Abstract

A novel streptogramin A, pleuromutilin, and lincosamide resistance determinant, Vga(E), was identified in porcine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ST398. The vga(E) gene encoded a 524-amino-acid protein belonging to the ABC transporter family. It was found on a multidrug resistance-conferring transposon, Tn6133, which was comprised of Tn554 with a stably integrated 4,787-bp DNA sequence harboring vga(E). Detection of Tn6133 in several porcine MRSA ST398 isolates and its ability to circularize suggest a potential for dissemination.

TEXT

In Gram-positive bacteria, cross-resistance to pleuromutilins and streptogramins A and decreased susceptibility to lincosamides have been attributed to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters encoded by vga genes (7, 11, 16). To date, six vga genes have been described: vga(A) (3), vga(A)LC (24), vga(A)v (13, 14), vga(B) (2), vga(C) (16), and vga(D). While vga(D) was identified on a plasmid in Enterococcus faecium (15), all of the other genes were found on plasmids or transposons in staphylococci.

The use of antibiotics has likely contributed to the selection for such resistance genes. In pig husbandry, virginiamycin, a combination of virginiamycin M (type A streptogramin) and virginiamycin S (type B streptogramin), was extensively used in feed as a growth promoter for 30 years prior to being banned in Europe in 1999 (1, 26). However, antibiotics are still widely used in piggeries to prevent and treat bacterial infectious diseases. Several drugs, such as the pleuromutilins tiamulin and valnemulin and the lincosamide clindamycin, are among those antibiotics that are administrated through medicated feed (6).

During the monitoring of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the nasal cavities of pigs at slaughterhouses in Switzerland in 2009 and 2010, 90% of the MRSA isolates were resistant to tiamulin (25). While one-third of these tiamulin-resistant MRSA isolates harbored the vga(A)v gene, the remaining isolates did not contain any of the known vga genes (25). In the present study, we characterized a new streptogramin A, pleuromutilin, and lincosamide resistance gene, vga(E). Further, we demonstrated its localization on a new multidrug resistance-conferring Tn554-like transposon, Tn6133, in MRSA sequence type 398 (ST398).

Detection of vga(E) and Tn6133.

The MRSA ST398 spa type t034 strain IMD49-10 (Table 1) was tested for the presence of transferable virginiamycin M1-tiamulin resistance by electrotransformation and conjugation. No transfer between S. aureus IMD49-10 and S. aureus 80CR5 (Fusr Rifr) (10) occurred during filter mating experiments (27) using selection on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar containing 100 μg/ml rifampin, 25 μg/ml fusidic acid, and either 5 μg/ml virginiamycin M1 or 5 μg/ml tiamulin. All antibiotics used in the study were purchased by Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. However, transformants were obtained after the electroporation of competent S. aureus RN4220 cells (29) with plasmid DNA extracted from IMD49-10 by using the NucleoBond Xtra midi kit (Macherey-Nagel). RN4220 transformants were selected on NYE (1% casein hydrolysate, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% sodium chloride [29]) agar plates containing 10 μg/ml virginiamycin M1. In addition to displaying virginiamycin M1 resistance, the transformants also displayed resistance to tiamulin, erythromycin, clindamycin, and spectinomycin as determined by a broth dilution method (8) using Sensititre staphylococci plate EUST (Trek Diagnostics Systems, East Grinstead, England) and handmade microtiter plates for virginiamycin M1, spectinomycin, tiamulin, and clindamycin (Table 1). PCR analysis revealed that the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) resistance gene erm(A) and the spectinomycin resistance gene ant(9)-Ia were transferred from IMD49-10 DNA into the RN4220 transformant strain SSC49-10, suggesting the possible presence of a Tn554-like element. In transposon Tn554, the two antibiotic resistance genes erm(A) and ant(9)-Ia are flanked by three transposase genes (tnpA, tnpB, and tnpC) on one side and by an open reading frame (ORF) of unknown function (orf) on the other side (Fig. 1) (21). Tn554 is known to integrate with high frequency into the unique att554 site of the S. aureus chromosome (18, 22).

Table 1.

