Abstract

A putative glycoside phosphorylase from Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. pacificus was recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli, after codon optimization and chemical synthesis of the encoding gene. The enzyme was purified by His tag chromatography and was found to be specifically active toward trehalose, with an optimal temperature of 80°C. In addition, no loss of activity could be detected after 1 h of incubation at 65°C, which means that it is the most stable trehalose phosphorylase reported so far. The substrate specificity was investigated in detail by measuring the relative activity on a range of alternative acceptors, applied in the reverse synthetic reaction, and determining the kinetic parameters for the best acceptors. These results were rationalized based on the enzyme-substrate interactions observed in a homology model with a docked ligand. The specificity for the orientation of the acceptor's hydroxyl groups was found to decrease in the following order: C-3 > C-2 > C-4. This results in a particularly high activity on the monosaccharides d-fucose, d-xylose, l-arabinose, and d-galactose, as well as on l-fucose. However, determination of the kinetic parameters revealed that these acceptors bind less tightly in the active site than the natural acceptor d-glucose, resulting in drastically increased Km values. Nevertheless, the enzyme's high thermostability and broad acceptor specificity make it a valuable candidate for industrial disaccharide synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

Due to its nonreducing nature, trehalose (α-glucosyl-1,1-α-glucoside) has a number of exceptional properties. Although it can serve as a carbon source, as a signaling molecule, or as a component of cell wall glycolipids, it is mostly known for its osmoprotectant properties (11). This feature has been acknowledged by the biotechnological industry, and trehalose is nowadays used to store thermolabile enzymes, to protect unstable molecules such as antibodies at ambient temperatures, to maintain organoleptic properties of dried or processed foods, to preserve cells, tissues, and even organs, and to improve flower shelf life (18).

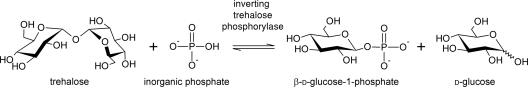

In vivo, trehalose catabolism proceeds predominantly through hydrolysis by trehalase but can also occur through phosphorolysis by trehalose phosphorylase (TP). With the latter enzyme, the organism has the benefit that one of the glucose monomers is phosphorylated (Fig. 1), thereby relieving the need for ATP to enter the glycolytic pathway. Two types of TP exist, each with a different reaction mechanism (10). The retaining TP (EC 2.4.1.231) belongs to family GT4 (7) and generates α-d-glucose-1-phosphate. It is mainly found in mushrooms such as Agaricus bisporus (36) and Schizophyllum commune (14). The inverting TP (EC 2.4.1.64), in contrast, belongs to family GH65 (7) and catalyzes the formation of β-d-glucose-1-phosphate (βGlc1P). It was first discovered in the alga Euglena gracilis (5) and has since been reported in both fungi and bacteria. Prokaryotic sources include Micrococcus varians (21), Thermoanaerobacter brockii (25), Bacillus stearothermophilus (17), and Paenibacillus (38). Furthermore, a BLAST search with the putative TP from Propionibacterium acnes (NCBI YP_055814.1) has revealed the presence of homologous sequences in a wide range of archaea and bacteria, distributed along diverse bacterial phyla such as Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chlorobi (green sulfur bacteria), and Cyanobacteria (4).

Fig. 1.

Reaction scheme of inverting trehalose phosphorylase (EC 2.4.1.64).

Because of the high energy content of a glycosyl phosphate, phosphorolytic reactions are reversible and can thus be exploited for synthetic purposes in vitro (22). With the inverting TP, for example, the synthesis of trehalose analogues such as α-galactosyl-1,1-α-glucoside has been reported (8), a product that shows potential as prebiotic in food preparations as it shows inhibitory effects on intestinal disaccharidases (20). Interestingly, the glycosyl donor used in these reactions is much cheaper than the nucleotide sugars required by glycosyl transferases, which could be crucial for commercial success. For the application of enzymes in the industrial production of new disaccharides, however, two characteristics are essential: a high stability at a process temperature of typically 60°C, and a high catalytic efficiency on the alternative acceptor substrates.

