Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against Haemophilus parasuis were generated by fusing spleen cells from BALB/c mice immunized with whole bacterial cells with SP2/0 murine myeloma cells. Desirable hybridomas were screened by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Neutralizing MAb 1D8 was selected in protection assays. ELISA results demonstrated that 1D8 can react with all 15 serotypes of H. parasuis and field isolate H. parasuis HLJ-018. Passive immunization studies showed that mice inoculated intraperitoneally with 1D8 had significantly reduced prevalence of H. parasuis colonization in the blood, lung, spleen, and liver and had prolonged survival time compared to that of the control group. Furthermore, the passive transfer experiment indicated that MAb 1D8 can protect mice from both homologous and heterologous challenges with H. parasuis. Using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE), the immunoreactive protein target for MAb 1D8 was identified. The data presented confirm the protective role of MAb 1D8 and identify OmpA as the target of the protective monoclonal antibody. The data suggest that OmpA is a promising candidate for a subunit vaccine against H. parasuis.

INTRODUCTION

Haemophilus parasuis is a Gram-negative, nonhemolytic, NAD-dependent bacterium belonging to the Pasteurellaceae family. The organism is an important upper-respiratory-tract pathogen in swine and is the etiological agent of Glässer's disease, which is characterized by fibrinous polyserositis, polyarthritis, meningitis, arthritis syndrome (22, 34), acute pneumonia without polyserositis, and acute septicemia (20). In recent years, with changes in production, such as early weaning and the use of three-site production systems, H. parasuis infection has been increasingly implicated as a major cause of nursery mortality in commercial swine herds, especially in specific-pathogen-free herds (24).

Although Glässer's disease can be successfully treated with antimicrobials (21), resistance to antimicrobials has been reported (1, 8, 35). Vaccination is an efficient way to control this disease provided the challenge is a homologous serotype (9), but major variability has been reported in cross-protection tests (9, 29). Therefore, the development of novel therapeutic methods is necessary. Miniats et al. (19) reported that the antibodies detected in the sera of vaccinated swine were directed only against H. parasuis outer membrane proteins (OMPs), which suggests that OMPs are more immunogenic than other components of H. parasuis. In recent years, the development of protein-based vaccines has been given much more attention, and several immunogenic OMPs of Gram-negative bacteria have been identified by immunoproteomic analysis and protection assays (9, 31, 33). The identification of novel and more efficient immunoprotective antigens is crucial for the development of a monovalent or multivalent subunit vaccine that can protect swine from H. parasuis infection.

OmpA, a major outer membrane protein of Gram-negative bacteria, is very highly conserved (7) and participates in biofilm formation, bacterial conjugation, bacteriophage binding, cell growth, and the invasion of mammalian cells (13). Several OmpA-like proteins have been identified in other Gram-negative bacteria, including Riemerella anatipestifer, Pasteurella multocida, and Leptospirosis (6, 12, 32). However, information regarding the H. parasuis OmpA-induced immune response is limited.

In our study, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against OmpA were generated and identified, and the neutralizing activities of MAbs were evaluated using in vitro and in vivo experiments. The results demonstrate the protective roles of MAbs raised against OmpA and indicate that OmpA is a promising candidate for a subunit vaccine against H. parasuis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture media.

The H. parasuis HLJ-018 strain was used for monoclonal antibody production. It was isolated from the nasopharyngeal swabs of a diseased piglet in Heilongjiang province, China, in 2009. Reference strains of H. parasuis (strains 1 to 15) were kindly supplied by X. Chen from Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Science, Beijing, China. H. parasuis was maintained on tryptic soy agar (TSA; BD) containing 10% bovine serum and 0.01% NAD or cultured aerobically in tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium (BD) plus 10% bovine serum and 0.01% NAD at 37°C.

Preparation of OMPs.

OMPs were prepared as previously described, with modifications (4, 34). Briefly, field isolate HLJ-018 of H. parasuis was grown in TSA at 37°C for 14 h with shaking. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were washed three times with precooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The harvested cells were resuspended in precooled Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2) containing protease inhibitor and then disrupted twice using a French pressure cell (Thermo) at 16,000 lb/in2. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation (8,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatants were diluted 10-fold with ice-cold 0.1 M NaCO3 (pH 11) and stirred slowly on ice for 1 h. The OMPs were collected by ultracentrifugation in a Beckman Optima Max ultracentrifuge (Beckman) at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, and then the supernatants were removed. The pellets were resuspended and washed in 50 mM Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0) and collected by centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellets were solubilized in lysis buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 1% [wt/vol] ASB-14, 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 40 mM Tris, and 2 mM tributylphosphine). Protein concentration was determined using a PlusOne 2-D Quant kit (GE Healthcare).

