Abstract

Although many assume that measurement of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using a marker such as iothalamate (iGFR) is superior to equation-estimated GFR (eGFR), each of these methods has distinct disadvantages. Because physicians often use renal function to guide the screening for various CKD-associated complications, one method to compare the clinical utility of iGFR and eGFR is to determine the strength of their association with CKD-associated comorbidities. Using a subset of 1214 participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, we determined the cross-sectional associations between known complications of CKD and iGFR, eGFR estimated from serum creatinine (eGFR_Cr), and eGFR estimated from cystatin C (eGFR_cysC). We found that none of the measures of renal function strongly associated with CKD complications and that the relative strengths of associations varied according to the outcome of interest. For example, iGFR demonstrated better discrimination than eGFR_Cr and eGFR_cysC for outcomes of anemia and hemoglobin concentration; however, both eGFR_Cr and eGFR_cysC demonstrated better discrimination than iGFR for outcomes of hyperphosphatemia and phosphorus level. iGFR and eGFR had similar strengths of association with hyperkalemia/potassium level and with metabolic acidosis/bicarbonate level. In conclusion, iothalamate measurement of GFR is not consistently superior to equation-based estimations of GFR in explaining CKD-related comorbidities. These results raise questions regarding the conventional view that iGFR is the “gold standard” measure of kidney function.

Kidney function is multifaceted, spanning clearance (via both filtration and secretion) as well as hormonal (e.g., production of erythropoietin) and metabolic (e.g., participation in gluconeogenesis) functions. But most quantifications of kidney function have focused on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as decrements in GFR largely (although imperfectly) correlate with deteriorations in the hormonal, metabolic and other functions of the kidney. It is widely assumed that the measured GFR using a filtration marker such as iothalamate (iGFR) provides the best assessment of renal function and is superior to equation-estimated GFR (eGFR).1 iGFR has therefore been measured in numerous high-profile randomized clinical trials and observational studies,2–4 although this method is costly and imposes a significant burden on study participants.

The disadvantages of serum-creatinine-based estimations of GFR are well known and include nonfiltration clearance of creatinine and confounding by differences in rates of creatinine production. It is now appreciated that there are also numerous nonkidney function determinants of serum cystatin C level. But there are several disadvantages to iGFR measurements as well. This technique usually measures renal function over a relatively short duration of time—typically several hours. There is also known diurnal variation in GFR among both normal individuals5 and those with parenchymal kidney disease.6 In addition, GFR changes with posture and acute changes in diet.7,8 Estimates of renal function using endogenous filtration markers such as creatinine may provide a better measure of average renal function over a period of days to weeks, which is conceptually the underlying physiologic parameter of interest.9 Finally, iGFR is subject to unique sources of measurement errors, such as the timed collection of urine and blood samples. In other words, iGFR and eGFR may have different sources of bias.

We evaluated the performance of iGFR versus eGFR as a measure of renal function by determining whether, compared with eGFR, iGFR was more strongly associated with well-known sequelae of chronic renal insufficiency.

RESULTS

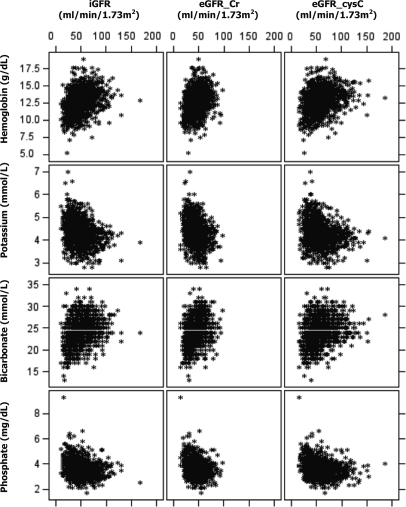

Baseline characteristics of the 1214 participants are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows, graphically, the association (scatterplot) between different measures of renal function and the four outcomes of interest. Although eGFR_Cr was constrained by study design, some enrollees had baseline eGFR_Cr values higher than their screening/entry eGFR_Cr values. A few CRIC participants had much higher baseline iGFR or eGFR_cysC values. As expected, in this cross-sectional analysis, CRIC participants with worse renal function in general had lower levels of hemoglobin and bicarbonate, and higher levels of potassium and phosphorus, and were more likely to suffer anemia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia (Table 3). However, as the scatterplots illustrate, at any level of measured or estimated GFR, there was a wide variation in the levels of hemoglobin, potassium, bicarbonate, and phosphorus.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study population (n = 1214) at baseline

