Abstract

Two legionellosis outbreaks occurred in the city of Rennes, France, during the past decade, requiring in-depth monitoring of Legionella pneumophila in the water network and the cooling towers in the city. In order to characterize the resulting large collection of isolates, an automated low-cost typing method was developed. The multiplex capillary-based variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) (multiple-locus VNTR analysis [MLVA]) assay requiring only one PCR amplification per isolate ensures a high level of discrimination and reduces hands-on and time requirements. In less than 2 days and using one 4-capillary apparatus, 217 environmental isolates collected between 2000 and 2009 and 5 clinical isolates obtained during outbreaks in 2000 and 2006 in Rennes were analyzed, and 15 different genotypes were identified. A large cluster of isolates with closely related genotypes and representing 77% of the population was composed exclusively of environmental isolates extracted from hot water supply systems. It was not responsible for the known Rennes epidemic cases, although strains showing a similar MLVA profile have regularly been involved in European outbreaks. The clinical isolates in Rennes had the same genotype as isolates contaminating a mall's cooling tower. This study further demonstrates that unknown environmental or genetic factors contribute to the pathogenicity of some strains. This work illustrates the potential of the high-throughput MLVA typing method to investigate the origin of legionellosis cases by allowing the systematic typing of any new isolate and inclusion of data in shared databases.

INTRODUCTION

Legionella pneumophila, an aerobic, non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacillus, is the main etiologic agent of legionellosis, a severe respiratory disease transmitted by inhalation of aqueous aerosols. L. pneumophila can be found in freshwater sources, such as rivers, lakes, or ponds, where it multiplies in free-living amoebae and ciliated protozoa. The bacteria also have a widespread distribution in human-made environments (1). Most legionellosis outbreaks are linked to contaminated hot water systems or cooling towers (16). The bacteria can persist in these artificial aquatic environments through the formation of biofilms that protect Legionella populations from temperature changes and biocide treatment (25). Protozoa serve as a reservoir for legionellae, and it is thought that growth within amoebae enhances pathogenicity (6, 34).

L. pneumophila is a very diverse and heterogeneous species which is divided into three subspecies (L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila, L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, and L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei). L. pneumophila can be differentiated into 17 serogroups (sg), sg1 being responsible for more than 98% of the reported legionellosis cases (12). The L. pneumophila population is considered clonal, and the adaptation of clonal complexes (CC) to a specific ecological niche was suggested (14). Studies reported that L. pneumophila is capable of plasmid-mediated recombination exchange of DNA material (13) and demonstrated the occurrence of horizontal genetic transfer (9, 10, 14). Conclusions about the L. pneumophila population structure might be biased since the strains investigated are usually recovered from clinical cases or human-made environments. The L. pneumophila population is supposed to be much more diverse, and the observed clonal complexes may be a nonrandom set that represents specific lineages adapted to human habitats (32).

Due to widespread L. pneumophila occurrence in both natural and artificial aquatic systems, it is essential, in order to allow the implementation of prevention measures, to identify potential environmental sources of infection by comparing clinical and environmental isolates (31, 35). The investigation and characterization of large collections require low-cost typing procedures. The current typing method recommended by the European EWGLI Consortium is a multilocus sequence typing (MLST)-like protocol called sequence-based typing (SBT) (18, 30). This approach is highly portable and widely used to perform epidemiological surveys and outbreak investigation (27) owing to the existence of databases accessible over the internet. However, SBT remains tedious and time-consuming, as it requires the sequencing of both strands of seven gene fragments. For this reason, its use as a first-line assay for large-scale investigations seems precluded. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) is a PCR-based typing method that relies on the variability found in some tandemly repeated DNA sequences which represent sources of genetic polymorphism (37). Ten VNTRs suitable for L. pneumophila MLVA genotyping were previously reported (29), and a selection of 8 loci comprising Lpms01, Lpms03, Lpms13, Lpms17, Lpms19, Lpms33, Lpms34, and Lpms35 and compatible with low-resolution DNA sizing equipment (such as agarose gels) was proposed. The MLVA protocol based on these eight VNTRs and called MLVA-8Orsay was useful for both epidemiological studies and analysis of population structure (28, 29). Indeed, recent work showed that a majority of clinical strains were distributed into a limited number of CCs defined by MLVA, called VNTR analysis CC (VACC) and characterized by epidemic strains such as Paris (VACC1), Philadelphia-1 (VACC2), and Corby (VACC9) (38).

