Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has an extraordinary capacity to evade the activity of antibiotics through a complex interplay of intrinsic and mutation-driven resistance pathways, which are, unfortunately, often additive or synergistic, leading to multidrug (or even pandrug) resistance. However, we show that one of these mechanisms, overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump (driven by inactivation of its negative regulator NfxB), causes major changes in the cell envelope physiology, impairing the backbone of P. aeruginosa intrinsic resistance, including the major constitutive (MexAB-OprM) and inducible (MexXY-OprM) efflux pumps and the inducible AmpC β-lactamase. Moreover, it also impaired the most relevant mutation-driven β-lactam resistance mechanism (constitutive AmpC overexpression), through a dramatic decrease in periplasmic β-lactamase activity, apparently produced by an abnormal permeation of AmpC out of the cell. While these results could delineate future strategies for combating antibiotic resistance in cases of acute nosocomial infections, a major drawback for the potential exploitation of the described antagonistic interaction between resistance mechanisms came from the differential bacterial physiology characteristics of biofilm growth, a hallmark of chronic infections. Although the failure to concentrate AmpC activity in the periplasm dramatically limits the protection of the targets (penicillin-binding proteins [PBPs]) of β-lactams at the individual cell level, the expected outcome for cells growing as biofilm communities, which are surrounded by a thick extracellular matrix, was less obvious. Indeed, our results showed that AmpC produced by nfxB mutants is protective in biofilm growth, suggesting that the permeation of AmpC into the matrix protects biofilm communities against β-lactams.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most frequent and severe (up to 50% mortality) causes of acute nosocomial infections (31). No less concerning, chronic respiratory infection by P. aeruginosa is the main driver of morbidity and mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory diseases (18).

The treatment of these infections is severely compromised by the extraordinary capacity of this pathogen to evade the activity of nearly all available antibiotics through a complex interplay of intrinsic and mutation-driven resistance pathways (4, 16). The biofilm mode of growth, a hallmark of chronic infections, provides P. aeruginosa populations with differentiated structural and physiological properties that further enhance its capacity to escape from the activity of antimicrobial treatments (3, 9). Among the most relevant resistance pathways, in both acute and chronic infections, are those leading to the overexpression of the chromosomal β-lactamase AmpC, which is frequently triggered by the inactivation of the nonessential penicillin-binding protein PBP4 and confers high-level resistance to antipseudomonal penicillins and cephalosporins (20), along with the inactivation of the carbapenem porin OprD or the overexpression of several efflux pumps encoded in its genome (16, 17, 25). Unfortunately, the combinations of these resistance pathways are often additive or synergistic, leading to multidrug (or even pandrug) resistance. However, one of these mechanisms, overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump (caused by inactivation of its negative regulator NfxB), besides conferring resistance to the pump substrates, determines a marked hypersusceptibility to other relevant antipseudomonal agents, including most β-lactams and aminoglycosides (8), perhaps suggesting the occurrence of antagonistic interactions with other resistance mechanisms.

During the initial steps of this research, we learnt that it is in fact the case that overexpression of this efflux pump impairs highly relevant resistance mechanisms; the β-lactam resistance driven by the overexpression of AmpC is particularly worth noting. These results prompted us to follow a global approach to decipher the complexity of the underlying mechanisms, providing relevant information for the identification of new targets for fighting P. aeruginosa intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms, but with a major drawback resulting from the differential bacterial physiology characteristics of biofilm communities, a hallmark of chronic infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and construction of PAO1 knockout mutants.

The complete list of strains and plasmids used or constructed in this work is shown in Table 1. Single- and multiple-knockout nfxB, mexD, dacB (PBP4), oprM, mexR, or ampC mutants were constructed using the Cre-lox system for gene deletion and antibiotic resistance marker recycling following previously described protocols (20, 26). Briefly, upstream and downstream PCR products (Table 2) of each gene were digested with either BamHI or EcoRI and HindIII and cloned by three-way ligation into pEX100Tlink with a deletion with respect to the HindIII site and opened by EcoRI and BamHI. The resulting plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli strain XL1Blue, and transformants were selected on ampicillin-LB agar plates (30 μg/ml). The lox-flanked gentamicin resistance cassette (aac1) obtained by HindIII restriction of plasmid pUCGmlox was cloned into the single site for this enzyme formed by the ligation of the two flanking fragments. The resulting plasmids were again transformed into E. coli strain XL1Blue, and transformants were selected on ampicillin (30 μg/ml)-5 gentamicin (μg/ml)-LB agar plates. Plasmids were then transformed into the E. coli S17-1 helper strain. Knockout mutants were generated by conjugation followed by selection of double recombinants by the use of sucrose (5%)-cefotaxime (1 μg/ml)-gentamicin (30 μg/ml)-LB agar plates. Double recombinants were checked first by screening for susceptibility to carbenicillin (200 μg/ml) and afterwards by PCR amplification and sequencing. For the recycling of the gentamicin resistance cassettes, plasmid pCM157 was electroporated into the different mutants. Transformants were selected in tetracycline (250 μg/ml)-LB agar plates. One transformant for each mutant was grown overnight in tetracycline (250 μg/ml)-LB broth in order to allow expression of the cre recombinase. Plasmid pCM157 was then cured from the strains by successive passages on LB broth. Selected colonies were then screened for susceptibility to tetracycline (250 μg/ml) and gentamicin (30 μg/ml) and checked by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing. To asses the effect on growth rates of the mutants generated, the doubling times of cells growing exponentially in LB broth at 37°C and 180 rpm were determined by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on LB agar at 1-h intervals as previously described (21). Five independent experiments were performed for each of the mutants, and mean values (± standard deviations [SD]) were determined.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used or constructed in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and relevant characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Reference strain completely sequenced | Laboratory collection |

| PAΔdacB | PAO1 ΔdacB::lox dacB, encoding the nonessential PBP4 | 20 |

| PAΔC | PAO1 ΔampC::lox ampC, encoding the chromosomal β-lactamase AmpC | 21 |

| PAONB | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox nfxB, encoding the nefative regulator (NfxB) of MexCD-OprJ efflux pump | 23 |

| PAOMxD | PAO1 ΔmexD::lox mexD, encoding the MexD efflux pump component | 23 |

| PAOD1 | Spontaneous oprD null mutant (W65X) of PAO1 | 22 |

| PAOM | PAO1 ΔoprM::lox oprM, encoding the outer membrane protein component of MexAB-OprM and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps | This work |