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD or number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 56 ± 13 |

| Women | 535 (44%) |

| Caucasians/African Americans | 604 (50%)/498 (41%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 558 (46%) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.68 ± 0.57 |

| Cystatin C, mg/L | 1.43 ± 0.51 |

| iGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 49.2 ± 20.2 |

| eGFR_Cr, ml/min/1.73m2 | 45.2 ± 14.1 |

| eGFR_Cys, ml/min/1.73m2 | 56.9 ± 22.9 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/dl | 12.7 ± 1.7 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin <13 g/dl in men and <12 g/dl in women), n (%) | 566 (47%) |

| Potassium level, mmol/L | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| Hyperkalemia (potassium >5.3 mmol/L), n (%) | 44 (3.6%) |

| Bicarbonate level, mmol/L | 24 ± 3 |

| Metabolic acidosis (bicarbonate <22 mmol/L), n (%) | 214 (18%) |

| Phosphate level, mg/dl | 3.7 ± 0.7 |

| Hyperphosphatemia (phosphate >5 mg/dl), n (%) | 36 (3.0%) |

Figure 1.

Scatterplot showing levels of hemoglobin, potassium, bicarbonate, and phosphate versus GFR directly measured using urinary clearance of iothalamate (iGFR), serum creatinine estimated GFR (eGFR_Cr), and serum cystatin C estimated GFR (eGFR_cysC).

Table 3.

Associations between three measures of renal function and four outcomes: Bivariable linear and logistic regression results

| Odds Ratio (95% CI; per 10 ml/min/1.73m2 decrease) | P-value | C-statistic | Change in Level (95% CI; per 10 ml/min/1.73m2 decrease) | P-value | R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | Hemoglobin level (g/dl) | ||||||

| iGFR | 1.53 (1.43, 1.65) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | iGFR | −0.31 (−0.27, −0.36) | <0.0001 | 0.13 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.57 (1.43, 1.72) | <0.0001 | 0.67 | eGFR_Cr | −0.38 (−0.31, −0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.43 (1.34, 1.52) | <0.0001 | 0.70 | eGFR_cysC | −0.26 (−0.22, −0.30) | <0.0001 | 0.11 |

| iGFR | 1.59 (1.41, 1.79) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | iGFR | −0.30 (−0.22, −0.38) | <0.0001 | 0.13 |

| eGFR_Cr | 0.94 (0.81, 1.10) | 0.45 | eGFR_Cr | −0.03 (0.09, −0.14) | 0.65 | ||

| iGFR | 1.35 (1.20, 1.53) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | iGFR | −0.24 (−0.16, −0.33) | <0.0001 | 0.14 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.14 (1.03, 1.27) | 0.01 | eGFR_cysC | −0.08 (−0.00, −0.15) | 0.0497 | ||

| Hyperkalemia | Potassium level (mmol/L) | ||||||

| iGFR | 1.67 (1.35, 2.07) | <0.0001 | 0.73 | iGFR | 0.08 (0.06, 0.09) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.86 (1.43, 2.42) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | eGFR_Cr | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.58 (1.29, 1.94) | <0.0001 | 0.72 | eGFR_cysC | 0.06 (0.05, 0.08) | <0.0001 | 0.07 |

| iGFR | 1.45 (1.03, 2.06) | 0.04 | 0.73 | iGFR | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | 0.0002 | 0.09 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.25 (0.81, 1.93) | 0.32 | eGFR_Cr | 0.05 (0.02, 0.09) | 0.005 | ||

| iGFR | 1.39 (0.97, 2.00) | 0.07 | 0.73 | iGFR | 0.05 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.0002 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.22 (0.88, 1.71) | 0.24 | eGFR_cysC | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) | 0.04 | ||

