aortic dissection. Biomark Insights. 2009;4:81–90. doi: 10.4137/bmi.s2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AJ, Irving JA, Rossjohn J, Law RH, Bottomley SP, Quinsey NS, et al. The murine orthologue of human antichymotrypsin: a structural paradigm for clade A3 serpins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43168–43178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipione S, Simmen KC, Lord SJ, Motyka B, Ewen C, Shostak I, et al. Identification of a novel human granzyme B inhibitor secreted by cultured sertoli cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5051–5058. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed CC, Iozzo RV. The role of decorin in collagen fibrillogenesis and skin homeostasis. Glycoconj J. 2002;19:249–255. doi: 10.1023/A:1025383913444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granville DJ. Granzymes in disease: bench to bedside. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:565–566. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendel A, Hiebert PR, Boivin WA, Williams SJ, Granville DJ. Granzymes in age-related cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:596–606. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurschus FC, Kleinschmidt M, Fellows E, Dornmair K, Rudolph R, Lilie H, et al. Killing of target cells by redirected granzyme B in the absence of perforin. FEBS Lett. 2004;562:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjelland M, Michelsen AE, Krohg-Sorensen K, Tennoe B, Dahl A, Bakke S, et al. Plasma levels of granzyme B are increased in patients with lipid-rich carotid plaques as determined by echogenicity. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:e142–e146. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraff K, Babamusta F, Cassis LA, Daugherty A. Aortic dissection precedes formation of aneurysms and atherosclerosis in angiotensin II-infused, apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1621–1626. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085631.76095.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan D, Hiss Y, Hirshberg A, Bubis JJ, Wolman M. Are the polarization colors of picrosirius red-stained collagen determined only by the diameter of the fibers. Histochemistry. 1989;93:27–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00266843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson B, Lanne T, Vernersson E, Hansen F. Sex difference in the mechanical properties of the abdominal aorta in human beings. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:959–969. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzapfel GA.Collagen in arterial walls: Biomechanical aspectsIn: Fratzl P (ed)Collagen: Structure and Mechanics Springer: New York; 2008285–324. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RW, Geraghty PJ, Lee JK. Abdominal aortic aneurysms: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Curr Probl Surg. 2002;39:110–230. doi: 10.1067/msg.2002.121421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker P, Schwab ME, Canham PB. The molecular organization of collagen in saccular aneurysms assessed by polarized light microscopy. Connect Tissue Res. 1988;17:43–54. doi: 10.3109/03008208808992793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta J, Juvonen T, Haukipuro K, Juvonen M, Kairaluoma MI. Increased turnover of collagen in abdominal aortic aneurysms, demonstrated by measuring the concentration of the aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen in peripheral and aortal blood samples. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode MK, Soini Y, Melkko J, Satta J, Risteli L, Risteli J. Increased amount of type III pN-collagen in human abdominal aortic aneurysms: evidence for impaired type III collagen fibrillogenesis. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:1201–1207. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.109743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo M, Colombo L, Bruno A, Corsi FR, Roncoroni L, Cuttin MS, et al. Alteration of elastin, collagen and their cross-links in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:543–549. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman JH, Ashcroft BA, Beenakker JW, van Es M, Koekkoek NB, Prins FA, et al. Distinct defects in collagen microarchitecture underlie vessel-wall failure in advanced abdominal aneurysms and aneurysms in Marfan syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:862–865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910312107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE. Supramolecular organization of extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans, in vitro and in the tissues. Faseb J. 1992;6:2639–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel JP, Eid A, Antipova O, Bella J, Scott JE. Decorin core protein (decoron) shape complements collagen fibril surface structure and mediates its binding. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, Robinson PS, Beason DP, Carine ET, et al. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1436–1449. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pins GD, Christiansen DL, Patel R, Silver FH. Self-assembly of collagen fibers. Influence of fibrillar alignment and decorin on mechanical properties. Biophys J. 1997;73:2164–2172. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Hosaka Y, Iwasaki T, Yamamoto K, Nagayasu A, Ueda H, et al. The modulation of collagen fibril assembly and its structure by decorin: an electron microscopic study. Arch Histol Cytol. 2008;71:37–44. doi: 10.1679/aohc.71.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen LM, Heinegard D, Twardzik DR, Border WA, et al. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor beta. Biochem J. 1994;302 (Pt 2:527–534. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penc SF, Pomahac B, Winkler T, Dorschner RA, Eriksson E, Herndon M, et al. Dermatan sulfate released after injury is a potent promoter of fibroblast growth factor-2 function. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28116–28121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufvesson E, Westergren-Thorsson G. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha interacts with biglycan and decorin. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nili N, Cheema AN, Giordano FJ, Barolet AW, Babaei S, Hickey R, et al. Decorin inhibition of PDGF-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell function: potential mechanism for inhibition of intimal hyperplasia after balloon angioplasty. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:869–878. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63447-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J, Wallich R, Ebnet K, Iden S, Zentgraf H, Martin P, et al. Granzyme B is expressed in mouse mast cells in vivo and in vitro and causes delayed cell death independent of perforin. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1768–1779. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzza MS, Zamurs L, Sun J, Bird CH, Smith AI, Trapani JA, et al. Extracellular matrix remodeling by human granzyme B via cleavage of vitronectin, fibronectin, and laminin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23549–23558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy JC, Hung VH, Hunter AL, Cheung PK, Motyka B, Goping IS, et al. Granzyme B induces smooth muscle cell apoptosis in the absence of perforin: involvement of extracellular matrix degradation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2245–2250. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147162.51930.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Decreased biglycan expression and differential decorin localization in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham T, Carthy J, McManus B. Collagen matrix remodeling in 3-dimensional cellular space resolved using second harmonic generation and multiphoton excitation fluorescence. J Struct Biol. 2010;169:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham T, Hogg J. Extracellular matrix remodeling of lung alveolar walls in three dimensional space identified using second harmonic generation and multiphoton excitation fluorescence. J Struct Biol. 2010;171:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]