| PAOMxR | PAO1 ΔmexR::lox mexR, encoding the negative regulator of MexAB-OprM efflux pump | This work |

| PANBdB | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔdacB::lox | This work |

| PANBMxD | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔmexD::lox | This work |

| PANBAC | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔampC::lox | This work |

| PANBOM | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔoprM::lox | This work |

| PAdBOM | PAO1 ΔdacB::lox ΔoprM::lox | This work |

| PANBdBOM | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔdacB::lox ΔoprM::lox | This work |

| PANBdBMxD | PAO1 ΔnfxB::lox ΔdacB::lox ΔmexD::lox | This work |

| JW | Wild-type P. aeruginosa clinical isolate | 35 |

| JWNB | JW ΔnfxB::lox | This work |

| GPP | Wild-type P. aeruginosa clinical isolate | 35 |

| GPPNB | GPP ΔnfxB::lox | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| XL-1 blue | F′::Tn10 proA+B+lac1qΔ(lacZ)M15 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 (Nalr) thi hsdR17 (rk− mk−) mcrB1 | Laboratory collection |

| S17.1 | RecA pro (RP4-2Tet::Mu Kan::Tn7) | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUCP24 | Gmr, pUC18-based Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vector | 32 |

| pUCPNB | Gmr, pUCP24 containing wild-type nfxB from PAO1 | This work |

| pEX100Tlink | Apr, sacB, pUC19-based gene replacement vector with an MCS | 26 |

| pUCGmlox | Apr, Gmr, pUC18-based vector containing the lox flanked aacC1 gene | 26 |

| pCM157 | Tcr, cre expression vector | 26 |

| pEXdacBGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of dacB::Gmlox | 20 |

| pEXACGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of ampC::Gmlox | 21 |

| pEXNBGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of nfxB::Gmlox | 23 |

| pEXMxDGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of mexD::Gmlox | 23 |

| pEXMxR | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of mexR | This work |

| pEXMxRGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of mexR::Gmlox | This work |

| pEXOM | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of oprM | This work |

| pEXOMGm | pEX100Tlink containing 5′–3′ flanking sequence of oprM::Gmlox | This work |

Nal, nalidixic acid; Kan, kanamycin; Gm, gentamicin; Ap, ampicillin; MCS, multiple-cloning site; Tc, tetracycline.

Table 2.

Primers used in this work

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′)a | PCR product size (bp) | Use | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACrnaF | GGGCTGGCCTCGAAAGAGGAC | 246 | Quantification of ampC mRNA | 14 |

| ACrnaR | GCACCGAGTCGGGGAACTGCA | |||

| MexB-U | CAAGGGCGTCGGTGACTTCCAG | 273 | Quantification of mexB mRNA | 24 |

| MexB-L | ACCTGGGAACCGTCGGGATTGA | |||

| MexD-U | GGAGTTCGGCCAGGTAGTGCTG | 236 | Quantification of mexD mRNA | 24 |

| MexD-L | ACTGCATGTCCTCGGGGAAGAA | |||

| MexF-U | CGCCTGGTCACCGAGGAAGAGT | 254 | Quantification of mexF mRNA | 24 |

| MexF-L | TAGTCCATGGCTTGCGGGAAGC | |||

| MexY-Fa | TGGAAGTGCAGAACCGCCTG | 270 | Quantification of mexY mRNA | 24 |

| MexY-Ra | AGGTCAGCTTGGCCGGGTC | |||

| RpsL-1 | GCTGCAAAACTGCCCGCAACG | 250 | Quantification of rpsL mRNA | 24 |

| RpsL-2 | ACCCGAGGTGTCCAGCGAACC | |||

| OprM-F3 | CACTACCGCCTGGGAACTC | 259 | Quantification of oprM mRNA | This work |

| OprM-R3 | GGTCGAGCGCGGAGGCG | |||

| nBF1BHI | TCGGATCCGCACCTCGGCGACCCGC | 523 | NfxB inactivation | 23 |

| nBR1HDIII | TCAAGCTTCGAGCATCTGCACCAGGTTG | |||

| nBF2HDIII | TCAAGCTTGCCTTCTTCCTGCGCGGAC | 434 | ||

| nBR2ERI | CGGAATTCCTGGGGGAGGTGTG | |||

| DACB-F-ERI | TCGAATTCCGACCATTCGGCGATATGAC | 571 | DacB inactivation | 20 |

| DACB-I-R-HD3 | TCAAGCTTGTCGCGCATCAGCAGCCAG | |||

| DACB-I-F-HD3 | TCAAGCTTGCCAGGGCAGCGTACCGC | 693 | ||

| DACB-R-BHI | TCGGATCCCGCGTAATCCGAAGATCCATC | |||

| AmpC-F-ERI | TCGAATTCGCGCGCAGGGCGTTCAG | 415 | AmpC inactivation | 21 |

| AmpC-I-R-HDIII | TCAAGCTTCGTCCTCTTACGAGGCCAG | |||

| AmpC-I-F-HDIII | TCAAGCTTCAGGGCAGCCGCTTCGAC | 432 | ||

| AmpC-R-BHI | TCGGATCCCAGGTTGGCATCGACGAAG | |||

| mxDF1BHI | TCGGATCCATCAAGCGGCCGAACTTCG | 446 | MexD inactivation | 23 |

| mxDR1HDIII | TCAAGCTTGGTGTCGCTGCGCTGAGC | |||

| mxDF2HDIII | TCAAGCTTCACCACGAGAAGCGCGGCTTC | 563 | ||

| mxDR2ERI | TCGAATTCAGCAGCGCTTCGCGGCCG | |||

| mxRF1 ERI | TCGAATTCAGCAGGGCCGGAACCAGTA | 453 | MexR inactivation | This work |

| mxRR1 HD3 | TCAAGCTTCAATACATGGACGTC | |||

| mxRF2 HD3 | TCAAGCTTGCGTGCATGACGAGTTGTTTG | 558 | ||

| mxRR2 BHI | TCGGATCCAGAAGAACCCGTCGGCCGA | |||

| OMF1ERI | TCGAATTCGATCGGTACCGGCGTGATC | 471 | OprM inactivation | This work |

| OMR1HDIII | TCAAGCTTACCGTCCACGCCGATCCG | |||

| OMF2HDIII | TCAAGCTTCTTCCCGAGCATCAGCCT | 522 | ||

| OMR2BHI | TCGGATCCAAGCCTGGGGATCTTCCTTC |

Sites for restriction endonucleases are underlined.