Antibiotic resistance genes and susceptibility of S. aureus strains to macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramin, aminocyclitol, and pleuromutilin antibiotics as determined by broth dilution

| Strain | Characteristics and resistance genesa | Source and/or reference | MIC of antibiotics (μg/ml)b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIR M1 | Q-D | TIA | CLI | ERY | SPC | |||

| IMD49-10 | Tn6133 [ant(9)-Ia erm(A) vga(E)]; blaZ dfr(G) mecA str tet(K) tet(M) | 25, this study | 256 | 2 | >256 | 16 | >8 | >256 |

| SSC49-10 | RN4220 with Tn6133 [ant(9)-Ia erm(A) vga(E)] | This study | 256 | 2 | >256 | 4 | 4 | >256 |

| RN4220/pBSSC12 | RN4220 with vga(E) cloned into pBUS1; pBSSC12 [vga(E) tet(L)] | This study | 128 | 1 | 256 | 4 | ≤0.25 | 128 |

| RN4220/pBUS1 | RN4220 with cloning vector pBUS1 [tet(L)] | 28, this study | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.25 | 64 |

| RN4220 | Recipient strain | 17 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.12 | ≤0.25 | 64 |

Antibiotic resistance genes and functions are as follows: ant(9)-Ia, spectinomycin adenylnucleotidyltransferase; blaZ, β-lactamase; dfr(G), dihydrofolate reductase for trimethoprim resistance; erm(A), macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B rRNA methylase; mecA, penicillin-binding protein PBP 2a; str, streptomycin aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferase; tet(K) and tet(L), tetracycline efflux; tet(M), tetracycline ribosomal protection; vga(E), streptogramin A-pleuromutilin-lincosamide ABC transporter.

Antibiotics: ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; SPC, spectinomycin; Q-D, quinupristin-dalfopristin; TIA, tiamulin; VIR M1, virginiamycin M1.

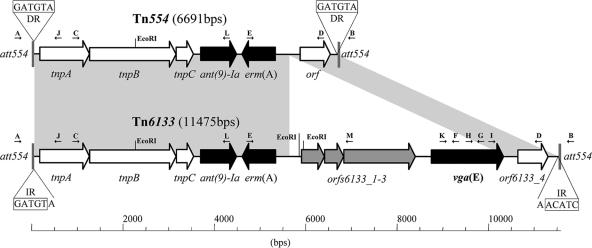

Fig. 1.

Comparison of S. aureus transposons Tn554 (GenBank accession no. X03216) and Tn6133 (GenBank accession no. FR772051). Gray areas indicate regions with more than 99% identity between the two transposons. Chromosomal insertion site att554 (K02985) is indicated by gray vertical lines, and the nucleotide repeats at the junction belonging either to the att554 site (left) or the transposon (right) are shown in boxes (DR, direct repeat; IR, inverted repeat). The positions and orientations of open reading frames (ORFs) are represented by arrows. Antibiotic resistance genes ant(9)-Ia, erm(A), and vga(E) (the novel gene; bold) are indicated by black arrows. The gene cluster (orf6133_1 to orf6133_3) encoding two small proteins of unknown function and a new putative serine recombinase (encoded by orf6133_3) are indicated by gray arrows. Genes coding for transposition function (tnpA, tnpB, and tnpC) or unknown function (orf [Tn554] or orf6133_4 [Tn6133]) are indicated by white arrows. Primers used in this study are represented by small black arrows: A, att554-F; B, att554-R; C, tnpA-F; D, orf-R; E, erm(A)-R; F, vga(E)-R4; G, vga(E)-R3; H, vga(E)-F7; I, vga(E)-R; J, tnpA-R; K, vga(E)-F6; L, ant(9)-Ia-R; M, orf6133_3-R8. Cleavage sites for the restriction endonuclease EcoRI are indicated.

The presence of a Tn554-like element in IMD49-10 and SSC49-10 was confirmed by PCR amplification of the two regions flanking the ant(9)-Ia and erm(A) gene cluster by using primers specific for tnpA (tnpA-F, 5′-AGATTAGGTCACGCACATG) and ant(9)-Ia [ant(9)-Ia-R, 5′-CTTAACGAGTGCTTTCACC] as well as primers specific for erm(A) [erm(A)-R, 5′-TTAGTGAAACAATTTGTAACTATTG] and the orf gene of Tn554 (orf-R, 5′-TAGATTTGGCAAGATCGAGC) (Fig. 1). PCRs were performed using the Roche Expand Long Template PCR system with an extension time of 5 min and an annealing temperature of 50°C. S. aureus BM3318 containing Tn554 was used as a control (13). A 3.3-kb fragment was obtained for the 5′ part of the transposon, as in Tn554; however, from the 3′ part of the transposon, a 6.3-kb fragment, instead of the expected 1.5-kb fragment, was amplified.