| Metabolic Acidosis | Bicarbonate level (mmol/L) | ||||||

| iGFR | 1.65 (1.49, 1.83) | <0.0001 | 0.73 | iGFR | −0.43 (−0.35, −0.51) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.92 (1.68, 2.19) | <0.0001 | 0.73 | eGFR_Cr | −0.65 (−0.53, −0.76) | <0.0001 | 0.09 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.62 (1.46, 1.79) | <0.0001 | 0.73 | eGFR_cysC | −0.37 (−0.29, −0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| iGFR | 1.36 (1.15, 1.60) | 0.0003 | 0.74 | iGFR | −0.18 (−0.04, −0.32) | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71) | 0.004 | eGFR_Cr | −0.44 (−0.24, −0.64) | <0.0001 | ||

| iGFR | 1.27 (1.07, 1.51) | 0.006 | 0.74 | iGFR | −0.27 (−0.12, −0.43) | 0.0004 | 0.09 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.34 (1.14, 1.58) | 0.0004 | eGFR_cysC | −0.16 (−0.02, −0.29) | 0.02 | ||

| Hyperphosphatemia | Phosphate level (mg/dl) | ||||||

| iGFR | 1.45 (1.17, 1.79) | 0.0007 | 0.69 | iGFR | 0.09 (0.07, 0.10) | <0.0001 | 0.07 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.81 (1.36, 2.42) | <0.0001 | 0.71 | eGFR_Cr | 0.13 (0.11, 0.16) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.53 (1.23, 1.90) | 0.0001 | 0.72 | eGFR_cysC | 0.08 (0.07, 0.10) | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| iGFR | 1.02 (0.71, 1.46) | 0.92 | 0.71 | iGFR | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_Cr | 1.77 (1.08, 2.93) | 0.02 | eGFR_Cr | 0.09 (0.05, 0.14) | <0.0001 | ||

| iGFR | 0.99 (0.69, 1.42) | 0.96 | 0.72 | iGFR | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.06) | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| eGFR_cysC | 1.54 (1.07, 2.21) | 0.02 | eGFR_cysC | 0.06 (0.03, 0.09) | <0.0001 | ||

Results of linear regression and logistic regression are shown in Table 2. None of the measures of renal function were strongly associated with complications of renal insufficiency, as most of the R2 values were around 0.10. We found that the relative strengths of the associations varied according to the outcome examined. For example, when examining the outcomes of anemia and hemoglobin concentration, the C-statistic and R2 were larger for iGFR than eGFR_Cr or eGFR_cysC (C-statistic 0.72 versus 0.67 and 0.70, respectively; R2 0.13 versus 0.09 and 0.11, respectively). But when examining the outcomes of hyperphosphatemia and phosphorus level, the C-statistic and R2 were smaller for iGFR than eGFR_Cr or eGFR_cysC (C-statistic 0.69 versus 0.71 and 0.72, respectively; R2 0.07 versus 0.08 and 0.08, respectively). iGFR and eGFR has similar strengths of association with hyperkalemia/potassium level and with metabolic acidosis/bicarbonate level.

Table 2.

Associations between three measures of renal function and four outcomes: Univariable linear and logistic regression results

| Outcome | Measure of renal function | C-statistic | Outcome | Measure of renal function | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | iGFR | 0.72 | Hemoglobin level | iGFR | 0.13 |

| eGFR_Cr | 0.67 | eGFR_Cr | 0.09 | ||

| eGFR_cysC | 0.70 | eGFR_cysC | 0.11 | ||

| Hyperkalemia | iGFR | 0.73 | Potassium level | iGFR | 0.08 |

| eGFR_Cr | 0.72 | eGFR_Cr | 0.08 | ||

| eGFR_cysC | 0.72 | eGFR_cysC | 0.07 | ||

| Metabolic acidosis | iGFR | 0.73 | Bicarbonate level | iGFR | 0.08 |

| eGFR_Cr | 0.73 | eGFR_Cr | 0.09 | ||

| eGFR_cysC | 0.74 | eGFR_cysC | 0.08 | ||

| Hyperphosphatemia | iGFR | 0.69 | Phosphate level | iGFR | 0.07 |

| eGFR_Cr | 0.71 | eGFR_Cr | 0.08 | ||

| eGFR_cysC | 0.72 | eGFR_cysC | 0.08 |

In sensitivity analyses, the relationships noted above were very similar when the scale of GFR measures were changed to standard deviation (SD) units rather than per change in 10 ml/min/1.73m2 on their natural scales (data not shown). Results were also similar when all iGFR periods were included in the analysis (data not shown).