In the city of Rennes, one of the largest cities in the west of France, with a population of 200,000 inhabitants, two legionellosis outbreaks occurred in the past 10 years. The first outbreak happened in autumn 2000 and caused 22 legionellosis cases, including 4 deaths. Public health authorities adopted a plan in March 2001 to assess and prevent Legionella-associated risks. Despite the implementation of this plan, a second outbreak occurred in January 2006 and led to 2 deaths among the 8 diagnosed cases (4). In the context of water networks and cooling towers monitoring for the presence of L. pneumophila, isolates are regularly collected from multiple sites representative of the whole water supply system in Rennes. Here we genotyped 217 isolates collected in Rennes between 2000 and 2009, revealing that strains involved in the two outbreaks were not related to the few clones which colonize the whole water supply system in this city. For this, we automated the MLVA procedure by coamplifying 12 VNTRs (MLVA-12Orsay) in a single PCR and performed fluorescent capillary electrophoresis. Compared to MLVA-8Orsay, the new protocol provides increased informativity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A total of 320 isolates were used, including 95 isolates from the EWGLI reference collection. This collection contains clinical and environmental isolates originating from 10 countries and is composed of one epidemiologically unrelated panel of 74 isolates (panel 1), one epidemiologically related panel of 16 isolates (panel 2), and one stability panel of 5 isolates (panel 3) (17). All isolates from this collection belong to serogroup 1 (sg1) and have been characterized extensively by other genotypic and phenotypic methods. In addition, three reference strains for which the genome has been sequenced (Philadelphia-1, Paris, and Lens) were used as controls. The type strain of L. pneumophila, Philadelphia-1 (NCTC 11192), was obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures, London, United Kingdom. The Lens and Paris reference strains have been deposited by the French National Reference Center for Legionella in Lyon, France, in the EWGLI collection (EUL 160 and EUL146, respectively). Five clinical isolates came from two epidemic cases that occurred in autumn 2000 and winter 2006 in Rennes. Two hundred and seventeen environmental isolates collected from human-made sources (cooling towers and water distribution systems) in Rennes between 2000 and 2009 were selected from the collection maintained by the Laboratoire d'étude et de Recherche en Environnement et Santé (LERES) in Rennes, France (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

DNA extraction.

Strains were cultured at least 2 days at 36 ± 2°C on buffered charcoal-yeast extract (BCYE) with l-cysteine. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). DNA concentration was measured using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Labtech, Palaiseau, France) and adjusted to 3 ng/μl with water.

Selection of VNTRs.

The typing procedure is based on the analysis of 12 VNTRs, 8 of which were published by Pourcel and colleagues (29). Four additional VNTRs (Table 1) were selected from the four available L. pneumophila genomes using the Microorganisms Tandem Repeats Database (20): Lpms38 (8-bp repeat unit), Lpms39 (6-bp repeat unit), Lpms40 (6-bp repeat unit), and Lpms44 (6-bp repeat unit). They were selected among the 10 microsatellites with a 6- to 8-bp repeat unit and at least a 60% average internal conservation and showing at least two different alleles among the four sequenced genomes and were tested on panel 1 from the EWGLI collection. Lpms17 was excluded from the present MLVA scheme because of its low informativity, whereas Lpms31, which is difficult to type on agarose gel, was incorporated. As a result, the extended MLVA scheme, MLVA-12Orsay, includes 12 VNTRs: eight are minisatellites (Lpms01, Lpms03, Lpms13, Lpms19, Lpms31, Lpms33, Lpms34, and Lpms35) and 4 are microsatellites (Lpms38, Lpms39, Lpms40, and Lpms44).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used and VNTRs analyzed in this study

| VNTR | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Repeat unit size (bp) | Expected size (bp) (no. of repeats) for strain Philadelphia-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lpms01 | Lpms01R | GCATATGACAAAGCCTTGGC | 45 | 494 (8) |

| Lpms01F | TGAATTTCTCCCTCTTGCTTG | |||

| Lpms01F-NED | NED-TGAATTTCTCCCTCTTGCTTG | |||

| Lpms03 | Lpms03R | TGATGGTCTCAATGGTTCCG | 96 | 942 (8) |

| Lpms03F | GGACAAACAACCAATGAAGC | |||

| Lpms03F-VIC | VIC-GGACAAACAACCAATGAAGC | |||

| Lpms13 | Lpms13R | GCATCGGACTGAGCAAAGTA | 24 | 793 (11) |

| Lpms13F | CTCACCAGGATGCTTTGTCG | |||

| Lpms13F-NED | NED-CTCACCAGGATGCTTTGTCG | |||

| Lpms19 | Lpms19R | TCCAGAGGCTCTGGATTATC | 21 | 128 (4) |

| Lpms19F | GAACTATCAGAAGGAGGCGA | |||

| Lpms19F-VIC | VIC-GAACTATCAGAAGGAGGCGA | |||

| Lpms31 | Lpms31R | ATCGCCTAATTGCCGCCTA | 45 | 1,043 (17) |

| Lpms31F | CCTCGCAAGCCTATGTGG | |||

| Lpms31F-FAM | FAM-CCTCGCAAGCCTATGTGG | |||

| Lpms33 | Lpms33R | CGAGGAAATCTTCTTCAGCC | 125 | 317 (1) |

| Lpms33F | GACACCACAGCAGTTTGAAC | |||

| Lpms33F-VIC | VIC-GACACCACAGCAGTTTGAAC | |||

| Lpms34 | Lpms34R | ATGCAGGATGTTTGCGCATG | 125 | 265 (1) |

| Lpms34F | AAGGAATAAGGCGCAGCAC | |||

| Lpms34F-FAM | FAM-AAGGAATAAGGCGCAGCAC | |||

| Lpms35 | Lpms35R | TATCAACCTCATCATCCCTG | 18 | 205 (3) |

| Lpms35F | GAATCTGAAACAGTTGAGGATG | |||

| Lpms35F-PET | PET-GAATCTGAAACAGTTGAGGATG | |||

| Lpms38 | Lpms38R | GGATTGCCTTGGGCATTAAT | 8 | 264 (3) |

| Lpms38F | CCTATCAACAGATGACGCTT | |||

| Lpms38F-NED | NED-CCTATCAACAGATGACGCTT | |||

| Lpms39 | Lpms39R | CCAACTCCTCAACGCAACAA | 6 | 79 (6) |

| Lpms39F | CTTGACGAAGTAGGTGTGGG | |||

| Lpms39F-PET | PET-CTTGACGAAGTAGGTGTGGG | |||

| Lpms40 | Lpms40R | TTACCCAAGCCCTTATTGCG | 6 | 198 (4) |

| Lpms40F | TAGATCTCTTGCCGAGCTTC | |||

| Lpms40F-FAM | FAM-TAGATCTCTTGCCGAGCTTC | |||

| Lpms44 | Lpms44R | TTATGCGAGAGTTTCATGA | 6 | 173 (9) |

| Lpms44F | GCTACTGCAGCAACATCC | |||

| Lpms44F-NED | NED-GCTACTGCAGCAACATCC |

MLVA typing.

