Abstract

To further characterize the function of the Borrelia burgdorferi C-terminal protease CtpA, we used site-directed mutagenesis to alter the putative CtpA cleavage site of one of its known substrates, the outer membrane (OM) porin P13. These mutations resulted in only partial blockage of P13 processing. Ectopic expression of a C-terminally truncated P13 in B. burgdorferi indicated that the C-terminal peptide functions as a safeguard against misfolding or mislocalization prior to its proteolytic removal by CtpA. In a parallel study of Borrelia burgdorferi lipoprotein sorting mechanisms, we observed a lower-molecular-weight variant of surface lipoprotein OspC that was particularly prominent with OspC mutants that mislocalized to the periplasm or contained C-terminal epitope tags. Further investigation revealed that the variant resulted from C-terminal proteolysis by CtpA. Together, these findings indicate that CtpA rather promiscuously targets polypeptides that lack structurally constrained C termini, as proteolysis appears to occur independently of a specific peptide recognition sequence. Low-level processing of surface lipoproteins such as OspC suggests the presence of a CtpA-dependent quality control mechanism that may sense proper translocation of integral outer membrane proteins and surface lipoproteins by detecting the release of C-terminal peptides.

INTRODUCTION

Borrelia spirochetes, the etiological agents of vector-borne Lyme borreliosis and relapsing fever, are diderm bacteria (bacteria with both an inner and outer membrane) with an unusual envelope structure (reviewed in reference 6). As in Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, a periplasmic space separates an inner cytoplasmic membrane (IM) from an outer membrane (OM) (26), but flagella remain sequestered in the periplasm, where they provide both motility and determine bacterial shape (34). Similarly, the Borrelia OM also contains integral membrane proteins (23, 43, 56), including the porins P66 (15, 41, 51) and P13 (39, 45), as well as BesC, a component of an envelope-spanning type I secretion system involved in virulence and antibiotic resistance (11). However, the cell envelope lacks the lipopolysaccharide coat that typifies Gram-negative bacteria (54). Instead, the borrelial surface is covered by abundant glycolipids (4, 5, 22) and surface lipoproteins (9) such as OspC, a virulence factor that is required for the establishment of mammalian infection upon arthropod-borne transmission (20, 44, 53, 55).

Our current understanding of posttranslational protein processing and modification in Borrelia burgdorferi is limited. Based on studies in other Gram-negative or diderm model organisms, lipoproteins are likely modified in a three-step process occurring on the periplasmic face of the IM, involving cleavage by the signal II peptidase Lsp (encoded by open reading frame [ORF] BB0469). Surprisingly, the small B. burgdorferi genome contains genes encoding three signal peptidase I paralogues, LepB1 to LepB3 (BB0030, BB0031, and BB0263) with currently undescribed functions; at least one of them is expected to process nonlipidated exported proteins. Likewise, the proposed role of the borrelial DegP/HtrA homologue (BB0104) in protein quality control (25) awaits determination.

Östberg and colleagues identified CtpA (BB0359) as a B. burgdorferi homologue of carboxyl-terminal proteases, a family of unusual serine-like proteases (38). Inactivation of ctpA had a pleiotropic effect on the B. burgdorferi proteome, affecting the processing of both lipidated and nonlipidated OM-associated proteins, including the OM porin P13 (37–39). Mass spectrometry showed that P13 is modified at both the amino (N) and carboxy (C) termini: the first 19 amino acids are probably removed by one of the annotated signal peptidase I LepB paralogues, while 28 C-terminal amino acids are removed by CtpA, most likely in the periplasm as well (36, 37). Although the preserved OM localization of P13 in the ΔctpA strain indicated that proper targeting was not dependent on C-terminal cleavage, it did not rule out a function of the C-terminal peptide in initiating translocation to the outer membrane.

In this study, we modified the C terminus of P13 to determine the fate of P13 lacking the C-terminal peptide and to begin addressing the enzymatic specificity of CtpA. In a related set of experiments, we identified the molecular basis of a recent observation regarding B. burgdorferi OspC secretion, where periplasmic or C-terminally tagged mutants of OspC produced a lower-molecular-mass variant that apparently resulted from C-terminal cleavage (28). Our results indicate the following. (i) The P13 C-terminal peptide is required for stability and targeting of P13 to the OM. (ii) Periplasmic and C-terminally tagged OspC mutants, but also the wild-type OspC protein, are substrates for CtpA. (iii) Processed P13 and OspC share an identical C-terminal Ala residue despite otherwise divergent peptide sequences. These findings represent important steps toward the definition of CtpA specificity and point to a potentially expanded role of CtpA-mediated processing in spirochetal envelope biogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Borrelia burgdorferi B31-A (7), B31-A ΔctpA (38), B31-A Δp13 (39), and B31-A3 (ΔospC) (provided by Patti Rosa, NIH/NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, MT) strains are derivatives of strain B31 (ATCC 35210). B. burgdorferi was cultured in liquid or solid BSK-II medium at 34 or 35°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere (2, 59). Selective BSK-II medium was supplemented with 200 μg/ml of kanamycin, 50 μg/ml of streptomycin, or 40 μg/ml of gentamicin (Sigma). Escherichia coli strains Top10 (Invitrogen) and XL-10 Gold (Stratagene) were used for plasmid construction and propagation. E. coli cultures were grown at 37°C in LB broth or LB agar (Difco) supplemented with 30 μg/ml of kanamycin, 100 μg/ml spectinomycin (Sigma), or 5 to 15 μg/ml of gentamicin.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Plasmids carrying mutant genes (Table 1) were constructed either by splicing overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) (21) with Pfx Platinum (Invitrogen) or Phusion Hotstart (New England BioLabs) thermostable proofreading DNA polymerases or by following the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). Oligonucleotides are listed in Table 2. Sequences were verified by DNA sequencing (AGCT Inc. [Wheeling, IL] or Northwestern University [Chicago, IL]).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Description, genotype, or phenotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Borrelia burgdorferi strains | ||

