Abstract

Epistatic interactions in which the phenotypic effect of an allele is conditional on its genetic background have been shown to play a central part in various evolutionary processes. In a previous study (J. B. Anderson et al., Curr. Biol. 20:1383-1388, 2010; J. R. Dettman, C. Sirjusingh, L. M. Kohn, and J. B. Anderson, Nature 447:585-588, 2007), beginning with a common ancestor, we identified three determinants of fitness as mutant alleles (each designated with the letter “e”) that arose in replicate Saccharomyces cerevisiae populations propagated in two different environments, a low-glucose and a high-salt environment. In a low-glucose environment, MDS3e and MKT1e interacted positively to confer a fitness advantage. Also, PMA1e from a high-salt environment interacted negatively with MKT1e in a low-glucose environment, an example of a Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibility that confers reproductive isolation. Here we showed that the negative interaction between PMA1e and MKT1e is mediated by alterations in intracellular pH, while the positive interaction between MDS3e and MKT1e is mediated by changes in gene expression affecting glucose transporter genes. We specifically addressed the evolutionary significance of the positive interaction by showing that the presence of the MDS3 mutation is a necessary condition for the spread and fixation of the new mutations at the identical site in MKT1. The expected mutations in MKT1 rose to high frequencies in two of three experimental populations carrying MDS3e but not in any of three populations carrying the ancestral allele. These data show how positive and negative epistasis can contribute to adaptation and reproductive isolation.

INTRODUCTION

Epistatic interactions in which the phenotypic effect of an allele is conditional on its genetic background (30) play a central role in a number of evolutionary processes, including adaptation (13, 33, 35), speciation (7, 18), and the evolution of sex (8). In only a few instances, however, have the underlying mechanisms of epistasis been documented. One such study described the mechanisms underlying epistatic interactions between a nuclear gene, APE2, in Saccharomyces bayanus and a mitochondrial gene, OLI1, in S. cerevisiae (18), while other studies have described the interactions between different mutations within single genes (21, 25). In this study, we investigated the cellular effects underlying a positive and a negative epistatic interaction among mutations in three genes, MKT1, MDS3, and PMA1, that arose in experimental populations of the yeast S. cerevisiae derived from a common ancestor and subjected to strong, directional selection in two environments: a high-salt and a low-glucose environment. Each of the mutant genes (designated with the letter “e”) confers a fitness advantage in a particular environment by altering the control of metabolic processes, either directly or indirectly. As described elsewhere (1), the negative epistasis between MKT1e and PMA1e was the first reported Dobzhansky-Muller (DM) incompatibility between experimentally evolved alleles of known genes and illustrates a plausible mechanism for the early onset of reproductive isolation with divergent adaptation.

In a previous study, experimental populations of the yeast S. cerevisiae originating from a single diploid progenitor were allowed to evolve for 500 generations in one of two divergent environments: a high-salt or a low-glucose environment (7). The genetic determinants of their adaptation were then identified through whole-genome resequencing of haploid representatives from three evolved populations, one from the low-glucose environment and two from the high-salt environment. The individual contribution of each evolved allele was determined by measuring the fitness of progeny segregating for the specific mutations (1). In one of the replicate populations that had evolved in a low-glucose environment, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the global regulators of gene expression MDS3 and MKT1 were recognized as the major fitness determinants before and after the diauxic shift from fermentation to respiration (6). MDS3 is a gene required for growth in alkaline media (3) and is a negative regulator of early meiotic gene expression (2), while MKT1 has been shown to regulate the translation of mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins. The Mkt1 protein mediates the interaction between Puf3, a sequence-specific RNA-binding protein targeting mRNAs involved in mitochondrial function, and P bodies, which control the degradation of certain mRNAs (19). The MDS3e allele conferred a fitness benefit before the diauxic shift and a fitness disadvantage after the shift. MKT1e had the opposite effect, conferring a fitness disadvantage at pre-diauxic-shift growth stages and an advantage after the shift. Yeast strains carrying both MDS3e and MKT1e had a fitness advantage during both the fermentative and respiratory growth stages relative to the progenitor strain in a low-glucose environment and exhibited synergistic epistasis. In isogenic backgrounds, the two mutations together resulted in a fitness contribution higher than the combined independent fitness contributions of the single mutations (1). Interestingly, the MKT1e allele (89G) evolved from the laboratory standard allele (89A) is identical to that fixed in wild populations of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus (20); this suggests its importance as a fitness determinant and a potential subject of natural selection. This MKT1e allele has been associated with increased expression of nuclear genes with mitochondrial functions (19), mitochondrial genome instability (9), and differences in a number of traits, including sensitivity to dipropyldopamine and phenylephrine (15) and resistance to 4-nitro-quinoline-1-oxide (4-NQO) (5). In addition to its synergistic epistasis with MDS3e, MKT1e was found to have an antagonistic epistatic interaction in a low-glucose environment with an allele of the PMA1 gene that arose in a high-salt environment. This negative interaction is an example of DM incompatibility (1). PMA1 encodes an essential plasma membrane H+-ATPase responsible for maintaining pH homeostasis and the transmembrane potential in yeast cells (11, 34).

In this study, our first objective was to document the cellular effects underlying the interactions between MKT1e and the evolved alleles of MDS3 and PMA1. An important feature of our study was that all of the phenotypic effects observed were attributable to naturally occurring variations at only three nucleotide positions, one in each of the genes of interest, with no additional, potentially confounding variation in the genome. There was no evidence for an epigenetic contribution to the phenotypes. The adaptive phenotypes were caused by the mutant alleles; in meiotic crosses, each phenotypic difference cosegregated precisely with a SNP (1). Since both the MKT1 and MDS3 genes are global regulators of gene expression, we first measured genome-wide expression for strains carrying one or both evolved alleles of these genes. Also, to better understand the phenotypic effects of the PMA1 mutation and to resolve its interaction with MKT1e, we measured several physiological parameters, such as intracellular pH (pHi) and proton efflux, for strains of different genotypes. A key objective was to test the evolutionary importance of the positive interaction between MKT1e and MDS3e; could we recapitulate the evolution of MKT1e in the background of MDS3e? In our previous study (1, 7), the mutation in MDS3 preceded the appearance of MKT1e in the experimental population. After quantifying the fitness advantage conferred by the MDS3e, MKT1e, and MKT1e genotypes over the progenitor strain in extended competition experiments, we tested whether this trajectory of experimental evolution was repeatable. We set the two experimental conditions: an ancestral background containing MDS3e and a growth cycle emphasizing respiration over fermentation, predicted to recapitulate the origin, spread, and fixation of the MKT1e mutation in large populations. This exact evolutionary change was observed in two of three populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome-wide expression measurements.