Primers were designed to be able to simultaneously amplify all 12 loci, taking into account the allele size range of each locus previously evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Range and HGDI for individual or combined VNTR loci

| VNTR(s) | Minimum allele size (no. of repeats, expected size [bp]) | Maximum allele size (no. of repeats, expected size [bp]) | No. of alleles or no. of genotypes | HGDI | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lpms01 | 6, 404 | 10, 584 | 6 | 0.6501 | {0.5821,0.7181} |

| Lpms03 | 7, 846 | 8, 942 | 2 | 0.5054 | {0.4928,0.5179} |

| Lpms13 | 3, 601 | 17, 937 | 10 | 0.7790 | {0.7152,0.8428} |

| Lpms19 | 4, 128 | 5, 149 | 2 | 0.2936 | {0.1788,0.4084} |

| Lpms31 | 6, 548 | 20, 1,178 | 12 | 0.8563 | {0.8061,0.9066} |

| Lpms33 | 1, 317 | 5, 817 | 6 | 0.7020 | {0.6196,0.7844} |

| Lpms34 | 1, 265 | 3, 515 | 4 | 0.6649 | {0.6203,0.7096} |

| Lpms35 | 3, 205 | 32, 727 | 17 | 0.8815 | {0.8416,0.9215} |

| Lpms38 | 3, 264 | 19, 392 | 4 | 0.2710 | {0.1389,0.4031} |

| Lpms39 | 6, 79 | 26, 199 | 12 | 0.8301 | {0.7699,0.8902} |

| Lpms40 | 4, 198 | 5, 204 | 2 | 0.5054 | {0.4928,0.5179} |

| Lpms44 | 6, 155 | 18, 227 | 6 | 0.5391 | {0.4512,0.6269} |

| MLVA-12Orsay | 39 | 0.9534a | {0.9234,0.9833} |

Calculated from typing results obtained with the 74 L. pneumophila strains included in panel 1 of the EWGLI collection.

The 12 VNTR loci were amplified in a unique multiplex PCR using the genotyping kit Typlegio ceeramTools (Ceeram, Nantes, France). Briefly, this kit includes forward primers labeled at the 5′ end with either 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM), 2′-chloro-7′-phenyl-1,4-dichloro-6-carboxyfluorescein (VIC), 2′-chloro-5′-fluoro-7′,8′-fused phenyl-1,4-dichloro-6-carboxyfluorescein (NED), or PET (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Reverse primers were synthesized unlabeled and tailed (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). The use of reverse-tailed primers, which promotes the addition of a nontemplated A to the product, efficiently avoided the so-called +A peak artifact (3). The multiplex PCR was performed in a 15-μl final volume using the Qiagen multiplex PCR kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The reaction mixture contained 2 μl template DNA (3 ng/μl), 7.5 μl of 2× multiplex PCR mastermix, and 5.5 μl of primer mix. The PCR was run on a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) using the following conditions: initial denaturation cycle for 15 min at 95°C, 15 cycles of touchdown PCR (30 s at 95°C; 60 s at 82°C, with a 1.2°C drop in temperature each next cycle; 70 s at 72°C); and 15 cycles of long-range PCR (30 s at 95°C; 60 s at 64°C; 70 s at 72°C, with a 5-s increase in time each next cycle), with a final 10 min at 72°C. PCR fragments were purified using Qiagen DyeEx plates (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Then, 2 μl of purified PCR product was combined with 7.75 μl HiDi formamide and 0.25 μl GS1200LIZ (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). The samples were run on the ABI3130 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Electrophoresis was performed using a 50-cm capillary filled with performance-optimized polymer 7 (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France) at 60°C for 6,200 s with a running voltage of 12 kV and an injection time of 10 s at an injection voltage of 1.6 kV.

Automated binning was performed with the GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Each bin is characterized by the allele mean size plus or minus 10% of the unit size length. Insertion or deletion mutations sometimes arise in flanking regions or directly in tandem repeats and affect the amplicon size. Therefore, we assessed a confidence interval (CI) to overcome these sequence polymorphisms.

Data analysis.

Each VNTR locus was identified according to color and automatically assigned a size by the GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). This size was then converted into an allele designation associated with a quality index. Intermediate-size alleles (which may result from intermediate-size repeat units or from small deletions in the flanking sequence) were reported as half size (0.5). The typing datum file was imported into BioNumerics version 6.5 (Applied-Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

A complete strain allele string expressed as its allelic profile corresponding to the number of repeats at each VNTR was constructed in the order Lpms01, Lpms03, Lpms13, Lpms19, Lpms31, Lpms33, Lpms34, Lpms35, Lpms38, Lpms39, Lpms40, and Lpms44. The genotype of the Philadelphia-1 strain deduced from its genomic sequence NC_002942 is 8-8-11-4-17-1-1 3-3-6-4-9 and that of strain Paris NC_006368 is 7-7-10-4-9.5-4-2-17-3-13-5-6.