| B31-A | Clone of B31 ATCC 35210 (harboring cp26, cp32-1, cp32-2/7, cp32-3, cp32-9, lp17, lp28-1, lp28-2, lp28-3, lp36, lp54, and lp56) | 7 |

| B31-A ΔctpA | C-terminal protease A (ctpA) knockout, PflaB-kan insertion in ctpA (plasmid content is identical to B31-A) | 38 |

| B31-A Δp13 | Porin P13 (p13) knockout, PflaB-kan insertion in p13 (plasmid content is identical to B31-A) | 3 |

| B31-A3 (ΔospC) | Outer surface protein C (ospC) knockout, PflaB-kan insertion in ospC (lp25−) | K. Tilly and P. A. Rosa (28) |

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| Top10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| XL-10 Gold | Tetr Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr) Amy Camr] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKFSS1 | Shuttle vector (Strr) | 19 |

| pOSK200 | pKFSS1::PflaB-ospC | 28 |

| pOSK307 | pKFSS1::PflaB-ospC-his | 28 |

| pBSV2G+ctpA | pBSV2G::ctpA | 38 |

| pOSK326 | pKFSS1::PflaB-ospCA204X | This study |

| pOSK360 | pKFSS1::PflaB-ospC-link | This study |

| pOSK277 | pKFSS1::PflaB-ospC-L2his | This study |

| pP13-148 | pBSV2G::p13L148A | This study |

| pP13-151 | pBSV2G::p13A151G | This study |

| pP13-148/151 | pBSV2G::p13L148A/A151G | This study |

| pP13-STOP | pBSV2G::p13A151STOP | This study |

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotidea | Sequence (5′ to 3′)b | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 326-fwd | CTTACAAGCCCTGTTGTGTAAGAAAGTCCAAAAAAACC | OspC A204X forward mutagenic primer |

| 326-rev | GGTTTTTTTGGACTTTCTTACACAACAGGGCTTGTAAG | OspC A204X reverse mutagenic primer |

| 360-fwd | CCCGGGGGCTCAGGTGCTTAACATCATCACCATCATTAATC | Forward primer to add a linker to OspC |

| 360-rev | GATTAATGATGGTGATGATGTTAAGCACCTGAGCCCCCGGGAGG | Reverse primer to add a linker to OspC |

| 277-fwd | CAAAAATTAGATGGATTGAAACATCATCATCATCATCACAATGAAGGATTAAAG | Internal ospC-L2His tag insertion forward primer |

| 277-rev | CCTTTAATCCTTCATTGTGATGATGATGATGATGTTTCAATCCATCTAATTTTTG | Internal ospC-L2His tag insertion reverse primer |

| p13-SacI-f | GCTCTATTGAGCTCCGAATTTCAAGC | P13 cloning forward primer containing the SacI restriction site |

| p13-PstI-r | CAATTGCACTGCAGAATTGCAATCACC | P13 cloning reverse primer containing the PstI restriction site |

| p13-L148A-f | GGAAGCTAAAAAATAGCCGATTACATCGATTAGGAGGATTTGAACCTAG | P13 L148A forward mutagenic primer |

| p13-L148A-r | CTAGGTTCAAATCCTCCTAATCGATGTAATCGGCTATTTTTTAGCTTCC | P13 L148A reverse mutagenic primer |

| p13-A151G-f | GGAAGCTAAAAAATAGCGAATTACATCCTTTAGGAGGATTTGAACCTAG | P13 A151G forward mutagenic primer |

| p13-A151G-r | CTAGGTTCAAATCCTCCTAAAGGATGTAATTCGCTATTTTTTAGCTTCC | P13 A151G reverse mutagenic primer |

| p13-AG/LA-f | GGAAGCTAAAAAATAGCCGATTACATCCTTTAGGAGGATTTGAACCTAG | P13 L148A/A151G forward mutagenic primer |

| p13-AG/LA-r | CTAGGTTCAAATCCTCCTAAAGGATGTAATCGGCTATTTTTTAGCTTCC | P13 L148A/A151G reverse mutagenic primer |

| p13-STOP-f | GGAAGCTAAAAAATAGCGAATTACATCGAATTGGAGGATTTGAACCTAG | P13 A151STOP forward mutagenic primer |

| p13-STOP-r | CTAGGTTCAAATCCTCCAATTCGATGTAATTCGCTATTTTTTAGCTTCC | P13 A151STOP reverse mutagenic primer |

At the end of the oligonucleotide designation, fwd and f indicate forward and rev and r indicate reverse.