Cloning of nfxB and complementation studies.

For cloning nfxB, the PAO1 wild-type gene was PCR amplified using primers nBF1BHI and nBR2ERI (Table 2). The resulting PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated to plasmid pUCP24, digested with the same enzymes, to obtain plasmid pUCPNB, which was transformed into E. coli strain XL1-Blue. Transformants were selected on gentamicin (5 μg/ml)-MacConkey agar plates. The cloned DNA fragment was fully sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations generated during PCR amplification. Plasmids pUCPNB and pUCP24 (control) were then electroporated into PAO1 or the different nfxB mutants. Transformants were selected on gentamicin (30 μg/ml)-LB agar plates.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of the antipseudomonal agents ceftazidime, cefepime, cefotaxime, piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonam, imipenem, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, and tobramycin were determined using Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar plates and Etest strips in duplicate experiments.

Analysis of whole-genome gene expression.

Strains were grown in 10 ml of LB broth at 37°C and 180 rpm to the late log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 1). The cells were collected by centrifugation, and total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). RNA was dissolved in water and treated with 2 U of Turbo DNase (Ambion) for 30 min at 37°C to remove contaminating DNA. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of DNase inactivation reagent. Total RNA (10 μg) was checked by the use of an agarose gel prior to cDNA synthesis. cDNA synthesis, fragmentation, labeling, and hybridization were performed according to the Affymetrix GeneChip P. aeruginosa genome array expression analysis protocol. Three independent experiments were performed for each strain. Expression analysis was performed as previously described (33). Only transcripts showing increases or decreases that were higher than 2-fold were considered to represent differential expression results. In all cases, the value representing the posterior probability for differential expression (PPDE) was between 0.999 and 1.

Expression of resistance genes.

The levels of expression of ampC, mexB, mexD, mexY, mexF, and oprM were determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) following previously described protocols (14, 24). Total RNA was isolated as described above. A 50-ng sample of purified RNA was then used for one-step reverse transcription and real-time PCR amplification using a QuantiTect SYBR green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) and a SmartCycler II system (Cepheid). The primers listed in Table 2 were used for amplification of ampC, mexB, mexD, mexY, mexF, oprM, and rpsL (used as a reference to normalize the relative amounts of mRNA). In all cases, the mean values of relative mRNA expression obtained in at least three independent duplicate experiments were considered. For ampC induction experiments, cultures were incubated in the presence of imipenem (0.015 μg/ml).

Penicillin-binding protein (PBP) assays.

Late-log-phase (OD600 of 1) LB cultures (500 ml) were collected by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in 50 ml of buffer A (20 mM KH2PO4–140 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]). Cells were then sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Membranes containing the PBPs were isolated through two steps of ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C and suspension in buffer A. PBPs were then labeled with a 25 μM concentration of Bocillin FL fluorescent penicillin (36), separated through the use of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and visualized using a Bio-Rad FX Pro molecular imager.

OMP analysis.

A protocol adapted from those previously described (5) was followed. Briefly, late-log-phase (OD600 of 1) LB cultures (200 ml) were collected by centrifugation, washed, and suspended in 5 ml of buffer (10 mM Tris-Mg [pH 7.3]). Cells were then sonicated and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 15 min. Membranes were isolated through ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. Pellets were suspended in 10 ml of buffer (1% sarcosyl, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8]) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) were collected afterward through ultracentrifugation at 70,000 × g for 40 min, suspended in the same buffer, and ultracentrifuged again. OMPs were then suspended in water, separated using SDS-PAGE (11% acrylamide–0.2% bisacrylamide–0.2% SDS–0.375 M Tris [pH 8.8]), and visualized using Coomassie staining.

β-Lactamase assays.

Specific ß-lactamase activity (quantified as nanomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein) was determined spectrophotometrically, following established procedures (13), on culture supernatants, crude sonic extracts, and periplasmic fractions prepared as described elsewhere (10). Activities were determined at the early log phase (OD600 of 0.2), late log phase (OD600 of 1), and stationary phase (18 h of incubation). For normalizing total cell numbers in cultures from the different strains, CFU were enumerated by plating serial dilutions in LB agar. For AmpC induction experiments, cultures were incubated in the presence of imipenem (0.015 μg/ml). Mean values (± SD) of β-lactamase activity obtained from at least 3 independent experiments were considered in all cases.

Antimicrobial activity in biofilm growth.

Biofilms were formed following previously described protocols (23). Briefly, biofilms were grown by incubating peg lids (Nunc, Denmark) (at 24 h and 37°C under static conditions) in microtiter plates containing MH broth (approximately 2 × 108 cells/ml). Then, biofilms on peg lids were incubated for 24 h in MH broth supplemented with several concentrations of the tested antibiotics or left unsupplemented. Afterwards, biofilms were rinsed and transferred to MH broth by centrifugation (20 min, 1,000 rpm, 4°C). Serial 1/10 dilutions were then plated in MH agar to determine the number of viable cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

Antibiotic (hyper)susceptibility profile of nfxB mutants and reversion of resistance driven by AmpC hyperproduction.

As expected from reports of previous work (8), MexCD-OprJ overexpression in PAO1, driven by nfxB mutation, significantly increased the MICs of ciprofloxacin (16-fold) and cefepime (4-fold), which are known to be good substrates for the pump. On the other hand, it produced a significant decrease in the MICs of all other antipseudomonal agents, with the imipenem (16-fold) and tobramycin (4-fold) results being particularly noteworthy, but also of all other β-lactams tested (Table 3). Complementation with the wild-type nfxB gene, from the pUCPNB plasmid, fully restored the wild-type PAO1 susceptibility profile. The inactivation of nfxB in two genetically unrelated clinical strains yielded very similar susceptibility profiles, demonstrating that the observed phenotype was not specific to the PAO1 background (Table 3). Moreover, the inactivation of nfxB nearly reversed the resistance profile (cephalosporins, penicillins, and monobactams) of the AmpC-hyperproducer dacB (PBP4) mutant of PAO1 (Table 3). For example, the MICs of ceftazidime decreased from 24 μg/ml for the dacB mutant to 1.5 μg/ml (wild-type level) for the nfxB-dacB double mutant (Table 3). Complementation with the wild-type nfxB gene fully restored the parental dacB mutant susceptibility profile.

