Abstract

Aspergillus niger is a common clinical isolate. Multiple species comprise the Aspergillus section Nigri and are separable using sequence data. The antifungal susceptibility of these cryptic species is not known. We determined the azole MICs of 50 black aspergilli, 45 from clinical specimens, using modified EUCAST (mEUCAST) and Etest methods. Phylogenetic trees were prepared using the internal transcribed spacer, beta-tubulin, and calmodulin sequences to identify strains to species level and the results were compared with those obtained with cyp51A sequences. We attempted to correlate cyp51A mutations with azole resistance. Etest MICs were significantly different from mEUCAST MICs (P < 0.001), with geometric means of 0.77 and 2.79 mg/liter, respectively. Twenty-six of 50 (52%) isolates were itraconazole resistant by mEUCAST (MICs > 8 mg/liter), with limited cross-resistance to other azoles. Using combined beta-tubulin/calmodulin sequences, the 45 clinical isolates grouped into 5 clades, A. awamori (55.6%), A. tubingensis (17.8%), A. niger (13.3%), A. acidus (6.7%), and an unknown group (6.7%), none of which were morphologically distinguishable. Itraconazole resistance was found in 36% of the isolates in the A. awamori group, 90% of the A. tubingensis group, 33% of the A. niger group, 100% of the A. acidus group, and 67% of the unknown group. These data suggest that cyp51A mutations in section Nigri may not play as important a role in azole resistance as in A. fumigatus, although some mutations (G427S, K97T) warrant further study. Numerous cryptic species are found in clinical isolates of the Aspergillus section Nigri and are best reported as “A. niger complex” by clinical laboratories. Itraconazole resistance was common in this data set, but azole cross-resistance was unusual. The mechanism of resistance remains obscure.

INTRODUCTION

All black-spored aspergilli are grouped into Aspergillus section Nigri (12). Black aspergilli are often reported to be the third most frequently occurring Aspergillus spp. associated with invasive disease and aspergillomas (1, 9, 28, 29). Aspergillomas may subsequently produce oxalic acid in situ, which can result in renal complications (43). More commonly, however, the species cause otomycosis. In addition to their clinical significance, they also have agricultural importance as a common food spoilage organism (primarily grapes and coffee) (24, 26). The detection of ochratoxin, a potent nephrotoxin and potential carcinogen produced by some species in the section, has raised concerns about incorporation into the food chain (7, 31, 33). Black aspergilli are also used in biotechnology for the production of enzymes (such as amylases), acids (in particular, citric acid), and pectinases for fermentation (4, 54). Products of Aspergillus niger are considered generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the food industry (42).

Despite their importance, the taxonomy of Aspergillus section Nigri remains somewhat ill defined. It comprises a closely related group of organisms which are difficult to distinguish morphologically (1). As a result, in the clinical laboratory, reporting of all black aspergilli as A. niger on the basis of classical culture techniques (colony morphology, conidia size/ornamentation, etc.) is almost universal, yet isolates may not be A. niger but a closely related species. More recently, the results of non-culture-based methods have been utilized to differentiate between these species, including extrolite patterns, amplified fragment length polymorphisms, and restriction fragment length polymorphisms (11, 17, 41). However, the taxonomy of this section has principally been refined by DNA sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, beta-tubulin, calmodulin, and actin genes, and a polyphasic approach using these targets has been shown to be optimal (11, 26). Other targets have also been investigated, including pyruvate kinase, pectin lyase, intergenic spacer, and partial mitochondrial cytochrome b gene, with varying but often limited success (13, 41, 56, 57). Since the 1960s (37) there have been several suggested taxonomic revisions. Currently, there are 19 recognized taxa: A. aculeatinus, A. aculeatus, A. brasiliensis, A. carbonarius, A. costaricaensis, A. ellipticus, A. acidus (A. foetidus var. acidus [19, 23]), A. heteromorphus, A. homomorphus, A. ibericus, A. japonicus, A. lacticoffeatus, A. niger, A. piperis, A. sclerotiicarbonarius, A. sclerotioniger, A. tubingensis, A. uvarum, and A. vadensis (1, 41). Of these, several belong to the A. niger “aggregate” and are morphologically indistinguishable, including, e.g., A. brasiliensis, A. acidus, A. awamori, A. niger, and A. tubingensis (41). Unsurprisingly, there are limited taxonomic data available for clinical strains (3).

Azole resistance has been shown to be increasing and an important factor in the outcome of A. fumigatus infections (18, 45). The most commonly reported mechanism of azole resistance in A. fumigatus is alterations to the azole target protein (Cyp51Ap), as a result of mutations in the gene encoding it (cyp51A). Other reported mechanisms are overexpression of cyp51A and upregulation of efflux pumps, although the influence of these and other possible mechanisms has yet to be determined (18, 45, 53). Raised itraconazole MICs have also been reported in Nigri isolates, although susceptibility data are relatively scarce (10, 15, 20, 35, 44). To our knowledge, no reports describing resistance mechanisms in this complex have been published to date. Triazole breakpoints/epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) have been proposed for A. fumigatus (36, 38, 53) and more recently for A. niger (10).