The restriction sites and mutated codon sequences are underlined.

Transformation.

Chemically competent E. coli bacteria were prepared and transformed as described previously (46). Electrocompetent B. burgdorferi bacteria were prepared and transformed using a Bio-Rad MicroPulser electroporator, and single clones were obtained as described previously (47, 52). Transformants were assayed for the respective recombinant plasmid by PCR using specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 2).

Plasmid profiling.

The plasmid content of B. burgdorferi strains was determined by single or multiplex PCR with plasmid-specific primer sets (12, 29, 42). B. burgdorferi B31-A, B31-A ΔctpA, and B31-A Δp13 strains were determined to harbor plasmids cp26, cp32-1, cp32-2/7, cp32-3, cp32-9, lp17, lp28-1, lp28-2, lp28-3, lp36, lp54, and lp56; B. burgdorferi B31-A3 (ΔospC) is a low-passage, transformable clone lacking lp25 (data not shown).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Proteins were solubilized in sample buffer, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (12.5% or 10% polyacrylamide), and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. For the P13-related studies, NuPAGE sample buffer and 12% NuPAGE bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) were used. For immunoblots, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-NC nitrocellulose (Millipore) or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) (PALL Corporation) membranes using a Transblot semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad). The membranes were rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (20 mM Tris–500 mM NaCl [pH 8.0]). TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) containing 5% dry milk was used for membrane blocking and subsequent incubation with primary and secondary antibodies; TBST alone was used for the intervening washes. The antibodies used were anti-CtpA rabbit polyclonal antiserum (38) (1:100 dilution), anti-FlaB rat polyclonal antiserum (1) (1:4,000 dilution; a gift from M. Caimano, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT), anti-OspA mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) H5332 (3) (1:50), anti-OspC mouse MAb (33) (1:50; a gift from B. Stevenson, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY), anti-P13 rabbit polyclonal antiserum (37) (1:1,000), anti-P66 mouse MAb H914 (14) (1:500), and anti-His MAb (HIS-1; Sigma-Aldrich) (1:100). Secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L), goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) (Sigma), or peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (Dako A/S) (all used at 1:30,000). As an alternative to the anti-His MAb, a HisProbe Ni2+-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Pierce) (1:5,000) was used. Alkaline phosphatase substrates were 1-Step nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT)/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) (Pierce) for colorimetric detection and CDP-Star (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) for chemiluminescence detection. Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were used as the peroxidase substrates according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Protein localization assays.

To assess protein surface exposure by protease accessibility, intact B. burgdorferi cells were treated in situ with proteinase K as described previously (13, 50). To assess protein membrane association, B. burgdorferi cells were subjected to phase separation with Triton X-114 (Sigma) as described previously (10, 43). Briefly, harvested B. burgdorferi cells were solubilized overnight in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing Mg (PBS-Mg) and 2% (vol/vol) Triton X-114 with rotation at 4°C. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was phase separated at 37°C for 15 min and centrifuged to obtain the aqueous periplasmic and detergent-soluble membrane fractions. Both the aqueous and detergent fractions were washed three times by the addition of ice-cold Triton X-114 to the aqueous phase at a final concentration of 2% or by the addition of ice-cold PBS-Mg to detergent phase and phase separated as described above. Proteins were concentrated by acetone precipitation. Outer membrane protein “B-fractions” of B. burgdorferi B31-A, B31-A Δp13, B31-A ΔctpA, and B31-A Δp13 strains carrying shuttle vectors harboring mutated variants of P13 were prepared by octyl-glucopyranoside extraction as described elsewhere (32).

OspC immunoprecipitation and in-gel digestion with cyanogen bromide.

A total of 2.5 × 109 B. burgdorferi cells grown to late exponential phase (5 × 107 cells ml−1) were harvested, washed three times with PBS-Mg, and lysed in IGEPAL lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1% IGEPAL, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). After preclearing by incubation with protein A beads (GE) for 1 h at 4°C with end-over-end rotation, the lysate was incubated with 10 μg of purified anti-OspC MAb (33) (a gift from R. Gilmore, CDC, Fort Collins, CO) for 1 h at 4°C. Protein A beads were added to the lysate at 4°C for 1 h. The beads were washed three times with IGEPAL lysis buffer and once with 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0). The beads were then incubated in SDS-PAGE loading dye with 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and boiled, and the supernatant was separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie blue (Invitrogen), rinsed with double-distilled H2O (ddH2O), and the stained OspC* band was excised from the gel. The gel slice was incubated in 100 μl of 50% acetonitrile (Fisher) for 10 min followed by incubation with 100 μl of 100% acetonitrile for an additional 10 min. The acetonitrile was removed, and the gel slice was rehydrated with 500 μl of ddH2O. The ddH2O was removed, and the 50% and 100% acetonitrile incubations were repeated. The gel slice was then air dried for 10 to 15 min followed by incubation in 100 μl of 10 to 30 mg/ml cyanogen bromide (CNBr) in 70% formic acid (Sigma) for 48 h in the dark (24, 48). All steps were performed at room temperature. The liquid supernatant was removed from the gel slice, lyophilized in a SpeedVac concentrator (Savant ThermoScientific), and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of ddH2O to terminate the reaction. The lyophilization process was repeated, and the product was resuspended in 30 μl of ddH2O for analysis by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS).