Thanks to recent developments in (meta)genomics, marine environments are increasingly investigated as potential sources of novel enzymes (19, 31). Remarkable or unusual bioprocesses are performed by these biocatalysts due to habitat-related characteristics such as salt tolerance, hyperthermostability, barophilicity, and cold adaptivity, which can be desirable features from a biotechnological perspective. One promising source of thermostable enzymes is the marine organism Carboxydibrachium pacificum (29), recently renamed as Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. pacificus (12). It was isolated from a hot vent in the Okinawa Trough and has an optimal growth temperature of 70°C. The sequencing of its genome has revealed the presence of a putative inverting TP, annotated as “glycosyl hydrolase family 65 central catalytic domain” (NCBI accession no. ABXP00000000). In this work, we describe the recombinant expression and characterization of the enzyme. In particular, its substrate specificity was examined in detail by a combination of kinetic measurements and molecular modeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth conditions, and chemicals.

Escherichia coli XL10 Gold was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA) and used as the host for recombinant expression. It was routinely grown at 37°C on LB medium (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 10 g/liter NaCl, pH 7.0) supplemented with 0.1 g/liter ampicillin.

The gene coding for the putative trehalose phosphorylase from Carboxydibrachium pacificum DSM 12653 (accession number ZP_05091985), which was recently renamed as Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. pacificus (12), was codon optimized using the program JCat (15) and chemically synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The gene was cloned into the constitutive expression vector pCXP34h (1), which adds a N-terminal His6 tag to the enzyme. The resulting construct is further referred to as pCXCsTP.

Trehalose was kindly provided by Cargill Benelux (Sas van Gent, The Netherlands), while d-lyxose, l-fucose, d-fucose, d-allose, gentiobiose, and melibiose were purchased from Carbosynth (Compton, United Kingdom). The donor β-d-glucose-1-phosphate was prepared as previously described (34). All other chemicals and medium components were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ) unless stated otherwise.

Enzyme expression and purification.

A glycerol stock of E. coli XL10 Gold, transformed with the pCXCsTP vector, was used to inoculate a 5-ml preculture of LB medium supplemented with ampicillin. After overnight growth, fresh LB medium with ampicillin was inoculated with this preculture at a 2% (vol/vol) concentration. This culture was grown for 8 h at 37°C, allowing the constitutive expression of the enzyme. Subsequently, the cells were collected by centrifugation and the pellet was frozen overnight at −20°C. Enzyme extraction was performed by thawing the cell pellet for 15 min on ice, followed by dissolution in lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8). After 30 min of incubation on ice, lysis was completed by sonication and the cellular debris was removed by centrifugation.

For enzyme purification, the supernatant was applied to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) that was equilibrated with 3 column volumes of buffer A (300 mM NaCl in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 8). The resin was rinsed with 4 column volumes of buffer B (buffer A supplemented with 20 mM imidazole), after which the enzyme was eluted with 2 column volumes of buffer C (buffer A supplemented with 500 mM imidazole). Finally, the elution buffer was replaced by 30 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) buffer, pH 6, by using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter unit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) with a 30K molecular weight cutoff. The purity of the enzyme was checked by SDS-PAGE using the LMW-SDS marker kit (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) as the standard.

Enzyme assays.

The enzyme activity has been measured in both directions of the equilibrium reaction. Phosphorolytic activity was quantified by measuring the glucose released from 30 mM disaccharide in 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) with the GOD-POD assay (37). The disaccharide substrates do not interfere with this assay, while glucose can be specifically detected starting from a concentration of 10 μM. In the synthetic direction, the release of inorganic phosphate from 30 mM βGlc1P and 30 mM glucose in 50 mM MES buffer (pH 6) was measured with the phosphomolybdate assay (13). The glycosyl donor β-d-glucose-1-phosphate does not interfere with this assay, while inorganic phosphate can be specifically detected starting from a concentration of 200 μM. Reactions were monitored for 10 min at 60°C in a heating block with sampling at regular intervals, followed by immediate cooling on ice.

The influence of pH on enzyme activity was measured in the range of pH 4 to 9 using acetate (pH 4 to 5.5), MES (pH 5 to 6.5), MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) (pH 6 to 8), and Tris (pH 7.5 to 9) buffers. The optimal temperature was determined by performing the enzyme reaction in a heating block set at temperatures in the range of 37 to 95°C. Temperature stability was examined by incubating purified enzyme for 1 h in a gradient thermocycler (Biometra, Goettingen, Germany) set to a temperature range of 55 to 85°C, followed by 15 min of cooling to 16°C. The residual activity of the enzyme was determined in the synthetic direction using the standard conditions described above.