The aims of this study were to identify the species of a clinical collection of black-sporing aspergilli using three molecular targets (the ITS, beta-tubulin, and calmodulin regions), identify any links between susceptibility and species, and investigate potential mechanisms of resistance in azole-resistant isolates by sequencing the cyp51A gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates.

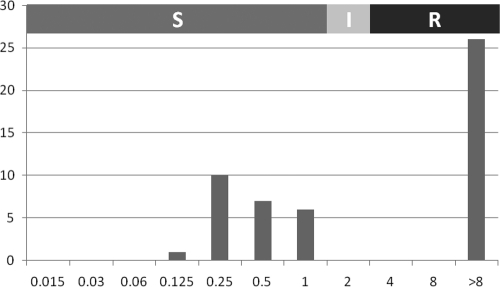

The itraconazole susceptibility and taxonomy of 50 black aspergilli were investigated: 45 were clinical isolates (all initially identified as A. niger using macro- and micromorphological techniques), 3 were from the Northern Regional Research Laboratory (NRRL; Peoria, IL), and 2 were from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA). Clinical strains were isolated between 1992 and 2007 and deposited in the Mycology Reference Centre, Manchester, United Kingdom, culture collection. These isolates were from 43 patients: 20 were isolated from ear swabs, 16 from respiratory samples, 6 from unknown specimens, and 3 from sterile sites (2 blood cultures and 1 mitral valve). Two samples revealed mixed macromorphology and were tested separately (suffixed a and b). A subset of 24 of these isolates was selected for further analysis to include at least 2 from each clade (Fig. 2); susceptibility to additional antifungal agents was tested, and the cyp51A gene was sequenced.

Fig. 2.

Maximum parsimony tree based on combined partial beta-tubulin and calmodulin sequences.

Susceptibility.

MICs were determined for itraconazole (Research Diagnostics Inc., Concord, MA) by a modified EUCAST (mEUCAST) method (the modification being a lower final inoculum concentration of 0.5 × 105 CFU/ml) (18, 46) and by Etest (bioMérieux, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mEUCAST method was used to facilitate comparison with prior A. fumigatus data (18). Candida krusei ATCC 6258 and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used as quality control strains, and all results were within the target range.

For the purposes of analysis, mEUCAST values of >8 mg/liter were classified as 16 mg/liter, and Etest values of >32 mg/liter were classified as 64 mg/liter.

A subset of 24 isolates was also tested against voriconazole (Pfizer Ltd., Sandwich, United Kingdom), posaconazole (Schering-Plough, NJ), econazole (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom), ravuconazole (Bristol-Myers Squibb, NY), and amphotericin B (Sigma) by both the mEUCAST (18) and EUCAST methods (46) in duplicate.

In the absence of clinical breakpoints for Aspergillus, proposed ECVs (10, 53) were applied to this data set for itraconazole (>2 mg/liter), voriconazole (>2 mg/liter), and posaconazole (>0.5 mg/liter).

Taxonomy.

DNA was extracted using an Ultraclean soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., Cambridge, United Kingdom) following the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR/sequencing primers used to amplify the ITS region, partial calmodulin, and partial beta-tubulin genes were ITS5 and ITS4 (55), CL1 and CL2A (25), and Bt2a and Bt2b (14), respectively. Forward primer ITS5 was chosen over ITS1, as ITS1 contains an additional guanine base (5′-TCCGTAGGGTGAACCTGCGG versus TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) in the primer region, leading to failed sequencing reactions. PCRs were performed in 25 μl, with 2 μM primer (4 μM for calmodulin), approximately 10 ng DNA, and 1× PCR Master Mix (providing final concentrations of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 0.625U Taq DNA polymerase; Promega Southampton, United Kingdom). Thermal cycling profiles for ITS and beta-tubulin amplification were as follows: 2 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 68°C for 10 min. The calmodulin thermal cycling profile was 94°C for 10 min, 35 cycles at 94°C for 50 s, 55°C for 50 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 7 min. Approximately 20 to 40 ng of purified PCR product and 4 μM primer were suspended in 10 μl water and sequenced by BigDye Terminator ready reaction mix (version 1.1) on an ABI 3730 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom).

Sequence alignments, including both exons and introns, for each molecular target were conducted using the ClustalW program (50) in the BioEdit package (version 7.0.5.3) (16). Subsequently, calmodulin and beta-tubulin sequences and then cyp51A sequences were combined and realigned. Additional GenBank sequences of Aspergillus section Nigri were incorporated for comparison (prefixed AJ/AY). Phylogenetic trees were prepared from alignments in the MEGA (version 4.1) program (47), using maximum parsimony and neighbor-joining methods. Gaps were treated as relevant for calculation of branch length. The support for each clade was determined by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications. Higher-resolution trees were made by realigning the combined sequence data from different genes.