Haploid yeast strains described by Anderson et al. (1) carrying no evolved alleles (progenitor strain) or different combinations of the evolved alleles studied (PMA1e, MDS3e, and MKT1e) and devoid of all other evolved alleles were used in experiments. One strain representative of each of the following genotypes was studied: the ancestral (strain Sce13), MDS3e (Sce4631), MKT1e (Sce4668), MDS3e MKT1e (Sce4587), and PMA1e MKT1e (Sce4658) genotypes. Yeast cells were removed from the archive (2 replicates per strain) and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The optical densities of the cultures at 600 nm (OD600) were measured with a spectrophotometer, and each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 4.0. A 50-μl volume from each culture was used to inoculate 250 ml of defined low-glucose medium (LGM) (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.25% dextrose, 0.02 mg of uracil ml−1). The inoculated medium was incubated at 30°C with shaking (250 rpm), and the culture was allowed to grow until it reached an OD600 of approximately 0.2 (≈17 h). Two 20-ml aliquots from each LGM culture were added to tubes containing 30 ml of cold methanol (stored at −80°C), mixed, and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The cells were then washed with 20 ml of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water, centrifuged, and resuspended in 1 ml of RNAlater (Ambion, Foster City, CA). The two samples from each culture were pooled and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Samples were prepared using a GeneChip 3′ IVT Express kit and were hybridized to GeneChip Yeast Genome 2.0 arrays according to the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix). The arrays were scanned with a GeneChip scanner, model 3000. Background correction and normalization of signal intensities were carried out using Expression Console software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). All sample preparation, as well as the hybridization and scanning protocols, were performed by The Centre for Applied Genomics (TCAG), The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. Subsequent statistical analyses were conducted using the Partek Genomics Suite (Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO). Expression values for all genes were log2 transformed, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess differences in expression between strains carrying evolved alleles and the progenitor strain. The criteria for selecting differentially expressed genes were a false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected P value lower than 0.05 and a fold change greater than 1.5. ANOVA was also conducted to test for significant effects of the interaction between MKT1e and MDS3e on gene expression. Interaction factors with an FDR-corrected P value lower than 0.01 were accepted as significant (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). A Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (14) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp), and results with a false discovery rate of <10% are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material. A heat map (see Fig. 1) was generated using MeV software, version 4.6.1 (http://www.tm4.org/mev/). The expression values shown in Fig. 1 and 2 are the averaged values for each strain carrying evolved alleles normalized against the average expression values obtained for the progenitor strain (n = 2).

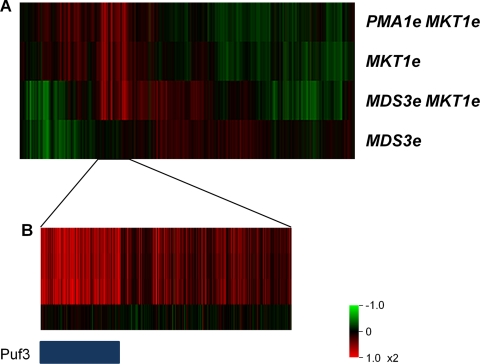

Fig. 1.

Genome-wide expression changes in strains carrying evolved alleles. (A) Genome-wide expression profiles of strains carrying the evolved alleles PMA1e MKT1e, MKT1e, MDS3e MKT1e, and MDS3e grown in a low-glucose environment. Red represents genes that are induced, and green represents those that are repressed, relative to the mean expression levels in the progenitor strain (no evolved alleles) under the same conditions. (B) Genes with high expression specific for MKT1e are enriched for Puf3 targets. The blue bar indicates genes in the Puf3 module. Genes are reordered by membership in the Puf3 module.

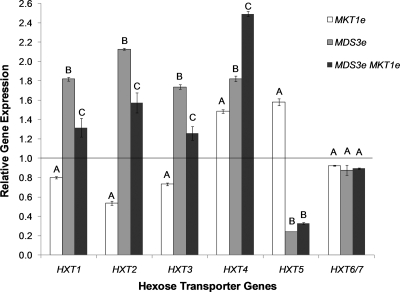

Fig. 2.

Relative expression levels of hexose transporter genes for strains carrying evolved alleles. Values represent the mean gene expression levels of strains carrying evolved alleles compared to the mean expression levels of the progenitor strain. Different capital letters above the bars indicate groups of strains with different expression levels for the individual genes (by the Tukey HSD test with 95% simultaneous confidence intervals). Error bars, ±1 standard error of the mean (n = 2).

Plating of strains on buffered medium.

Yeast cells were removed from the archive and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid YPD at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The cultures were then diluted (∼4 × 10−5 OD unit) and were plated onto buffered or unbuffered defined LGM agar plates (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.25% dextrose, 0.02 mg of uracil ml−1, 2% agar; 30 ml per 90-mm-diameter plate). The pH of the medium was set to 2.7 by the addition of 0.1 M phosphate citrate buffer. To avoid hydrolysis of the agar, the buffer was autoclaved separately and was allowed to cool before mixing. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 76 h, and the diameter of observed single colonies was measured using a light microscope fitted with an ocular micrometer. A total of 30 measurements per strain were obtained for each experiment. All experiments were performed in replicates of 3. The averaged measurements obtained for strains carrying evolved alleles in each experiment were divided by the average colony size obtained for the progenitor strain. Two-tailed t tests were performed to assess the significance of differences between measurements obtained on buffered versus unbuffered media for each strain.

Proton efflux measurements.

Yeast cells were removed from the archive and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid YPD at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures were measured with a spectrophotometer, and each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 4.0. A volume of 50 μl from each culture was used to inoculate 250 ml of defined LGM. The inoculated medium was incubated at 30°C with shaking (250 rpm), and the culture was allowed to grow until it reached an OD600 of approximately 0.2 (≈17 h). Portions (100 ml) from each culture were harvested and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm and 4°C for 10 min (these settings were used for all subsequent centrifugations). The cells were then washed with 100 ml of distilled water (dH2O) and were resuspended in 50 ml of dH2O. 2-Deoxyglucose (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, and the suspension was incubated at room temperature (RT) with shaking for 60 min. The cells were again washed with 50 ml of dH2O, resuspended in 50 ml of dH2O, and incubated at RT with shaking for 17 h. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in 97.5 ml of dH2O, and the pH of the suspension was monitored for 5 min before the addition of 2.5 ml of a 10% glucose solution. The pH of the suspension was then monitored for 45 min at 1-min intervals. All experiments were replicated three times. A standard pH electrode enclosed in dialysis tubing containing 10 ml of dH2O was used to monitor the pH of the cell suspension. The greatest pH decrease observed within a 5-min period was used to calculate the maximum rate of pH change in each experiment. All experiments were performed in replicates of 3. Two-tailed t tests with 95% confidence intervals were performed to assess the significance of the differences observed between strains carrying the evolved or the ancestral allele of PMA1.

