Abstract

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked alkaline phosphatase (GPI-ALP) from the epithelial membrane of the larval midgut of Aedes aegypti was previously identified as a functional receptor of the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry4Ba toxin. Here, heterologous expression in Escherichia coli of the cloned ALP, lacking the secretion signal and GPI attachment sequences, and assessment of its binding characteristics were further investigated. The 54-kDa His tag-fused ALP overexpressed as an inclusion body was soluble when phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) was supplemented with 8 M urea. After renaturation in a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity column, the refolded ALP protein was able to retain its phosphatase activity. This refolded ALP also showed binding to the 65-kDa activated Cry4Ba toxin under nondenaturing (dot blot) conditions. Quantitative binding analysis using a quartz crystal microbalance revealed that the purified ALP immobilized on a gold electrode was bound by the Cry4Ba toxin in a stoichiometry of approximately 1:2 and with high affinity (dissociation constant [Kd] of ∼14 nM) which is comparable to that calculated from kinetic parameters (dissociation rate constant [koff]/binding constant [kon]). Altogether, the data presented here of the E. coli-expressed ALP from A. aegypti retaining high-affinity toxin binding support our notion that glycosylation of this receptor is not required for binding to its counterpart toxin, Cry4Ba.

INTRODUCTION

Cry4Ba δ-endotoxin, which is one of the dipteran-specific Cry-family toxins produced from the spore-forming Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis, is highly toxic to mosquito larvae of Aedes and Anopheles species, vectors of dengue viruses and malarial parasites, respectively (4). This insect specificity is in part due to the occurrence of toxin receptors in the target larval midgut membrane (4). The X-ray crystal structures of Cry4Ba and several other known Cry toxins reveal similar structural features, suggesting that they have the same mode of action for a common toxic effect to their target insect larvae (5). They are composed of three structurally and functionally distinctive domains (domains I to III). The N-terminal α-helical bundle (domain I) and the β-sheet prism (domain II) have been shown to be membrane pore-forming and receptor-binding domains, respectively. However, the functional role of the C-terminal β-sandwich (domain III) has not yet been clearly elucidated, although it has been also implicated in receptor recognition and specificity determination (for a review, see reference 1).

The binding of Cry toxins to their specific receptors in the larval midguts is one of the vital steps leading to Cry toxin activity. Numerous studies have proposed multiple Cry toxin receptors that mediate toxicity; these include cadherin-like proteins, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored aminopeptidase N (APN), GPI-anchored alkaline phosphatases (ALPs), and glycolipids (for a review, see reference 18). For instance, in our earlier studies, two different membrane-bound proteins, i.e., GPI-linked ALP (GPI-ALP) and GPI-linked APN (GPI-APN), have been identified as putative receptors mediating toxicity for the Cry4Ba toxin in the Aedes aegypti larvae (7, 19). Of particular interest, ALPs (EC 3.1.3.1; phosphomonoester hydrolases), ubiquitous enzymes widely found in microorganisms and animal kingdoms, are a highly conserved family of largely distributed cell surface and secreted metalloenzymes; many are GPI-anchored glycoproteins (for a review, see reference 13). To date, various ALPs from mosquitoes and other insect species have been reported as functional Cry toxin receptors, including Cry11Aa receptors from A. aegypti (8, 9), Cry11Ba receptors from A. aegypti (12) and Anopheles gambiae (10), a Cry1Ab receptor from Manduca sexta (3), and Cry1Ac receptors from Helicoverpa armigera (14) and Heliothis virescens (17).

Here, our research focused on the A. aegypti membrane-bound ALP (Aa-mALP) because it was initially cloned into Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells and apparently did not require protein glycosylation to be a functional receptor of the Cry4Ba toxin (7). Therefore, to determine whether a nonglycosylated Aa-mALP can retain the ability to bind its ligand Cry4Ba toxin, this receptor protein was heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli and then tested for its binding characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant plasmid expressing His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