MAb production.

MAbs were produced as previously described, with slight modifications (16). Briefly, five 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized subcutaneously with 80 mg of H. parasuis mixed with Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma) on day 0 and then intraperitoneally on days 14 and 21. Blood was taken from each mouse, and antibody titers were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The mouse with the highest antibody titer in its serum was given a booster injection of 50 mg of H. parasuis intravenously 3 days prior to fusion. Sera collected from the nonimmunized and immunized mice served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

SP2/0-Ag 14 murine myeloma cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (PAA, Austria), 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco). Spleen cells from the immunized mouse were fused with SP2/0-Ag 14 myeloma cells using 50% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol (molecular weight, 2,000; Sigma). The fused cells were cultured in 96-well tissue culture plates (Costar) in the presence of hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and thymidine (Sigma), and the plates were incubated at 37°C in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2. Hybridoma culture supernatants were examined for the presence of antibodies by ELISA. Hybridoma cells producing the desired antibodies were cloned three times by limiting dilution.

Characterization of monoclonal antibodies. (i) ELISA.

Hybridoma culture supernatants were screened for antibodies by ELISA using OMPs, all 15 reference strains of H. parasuis, and field isolate H. parasuis HLJ-018. Polyclonal antibodies (PAbs) and SP2/0 culture supernatant were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

(ii) Identification of antibody isotypes.

MAb isotypes were determined using a mouse monoclonal subisotyping kit that contains rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin kappa (κ) and lambda (λ) light chains and IgM, IgA, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3. The procedure was performed by following the manual provided by the manufacturer (Southern Biotech).

Production and purification of ascites.

Hybridoma cells were harvested and washed twice in PBS (pH 7.2). Ten to 14 days after pristane injection, 8-week-old BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 106 hybridoma cells suspended in 0.5 ml normal saline. Fluid was collected from the peritoneal cavity 6 to 9 days after the injection of the cells. Ascites fluid was kept at 4°C for 1 h and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min. Supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until used. The purification of monoclonal antibodies was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (GE Healthcare, Sweden).

Polyclonal antibody production.

Polyclonal antibodies against H. parasuis were prepared by following a method described by Kelly et al. and Kim et al., with slight modifications (14, 15). Briefly, 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were prepared for polyclonal antibody production. H. parasuis antigen was mixed with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant (Sigma) and was injected intradermally into female BALB/c mice. Booster containing 100 mg of antigen mixed with Freund's incomplete adjuvant (Sigma) was injected twice at 1-week intervals. The 50 mg of H. parasuis antigen was injected intraperitoneally into mice 1 week after the final booster. After 3 to 5 days, antisera were collected from blood and clarified by overnight incubation at 4°C and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C.

Evaluation of the protective activities of antibodies using in vitro and in vivo experiments. (i) In vitro bactericidal assay.

The bactericidal assay was modified from previously published protocols (10, 28). Briefly, H. parasuis was grown to logarithmic phase and then was diluted to approximately 103 CFU/ml and mixed with 100 μl heat-inactivated MAb 1D8. The mixtures then were incubated in triplicate in sterile tissue culture microtiter plates (Costar) for 30 min at 37°C. The complement was guinea pig serum with undetected antibodies against H. parasuis. Fifty microliters of fresh guinea pig serum was added to each well and incubated at 37°C with gentle rocking for a further 120 min. Heat-inactivated mouse polyclonal antibodies against H. parasuis were used as positive controls. The irrelevant MAb 1G7 (against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus [PRRSV]) and PBS were used as negative controls. At the end of the experiment, samples were removed from each well and plated onto TSA agar plates, and colony numbers were measured after growth overnight at 37°C.

(ii) In vivo protection and bacterial elimination assays.

To determine the protective activity of MAb 1D8, protection and bacterial elimination assays were performed in vivo.

For the protection experiment, H. parasuis cultures were harvested after a 14-h overnight culture and washed three times with PBS. Groups of 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were immunized passively by the intraperitoneal injection of MAb 1D8, PAbs, and PBS at 1 h prior to challenged with a lethal dose of H. parasuis (approximately 3.0 × 109 CFU). Mouse polyclonal antibodies against H. parasuis were used as a positive control, and PBS was a negative control. The survival rates and times were recorded.

For the bacterial elimination assay, 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were divided into 10 groups, and a washed overnight culture of H. parasuis was adjusted to a concentration of 108 CFU/ml. The experiment was completed as described for the protection assay. To determine the cross-protective ability of MAb 1D8, mice from groups 1 to 4 were challenged with H. parasuis HLJ-018. Mice from groups 5 to 7 were treated with reference strain SW124, and mice in groups 8, 9, and 10 were inoculated with reference strain HS80.