Substrate screening was performed with 30 mM βGlc1P and 500 mM acceptor (30 mM for glucose and d-fucose). Although the donor substrate was highly pure, there were still trace amounts (<1%) of glucose present. This was sufficient to generate a background activity of 5.6% compared to the reference activity on 30 mM glucose. All measured initial velocities were corrected for this background activity. For the disaccharides, activity was also investigated by determining the transfer ratio. This was done in analogy to the method employed by Maruta et al. (25) using trehalose, melibiose, or gentiobiose as the acceptor and analyzing trisaccharide formation by thin-layer chromatographic (TLC) analysis. TLC was performed on a Kieselgel 60 plate (Merck, Germany) developed twice with a solvent of 6:4:1 butanol (BuOH)-pyridine-water. Visualization was done by spraying 20% sulfuric acid in methanol (MeOH) on the plate, followed by incubation at 110°C for 10 min.

For glucose and the best alternative acceptors, the kinetic parameters were determined. This was done by performing a typical Michaelis-Menten experiment with 10 substrate concentrations in triplicate. The kinetic parameters were calculated from the initial velocities by Hanes-Woolf linearization (16). The concentration of the enzyme was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard.

Homology modeling and molecular docking.

A homology model of C. subterraneus TP (CsTP) was generated with SwissModel (3, 6) by using the crystal structure of the closely related T. brockii TP (35) as the template. The binding of trehalose was simulated by ligand docking with AutoDock Vina (33). A search space of 12 × 12 × 12 Å was used, spanning the enzyme's active site. The structures of ligand and receptor were formatted with AutoDockTools 1.5.4 (27). The C-5–C-6 bonds and the bonds around the glycosidic oxygen of the substrate were set as rotatable, while none of the enzyme's side chains were treated as flexible. The structure and docking were visualized with PyMol. The docking algorithm resulted in 9 binding modes with comparable energies. From these, the most accurate model was selected on the basis of known interactions in the active site of carbohydrate-active enzymes (10).

RESULTS

Cloning and expression of the gene.

The genome of Carboxydibrachium pacificum DSM 12653 (Caldanaerobacter subterraneus subsp. pacificus) has recently been decoded by shotgun sequencing (NCBI accession no. ABXP00000000). One of the predicted open reading frames (ORFs), annotated as “glycosyl hydrolase family 65 central catalytic domain,” shares a high sequence identity with the inverting TP from Thermoanaerobacter brockii (24), a thermostable enzyme able to use a range of monosaccharides as substitutes for glucose in disaccharide synthesis (9). At the protein level, a sequence identity of 82% could be detected. The C. subterraneus enzyme consists of 783 amino acids, with a calculated molecular mass of 90.487 kDa and a theoretical pI of 5.42.

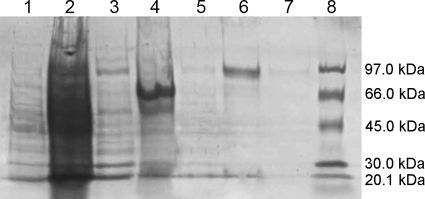

The sequence of the putative TP gene was optimized for expression in E. coli with the program JCat (www.jcat.de) (15) and chemically synthesized. The resulting DNA sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing and showed 75% identity to the wild-type sequence. The optimized gene was then cloned into the vector pCXP34h (1), which adds a His6 tag to the N terminus of the protein, and constitutively expressed in E. coli. By means of affinity chromatography, the enzyme could be purified to apparent homogeneity in a single step (Fig. 2). This purified preparation was used for the determination of the enzymatic properties.

Fig. 2.

SDS-PAGE of the fractions obtained during purification of CsTP. Lanes: 1, flow-through; 2, wash fraction 1; 3, wash fraction 2; 4, wash fraction 3; 5, wash fraction 4; 6, elution fraction 1; 7, elution fraction 2; 8, molecular mass marker.

Initially, the purified enzyme was assayed for phosphorolytic activity on kojibiose, maltose, and trehalose, i.e., the three specificities that have been reported for family GH65 (10). These experiments confirmed that the putative gene indeed codes for a trehalose phosphorylase, since the enzyme efficiently degraded trehalose (specific activity of 39.8 ± 3.5 U/mg) but showed no measurable activity on maltose or kojibiose.

Enzymatic properties of TP.