A pair of specific primers (Sigma-Aldrich, Singapore) were used to amplify the cDNA coding sequence of Aedes aegypti membrane-bound ALP (Aa-mALP), which was previously isolated from the A. aegypti larval midgut (7). In this pair of primers, the forward primer was 5′-CCCCCCATATGCAAGGAGAATATGACCCAAAC-3′ (the NdeI recognition site is shown in boldface type, an added start codon is underlined, and the 5′-specific Aa-mALP sequence is shown in italic type), and the reverse primer was 5′-AAAAACTCGAGctaGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGTGCGCCTCCACACACGTC-3′ (the XhoI site is shown in boldface type, an additional stop codon is shown in small capital letters, six triplet codons encoding the six-His tag are underlined, and the 3′-specific Aa-mALP sequence is shown in italic type). The predicted secretion signal (36 amino acids from the N terminus) and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) attachment sequences (20 amino acids from the C terminus) were excluded as targets of PCR amplification. PCR was performed using high-fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs [NEB]). The 1.4-kb PCR product was double digested with NdeI and XhoI and then gel purified prior to ligation into the pET-17b expression vector, giving the pET-Aa-mALP plasmid. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS, and the gene segment was verified by DNA sequencing (Macrogen Inc., South Korea).

Expression of His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

E. coli harboring pET-Aa-mALP was grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml). When the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 to 0.5, protein expression was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 0.1 mM for 4 h and harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C). The expressed proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Western blot analysis was performed to confirm the His tag fusion by probing with alkaline phosphatase (ALP)-conjugated anti-His (C-terminal) antibody (Invitrogen), and the immunoreactive bands were subsequently visualized by using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) and nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) as a substrate.

Preparation and verification of refolded His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

Cells expressing the His tag-fused Aa-mALP protein as an inclusion body were disrupted by using a French pressure cell at 10,000 lb/in2, and the inclusion body was partially purified from crude lysate by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C).

For preparation of refolded Aa-mALP, the His tag-fused ALP inclusion bodies were solubilized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.5) containing 8 M urea (for 1 h at 25°C) and then refolded in a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity column (HisTrap HP column; GE Healthcare) by gradients of decreasing urea concentrations. The His tag-fused ALP was eluted from the column by 500 mM imidazole and desalted in 30-kDa-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) dialysis against carbonate buffer (50 mM Na2CO3/NaHCO3, pH 9.0).

The purified His tag-fused ALP protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and excised from the gel for subsequent verification by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) (Finnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer; Genome Institute, BIOTEC, Thailand).

Alkaline phosphatase activity assays of the purified His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

For colorimetric detection of ALP activity, the purified His tag-fused ALP protein was dotted onto the nitrocellulose membrane and subsequently assayed for its activity by the addition of ALP substrate solution (0.02% BCIP and 0.03% NBT in carbonate buffer [pH 9.0]). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 to 3 min; then, the filter was washed in distilled water and air dried.

The phosphatase activity assay via p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (New England BioLabs) was also performed. The hydrolysis of 5 mM pNPP to p-nitrophenol (pNP), a chromogenic product with absorbance at 405 nm) in ALP buffer (5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, and 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.5]) was measured, using a microplate spectrophotometer, for 5 min at 25°C. Specific activity was expressed as micromoles of pNP released per minute per milligram of protein.

Preparation of the Cry4Ba active toxin.

E. coli strain JM109 containing pMU388 plasmid encoding the 130-kDa Cry4Ba protoxin (2) was grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Protein expression and inclusion body preparation were performed similarly to His tag-fused Aa-mALP as mentioned above. Protein concentrations of the partially purified inclusion bodies were determined using the Bradford-based protein microassay (Bio-Rad), with bovine serum albumin fraction V (Sigma) as a standard protein. Toxin inclusion bodies were solubilized in carbonate buffer (50 mM Na2CO3/NaHCO3, pH 9.0) at a final concentration of 5 mg/ml for 1 h at 37°C. The solubilized toxin was activated by digesting with trypsin (tolylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin; Sigma) at a ratio of 1:20 (wt/wt) for the enzyme and toxin in the carbonate buffer (pH 9.0) for 16 h.

The 65-kDa activated toxin was further purified with a size exclusion fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (Superdex 200; Amersham Pharmacia Bioscience) and eluted with the carbonate buffer (pH 9.0) at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. The purified Cry4Ba protein fraction was then concentrated with a 30-kDa-MWCO Millipore (Amicon) membrane and further analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Dot blot-based binding assay.

The refolded Aa-mALP and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) (New England Biolab) were directly dotted onto nitrocellulose filters. The filters were blocked with PBS containing 5% skim milk (PBS-5% skim milk) at pH 7.5 for 1 h and then incubated with the activated Cry4Ba toxin (1.5 nM) in PBS-5% skim milk for 30 min. After the filters were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 three times for 15 min, they were incubated with mouse anti-Cry4Ba monoclonal antibody (1:2,000 dilution) in PBS-5% skim milk for 1 h. The immunocomplexes were subsequently detected with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Pierce, 1:5,000 dilution) followed by color development with hydrogen peroxide-3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Vector Lab).