During bacterial elimination assays, blood was obtained in triplicate from the tail veins of infected mice. The blood was serially diluted 10-fold and plated onto TSA to determine the colony numbers of H. parasuis at various time points. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by methoxyflurane overdose. Their lungs, spleens, and livers were removed aseptically and homogenized in PBS to make a 10% (wt/vol) suspension. The lung suspensions were serially diluted 10-fold, and 100 μl of each tissue homogenate was plated on TSA in triplicate to determine the number of CFU per gram of lung. The homogenate of liver and spleen also were plated on TSA agar to determine the prevalence of H. parasuis.

2-DE and immunoblotting analyses.

Two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) was performed using the IPGphor system (GE Healthcare) according to the method described by Wen et al. (30) with minor modifications. For the first-dimension electrophoresis, the OMP samples were diluted with rehydration buffer {7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% [wt/vol] 3-[(3-chcholamidopropyl)- dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) [CHAPS], 1% [wt/vol] ASB-14, 1% [wt/vol] dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5% [vol/vol] IPG buffer, 0.002% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue}. The immobilized strip gels (pH 3 to 10; 13 cm; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used for isoelectric focusing (IEF). After rehydration, IEFs were performed using the following step gradient: 30 V for 12 h, 200 V for 0.5 h, 500 V for 1 h, 1,000 V for 2 h, and 5,000 V until a total of 50 kVh had been achieved. IPG strips (GE Healthcare) were equilibrated with a solution containing 6 M urea, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 30% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.002% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, and 10 mg/ml DTT for 15 min and then treated with the same equilibration buffer containing 40 mg/ml instead of 10 mg/ml DTT for another 15 min. In the second-dimension electrophoresis, SDS-PAGE was performed at 4 W per gel for 45 min and then 15 W per gel until the bromophenol blue reached the bottoms of the gels. The proteins on the gels were visualized by silver staining. Silver-stained gel evaluation and data analysis were carried out using the ImageMaster 2D platinum version 6.0 program (GE Healthcare).

For the immunoblot assay, proteins on the gel were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Hybond-P; 0.45 mm; Amersham Biosciences). The membranes then were blocked in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 containing 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at room temperature and were probed with monoclonal antibody 1D8 against H. parasuis. After 3 to 10 min of washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000) for 1 h and visualized with DAB detection reagent (Tiagen, China). Controls were run concurrently on the membrane. All experiments were repeated five times.

Protein digestion and mass spectrometric analysis.

Protein spots were excised from the gel and digested as previously described (34). In brief, excised gels were destained in 30 mM potassium ferricyanide and 50 μl of 100 mM sodium thiosulfate, dehydrated with acetonitrile (ACN), and finally dried in a vacuum centrifuge for 30 min. The gels were reswollen with 5 μl of 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate containing 10 ng of trypsin at 4°C for 30 min and then digested overnight at 37°C. After tryptic digestion, peptides were extracted three times with 50% ACN containing 5% formic acid. The extracted solutions were pooled and lyophilized. The dried peptide was dissolved in 2 μl 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and used for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) analysis. Mass spectra were completed using an Ettan MALDI-TOF Pro mass spectrometer (GE Healthcare).

Database search and protein identification.

A search against the NCBI database (8,483,808 sequences; 2,914,572,939 residues) was performed using the Mascot database search engine (version 2.1; Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom). A MASCOT score greater than 82 was considered significant (P < 0.05). In addition, a hit was considered positive when at least two peptides were identified by MS/MS.

Statistical analysis.

The analysis of variance was applied to determine significant differences in numbers of H. parasuis in lungs among the groups of mice. The chi-square test was used to determine significant difference in survival time and prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs among the groups of mice. A Student's t test was applied to determine significant differences in the numbers of H. parasuis in lungs of mice.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of a murine monoclonal antibody against H. parasuis.

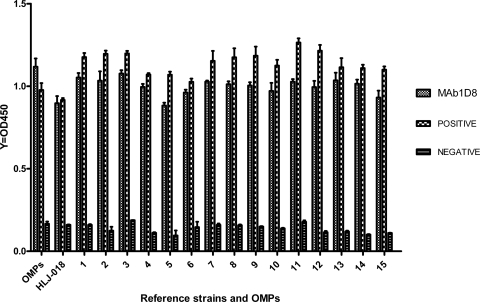

The hybridoma 1D8, generated by the fusion of murine myeloma SP2/0 cells with splenocytes from mice immunized with H. parasuis, secreted an IgG2b MAb with a κ light chain. By ELISA, MAb 1D8 showed a strong positive reaction to OMPs, all 15 reference strains, and the field isolate HLJ-018 of H. parasuis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ELISA reactivity of MAb 1D8 with OMPs, all 15 reference strains, and field isolate HLJ-018 of H. parasuis.

