Abstract

Both T helper interleukin 17 (IL-17)-producing cells (Th17 cells) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been found to be increased in human tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE); however, the possible interaction between Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE remains to be elucidated. The objective of the present study was to investigate the distribution of Th17 cells in relation to Tregs, as well as the mechanism of Tregs in regulating generation and differentiation of Th17 cells in TPE. In the present study, the numbers of Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE and blood were determined by flow cytometry. The regulation and mechanism of CD39+ Tregs on generation and differentiation of Th17 cells were explored. Our data demonstrated that the numbers of Th17 cells and CD39+ Tregs were both increased in TPE compared with blood. Th17 cell numbers were correlated negatively with Tregs in TPE but not in blood. When naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured with CD39+ Tregs, Th17 cell numbers decreased as CD39+ Treg numbers increased, and the addition of the anti-latency-associated peptide monoclonal antibody to the coculture reversed the inhibitory effect exerted by CD39+ Tregs. This study shows that Th17/Treg imbalance exists in TPE and that pleural CD39+ Tregs inhibit generation and differentiation of Th17 cells via a latency-associated peptide-dependent mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

One-third of the world's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and in 2008, 9.4 million new active tuberculosis cases were reported with 1.8 million tuberculosis-linked deaths (32). Despite the enormous number of people infected, only about 10% of affected individuals show evidence of symptoms and develop the clinical disease. Infection with M. tuberculosis elicits humoral and cellular immune responses that normally control bacterial burden. Although immune response against tuberculosis exists, M. tuberculosis is seldom eradicated, suggesting that their immune response is not protective against active disease (31). Since the identification of T-helper type 1 (Th1) or Th2 lineage more than 2 decades ago, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and T helper interleukin 17 (IL-17)-producing cells (Th17 cells) have been added to the “portfolio” of Th cells. Tregs depress the T cell-mediated immune responses to the protective mycobacterial antigen during active tuberculosis in humans (11). Th17 cells have been reported to contribute to the adaptive immune response to M. tuberculosis in exposed persons and in patients with tuberculosis (22). Moreover, Tregs can modulate Th17 responses even in patients with latent M. tuberculosis infection (3).

Tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE) is caused by a severe delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction in response to the rupture of a subpleural focus of M. tuberculosis infection (15). An accumulation of lymphocytes, especially CD4+ T cells, in TPE has been well documented (18). In previous studies, we have demonstrated that increased Tregs are found in TPE and that these Tregs are recruited into pleural space induced by chemokine CCL22 (21, 33). More recently, Wang et al. (30) demonstrated that Th17 cells were significantly increased in TPE compared with blood and that the mRNA and protein expression levels of IL-17 and IL-6 were significantly increased, whereas the expression level of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) was decreased in TPE.

TGF-β is a key cytokine involving in regulating the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells and Tregs. TGF-β is synthesized in cells as a pro-TGF-β precursor. Following homodimerization, pro-TGF-β is cleaved into two fragments: the C-terminal homodimer corresponds to mature TGF-β, while the N-terminal homodimer is latency-associated peptide (LAP) (9). Mature TGF-β and LAP remain noncovalently bound to each other in a complex called latent TGF-β. Latent TGF-β is inactive because LAP prevents mature TGF-β from binding to its receptor and hence from transducing a signal (14).

In the present study, we investigated the distribution of Th17 cells in relation to CD39+ Tregs. We were also prompted to investigate whether CD39+ Tregs are capable of suppressing generation and differentiation of Th17 cells in TPE, as well as whether LAP is involved in such a possible suppression.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects.

The study protocol was approved by our institutional review boards for human studies, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The patients were included subsequently if the examinations of pleural fluid and/or biopsy specimens established a diagnosis of TPE.