DNA sequencing of the 6.3-kb fragment revealed the presence of a new vga gene, which was named vga(E) (MLS nomenclature, http://faculty.washington.edu/marilynr/). From here, the complete nucleotide sequence of the transposon was obtained for IMD49-10 and SSC49-10 by sequencing both strands of the regions spanning the vga(E) gene with the 5′ and 3′ parts of the integration site for Tn554 (att554) (ABI 3100 genetic analyzer; Applied Biosystems). Both regions were amplified using one primer pair specific for the 5′ att554 (att554-F, primer 1 in reference 14, 5′-GTTCGATTGTACATCCACG) and vga(E) [vga(E)-R4, 5′-TAGCTCCTGTTATTCTTGC; extension time, 8 min; annealing temperature, 50°C; PCR product, 9.4 kb] and another primer pair specific for vga(E) [vga(E)-R, 5′-GGGTAGGTTGAGTTTGGAG] and the 3′ att554 (att554-R, primer 12 in reference 14, 5′-CCCGCTTCTACAAGACTGG; extension time, 2 min; annealing temperature, 50°C; PCR product, 1.4 kb) (Fig. 1).

Characterization of Tn6133.

The assembled sequences revealed a new transposon of 11,475 bp that was designated Tn6133 (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/eastman/tn/). Tn6133 consisted of the Tn554 sequence with an insertion of a new 4,787-bp sequence between positions 5745 and 5746 of Tn554 (Fig. 1). The Tn554-like DNA of Tn6133 was nearly identical to the Tn554 sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. X03216), except for four deletions at positions C5555, G5561, G5591, and G5740 (Tn554 numbering) and an additional guanine in the 5784-to-5788 G stretch; all variations were located in noncoding regions. The inserted 4,787-bp DNA segment had asymmetric ends that lacked either inverted or direct terminal repeats. We did not observe a transposon that had lost the 4,787-bp insert [primers erm(A)-R and orf-R] or a circular form of the insert only in IMD49-10 or SSC49-10 by PCR [primers orf6133_3-R8 (5′-GTTACGCTTCTTGCTAAAGC) and vga(E)-R]. This suggests that the additional DNA sequence was stably integrated into the Tn554 sequence. The ability of Tn6133 to circularize in IMD49-10 and SSC49-10 cells was demonstrated by PCR using two primers directed outwards from Tn6133 [primers vga(E)-F7 (5′-ATGAAAGAATAGCAATCCCAG) and tnpA-R (5′-ACCACCCTCATACATAAGC)]. Transposition of Tn554 includes the formation of a circular form that precedes Tn554 integration into the chromosome (20). The sequence at the transposon ends varied with respect to the attachment site, and the core sequence of the att554 integration site (5′-GATGTA; Fig. 1) is usually found at the right-end junction of Tn554-like transposons (20, 23). Tn6133 displayed a variant right-end sequence of 5′-AACATC when integrated into the IMD49-10 chromosome; however, the core sequence of 5′-GATGTA was observed when Tn6133 was integrated into the SSC49-10 att554 site or when it circularized in IMD49-10 and SSC49-10 cells. These characteristics as well as the specific integration into the att554 site indicate that Tn6133 is likely to be mobilized by the transposases TnpA, TnpB, and TnpC analogously to Tn554 (4).

As predicted using NCBI's ORF-Finder software, the new 4,787-bp sequence contained four ORFs. Of these, orf6133_1 and orf6133_2 coded for small proteins of 165 and 138 amino acids (aa), respectively, while orf6133_3 encoded a putative recombinase of 522 aa. The new vga(E) gene encoded a 524-aa protein related to the Vga family of ABC transporters. Amino acid sequence comparison using the BLAST algorithm revealed that deduced amino acid sequence from orf6133_3 shared 75% overall identity with a site-specific recombinase of Clostridium difficile (ZP_06891069) and Streptococcus mitis (YP_003446815) and 74% overall identity with a putative DNA recombinase of Bacillus cereus (NP_976747). Conserved domain analysis (CD search software; NCBI) indicated that the deduced amino acid sequence from orf6133_3 possessed all of the catalytic residues of a serine recombinase (R34 and S36 [motif A] and S106, R107, and R110 [motif C] [12]). The N-terminal catalytic domain was followed by a cysteine-containing motif (aa 328 to 369) with a consensus sequence, LX5CX2CG/(E)X13–27Y/(W)XCX2–21C [residues in parentheses indicate deviations from consensus sequence found in Vgα(E)], and a small Leu/Iso/Val-rich region (aa 493 to 503) which characterize members of the large serine recombinase family (31). These site-specific recombinases have the ability to catalyze excision and integration of DNA elements and are represented by the phiC31 integrase, TnpX, and TndX recombinases (19, 30, 33).