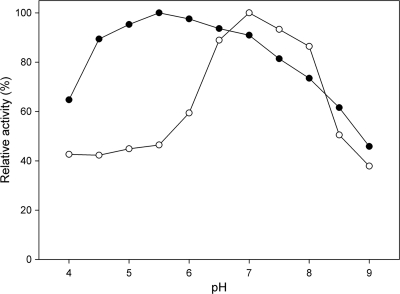

The influence of pH on the enzyme activity was determined in the range of pH 4 to 9 in both the phosphorolytic and synthetic directions (Fig. 3). This revealed a broad pH interval where enzyme activity remains reasonably high, especially in the synthetic direction where activity is over 90% in the range of pH 4.5 to 7. The optimum is slightly different for both reaction directions, with a higher optimum (pH 7) for phosphorolysis, as is typical for both retaining and inverting trehalose phosphorylases (9, 28).

Fig. 3.

The effect of pH on trehalose phosphorylase activity in the phosphorolytic (○) and synthetic (•) directions. Assay conditions were 30 mM glucose and βGlc1P or trehalose and phosphate in a 10-min reaction at 60°C. Activity was quantified by measuring the released inorganic phosphate or glucose, respectively. The buffers used (50 mM) were acetate (pH 4 to 5.5), MES (pH 5 to 6.5), MOPS (pH 6 to 8), and Tris (pH 7.5 to 9).

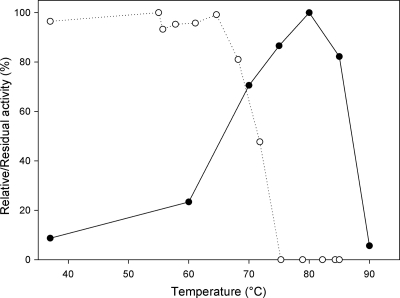

The influence of temperature on activity as well as stability was also determined (Fig. 4). Maximal activity was observed at 80°C, which is 10°C higher than the temperature optimum of the TP from T. brockii (24). In addition, the enzyme was found to be completely stable for 1 h up to 65°C. Furthermore, the temperature at which 50% residual activity remains after 1 h of incubation is 72°C, making it the most stable GH65 disaccharide phosphorylase yet reported (9, 17).

Fig. 4.

The effect of temperature on activity (•) and stability (○) of TP measured in the synthetic direction. Activity was assayed in a heating block in a 10-min reaction from 37°C to 90°C. Stability was tested by incubating the enzyme in a gradient PCR machine for 1 h and measuring the residual activity in a standard assay at 60°C for 10 min. All reactions were performed in the synthetic direction.

Substrate specificity.

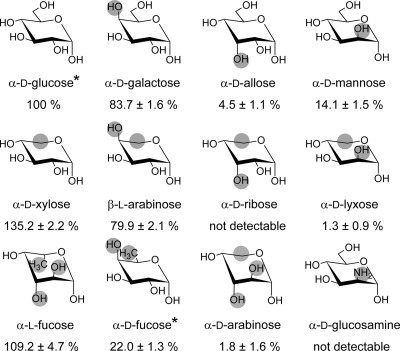

The substrate specificity was determined in the synthetic direction, using βGlc1P as the donor and various mono- and disaccharides as acceptors. The specificity for alternative monosaccharide acceptors was rationalized by testing a range of glucose epimers and their corresponding pentoses. In addition, some molecules that were previously reported to be successful acceptors for other trehalose phosphorylases were tested. A high concentration (500 mM) of each acceptor was used in the reaction to maximize the chance of detecting a response. For glucose, however, strong substrate inhibition is observed at this concentration, reducing the activity to 49.1% of the activity at the saturating concentration of 30 mM. Therefore, all activities were compared with the maximum activity on 30 mM glucose, which was found to be 44.6 ± 2.9 U/mg. In addition, d-fucose contained inorganic phosphate, which generated a high background in the activity assay and has thus also been limited to a concentration of 30 mM. The results of these experiments are presented in Fig. 5, where the acceptor structures are shown together with their relative activities. This reveals that the enzyme is active on nearly all of the alternative acceptors. Some, such as d-xylose and l-fucose, are better than the natural acceptor d-glucose, with relative activities of 135% and 109%, respectively. The other acceptors can be classified as good (d-galactose and l-arabinose), intermediate (d-mannose and d-fucose), or bad (d-allose, d-arabinose, and d-lyxose). However, d-fucose was tested at a concentration of only 30 mM, suggesting that it is also one of the best acceptors. The only acceptors on which no detectable activity could be measured are d-ribose and d-glucosamine.