Table 3.

Susceptibility profiles of the studied P. aeruginosa strains

| Straina | MIC (μg/ml)b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAZ | FEP | CTX | PTZ | ATM | IMP | MER | CIP | TOB | |

| PAO1 (reference strain) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-nfxB | 0.5 | 6 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 1.5 | 0.25 |

| PAO1-dacB | 24 | 12 | >256 | 48 | 12 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-nfxB-dacB | 1.5 | 6 | 24 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 0.25 |

| PAO1-mexD | 1.5 | 1.5 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-nfxB-mexD | 1 | 1.5 | 8 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-nfxB-dacB-mexD | 24 | 12 | >256 | 48 | 12 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-ampC | 1 | 1.5 | 6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.094 | 1 |

| PAO1-nfxB-ampC | 0.75 | 6 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 1.5 | 0.25 |

| PAO1-oprM | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.094 | 0.008 | 0.25 |

| PAO1-nfxB-oprM | 0.5 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 1.5 | 0.19 |

| PAO1-dacB-oprM | 24 | 12 | >256 | 24 | 8 | 1.5 | 0.25 | 0.008 | 0.25 |

| PAO1-nxfB-dacB-oprM | 1.5 | 6 | 24 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 0.19 |

| JW (wild-type clinical isolate) | 1.5 | 3 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 1 |

| JW-nfxB | 1 | 32 | 8 | 3 | 1.5 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 0.38 |

| GPP (wild-type clinical isolate) | 1 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 |

| GPP-nfxB | 0.75 | 8 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 1.5 | 0.25 |

PAO1-nfxB (pUCPNB) and PAO1-nfxB-dacB (pUCPNB) showed the same MICs as PAO1 and PAO1-dacB, respectively.

CAZ, ceftazidime; FEP, cefepime; CTX, cefotaxime; PTZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; ATM, aztreonam; IMP, imipenem; MER, meropenem; CIP, ciprofloxacin; TOB, tobramycin.

The inactivation of mexD (efflux pump-encoding gene) in the nfxB mutant fully restored wild-type (PAO1) susceptibility, and the inactivation of mexD in the nfxB-dacB mutant fully restored the dacB phenotype (Table 3). Therefore, these findings indicate that the observed phenotypes relate directly to the overexpression of the efflux pump and not to the inactivation of its NfxB regulator. Real-time RT-PCR experiments showed that expression of ampC, mexB, mexY, mexF, and oprM was not significantly modified in the nfxB mutant compared to expression of wild-type PAO1. Moreover, while global transcriptome analysis revealed 34 genes (24 upregulated and 10 downregulated) with modified expression in the nfxB mutant, only those genes belonging to the mexC-mexD-oprJ operon had an obvious link to antibiotic susceptibility (Table 4). Therefore, these findings support the data presented above indicating that transcriptional regulation is not involved in the described NfxB phenotypes. Nevertheless, the effects on cell physiology or fitness of the modified gene expression patterns, including several involved in nitric oxide and iron or copper metabolism and quorum sensing, still need to be elucidated. Indeed, NfxB mutation also resulted in overall fitness reduction, as evidenced by the increased doubling times of growth of the nfxB mutant (42.7 ± 8.8) compared to wild-type PAO1 (26.9 ± 6.8), although, again, the results depended directly on overexpression of the efflux pump, since the inactivation of mexD in the nfxB mutant nearly compensated for the growth defect (doubling time of the nfxB-mexD mutant, 30.8 ± 7.1).

Table 4.

Gene loci showing modified expression (>2-fold change) in the nfxB mutant compared to the parental wild-type PAO1 strain as determined using Affymetrix GenChips

| Gene locus | Product | Fold expression change |

|---|---|---|

| PA0524-norB | Nitric oxide reductase subunit B | 11.85 |

| PA0523-norC | Nitric oxide reductase subunit C | 11.45 |

| PA4599-mexC | Resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) multidrug efflux membrane fusion protein MexC precursor | 11.00 |

| PA4598-mexD | Resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) multidrug efflux transporter MexD | 7.29 |

| PA4597-oprJ | Multidrug efflux outer membrane protein OprJ precursor | 5.53 |

| PA0525 | Probable denitrification NorD protein | 3.99 |

| PA3392-nosZ | Nitrous oxide reductase precursor | 3.12 |

| PA4386-groES | GroES protein | 3.09 |

| PA0518-nirM | Cytochrome c-551 precursor | 2.90 |

| PA0519-nirS | Nitrite reductase precursor | 2.89 |

| PA0200 | Hypothetical protein | 2.86 |

| PA0918 | Cytochrome b-561 | 2.71 |

| PA4919-pncB1 | Nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferase | 2.55 |

| PA0517-nirC | Probable c-type cytochrome precursor | 2.46 |

| PA1432-lasI | Autoinducer synthesis LasI protein | 2.38 |

| PA4385-groEL | GroEL protein | 2.28 |

| PA4687-hitA | Ferric iron-binding periplasmic HitA protein | 2.25 |

| PA3813-iscU | Probable iron-binding IscU protein | 2.25 |

| PA0516-nirF | Heme d1 biosynthesis NirF protein | 2.16 |

| PA4920-nadE | NH3-dependent NAD synthetase | 2.14 |

| PA4918 | Hypothetical protein | 2.06 |

| PA0024-hemF | Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, aerobic | 2.04 |

| PA5015-aceE | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | 2.01 |

| PA1431-rsaL | Regulatory RsaL protein | 2.01 |

| PA1555 | Probable cytochrome c | −2.88 |

| PA1557 | Probable cytochrome oxidase (cbb3-type) subunit | −2.85 |

| PA3361-lecB | Fucose-binding lectin PA-IIL | −2.79 |

| PA1556 | Probable cytochrome c oxidase subunit | −2.71 |

| PA0122 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −2.33 |

| PA4133 | Cytochrome c oxidase (cbb3-type) subunit | −2.33 |

| PA3790-oprC | Putative copper transport outer membrane porin OprC precursor | −2.21 |

| PA4217-phzS | Flavin-containing monooxygenase | −2.20 |

| PA1658 | Conserved hypothetical protein | −2.11 |

| PA3205 | Hypothetical protein | −2.03 |

Role of impairment of intrinsic efflux in NfxB phenotypes.