Twenty-three patients (age range, 21 to 64 years) were proven to have TPE, as evidenced by growth of M. tuberculosis from pleural fluid or by demonstration of granulomatous pleurisy on a closed pleural biopsy specimen in the absence of any evidence of other granulomatous diseases (Table 1). All TPE patients were anti-human immunodeficiency virus antibody (Ab) negative and were recruited from Department of Internal Medicine, Wuhan Institute of Tuberculosis Prevention and Control. After antituberculosis chemotherapy, the resolution of TPE and clinical symptoms was observed in all patients with TPE.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with TPE

| Patient no. | Age (yr) | Sex | PPDa test positive | Growth of M. tuberculosis | Histological confirmation with pleural biopsy specimen | HIV status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 2 | 27 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 3 | 21 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 4 | 48 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 5 | 39 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 6 | 61 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 7 | 58 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 8 | 52 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 9 | 36 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 10 | 42 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 11 | 48 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 12 | 36 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 13 | 40 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 14 | 64 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 15 | 55 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 16 | 29 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 17 | 47 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 18 | 53 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 19 | 39 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 20 | 44 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 21 | 33 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| 22 | 37 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| 23 | 50 | F | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

PPD, purified protein derivative.

The patients were excluded if they had accepted any invasive procedures directed into the pleural cavity, if any chest trauma was occurred within 3 months prior to their hospitalization, or if there was a pleural effusion of origin unknown. At the time of sample collection, none of the patients had received any antituberculosis therapy, corticosteroids, or other nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs.

Sample collection and processing.

Five-hundred-milliliter TPE samples from each patient were collected in heparin-treated tubes, through a standard thoracocentesis technique within 24 h after hospitalization. Twenty milliliters of blood was drawn simultaneously. TPE specimens were immersed in ice immediately and were then centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5 min. The cell pellets of TPE were resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), and mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) to determine the T cell subsets within 1 h. A pleural biopsy was performed when the results of pleural fluid analysis were suggestive of tuberculosis.

Flow cytometry.

The expression markers on T cells from TPE and blood were determined by flow cytometry after surface or intracellular staining with anti-human-specific Abs conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), PEcy5.5, PEcy7, peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-cy5.5, or allophycocyanin (APC). These human Abs included anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO, anti-LAP, anti-IL-17, and anti-FOXP3 monoclonal Abs (MAbs), which were purchased from BD Biosciences or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Intracellular staining for IL-17 or FOXP3 was performed on T cells stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (1 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) for 5 h and then stained with anti-IL-17 or -FOXP3 conjugated with phycoerythrin (eBioscience). Flow cytometry was performed on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) Canto II (BD Biosciences) using BD FCSDiva software and FCS Epress 4 (De Novo Software) software.

Cell isolation.

Bulk CD4+ T cells from TPE and blood were isolated by negative selection (by depletion of CD8+, CD11b+, CD16+, CD19+, CD36+, and CD56+ cells) with the Untouched CD4+ cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After isolation of bulk CD4+ T cells, the naïve CD4+ T cells (CD45RA+ CD45RO−) were further purified by EasySep enrichment kits (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total isolated cells were of >98% viability as determined by trypan blue staining. The purity of naïve CD4+ T cells was >97%, as measured by flow cytometry.

CD4+ T cells were also stained with CD4-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD25-phycoerythrin, and CD39-fluorescein isothiocyanate (eBiosciences), and CD4+ CD25high CD39+ T cells were sorted using a Beckman Coulter cell sorter. The purity of the sorted populations was >97%.

Generation and differentiation of Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE.

Purified naïve CD4+ T cells (5 × 105) were cultured in 1 ml of complete medium containing human IL-2 (2 ng/ml) in 48-well plates and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (OKT3; 1 μg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) MAbs for 7 days. The exogenous cytokines used were IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (100 ng/ml), and TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml). Recombinant human IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and TGF-β1, were purchased from R&D Systems. In some experiments, designated numbers of CD39+ Tregs were added into the culture. To demonstrate that LAP was responsible for the inhibitive effects of CD39+ Tregs, blocking experiments were performed by adding 500 ng/ml of anti-LAP MAb (clone 27235) or mouse IgG irrelevant isotype control (R&D Systems) into the coculture.