Intracellular pH measurements.

5(6)-Carboxyfluorescein diacetate (CF-DA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (20 mM). Buffers used for dye loading and for calibration purposes were prepared as described by Weigert et al. (38). Yeast cells were removed from the archive and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid YPD at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures were measured with a spectrophotometer, and each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 4.0. A 10-μl volume from each culture was used to inoculate 50 ml of defined LGM. The inoculated medium was incubated at 30°C with shaking (250 rpm), and the cultures were allowed to grow for approximately 17 h. The OD600 of the cultures were measured, and a volume equal to 3.5 ml per OD600 unit from each culture was harvested and centrifuged at 4,200 rpm and 4°C for 2 min (these settings were used for all subsequent centrifugations). The cells were then washed 3 times with 1 ml of ice-cold loading buffer and were resuspended in 1.3 ml of the same buffer. Portions (130 μl) of the stock CF-DA solution were added to the cell suspension, which was then shaken vigorously for 5 min. Following the addition of the dye, samples were protected from light exposure. One hundred-microliter volumes of the cell-dye suspension were added to 12 tubes containing 900 μl of loading buffer at room temperature and were incubated at 30°C for 15 min. All samples were centrifuged and washed with 1 ml of cold loading buffer twice. One of the samples was resuspended in 1 ml of loading buffer and was kept on ice before analysis (live sample). The remaining 11 samples were used to generate a calibration series matched to each experiment (protocol modified from that of Valli et al. [36]). Cells were permeabilized by incubation with amphotericin B in citrate phosphate buffers with pH values ranging from 5.4 to 7.4 in 0.2 increments as follows. To each of the remaining 11 samples were added 20 μl of 0.5 M stock 2-deoxy-d-glucose solution (Sigma Chemicals), 960 μl of cold citrate phosphate buffer, and 20 μl of a freshly prepared 3 mM amphotericin B solution (Sigma Chemicals). The samples were then incubated at 37°C for 45 min with shaking. All samples were kept on ice and were diluted by a factor of 10 before flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometric analyses were performed with a Cell Lab Quanta system (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Samples were excited with a 488-nm argon ion laser, and the fluorescence emission was measured through 525-nm (±20 nm) and 575-nm (±15 nm) band-pass filters. A total of 20,000 cells were measured per sample, and all data were acquired on a logarithmic scale. As described by Weigert et al. (38), for each measurement, the pH-dependent fluorescence intensity measured at 525 nm was divided by the pH-independent intensity measured at 575 nm to correct for differences in dye uptake. For each experiment, the fluorescence ratios obtained for the samples incubated at different pHs were used to construct a calibration curve (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Changes in the fluorescence ratio were highly correlated with differences in the incubation pH (R2, >0.99), except for experiments with yeast strains carrying the MKT1e allele. The fluorescence ratio obtained for the live sample was then applied to the curve in order to estimate the intracellular pH of the strain. Experiments were performed in replicates of 2 for each strain. Two-tailed t tests with 95% confidence intervals were performed to assess the significance of differences observed between strains.

Budding index and cell size measurements.

Yeast cells were removed from the archive and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid YPD at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures were measured with a spectrophotometer, and each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 4.0. A 2-μl volume from each culture was used to inoculate 10 ml of defined LGM. The inoculated medium was incubated at 30°C with shaking (250 rpm) and was allowed to grow until it reached an OD600 of approximately 0.2 (≈17 h). A light microscope fitted with a digital camera was used to capture images of the different cultures. The images were analyzed using ImageJ, version 1.43, software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html). In each experiment, the diameters of 300 cells were measured, and 600 cells were assessed for the occurrence of budding. The average measurement obtained for strains carrying evolved alleles was divided by the average measurement obtained for the progenitor strain in each experiment in order to obtain relative cell size and budding index values. Experiments were performed in replicates of 3. A Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test with 95% simultaneous confidence intervals was performed to assess the significance of differences observed among strains.

Competitions in low-glucose medium.

For competitions in LGM, yeast strains with an MKT1e or MDS3e MKT1e genotype were set to compete against the progenitor strain. Yeast cells were removed from the archive and were grown overnight in 10 ml of liquid YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) at 30°C on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures were measured with a spectrophotometer, and each culture was diluted to an OD600 of 4.0. Cultures of competing strains were mixed at the appropriate ratio (ratio of the strain carrying evolved alleles to the progenitor strain, 1:100), and 100 μl of each competition mix was used to inoculate 9.9 ml of defined LGM (0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.25% dextrose, 0.02 mg of uracil ml−1). The cell mixtures were propagated in LGM (30°C, 250 rpm) with daily serial transfers by following two different protocols. Under the “long-transfer” regimen, the cultures were transferred with a 1:100 dilution factor and were allowed to grow for 24 h between transfers, nearly reaching saturation. Under these conditions, the strains were expected to go through the diauxic shift and to experience long periods of respiratory growth. In contrast, the “short-transfer” regimen was designed to constantly maintain the yeast populations in a fermentative or pre-diauxic-shift growth stage. Under this protocol, the transfers were done with a 1:1,000 dilution factor and before the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.5. Genomic DNA was extracted at all transfers under both protocols. A total of 13 transfers were conducted for each competition, corresponding to approximately 79 and 113 elapsed generations for yeast populations under the long-transfer and short-transfer regimens, respectively. All competition experiments were performed in replicates of 3.