LC-MS-MS.

The CNBr-derived peptide mixture was separated on a microcapillary C18 column (PicoFrit; New Objective) that was coupled to the nanospray ionization source of an LCQ DECA XP Plus ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan). Peptides were eluted from the column over 45 min in a 5 to 95% acetonitrile gradient in an aqueous solution of 0.1% formic acid and electrosprayed into the mass spectrometer directly from the column. Full MS and tandem MS spectra were recorded and analyzed by the BioWorks 3.2 software based on a SEQUEST algorithm (18), as well as by the MassMatrix 2.2.3 software (58).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Determination of CtpA specificity using P13 mutants.

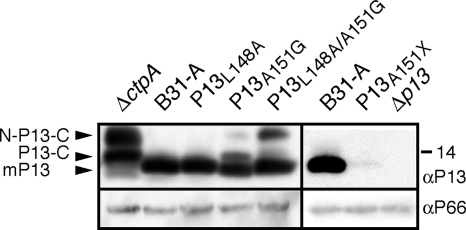

To further characterize the proteolytic activity of the Borrelia burgdorferi C-terminal protease CtpA, we selected P13, a well-described Borrelia porin and known CtpA substrate (38, 39), as the first model protein. Prior studies had shown that CtpA-dependent P13 cleavage occurs after or up to Ala151 (37, 38) (Fig. 1). To investigate whether CtpA recognizes a specific amino acid sequence, we introduced several amino acid substitutions around the predicted cleavage site (Fig. 1) by site-directed mutagenesis of a recombinant plasmid carrying the p13 gene under the control of a constitutive B. burgdorferi flagellar promoter. The original and mutated plasmids were then used to transform the B. burgdorferi B31-A-derived Δp13 knockout strain B31-A (Δp13) to express wild-type P13 (P13wt), P13 with the L148A substitution (P13L148A), and P13 with the A151G substitution (P13A151G). Outer membrane protein preparations were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with polyclonal antibody against P13 (Fig. 2). Used as controls, P13 endogenously expressed in the presence of CtpA in strain B31-A yielded an easily detectable 13-kDa band, while the expected pattern of unprocessed and partially processed P13 (37, 38) was observed in the isogenic ΔctpA strain. No detectable change in the amount of mature P13 was observed when the P13L148A substitution mutant was expressed in strain B31-A (Δp13). In contrast, the P13A151G substitution affected processing, as partially processed pro- and unprocessed prepro-P13 bands could be observed in the Western blot. A more pronounced effect on processing could be seen in the P13L148A/A151G mutant containing both substitutions. However, mature P13 remained the most prominent protein species observed in all samples. This suggested that CtpA does not have a strict primary peptide sequence requirement for substrate recognition.

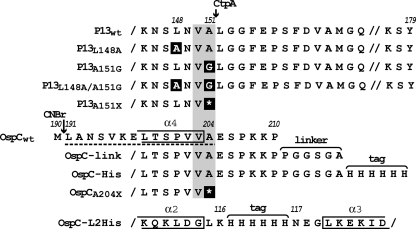

Fig. 1.

Partial peptide sequences of wild-type (wt) and mutant P13 and OspC proteins. P13 amino acid substitutions are shown on a black background, and the positions of amino acid substitutions in the mutant are indicated above the sequence. The residues confined to the α-helices of OspC are boxed and numbered. Residue numbers of the signal peptide-containing pro-OspC lipoprotein are shown above the sequences. The linker and epitope tag sequence are indicated by labeled brackets. The predicted CtpA cleavage site is indicated by the gray shading. The CtpA-dependent C-terminal peptide identified by LC-MS-MS after CNBr cleavage of gel-purified OspC* is shown underlined with a broken line. Note that the C terminus of P13 is cleaved after an Ala residue (38) (see text also).

Fig. 2.

Processing of C-terminal P13 mutants. Western immunoblots of outer membrane protein preparations obtained from cells expressing wild-type (B31-A) or mutant P13 proteins. P13 was detected by a polyclonal rabbit antibody. The positions of unprocessed prepro-P13 (N-P13-C), N-terminally processed pro-P13 (P13-C), and mature P13 (mP13) are indicated by black arrowheads to the left of the panel. The position of the 14-kDa molecular mass marker is indicated to the right of the panel. P66 was used as a loading control and detected using monoclonal antibody H914. αP13, anti-P13 antibody.

Roles of the P13 C terminus in secretion and targeting.