Fig. 5.

Chair representations and relative activity of all tested monosaccharides where structural differences from the wild-type acceptor glucose are marked in gray. All structures are shown in the 4C1 conformation; an asterisk indicates that only 30 mM acceptor was used instead of 500 mM. Activity was determined in a standard 10-min reaction at pH 6 and 60°C. All values were corrected for the background activity and compared to the maximal activity (with 30 mM glucose).

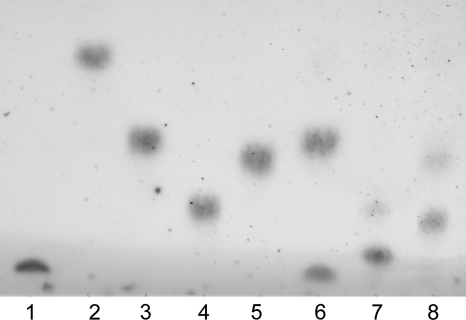

None of the disaccharides seemed to function as an acceptor when analyzed on the basis of initial reaction velocity. For melibiose and gentiobiose, this is in contrast to what has been reported for the TP of T. brockii (25). Therefore, the activity on these substrates was also investigated by measuring trisaccharide formation after 24 h of incubation. The reaction samples were analyzed by TLC, indeed showing trisaccharide formation for the substrates melibiose and gentiobiose but not for trehalose, in accordance with the TP from T. brockii (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

TLC analysis of the synthetic reaction with trehalose, melibiose, or gentiobiose as the acceptor. Lanes: 1, βGlc1P standard; 2, glucose standard; 3, trehalose standard; 4, melibiose standard; 5, gentiobiose standard; 6, trehalose reaction; 7, melibiose reaction; 8, gentiobiose reaction. Kieselgel 60 plate, developed twice with a solvent of 6:4:1 BuOH-pyridine-water.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the TP from C. subterraneus has a relatively wide acceptor specificity. For the best acceptors, the kinetic parameters were determined by performing a Michaelis-Menten experiment in triplicate (Table 1). However, d-fucose was not included in these studies because it contained inorganic phosphate that hindered activity tests at higher concentrations. The kcat values for the monosaccharides d-xylose, l-arabinose, l-fucose, and d-galactose were found to be approximately the same as that for the wild-type acceptor glucose, while their Km values are drastically higher. Consequently, the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme drops with factors 5, 21, 45 and 54, respectively. For the other monosaccharide acceptors, the Km could not even be determined, as the enzyme was not yet saturated at the highest acceptor concentration. For mannose, for example, the Michaelis-Menten graph remained linear up to a concentration of 2 M.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of CsTP for the best alternative acceptors

| Substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km(s−1mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-Glucose | 59.0 ± 5.4 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 17 ± 4 |

| d-Xylose | 64.3 ± 4.1 | 20.3 ± 2.9 | 3.17 ± 0.50 |

| l-Arabinose | 51.4 ± 6.1 | 64.8 ± 8.3 | 0.793 ± 0.139 |

| d-Galactose | 54.0 ± 5.7 | 171.5 ± 26.2 | 0.315 ± 0.058 |

| l-Fucose | 68.1 ± 3.8 | 183.4 ± 13.8 | 0.371 ± 0.035 |

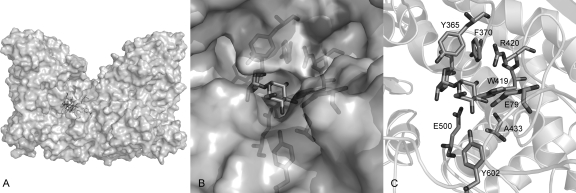

Enzyme substrate interactions.

To investigate the enzyme-substrate interactions, a homology model of the enzyme was constructed, using the crystal structure of the closely related (82% amino acid identity) T. brockii trehalose phosphorylase (35) as the template. Subsequently, the binding of the natural substrate trehalose was simulated by automated docking (Fig. 7). From these experiments, it can be inferred that E500 is the catalytic acid and that the transition state in subsite −1 would be stabilized by the so-called hydrophobic platform (26) created by F370. For binding of the acceptor in subsite +1, the C-3 hydroxyl group seems to form the most interactions (W419, E79, and the backbone oxygen of A433), followed by the C-2 hydroxyl group (W419 and R420) and the C-4 hydroxyl group (Y602 and E79). The latter residue is located in a loop of the other monomer that makes up part of the active site. Finally, the C-6 hydroxyl group points toward the entrance of the active site and should thus have the highest degree of flexibility.