In vitro and in vivo protective efficiency and cross-reactivity of monoclonal antibodies against H. parasuis.

To determine the in vitro bactericidal activity of MAb 1D8 against H. parasuis, a complement-mediated killing assay was performed. The bactericidal activity of MAb 1D8 was assessed by the differences of colony numbers between experimental and control groups (Table 1). The colony numbers of H. parasuis were reduced significantly (P < 0.01) from 181 (group 3) and 141 (group 4) to 51 (group 1), a 72 and 64% reduction, respectively. As a positive control, the colony numbers of group 2 also were reduced significantly (P < 0.01) compared to those of group 3 and group 4, a 83 and 78% reduction, respectively. The results suggested that MAb 1D8 can activate guinea pig complement and effectively restrain the growth of H. parasuis.

Table 1.

Complement-mediated bactericidal activity of MAb1D8 in vitro

| Group | Treatmenta | No. of bacteria (means ± SEM) | Pc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1D8 + HPS + Cb | 51.33 ± 6.489 | <0.01 |

| 2 | PAb + HPS + C | 31.33 ± 4.055 | <0.01 |

| 3 | 1G7 (PRRSV) + HPS + C | 180.7 ± 19.55 | |

| 4 | PBS + HPS + C | 141.7 ± 10.37 |

H. parasuis (HPS) mixed with MAb 1D8, PAb, and MAb 1G7 (directed against PRRSV) and PBS 0.5 h prior to the addition of guinea pig complement. MAb 1D8, PAb, and MAb 1G7 were inactivated at 56°C for 30 min.

C, guinea pig complement.

The colony numbers of H. parasuis of groups 1 and 2 are significantly less (P < 0.01) than those of groups 3 and 4.

For the protection experiment, BALB/c mice were challenged with a lethal dose of H. parasuis 1 h after MAb 1D8 injection. All mice in the groups injected with MAb 1D8 and the control died, although the survival time of MAb-injected groups was longer than that of the control group. The survival times of mice were 31.6, 10.4, and 43.0 h, and the difference in survival time was significant (P < 0.01) between group 1 and group 2 (Table 2). These results demonstrate that MAb 1D8 is a protective MAb in mice.

Table 2.

Mortality and survival time of mice treated with MAb 1D8 and challenged with homologous H. parasuis HLJ-018a

| Group | Treatment | No. of mice | Mortality | Survival time (mean h ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1D8 | 6 | 6/6 | 31.60 ± 3.52b |

| 2 | PBS | 6 | 6/6 | 10.38 ± 2.28 |

| 3 | PAb | 6 | 6/6 | 43.00 ± 4.30b |

Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with MAb 1D8, PBS, and polyclonal antibodies at 1 h prior to challenge with 3.0 × 109 CFU of the homologous H. parasuis HLJ-018 strain. MAb 1D8 is directed against HLJ-018. PBS and polyclonal antibodies served as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Mean survival time was significantly longer than that for group 2.

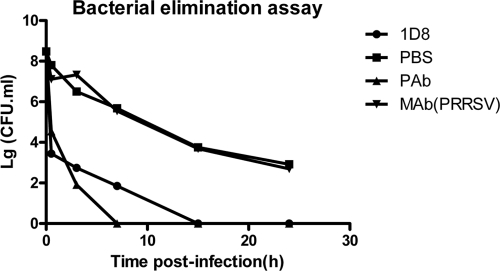

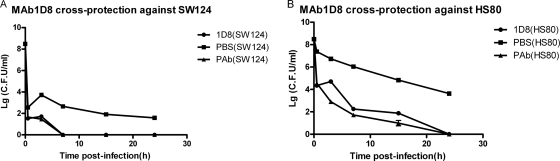

For the bacteria elimination assay, because MAb 1D8 can react with all reference strains by ELISA, we sought to determine whether MAb 1D8 could protect mice against heterologous challenges with serotype 4 and 5 strains, which are the most widespread strains of H. parasuis in China. The results showed that bacterial counts in the blood were significantly lower in mice receiving MAb 1D8 than in the control group. Moreover, bacteria were completely eliminated after 7, 15, and 24 h of infection of mice of MAb 1D8 groups challenged with SW124, HLJ-018, and HS80, respectively, whereas all of the control mice had positive blood cultures after 24 h (Fig. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Clearance of circulating H. parasuis HLJ-018 in blood of BALB/c mice injected with MAb1D8, PBS, PAb, and PRRSV MAb 1G7 at 0.5, 3, 7, 15, and 24 h postchallenge. MAb 1D8 was directed against H. parasuis HLJ-018. PBS and MAb 1G7 (directed against PRRSV) served as negative controls, and polyclonal antibodies served as positive controls. The colony number of H. parasuis in the blood of all the mice that were treated with MAb 1D8 decreased significantly compared to results for the negative control (t test; P < 0.01), and bacteria were completely eliminated after 15 h of infection.