Changes in allele frequency throughout the competition were assessed by means of quantitative Southern hybridization with allele-specific probes as described by Anderson et al. (1). A 318-bp DNA sequence spanning the MKT1 SNP region was PCR amplified for all DNA samples collected. The amplicons were then transferred to a nylon membrane and were hybridized sequentially with 15-base oligonucleotide probes 5′ end labeled with 32P. The two allele-specific probes had the SNP site in the center and were hybridized 2 to 4°C above the predicted melting temperature (Tm) to ensure specificity. The membranes were analyzed with a phosphorimager, and the intensity of the hybridization signal was corrected for background noise. The proportion of each competing strain was calculated by the equations V(A or E) = [S(A or E) − BG]/Meanblot [S(A or E) − BG] and PA = VA/(VA + VE) or PE = VE/(VA + VE), where V(A or E) represents the normalized signal from each sample in a blot with the hybridization of the ancestral (A) or evolved (E) probes; S(A or E) is the raw signal obtained from each sample; and BG is the average background noise in a blot for each hybridization. PA and PE represent the proportions of ancestral- and evolved-allele carrier strains present in each sample. The ratio between competing strains in a culture was always highly correlated with the hybridization signal of the allele-specific probes (R2, >0.99), as determined through a series of calibration standards. The selection coefficient (s) of the genotypes studied was calculated as {ln[x(t2)/y(t2)] − ln[x(t1)/y(t1)]}/Δt, where x is the proportion of the strain carrying evolved alleles, y is the proportion of the progenitor strain, and Δt is the difference in generations between t2 and t1. In the calculation of s for the MKT1e strain, t1 is zero and t2 is the number of generations that have elapsed at the competition endpoint under each regimen. The maximum frequency reached by the MKT1e strain and the number of generations needed for the MDS3e MKT1e strain to reach such a frequency under each regimen were designated x(t2) and t2, respectively, in estimating s for the MDS3e MKT1e strain.

Recapitulation of the appearance and spread of the MKT1 mutation.

Yeast cells from strains with a progenitor or an MDS3e genetic background were removed from the archive, streaked onto YPD agar plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 2% agar), and incubated at 30°C for 48 h. Single colonies were then isolated (3 replicates per strain) and were used to inoculate 25 ml of defined LGM. After a 24-h incubation period (30°C, 250 rpm), 22 ml from each culture was used to inoculate 238 ml of LGM. The cultures were then propagated in LGM with 24-h serial transfers for a period of 38 days. To minimize the chance of “discarding” mutations that had arisen during the serial transfers and to ensure a larger population size, the 6 initial transfers were done with a 1:10 dilution factor and a total volume of 250 ml. The 32 subsequent transfers were performed with a 1:100 dilution factor and a total volume of 10 ml. Genomic DNA was extracted, and the OD600 of each culture was measured at all transfers. A total of 38 transfers, corresponding to 227 elapsed generations for the propagated populations, were conducted. After completion of the transfers, the MDS3e and MKT1e SNP sites were sequenced in order to detect mutations and to confirm the genetic background of the yeast strains. DNA sequences of 318 and 386 bp, spanning the MKT1e and MDS3e SNPs, respectively, were sequenced for samples obtained at the first and last transfers (sequencing services were provided by TCAG, Toronto, Canada). Southern hybridizations were used to screen for the presence of mutations detected by sequencing as well to determine changes in allelic frequencies throughout the experiment. In this procedure, the same DNA sequences used for sequencing were PCR amplified for all DNA samples collected. As in the “low-glucose” competition protocol, the amplicons were transferred to a nylon membrane and were hybridized sequentially with 15-base oligonucleotide probes 5′ end labeled with 32P. Proportions of alleles present in a sample and selection coefficient (s) values of different genotypes were calculated as described above for the competitions in low-glucose medium. The selection coefficient formula given in the preceding section was applied to the linear range of the plots showing frequency changes for the evolved alleles (see Fig. 7 and 8).

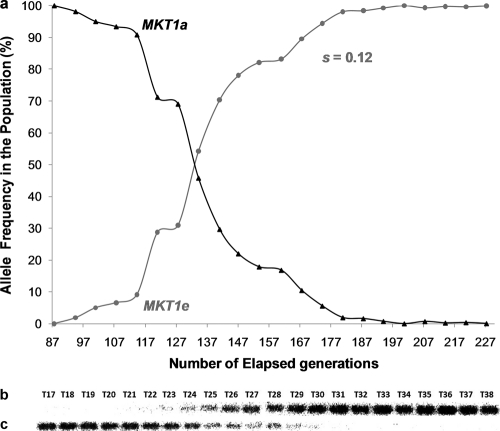

Fig. 7.

Changes in the frequencies of MKT1 alleles in yeast populations with an MDS3e genetic background in the first replicate experiment. The yeast populations were propagated in a low-glucose environment through serial transfers for 227 generations. (a) Changes in the frequencies of evolved (MKT1e) and ancestral (MKT1a) alleles of MKT1 throughout the experiment, as assessed by Southern blotting. Data points represent consecutive transfers. (b and c) Phosphor screen images of blots showing DNA samples from the respective transfers (T) after hybridization with the MKT1e (b) and MKT1a (c) probes.

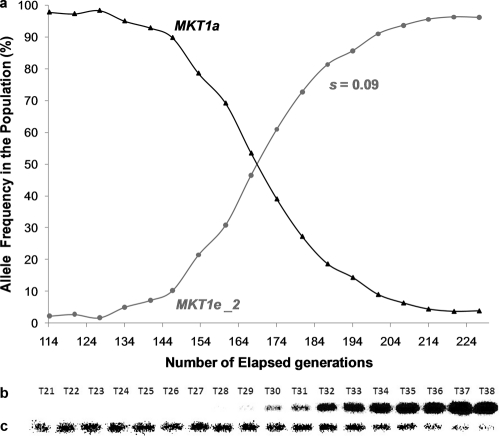

Fig. 8.

Changes in the frequencies of MKT1 alleles in yeast populations with an MDS3e genetic background in the second replicate experiment. The yeast populations were propagated in a low-glucose environment through serial transfers for 227 generations. (a) Changes in the frequencies of evolved (MKT1e-2) and ancestral (MKT1a) alleles of MKT1 throughout the experiment, as assessed by Southern blotting. Data points represent consecutive transfers. (b and c) Phosphor screen images of blots showing DNA samples from the respective transfers (T) after hybridization with the MKT1e-2 (b) and MKT1a (c) probes.

RESULTS

Genome-wide expression measurements.

To assess gene expression changes associated with the three mutations, we conducted genome-wide expression measurements for the strains carrying evolved alleles and for the progenitor strain. The evolved allele of MKT1 was associated with 1.5-fold or greater changes in the expression of 223 genes, especially those encoding mitochondrial proteins. The set of upregulated genes for the MKT1e strain was highly enriched for the Gene Ontology (GO) term “mitochondrion organization” (P = 4 × 10−50), containing 72 of 317 genes described (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Also, the cluster of upregulated genes specific for strains carrying MKT1e (Fig. 1B) was enriched for Puf3 targets containing 144 of the 210 target genes (12). A comparison of the expression profile obtained for the strain carrying MKT1e and the PMA1e MKT1e double mutant showed a significant difference in the expression level of only 1 gene out of 5,841 surveyed, suggesting a non-expression-based mode of interaction for the two evolved alleles. The single differentially expressed gene was Bat1, which showed 1.52-fold lower expression than that in the MKT1e strain. Bat1 encodes a mitochondrial aminotransferase enzyme, and its deletion has been shown not to impair cell growth (16). The expression of Bat1 itself is induced by cell growth, and its downregulation is likely a result of the decreased fitness of the PMA1e MKT1e strain (10).