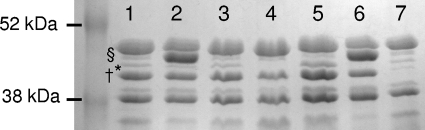

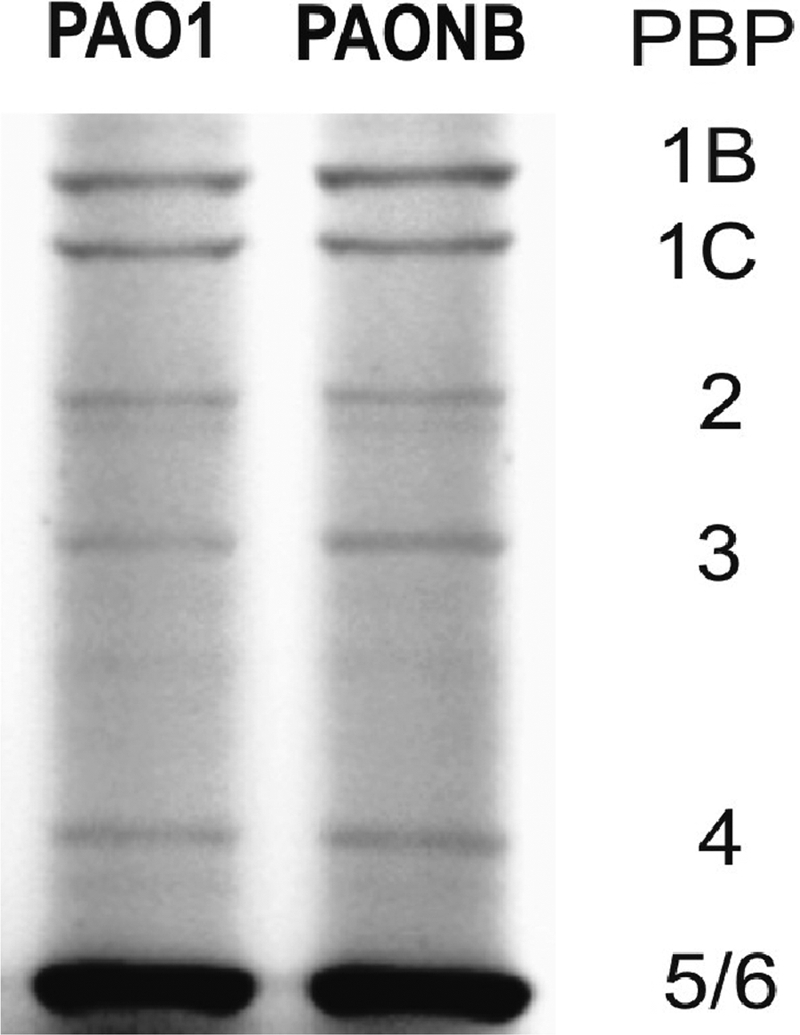

MexAB-OprM and MexXY-OprM efflux pumps play a central role in P. aeruginosa intrinsic resistance. Thus, hypersusceptibility of the nfxB mutant could well be driven by the impairment of these efflux pumps (8, 12). Indeed, despite the fact that transcription of oprM was not modified, in contrast to earlier observations (8), the outer membrane protein (OMP) profiles of the nfxB mutants confirmed the previously noted (8) reduced expression of OprM (Fig. 1, lane 1 versus lane 2). More informatively, susceptibility data clearly indicated that OprM was impaired (i.e., did not significantly contribute to resistance) in the nfxB mutant (Table 3). While the inactivation of oprM in PAO1 produced a remarkable decrease in the MICs of all antibiotics tested (except for imipenem), its inactivation in the nfxB (or nfxB-dacB) mutant did not have a significant effect on MICs, thus showing that OprM activity was already impaired in the nfxB mutants. Indeed, impairment of OprM in the nfxB mutant clearly explained the hypersusceptibility to tobramycin (substrate of MexXY-OprM) and to ceftazidime, cefotaxime, piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonam, and meropenem (substrates of MexAB-OprM), results that are consistent with previous observations (8, 12). On the other hand, it did not explain the imipenem hypersusceptibility, since oprM inactivation in PAO1 had a minimal (less than one 2-fold dilution) effect on the MIC of this antibiotic, which is consistent with previous studies showing that imipenem is not significantly extruded by any of these two pumps. Moreover, the efflux pumps were not involved in the reversion of PBP4-driven resistance in the nfxB-dacB mutant, since the inactivation of oprM in the dacB mutant did not reverse its resistance profile at all (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 1, OMP analysis also revealed that expression of the OprD carbapenem porin in the nfxB mutant was not significantly modified. Moreover, the PBP expression profile of the nfxB mutant was nearly identical to that of wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 2). These findings indicated that neither OprD nor PBPs are involved in the phenotype.

Fig. 1.

OMP profiles of wild-type PAO1 and different mutant derivatives. Lane 1, wild-type PAO1 (wild-type profile); lane 2, nfxB mutant (overexpression of OprJ, reduced expression of OprM); lane 3, nfxB-mexD mutant (wild-type profile); lane 4, oprM mutant (no expression of OprM); lane 5, mexR mutant (overexpression of OprM); lane 6, nfxB-oprM mutant (overexpression of OprJ, no expression of OprM); lane 7, oprD mutant (no expression of OprD). Bands corresponding to OprD (†), OprM (*), and OprJ (§) are indicated.

Fig. 2.

PBP expression profiles of wild-type strain PAO1 and its nfxB knockout mutant (PAONB).

Altered β-lactamase physiology in nfxB mutants.