Repeatability of the multiplex PCR and of the size measurement by the capillary electrophoresis device was tested in two ways. The 98 isolates of the validation group were typed twice independently using the same DNA samples. In addition, the three reference strains Lens (EUL160), Paris (EUL146), and Philadelphia (NCTC11192) were typed eight times independently using the same DNA samples.

The Hunter-Gaston diversity index (HGDI) (23), an application of Simpson's index of diversity (33), was used as a polymorphism index for individual or combined VNTR loci. CI were calculated as described previously (21). The unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering method was run using the categorical coefficient (also called Hamming's distance). A cutoff value of 60% similarity was applied to define clusters. The minimum spanning tree was produced in BioNumerics, allowing the creation of missing links and scaling with member count. The logarithm scale was used when drawing branches.

RESULTS

Automated multiplex capillary-based MLVA assay development.

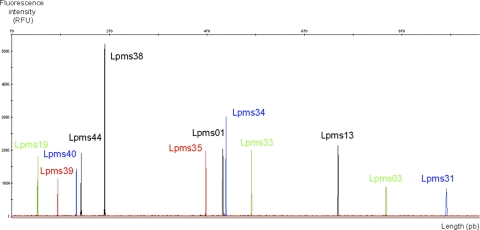

The new optimized primers and the high-stringency PCR protocol yielded clean electrophoretic profiles without artifactual peaks, such as stutter, spike, or shoulder peaks (Fig. 1). Half-size alleles were observed for Lpms01, Lpms31, and Lpms39. In previous reports, correct assignment of unit repeats was not simple for Lpms31 because of the high frequency of these half-size alleles, and therefore, use of the higher-precision capillary electrophoresis equipment is mandatory for this locus.

Fig. 1.

Electrophoregram showing PCR amplicons of all 12 dye-colored coamplified VNTR loci separated by size and color with capillary electrophoresis.

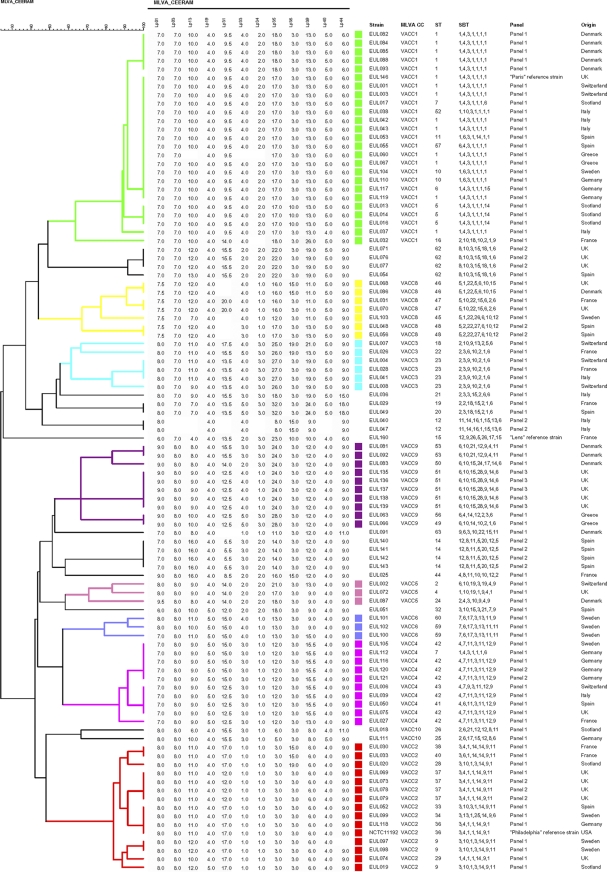

The Study Group on Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM) refers to two categories of criteria to define the quality of a typing method: performance and convenience criteria (36). The performance criteria include marker stability, typeability (T value), discriminatory power combined with epidemiological concordance, and reproducibility (including repeatability). These criteria were evaluated and tested on 98 strains of the EWGLI reference collection, of which 74 are unrelated (panel 1) (17). The dendrogram in Fig. 2 displays the MLVA data and the clustering of strains, allowing an assessment of the different criteria.

Fig. 2.

Dendrogram deduced from the clustering analysis of the 98 strains from panel 1 of the EWGLI collection using MLVA-12Orsay. MLVA clusters (VACC) of 3 or more genotypes are shown with colors.

Performance criteria. (i) Stability.

The stability panel composed of 5 isolates of the Corby strain (EUL135 to EUL139) showed the same MLVA allelic profile.

(ii) T value.

Out of 1,176 expected datum values, 21 were missing and are shown as an absent value in the dendrogram shown in Fig. 2, corresponding to a typeability, or T value, of 98.22%. Two isolates (EUL040 and EUL047) accounted for 10 of these missing data. Excluding these two isolates, the T value of MLVA-12Orsay is 99.3%.

(iii) Discriminatory power (HGDI).

Indices of discrimination (HGDI value) were calculated for the panel of 74 unrelated strains for each VNTR and for the two combinations of loci (MLVA-12Orsay and MLVA-8Orsay) (Table 2). The MLVA-12Orsay index is 0.9534, a significant increase over the previous MLVA-8Orsay scheme (HGDI = 0.9189). The new protocol distinguished 7 additional genotypes (39 versus 32). This improved resolution was provided primarily by Lpms38, which generated 4 new genotypes.