Results were unchanged when we excluded patients who were on erythropoiesis stimulating agents (3% of the cohort); patients on sodium polystyrene sulfonate (0.6% of the cohort); patients on alkali therapy (2% of the cohort); patients on phosphorus binders (6% of the cohort). Diabetes status did not consistently modify the relationships between eGFR or iGFR and comorbidities related to renal insufficiency. When we examined subgroups defined by age (above or below 60 yr), sex, race (African American versus non-African American), or iGFR (above or below 45 ml/min/1.73m2), in no subgroup was iGFR consistently superior to eGFR_Cr or eGFR_cysC. Similar results were seen after adjustment for age, sex, and race. Results were unchanged when the CKD-EPI equation was used instead of the MDRD equation to estimate eGFR_Cr (data not shown).

The results of the bivariable analyses were also consistent (Table 3). For example, in the case of anemia or hemoglobin level, eGFR_Cr contributed no further information once iGFR was known (P = 0.45 and 0.65, respectively). In contrast, for hyperphosphatemia or phosphorus level, iGFR was no longer independently associated with outcome once eGFR_cysC was known (P = 0.96 and 0.10, respectively). Models examining hyperkalemia/potassium level and metabolic acidosis/bicarbonate level gave results that were intermediate.

DISCUSSION

It is widely assumed that measured GFR using a filtration marker such as iothalamate (iGFR) provides the best measurement of renal function and is superior to creatinine-based or cystatin-based equation-estimated GFR (eGFR). However, few studies have tested this assumption. In fact, it can be argued that this assertion is a tautology, since many investigators define directly measured GFR as the “gold standard” measurement of renal function.

The principal clinical purpose of assessing a patient's renal function is to anticipate complications, enabling better screening and treatment decisions. Determining with great accuracy a certain physiologic parameter—actual GFR—is a clinically less important goal. Measurement of iGFR is more cumbersome and invasive than measurements of eGFR. But this may be worthwhile if iGFR were more strongly and consistently associated with known sequelae of chronic kidney disease (CKD), such as anemia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia. Finding that iGFR is more strongly and consistently associated with these known sequelae of CKD would provide empiric evidence to support the commonly held belief that it is a better measure of renal function than eGFR.

The key finding of this study is that iGFR was not consistently superior to either measure of eGFR in explaining comorbidities related to renal insufficiency. Another finding was that iGFR explained a relatively small proportion the observed variation in severity of CKD sequelae (e.g., on the order of only 10% since correlations were approximately 0.1). We are not able to determine the exact reason for the relatively disappointing performance of iGFR. One possibility may be that measurement errors associated with iGFR are greater than generally appreciated.

There have been few prior rigorous examinations of the relative performance of iGFR versus eGFR addressing their associations with adverse consequences of CKD. Menon et al. analyzed the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease trial data and compared the strengths of association between four measures of renal function: 1/serum creatinine, 1/serum cystatin C, MDRD equation eGFR, and measured iGFR and four outcomes: all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, kidney failure, and a composite outcome of kidney failure and all-cause mortality. They found that iGFR was not the strongest predictor in any of the four outcomes. For example, in adjusted models for cardiovascular disease mortality, the hazard ratio (per 1 SD decrease) for iGFR was 1.28 but was 1.64 for 1/cystatin C. In adjusted models for kidney failure, the hazard ratio for iGFR was 2.41 compared with 2.81 for 1/creatinine.10 Although it can be argued that clinicians use serum creatinine, in part, to determine when to initiate maintenance renal replacement therapy (the operational definition of “kidney failure”), and cystatin C may be independently associated with cardiovascular disease as a reflection of inflammation11,12 (and not GFR), these results are consistent with our analysis of outcomes that are more immediate consequences of CKD. Moranne et al. studied 1030 adult patients from a hospital-based cohort with CKD stages 2 through 5 who had GFR directly measured using urinary clearance of injected 51Cr-EDTA as well as estimated using the MDRD equation. Although comparing these two measures of GFR was not the focus of that study, there was no evidence from the data presented that measured GFR was more strongly associated than estimated GFR with sequelae of CKD (hyperparathyroidism, anemia, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, and hyperphosphatemia).13