The MDS3 evolved allele was associated with changes in the expression of 138 genes and with significant downregulation of genes involved in the response to temperature stimuli (P = 1.8 × 10−22). Notably, MDS3e was also associated with the upregulation of genes responsible for carbohydrate transport (P = 0.003), including four of the seven main glucose transporter genes, whose expression is regulated by glucose levels (Fig. 2) (31). The MKT1e allele was associated with significantly lower expression of these genes (HXT1, HXT2, HXT3, and HXT4) than those for both the MDS3e and MDSe MKT1e genotypes. These two alleles had a synergistic effect on the expression of HXT2 (P = 3.1 ×10−4) but appeared to have an additive effect on the expression of the other three genes, since the strain with an MDS3e MKT1e genotype presented expression levels intermediate between those of the strains carrying the single mutations. A different pattern was observed for the HXT5, HXT6, and HXT7 genes, whose expression is not as dependent on glucose concentrations (Fig. 2). The expression of HXT5 is induced by decreased growth rates (37). HXT6 and HXT7, which differ by only two amino acids, are expressed at higher basal levels than the other glucose transporters and are only modestly induced by glucose (27). Moreover, a comparison between the expression profiles of the MKT1e and MDS3e MKT1e strains shows that 163 genes have a 1.5-fold or greater difference in expression levels. The MDS3e and MKT1e alleles were found to have an epistatic effect on the expression of 250 genes (FDR-corrected P value, <0.01), including 50 mitochondrial genes. A synergistic effect on the expression of 30 mitochondrial genes was observed, while an antagonistic effect was observed for the remaining 20 genes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Overall, the interaction between these two alleles had a positive effect on the expression of mitochondrial genes. The set of upregulated genes for the MDS3e MKT1e strain was even more enriched for genes described under the GO term “mitochondrion organization” (P = 3.7 × 10−58) than that for the MKT1e strain, including 84 of 317 genes described.

Plating of strains on buffered medium.

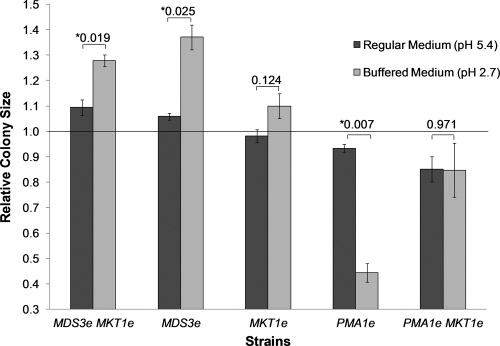

Yeast strains were plated on buffered medium (pH 2.7) in order to determine if the PMA1 mutation reduces the H+ efflux from cells, rendering strains carrying the evolved allele less resistant to low pHs. The PMA1e strain was observed to be the most sensitive to a low pH and was the only strain to display a significant decrease in colony size when growing on buffered medium (Fig. 3). In contrast, the PMA1e MKT1e double mutant strain showed no significant differences in colony size between the two media. This difference in results is likely due to the long incubation period (76 h) necessary to obtain colonies of measurable size on the low-glucose buffered medium. This prolonged incubation would have exposed the strains to long periods of respiratory growth, in which the evolved allele of MKT1 might confer an advantage.

Fig. 3.

Colony size measurements for strains plated on regular and buffered low-glucose medium (pH 2.7). Values represent mean colony sizes for strains carrying evolved alleles relative to the mean colony size calculated for the progenitor strain. The strains were plated on regular and buffered low-glucose agar media and were incubated for 76 h at 30°C. Error bars, ±1 standard error of the mean (n = 3). Numbers above bars are P values from two-tailed t tests assessing the significance of the differences between values obtained on regular and buffered media for each strain (*, significant difference [P, <0.05]).

Proton efflux and intracellular pH (pHi) measurements.

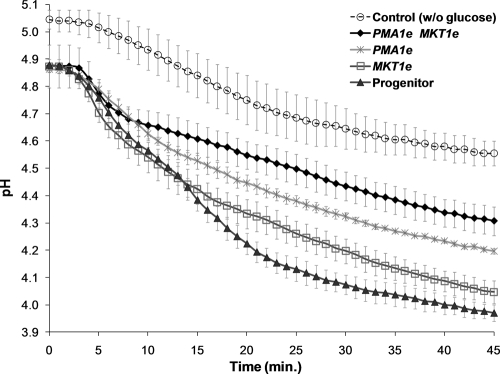

To directly assess the deficiency in proton efflux associated with the evolved allele of PMA1, we monitored changes in external pH following the addition of glucose to suspensions of starved cells of different genotypes (Fig. 4). The maximum rate of pH change observed for yeast cells carrying the evolved allele of PMA1 (0.038 ± 0.005 pH unit/min) was significantly lower (P = 0.025) than that measured for strains carrying the ancestral allele of PMA1 (0.050 ± 0.006 pH unit/min).

Fig. 4.

Proton efflux measurements. Changes in external pH following the addition of glucose to suspensions of starved cells of the indicated genotypes are plotted. Yeast cells were incubated with 2-deoxyglucose and were starved for 17 h. At time zero, glucose was added to the solution (0.25%), and the external pH was then monitored at 1-min intervals for 45 min. Values are mean pH measurements at each time point noted for the strains studied. The “control” series represents data obtained in experiments with the progenitor strain without the addition of glucose. The starting pH of the other series is lower than that of the “control” due to the addition of glucose, which is weakly acidic. Each experiment was performed in replicates of 3.

The plasma membrane H+-ATPase encoded by PMA1 is responsible for the maintenance of pHi in yeast cells. Therefore, our next step was to determine how the lower rate of proton efflux associated with PMA1e affected the intracellular pHs of the strains studied. For this purpose, cells of the different strains were stained with the pH-dependent fluorescent dye 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, and differences in fluorescence intensity were assessed using a flow cytometer. For each experiment, a matched calibration was performed with the same batch of cells (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), allowing for the determination of absolute pHi values. The progenitor strain exhibited an intracellular pH of 6.79 ± 0.02, while the PMA1e strain had a significantly lower pHi of 6.23 ± 0.03 (P = 0.033). The pHi value obtained for the progenitor strain is in agreement with measurements obtained for yeast populations during logarithmic growth (38). It was not possible to determine the intracellular pHs of strains carrying the evolved allele of MKT1, since there was no correlation between pH values and fluorescence intensities on the in situ calibrations performed for those strains (see Materials and Methods); the two most likely causes were that the evolved allele of MKT1 either affected dye localization within the cell or reduced the ability of amphotericin B to increase cell membrane permeability, but the actual reason is not known.