Quantitative binding analysis via a QCM.

Twenty-seven-megahertz quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) sensor cells were prepared according to the instructions for the AFFINIXQ4 (Initium Inc., Japan) (for a review, see reference 16). The surface of the gold electrode was sequentially coated with a mixture of 0.01 mM dithiobis and 0.1 mM 3,3′-dithiopropionic acid for 10 min and then with 0.1 mM NiSO4 for 10 min. After rinsing with Milli-Q water, the sensor cells were added with 500 μl of 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) and then placed in cell holders. The His-tagged ALP was immobilized on the gold electrode at a final concentration of 0.3 nM via Ni2+-dithiobis (C2-NTA) linkage. The activated Cry4Ba protein was added to the sensor cells in stepwise increasing final concentrations of 30, 60, 90, and 120 nM, respectively. The dissociation constant (Kd) of the Cry4Ba toxin binding to the immobilized ALP was obtained from the plotted graph of the concentration of Cry4Ba and the concentration of Cry4Ba divided by ΔF, where ΔF is the measured frequency change (in hertz) in the QCM sensorgram as ascribed to the mass increase on the sensor surface.

To obtain the binding and dissociation rate constants (kon and koff, respectively), the Cry4Ba toxin was added to each sensor cell at different final concentrations, 15, 30, and 45 nM. A graph of Cry4Ba concentration and 1/relaxation time (τ−1) was plotted, and then kon and koff were determined from the slope and the y-axis intercept, respectively. Three independent experiments were performed to obtain the kinetic parameters.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Expression in E. coli and refolding of His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

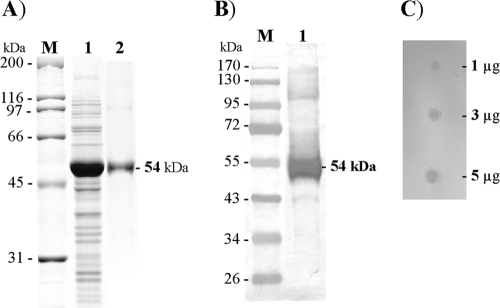

Recently, we have identified a GPI-anchored ALP as a functional midgut receptor of the B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis Cry4Ba toxin in A. aegypti larvae (7). In the present study, attempts were made to investigate further and gain insight into the binding characteristics of this Cry4Ba receptor. In this work, the Aa-mALP gene with an additional in-frame six-His codons at the 3′ end was amplified without the predicted secretion signal and GPI attachment sequences. It was highly expressed as an inclusion body by using the T7 promoter in E. coli cells upon IPTG induction. As predicted, SDS-PAGE analysis of the cell lysate showed a 54-kDa overexpressed protein (Fig. 1A, lane 1) that was verified by LC/MS/MS to be Aa-mALP, as it is the largest trypsin-generated peptide sequence (HYANAFNMAHMMVSEANTLLISMNDVGSTLSIPGYPARDTDILTEAGTSD KDSKPYLSLAYATGPSYDSYYQPNEGRVNPLAVLQGTP TQK) and perfectly matched the corresponding Aa-mALP sequence (residues His367-Lys457). Further analysis by Western blotting showed that this 54-kDa Aa-mALP protein strongly reacted with anti-His antibody (Fig. 1B, lane 1), confirming the presence of the His tag fusion in the expressed Aa-mALP. It is worth mentioning that there was no detectable signal at the 54-kDa band in a parallel Western blot experiment where the ALP-conjugated anti-His antibody was omitted (data not shown), implying that the denatured form of the 54-kDa Aa-mALP transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane cannot display ALP activity.

Fig. 1.

Detection and characterization of His tag-fused Aa-mALP expressed in E. coli. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis (Coomassie brilliant blue-stained 10% gel) of the expressed Aa-mALP protein. Lane M, broad-range protein markers; lane 1, protein expression pattern of IPTG-induced E. coli cells (∼107 cells) containing pET-Aa-mALP; lane 2, the His tag-fused Aa-mALP purified by elution through a HisTrap column. (B) Western blot analysis of His tag-fused Aa-mALP; lane M, prestained protein standard; lane 1, the purified His tag-fused Aa-mALP protein detected with anti-His (C-terminal) antibody. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of the gels in panels A and B. (C) Phosphatase activity assay via BCIP/NBT qualitative dot blotting of 1, 3, and 5 μg of the purified His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

For preparation of refolded Aa-mALP, the His tag-fused insoluble inclusion body was completely dissolved in 8 M urea at 25°C for 1 h. The solubilized His tag-fused protein was refolded in a Ni-NTA affinity column via gradients of decreasing urea concentrations, and finally the refolded protein was obtained in urea-imidazole-free carbonate buffer (pH 9.0) with ≥95% purity as analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 2). It should be noted that a high proportion of the refolded ALP monomeric form rather than aggregated multimers was recovered, since a single major peak at an elution volume corresponding to an ∼50-kDa monomer was observed by size exclusion chromatography (data not shown).