Fig. 7.

Homology model of CsTP (A) Dimeric structure. (B) Active site representation with surface. (C) Enzyme-substrate interactions. The structure was determined with SwissModel based on the structure of TP from T. brockii and visualized with PyMol. Trehalose was docked with AutoDock Vina.

DISCUSSION

Interest in marine extremophiles has increased recently, resulting in the identification of novel biocatalysts from different enzyme classes, such as alcohol dehydrogenases, proteases, lipases, and carbohydrate-active enzymes (32). The enzyme described in this paper originates from the organism C. subterraneus subsp. pacificus, which was isolated from a submarine hot vent (29). It was confirmed to be an inverting TP and its enzymatic properties were determined. Interestingly, the enzyme's optimal temperature for activity was found to be 80°C, which is 10°C higher than the optimal temperature for the growth of the source organism (29). Furthermore, the enzyme was shown to remain stable for 1 h at a 5°C higher temperature than any disaccharide phosphorylase from family GH65 reported to date. This high stability is of importance for the application of the enzyme in industrial di- or oligosaccharide synthesis.

The substrate specificity was examined in detail to determine which alternative acceptors could be efficiently employed in such a process (Fig. 5). These results reveal the broad acceptor specificity of the enzyme compared to previously reported trehalose phosphorylases. The TP from Euglena gracilis, for example, has a much stricter acceptor specificity, as it is only active on 6-deoxyglucose and d-xylose as substitutes for d-glucose (23). On d-mannose and d-galactose, which are intermediate to good acceptors for CsTP, the enzyme of E. gracilis is completely inactive. The TP from Catellatospora feruginea, in turn, has been tested for 52 monosaccharides and related compounds, but activity could be observed only on d-xylose and d-fucose (2). In addition to the high Km values for these alternative acceptors, their kcat values were considerably lower than that for d-glucose, while CsTP is highly active on many monosaccharides. The most closely related TP, i.e., the enzyme from T. brockii, also has the most similar specificity (9). However, its activity on d-galactose, l-arabinose, and l-fucose seems to be drastically lower (20 to 40%) than that on d-glucose. This could be explained by the use of a different experimental setup, since the specificity was reported as the transfer ratio after 24 h, which is also influenced by the thermodynamic parameters of the reaction.

When rationalizing the observed specificity of CsTP, it is clear that the specificity for the orientation of the C-4 hydroxyl group is quite loose, as high activity could be detected on both d-galactose and l-arabinose. In addition, d-fucose is also a good acceptor since it already generates a relative activity of 22% at a concentration of only 30 mM. Docking and modeling studies corroborated these observations (Fig. 7). Indeed, the C-4 hydroxyl group was found to be located near the entrance of the active site, having potential interactions only with E79 and Y602. When the group is oriented axially, the hydrogen bond with Y602 is probably disrupted but this could be compensated for by a new interaction with R420. For the C-2 hydroxyl group, the specificity is stricter, as is apparent from the 14% relative activity on mannose and the very low activity (1.3%) on d-lyxose. Furthermore, no activity could be observed on d-glucosamine, in contrast to what was reported for TP of T. brockii (9), as was previously mentioned. An axial orientation of this hydroxyl group would reduce the distance to R420 to less than 2 Å, causing a steric clash and presumably forcing the substrate into a tilted position.

The specificity for the orientation of the C-3 hydroxyl group is the strictest. On d-allose, 4.5% activity was measured and no activity remained on its corresponding pentose d-ribose. The distance of the catalytic acid to the acceptor C-3 atom is estimated to be only 3.3 Å, so a downward orientation of its hydroxyl group would severely hinder substrate binding. For the hexoses d-glucose (100%) and d-galactose (84%), their corresponding pentoses d-xylose (135%) and l-arabinose (80%) have greater or almost equal activity levels, indicating that the C-6 hydroxyl group is not essential for activity. Indeed, this substituent is pointing toward the entrance of the active site, with only E79 nearby for a possible interaction. However, when the orientation of the stricter hydroxyl groups at C-2 and C-3 is altered, no activity can be detected on the corresponding pentoses. This suggests that the C-6 hydroxyl group becomes more important when the acceptor is forced in a tilted position.