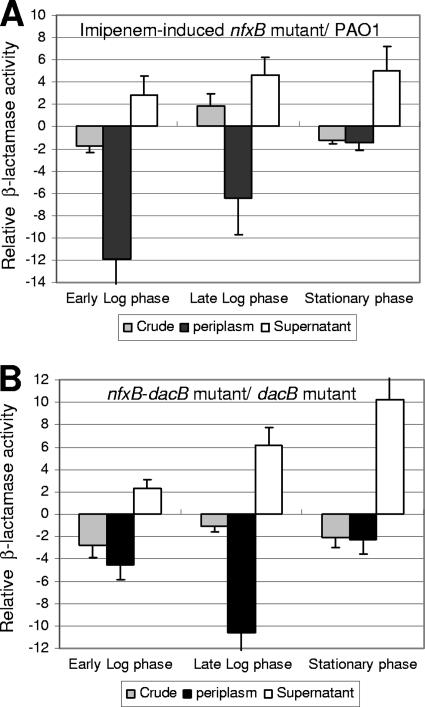

Data concerning the possible involvement of AmpC in the nfxB phenotype have remained elusive and controversial for years (16, 19, 34). As described above, the nfxB mutant showed no modified ampC expression. Moreover, as shown in Table 5, ampC in the nfxB mutant was still highly inducible in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of imipenem and still highly overexpressed in the nfxB-dacB double mutant. Similarly, crude (total) β-lactamase activity (basal or imipenem induced) was not significantly modified in the corresponding nfxB mutants (Table 5). These results should therefore support those of previous works concluding that AmpC is not involved (34), but a deeper analysis of AmpC physiology revealed that this is not actually the case. Indeed, a dramatic decrease in constitutive and induced periplasmic AmpC activity was noted in the nfxB mutants compared to the results seen with the respective parent strains (Table 5). Moreover, inducible (Fig. 3A) and constitutively overexpressed (Fig. 3B) AmpC activity in the periplasm was significantly impaired in the exponential-growth phase but not in the stationary phase. Obviously, the impairment of inducible and constitutively overexpressed AmpC activity in the location (periplasm) and growth phase (exponential growth) where it is expected to protect the drug targets (essential PBPs) should certainly explain the imipenem hypersusceptibility and reversion of PBP4-driven resistance. Accordingly, the susceptibility data of Table 3 with respect to the ampC mutants totally support the finding of impaired AmpC activity in the nfxB mutant. As would be expected, the inactivation of ampC in PAO1 dramatically reduced imipenem MICs (imipenem is a very strong AmpC inducer, despite its relative stability with respect to hydrolysis) but it had no major effect on susceptibility to other antipseudomonal β-lactams (very weak AmpC inducers, despite being efficiently hydrolyzed). On the other hand, the inactivation of ampC in the nfxB mutant did not further decrease the imipenem MICs, showing that AmpC activity was already impaired in the single nfxB mutant.

Table 5.

Basal and induced ampC expression and β-lactamase activity of crude, periplasmic, and culture supernatants for the studied mutants

| Strain |

ampC mRNAa |

β-Lactamase activityb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude |

Periplasmic |

Supernatant |

||||||

| Basal | Induced | Basal | Inducedc | Basal | Inducedc | Basal | Inducedc | |

| PAO1 | 1 | 19 ± 5.5 | 164 ± 36 (16 ± 5.9) | 4,714 ± 1,473 (353 ± 247) | 34 ± 5.1 (9.5 ± 2.6) | 590 ± 231 (210 ± 76) | NDd | 228 ± 135 (296 ± 176) |

| PAO1-nfxB | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 27 ± 6.5 | 148 ± 40 (13 ± 1.8) | 7,526 ± 1,269 (625 ± 391) | 13 ± 4.2 (4.5 ± 1.7) | 102 ± 25 (33 ± 17) | ND | 975 ± 345 (1,365 ± 483) |

| PAO1-nfxB-mexD | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 13 ± 2.0 | 227 ± 33 (28 ± 7.5) | 4,189 ± 346 (451 ± 279) | 37 ± 8.6 (13 ± 7.3) | 428 ± 85 (150 ± 49) | ND | 326 ± 243 (359 ± 267) |

| PAO1-dacB | 49 ± 9.5 | 72 ± 26 | 8,949 ± 2,911 (875 ± 254) | 13,278 ± 3,031 (1,006 ± 477) | 2,087 ± 495 (532 ± 114) | 3,525 ± 442 (745 ± 364) | 213 ± 77 (256 ± 92) | 1,124 ± 576 (1,574 ± 806) |

| PAO1-nfxB-dacB | 25 ± 5.4 | 58 ± 6.3 | 6,924 ± 2,635 (878 ± 470) | 15,746 ± 5,371 (1,709 ± 437) | 131 ± 20 (50 ± 19) | 361 ± 67 (116 ± 68) | 1,210 ± 234 (1,573 ± 304) | 1,850 ± 817 (2,590 ± 1,138) |

Results represent relative ampC mRNA levels compared to the levels seen with strain PAO1 under basal (noninduced) conditions.

Results represent picomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein (crude and periplasmic β-lactamase activity) or per milliliter (supernatant β-lactamase activity). β-Lactamase activity levels (expressed in picomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per min) per 109 CFU are shown in parentheses.

Induction experiments were carried out in the presence of imipenem at 0.015 mg/liter, corresponding to the lowest concentration of the antibiotic not compromising the growth rate of the nfxB mutant (ca. 0.25× MIC). The corresponding data for strain PAO1, determined using an equivalent (with respect to the MIC) concentration of imipenem (0.25 mg/liter [0.25× MIC]), were 60 for ampC mRNA, 7,152 for crude β-lactamase activity, 750 for periplasmic β-lactamase activity, and 425 for supernatant β-lactamase activity.

ND, β-lactamase activity was too low for accurate detection.

Fig. 3.

(A) Relative imipenem-induced crude, periplasmic, and culture supernatant AmpC activity levels of the nfxB mutant compared to parent wild-type PAO1 levels at different growth phases. (B) Relative basal (constitutive) crude, periplasmic, and culture supernatant AmpC activity levels of the nfxB-dacB mutant compared to parent dacB mutant levels at different growth phases.

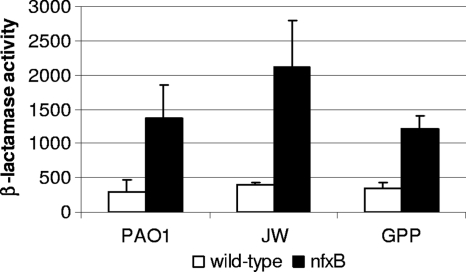

Additional analysis revealed that the imipenem-induced nfxB mutant and the nfxB-dacB mutant showed significantly higher AmpC activity on culture supernatants than their respective parent strains (Table 5, Fig. 3). This result further suggested that impairment of periplasmic AmpC activity in PAO1 does not result from a defective AmpC exportation from the cytoplasm to the periplasm but more likely from an altered outer membrane physiology produced by MexCD-OprJ overexpression, leading to AmpC leakage out of the cell. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, the increased leakage of AmpC resulting from nfxB inactivation was also observed for the clinical isolates JW and GPP, demonstrating the this phenomenon is not specific to PAO1.