Fig. 3.

Clearance of circulating H. parasuis SW124 (A) and HS80 (B) in blood of BALB/c mice injected with MAb1D8, PBS, and PAb at 0.5, 3, 7, 15, and 24 h postchallenge. PBS and polyclonal antibodies against H. parasuis served as negative and positive controls, respectively. The colony number of H. parasuis in the blood of all the mice that were treated with MAb 1D8 decreased significantly compared to those of negative controls (t test; P < 0.01), and bacteria were completely eliminated after 7 and 24 h of infection in mice challenged with SW124 and HS80, respectively.

Mice were sacrificed and H. parasuis was isolated from organs, including lungs, livers, and spleens. The prevalence and numbers of H. parasuis in lungs, livers, and spleens were compared between the groups. The prevalences of H. parasuis in lungs of mice which were challenged with the homologous H. parasuis HLJ-018 were 17.8% (1/6), 100% (6/6), 0 (0/6), and 100% (6/6) for groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and a significant (P < 0.01) difference among group 1, group 2, and group 4 was found. The number of H. parasuis cells in lungs was reduced by 6.7 × 102 (group 2) and 3.2 × 102 (group 4) to 7 (group 1), a 96- and 46-fold reduction (P < 0.01). The H. parasuis prevalences in nonrespiratory organs were 17.8% (2/12), 91.6% (11/12), 8.3%(1/12), and 75% (9/12) for groups 1 to 4, respectively. The H. parasuis prevalence had a significant reduction (P < 0.01) of 91.6, 75, and 17.8%. Significant protection was observed in mice immunized with MAb 1D8 and challenged with H. parasuis SW124 and HS80. The results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Prevalence and load of H. parasuis in lung and nonrespiratory organs of mice treated with MAb 1D8 and challenged with homologous H. parasuis HLJ-018d

| Group | Treatment | No. of mice | Prevalence (%) | Mean CFU/g ± SEMa | Load (CFU/g) | No. of nonrespiratory organs/total no. tested (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1D8 | 6 | 1/6 (17.8) | 0.400 ± 0.400b | 7 | 2/12c (17.8) |

| 2 | PBS | 6 | 6/6 (100) | 2.828 ± 0.125 | 6.7 × 102 | 11/12 (91.6) |

| 3 | PAb | 6 | 0/6 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1/12 (8.3) |

| 4 | 1G7 (against PRRSV) | 6 | 6/6 (100) | 2.505 ± 0.132 | 3.2 × 102 | 9/12 (75) |

Means of the log of geometric mean CFU per g of lung tissue. The geometric mean CFU per g of lung in each mouse was calculated and converted to the logarithmic number. The means and standard errors of the means then were calculated.

Mean CFU numbers in lung were significantly less (P < 0.01) than those for groups 2 and 4.

Prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs (liver and spleen) was significantly less (P < 0.01) than that for groups 2 and 4.

Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with MAb 1D8, PBS, polyclonal antibodies (PAb), and MAb 1G7 (directed against PRRSV) at 2 h prior to challenge with a nonlethal dose of H. parasuis HLJ-018 (approximately 108 CFU) and killed at 24 h postchallenge. The lung, liver, and spleen were collected, homogenized, and serially diluted in PBS, and the CFU per gram of lung tissue was determined by plating the tissue homogenate on TSA agar. The prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs was detected.

Table 4.

Prevalence and load of H. parasuis in lung and nonrespiratory organs of mice treated with MAb 1D8 and challenged with heterologous SW124 and HS80e

| Group | Treatment (strain) | No. of mice | Prevalence (%) | Load |

No. of nonrespiratory organs/total no. tested (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean CFU/g ± SEM | CFU/g | |||||

| 1 | 1D8 (SW124) | 6 | 0/6 (0) | 0a | 0 | 0/12c (0) |

| 2 | 1D8 (HS80) | 6 | 3/6 (50) | 1.933 ± 0.946b | 86 | 4/12d4 (33.3) |

| 3 | PBS (SW124) | 6 | 3/6 (50) | 1.723 ± 0.144 | 53 | 5/12 (41.7) |

| 4 | PBS (HS80) | 6 | 6/6 (100) | 3.705 ± 0.645 | 5.1 × 103 | 9/12 (75) |

| 5 | PAb (SW124) | 6 | 0/6 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0/12 (0) |

| 6 | PAb (HS80) | 6 | 2/6 (33.3) | 1.013 ± 0.541 | 13 | 3/12 (25) |

Mean CFU numbers in lung tissue were significantly less (P < 0.01) than those for group 3.

