Abstract

Two new primer sets of a 766- and a 344-bp fragment were introduced into the conventional Bruce-ladder PCR assay. This novel multiplex PCR assay rapidly and concisely discriminates Brucella canis and Brucella microti from Brucella suis strains and also may differentiate all of the 10 Brucella species.

TEXT

The alphaproteobacterial genus Brucella consists of 10 species: B. abortus, B. canis, B. suis, B. ovis, B. neotomae, B. melitensis, B. ceti, B. pinnipedialis, B. microti, and B. inopinata (3, 5, 16, 17). Brucella species show a host preference, but some strains can be transmitted among a variety of animals, including humans (11, 12, 14, 18).

To accelerate effective prevention and control of brucellosis, a fast and accurate identification method is necessary. Many studies have developed PCR-based assays for the discrimination of Brucella species (2, 4, 7, 8, 10). Recently, López-Goñi et al. reported that the Bruce-ladder PCR assay could differentiate most Brucella species, including marine mammal and vaccine strains B. abortus S19, B. abortus RB51, and B. melitensis Rev.1 (6, 10, 13). However, these assays did not solve the problem of erroneous identification of B. canis isolates (such as B. suis) and basic differentiation between two marine mammal Brucella species (B. ceti and B. pinnipedialis) (9, 13, 15). Therefore, the aim of this study was to develop a fast, simple, and accurate one-step multiplex PCR assay to differentiate 10 Brucella species using 22 reference strains and 106 field isolates in South Korea.

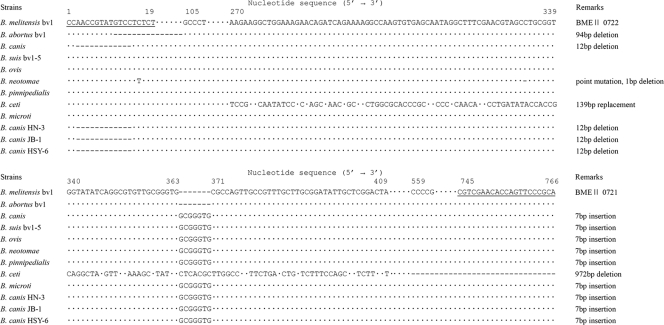

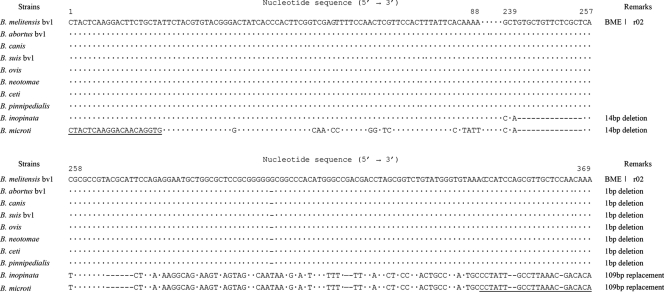

To discriminate between B. canis and B. suis, alignments of their whole-genome sequence or each biovar short-gun sequence were performed extensively using CLC Main Workbench (version 5.7) software (Insilicogen Inc., South Korea). Compared to five biovars of B. suis, a specific 12-bp deleted genetic site was discovered in the BME2 0722 genetic region of B. canis (Fig. 1). Other Brucella strains, except for B. abortus, did not show this gene deletion. However, in B. abortus, a 94-bp gene deletion that partially consisted of the 12-bp deleted site was detected. The reverse primer site confirmed an extensive 972-bp gene deletion site at BME2 0721 in B. ceti. This deletion site was not found in other Brucella species such as B. pinnipedialis. Based on the results from the alignment, a new primer set of 766 bp was designed to replace the 794-bp fragment of the BME2 436f-435r primer set in the Bruce-ladder PCR assay (10). This new primer set consisted of 5′-CCAACCGTATGTCCTCTCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCGGGAACTGGTGTTCGACG-3′ (reverse). Another primer set designed from the BME1 r02 region, which was aligned with 23S rRNA sequences from other Brucella species, was also included for the detection of B. microti (Fig. 2). The forward primer was designed by a site genetically mutated compared to other Brucella species, and the reverse primer was designed at a 109-bp replacement genetic site of the BME1 r02 region. A distinctive sequence site of 344 bp in B. microti was recognized using the primer set 5′-CTACTCAAGGACAACAGGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTGTCGTTTAAGGCAATAGG-3′ (reverse). Seven primer sets, except for BME2 436f-435r primer, were synthesized in accordance with the Bruce-ladder assay as described previously (10). PCR amplification was performed using 2× PCR premix kit (Cosmo Genetech, South Korea). PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturing at 95°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min.

Fig. 1.

Alignment for specific gene fragments (766 bp) of representative B. canis isolates and Brucella reference strains. The B. canis isolates are indicated as HN-3, JB-1, and HSY-6. The primer set is underlined. Dots indicate consensus sequence; dashes indicate deletions.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of specific gene fragment (344 bp) of B. microti compared to other Brucella species. The primer set is underlined. Dots indicate consensus sequence; dashes indicate deletions.