Östberg and colleagues previously speculated that P13 processing by CtpA may be required for correct assembly of the predicted multimeric state of P13 (37, 38). The biological purpose of P13's C-terminal peptide, however, remained unclear. As the C terminus is “discarded” in the periplasm, we hypothesized that it somehow protected the highly hydrophobic P13 peptide during transport through the inner membrane (IM) or in the initial steps of traversing the periplasm. We therefore generated a truncated P13 protein that lacked the C-terminal peptide by replacing the Ala151 codon with a stop codon. Compared to P13wt, P13A151X was detected at only very low levels in the outer membrane (OM) fraction (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed in immunoblots of whole-cell preparations (data not shown). This indicated that P13 lacking the C-terminal sequence was significantly destabilized, i.e., most likely degraded by cellular proteases due to misfolding or mistargeting. While the latter proteases remain to be determined, the data confirmed the intramolecular chaperone-like function of P13's C terminus.

Specificity of OspC C-terminal processing.

As part of our analysis of the requirements for proper targeting of B. burgdorferi surface lipoprotein OspC, we previously introduced mutations within the N-terminal OspC tether peptide. These mutations led to mislocalization of OspC to the periplasm. A common trait of these predominantly periplasmic OspC mutants was the presence of an additional protein band (labeled OspC*) that reacted with an anti-OspC mouse MAb but at about 19 kDa had a lower apparent molecular mass than the 21-kDa wild-type OspC. Expression of a C-terminally hexahistidine-tagged OspC (OspC-His) also yielded an OspC* band that did not react with a His epitope-specific antibody or Ni2+ conjugate. We therefore concluded that OspC* resulted from C-terminal cleavage (28). This evoked the C-terminal processing of P13 and hinted at the involvement of a similar, if not identical, processing pathway.

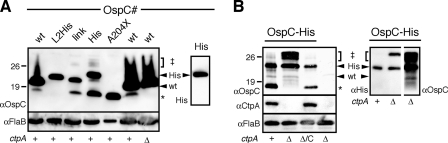

We first set out to further define the substrate requirements for OspC C-terminal processing and modified the recombinant OspC-His expression plasmid pOSK200 (28) (Table 1) by oligonucleotide-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (Table 2), yielding two recombinant plasmids (i) expressing OspC-link, an OspC-tagged with a C-terminal PGGSGA linker peptide also present in OspC-His, or (ii) OspC-L2His, an OspC with a His tag inserted between residues Lys116 and Asn117 in loop 2 (Fig. 1) (27). Both constructs were used to transform B. burgdorferi B31-A3 (ΔospC), an OspCwt-deficient background strain used in the previous studies (28) (Table 1). Whole-cell protein preparations were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed for OspC MAb-reactive bands by Western immunoblotting. The results showed that the addition of the 6-amino-acid linker peptide alone in OspC-link was sufficient to stimulate cleavage. Conversely, OspC-L2His did not yield an apparent OspC* band. Intriguingly, we observed a minor band derived from wild-type OspC that comigrated with OspC* (Fig. 3A). This indicated that even wild-type surface OspC was C-terminally processed, albeit at a relatively low incidence, but that processing could be specifically stimulated by the addition of unordered peptides to the lipoprotein's C terminus.

Fig. 3.

CtpA-dependent proteolytic processing of OspC. Western immunoblots of whole-cell protein preparations obtained from cells expressing wild-type (wt) or mutant OspC proteins in CtpA-expressing or CtpA-deficient strain backgrounds. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of each large gel. To the right of the large gels, the bracket and ‡ symbol denote the three higher-molecular-weight OspC‡ bands, black arrowheads point to the OspCwt or OspC-His protein bands, and an asterisk marks the position of the OspC* band. (A) All OspC mutants are expressed in the B. burgdorferi B31-A3 (ΔospC) ctpA+ (+) background; OspCwt is expressed in both the ctpA+ and B31-A ΔctpA (Δ) background (Table 1). Note that endogenous OspC expression in the B31-A ΔctpA strain is negligible (panel B, rightmost lane). (Left) The OspCwt sample was loaded twice (leftmost wt lane and middle wt lane) to visualize and compare the mobility of the OspCwt-derived OspC* band with the OspC* band seen with the OspC mutants. FlaB was used as a loading control. (Right) A HisProbe Ni2+-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Pierce) was used to confirm the mobility of the OspC-His band. (B) The strain background is indicated by ctpA phenotype below the gel as follows: +, B31-A strain; Δ, B31-A ΔctpA mutant strain; Δ/C, B31-A ΔctpA/pBSV2G+ctpA complemented strain (Table 1). (Left) CtpA was detected by a polyclonal rabbit antibody. FlaB served as a loading control. (Right) Whole-cell protein preparations separated by SDS-PAGE in adjacent lanes, blotted, and probed with His and OspC antibodies (αOspC, anti-OspC antibody). Note that anti-His reacts only with the topmost OspC‡ band. Other labels are identical to those used in Fig. 3A.

CtpA-mediated C-terminal processing of OspC.

To probe CtpA's involvement in the processing of OspC, we transformed the ctpA knockout mutant B31-A ΔctpA, its complemented derivative B31-A ΔctpA/pBSV2G+ctpA (38), and its parent strain B31-A (7) with the recombinant plasmid carrying a gene(s) encoding OspC-His (Fig. 1 and Table 1). In Western immunoblot assays, the OspC-His-derived OspC* band was not detectable in the ctpA knockout strain, but it was present in the CtpA-expressing B31-A background and in the complemented ctpA deletion strain (Fig. 3B). Also, OspCwt-expressing cells produced an OspC* band only in the presence of CtpA (Fig. 3A [note that the OspCwt sample is loaded twice to demonstrate specificity and comigration of the OspC* variant derived from the tagged and untagged OspC proteins]). This corroborated CtpA's involvement in the C-terminal processing of OspC.