Sequencing of cyp51A gene.

The entire coding region of the cyp51A gene was amplified. Initially, primers designed from the A. niger ATCC 1015 genome sequence were used; however, these primers produced insufficient or no yield in some isolates, despite PCR optimization. From these data, partial or complete cyp51A sequences were obtained for 12 isolates, from which degenerate primers were designed (Table 1). Twenty-five-microliter reaction mixtures were set up for each isolate with 1× PCR Master Mix (Promega), 0.5 μM primer, and approximately 10 ng genomic DNA. In addition, 5% dimethyl sulfoxide was added to some PCR mixtures where the yield was initially poor. The cyp51A thermal cycling profile for amplification was as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min, with a final step of 72°C for 10 min. Sequencing was conducted as described above in the “Taxonomy” section with the primers listed in Table 1 and 10 to 30 ng of purified PCR product. Mismatches in the cyp51A gene were investigated by alignment against sequences in the same clade from this data set, as no Nigri cyp51A sequences were available in GenBank.

Table 1.

PCR primers used to amplify the cyp51A gene in Aspergillus section Nigri

| Primera | Tmc (°C) | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Ancyp51A1F | 60.8 | TKT YCC TGC CTA CRG TCG CTTb |

| Ancyp51A2F | 60.8 | GTC CGA YGT TGT GTA CGA CTGb |

| Ancyp51A3F | 62.2 | GGA CAA AGA GAT TGC YCA CAT GAT Gb |

| Ancyp51A4F | 61.4 | GGA GAG ATG GTG GAC TAC GG |

| Ancyp51A5R | 54.7 | GAT GCT TAT TAC AAG GTA CTA G |

| Ancyp51A6R | 61.4 | CCT GGT GAG GCG AGT AGA AC |

| Ancyp51A7R | 61.2 | CTT MTC CTC GTC TGG GTT CTT Gb |

| Ancyp51A8R | 61.4 | CTG TAG ACC TCT TCC GCG CT |

PCR and sequencing primers. F, forward strand; R, reverse strand.

Degenerate primer, where K is G or T, Y is C or T, R is A or G, and M is A or C.

Tm, melting temperature.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the ITS, beta-tubulin, and calmodulin sequences are JF450750 to JF450799, JF450850 to JF450899, and JF450800 to JF450849, respectively. The GenBank accession numbers for cyp51A sequences determined in this study are JF450900 to JF450925.

RESULTS

Susceptibility.

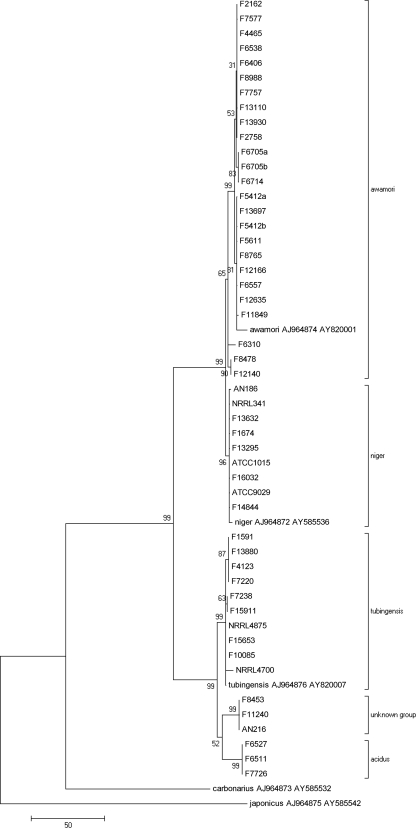

The distribution of itraconazole MICs by the mEUCAST method is shown in Fig. 1. Etest MICs (see the table in the supplemental material) were significantly different (generally lower) from mEUCAST MICs (paired samples t test, P < 0.001), with geometric means of 0.77 and 2.79 mg/liter, respectively. Isolates with itraconazole MICs of >8 mg/liter (26/50, 52%) by the mEUCAST method also showed raised Etest MICs: the resistant group had a geometric mean Etest MIC of 1.13 mg/liter (range, 0.32 to 64 mg/liter), whereas the geometric mean MIC was 0.5 mg/liter (range, 0.06 to 3 mg/liter) for those with mEUCAST MICs of <8 mg/liter. All 3 NRRL strains (NRRL341, NRRL4770, and NRRL4875) had high itraconazole MICs, whereas the MICs of both ATCC strains (ATCC 1015 and ATCC 9029) were low.

Fig. 1.

Itraconazole MICs of Aspergillus section Nigri from the Mycology Reference Centre Manchester culture collection and proposed ECVs (S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant). The MIC is shown on the x axis, and the number of isolates is shown on the y axis.