Enzymatic activity of the purified His tag-fused Aa-mALP.

ALP activity of the purified refolded ALP was at first evident by qualitative dot blotting using insoluble chromogenic substrates (BCIP/NBT) (Fig. 1C). To further quantify the specific ALP activity of the purified protein, we also performed a phosphatase activity assay. It was observed that the purified refolded ALP exhibited an apparent specific activity of 0.30 ± 0.02 μmol/min/mg toward the cleavage of the small organic phosphate pNPP, albeit at lower activity compared to the Aa-mALP expressed in Sf9 cells (0.85 ± 0.08 μmol/min/mg [7]). However, the results of our study are not consistent with the results of another study of the lepidopteran-specific Cry1Ac-binding ALPs from Heliothis virescens; in that study, the E. coli-expressed ALP clones showed no detectable enzymatic activity toward BCIP/NBT substrates (17). The authors suggested that the loss of phosphatase activity of the expressed ALPs is due to their misfolding or posttranslational modifications (17), although it remains to be clearly elucidated whether the denaturing conditions performed on SDS-PAGE abolished the cloned ALP activity or whether additional refolding steps are needed.

Binding affinity and kinetics of immobilized Aa-mALP with Cry4Ba toxin.

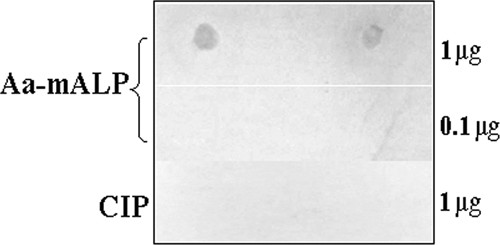

To determine the binding ability of the purified refolded Aa-mALP with the activated Cry4Ba toxin, a dot blot-based binding assay was initially performed. The results of this assay revealed that this refolded receptor immobilized on the nitrocellulose filter was able to bind its counterpart toxin, whereas no binding signal was detected between calf intestinal ALP (as a control) and the Cry4Ba toxin (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Dot blot-based analysis of binding between Aa-mALP and the Cry4Ba toxin. The purified refolded Aa-mALP (0.1 or 1 μg) and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) (1 μg) were spotted in duplicate on nitrocellulose membranes which were then incubated with the activated Cry4Ba toxin (1.5 nM). The binding signals were detected as described in Materials and Methods.