Our findings raise a few interesting questions. First, they do not support the conventional view that iGFR is in fact the “gold standard” measure of renal function. Much research effort in CKD recently has been directed at deriving ever better equations to estimate GFR. But if the current equations produce eGFR values that already perform very similar to measured iGFR, perhaps future research effort can be directed elsewhere. Second, many large clinical studies have devoted considerable resources and effort to measure GFR directly.14 Some future studies may not need to adopt the same approach if iGFR is not superior to eGFR in explaining CKD comorbidities. Third, if iGFR explains a relatively small proportion, the observed variation of the consequences of CKD, perhaps we should reassess the expectation that a single parameter can serve as a sufficient “overall index” of renal function. It may be more appropriate to adopt a more multidimensional concept of “kidney function,” incorporating other key physiologic parameters such as proteinuria, metabolic activities, or degree of perturbation of the “milieu intérieur” (reflecting, perhaps, imbalance between “demand” of and “supply” for renal function).

Several aspects of the study design should be mentioned. A cross-sectional study design was selected because our goal was to analyze how iGFR or eGFR are associated with concurrent rather than future metabolic abnormalities. We decided, a priori, not to examine hyperparathyroidism and PTH level as an outcome because some individuals with CKD will have low-turnover bone disease and low PTH levels, even at relatively low GFR levels. Thus, the association between PTH and GFR may be U-shaped and unsuitable for linear regression analysis (although when this was later examined as an outcome, iGFR was also not superior to eGFR_Cr or eGFR_cysC). We chose, a priori, not to examine the association between decreased GFR and other outcomes that have been previously shown to be associated with CKD, such as indices of physical health status, cognitive function, or cardiovascular disease. This is because the pathophysiological links between CKD and these indices or cardiovascular disease are not entirely clear and confounding may bias any observed associations. Hence, we thought these outcomes were less compelling to use as a proxy of renal function. In contrast, few will dispute that the four outcomes we considered—anemia, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia—are consequences of reduced renal function. There is a large body of pathophysiological literature mechanistically linking reduced renal function to each one.

The limitations of this study include the fact that the mean coefficient of variation for our iGFR measurements was 13.8%. However, given that this is the precision achievable in a research study, the errors in the clinical setting would likely be even greater. Since GFR is known to vary with dietary protein intake, time of day, and posture, efforts were made in CRIC to decrease variability in 125I-iothalamate clearance results by performing all measurements after consumption of only a low protein (<10 g) meal, in the supine or sitting position, and at approximately the same time of day. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents taken on an as-needed basis (i.e., not taken daily as a maintenance medication) were withheld for at least 48 h before each iGFR test. The intrinsic complexity of the iGFR measurement introduces opportunities for errors. Some may argue that average of multiple iGFR measurements is the actual “gold standard,” although this would make this an even less practical measurement to implement, and a single iGFR has been considered the “gold standard” in almost all prior studies. The CRIC Study did not enroll patients with normal renal function, so our results do not apply to other situations when direct measures of renal function are undertaken (e.g., in the evaluation of potential kidney donors). There clearly will be circumstances in which iGFR is indicated as a better measurement of kidney function than eGFR, especially creatinine-based eGFR, such as in a patient with an amputation or other substantial alterations in body composition/creatinine generation. CRIC enrollees are not representative of all CKD patients, so our results may not be generalizable to all subgroups. We acknowledge that there are numerous potential metrics for evaluating the strengths and limitations of iGFR, and our study is limited to a cross-sectional analysis of four surrogate outcomes. More studies are needed to refute or support, more definitively, the notion that iGFR is the “gold standard” measure of kidney function.