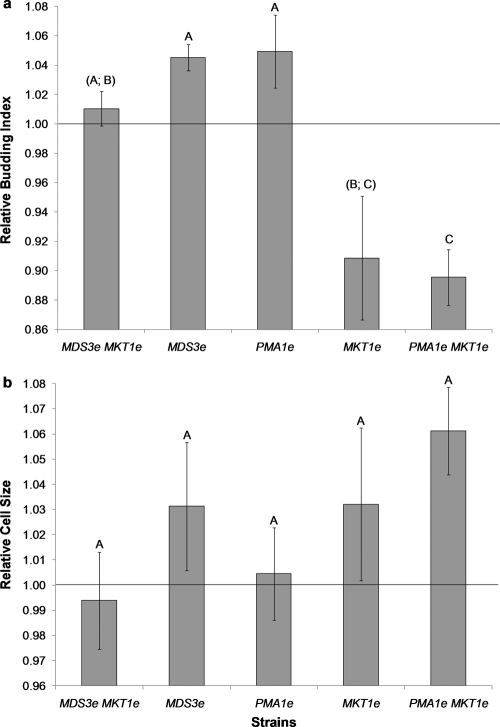

Budding index and cell size measurements.

Both intracellular pH and rate of glucose uptake have been shown to affect the entry of yeast into the cell division cycle (4, 26). To determine whether PMA1e and MKT1e slow the cell division cycle, we measured cell sizes and calculated budding indexes for the different strains. The PMA1e MKT1e double mutant presented the lowest budding index value relative to that of the progenitor strain (0.90 ± 0.02), although it was not significantly different from that observed for the MKT1e strain (Fig. 5a). No significant difference in cell size was observed among the strains carrying evolved alleles (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Relative budding index and cell size measurements for yeast strains carrying evolved alleles. Bars represent the mean budding index values (a) and cell sizes (b) of strains carrying evolved alleles relative to the values obtained for the progenitor strain. Values for strains with the same capital letters above the bars are not significantly different from each other (by the Tukey HSD test with 95% simultaneous confidence intervals). Error bars, ±1 standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Competitions in low-glucose medium.

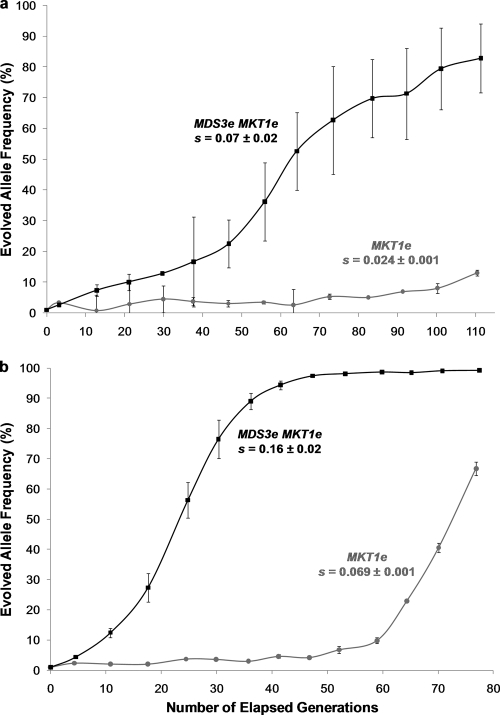

To quantify the fitness effects of the MKT1 and MDS3 mutations prior to and after the diauxic shift, extended competition experiments were performed. Yeast strains carrying MKT1e or both MKT1e and MDS3e were set to compete against a strain that carried only ancestral alleles (progenitor strain) under two different serial transfer protocols. The short-transfer regimen aimed to maintain the cultures under constant fermentative growth, while the long-transfer regimen was designed to maximize the periods of respiratory growth. Under both regimens, the frequencies of the MKT1e and MDS3e MKT1e strains were observed to increase (Fig. 6). The MKT1e strain was previously known to present a fitness deficit compared to the progenitor strain during fermentative growth. Therefore, the fact that the frequency of this strain also increased marginally under the short-transfer protocol might suggest that the competing strains were actually reaching post-diauxic-shift growth stages, where the beneficial effect of MKT1e would begin to appear. (We suspect that a shorter propagation period between transfers would have exposed the fitness deficit due to MKT1e, but this was not tested.) Under the long-transfer protocol, emphasizing respiratory growth, the MDS3e MKT1e double mutant strain displayed a much greater fitness advantage over the progenitor strain than did the strain carrying only the MKT1e allele (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Changes in the frequencies of strains carrying evolved alleles in competition experiments against the progenitor strain. The progenitor strain was set to compete with yeast strains with an MDS3e MKT1e or an MKT1e genotype in a low-glucose environment. In the initial competition mix, the progenitor strain was set as a majority in relation to the strains carrying evolved alleles (100:1). The competition cultures were propagated under either the short-transfer regimen, which aimed to maintain the competing strains under constant fermentative growth (a), or the long-transfer regimen, which aimed to maximize the periods of respiratory growth (b). s values represent the mean selection coefficients of the strains with evolved alleles relative to the progenitor strain. Error bars, ±1 standard error of the mean (n = 3, except for MKT1e in panel b [n = 2]).

Predicting evolutionary substitution at base 89 of MKT1.