Alternatively, purified naïve CD4+ T cells labeled with fluorescent dye CFSE (carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester) (Molecular Probes) by incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 μM CFSE for 10 min at 37°C were used, and the fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as medians (25th to 75th percentiles) or mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparisons of the data between different groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance. For variables in TPE and in corresponding blood, paired data comparisons were made using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The correlations between variables were determined by Spearman rank correlation coefficients. Analysis was completed with SPSS version 16.0 statistical software (Chicago, IL), and P values of <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Increased proportion of Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE.

We are not showing the cytological and biochemical characteristics in TPE here, since these data have been reported previously (13, 16), and similar results were observed in the present study.

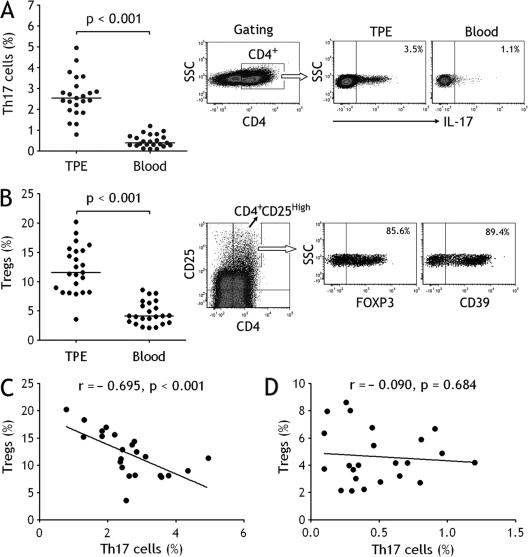

We first used flow cytometry to identify Th17 cells in CD4+ T cells in TPE and blood. It was found that percentages of Th17 cells represented the higher values in TPE (median, 2.5%; 25th to 75th percentiles, 2.0% to 3.1%), showing significant increases in comparison with those in blood (0.4%; 0.3% to 0.7%) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1 A). We next identified CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cell subsets with expression both FOXP3 and CD39 in TPE and blood. Consistent with our previous studies (21), Treg numbers in TPE (11.6%; 8.2% to 15.3%) were much higher than those in blood (4.2%; 3.0% to 6.3%), (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1B). We also noted that some pleural CD4+ T cells were CD39+ IL-17+ cells (∼ 2%).

Fig. 1.

Th17 cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) increased in tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE). (A) Comparisons of Th17 cell percentages in TPE and blood (n = 23). Horizontal bars indicate medians. The percentages of Th17 cells were determined by flow cytometry. The representative flow cytometric dot plots of Th17 cells in TPE and in blood are shown. (B) Comparisons of Treg percentages in TPE and blood (n = 23). Horizontal bars indicate medians. The percentages of Tregs were determined by flow cytometry. The subset of CD4+ CD25high T cells was identified by flow cytometry for determining the expression of FOXP3 and CD39; data for 1 representative donor of 23 patients with TPE are shown. Tregs correlated negatively with Th17 cells in TPE (C) but not in blood (D) (both n = 23). Correlations were determined by Spearman rank correlation coefficients.

We further noted that Tregs correlated negatively with Th17 cells in TPE (r = −0.695, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C). However, Tregs did not correlate with Th17 cells in blood (r = −0.090, P = 0.684) (Fig. 1D).

Impacts of cytokines on Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE.