Characterization of Vga(E).

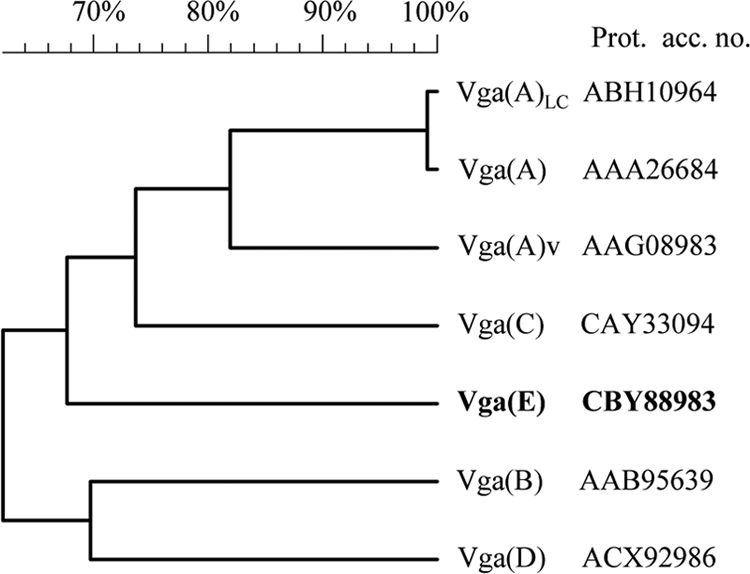

The Vga(E) protein shared less than 65% DNA identity and less than 56% amino acid identity with known Vga determinants (Table 2). In a phylogenetic tree, Vga(E) was situated in a separate branch within the cluster containing the different Vga(A) proteins and Vga(C) (Fig. 2). Vga proteins belong to class 2 of the ABC transporters that contain two nucleotide-binding domains in the same polypeptide chain with no transmembrane domains (5). Duplicate conserved amino acid motifs required for ATP binding and hydrolysis were found in Vga(E). Overall, the following components and motifs were found in the amino acids of Vga(E): the Walker A motif sequence GxxxxGKT (x represents any amino acid) at aa 36 to 43 and 304 to 311, the Walker B motif sequence followed immediately by a glutamate residue hhhhD(E) (h represents a hydrophobic amino acid) at aa 99 to 104 and 404 to 409 (32), the ABC transporter signature motif at aa 79 to 83 (KSGGE) and 384 to 388 (LSGGE), the invariant glutamine of the lid region at aa Q71 and Q337, and the conserved histidine of the switch region at aa H133 and H438 (9). Consistent with the case for other Vga transporters, no hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain was identified in Vga(E).

Table 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid identities of the new Vga(E) determinant compared with related Vga determinants that confer resistance to streptogramins A, pleuromutilins, and lincosamides

| Determinant | GenBank accession no. | % identitya |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vga(A) |

Vga(A)LC |

Vga(A)v |

Vga(B) |

Vga(C) |

Vga(D) |

Vga(E) |

|||||||||

| nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | ||

| Vga(A) | M90056 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 83 | 81 | 57 | 46 | 66 | 64 | 57 | 48 | 63 | 53 |

| Vga(A)LC | DQ823382 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 81 | 59 | 45 | 67 | 63 | 60 | 48 | 64 | 53 | ||

| Vga(A)v | AF186237 | 100 | 100 | 55 | 45 | 67 | 66 | 58 | 50 | 63 | 54 | ||||

| Vga(B) | U82085 | 100 | 100 | 56 | 45 | 61 | 53 | 53 | 41 | ||||||

| Vga(C) | FN377602 | 100 | 100 | 56 | 53 | 61 | 55 | ||||||||

| Vga(D) | GQ205627 | 100 | 100 | 57 | 48 | ||||||||||

| Vga(E) | FR772051 | 100 | 100 | ||||||||||||

Sequence alignment was performed with EMBOSS pairwise alignment algorithms (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/emboss/align/; needle global alignment of two sequences [matrices were Blosum62 for proteins and DNAfull for DNA; open gap penalty, 10.0; gap extension penalty, 0.5]). nt, nucleotides.