(iv) Epidemiological concordance.

The epidemiologically related panel included 16 isolates divided into 6 groups comprising isolates with an established epidemiological link. Members of each group had the same unique MLVA code.

(v) Repeatability.

The 98 isolates of the validation group were typed twice and showed the same genotypic profile. The observed sizes at each locus for the eight trials are listed in Tables S2, S3, and S4 in the supplemental material. All values are included in their respective confidence interval, showing that the described typing protocol was reproducible.

Clustering was performed, and a cutoff value of 60%, corresponding to a maximum of 5 differences out of 12 VNTRs, was applied, defining 10 clusters corresponding to MLVA clonal complexes (VACC) observed with MLVA-8Orsay in a previous work (38). Nine additional genotypes were observed with the EWGLI collection (Fig. 2). The polymorphism provided by the new markers of MLVA-12Orsay (Lpms31, Lpms38, Lpms39, Lpms40, and Lpms44) induced minor changes in the clusters. EUL029, EUL036, and EUL049 were not included in VACC3; EUL071, EUL076, EUL077, and EUL054 formed a group dissociated from VACC1; EUL025 and EUL051 were not included in VACC5.

Long-term epidemiological monitoring of L. pneumophila population in Rennes.

The MLVA-12Orsay assay was used to type 217 environmental isolates collected from anthropic sources (cooling towers and water distribution systems) between 2000 and 2009 in Rennes and 5 clinical isolates from two epidemic cases that occurred in autumn 2000 and winter 2006 in the same city. The 222 isolates were resolved into 14 MLVA types and distributed into 4 clusters, VACC1, VACC2, VACC6, and VACC8 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). All the tested isolates of VACC1 (22/34), VACC2 (13/16), and VACC6 (128/170) were sg1. The two isolates of VACC8 were non-sg1. Surprisingly, a low diversity (HGDI = 0.5372) was observed, due largely to the high prevalence of VACC6 isolates (77% of all the isolates) in this subset and particularly of genotype 9 (87% of the VACC6 isolates and 67% of all the isolates).

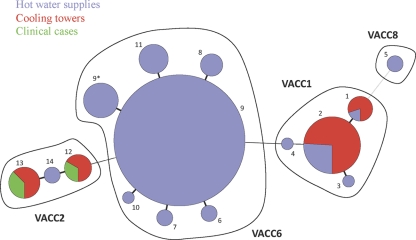

Members of VACC1 (34 isolates) with 4 MLVA genotypes were frequent in cooling towers (Fig. 3). Genotype 2 represented the largest part of VACC1 (80%) and included ST1 isolates (sequence-based type [SBT] 1,4,3,1,1,1,1 [with allele numbers separated by commas]), among which was the endemic Paris strain. Genotype 2 isolates were harvested predominantly in cooling towers (24 isolates out of 31, 77%) and in hot water systems (Fig. 3). This genotype was detected profusely in hospital A's cooling tower and had an extensive colonizing period (from 2001 to 2009). Moreover, genotype 1, also present in hospital A's cooling tower, was likely to have derived from genotype 2 by a change at VNTR Lpms35. No other genotype was found in this cooling tower. Two other variants of genotype 2, each represented by a single isolate, were found in the water supplies of two gymnasiums: genotype 3, an Lpms39 variant, and genotype 4, an Lpms31 and Lpms34 variant. None of the genotypes grouped in VACC1 were reported as outbreak strains in Rennes.

Fig. 3.

Minimum spanning tree of the 222 L. pneumophila isolates of the Rennes, France, study using MLVA-12Orsay (distribution according to sampling source). Each circle represents an MLVA genotype (the genotype number is indicated; genotype 9* corresponds to genotype 9 with a missing value at Lpms13). The VACC assignment is represented in bold.

VACC2 with three MLVA genotypes (12, 13, and 14) comprised all 5 clinical isolates and 11 environmental isolates, of which 9 (81%) came from cooling towers (Fig. 3). Genotype 13 is the genotype of reference strain NCTC11192 Philadelphia-1 (ST36, 3,4,1,1,14,9,1). The 5 clinical isolates were previously typed by other methods (unpublished data) and were assigned to the same pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) type and to three different SBT sequence types (ST439, 3,4,1,28,14,11,11; ST626, 3,4,1,28,14,11,1; and ST628, 3,4,1, 1,14,13,30). ST439 isolates with MLVA genotype 12 were responsible for two legionellosis cases that occurred during the two outbreaks in 2000 and 2006. The ST626 and ST628 isolates with MLVA genotype 13 were involved in the 2000 outbreak. Epidemiological studies revealed that these isolates were associated with the two cooling towers inside mall A and likely represent a long-term contamination of the mall with the same strain. The main mall cooling tower was colonized by genotype 12 and genotype 13 isolates, whereas only genotype 13 isolates were recovered from the cooling tower of night club A, located inside the mall.