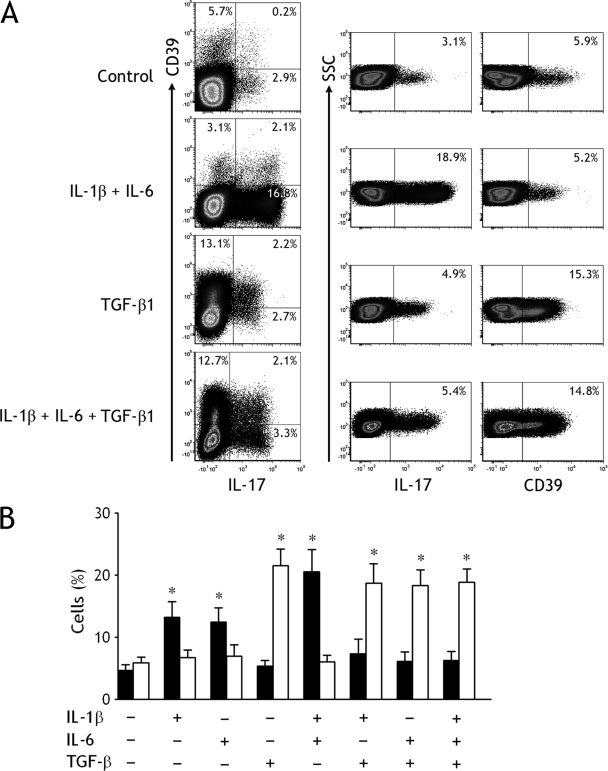

Some proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TGF-β, have been found in TPE (10, 12, 23, 30). To evaluate the contribution of these cytokines to the increases of pleural Th17 cells and Tregs, we isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from TPE and cultured them in the presence of IL-1β, IL-6, and/or TGF-β. When IL-2-containing medium served as the baseline control, IL-1β, or IL-6, but not TGF-β, could promote the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2). The combination of IL-1β plus IL-6 significantly increased the percentage of Th17 cells at higher extents compared with any single one of them, whereas TGF-β could reduce the increased percentage of Th17 cells stimulated by IL-1β and/or IL-6. In contrast, TGF-β was capable of promoting the differentiation of Tregs during the 7-day culture, and IL-1β and/or IL-6 did not affect the increase in Treg numbers induced by TGF-β (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Generation and differentiation of Th17 cells and CD39+ Tregs from tuberculous pleural effusion regulated by different cytokines. (A) The representative dot plots of freshly isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from tuberculous pleural effusion were determined for expression of IL-17 and CD39 by flow cytometry (top). The representative dot plots of Th17 cells and CD39+ Tregs detected in naïve CD4+ T cells after culturing in the presence of both IL-1β and IL-6 (second from top). The representative dot plots of Th17 cells and CD39+ Tregs detected in naïve CD4+ T cells after culturing in the presence of TGF-β1 (second from bottom). The representative dot plots of Th17 cells and CD39+ Tregs detected in naïve CD4+ T cells after culturing in the presence of IL-1β, IL-6, and TGF-β1 (bottom). (B) The mean ± SEM of Th17 cells (closed bars) and CD39+ Tregs (open bars) detected in naïve CD4+ T cells from 5 independent experiments. The purified naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 MAbs in the presence of the indicated cytokines, either alone or in various combinations for 7 days. *, P < 0.01 compared with their corresponding controls with no cytokines.

Inhibition of generation and differentiation of Th17 cells by CD39+ Tregs.

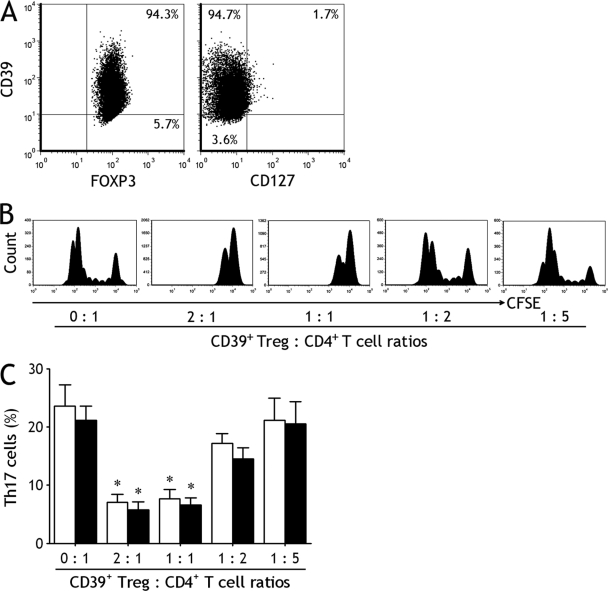

We purified CD39+ CD4+ CD25high T cells from both TPE and blood and found that majority of this Th subset were FOXP3 positive (92 to 97%) and CD127 negative (90 to 96%), possessing phenotypes typical of Tregs (Fig. 3 A).