Fig. 2.

Relatedness between Vga(E) (bold) and other Vga proteins. The dendrogram was constructed by alignment of the amino acid sequences using BioNumerics 5.10 (Applied Maths) with the following comparison settings: unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA); pairwise open gap penalty, 100%; unit gap penalty, 0%; fast algorithm minimum match sequence, 2; maximum number of gaps, 9; gapcost, 0%.

vga(E)-mediated antibiotic resistance was demonstrated by the expression of vga(E) from its own promoter by using the Escherichia coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pBUS1, which lacks promoter sequences (28). The vga(E) gene, along with 512 bp upstream DNA of the start codon, was amplified by PCR from IMD49-10 by using primers vga(SalI)-F2 (5′-catgtcgaCAACGGATTGAAGAAATGACA) and vga(XbaI)-R2 (5′-cattctagATTCCCTACTATGAGTCACTA). These primers were supplemented with linkers (lowercase) that contained a SalI or XbaI restriction site (underlined) to facilitate cloning into pBUS1. The resulting plasmid, pBSSC12, was electroporated into S. aureus RN4220 cells (29). When present in S. aureus RN4220 cells on the pBSSC12 plasmid or on Tn6133, the vga(E) gene conferred a minimum of a 6-fold increase in resistance to virginiamycin M1 and at least 5-fold and 10-fold increases in resistance to clindamycin and tiamulin, respectively. In contrast, RN4220 cells alone and RN4220 cells harboring the empty pBUS1 vector remained susceptible to these antibiotics (Table 1). Decreased susceptibility to the streptogramin quinupristin-dalfopristin was also noted for RN4220 cells containing vga(E) (Table 1). MICs for cefoxitin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, fusidic acid, gentamicin, kanamycin, linezolid, mupirocin, penicillin, rifampin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, trimethoprim, and vancomycin remained unchanged (data not shown).

Distribution of Tn6133 in MRSA.

Eighteen tiamulin-resistant MRSA ST398-t034 isolates recovered from pigs raised in different geographical regions of Switzerland tested positive for the vga(E) gene by PCR using primers vga(E)-F6 (5′-GAAATATGGGAAATAGAAGATGG) and vga(E)-R3 (5′-TGATTCTCTAACCACTCTTC) with an annealing temperature of 52°C. All isolates harbored Tn6133 as determined by EcoRI restriction endonuclease analysis of the PCR products covering the regions situated between vga(E) and both ends of Tn6133. The left part of Tn6133 was amplified with the primers tnpA-F and vga(E)-R3 and the right part with the primers vga(E)-F6 and orf-R (Fig. 1). Each of the obtained profiles was identical to the profiles of the sequenced IMD49-10 strain, emphasizing the spread of Tn6133 in MRSA in Switzerland.