Susceptibilities determined for the subset of 24 isolates studied in more detail are shown in Table 2. As one might expect, MICs by the mEUCAST and EUCAST methods were generally comparable. Posaconazole and amphotericin B were the most active compounds in vitro, and itraconazole was the least active in this data set. Isolates with itraconazole MICs of >8 mg/liter by the mEUCAST method arguably showed reduced susceptibility to the other azoles. Comparing the itraconazole-resistant group to the itraconazole-susceptible group, the voriconazole geometric mean MICs were 2.08 and 0.91 mg/liter, respectively, and the posaconazole geometric mean MICs were 0.28 and 0.12 mg/liter, respectively. Of those resistant to itraconazole, 12% and 6% were resistant to voriconazole and posaconazole, respectively, and 59% and 6% fell into the intermediate range, respectively (53). Only one isolate (F12140) was highly cross-resistant to all azole drugs tested.

Table 2.

In vitro susceptibilities of a subset of 24 Aspergillus section Nigri isolates to commonly used antifungal agents

| Drug | Method | Cumulative % of isolates with MICs (mg/liter) of: |

Geometric mean MIC (mg/liter) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | >8 | |||

| Itraconazole | mEUCASTa | 4 | 8 | 17 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 100 | 5.82 | ||

| EUCAST | 4 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 100 | 7.55 | |||

| Voriconazole | mEUCAST | 4 | 58 | 92 | 92 | 92 | 100 | 1.63 | ||||

| EUCAST | 4 | 50 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 100 | 1.89 | |||||

| Posaconazole | mEUCAST | 4 | 8 | 33 | 92 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 0.22 |

| EUCAST | 8 | 25 | 88 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 0.23 | ||

| Ravuconazole | mEUCAST | 8 | 25 | 71 | 92 | 96 | 100 | 2.12 | ||||

| EUCAST | 8 | 17 | 71 | 92 | 92 | 100 | 2.31 | |||||

| Econazole | mEUCAST | 4 | 25 | 79 | 83 | 96 | 96 | 100 | 1.11 | |||

| EUCAST | 4 | 8 | 67 | 79 | 92 | 92 | 100 | 1.50 | ||||

| Amphotericin B | mEUCAST | 8 | 29 | 88 | 100 | 0.21 | ||||||

| EUCAST | 8 | 17 | 92 | 100 | 0.22 | |||||||

A significant color change of RPMI medium, indicating acidification, was observed during susceptibility testing of these isolates for all drugs by the mEUCAST, EUCAST (both RPMI broth), and Etest (solid RPMI agar) methods. This occurred to a greater extent in the broth microdilution wells containing lower drug concentrations, where there was more fungal growth. The higher inoculum of the EUCAST method than the mEUCAST method will likely accentuate the pH shift during incubation and, if relevant to the final MIC reading, could account for slightly higher MICs with the EUCAST method than the mEUCAST method.

Taxonomy.

The ITS region proved too similar to give sufficient resolution between this group of closely related organisms. Bootstrap values were poor (all values were 0), and branch lengths were short (data not shown). However, beta-tubulin and calmodulin were good targets in this setting, and the phylogenetic trees were largely in agreement. The calmodulin tree was more supported than the beta-tubulin tree, with an average bootstrap value of 98, compared to an average bootstrap value of 86 for the main clades.

Beta-tubulin and calmodulin sequences were then combined for each isolate and realigned. The resulting maximum parsimony tree is shown in Fig. 2. Bootstrap values are shown above the branches, and the number of nucleotide changes between taxa is represented by branch length. The topology of the neighbor-joining tree was comparable (data not shown). Some clades were more strongly supported than others, with less resolution on the A. awamori/A. niger branch.

Using the combined beta-tubulin/calmodulin data, the 45 clinical isolates grouped into 5 clades: a group of 25 A. awamori isolates (55.6%), a group of 8 A. tubingensis isolates (17.8%), a group of 6 A. niger isolates (13.3%), a group of 3 A. acidus isolates (6.7%), and a group of 3 unknown species (6.7%). Isolates from patients with repeat specimens (2 patients, 2 isolates each) and those separated due to mixed morphology (F5412a and F5412b, F6705a and F6705b) had identical sequences. Of these 36% A. awamori, 90% A. tubingensis, 33% A. niger, 100% A. acidus, and 67% unknown group isolates were resistant to itraconazole (MICs, ≥8 mg/liter by mEUCAST).

cyp51A sequencing.

The cyp51A gene in Aspergillus section Nigri is 1,539 bp in length, 9 bp shorter than cyp51A in A. fumigatus. A DNA sequence alignment of A. niger (ATCC 1015) and A. fumigatus revealed 70% identity (GenBank numbers JF450900 and AF338659, respectively). The intron in Nigri is 57 bases in length (A. tubingensis has 56 bases), positioned after codon 65.