Fig. 3.

CD39+ Tregs inhibit generation and differentiation of Th17 cells. (A) The representative dot plots showing the isolated pleural CD39+ CD4+ CD25high T cells were almost entirely CD39 positive and CD127 negative. (B) CFSE-labeled naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from tuberculous pleural effusion were cultured with indicated ratios of CD39+ Tregs and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 MAbs in the presence of IL-1β plus IL-6 for 7 days; CFSE+ cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry. The representative dot plots are from 1 of 5 independent experiments. (C) Naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from tuberculous pleural effusion (open bars) and blood (closed bars) were cultured in the above-described conditions, and Th17 cell numbers were determined by flow cytometry. The results are reported as mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 compared with naïve CD4+ T cells without CD39+ Tregs.

To assess the suppressor activity of these Tregs, we separated CD39+ Tregs and naïve CD4+ T cells from TPE and blood and then determined their proliferative capacity and the effect of CD39+ Tregs on CD4+ T cell proliferation. As shown in the representative suppression data (Fig. 3B), proliferative responses to anti-CD3 and -CD28 MAbs were observed in the purified naïve CD4+ T cell populations from TPE. When naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured with CD39+ Tregs, the proliferative response decreased as CD39+ Treg numbers increased.

As shown in Fig. 3C, generation and differentiation of Th17 cells were observed when the purified naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of IL-1β and IL-6. When CD39+ Tregs were added into the coculture, Th17 cell numbers decreased as CD39+ Treg numbers increased. There were no differences in inhibiting effects on Th17 cell numbers between pleural CD39+ Tregs and blood CD39+ Tregs.

LAP mediates Treg-induced inhibition of Th17 Cells.

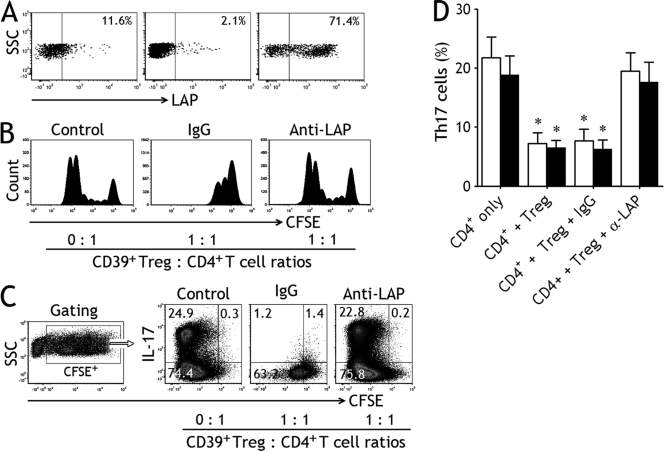

We determined LAP expression of on the cell surface of CD39+ Tregs by flow cytometry and found that LAP surface expressions on fleshly purified pleural CD39+ Tregs (median, 11.6%; 25th to 75th percentiles, 9.2% to 12.3%) were much higher than those in blood CD39+ Tregs (median, 2.1%; 0.8% to 4.1%) (P < 0.001); when CD39+ Tregs were cultured with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 MAbs in the presence of TGF-β for 7 days, the expression of LAP increased significantly (median, 71.4%; 59.0% to 74.5%) (Fig. 4 A).

Fig. 4.