Determination of the processed OspC C terminus.

To narrow down the extent of the C-terminal OspC peptide removed by CtpA, we truncated OspC beyond the C-terminal α-helix (30) by replacing Ala204 with a stop codon by site-directed mutagenesis of pOSK200 (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1). The OspCA204X and OspC* proteins migrated similarly on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, as detected by Western immunoblotting with the OspC MAb (Fig. 3A). We thus concluded that CtpA removed OspC's disordered C-terminal residues, cleaving at or close to Ala204. To determine the C terminus of OspC*, we took advantage of an internal CNBr cleavage site in OspC (Fig. 1) that would generate a C-terminal peptide with a specific mass, which could be confirmed by liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS). OspC* was purified from a Coomassie blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the CNBr-derived peptide mixture was analyzed. The search for MS-MS spectra/sequence matches in the B. burgdorferi database by BioWorks 3.2 software yielded a match of MS-MS spectra with peptide LANSVKELTSPVVA on three separate occasions (XCor scores of 3.0, 2.9, and 2.6; data not shown). No other versions of the C-terminal peptide were found with the search parameters set to retain spectra/sequence matches with XCor scores higher than 1.5 for peptides charged +1, an XCor score of 2.0 for peptides charged +2, and an XCor score of 2.5 for peptides charged +3. We therefore concluded that CtpA-mediated cleavage of OspC indeed produced an OspC* variant with a C-terminal Ala204. Hence, the ultimate C-terminal residues of CtpA-cleaved P13 and OspC were identical despite otherwise divergent C-terminal peptides (37).

Apparent N-terminal OspC processing defects in the absence of CtpA.

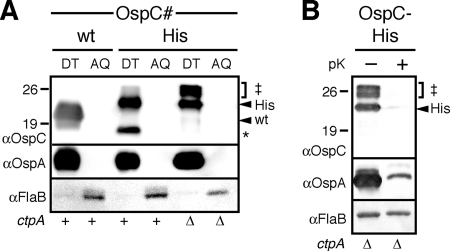

In addition to the OspC* and full-length OspC-His protein bands, three higher-molecular-weight variants with molecular masses around 26 kDa (labeled OspC‡) were prominent in immunoblots of the ctpA knockout strain with the anti-OspC MAb (Fig. 3B). Only the largest OspC‡ band reacted with the anti-His MAb, suggesting that the variants originated from both OspCwt and OspC-His expressed by the B. burgdorferi B31-A derivatives (Fig. 3B). Triton X-114 partitioning and proteolytic shaving assays performed as described previously (9, 13, 35, 50) indicated that both OspC* and OspC‡ protein species were associated with the membrane (Fig. 4A) and were surface exposed (Fig. 4B). Östberg and colleagues had previously observed higher-molecular-mass variants of P13 in the ctpA knockout and speculated that they may result from the incomplete removal of its N-terminal type I signal peptide by signal peptidase I (38). Analogously, treatment of Borrelia cells with the signal peptidase II inhibitor globomycin was shown to yield higher-molecular-mass lipoprotein species (16). Therefore, incomplete N-terminal OspC processing best explains the OspC‡ variants. Nevertheless, it remains perplexing that such a defect would not impact the variants' surface localization. It is conceivable that (i) the partial acylation of the N-terminal cysteine, which generally occurs before signal peptide cleavage, is sufficient for membrane anchoring, and that (ii) the accumulating nonmature lipoproteins eventually overwhelm secretion substrate checkpoints and ultimately reach the bacterial surface via the standard borrelial lipoprotein secretion pathway. Steady-state analyses as the ones performed here would be unlikely to detect the expected differences in secretion efficiencies.

Fig. 4.

Localization of CtpA-dependent OspC variants. Western immunoblots of protein preparations obtained from cells expressing wild-type (wt) or OspC-His proteins in CtpA-expressing or CtpA-deficient strain backgrounds. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated to the left of each gel. To the right of each gel, the three higher-molecular-weight OspC‡ bands are indicated by a bracket and ‡ symbol, black arrowheads point to the OspCwt or OspC-His protein bands, and an asterisk marks the position of the OspC* band. The strain background is indicated by ctpA phenotype below the gel as follows: +, B31-A3 (ΔospC) strain; Δ, B31-A ΔctpA strain. (A) Triton X-114 detergent (DT) and aqueous (AQ) protein fractions were probed. OspA and FlaB were used as membrane-associated and soluble controls, respectively. (B) Protease accessibility assay of the OspC-His-derived variant protein bands produced in a CtpA-deficient background. The cells had been treated with 200 μg/ml proteinase K (pK) (+) or had not been treated with proteinase K (−). OspA and FlaB were used as surface and subsurface controls, respectively.

Conclusions.