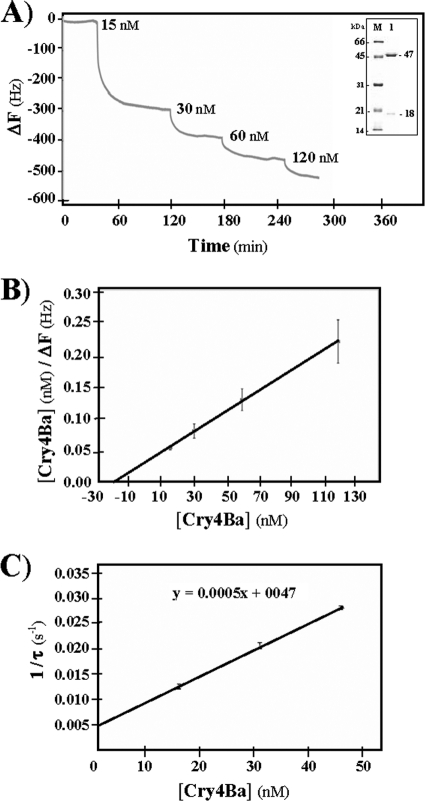

Further attempts were made to assess the binding characteristics of the His tag-fused Aa-mALP with the Cry4Ba toxin by using the quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) technique. After 0.3 nM Aa-mALP was injected into the QCM sensor cell, a frequency decrease of 160 ± 2 Hz was observed in a binding sensorgram. This frequency decrease can be ascribed to the mass increase on the sensor surface of 99.2 ± 1.2 ng (1.9 ± 0.01 pmol)/cm2. When different amounts of the activated Cry4Ba toxin (final concentrations of 30, 60, 90, and 120 nM) were sequentially injected into sensor cells covered with the His tag-fused Aa-mALP protein, frequency decreases of 307 ± 11, 401 ± 15, 480 ± 16, and 532 ± 15 Hz were observed, respectively (Fig. 3A). The frequency decrease for the saturation binding of Cry4Ba corresponds to the mass increase of 330 ± 9 ng (5.0 ± 0.01 pmol)/cm2. As a result, approximately two Cry4Ba molecules are bound to one His tag-fused Aa-mALP immobilized on the surface (1.9 ± 0.01 pmol/cm2). Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that basically two binding sites may possibly be available in Aa-mALP for this toxin. Recently, at least two distinct binding sites for the Cry11Aa toxin have been mapped in another A. aegypti ALP isoform (ALP1) which was also shown to bind Cry4Ba to a lower extent (8). However, at this time, it is still not clear how this ALP isoform could in reality serve as a functional midgut receptor of Cry11Aa (8) or Cry11Ba (12) in the A. aegypti larvae, since there are no data to directly support this identified isoform as a membrane-bound ALP (7) or as the same GPI-linked ALP that was characterized earlier by the authors (9).

Fig. 3.

(A) Normalized changes in resonant frequency upon addition of the purified activated Cry4Ba toxin onto the QCM sensor cell precoated with the His tag-fused Aa-mALP. (Inset) Cry4Ba toxin after trypsin activation showing 47- and 18-kDa trypsin-resistant fragments (lane 1). The gel is as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (B) Linear regression plot of the concentration of Cry4Ba and the concentration of Cry4Ba divided by ΔF. The x-axis intercept is −Kd. (C) Linear regression plot of the concentration of Cry4Ba and 1/relaxation time (τ−1). The y-axis intercept is koff, and the slope of the line is kon. Values in panels B and C are the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM; error bars) for three replicate tests.

In addition, the dissociation constant (Kd) of the Cry4Ba binding to the immobilized Aa-mALP was found to be ∼14 nM (determined as the x-axis intercept of the linear regression line [Fig. 3B]), indicating that the Cry4Ba toxin binds to its ALP receptor with high affinity. However, this Kd value for the interaction between Cry4Ba and the purified immobilized purified Aa-mALP is not similar to that (Kd of ∼520 nM) reported previously between Cry4Ba and the A. aegypti midgut brush-border membrane (BBM) fraction measured using homologous competition assays (6). The discrepancy between these two apparent Kd values could imply a small fraction of the Cry4Ba receptor population in their BBM preparation. Nevertheless, our apparent binding affinity value is approximately 2 times higher than that (Kd, ∼24 nM) between Cry11Ba and Ag-ALP1t (a truncated 57-kDa E. coli-expressed Anopheles gambiae ALP isoform) as determined by a microplate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, while no competition for binding to this Ag-ALP was observed between 125I-labeled Cry11Ba and Cry4Ba (10).

The kinetics of Cry4Ba binding to this high-affinity receptor have also been evaluated. When the relaxation time of binding (τ) was obtained at different concentrations of the Cry4Ba toxin, the binding rate constant (kon, the second-order rate constant) and the dissociation rate constant (koff, the first-order rate constant) were determined from the linear regression line (Fig. 3C) to be approximately 5.0 × 105 M−1 s−1 and 5.0 × 10−3 M−1 s−1, respectively (the average of three independent experiments). These kinetic parameters give the calculated Kd (Kd = koff/kon) of ∼10 nM, which is comparable to the Kd (∼14 nM) obtained above from the saturation binding curve, indicating that this binding interaction with significant orientation effects (as kon < 108 M−1 s−1) basically follows a simple mass action kinetic model (11).