Latency-associated peptide (LAP) mediates Treg-induced inhibition of Th17 cells. (A) Freshly purified CD39+ Tregs from tuberculous pleural effusion (left) and blood (middle) and cultured CD39+ Tregs (right) were analyzed by flow cytometry for determining the surface expression of LAP; data for 1 representative donor of 5 tested are shown. (B) CFSE-labeled naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from tuberculous pleural effusion were cultured alone serving as control (left) or with CD39+ Tregs (ratio, 1:1) and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 MAbs in the presence of IL-1β plus IL-6 for 7 days; isotype control IgG (middle) or an anti-LAP MAb (right) was added into the coculture, CFSE+ cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry. The representative dot plots are from 1 of 5 independent experiments. (C) CFSE-labeled naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from tuberculous pleural effusion were cultured in the above-described conditions, CFSE+ CD4+ T cells were gated to excluded CD39+ Tregs, and expression of IL-17 was examined by flow cytometry. The representative dot plots are from 1 of 5 independent experiments. (D) Naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from tuberculous pleural effusion (open bars) and blood (closed bars) were cultured alone or with CD39+ Tregs (ratio, 1:1), an anti-LAP MAb or isotype control IgG was added into the coculture, and Th17 cell numbers were determined by flow cytometry. The results are reported as mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.01 compared with CD4+ T cells alone.

The nature of LAP present on the surface of CD39+ Tregs that were responsible for their suppressive activity was also investigated in the present study. To do this, purified naïve CD4+ T cells served as a control, and CD39+ Tregs were cultured with CFSE-labeled naïve CD4+ T cells at a ratio of 1:1 in the presence of an isotype control or neutralizing anti-LAP MAbs. The representative suppression data for 1 from 5 TPE experiments are shown in Fig. 4B. CFSE+ CD4+ T cells alone proliferated extensively in size as reflected by increased forward scatter. The addition of isotype control MAb did not exert any effect on the inhibitory activity of CD39+ Tregs on the proliferative response of naïve CD4+ T cells. In contrast, the addition of anti-LAP MAb significantly reduced the inhibitory activity of CD39+ Tregs.

As shown in Fig. 4C, CFSE+ CD4+ T cells were gated to exclude CD39+ Tregs, and expression of IL-17 was examined. We noted that substantial amounts of Th17 cells could be generated and differentiated from naïve CD4+ T cells alone. Coculturing with CD39+ Tregs (ratio, 1:1) suppressed the frequency of Th17 cells, and the addition of anti-LAP MAb, but not a mouse IgG irrelevant isotype control, to the coculture markedly reversed the inhibitory effect exerted by CD39+ Tregs. The overall results in terms of mean ± SEM from 5 independent experiments are shown in Fig. 4D. Therefore, the above results indicate that CD39+ Tregs inhibit generation and differentiation of Th17 cells via a LAP-dependent mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Pleural effusion is characterized by the presence of specific subsets of leukocytes which, together with pleural mesothelial cells, contribute to the local production of cytokines and chemokines (1, 3). Lymphocytic pleural effusion refers to those types in which lymphocytes account for more than 50% of total leukocytes in the pleural effusion, which are commonly seen TPE (7). In previous studies, we and other authors have demonstrated that Treg numbers in TPE were much higher than those in blood (6, 21, 33). Although it cannot be excluded that the overrepresentation of Tregs in TPE may be due to increased local antigen stimulation, chemokine CCL22 might be capable of inducing the migration of Tregs to the pleural space of the patients with TPE (33). We once again observed in the present study that increased Treg numbers could be seen in TPE compared with blood. Moreover, we have demonstrated Th17 cells were significantly increased in TPE due to local generation and differentiation stimulated by IL-1β and/or IL-6.

It has been well known that various cytokines contribute to the generation and differentiation of Tregs or Th17 cells. Now that higher concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 and yet a lower concentration of TGF-β could be found in TPE (10, 12, 23, 30), these proinflammatory cytokines might affect the generation and differentiation of Tregs and/or Th17 cells in TPE. Indeed, we found in the present study that IL-1β or IL-6, but not TGF-β, could promote the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells, and the combination of IL-1β plus IL-6 significantly increased the percentage of Th17 cells at high extents compared with what was seen for any single one of them. On the other hand, TGF-β could reduce the increased Th17 cell numbers stimulated by IL-1β and/or IL-6. In contrast, TGF-β could promote the differentiation of CD39+ Tregs under the same conditions, whereas IL-1β and/or IL-6 did not affect the increase in Treg numbers induced by TGF-β.