Our observation of CtpA-mediated cleavage of the surface lipoprotein OspC raises some intriguing questions regarding the protease's functional range. Despite having an identical Ala residue at the processed C terminus, the surrounding primary peptide sequences of P13 and OspC are not conserved (Fig. 1). This suggests that CtpA substrate recognition occurs at a higher than primary structural level. CtpA may recognize C-terminal peptides that lack confined secondary structure, such as the disordered OspC C terminus seen in protein crystals (17, 27). This “entropy-based” specificity would also explain why the addition of C-terminal epitope tag peptides stimulates CtpA-mediated proteolysis of OspC. Further exploration of this issue will require the structural analysis of other CtpA substrates, including P13. Initial topological studies of P13 mapped a surface-exposed loop and proposed an N-terminus-out/C-terminus-in topology separated by three transmembrane alpha-helices (37, 40). The latter secondary structural features would be highly unusual—although not unheard of— for an OM protein.

Unlike P13, OspC may be a mere target of opportunity for CtpA that becomes particularly attractive if its escape from the periplasm is hindered by mutations in its N-terminal tether peptide (28). However, the observed low-frequency C-terminal cleavage of wild-type OspC may also represent evidence for a quality control mechanism that senses proper translocation of surface lipoproteins by detecting the release of C-terminal peptides, potentially via the oligopeptide peptide permease complexes in the borrelial IM (8, 31, 50, 57). Disruption of such a mechanism may elicit a bacterial envelope stress response, which could be partially responsible for the secondary effects of ctpA deletion observed by Östberg et al. (38). Interestingly, the proteomic analysis of B. burgdorferi B31-A detected an about 20-kDa fragment of outer surface lipoprotein OspA that was not observed in the isogenic ctpA mutant (38). This suggested that the full-length 31-kDa OspA peptide was processed as well, albeit at a significantly more central site than OspC. Our earlier studies on OspA secretion (49, 50) may have missed any processing of B. burgdorferi OspA periplasmic mutants due to the low quantities and unexpected mobility of the fragment. It remains to be determined whether OspA cleavage is directly or indirectly linked to CtpA activity.

Our studies also show that the P13 C-terminal peptide plays a crucial role in escorting the porin on its way to the OM, most likely by stabilizing the proprotein in an intermediate conformation that remains compatible with the borrelial protein secretion machinery. Tests of our earlier stated hypothesis that P13's C-terminal domain may be required to avoid sorting of the predicted alpha-helical P13 domains to the IM via the Sec/YidC complex (6) are complicated by the apparent instability of the C-terminally truncated P13; future studies will likely require the inactivation of homologues of other cellular peptidases such as DegP/HtrA. Nonetheless, the answers presented here as well as the numerous open questions encourage further studies to define the proteolytic specificities and precise biological role(s) of B. burgdorferi CtpA as well as its substrates. Together, these analyses will provide additional insight into the role of posttranslational modifications in envelope biogenesis and host-pathogen interactions of this globally important spirochetal pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI063261 to W.R.Z. and in part by a T32-AI070089 Graduate Training Program in Multidimensional Vaccinogenesis fellowship to O.S.K.) and the Swedish Research Council (VR-M grant 07922 to S.B.).