An alignment of the cyp51A gene (data not shown) revealed consistent sequence differences between clades (discussed later), although there were a few isolates with notable nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms, as follows. Compared to a susceptible strain of the same species, azole-resistant A. awamori F7577 revealed alterations at codons 97 (K97T) and 512 (N512K). A. awamori F12140, the only strain in this study with high-level azole cross-resistance, had a mutation at codon 427 (G427S). NRRL4700 (also a resistant strain) differed from the other A. tubingensis strains tested by five nonsynonymous mutations (A9V, T321A, P413L, I503V, and L511S): at codon 9 it was identical to the A. niger/A. awamori group, while at codon 321 it was identical to all Nigri groups other than A. tubingensis. Conversely, no nonsynonymous mutations were found in resistant A. niger isolates. The cyp51A sequences of the three A. acidus isolates were identical to each other, although comparisons were hindered by the lack of a susceptible strain. All three isolates in the unknown species group had identical cyp51A sequences, including F11240, which was azole susceptible. This suggests that there were no resistance-linked cyp51A mutations in these clades.

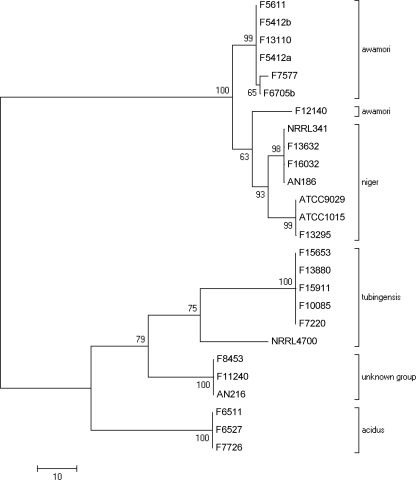

The cyp51A data revealed species-specific divergence and thus were reassessed as a taxonomic tool (Fig. 3). The A. niger clade divided into two groups differing by 11 base changes (6 synonymous), resulting in 4 amino acid alterations. Interestingly, the isolates in the first A. niger group (F13295, ATCC 1015, and ATCC 9029) were identical to A. awamori at codons 228 and 506, whereas those in the second group (F13632, F16032, NRRL341, and AN186) were identical to A. awamori at codons 507 and 511, so the evolutionary path is unclear. All A. niger isolates differed from A. awamori by a single amino acid at position 57. The cyp51A sequence of the unknown group differed from the sequences of the other clades at codons 140 and 413. Taxonomic findings from combined calmodulin and beta-tubulin sequencing (Fig. 2) suggest that F12140 is most closely related to A. awamori; however, by cyp51A sequencing (Fig. 3), the isolate was most similar to A. niger, although bootstrap values were low (<70) for all. This isolate differed from the A. awamori and A. niger groups by 19 and 12 base changes, respectively. Generally, A. tubingensis cyp51A sequences were identical, including the cyp51A sequence of F15911 (which was itraconazole susceptible by the mEUCAST method but resistant by the EUCAST method). NRRL4700 differed from the other five A. tubingensis sequences by 41 cyp51A base changes, which supports the combined calmodulin and beta-tubulin data (Fig. 2), suggesting that this isolate is dissimilar from the others in the clade.

Fig. 3.

Maximum parsimony tree based on cyp51A sequences.

Subsequently, cyp51A sequences were combined with partial calmodulin and beta-tubulin sequences and realigned (data not shown). Branch length and bootstrap values largely corroborated the combined calmodulin and beta-tubulin data, although with the addition of cyp51A sequences, the A. niger isolates split into two distinct groups. Furthermore, strain F12140 appears to be even more divergent from A. awamori and A. niger than it was previously.

DISCUSSION

There was a particularly high frequency of itraconazole resistance in this collection of black aspergilli, the reason for which remains unclear. Overall, 51% of clinical isolates (n = 45) but only 5% of A. fumigatus isolates from the same collection had itraconazole MICs of ≥8 mg/liter, determined using the same mEUCAST methodology (18). The mEUCAST method was used primarily to enable this comparison.

During this study ECVs proposed for the broth microdilution method were applied to the entire data set (10, 36, 38, 53), although much of that data set is based on A. fumigatus data, and they have yet to be clinically validated. MIC data collated during this study suggest that A. fumigatus itraconazole ECVs may be applicable to Aspergillus section Nigri, as the MIC distributions of the two complexes are similar (Fig. 1), although more data for black aspergilli are required to confirm this (36, 38, 53). Etest MICs were significantly lower than mEUCAST MICs. It is possible that the mEUCAST method is overestimating the MIC. However, where reduced susceptibility was observed, this was apparent by both techniques. This suggests not only that the high MICs were reproducible but also that ECVs are method dependent. Only 11% (5/45) of clinical isolates would have been itraconazole resistant by Etest using the same ECVs.

Interestingly, very little azole cross-resistance was observed in isolates with high itraconazole MICs in this study (Table 2), consistent with other some reports (10) but not others (3). This is in contrast to the findings for the comparable A. fumigatus data set, however (18). This could be mechanism related, or the ECVs may require further consideration, as other azole MICs were raised in itraconazole-resistant isolates but not necessarily in the resistant range.