Mean CFU numbers in lung tissue were significantly less (P < 0.01) than those for group 4.

Prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs (liver and spleen) was significantly less (P < 0.01) than that for group 3.

Prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs (liver and spleen) was significantly less (P < 0.01) than that for group 4.

Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with MAb 1D8, PBS, and polyclonal antibodies (PAb) at 2 h prior to challenge with a nonlethal dose of H. parasuis SW124 and HS80 (approximately 108 CFU) and killed at 24 h postchallenge. The lung, liver, and spleen were collected, homogenized, and serially diluted in PBS, and the CFU/g of lung tissue were determined by plating the tissue homogenate on TSA agar. The prevalence of H. parasuis in nonrespiratory organs was detected.

These results suggest that MAb 1D8 has a potent bacteria-neutralizing activity in vitro and protective activity in vivo.

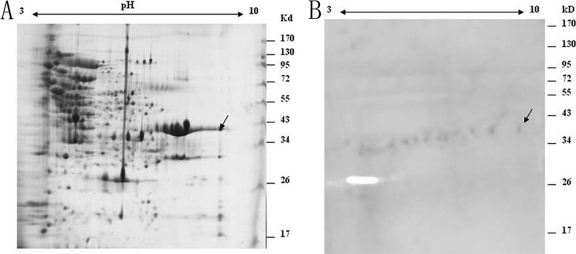

2-DE profile and immunoblot analysis of OMPs.

The OMPs of H. parasuis were separated by 2-DE. Many protein spots were detected using silver nitrate stain (Fig. 4A), and most of the OMP spots were distributed in the pH range of 4.0 to 9.0 with molecular masses ranging from 15 to 120 kDa. Four immunoreactive protein spots with molecular masses of approximately 35 kDa were detected with MAb 1D8 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). These proteins matched with the protein spots that could be seen in the preparative 2-DE gel.

Fig. 4.

2-DE proteome map (A) and immunoblot analysis (B) of outer membrane proteins (OMPs) from H. parasuis HLJ-018. OMPs were separated in the first dimension by isoelectric focusing (IEF) in the pI range of 3 to 10 and by 10% SDS-PAGE in the second dimension. Arrows indicate immunogenic proteins recognized with MAb 1D8.

Identification of immunogenic proteins.

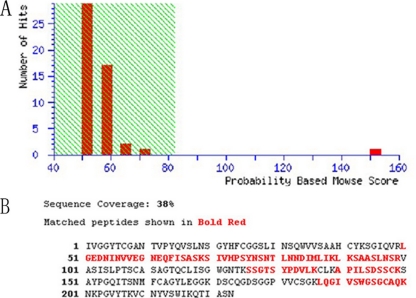

The immunoreactive protein spots were excised from the 2-DE gel by in-gel digestion and identified by MALDI-TOF-MS on the basis of peptide mass matching. By searching the NCBI database, the protein (protein scores 152 greater than 82 are significant, P < 0.05) that reacted with MAb 1D8 was identified as OmpA, a protein with a molecular mass of 37 kDa. Figure 5B shows the identified sequence with a coverage of 38%.

Fig. 5.

Identification of the immunogenic OmpA by MALDI-TOF-MS. (A) Identification results of protein spots. Protein scores (n=152 for MAb 1D8) that are greater than 82 are significant (P < 0.05). Protein scores are derived from ion scores as a nonprobabilistic basis for ranking protein hits. (B) The amino acid sequence of OmpA.

DISCUSSION

H. parasuis is a widespread major pathogen that affects naive herds and causes immense production losses, including nursery mortality, decreased weight gain, and lower meat value at slaughter (24). Although traditional vaccines are effective, they are not efficient for cross-protection. The identification of novel and conservative immunogenicity antigens is crucial for the development of an effective subunit vaccine. MAb 1D8 was generated in our study, and its protective role was investigated in mice. Additionally, the immunogenic protein target for MAb 1D8 was identified using 2-DE.

Several researchers have demonstrated that humoral immunity plays a major role in the protection of immunized mice against H. parasuis (11, 17, 19). MAbs, which are an important part of humoral immunity, were produced to study their roles in protection. Using in vitro and in vivo experiments, we evaluated the bactericidal activity and protective efficacy of these MAbs in terms of survival, H. parasuis load, and prevalence in organs in BALB/c mice. Our results clearly demonstrated that MAb 1D8 could facilitate bacterial clearance from the blood in a sublethal H. parasuis challenge, as revealed by reduced colony numbers and reduced prevalence of H. parasuis in various organs. In the in vitro assay, the results suggest that MAb 1D8 was involved in bactericidal activity against H. parasuis. Although all mice challenged with lethal H. parasuis died in both the experimental and control groups, the MAb clearly prolonged survival time in experimental mice compared to that of control mice. Tadjine et al. and Amano et al. (2, 18) reported that mortality in mice infected with excessive H. parasuis is mostly a result of endotoxemia, as the toxins released by the bacteria are strong enough to directly cause death in mice. Sakulramrung (27) reported that MAbs could exhibit neutralizing activities with decreased infectious doses; this also was observed in our bacteria elimination assay. Based on the findings mentioned above, it is speculated that an overwhelming infection containing high levels of toxins, rather than an insufficient neutralizing interaction between MAb 1D8 and H. parasuis, led to mouse death.