In conclusion, we found, in this large rigorous cross-sectional study of CKD patients, that direct iothalamate measured GFR (iGFR) was not consistently superior to serum Cr-based or cystatin C-bsaed estimated GFR (eGFR) in its association with four common CKD comorbid conditions. In addition, iGFR explained a small proportion the observed variation in severity of CKD sequelae. These results raise questions regarding the conventional view that iGFR is the “gold standard” measure of kidney function.

CONCISE METHODS

Study Population

This analysis used data from the baseline visit of Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. The CRIC Study is a NIH-sponsored multicenter observational cohort that enrolled patients from seven clinical centers located throughout the United States.4 Men and women with reduced eGFR, based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation, between the ages of 21 and 74 were eligible for the study. Entry criteria for CRIC varied by age: an estimated GFR of 20 to 70 ml/min/1.73m2 for those aged 21 to 44 yr old; 20 to 60 ml/min/1.73m2 for those aged 45 to 64 yr old; and 20 to 50 ml/min/1.73m2 for those aged 65 to 74 yr old. Persons with polycystic kidney disease, multiple myeloma, or glomerulonephritis on active immunosuppression, and kidney transplant recipients were excluded. Also excluded were those with severe comorbid conditions (such as advanced heart failure, cirrhosis, HIV infection) that diminish ability to participate in a longitudinal study.

Enrollment started July 2003 and ended March 2007. (Additional enrollment of Hispanic participants continued through August 2008 in one center.)

By design, a random, weighted subsample (n = 1288) of approximately one third of original CRIC enrollees (n = 3612) was selected to undergo direct measurements of GFR by iothalomate clearance (with the additional exclusion criteria of known iodine allergy and impaired urinary voiding). The present analyses are based on this subcohort. In the current cross-sectional study, only the baseline measurements in CRIC were considered. We excluded 66 enrollees who were missing one renal function measurement (e.g., cystatin C) or outcome measurements (e.g., serum potassium) of interest, and eight who only had one iGFR period, resulting in a final study population of 1214. The same study population was used for all analyses.

Measures of Renal Function

Three measures of renal function were compared. First, we examined GFR measured directly by urinary clearance of iothalamate (iGFR). iGFR was conducted using a protocol similar to that in prior studies.15 Briefly, after a water load and administration of saturated solution of potassium iodine (SSKI), 125I-iothalamate was injected subcutaneously. After a 60- to 90-min waiting period, timed collections of urine and serum were performed. Urine flow rate was maintained above 1 ml/min. The goal was to obtain four timed urine collection periods bracketed by blood draws to measure plasma iothalamate levels (P). Concurrent urine counts (U) and urine volumes (V) for each period were determined. GFR was calculated as weighted average UV/P and corrected for body surface area. In CRIC, 88% of subcohort enrollees had four or more urine collection periods, 6% had three, and 5% had two or fewer. It was noted that, among CRIC enrollees, iGFR measures from the first period of the test were systematically higher than the time-weighted average of all testing periods, which could be explained by a lack of equilibrium reached in a substantial number of 125I-iothalamate GFR tests. Therefore, the CRIC Steering Committee decided to eliminate the first period of the iGFR measure in all primary CRIC analyses involving iGFR data. The mean coefficient of variation (CV) for the iGFR was 13.8%, excluding the first period. In sensitivity analysis, first period values were included.

Second, we examined eGFR based on serum creatinine (Cr) calculated from the 4-variable MDRD equation (eGFR_Cr) as follows: 186*serum Cr−1.154*age−0.203* (0.742 if female)*(1.212 if black).16,17 Serum Cr measurements were done in the CRIC central laboratory at University of Pennsylvania on the Hitachi Vitros 950 AT (CV 1.1%) and calibrated to the MDRD central laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic.18

Third, we examined eGFR based on a cystatin C (cysC) equation (eGFR_cysC): 127.7 * cysC−1.17 * age−0.13 (*0.91 if female)(*1.06 if black).19 Cystatin C was measured using a Siemens BNII machine at the CRIC Central laboratory with a CV 4.9%. An internal standardization was implemented to correct for a drift over time when using different calibrator lots and reagent lots manufactured by Siemens. Specifically, all Cystatin C values were calibrated to the combination of calibrator lot 51 and reagent lot 40.