With the aim of recapitulating the appearance, spread, and fixation of the MKT1e mutation, haploid yeast strains carrying the MDS3e allele or only ancestral alleles (progenitor strain) were propagated in a low-glucose environment under conditions that favored respiratory growth. Sequencing of the MKT1e SNP region at the endpoint of the experiment revealed that two of the three replicate populations with an MDS3e genetic background carried an allele with a point mutation at the same site as the MKT1e allele. In one of the populations (replicate 1), the evolved allele was identical to the MKT1e allele, with an adenine exchanged for a guanine nucleotide at position 89, which predicts a nonsynonymous replacement of an aspartic acid by a glycine residue in the protein. The allele that had evolved in the second population (replicate 2), designated MKT1e-2, had a mutation at the same site as MKT1e, but the adenine nucleotide was instead replaced by a cytosine, which predicts a nonsynonymous replacement of the aspartic acid by an alanine residue. No mutations within the sequenced MKT1e SNP region were observed for the third MDS3e replicate population (replicate 3) or for any of the populations with a “progenitor” genetic background. An assessment of changes in allelic frequencies throughout the experiments showed that the fitness advantage conferred by the MKT1e-2 allele was lower than that conferred by the MKT1e allele within an MDS3e genetic background. The MDS3e MKT1e-2 genotype had a selection coefficient (s) of 0.09 relative to the MDS3e background genotype, while an s value of 0.12 relative to the MDS3e background genotype was observed for the MDS3e MKT1e genotype (Fig. 7a and 8a).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used genome-wide expression measurements and measured several physiological parameters to elucidate the negative epistatic interaction between the evolved adaptive alleles of PMA1 and MKT1 and the positive epistatic interaction between the evolved alleles of MDS3 and MKT1. The experiments showed that these interactions occur in entirely different ways. The interaction between PMA1e and MKT1e is mediated by an alteration in intracellular pH, while the interaction between MDS3e and MKT1e is mediated by changes in gene regulation, where the most important downstream effect is likely to be that on the rate of glucose transport. The family of hexose transporter (HXT) genes characterized in S. cerevisiae includes 20 members, but only 7 of these genes (HXT1 to -7) encode functional glucose transporters. A strain lacking these seven HXT genes is unable to grow in glucose, and overexpression of these genes has been shown to increase glucose uptake and the fitness of yeast strains (31, 32). As described here, the evolved allele of MKT1 caused a decrease in the expression of four of the seven HXT genes responsible for glucose uptake. This downregulation would be expected to reduce the rate of glucose uptake and to be especially detrimental in a low-glucose environment. The decrease in glucose uptake, associated with the cost of the overexpression of mitochondrial genes, could explain the lower fitness of MKT1e during fermentation prior to the diauxic shift in a low-glucose environment.

In contrast, the observed upregulation of HXT genes likely conveys the increased fitness associated with the MDS3e allele at pre-diauxic-shift stages in a low-glucose environment. An additive effect is seen for the expression of most HXT genes in the MDS3e MKT1e double mutant, since it presented levels intermediary between those observed for the single mutants. MDS3e therefore appears to ameliorate the growth defect observed for MKT1e in pre-diauxic-shift stages by raising the expression of HXT genes to levels above those observed for the progenitor strain. A candidate mediator for the effects of MDS3e and MKT1e on the expression of hexose transporters is the transcription factor Mig2. The MDS3e genotype was associated with a 2-fold (2.1 ± 0.1) increase in the expression of MIG2 relative to that for the progenitor strain, while the MDS3e MKT1e and MKT1e genotypes presented relative expression values of 1.52 ± 0.06 and 0.91 ± 0.01, respectively, all of which were significantly different from each other (by the Tukey HSD test with 95% simultaneous confidence intervals). No significant differences in expression levels were found for MIG1, a closely related gene with which MIG2 works to regulate the expression of many glucose-repressed genes, including several hexose transporters (17). Although these two zinc finger proteins have been shown to bind similar DNA motifs (22), Mig1 acts as the main effector in the repression of most coregulated genes (39). Thus, it is plausible that increased expression of MIG2 might result in some displacement of Mig1 from regulatory binding sites, alleviating the repression of target genes. In fact, the differences in MIG2 expression levels observed across the genotypes studied closely approximate the pattern described for HXT genes whose expression is dependent on glucose concentrations (i.e., HXT1, HXT2, HXT3, and HXT4). The gene expression profiles obtained do not, however, provide insight into how MDS3e or MKT1e may affect the expression of the MIG2 gene. No significant differences in expression levels were observed for RGT1, a gene described as the main regulator of MIG2 expression, or for other known upstream effectors, such as MTH1 or STD1 (17, 39). Furthermore, the increased expression of HXT genes associated with MDS3e may also work to maximize the expression of mitochondrial genes induced by MKT1e late in the growth cycle. Consistent with this interpretation, the upregulation of many mitochondrial genes in the MDS3e MKT1e background was even greater than that observed for the MKT1e single mutant. Overall, MDS3e and MKT1e interact synergistically to confer increased fitness throughout the whole growth cycle on yeast populations in a low-glucose environment.

The PMA1e allele exerts an effect on MKT1e opposite to that of the MDS3e allele: PMA1e reduces the fitness benefits of MKT1e in a low-glucose environment. As shown by the gene expression profiles, the evolved allele of PMA1 does not have a significant effect on gene expression. Instead, its main phenotypic effect is a decrease of about 0.6 unit in the intracellular pHs of yeast populations (from a pHi of 6.79 ± 0.02 to a pHi of 6.23 ± 0.03). Intracellular pH stability is critical for yeast cells, since enzymes that catalyze metabolic reactions have their optimum pHs at a neutral range (23). As previously reported (1), the PMA1e mutation does not have a significant fitness impact by itself. How, then, is the effect of PMA1e on MKT1e manifested? We propose a model in which the effects of reduced expression of HXT genes caused by MKT1e are exacerbated by the low intracellular pH associated with PMA1e, delaying entry into the cell division cycle. This model is consistent with the lower budding index and larger cell size observed for the PMA1e MKT1e strain than for other strains, although these values were not significantly different from those observed for the MKT1e strain. An important function of intracellular pH in yeast cells is to act as a signal mediating the activation of the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway and progression through the cell cycle in the presence of glucose (4). When glucose is metabolized, there is a rise in intracellular pH, which results in the assembly of vacuolar proton pumps and helps to activate the PKA pathway. Notably, progression through the cell cycle in yeast is also affected by the rate of glucose uptake. For example, a genetically engineered yeast strain expressing only one hexose transporter conferring reduced glucose uptake was observed to have enlarged cells and a 75% decrease in the budding index (26). Hence, decreased rates of glucose uptake coupled with lower intracellular pH may lead to an uncoupling of the glycolytic rate and growth in the PMA1e MKT1e double mutant, slowing the entry of cells into the division cycle. Although this model remains to be tested, it should be noted that these results parallel what is observed in fast-growing tumor cells, where an elevated intracellular pH is found to be a common feature (24). In fact, the expression of the yeast PMA1 gene in monkey and mouse fibroblasts has been shown to increase cell proliferation. The activity of the PMA1 H+-ATPase in these cells raised the intracellular pH above basal levels and was correlated with increased tumorigenicity (28, 29).