Using 2-DE, the immunogenic protein target for MAb 1D8 was identified as OmpA, which has a molecular mass of about 35 kDa, which is in accordance with the theoretical value. OmpA is a major outer membrane protein in Gram-negative bacteria and is conserved across different species. These characteristics indicate that OmpA plays an important functional role in Gram-negative bacteria. Many studies have demonstrated that OmpA is a crucial virulence-associated factor. Prasadarao et al. (26) reported that the capacity of an OmpA mutant to invade human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) was significantly reduced compared to that of the wild-type OmpA strain. OmpA causes Escherichia coli serum resistance by binding to the complement regulatory protein C4b-binding protein (25). Although OmpA is the most immunodominant antigen in the membrane, its role in immunoprotection is not clearly understood. Some studies show that antibodies against OmpA or OmpA-like proteins cannot confer passive immunoprotection (6, 10, 23). Huang et al. (12) deduced that neither recombinant OmpA nor cell-extracted protein elicits antibodies specific for the native proteins; additionally, they found that neither a single protein nor a subunit vaccination could afford effective protection and concluded that a combination of several kinds of proteins is necessary in a vaccine. However, a Crocquet-Valdes et al. (5) study demonstrated that immunization with a portion of rickettsial OmpA stimulates protective immunity against a lethal Rickettsia conorii challenge in mice. OprF, an OmpA homolog in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, also has been used for vaccine development, as it possesses protective epitopes (3). Although the immunoprotective role of OmpA is controversial, the OmpA-specific MAb 1D8 showed strong H. parasuis neutralizing capacity in our study. On the basis of our present knowledge of outer membrane proteins regarding adhesion to and invasion of host cells, we hypothesize that MAb 1D8 impairs the biological functions of OmpA by disrupting the interaction between H. parasuis and the host cell.

In summary, MAb 1D8, raised against OmpA, demonstrated neutralizing and protective activities in vitro and in vivo. This suggests that OmpA is a target for protective antibodies in mice. OmpA may be a desirable immunogen to stimulate immune protection; thus, it merits further study as a vaccine candidate against H. parasuis infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pat Blackall (Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries) and Xiaoling Chen (Institute of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Beijing Academy of Agiculture and Forestry Science) for the kind reference strain assistance.

This research was supported by grants from major international scientific cooperation projects in the national animal zoonoses prevention and control of key technologies (2010DFB33920).