Outcomes Evaluated

We, a priori, chose to examine four parameters that are well known to be altered by reduced renal function: levels of hemoglobin, potassium, bicarbonate, and phosphorus.20–23

Hemoglobin was measured locally at each CRIC clinical center. Electrolytes were measured at the CRIC Central Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania. Specifically, serum potassium (CV 1.2%) and phosphorus (CV 0.9%) were measured on Hitachi Vitros 950 AT and serum bicarbonate (CV 4.5%) on Beckman Coulter CxC.

Outcomes were analyzed both as continuous and as dichotomous variables. For the latter, we chose, a priori, the upper and lower limits reported by the University of Pennsylvania central laboratory. Thus, anemia was defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dl in men and <12 g/dl in women, hyperkalemia as serum potassium >5.3 mmol/L, metabolic acidosis as serum bicarbonate <22 mol/L, and hyperphosphatemia as serum phosphorus >5 mg/dl.

Statistical Analysis

Before analysis, we specified the three renal function measurements and four outcome measurements, as well as the dichotomous cut-offs, as described above. When the outcomes were considered as continuous variables, we used linear regression to examine the relative contributions of the three GFR measures. Initial exploratory analyses, including smoothing methods and residual analysis, suggested that linear associations were adequate to capture primary predictions, and these relationships were used for the remainder of the evaluations. (Formal analysis using spline models did not yield any material improvement in fit of the models or alter our main results.) When the outcomes were dichotomized, we used logistic regression. R-squared values and C-statistics were used to assess adequacy of the models, respectively. The C-statistic is the area under the curve (AUC) for the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Since the absolute GFR values and distributions are not identical across the three GFR measurements, in a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the models using per change in SD of measure rather than per change in 10 ml/min/1.73m.2

Because medications may impact some of the clinical outcomes, we repeated the analysis involving hemoglobin/anemia as outcome after eliminating those patients on erythropoiesis stimulating agents (including epoetin alpha, epoetin beta, and darbepoetin alpha); we repeated the analysis involving potassium/hyperkalemia as outcome after eliminating those patients on sodium polystyrene sulfonate (kayexalate); we repeated the analysis involving bicarbonate/metabolic acidosis as outcome after eliminating those patients on alkali therapy, which can be used to treat metabolic acidosis (including sodium bicarbonate, potassium citrate, sodium citrate); and we repeated the analysis involving phosphorus level/hyperphosphatemia as outcome after eliminating those patients on phosphorus binders (including calcium acetate, calcium carbonate, lanthanum, and sevelamer). We also performed subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, race, and iGFR range, and we explored the effect of adjusting for age, sex, and race on our results.