Another potentially important observation was the color change of the RPMI medium during susceptibility testing of the Nigri group, which was far more than that seen with other Aspergillus species. RPMI contains the pH indicator phenol red; the more yellow that the medium is, the more acidic that the solution is. This factor could be critical for susceptibility testing in this setting, as pH has previously been shown to have a profound effect on MICs (21, 48, 49). In industry, A. niger is a citric acid producer, so it is not entirely surprising that the organism might produce acid during incubation. This phenomenon requires further study to explore the optimal susceptibility testing format in the A. niger complex.

The taxonomic work during this study was conducted to allow analysis of cyp51A sequences (discussed later) but revealed noteworthy findings. All isolates in this clinical collection were found to belong to the morphologically indistinguishable A. niger aggregate. Of these, only three are currently accepted Nigri species: A. acidus, A. niger, and A. tubingensis (40). A. awamori has been described to be a variety of A. niger (1, 57) and has only recently been suggested to represent a separate species (32). Assuming that A. awamori is a subgroup of A. niger, then approximately 70% of isolates were found to be A. niger. In the literature, A. niger is the most commonly reported human pathogen in this complex (39, 52). Reports of other Nigri species are scarce in this setting, although it is possible that these closely related organisms have been misidentified as A. niger using morphological techniques (1, 39). Similarly, A. niger predominated (68%) in a U.S. study (n = 19), with 32% being A. tubingensis (6), whereas in a recent Spanish report (n = 34), A. tubingensis was the most common (53%), followed by A. niger (38%) and A. acidus (9%) (3). Much of the molecular taxonomic work in the Nigri section has been conducted on plant pathogens due to their agricultural significance, although geographical environmental exposure may be medically relevant. A. niger, A. carbonarius, and A. tubingensis have been shown to be common causes of European grape spoilage (26, 30). The lack of wine production in the United Kingdom means that the frequency and environmental distribution of Nigri species are unknown.

This study revealed a discrete clade containing three isolates of unknown species. Calmodulin sequences were aligned against those in the extensive Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (Utrecht, The Netherlands) Nigri database and were found to be distinct from those of any currently recognized species. It is possible that these represent a new species, although this requires further investigation. Due to the lack of morphological differences within the A. niger aggregate, this is likely to require additional genome sequence data.

High itraconazole susceptibilities were more common in A. acidus, A. tubingensis, and the unknown group, as has been shown by other centers (3), suggesting that itraconazole resistance may be more common in certain Nigri species. There did not appear to be any link with the site of isolation and species. Isolates from all clades were cultured from a mix of specimens from lower respiratory, ear swab, and other sites. Species isolated from sterile sites were A. niger and A. awamori, both from blood culture, and an unknown group from a mitral valve.

ATCC and NRRL strains grouped as expected according to their species, with the exception of NRRL341. Isolate NRRL341 is held in the NRRL collection as an A. foetidus strain, and it is also held in the ATCC collection as the A. foetidus type strain (ATCC 16878). Results from this study suggest that NRRL341 is an A. niger strain, in accordance with the data of Peterson (34).

ITS sequences provided insufficient resolution (presumably due to the particularly close genetic relatedness of these isolates), as has been shown previously (3), whereas calmodulin and beta-tubulin were found to be good molecular taxonomic targets in this collection. Calmodulin sequencing traces were more problematic to decipher than those of either beta-tubulin or ITS due to background noise (presence of multiple peaks in the same position) and irregular spacing. One of the limitations of this study was the small numbers in some clades, reducing confidence in the phylogeny. Furthermore, GenBank sequences were added to the data set to help resolve identification, and it is theorized that up to 20% of GenBank submissions may be incorrect (5).

This is the first report, to our knowledge, describing cyp51A data in Aspergillus section Nigri. The alignment of cyp51A sequences suggests that the gene may be useful as a taxonomic target to distinguish between the Nigri clades. Results largely mirrored those obtained with calmodulin and beta-tubulin sequences. However, cyp51A is a large gene and requires four primer pairs to amplify the entire coding region. This provides full sequence data but increases costs and time; potentially specific regions of interest could be targeted for molecular typing or taxonomy studies.

Some isolates also revealed alterations which may be of potential interest in terms of resistance. The cyp51A gene of isolate F12140 (A. awamori) had an alteration at codon 427, which is positioned at the start of a highly homologous region containing the heme-binding site. Amino acid substitutions have been identified at this position in A. fumigatus; however, they have also been found in azole-susceptible isolates and so are unlikely to be associated with resistance in A. fumigatus (18). One mutation at codon 97 in A. awamori isolate F7577 is in a highly conserved region and all other Nigri isolates in this study had identical sequences at this codon, so it may be significant. Codon 98 mutations have been shown to be associated with azole resistance in A. fumigatus (22). Codon 512, however, is positioned in a variable region at the end of the gene just prior to the stop codon so is less likely to be significant.