Development of Th17 cells and Tregs is closely linked, and human Tregs can differentiate into Th17 cells (2, 4, 28, 29). The development and differentiation of Th17 cells was described to be linked to those of Tregs in a reciprocal fashion: both TGF-β and IL-6 were involved in this differentiation process (5, 27). Murine-activated Tregs promoted Th17 cell differentiation from CD4+ T cells via a TGF-β-dependent mechanism (27). However, the process of human Tregs differentiating into Th17 cells was enhanced by exogenous cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 and was inhibited by TGF-β (4, 28). The IL-17-producing Tregs strongly inhibit the proliferation of CD4+ responder T cells and maintain their suppressive function via a cell-cell contact mechanism (2, 29). In the present study, we noted fewer Th17 cells than Tregs in TPE, although the numbers of Th17 cells and Tregs were both increased in TPE compared with peripheral blood. Interestingly, we further noted that the numbers of Tregs and Th17 cells are inversely correlated in TPE but not in blood, suggesting that there could be a dynamic interaction between Th17 cells and Tregs in TPE. It was not surprising that immune response against M. tuberculosis was more intensive in a pathological site than in peripheral blood. We therefore were prompted to investigate whether Tregs are capable of suppressing the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells in the pleural space of patients with TPE.

Tregs in human studies have been being identified mostly based on high expression of CD25 and FOXP3 and, in some cases, low expression of CD127 (17). However, FOXP3 mRNA expression could be induced in human CD25− and CD8+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which were both negative for FOXP3 mRNA expression after isolation, indicating that FOXP3 expression in humans, unlike that in mice, may not be specific for Tregs and may be only a consequence of activation status (20). Furthermore, these markers cannot be used to identify Treg poststimulation in vitro, since their expression patterns change toward the Treg phenotype upon the activation of effector T cells. Recently, the technique of isolating human Tregs based on the CD39 expression has been proven to be highly desirable (19). In the present study, we isolated Tregs from TPE- and blood-based CD39 expression and found that CD39+ Tregs could be able to inhibit the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells from naïve CD4+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner.

The mechanism by which human Tregs inhibit the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells is unknown. Fletcher et al. (8) demonstrated for the first time that human Tregs can suppress IL-17 production by responder T cells; their data suggested that the CD39 molecule might be involved in the mechanism by which Tregs suppress the generation and differentiation of Th17, since the hydrolysis of ATP by CD39 could reduce IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells, and an analog of adenosine, the final breakdown product of ATP, effectively inhibited IL-17. Our data showed that pleural CD39+ Tregs could be induced to express LAP on their surfaces; we thus explored whether LAP was involved in the observed suppressive effect by CD39+ Tregs on the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells. In the in vitro coculture of naïve CD4+ T cells and CD39+ Tregs, we added a blocking MAb against LAP and observed that this MAb was able to reverse the inhibitory effect exerted by CD39+ Tregs. Thus, we herein provided evidence for the first time that pleural CD39+ Tregs inhibit the generation and differentiation of Th17 cells via a LAP-dependent mechanism.

Both Tregs and Th17 cells have been known to be involved in tuberculosis immunity (11, 22). Tregs recognizing M. tuberculosis-derived antigens specifically and potently restrict protective immune responses during tuberculosis (24, 25). It has been reported that IL-17 is an important cytokine in protective immunity against M. tuberculosis infection (26). We hypothesize that Tregs might participate in the suppression of local immune responses in by inhibiting Th17 responses in TPE.