Fig. 4.

Imipenem-induced AmpC activity (in picomoles of nitrocefin hydrolyzed per minute) per milliliter of supernatant from late-log-phase cultures (OD600 of 1 [adjusted to 109 CFU/ml]) of wild-type strains PAO1 (reference strain), JW, and GPP (clinical isolates) compared to that of their respective nfxB mutants.

Modified β-lactamase physiology in nfxB mutants is protective in biofilm growth.

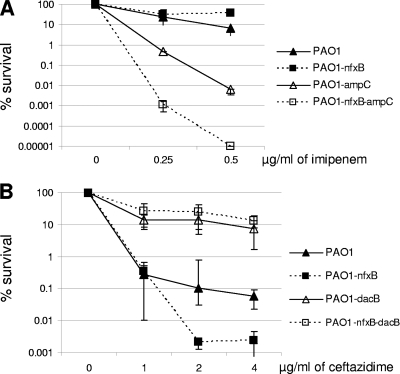

It seems obvious that failure to concentrate AmpC activity in the periplasm should dramatically limit the capacity of this enzyme to protect the PBP targets of β-lactam antibiotics at the individual cell level, but perhaps the expected outcome for cells growing as biofilm communities is less obvious, as they are surrounded by a thick extracellular matrix that could trap the leaked β-lactamase. Indeed, the results presented in Fig. 5 indicate that AmpC secreted by nfxB mutants is protective in biofilm growth. First, Fig. 5A shows that inducible AmpC expression is protective in the nfxB mutant since (i) imipenem hypersusceptibility was not observed and (ii) inactivation of ampC in the nfxB mutant markedly increased imipenem susceptibility. Second, Fig. 5B shows that constitutively overexpressed AmpC is also protective, since (i) ceftazidime resistance driven by AmpC overexpression (dacB inactivation) is not reversed through the inactivation of nfxB and (ii) the inactivation of dacB in the nfxB mutant sharply increased ceftazidime resistance. Thus, these results clearly indicate that resistance driven by inducible and constitutively overexpressed AmpC is not impaired when the nfxB mutants grow as biofilm communities, sharply contrasting with the results shown above for planktonically growing cells.

Fig. 5.

(A) Activity of imipenem (strong AmpC inducer but weakly hydrolyzed) against biofilms formed by wild-type strain PAO1 and its nfxB, ampC, and nfxB-ampC knockout mutants. (B) Activity of ceftazidime (very weak AmpC inducer but readily hydrolyzed) against biofilms formed by wild-type strain PAO1 and its nfxB, dacB, and nfxB-dacB knockout mutants. The results shown represent mean (± SD) relative survival percentages (corresponding to viable cells in treated versus nontreated biofilms) after 24 h of incubation in the presence of different concentrations of the antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Deciphering the complex interactions between resistance pathways is critical for guiding future strategies for the management of P. aeruginosa infections, through the identification of new targets or regimens (such as particular combinations of antimicrobial agents) to overcome resistance mechanisms. In this sense our results were encouraging, showing that these interactions among resistance pathways are not always synergistic. Indeed, we confirmed previous evidence (8, 12, 19) indicating that overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump (through the mutational inactivation of its negative regulator NfxB) may impair the backbone of related P. aeruginosa intrinsic resistance mechanisms, which include the major constitutive (MexAB-OprM) and inducible (MexXY-OprM) efflux pumps, together with the inducible chromosomal cephalosporinase AmpC. Moreover, we further demonstrated that it reversed the most relevant mechanism leading to acquired β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa, mutation-driven constitutive overexpression of AmpC. Our results indicated that impairment of intrinsic and acquired resistance occurs at the posttranscriptional level and depends on overexpression of the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump itself and not on the mutation of its negative regulator NfxB. While impairment of intrinsic pumps (MexAB-OprM and MexXY-OprM) upon MexCD-OprJ overexpression could well result from a compensatory balance of efflux machinery in the cell envelope, the explanation accounting for impairment of inducible and constitutive AmpC activity seemed less obvious. Indeed, neither ampC transcription nor crude (total) β-lactamase activity (basal or imipenem induced) was significantly modified in the nfxB mutants. Therefore, these results should have supported those of previous works concluding that AmpC is not involved (34), but a deeper analysis of AmpC physiology revealed that this was not actually the case. Indeed, a dramatic decrease in basal and induced periplasmic AmpC activity was noted in the nfxB mutants compared to the results seen with the respective parent strains. Obviously, the impairment of basal and induced AmpC activity in the location where it is expected to protect the drug targets (PBPs) should certainly explain the reversion of AmpC-driven resistance.

Additional analysis revealed that the imipenem-induced nfxB mutant and the nfxB-dacB mutant showed increased AmpC activity in culture supernatants. This result further indicates that impairment of periplasmic AmpC activity does not result from defective AmpC exportation to the periplasm from the cytoplasm but likely results from altered outer membrane physiology produced by MexCD-OprJ overexpression, leading to AmpC leakage from the cell. This claim is consistent with recent data showing that MexCD-OprJ overexpression produces major changes in membrane physiology, leading to a significantly modified exoproteome (30), and with the reduced growth rates documented for the nfxB mutant. Indeed, MexCD-OprJ expression has been shown to be inducible by a wide variety of membrane-damaging agents as part of the AlgU-controlled envelope stress response (6). From the therapeutic perspective, these results could delineate future strategies to be explored for combating antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa acute nosocomial infections, combining MexCD-OprJ inducers with classical antipseudomonal agents such as β-lactams or aminoglycosides.