It is interesting to note that the E. coli-expressed Aa-mALP still retains high-affinity binding for the Cry4Ba toxin only under physiological conditions demonstrated here via QCM and also on dot blots. However, this toxin binding was not observed by ligand blot analysis in a toxin overlay assay (data not shown), suggesting that the polypeptide portion of this receptor is the binding determinant for the toxin, as the SDS-PAGE conditions used in the assay might have irreversibly denatured the binding site(s) on the ALP protein. This has strengthened our previous notion that a sugar moiety is not required for toxin binding, as the mALP protein expressed in E. coli cells is least likely to be glycosylated, although it has now become evident that bacteria possess both protein N- and O-glycosylation pathways (15). Our data are in agreement with the results of Hua et al. (10), which also suggested that an E. coli-expressed Anopheles gambiae ALP isoform (Ag-ALP1t) is not glycosylated and thus, that its counterpart toxin, Cry11Ba, was supposed to recognize the polypeptide part rather than a saccharide portion. However, these findings are inconsistent with the binding of the lepidopteran-specific Cry1Ac toxin to ALPs from Helicoverpa armigera and Heliothis virescens larvae where N-acetylgalactosamine on the receptor is essential for toxin binding (14, 17).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from BIOTEC and the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) in cooperation with the Commission of Higher Education (CHE). Scholarships from TRF-RGJ (to A.T.) and CHE (to M.D.) are gratefully acknowledged.

We are indebted to Yoshio Okahata (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan) for making facilities available for QCM studies.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Angsuthanasombat C. 2010. Structural basis of pore formation by mosquito-larvicidal proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis. Open Toxinol. J. 3:119–125 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angsuthanasombat C., et al. 1987. Cloning and expression of 130-kd mosquito-larvicidal δ-endotoxin gene of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 208:384–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arenas I., Bravo A., Soberón M., Gómez I. 2010. Role of alkaline phosphatase from Manduca sexta in the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ab toxin. J. Biol. Chem. 285:12497–12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker N., Margalit J. 1993. Use of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis against mosquitoes and blackflies, p. 147–170 In Entwistle P. F., Cory J. S., Bailey M. J., Higgs S. (ed.), Bacillus thuringiensis, an environmental biopesticide: theory and practice. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boonserm P., Davis P., Ellar D. J., Li J. 2005. Crystal structure of the mosquito-larvicidal toxin Cry4Ba and its biological implications. J. Mol. Biol. 348:363–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Barros Moreira Beltrao H., Silva-Filha M. H. 2007. Interaction of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis Cry toxins with binding sites from Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae midgut. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266:163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dechklar M., Tiewsiri K., Angsuthanasombat C., Pootanakit K. 2011. Functional expression in insect cells of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked alkaline phosphatase from Aedes aegypti larval midgut: a Bacillus thuringiensis Cry4Ba toxin receptor. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernández L. E., et al. 2009. Cloning and epitope mapping of Cry11Aa-binding sites in the Cry11Aa-receptor alkaline phosphatase from Aedes aegypti. Biochemistry 48:8899–8907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernández L. E., Aimanova K. G., Gill S. S., Bravo A., Soberón M. 2006. A GPI-anchored alkaline phosphatase is a functional midgut receptor of Cry11Aa toxin in Aedes aegypti larvae. Biochem. J. 394:77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hua G., Zhang R., Bayyareddy K., Adang M. J. 2009. Anopheles gambiae alkaline phosphatase is a functional receptor of Bacillus thuringiensis jegathesan Cry11Ba toxin. Biochemistry 48:9785–9793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jakubowski H. 2002. Understanding biochemical dissociation constants: a temporal perspective. J. Chem. Educ. 79:968–971 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Likitvivatanavong S., Chen J., Bravo A., Soberón M., Gill S. S. 2011. Cadherin, alkaline phosphatase, and aminopeptidase N as receptors of Cry11Ba toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. jegathesan in Aedes aegypti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:24–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Millán J. L. 2006. Alkaline phosphatase: structure, substrate specificity and functional relatedness to other members of a large superfamily of enzymes. Purinergic Signal. 2:335–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ning C., et al. 2010. Characterization of a Cry1Ac toxin-binding alkaline phosphatase in the midgut from Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 56:666–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nothaft H., Szymanski C. M. 2010. Protein glycosylation in bacteria: sweeter than ever. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:765–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okahata Y., Niikura K., Furusawa H., Matsuno H. 2000. A highly sensitive 27 MHz quartz-crystal microbalance as a device for kinetic measurements of molecular recognition on DNA strands. Anal. Sci. 16:1113–1119 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perera O. P., Willis J. D., Adang M. J., Jurat-Fuentes J. L. 2009. Cloning and characterization of the Cry1Ac-binding alkaline phosphatase (HvALP) from Heliothis virescens. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39:294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pigott C. R., Ellar D. J. 2007. Role of receptors in Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:255–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saengwiman S., et al. 2011. In vivo identification of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry4Ba toxin receptors by RNA interference knockdown of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked aminopeptidase N transcripts in Aedes aegypti larvae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407:708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]