Surprisingly, high activity on l-fucose (109%) was observed, in stark contrast to the near absence of activity on d-arabinose, which has a very similar structure. Furthermore, l-fucose was even found to be the acceptor with the highest kcat value. Although both monosaccharides are drawn in the 4C1 conformation in Fig. 5, it has been reported that l-fucose and α-d-arabinose nearly always adopt the 1C4 conformation, while β-d-arabinose is in an equilibrium state between 4C1 and 1C4 (30). It thus cannot be predicted in which conformation these monosaccharides bind in the active site and how this would influence the enzyme-substrate interactions. Consequently, crystallographic analysis of the respective complex structures would be extremely valuable for the rationalization of the observations reported here.

For disaccharide acceptors, only substitutions at C-6 of glucose seemed to be allowed, in accordance to what has been reported for the closely related TP from T. brockii (25). Investigating the architecture of the active site indicates that such a substitution could indeed be accommodated, as the additional glycosyl ring would be positioned at—or even through—the entrance of the active site (Fig. 7B). However, the fact that activity could be detected only after prolonged reaction times suggests that the catalytic efficiency on these disaccharides is very low.

Conclusion.

In this work, a novel inverting trehalose phosphorylase from the marine bacterium Caldanaerobacter subterraneus is described. Determination of the enzymatic properties revealed that this TP is the most stable GH65 disaccharide phosphorylase yet reported, with a temperature optimum of 80°C. The determination of its relative activity on a range of monosaccharides revealed that specificity is most strict at C-2 and especially C-3 of the acceptor. In contrast, specificity is much looser for the C-4 hydroxyl group and the presence of a substituent at C-5 seems to be of importance only when the orientation of the strictest hydroxyl groups is altered. The difference in activity on the various monosaccharides was found to be caused by a difference in Km values, while the kcat values are rather similar. Interestingly, the activity data could be corroborated by examining the enzyme-substrate interactions through molecular docking of trehalose in a homology structure of the enzyme. In summary, this biocatalyst's high stability and broad acceptor specificity make it a suitable candidate for the industrial production of novel disaccharides, which could be used as prebiotic sweeteners in food preparations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by a PhD grant (SB71279, SB73279) from the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation through Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT-Vlaanderen).