VACC6 is represented here essentially by genotype 9. Six single-locus variants are observed, with genotype 9* differing from 9 by the absence of data at Lpms13 (Fig. 3). All VACC6 isolates were harvested exclusively in hot water systems in diverse facilities, such as schools, swimming pools, spas, hotels, gymnasiums, and malls (Fig. 3), throughout the study period from 2000 to 2009. Genotype 9 was found during each annual sampling campaign. It was sampled from swimming pool A in March 2000 and October 2010 and also from gymnasium A in May 2003 and February 2005. EUL102, a Swedish isolate from the EWGLI collection, also exhibited MLVA genotype 9. Both L0794, an MLVA genotype 9 isolate, and EUL 102 were ST59 (7,6,17,3,13,11,11), which confirmed their genetic relatedness. The six single-locus variants of genotype 9 (shown as 6, 7, 8, 9*, 10, and 11 in Fig. 3) differed at loci Lpms13, Lpms35, and Lpms31 (3, 2, and 1 genotypes, respectively). One of the Lpms13 variants, genotype 8, presented the same MLVA profile as EUL101 (ST60; 7,6,17,3,13,11,9), a strain closely related to genotype 9 strain EUL102, according to SBT typing, illustrating good congruence between MLVA and SBT.

Isolates L1201 and L1202 belonged to VACC8, which also includes the Lorraine strain. They differed from Lorraine type strain EUL070 (ST47; 5,10,22,15,6,2,6) at two markers (Lpms19 and Lpms31), for which PCR amplification failed. L1201 was typed by SBT and was assigned to ST74 (5,1,22,30,6,10,6). This ST has four alleles in common with ST47 and differs by 12, 2, and 9 nucleotide mutations at pilE, mip, and proA, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Automated capillary-based MLVA system, a powerful genotyping tool.

Nederbragt and collaborators described an automated method based upon the MLVA-8Orsay loci. The products of 8 individual PCRs were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis runs (26). We describe here an MLVA-12Orsay assay optimized for capillary electrophoresis analysis, which can be performed in a single PCR. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of a multiplex-based MLVA assay that involves the coamplification of more than nine loci. Taking advantage of the higher sizing precision provided by capillary electrophoresis, we added Lpms31 and four newly identified loci (Lpms38, Lpms39, Lpms40, and Lpms44) to the previous MLVA-8Orsay selection of loci. Lpms17 was excluded because of its lack of informativity.

The clonal complex assignment was realized according to Visca and colleagues (38) in order to allow the distinction of the 10 highlighted CCs. Thus, a cutoff of 60%, which groups in the same CC any isolates that exhibit at least 7 identical markers, was applied. Due to the supplementary information brought with the added markers, some previously VACC-associated isolates were outgrouped with MLVA-12Orsay.

The new VNTRs possess shorter repeat units. Lpms38, despite its low apparent discrimination value (HGDI value = 0.2710) due to the preponderance of the 3-repeat unit (3U) allele (83% of the isolates from EWGLI panel 1 have this allele), allows the differentiation of 2 extra genotypes in VACC2 and 1 extra genotype in VACC1 and VACC8. Its large allele range (from 3 to 19 repeat units) suggests that new alleles could be discovered when studying other L. pneumophila populations. Lpms39 has 12 alleles and a high HGDI value (0.83). Lpms40 presents only 2 alleles, with VACC1, VACC3, and VACC8 sharing the 5U allele and VACC2, VACC4, VACC5, VACC6, and VACC10 sharing allele 4U. Finally, Lpms44 offers no advantage for discrimination, at least in the population investigated here, but shows six alleles from 6U to 18U, suggesting the existence of additional alleles in L. pneumophila.

MLVA-12Orsay shows excellent reproducibility and typeability. Five markers (Lpms01, Lpms31, Lpms35, Lpms38, and Lpms39) could not be amplified in EUL040 and EUL047. Their ST (ST12; 11,14,16,1,15,13,6) is related to that of reference strains Los Angeles-1 ATCC 33156 (11,14,16,25,7,13,F) and Dallas-1E ATCC 33216 (11,14,16,18,15,13,F) belonging to L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri, suggesting that the PCR primers do not perfectly match their genome. Weak amplification for these two isolates was previously reported by Pourcel and colleagues using the primers designed for MLVA-8Orsay (29).

The VNTR markers proved to be stable and epidemiologically concordant. The discrimination power of MLVA-12Orsay is 0.9534, compared to 0.9189 for MLVA-8Orsay. Dendrogram topologies obtained for MLVA-12Orsay and SBT were very congruent. The ESGEM recommends that the diversity value of a genotyping scheme should be at least 0.95. The new MLVA protocol is beyond this prerequisite, even if it still remains less discriminatory than the SBT protocol (HGDI = 0.9608). However, some studies report the difficulty in amplifying the last SBT marker, neuA. Removing this marker, the SBT is significantly less discriminatory (HGDI = 0.9256).

The described technical improvements are a major advance toward a routine and easy use of Legionella genotyping. The four steps of the MLVA procedure (DNA extraction, specific coamplification of the 12 VNTRs in a single multiplex PCR, fragment analysis by capillary electrophoresis, and strain code assignment) were standardized to be usable and understandable by nonexpert users. Finally, MLVA-12Orsay results are delivered as an easily sharable and storable numeric code (http://mlva.u-psud.fr).

Epidemiological monitoring of L. pneumophila population in Rennes.