The alterations identified have yet to be proven to be associated with azole resistance, although these preliminary data suggest that cyp51A mutations in Nigri may not play as important a role in azole resistance as in A. fumigatus. Perhaps cyp51A overexpression is more important, as demonstrated for some strains of A. fumigatus (2, 8, 22, 27), although cross-resistance might be expected more often if this were the primary resistance mechanism. Azole resistance has been engineered by overexpression of a cyp51A homologous gene from Penicillium italicum (51).

A high frequency of itraconazole resistance was found in our clinical isolates, although the clinical significance of this is unclear. Itraconazole resistance was more common in certain Nigri species, signifying that species identification may assist with the selection of antifungal therapy. Few, if any, cyp51A single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified to explain elevated MICs. Species identification using ITS sequences was found to be imprecise, but variations in the beta-tubulin, calmodulin, and cyp51A genes were all useful for the differentiation of this group of organisms. A. niger was the most common (assuming that A. awamori is a member of the A. niger subgroup). Several cryptic species, including an unknown group which may be a new species, were found, indicating that clinical reporting of A. niger isolate without molecular confirmation of identity is potentially misleading. We suggest that clinical laboratories report these isolates as “A. niger complex” if molecular identification is not undertaken. Despite their medical, agricultural, and industrial importance, the taxonomy of Aspergillus section Nigri remains relatively poorly defined. This is no doubt testament to the complexity of differentiation of these closely related species. Further study of resistance mechanisms and for an optimal susceptibility testing methodology is required in this group.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by David W. Denning's endowment fund. These studies were supported directly by the Fungal Research Trust and indirectly by the maintenance of the culture collection held at the Mycology Reference Centre Manchester.

We gratefully thank Scott Baker for providing the cyp51A sequence to enable primer design, Michael Anderson and Ahmed Albarrag for their technical advice, and Lea Gregson for assisting with the Etests. The NRRL strains were kindly donated by Stephen Peterson (National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, IL). Finally, thanks go to The University of Manchester sequencing facility for conducting sequencing reactions.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abarca M. L., Accensi F., Cano J., Cabanes F. J. 2004. Taxonomy and significance of black aspergilli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 86:33–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albarrag A., Anderson M., Sanglard D., Denning D. 2008. Upregulation of cyp51A gene as a mechanism of resistance in clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus (poster 178). Abstr. 3rd Advances against Aspergillosis Conf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alcazar-Fuoli L., Mellado E., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Cuenca-Estrella M., Rodriguez-Tudela J. L. 2009. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility patterns of species belonging to Aspergillus section Nigri. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4514–4517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker S. E. 2006. Aspergillus niger genomics: past, present and into the future. Med. Mycol. 44(Suppl 1):S17–S21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balajee S. A., et al. 2009. Sequence-based identification of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Mucorales species in the clinical mycology laboratory: where are we and where should we go from here? J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:877–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balajee S. A., et al. 2009. Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3138–3141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Battilani P., Pietri A. 2002. Ochratoxin A in grapes and wine. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 108:639–643 [Google Scholar]