In addition to univariable models, including the GFR measures singly, we also examined bivariable models to evaluate whether the two eGFR measurements significantly contributed independent information once iGFR was known.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the CRIC Study was obtained under a cooperative agreement from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U01DK060990, U01DK060984, U01DK061022, U01DK061021, U01DK061028, U01DK60980, U01DK060963, and U01DK060902). In addition, this work was supported, in part, by 5K24DK002651, University of Pennsylvania CTRC CTSA UL1 RR-024134, Johns Hopkins University UL1 RR-025005, University of Maryland GCRC M01 RR-16500, Case Western Reserve University Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (University Hospitals of Cleveland, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and MetroHealth) UL1 RR-024989, University of Michigan GCRC grant number M01 RR-000042 CTSA grant number UL1 RR-024986, University of Illinois at Chicago CTSA UL1RR029879, Tulane/LSU/Charity Hospital General Clinical Research Center RR-05096, Kaiser NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI UL1 RR-024131. We would like to thank the technical assistance of Hank Rolins and Nancy Robinson.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Is There Something Better than the Best Marker of Kidney Function?,” on pages 1779–1781.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hsu CY: Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed., edited by Greenberg A. Philadelphia, Elsevier Saunders, 2009, pp 19–23 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G: The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med 330: 877–884, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, Beck G, Bourgoignie J, Briggs JP, Charleston J, Cheek D, Cleveland W, Douglas JG, Douglas M, Dowie D, Faulkner M, Gabriel A, Gassman J, Greene T, Hall Y, Hebert L, Hiremath L, Jamerson K, Johnson CJ, Kopple J, Kusek J, Lash J, Lea J, Lewis JB, Lipkowitz M, Massry S, Middleton J, Miller ER, 3rd, Norris K, O'Connor D, Ojo A, Phillips RA, Pogue V, Rahman M, Randall OS, Rostand S, Schulman G, Smith W, Thornley-Brown D, Tisher CC, Toto RD, Wright JT, Jr, Xu S: Effect of ramipril vs amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc 285: 2719–2728, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, Cifelli D, Cizman B, Daugirdas J, Fink JC, Franklin-Becker ED, Go AS, Hamm LL, He J, Hostetter T, Hsu CY, Jamerson K, Joffe M, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Lash JP, Miller ER, Mohler ER, 3rd, Muntner P, Ojo AO, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Wright JT: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: Design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: S148–S153, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koopman MG, Koomen GC, Krediet RT, de Moor EA, Hoek FJ, Arisz L: Circadian rhythm of glomerular filtration rate in normal individuals. Clin Sci 77: 105–111, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen HP, Hovind P, Jensen BR, Parving HH: Diurnal variations of glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 61: 163–168, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wan LL, Yano S, Hiromura K, Tsukada Y, Tomono S, Kawazu S: Effects of posture on creatinine clearance and urinary protein excretion in patients with various renal diseases. Clin Nephrol 43: 312–317, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hostetter TH: Human renal response to meat meal. Am J Physiol 250: F613–618, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hsu CY, Chertow GM, Curhan GC: Methodological issues in studying the epidemiology of mild to moderate chronic renal insufficiency. Kidney Int 61: 1567–1576, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Menon V, Shlipak MG, Wang X, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens L, Kusek JW, Beck GJ, Collins AJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ: Cystatin C as a risk factor for outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 147: 19–27, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, Hillege HL, de Zeeuw D, Curhan GC, de Jong PE: Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int 65: 1416–1421, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taglieri N, Koenig W, Kaski JC: Cystatin C and cardiovascular risk. Clin Chem 55: 1932–1943, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moranne O, Froissart M, Rossert J, Gauci C, Boffa JJ, Haymann JP, M'Rad MB, Jacquot C, Houillier P, Stengel B, Fouqueray B: Timing of onset of CKD-related metabolic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 164–171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xie D, Joffe MM, Brunelli SM, Beck G, Chertow GM, Fink JC, Greene T, Hsu CY, Kusek JW, Landis R, Lash J, Levey AS, O'Conner A, Ojo A, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Wang H, Feldman HI: A comparison of change in measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate in patients with nondiabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1332–1338, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levey AS, Berg RL, Gassman JJ, Hall PM, Walker WG: Creatinine filtration, secretion and excretion during progressive renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl 27: S73–S80, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D: A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130: 461–470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ: A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 155A [abstract], 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joffe M, Hsu CY, Feldman HI, Weir M, Landis JR, Hamm LL: Variability of creatinine measurements in clinical laboratories: results from the CRIC study. Am J Nephrol 31: 426–434, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, Feldman HI, Froissart M, Kusek J, Rossert J, Van Lente F, Bruce RD, 3rd, Zhang YL, Greene T, Levey AS: Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: A pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 395–406, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hsu CY, Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, Curhan GC: Relationship between hematocrit and renal function in men and women. Kidney Int 59: 725–731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Curhan GC: Epidemiology of anemia associated with chronic renal insufficiency among adults in the Unites States: Results from NHANES III. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 504–510, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace JA, Coresh J: Association of kidney function with anemia: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994). Arch Intern Med 162: 1401–1408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu CY, Chertow GM: Elevations of serum phosphorus and potassium in mild to moderate chronic renal insufficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1419–1425, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]