We investigated strains collected as part of a large-scale epidemiological study to better understand the terms of epidemic outbreaks that occurred in Rennes and to assess the L. pneumophila diversity in Rennes' water supply. It represents the largest time-scale MLVA analysis of L. pneumophila isolates harvested in a local area. Twenty-three percent of the isolates were clustered with VACC1 (Paris lineage, 34 isolates), VACC2 (Philadelphia-1 lineage, 16 isolates) and VACC8 (Lorraine lineage, 2 isolates). All the others gather in the previously defined VACC6 cluster (Fig. 3). VACC1 Paris isolates were harvested mostly in cooling towers (70% of the VACC1 isolates; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), in agreement with a recent investigation in Japan suggesting that the Paris strain is particularly well adapted to cooling towers (2). This clone, assigned to ST1 and variants, has been shown to be very persistent in the environment (24) and to be responsible for sporadic cases as well as for outbreaks reported since 1981 in several countries all over the world (5). Although this CC is colonizing the Rennes' hospital cooling tower, it has not generated reported legionellosis outbreaks. All 5 clinical cases are found in VACC2 (Philadelphia-1 lineage), two with genotype 12 (ST439) and three with genotype 13 (ST626 and ST628). These STs were reported only for the Rennes outbreaks, but they are highly related to the type strain Philadelphia-1. Isolates of the VACC8 Lorraine cluster were harvested twice in a single place, the hot water system of a nursing home. The Lorraine strain itself (ST47) is a highly virulent emerging strain frequently found in Europe (19). It was responsible for 10% of diagnosed cases of Legionnaires' disease in 2009, but it is found rarely in the environment. The two Rennes VACC8 isolates were non-sg1, whereas the Lorraine strains involved in clinical cases were always sg1.

More surprisingly, we observed the large repartition of a unique MLVA clone (VACC6) recovered exclusively from hot water systems. Its distribution was not restricted to a specific neighborhood of the city, as 93% of hot water systems are colonized by VACC6 isolates (Fig. 3). This is, to our knowledge, the first report of such colonization by a single clone in anthropic habitats. The level of contamination of the network is highly variable, since it ranged from 50 to 200,000 CFU/liter (mean, 800) for VACC6 isolates. Moreover, we show that the contamination of the water network is very persistent and presumably resilient to treatments used for decontamination of the networks (50 mg/liter chloride treatment or heat shock), as described by Cooper and Hanlon (8) and Farhat et al. (15). One MLVA genotype 9 isolate from Rennes was analyzed by SBT and assigned to ST59 (7,6,17,3,13,11,11), a ST that has regularly been observed during epidemiological surveys (22, 31) and was responsible for several clinical cases in Great Britain, France, and Canada. Interestingly, the study by Reimer and collaborators showed that ST59 isolates and one-locus-variant ST670 isolates (7,6,17,3,11,11,11) were recovered in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, from water over a period of 17 years but were not involved in clinical cases in that town in the same period. Moreover, in the present study all the tested VACC6 isolates were sg1, suggesting that the clone is potentially pathogenic. In spite of the abundance of this clone in Rennes' water supplies and the pathogenicity of highly similar isolates, it did not trigger the reported outbreaks which were linked to the contamination of cooling towers. Thus, in Rennes, isolates of VACC6, which seem particularly well adapted to water supply facilities, might be less prone to express their pathogenic power than in other niches, a potential illustration of the ecotype theory (7). However, VACC6 may have been involved in sporadic clinical cases not investigated in the present study. During the survey, the number of sporadic cases of legionellosis diagnosed in Rennes was very low (a few cases each year). Whole-genome sequencing and comparison between VACC6 isolates from Rennes and from outbreak-associated strains may shed light on this question (11).

The developed MLVA genotyping assay may represent a decision-making tool to help define targeted and priority risk facilities at which it seems important to act quickly. The present investigation suggests that a major treatment plan of Rennes' water supply is not to be advised since it might result in the recolonization of a different strain with a higher resilience and pathogenic potential.

Evolution of the strains involved in clinical cases.

MLVA typing confirms the likely sources of the two outbreaks as cooling towers in a single mall in Rennes. The 5 isolates are members of a single CC with two MLVA genotypes and 3 STs. ST628 and ST629 isolates, both of MLVA genotype 13, differ at the mip, proA, and neuA markers at 5, 16, and 2 nucleotides, respectively. The ST 439 isolate with MLVA genotype 12 presents the same mip and proA alleles as ST626. Although these SBT loci are supposed to be prone to selection pressure, such a high divergence between alleles at a unique geographical location and during a short period of time could be explained only by horizontal transfer, given the sequence identity observed at the other loci. Thus, it is possible that ST626 diverged from ST628 through acquisition of DNA material from an ST439 isolate.

Conclusion.

We discovered the massive colonization of Rennes water supplies essentially by strains of a single L. pneumophila clonal complex, VACC6. The presence of the major strain (genotype 9) and its variants, identified over a period of 10 years, was not associated with an outbreak of clinical cases. These observations were the result of high-resolution genotyping of more than 200 strains with a fast, efficient, automated, multiplex capillary-based MLVA method. The genotype in the form of a code which facilitates datum transfer and interlaboratory comparison was produced automatically. Such a method will allow the follow-up of a very large population of isolates, opening the way to relevant epidemiological studies as well as investigation of the L. pneumophila population structure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Arlette Rouxel for technical support in the isolation of strains and the Agence Régionale de Santé and the Association pour le Développement de l'Hygiène et de l'épidémiologie en Bretagne of Rennes for their financial support. We thank Norman Fry for providing DNA samples of the EWGLI collection.

D.S., F.L.-H., and B.L. are employees of Ceeram and hold stocks. Patent licensing arrangements exist with D.S., F.L.-H., B.L., and C.P.