- 8. da Silva Ferreira M. E., et al. 2004. In vitro evolution of itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus involves multiple mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4405–4413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Denning D. W. 1998. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:781–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Espinel-Ingroff A., et al. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the triazoles and six Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38-A2 document). J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:3251–3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frisvad J. C., et al. 2007. Secondary metabolite profiling, growth profiles and other tools for species recognition and important Aspergillus mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 59:31–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gams W., Christensen M., Onions A. H. S., Pitt J. I., Samson R. A. 1985. Infrageneric taxa of Aspergillus, p. 55–61 In Samson R. A., Pitt J. I. (ed.), Advances in Penicillium and Aspergillus systematics. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geiser D. M., et al. 2007. The current status of species recognition and identification in Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 59:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glass N. L., Donaldson G. C. 1995. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1323–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gomez-Lopez A., et al. 2003. In vitro activities of three licensed antifungal agents against Spanish clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3085–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall T. A. 1999. Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. 41:95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong S. B., Go S. J., Shin H. D., Frisvad J. C., Samson R. A. 2005. Polyphasic taxonomy of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Mycologia 97:1316–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howard S. J., et al. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1068–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kozakiewicz Z. 1989. Aspergillus species on stored products. Mycol. Papers 161:1–118 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maesaki S., et al. 2000. Antifungal activity of a new triazole, voriconazole (UK-109496), against clinical isolates of Aspergillus spp. J. Infect. Chemother. 6:101–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marr K. A., Rustad T. R., Rex J. H., White T. C. 1999. The trailing end point phenotype in antifungal susceptibility testing is pH dependent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1383–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mellado E., et al. 2007. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1897–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mogensen J. M., Varga J., Thrane U., Frisvad J. C. 2009. Aspergillus acidus from Puerh tea and black tea does not produce ochratoxin A and fumonisin B2. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 132:141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noonim P., Mahakarnchanakul W., Varga J., Frisvad J. C., Samson R. A. 2008. Two novel species of Aspergillus section Nigri from Thai coffee beans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:1727–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. O'Donnell K., Niremberg H., Aoki T., Cigelnik E. 2000. A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41:67–78 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oliveri C., Torta L., Catara V. 2008. A polyphasic approach to the identification of ochratoxin A-producing black Aspergillus isolates from vineyards in Sicily. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 127:147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Osherov N., Kontoyiannis D. P., Romans A., May G. S. 2001. Resistance to itraconazole in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus is conferred by extra copies of the A. nidulans P-450 14alpha-demethylase gene, pdmA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pappas P. G., et al. 2010. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1101–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perfect J. R., et al. 2001. The impact of culture isolation of Aspergillus species: a hospital-based survey of aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:1824–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perrone G., Gallo A., Susca A., Varga J. 2008. Aspergillus in grapes; ecology, biodiversity and genomics, p. 334 In Varga J., Samson R. A. (ed.), Aspergillus in the genomic era. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perrone G., et al. 2006. Ochratoxin A production and amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of Aspergillus carbonarius, Aspergillus tubingensis, and Aspergillus niger strains isolated from grapes in Italy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:680–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Perrone G., et al. 2010. Aspergillus niger contains the cryptic phylogenetic species A. awamori, abstr. P1.101. Abstr. 9th Int. Mycol. Cong. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Perrone G., et al. 2007. Biodiversity of Aspergillus species in some important agricultural products. Stud. Mycol. 59:53–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peterson S. W. 2008. Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus species using DNA sequences from four loci. Mycologia 100:205–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pfaller M., et al. 2010. Use of epidemiological cutoff values to examine 9-year trends in susceptibility of Aspergillus species to the triazoles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pfaller M. A., et al. 2009. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3142–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raper K. B., Fennell D. I., Austwick P. K. C. 1965. The genus Aspergillus. Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodriguez-Tudela J. L., et al. 2008. Epidemiological cutoffs and cross-resistance to azole drugs in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2468–2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Samson R. A., Hong S. B., Frisvad J. C. 2006. Old and new concepts of species differentiation in Aspergillus. Med. Mycol. 44(Suppl.):133–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Samson R. A., Houbraken J. A. M. P., Kuijpers A. F. A., Frank J. M., Frisvad J. C. 2004. New ochratoxin A or sclerotium producing species in Aspergillus section Nigri. Stud. Mycol. 50:45–61 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samson R. A., et al. 2007. Diagnostic tools to identify black aspergilli. Stud. Mycol. 59:129–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schuster E., Dunn-Coleman N., Frisvad J. C., Van Dijck P. W. 2002. On the safety of Aspergillus niger—a review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 59:426–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Severo L. C., Geyer G. R., Porto Nda S., Wagner M. B., Londero A. T. 1997. Pulmonary Aspergillus niger intracavitary colonization. Report of 23 cases and a review of the literature. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 14:104–110 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shi J. Y., et al. 2010. In vitro susceptibility testing of Aspergillus spp. against voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, amphotericin B and caspofungin. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 123:2706–2709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Snelders E., et al. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 5:e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 2008. EUCAST technical note on method for the determination of broth dilution MICs of antifungal agents for conidia-forming moulds. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:982–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. 2007. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24:1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Te Dorsthorst D. T., et al. 2004. Effect of pH on the in vitro activities of amphotericin B, itraconazole, and flucytosine against Aspergillus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3147–3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Te Dorsthorst D. T., Verweij P. E., Meis J. F., Mouton J. W. 2005. Relationship between in vitro activities of amphotericin B and flucytosine and pH for clinical yeast and mold isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3341–3346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. van den Brink H. J., van Nistelrooy H. J., de Waard M. A., van den Hondel C. A., van Gorcom R. F. 1996. Increased resistance to 14 alpha-demethylase inhibitors (DMIs) in Aspergillus niger by coexpression of the Penicillium italicum eburicol 14 alpha-demethylase (cyp51) and the A. niger cytochrome P450 reductase (cprA) genes. J. Biotechnol. 49:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Varga J., et al. 2000. Genotypic and phenotypic variability among black aspergilli, p. 510 In Samson R. A., Pitt J. I. (ed.), Integration of modern taxonomic methods for Penicillium and Aspergillus classification. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 53. Verweij P. E., Howard S. J., Melchers W. J., Denning D. W. 2009. Azole-resistance in Aspergillus: proposed nomenclature and breakpoints. Drug Resist. Updat. 12:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ward O. P., Qin W. M., Dhanjoon J., Ye J., Singh A. 2006. Physiology and biotechnology of Aspergillus. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 58:1–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal rRNA genes for phylogenetics, p. 315–322 In Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. (ed.), PCR protocols: guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yokoyama K., Wang L., Miyaji M., Nishimura K. 2001. Identification, classification and phylogeny of the Aspergillus section Nigri inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200:241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zanzotto A., Burruano S., Marciano P. 2006. Digestion of DNA regions to discriminate ochratoxigenic and non-ochratoxigenic strains in the Aspergillus niger aggregate. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 110:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.