The major drawback for the potential exploitation of the described antagonistic interaction between resistance mechanisms, as has occurred for many of our therapeutic approaches in the past, came from the differential bacterial physiology characteristics that occur in biofilm growth, a hallmark of chronic respiratory infections by P. aeruginosa. While it seemed obvious that failure to concentrate AmpC activity in the periplasm should dramatically limit the capacity of this enzyme to protect the targets (PBPs) of β-lactam antibiotics at the individual cell level, the expected outcome for cells growing as biofilm communities was less obvious, as they are surrounded by a thick extracellular matrix. Indeed, our results confirmed this fear, indicating that AmpC produced by nfxB mutants is fully protective in biofilm growth. Thus, our research strongly suggests that the release of AmpC into the matrix appears to protect biofilm communities against harmful β-lactams and is consistent with previous studies showing that extracellular AmpC plays a major role in biofilm resistance (1, 2). Unfortunately, this is bad news for the treatment of biofilm-driven infections that are indeed strongly linked to MexCD-OprJ overexpression, as evidenced by its (specific) high prevalence in chronic lung infection in cases of cystic fibrosis (11), its induction (7) and/or selection (23) during biofilm growth, and its involvement in early adaptation to the chronic setting (27), perhaps through mitigating acute virulence effectors (such as the type III secretion system) and promoting biofilm growth (15, 28). Finally, in addition to the therapeutic implications, our findings have important diagnostic consequences, since they denote that AmpC-driven resistance cannot be detected by conventional susceptibility tests performed in the frequent nfxB background of chronic infections, adding further evidence to support the studies showing a lack of correlation between susceptibility results and clinical responses (29).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jonathan McFarland for his help with correction of the English.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, and cofinanced by the European Development Regional Fund (ERDF; “A way to achieve Europe”), by the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD06/0008), and by grant PS09/00033.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bagge N., et al. 2004. Dynamics and spatial distribution of β-lactamase expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1168–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bagge N., et al. 2004. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms exposed to imipenem exhibit changes in global gene expression and β-lactamase and alginate production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1175–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costerton J. W., Stewart P. S., Greenberg E. P. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fajardo A., et al. 2008. The neglected intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens. PLoS One 3:e1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Filip C., Fletcher G., Wulf J. L., Earhart C. F. 1973. Solubilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli by the ionic detergent sodium-lauryl sarcosinate. J. Bacteriol. 115:717–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fraud S., Campigotto A. J., Chen Z., Poole K. 2008. MexCD-OprJ multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement in chlorhexidine resistance and induction by membrane-damaging agents dependent upon the AlgU stress response sigma factor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4478–4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gillis R. J., et al. 2005. Molecular basis of azithromycin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3858–3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gotoh N., et al. 1998. Characterization of the MexC-MexD-OprJ multidrug efflux system in ΔmexA-mexB-oprM mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1938–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Høiby N., Bjamsholt T., Givskov M., Molin S., Ciofu O. 2010. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:322–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Imperi F., Tiburzi F., Visca P. 2009. Molecular basis of pyoverdine siderophore recycling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:20440–20445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jalal S., Ciofu O., Hoiby N., Gotoh N., Wretlind B. 2000. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:710–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeannot K., et al. 2008. Resistance and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains overproducing the MexCD-OprJ efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2455–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Juan C., et al. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of β-lactam resistance mediated by AmpC hyperproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4733–4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Juan C., Moya B., Perez J. L., Oliver A. 2006. Stepwise upregulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal cephalosporinase conferring high level beta-lactam resistance involves three AmpD homologues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1780–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Linares J. F., et al. 2005. Overexpression of the multidrug efflux pumps MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN is associated with a reduction of type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 187:1384–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lister P. D., Wolter D. J., Hanson N. D. 2009. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:582–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Livermore D. M. 2002. Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:634–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lyczak J. B., Cannon C. L., Pier G. B. 2002. Lung infection associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:194–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masuda N., Sakagawa E., Ohya S., Gotoh N., Nishino T. T. 2001. Hypersusceptibility of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nfxB mutant to β-lactams due to reduced expression of the AmpC β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1284–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moya B., et al. 2009. β-lactam resistance response triggered by inactivation of a nonessential penicillin-binding protein. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moya B., Juan C., Alberti S., Perez J. L., Oliver A. 2008. Benefit of having multiple ampD genes for acquiring β-lactam resistance without losing fitness and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3694–3700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moya B., et al. 2010. Activity of a new cephalosporin, CXA-101 (FR264205), against β-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants selected in vitro and after antipseudomonal treatment of intensive care unit patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1213–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mulet X., et al. 2009. Azithromycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: bactericidal activity and selection of nfxB mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1552–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oh H., Stenhoff S., Jalal S., Wretlind B. 2003. Role of efflux pumps and mutations in genes for topoisomerases II and IV in fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microb. Drug Res. 9:323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Poole K. 2004. Efflux mediated multiresistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:12–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quénée L., Lamotte D., Polack B. 2005. Combined sacB-based negative selection and cre-lox antibiotic marker recycling for efficient gene deletion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biotechniques 38:63–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rau M. H., et al. 2010. Early adaptive developments of Pseudomonas aeruginosa after transition from the life in the environment to persistent colonization in the airways of human cystic fibrosis hosts. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1643–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sánchez P., et al. 2002. Fitness of in vitro selected Pseudomonas aeruginosa nalB and nfxB multidrug resistant mutants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:657–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith A. L., Fiel S. B., Mayer-Hamblett N., Ramsey B., Burns J. L. 2003. Susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates and clinical response to parenteral antibiotic administration: lack of association in cystic fibrosis. Chest 123:1495–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stickland H. G., Davenport P. W., Lilley K. S., Griffin J. L., Welch M. 2010. Mutation of nfxB causes global changes in the physiology and metabolism of P. aeruginosa. J. Proteome Res. 9:2957–2967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vincent J. L. 2003. Nosocomial infections in adult intensive-care units. Lancet 361:2068–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. West S. E., Schweizer H. P., Dall C., Sample A. K., Runyen-Janecky L. J. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Winsor G. L., et al. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa genome database and PseudoCAP: facilitating community-based, continually updated, genome annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 33(database issue):D338–D343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wolter D. J., Hanson N. D., Lister P. D. 2005. AmpC and OprD are not involved in the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates overexpressing the mexCD-oprJ efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4763–4766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zamorano L., Moyá B., Juan C., Oliver A. 2010. Differential β-lactam resistance response driven by ampD or dacB (PBP4) inactivation in genetically diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1540–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao G., Meier T. I., Kahi S. D., Gee K. R., Blaszczak L. C. 1999. BOCILLIN FL, a sensitive and commercially available reagent for detection of penicillin-binding proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1124–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]