Once again, our discovery demonstrated the ability of bacteria to acquire new antibiotic resistance genes via mobile genetic elements to adapt to the antimicrobial pressures common in pig husbandry. The presence of a new gene in livestock-associated MRSA ST398 that confers resistance toward antibiotics that are mainly used in animals provides further evidence that the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry contributes to the selection of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of Tn6133 and parts of its flanking att554 sites has been deposited in the EMBL database under accession number FR772051.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Endimiani and Adam Roberts for scientific advice, Carlos Abril for help with BioNumerics analysis, and Brigitte Berger-Bächi and Sibylle Burger for providing the pBUS1 vector.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acar J., Casewell M., Freeman J., Friis C., Goossens H. 2000. Avoparcin and virginiamycin as animal growth promoters: a plea for science in decision-making. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6:477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allignet J., El Solh N. 1997. Characterization of a new staphylococcal gene, vgaB, encoding a putative ABC transporter conferring resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds. Gene 202:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allignet J., Loncle V., El Sohl N. 1992. Sequence of a staphylococcal plasmid gene, vga, encoding a putative ATP-binding protein involved in resistance to virginiamycin A-like antibiotics. Gene 117:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bastos M. C., Murphy E. 1988. Transposon Tn554 encodes three products required for transposition. EMBO J. 7:2935–2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouige P., Laurent D., Piloyan L., Dassa E. 2002. Phylogenetic and functional classification of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) systems. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 3:541–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Büttner S., Flechtner O., Müntener C., Kuhn M., Overesch G. 2009. Bericht über den Vertrieb von Antibiotika in der Veterinärmedizin und das Antibiotikaresistenzmonitoring bei Nutztieren in der Schweiz (ARCH-VET). Federal Veterinary Office and Swissmedic, Bern, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chesneau O., Ligeret H., Hosan-Aghaie N., Morvan A., Dassa E. 2005. Molecular analysis of resistance to streptogramin A compounds conferred by the Vga proteins of staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:973–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2009. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 8th ed., vol. 29, no. 2 Approved standard M07–A8 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davidson A. L., Chen J. 2004. ATP-binding cassette transporters in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:241–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Engel H. W., Soedirman N., Rost J. A., van Leeuwen W. J., van Embden J. D. 1980. Transferability of macrolide, lincomycin, and streptogramin resistances between group A, B, and D streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 142:407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gentry D. R., et al. 2008. Genetic characterization of Vga ABC proteins conferring reduced susceptibility to pleuromutilins in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4507–4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grindley N. D., Whiteson K. L., Rice P. A. 2006. Mechanisms of site-specific recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:567–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haroche J., Allignet J., Buchrieser C., El Solh N. 2000. Characterization of a variant of vga(A) conferring resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2271–2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haroche J., Allignet J., El Solh N. 2002. Tn5406, a new staphylococcal transposon conferring resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds including dalfopristin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2337–2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jung Y. H., et al. 2010. Characterization of two newly identified genes, vgaD and vatG, conferring resistance to streptogramin A in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4744–4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kadlec K., Schwarz S. 2009. Novel ABC transporter gene, vga(C), located on a multiresistance plasmid from a porcine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3589–3591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kreiswirth B. N., et al. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krolewski J. J., Murphy E., Novick R. P., Rush M. G. 1981. Site-specificity of the chromosomal insertion of Staphylococcus aureus transposon Tn554. J. Mol. Biol. 152:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucet I. S., et al. 2005. Identification of the structural and functional domains of the large serine recombinase TnpX from Clostridium perfringens. J. Biol. Chem. 280:2503–2511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murphy E. 1990. Properties of the site-specific transposable element Tn554, p. 123–135 In Novick R. P. (ed.), Molecular biology of the staphylococci. VCH Publishers, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murphy E., Huwyler L., de Freire Bastos M. D. C. 1985. Transposon Tn554: complete nucleotide sequence and isolation of transposition-defective and antibiotic-sensitive mutants. EMBO J. 4:3357–3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murphy E., Löfdahl S. 1984. Transposition of Tn554 does not generate a target duplication. Nature 307:292–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy E., Phillips S., Edelman I., Novick R. P. 1981. Tn554: isolation and characterization of plasmid insertions. Plasmid 5:292–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Novotna G., Janata J. 2006. A new evolutionary variant of the streptogramin A resistance protein, Vga(A)LC, from Staphylococcus haemolyticus with shifted substrate specificity towards lincosamides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4070–4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Overesch G., Büttner S., Rossano A., Perreten V. 2011. The increase of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the presence of an unusual sequence type ST49 in slaughter pigs in Switzerland. BMC Vet. Res. 7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perreten V. 2003. Use of antimicrobials in food-producing animals in Switzerland and the European Union (EU). Mitt. Lebensm. Hyg. 94:155–163 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perreten V., Kollöffel B., Teuber M. 1997. Conjugal transfer of the Tn916-like transposon TnFO1 from Enterococcus faecalis isolated from cheese to other Gram-positive bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 20:27–38 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rossi J., Bischoff M., Wada A., Berger-Bächi B. 2003. MsrR, a putative cell envelope-associated element involved in Staphylococcus aureus sarA attenuation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2558–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schenk S., Laddaga R. A. 1992. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 73:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith M. C., Brown W. R., McEwan A. R., Rowley P. A. 2010. Site-specific recombination by phiC31 integrase and other large serine recombinases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38:388–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith M. C., Thorpe H. M. 2002. Diversity in the serine recombinases. Mol. Microbiol. 44:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walker J. E., Saraste M., Runswick M. J., Gay N. J. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang H., Mullany P. 2000. The large resolvase TndX is required and sufficient for integration and excision of derivatives of the novel conjugative transposon Tn5397. J. Bacteriol. 182:6577–6583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]