Work by G.V. is part of the European Biodefense Laboratory Network (EBLN) supported by the European Defense Agency.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 5 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albert-Weissenberger C., Cazalet C., Buchrieser C. 2007. Legionella pneumophila—a human pathogen that co-evolved with fresh water protozoa. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64:432–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amemura-Maekawa J., Kura F., Chang B., Watanabe H. 2005. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 isolates from cooling towers in Japan form a distinct genetic cluster. Microbiol. Immunol. 49:1027–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballard L. W., et al. 2002. Strategies for genotyping: effectiveness of tailing primers to increase accuracy in short tandem repeat determinations. J. Biomol. Tech. 13:20–29 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Campese C., Jarraud S., Che D. 2007. Legionnaire's disease: surveillance in France in 2005. Med. Mal. Infect. 37:716–721(In French.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cazalet C., et al. 2008. Multigenome analysis identifies a worldwide distributed epidemic Legionella pneumophila clone that emerged within a highly diverse species. Genome Res. 18:431–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cirillo J. D., et al. 1999. Intracellular growth in Acanthamoeba castellanii affects monocyte entry mechanisms and enhances virulence of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 67:4427–4434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohan F. M. 2001. Bacterial species and speciation. Syst. Biol. 50:513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooper I. R., Hanlon G. W. 2010. Resistance of Legionella pneumophila serotype 1 biofilms to chlorine-based disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 74:152–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corrigan R. M., Rigby D., Handley P., Foster T. J. 2007. The role of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG in adherence and biofilm formation. Microbiology 153:2435–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coscolla M., Comas I., Gonzalez-Candelas F. 2011. Quantifying nonvertical inheritance in the evolution of Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:985–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. D'Auria G., Jimenez-Hernandez N., Peris-Bondia F., Moya A., Latorre A. 2010. Legionella pneumophila pangenome reveals strain-specific virulence factors. BMC Genomics 11:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doleans A., et al. 2004. Clinical and environmental distributions of Legionella strains in France are different. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:458–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dreyfus L. A., Iglewski B. H. 1985. Conjugation-mediated genetic exchange in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 161:80–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards M. T., Fry N. K., Harrison T. G. 2008. Clonal population structure of Legionella pneumophila inferred from allelic profiling. Microbiology 154:852–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farhat M., et al. 2010. Development of a pilot-scale 1 for Legionella elimination in biofilm in hot water network: heat shock treatment evaluation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108:1073–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fields B. S., Benson R. F., Besser R. E. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fry N. K., et al. 1999. A multicenter evaluation of genotypic methods for the epidemiologic typing of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1: results of a pan-European study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:462–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaia V., et al. 2005. Consensus sequence-based scheme for epidemiological typing of clinical and environmental isolates of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2047–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ginevra C., et al. 2008. Lorraine strain of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:673–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grissa I., Bouchon P., Pourcel C., Vergnaud G. 2008. On-line resources for bacterial micro-evolution studies using MLVA or CRISPR typing. Biochimie 90:660–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grundmann H., Hori S., Tanner G. 2001. Determining confidence intervals when measuring genetic diversity and the discriminatory abilities of typing methods for microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4190–4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrison T. G., Afshar B., Doshi N., Fry N. K., Lee J. V. 2009. Distribution of Legionella pneumophila serogroups, monoclonal antibody subgroups and DNA sequence types in recent clinical and environmental isolates from England and Wales (2000–2008). Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28:781–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hunter P. R., Gaston M. A. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465–2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawrence C., et al. 1999. Single clonal origin of a high proportion of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 isolates from patients and the environment in the area of Paris, France, over a 10-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2652–2655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murga R., et al. 2001. Role of biofilms in the survival of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable-water system. Microbiology 147:3121–3126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nederbragt A. J., et al. 2008. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of Legionella pneumophila using multi-colored capillary electrophoresis. J. Microbiol. Methods 73:111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olsen J. S., et al. 2010. Alternative routes for dissemination of Legionella pneumophila causing three outbreaks in Norway. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44:8712–8717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pourcel C., Vidgop Y., Ramisse F., Vergnaud G., Tram C. 2003. Characterization of a tandem repeat polymorphism in Legionella pneumophila and its use for genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1819–1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pourcel C., et al. 2007. Identification of variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) sequences in Legionella pneumophila and development of an optimized multiple-locus VNTR analysis typing scheme. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1190–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ratzow S., Gaia V., Helbig J. H., Fry N. K., Lück P. C. 2007. Addition of neuA, the gene encoding N-acylneuraminate cytidylyl transferase, increases the discriminatory ability of the consensus sequence-based scheme for typing Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1965–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reimer A. R., Au S., Schindle S., Bernard K. A. 2010. Legionella pneumophila monoclonal antibody subgroups and DNA sequence types isolated in Canada between 1981 and 2009: laboratory component of national surveillance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:191–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Selander R. K., et al. 1985. Genetic structure of populations of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 163:1021–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simpson E. H. 1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163:688 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Swanson M. S., Hammer B. K. 2000. Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis: a fateful journey from amoebae to macrophages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:567–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tijet N., et al. 2010. New endemic Legionella pneumophila serogroup I clones, Ontario, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:447–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Belkum A., et al. 2007. Guidelines for the validation and application of typing methods for use in bacterial epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(Suppl. 3):1–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. 2009. Multiple locus variable number of tandem repeats analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 551:141–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Visca P., et al. 26 May 2011. Investigation of the Legionella pneumophila population structure by analysis of tandem repeat copy number and internal sequence variation. Microbiology [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1099/mic.0.047258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.