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aerts D., Verhaeghe T., De Mey M., Desmet T., Soetaert W. 2010. A constitutive expression system for high-throughput screening. Eng. Life Sci. 11:10–19 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aisaka K., Masuda T., Chikamune T., Kamitori K. 1998. Purification and characterization of trehalose phosphorylase from Catellatospora ferruginea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62:782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avonce N., Mendoza-Vargas A., Morett E., Iturriaga G. 2006. Insights on the evolution of trehalose biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 6:109–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Belocopitow E., Maréchal L. R. 1970. Trehalose phosphorylase from Euglena gracilis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 198:151–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bordoli L., et al. 2009. Protein structure homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL workspace. Nat. Protoc. 4:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cantarel B. L., et al. 2009. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chaen H., et al. 2001. Efficient enzymatic synthesis of disaccharide, alpha-d-galactosyl alpha-d-glucoside, by trehalose phosphorylase from Thermoanaerobacter brockii. J. Appl. Glycosci. 48:135–137 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaen H., et al. 1999. Purification and characterization of thermostable trehalose phosphorylase from Thermoanaerobium brockii. J. Appl. Glycosci. 46:399–405 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Desmet T., Soetaert W. 2011. Enzymatic glycosyl transfer: mechanisms and applications. Biocatal. Biotransform. 29:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elbein A., Pan D, Y., Pastuszak T. I., Carroll D. 2003. New insights on trehalose: a multifunctional molecule. Glycobiology 13:17R–27R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fardeau M. L., et al. 2004. Isolation from oil reservoirs of novel thermophilic anaerobes phylogenetically related to Thermoanaerobacter subterraneus: reassignment of T. subterraneus, Thermoanaerobacter yonseiensis, Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis and Carboxydibrachium pacificum to Caldanaerobacter subterraneus gen. nov., sp nov., comb. nov as four novel subspecies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:467–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gawronski J. D., Benson D. R. 2004. Microtiter assay for glutamine synthetase biosynthetic activity using inorganic phosphate detection. Anal. Biochem. 327:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goedl C., Griessler R., Schwarz A., Nidetzky B. 2006. Structure and function relationships for Schizophyllum commune trehalose phosphorylase and their implications for the catalytic mechanism of family GT-4 glycosyltransferases. Biochem. J. 397:491–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grote A., et al. 2005. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W526–W531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hanes C. S. 1932. Studies on plant amylases: the effect of starch concentration upon the velocity of hydrolysis by the amylase of germinated barley. Biochem. J. 26:1406–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inoue Y., Ishii K., Tomita T., Yatake T., Fukui F. 2002. Characterization of trehalose phosphorylase from Bacillus stearothermophilus SK-1 and nucleotide sequence of the corresponding gene. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:1835–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iturriaga G., Suarez R., Nova-Franco B. 2009. Trehalose metabolism: from osmoprotection to signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10:3793–3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy J., Marchesi J., Dobson A. 2008. Marine metagenomics: strategies for the discovery of novel enzymes with biotechnological applications from marine environments. Microb. Cell Fact. 7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim H. M., Chang Y. K., Ryu S. I., Moon S. G., Lee S. B. 2007. Enzymatic synthesis of a galactose-containing trehalose analogue disaccharide by Pyrococcus horikoshii trehalose-synthesizing glycosyltransferase: inhibitory effects on several disaccharidase activities. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 49:98–103 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kizawa H., Miyagawa K. I., Sugiyama Y. 1995. Purification and characterization of trehalose phosphorylase from Micrococcus varians. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59:1908–1912 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luley-Goedl C., Nidetzky B. 2010. Carbohydrate synthesis by disaccharide phosphorylases: reactions, catalytic mechanisms and application in the glycosciences. Biotechnol. J. 5:1324–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maréchal L. R., Belocopitow E. 1972. Metabolism of trehalose in Euglena gracilis. J. Biol. Chem. 247:3223–3228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maruta K., et al. 2002. Gene encoding a trehalose phosphorylase from Thermoanaerobacter brockii ATCC 35047. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:1976–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Maruta K., et al. 2006. Acceptor specificity of trehalose phosphorylase from Thermoanaerobacter brockii: production of novel nonreducing trisaccharide, 6-O-alpha-d-galactopyranosyl trehalose. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 101:385–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nerinckx W., Desmet T., Claeyssens M. 2003. A hydrophobic platform as a mechanistically relevant transition state stabilising factor appears to be present in the active centre of all glycoside hydrolases. FEBS Lett. 538:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanner M. F. 1999. Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17:57–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwarz A., Goedl C., Minani A., Nidetzky B. 2007. Trehalose phosphorylase from Pleurotus ostreatus: characterization and stabilization by covalent modification, and application for the synthesis of alpha,alpha-trehalose. J. Biotechnol. 129:140–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sokolova T. G., et al. 2001. Carboxydobrachium pacificum gen. nov., sp nov., a new anaerobic, thermophilic, CO-utilizing marine bacterium from Okinawa Trough. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sundararajan P. R., Rao V. S. R. 1968. Theoretical studies on the conformation of aldopyranoses. Tetrahedron 24:289–295 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trincone A. 2011. Marine biocatalysts: enzymatic features and applications. Mar. Drugs 9:478–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trincone A. 2010. Potential biocatalysts originating from sea environments. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 66:241–256 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trott O., Olson A. J. 2010. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31:455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Van der Borght J., Desmet T., Soetaert W. 2010. Enzymatic production of beta-d-glucose-1-phosphate from trehalose. Biotechnol. J. 5:986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Van Hoorebeke A., et al. 2010. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction studies of inverting trehalose phosphorylase from Thermoanaerobacter sp. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66:442–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wannet W. J. B., et al. 1998. Purification and characterization of trehalose phosphorylase from the commercial mushroom Agaricus bisporus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1425:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Werner W., Rey H. G., Wielinge H. 1970. Properties of a new chromogen for determination of glucose in blood according to GOD/POD-method. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 252:224 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yuj M. H. Y. H. January 2005. Novel microorganism, maltose phosphorylse, trehalose phosphorylase, and process for producing these. WO2005003343. [Google Scholar]