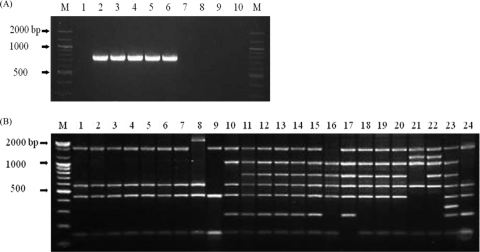

As a result, the PCR using the new primer set of 766 bp distinctly discriminated B. canis and B. suis strains (Fig. 3A). In a multiplex PCR assay including this primer set, B. melitensis (3 biovars), B. suis (5 biovars), B. ovis, B. neotomae, B. pininipedialis, and B. microti were amplified selectively, whereas B. abortus (biovars 1 to 6 and 9, RB51, and S19), B. canis, B. ceti, and B. inopinata reference strains did not generate any amplicons (Fig. 3B). Also, 76 B. canis strains used in this study unambiguously showed as not being amplified by this specific primer set (data not shown). Therefore, the primer set of the 794-bp fragment in the Bruce-ladder PCR assay was replaced by our novel primer set of 766 bp, which can distinguish B. canis from B. suis strains and could discriminate between B. ceti and B. pinnipedialis reference strains (Fig. 3b). This novel primer might be used to differentiate between B. ceti and B. pinnipedialis even though it was not applied to marine mammal Brucella isolates.

Fig. 3.

(A) PCR products of B. canis and B. suis strains amplified using the novel primer set of 766 bp. Lanes M, 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 1, B. canis ATCC 23365; lanes 2 to 6, B. suis biovars 1 to 5, respectively; lanes 7 to 10, B. canis isolates. (B) PCR products from Brucella species amplified using the advanced multiplex PCR assay. Lane M, 100-bp DNA ladder; lanes 1 to 7, B. abortus biovars 1 to 6 and 9, respectively; lane 8, B. abortus RB51; lane 9, B. abortus S19; lane 10, B. canis ATCC 23365; lanes 11 to 15, B. suis biovars 1 to 5; lane 16, B. ovis; lane 17, B. neotomae; lanes 18 to 20, B. melitensis biovars 1 to 3; lane 21, B. ceti; lane 22, B. pinnipedialis; lane 23, B. microti; lane 24, B. inopinata.

Audic et al. analyzed the whole-genome sequence of B. microti and reported that the most noticeable difference between B. microti and other Brucella species was in the 23S rRNA gene (1). Based on this report, a new designed primer set of a 344-bp fragment specifically amplified only B. microti; however, it did not detect other Brucella species and 106 field isolates used this study (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the recent B. inopinata strain was distinguished from other Brucella species because of not being amplified by the two new primers as it was by the previously described primer sets (1,071 bp) (13).

Consequently, the novel multiplex PCR assay was a rapid and robust diagnostic method to discriminate B. canis and B. microti from other Brucella species, including B. suis, in a single step. Moreover, this assay discriminated all 10 Brucella species, including marine mammalian reference strains. This multiplex PCR assay could be readily utilized as a genetic screening tool for Brucella strains isolated from animals and humans, not only for the prevention and control of the disease but also in any microbiology laboratory worldwide. In addition, this assay could contribute to efforts to eradicate brucellosis in underdeveloped or developing countries with limited financial resources.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a fund of the Veterinary Science Technical Development project of the National Veterinary Research and Quarantine Service, South Korea (project no. C-AD13-2010-12-01).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Audic S., Lescot M., Claverie J. M., Scholz H. C. 2009. Brucella microti: the genome sequence of an emerging pathogen. BMC Genomics 10: 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bricker B. J., Halling S. M. 1994. Differentiation of Brucella abortus bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis bv. 1 by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32: 2660–2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corbel M. J. 1997. Brucellosis: an overview. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3: 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ewalt D. R., Bricker B. J. 2000. Validation of the abbreviated Brucella AMOS PCR as a rapid screening method for differentiation of Brucella abortus field strain isolates and the vaccine strains, 19 and RB51. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38: 3085–3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster G., Osterman B. S., Godfroid J., Jacques I., Cloeckaert A. 2007. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57: 2688–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. García-Yoldi D., et al. 2006. Multiplex PCR assay for the identification and differentiation of all Brucella species and the vaccine strains Brucella abortus S19 and RB51. Clin. Chem. 52: 779–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gopaul K. K., Koylass M. S., Smith C. J., Whatmore A. M. 2008. Rapid identification of Brucella isolates to the species level by real time PCR based single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis. BMC Microbiol. 8: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herman L., De Ridder H. 1992. Identification of Brucella spp. by using the PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58: 2099–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koylass M. S., et al. 2010. Comparative performance of SNP typing and ‘Bruce-ladder’ in the discrimination of Brucella suis and Brucella canis. Vet. Microbiol. 19: 450–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. López-Goñi I., et al. 2008. Evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay (Bruce-ladder) for molecular typing of all Brucella species, including the vaccine strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46: 3484–3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lucero N. E., et al. 2005. Unusual clinical presentation of brucellosis caused by Brucella canis. J. Med. Microbiol. 54: 505–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maquart M., Zygmunt M. S., Cloeckaert A. 2009. Marine mammal Brucella isolates with different genomic characteristics display a differential response when infecting human macrophages in culture. Microbes Infect. 11: 361–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayer-Scholl A., Draeger A., Göllner C., Scholz H. C., Nöckler K. 2010. Advancement of a multiplex PCR for the differentiation of all currently described Brucella species. J. Microbiol. Methods 80: 112–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno E., Cloeckaert A., Moriyón I. 2002. Brucella evolution and taxonomy. Vet. Microbiol. 90: 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Office International des Épizooties 2008. Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals, 6th ed. Office International des Épizooties, Paris, France [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scholz H. C., et al. 2010. Brucella inopinata sp. nov., isolated from a breast implant infection. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60: 801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scholz H. C., et al. 2008. Brucella microti sp. nov., isolated from the common vole Microtus arvalis. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58: 375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seleem M. N., Boyle S. M., Sriranganathan N. 2010. Brucellosis: a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet. Microbiol. 140: 392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]