We thank the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Science for supplying the required equipment and assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarestrup F. M., Seyfarth A. M., Angen O. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus parasuis and Histophilus somni from pigs and cattle in Denmark. Vet. Microbiol. 101: 143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amano H., Shibata M., Kajio N., Morozumi T. 1994. Pathologic observations of pigs intranasally inoculated with serovar 1, 4 and 5 of Haemophilus parasuis using immunoperoxidase method. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 56: 639–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumann U., Mansouri E., von Specht B. U. 2004. Recombinant OprF-OprI as a vaccine against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Vaccine 22: 840–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Connolly J. P., et al. 2006. Proteomic analysis of Brucella abortus cell envelope and identification of immunogenic candidate proteins for vaccine development. Proteomics 6: 3767–3780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crocquet-Valdes P. A., et al. 2001. Immunization with a portion of rickettsial outer membrane protein A stimulates protective immunity against spotted fever rickettsiosis. Vaccine 20: 979–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dabo S. M., Confer A., Montelongo M., York P., Wyckoff J. H., III 2008. Vaccination with Pasteurella multocida recombinant OmpA induces strong but non-protective and deleterious Th2-type immune response in mice. Vaccine 26: 4345–4351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies R. L., Lee I. 2004. Sequence diversity and molecular evolution of the heat-modifiable outer membrane protein gene (ompA) of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica, Mannheimia glucosida, and Pasteurella trehalosi. J. Bacteriol. 186: 5741–5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de la Fuente A. J., et al. 2007. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Haemophilus parasuis from pigs in the United Kingdom and Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 120: 184–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de la Fuente A. J., et al. 2009. Blood cellular immune response in pigs immunized and challenged with Haemophilus parasuis. Res. Vet. Sci. 86: 230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gatto N. T., Dabo S. M., Hancock R. E., Confer A. W. 2002. Characterization of, and immune responses of mice to, the purified OmpA-equivalent outer membrane protein of Pasteurella multocida serotype A:3 (Omp28). Vet. Microbiol. 87: 221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoffmann C. R., Bilkei G. 2002. The effect of a homologous bacterin given to sows prefarrowing on the development of Glasser's disease in postweaning pigs after i.v. challenge with Haemophilus parasuis serotype 5. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 109: 271–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang B., et al. 2002. Vaccination of ducks with recombinant outer membrane protein (OmpA) and a 41 kDa partial protein (P45N′) of Riemerella anatipestifer. Vet. Microbiol. 84: 219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jeannin P., et al. 2002. Outer membrane protein A (OmpA): a new pathogen-associated molecular pattern that interacts with antigen presenting cells-impact on vaccine strategies. Vaccine 20: A23–A27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelly N. M., Bell A., Hancock R. E. 1989. Surface characteristics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in a chamber implant model in mice and rats. Infect. Immun. 57: 344–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim Y. I., et al. 2007. Production and characterization of polyclonal antibody against recombinant ORF 049L of rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus) iridovirus. Proc. Biochem. 42: 134–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marandi M. V., Mittal K. R. 1995. Identification and characterization of outer membrane proteins of Pasteurella multocida serotype D by using monoclonal antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33: 952–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martín de la Fuente A. J., et al. 2009. Systemic antibody response in colostrum-deprived pigs experimentally infected with Haemophilus parasuis. Res. Vet. Sci. 86: 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martín de la Fuente A. J., et al. 2009. Effect of different vaccine formulations on the development of Glasser's disease induced in pigs by experimental Haemophilus parasuis infection. J. Comp. Pathol. 140: 169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miniats O. P., Smart N. L., Rosendal S. 1991. Cross protection among Haemophilus parasuis strains in immunized gnotobiotic pigs. Can. J. Vet. Res. 55: 37–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nedbalcova K., et al. 2011. Passive immunisation of post-weaned piglets using hyperimmune serum against experimental Haemophilus parasuis infection. Res. Vet. Sci. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicolet J. 1992. Haemophilus parasuis, p. 526–528 In Straw B. E., D'Allaire S., Mengeling W. L., Taylor D. J. (ed.), Diseases of swine, 7th ed Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nielsen R. 1993. Pathogenicity and immunity studies of Haemophilus parasuis serotypes. Acta Vet. Scand. 34: 193–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oldfield N. J., et al. 2008. Identification and characterization of novel antigenic vaccine candidates of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Vaccine 26: 1942–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oliveira S., Pijoan C. 2004. Haemophilus parasuis: new trends on diagnosis, epidemiology and control. Vet. Microbiol. 99: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Prasadarao N. V., Blom A. M., Villoutreix B. O., Linsangan L. C. 2002. A novel interaction of outer membrane protein A with C4b binding protein mediates serum resistance of Escherichia coli K1. J. Immunol. 169: 6352–6360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prasadarao N. V., et al. 1996. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli contributes to invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64: 146–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakulramrung R., Domingue G. J. 1985. Cross-reactive immunoprotective antibodies to Escherichia coli O111 rough mutant J5. J. Infect. Dis. 151: 995–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tadjine M., Mittal K. R., Bourdon S., Gottschalk M. 2004. Production and characterization of murine monoclonal antibodies against Haemophilus parasuis and study of their protective role in mice. Microbiology 150: 3935–3945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takahashi K., et al. 2001. A cross-protection experiment in pigs vaccinated with Haemophilus parasuis serovars 2 and 5 bacterins, and evaluation of a bivalent vaccine under laboratory and field conditions. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 63: 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wen L., Qian D., Yan X. 2011. Proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in hemolymph of Scylla serratia response to white spot syndrome virus infection. Aquaculture 314: 53–57 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu C., Wang S., Zhaoxia Z., Peng X. 2005. Immunogenic cross-reaction among outer membrane proteins of Gram-negative bacteria. Int. Immunopharmacol. 5: 1151–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yan W., et al. 2010. Identification and characterization of OmpA-like proteins as novel vaccine candidates for Leptospirosis. Vaccine 28: 2277–2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou M., et al. 2009. A comprehensive proteome map of the Haemophilus parasuis serovar 5. Proteomics 9: 2722–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou M., et al. 2009. Identification and characterization of novel immunogenic outer membrane proteins of Haemophilus parasuis serovar 5. Vaccine 27: 5271–5277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhou X., et al. 2010. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance among different serovars of Haemophilus parasui isolates Vet. Microbiol. 141: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]