An essential goal of this study was to test the evolutionary importance of the positive interaction by recapitulating the evolution of MKT1e in experimental populations. Our prediction was that the MKT1e allele would emerge via spontaneous mutation and would rise in frequency only in the presence of MDS3e. The positive epistatic interaction between MDS3e and MKT1e is clearly evident in the competition experiments, where the fitness benefit of MKT1e is enhanced in the presence of MDS3e in both the shorter and longer transfer regimens. The ultimate confirmation of the importance of the MKT1e mutation was the recapitulation of the evolutionary substitution at base position 89 of this gene. Based on our data, the presence of MDS3e is expected to facilitate this predicted change when respiration predominates, i.e., during the prolonged post-diauxic-shift stage of the long-transfer regimen in our experiment. Consistent with expectations, the MKT1e mutation occurred, and a mutant allele rose to high frequency, in two of the three replicate populations with an MDS3e genetic background but in none of the replicates with an MDS3a background. Although the amino acid replacement observed in the second replicate was not the same as that of MKT1e (alteration from D to A instead of from D to G), this mutation also resulted in the replacement of the aspartic acid residue by a neutral amino acid. This second mutation, MKT1e-2, conferred a lower fitness advantage than did MKT1e, suggesting that it represents a less potent form of MKT1 than MKT1e but a more potent form than the ancestral allele of MKT1. Taken together, the recapitulation of the appearance and spread of the MKT1 mutation in yeast populations provides a clear example of how epistasis can play a defining role in shaping trajectories of adaptation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 19 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson J. B., et al. 2010. Determinants of divergent adaptation and Dobzhansky-Muller interaction in experimental yeast populations. Curr. Biol. 20:1383–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benni M. L., Neigeborn L. 1997. Identification of a new class of negative regulators affecting sporulation-specific gene expression in yeast. Genetics 147:1351–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis D. A., Bruno V. M., Loza L., Filler S. G., Mitchell A. P. 2002. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dechant R., et al. 2010. Cytosolic pH is a second messenger for glucose and regulates the PKA pathway through V-ATPase. EMBO J. 29:2515–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Demogines A., Smith E., Kruglyak L., Alani E. 2008. Identification and dissection of a complex DNA repair sensitivity phenotype in baker's yeast. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeRisi J. L., Iyer V. R., Brown P. O. 1997. Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science 278:680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dettman J. R., Sirjusingh C., Kohn L. M., Anderson J. B. 2007. Incipient speciation by divergent adaptation and antagonistic epistasis in yeast. Nature 447:585–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Visser J., Elena S. 2007. The evolution of sex: empirical insights into the roles of epistasis and drift. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dimitrov L. N., Brem R. B., Kruglyak L., Gottschling D. E. 2009. Polymorphisms in multiple genes contribute to the spontaneous mitochondrial genome instability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C strains. Genetics 183:365–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eden A., Simchen G., Benvenisty N. 1996. Two yeast homologs of ECA39, a target for c-Myc regulation, code for cytosolic and mitochondrial branched-chain amino acid aminotransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 271:20242–20245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernandes A. R., Sa-Correia I. 2001. The activity of plasma membrane H+-ATPase is strongly stimulated during Saccharomyces cerevisiae adaptation to growth under high copper stress, accompanying intracellular acidification. Yeast 18:511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerber A. P., Herschlag D., Brown P. O. 2004. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2:e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Griswold C. K., Masel J. 2009. Complex adaptations can drive the evolution of the capacitor PS1+, even with realistic rates of yeast sex. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang D. W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim H. S., Fay J. C. 2009. A combined cross analysis reveals genes with drug-specific and background-dependent effects on drug sensitivity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 183:1141–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kispal G., Steiner H., Court D. A., Rolinski B., Lill R. 1996. Mitochondrial and cytosolic branched-chain amino acid transaminases from yeast, homologs of the myc oncogene-regulated Eca39 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24458–24464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuttykrishnan S., Sabina J., Langton L. L., Johnston M., Brent M. R. 2010. A quantitative model of glucose signaling in yeast reveals an incoherent feed forward loop leading to a specific, transient pulse of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:16743–16748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee H., et al. 2008. Incompatibility of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes causes hybrid sterility between two yeast species. Cell 135:1065–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee S., et al. 2009. Learning a prior on regulatory potential from eQTL data. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liti G., et al. 2009. Population genomics of domestic and wild yeasts. Nature 458:337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lunzer M., Golding G., Dean A. M. 2010. Pervasive cryptic epistasis in molecular evolution. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lutfiyya L., et al. 1998. Characterization of three related glucose repressors and genes they regulate in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 150:1377–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madshus I. H. 1988. Regulation of intercellular pH in eukaryotic cells. Biochem. J. 250:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oberhaensli R., et al. 1986. Biochemical investigation of human tumours in vivo with phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Lancet ii:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ortlund E. A., Bridgham J. T., Redinbo M. R., Thornton J. W. 2007. Crystal structure of an ancient protein: evolution by conformational epistasis. Science 317:1544–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otterstedt K., et al. 2004. Switching the mode of metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO Rep. 5:532–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozcan S., Johnston M. 1999. Function and regulation of yeast hexose transporters. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:554–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perona R., Portillo F., Giraldez F., Serrano R. 1990. Transformation and pH homeostasis of fibroblasts expressing yeast H super(+)-ATPase containing site-directed mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:4110–4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perona R., Serrano R. 1988. Increased pH and tumorigenicity of fibroblasts expressing a yeast proton pump. Nature 334:438–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Phillips P. C. 2008. Epistasis—the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9:855–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reifenberger E., Freidel K., Ciriacy M. 1995. Identification of novel HXT genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals the impact of individual hexose transporters on glycolytic flux. Mol. Microbiol. 16:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rossi G., Sauer M., Porro D., Branduardi P. 2010. Effect of HXT1 and HXT7 hexose transporter overexpression on wild-type and lactic acid producing Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Microb. Cell Fact. 9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanjuan R., Cuevas J. M., Moya A., Elena S. F. 2005. Epistasis and the adaptability of an RNA virus. Genetics 170:1001–1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Serrano R., Kielland-Brandt M., Fink G. 1986. Yeast plasma membrane ATPase is essential for growth and has homology with (Na+ + K+), K+- and Ca2+-ATPases. Nature 319:689–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trindade S., et al. 2009. Positive epistasis drives the acquisition of multidrug resistance. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valli M., et al. 2006. Improvement of lactic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by cell sorting for high intracellular pH. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5492–5499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Verwaal R., et al. 2002. HXT5 expression is determined by growth rates in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 19:1029–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weigert C., Steffler F., Kurz T., Shelhammer T. H., Methner F. 2009. Application of a short intracellular pH method to flow cytometry for determining Saccharomyces cerevisiae vitality. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5615–5620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Westholm J., et al. 2008. Combinatorial control of gene expression by the three yeast repressors Mig1, Mig2 and Mig3. BMC Genomics 9:601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.