This study supports earlier data that both Th17 cells and Tregs are present at high frequencies in TPE compared with the autologue blood. For the first time, we show that Th17/Treg imbalance exists in TPE and that CD39+ Tregs inhibit the generation and differentiation of pleural Th17 cells via a LAP-dependent mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (no. 30925032) and by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 30872343).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Antony V. B. 2003. Immunological mechanisms in pleural disease. Eur. Respir. J. 21:539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ayyoub M., et al. 2009. Human memory FOXP3+ Tregs secrete IL-17 ex vivo and constitutively express the T(H)17 lineage-specific transcription factor RORgamma t. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8635–8640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Babu S., Bhat S. Q., Kumar N. P., Kumaraswami V., Nutman T. B. 2010. Regulatory T cells modulate Th17 responses in patients with positive tuberculin skin test results. J. Infect. Dis. 201:20–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beriou G., et al. 2009. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood 113:4240–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bettelli E., et al. 2006. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature 441:235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen X., et al. 2007. CD4(+)CD25(+)FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells suppress Mycobacterium tuberculosis immunity in patients with active disease. Clin. Immunol. 123:50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalbeth N., Lee Y. C. 2005. Lymphocytes in pleural disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 11:334–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fletcher J. M., et al. 2009. CD39+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells suppress pathogenic Th17 cells and are impaired in multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 183:7602–7610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gleizes P. E., et al. 1997. TGF-beta latency: biological significance and mechanisms of activation. Stem Cells 15:190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoheisel G., et al. 1998. Compartmentalization of pro-inflammatory cytokines in tuberculous pleurisy. Respir. Med. 92:14–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hougardy J. M., et al. 2007. Regulatory T cells depress immune responses to protective antigens in active tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176:409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hua C. C., Chang L. C., Chen Y. C., Chang S. C. 1999. Proinflammatory cytokines and fibrinolytic enzymes in tuberculous and malignant pleural effusions. Chest 116:1292–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang L. Y., et al. 2008. Expression of soluble triggering receptor expression on myeloid cells-1 in pleural effusion. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 121:1656–1661 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawrence D. A. 2001. Latent-TGF-beta: an overview. Mol. Cell Biochem. 219:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Light R. W. 2002. Clinical practice. Pleural effusion. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1971–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu G. N., et al. 2009. Epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide-78 recruits neutrophils into pleural effusion. Eur. Respir. J. 34:184–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu W., et al. 2006. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J. Exp. Med. 203:1701–1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lucivero G., Pierucci G., Bonomo L. 1988. Lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood and pleural fluid. Eur. Respir. J. 1:337–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mandapathil M., Lang S., Gorelik E., Whiteside T. L. 2009. Isolation of functional human regulatory T cells (Treg) from the peripheral blood based on the CD39 expression. J. Immunol. Methods 346:55–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgan M. E., et al. 2005. Expression of FOXP3 mRNA is not confined to CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells in humans. Hum. Immunol. 66:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qin X. J., Shi H. Z., Liang Q. L., Huang L. Y., Yang H. B. 2008. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes in tuberculous pleural effusion. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 121:581–586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scriba T. J., et al. 2008. Distinct, specific IL-17- and IL-22-producing CD4+ T cell subsets contribute to the human anti-mycobacterial immune response. J. Immunol. 180:1962–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seiscento M., et al. 2010. Pleural fluid cytokines correlate with tissue inflammatory expression in tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:1153–1158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shafiani S., Tucker-Heard G., Kariyone A., Takatsu K., Urdahl K. B. 2010. Pathogen-specific regulatory T cells delay the arrival of effector T cells in the lung during early tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 207:1409–1420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sharma P. K., et al. 2009. FoxP3+ regulatory T cells suppress effector T-cell function at pathologic site in miliary tuberculosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179:1061–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Umemura M., et al. 2007. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J. Immunol. 178:3786–3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veldhoen M., Hocking R. J., Atkins C. J., Locksley R. M., Stockinger B. 2006. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity 24:179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Volpe E., et al. 2008. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat. Immunol. 9:650–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Voo K. S., et al. 2009. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:4793–4798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang T., et al. 2011. Increased frequencies of T helper type 17 cells in tuberculous pleural effusion. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 91:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winslow G. M., Cooper A., Reiley W., Chatterjee M., Woodland D. L. 2008. Early T-cell responses in tuberculosis immunity. Immunol. Rev. 225:284–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization 2010. 2009 update: tuberculosis facts. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2009/factsheet_tb_2009update_dec09.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu C., Zhou Q., Qin X. J., Qin S. M., Shi H. Z. 2010. CCL22 is involved in the recruitment of CD4+CD25 high T cells into tuberculous pleural effusions. Respirology 15:522–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]