We thank Brian Stevenson, Bob Gilmore, Melissa Caimano, and Patricia Rosa for supplying reagents and Ryan Schulze and Joe Lutkenhaus for helpful comments on the article.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akins D. R., et al. 1999. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect. Immun. 67:1526–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbour A. G. 1984. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J. Biol. Med. 57:521–525 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barbour A. G., Tessier S. L., Todd W. J. 1983. Lyme disease spirochetes and ixodid tick spirochetes share a common surface antigenic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody. Infect. Immun. 41:795–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belisle J. T., Brandt M. E., Radolf J. D., Norgard M. V. 1994. Fatty acids of Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 176:2151–2157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ben-Menachem G., Kubler-Kielb J., Coxon B., Yergey A., Schneerson R. 2003. A newly discovered cholesteryl galactoside from Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:7913–7918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergström S., Zückert W. R. 2010. Structure, function and biogenesis of the Borrelia cell envelope, p. 139–166 In Samuels D. S., Radolf J. D. (ed.), Borrelia: molecular biology, host interaction and pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press, Norwich, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bono J. L., et al. 2000. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 182:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bono J. L., Tilly K., Stevenson B., Hogan D., Rosa P. 1998. Oligopeptide permease in Borrelia burgdorferi: putative peptide-binding components encoded by both chromosomal and plasmid loci. Microbiology 144:1033–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brandt M. E., Riley B. S., Radolf J. D., Norgard M. V. 1990. Immunogenic integral membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi are lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 58:983–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brooks C. S., Vuppala S. R., Jett A. M., Akins D. R. 2006. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins. Infect. Immun. 74:296–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bunikis I., et al. 2008. An RND-type efflux system in Borrelia burgdorferi is involved in virulence and resistance to antimicrobial compounds. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bunikis I., Kutschan-Bunikis S., Bonde M., Bergström S. 2011. Multiplex PCR as a tool for validating plasmid content of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Microbiol. Methods 86:243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bunikis J., Barbour A. G. 1999. Access of antibody or trypsin to an integral outer membrane protein (P66) of Borrelia burgdorferi is hindered by Osp lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 67:2874–2883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bunikis J., Luke C. J., Bunikiene E., Bergström S., Barbour A. G. 1998. A surface-exposed region of a novel outer membrane protein (P66) of Borrelia spp. is variable in size and sequence. J. Bacteriol. 180:1618–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bunikis J., Noppa L., Bergström S. 1995. Molecular analysis of a 66-kDa protein associated with the outer membrane of Lyme disease Borrelia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 131:139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carter C. J., Bergström S., Norris S. J., Barbour A. G. 1994. A family of surface-exposed proteins of 20 kilodaltons in the genus Borrelia. Infect. Immun. 62:2792–2799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eicken C., et al. 2001. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein C from Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10010–10015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eng J. A., McCormack A. L., Yates J. R., III 1994. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5:976–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frank K. L., Bundle S. F., Kresge M. E., Eggers C. H., Samuels D. S. 2003. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 185:6723–6727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grimm D., et al. 2004. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3142–3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hossain H., Wellensiek H. J., Geyer R., Lochnit G. 2001. Structural analysis of glycolipids from Borrelia burgdorferi. Biochimie 83:683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones J. D., Bourell K. W., Norgard M. V., Radolf J. D. 1995. Membrane topology of Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 63:2424–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaiser R., Metzka L. 1999. Enhancement of cyanogen bromide cleavage yields for methionyl-serine and methionyl-threonine peptide bonds. Anal. Biochem. 266:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim D. Y., Kim K. K. 2005. Structure and function of HtrA family proteins, the key players in protein quality control. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38:266–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kudryashev M., et al. 2009. Comparative cryo-electron tomography of pathogenic Lyme disease spirochetes. Mol. Microbiol. 71:1415–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumaran D., et al. 2001. Crystal structure of outer surface protein C (OspC) from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 20:971–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumru O. S., Schulze R. J., Rodnin M. V., Ladokhin A. S., Zückert W. R. 2011. Surface localization determinants of Borrelia OspC/Vsp family lipoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 193:2814–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Labandeira-Rey M., Skare J. T. 2001. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect. Immun. 69:446–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lawson C. L., Yung B. H., Barbour A. G., Zückert W. R. 2006. Crystal structure of neurotropism-associated variable surface protein 1 (Vsp1) of Borrelia turicatae. J. Bacteriol. 188:4522–4530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin B., Short S. A., Eskildsen M., Klempner M. S., Hu L. T. 2001. Functional testing of putative oligopeptide permease (Opp) proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi: a complementation model in opp(-) Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1499:222–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Magnarelli L. A., Anderson J. F., Barbour A. G. 1989. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for Lyme disease: reactivity of subunits of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Infect. Dis. 159:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mbow M. L., Gilmore R. D. J., Titus R. G. 1999. An OspC-specific monoclonal antibody passively protects mice from tick-transmitted infection by Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 67:5470–5472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Motaleb M. A., et al. 2000. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10899–10904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nally J. E., Timoney J. F., Stevenson B. 2001. Temperature-regulated protein synthesis by Leptospira interrogans. Infect. Immun. 69:400–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nilsson C. L., et al. 2002. Characterization of the P13 membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi by mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 13:295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Noppa L., Östberg Y., Lavrinovicha M., Bergström S. 2001. P13, an integral membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi, is C-terminally processed and contains surface-exposed domains. Infect. Immun. 69:3323–3334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Östberg Y., et al. 2004. Pleiotropic effects of inactivating a carboxyl-terminal protease, CtpA, in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 186:2074–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Östberg Y., Pinne M., Benz R., Rosa P., Bergström S. 2002. Elimination of channel-forming activity by insertional inactivation of the p13 gene in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 184:6811–6819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pinne M., Östberg Y., Comstedt P., Bergström S. 2004. Molecular analysis of the channel-forming protein P13 and its paralogue family 48 from different Lyme disease Borrelia species. Microbiology 150:549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pinne M., et al. 2007. Elimination of channel-forming activity by insertional inactivation of the p66 gene in Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266:241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Purser J. E., Norris S. J. 2000. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:13865–13870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Radolf J. D., Bourell K. W., Akins D. R., Brusca J. S., Norgard M. V. 1994. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi membrane architecture by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 176:21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramamoorthi N., et al. 2005. The Lyme disease agent exploits a tick protein to infect the mammalian host. Nature 436:573–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sadziene A., Thomas D. D., Barbour A. G. 1995. Borrelia burgdorferi mutant lacking Osp: biological and immunological characterization. Infect. Immun. 63:1573–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sambrook J., Russell D. W. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 47. Samuels D. S. 1995. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schroeder W. A., Shelton J. B., Shelton J. R. 1969. An examination of conditions for the cleavage of polypeptide chains with cyanogen bromide: application to catalase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 130:551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schulze R. J., Chen S., Kumru O. S., Zückert W. R. 2010. Translocation of Borrelia burgdorferi surface lipoprotein OspA through the outer membrane requires an unfolded conformation and can initiate at the C terminus. Mol. Microbiol. 76:1266–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schulze R. J., Zückert W. R. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins are secreted to the outer surface by default. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1473–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Skare J. T., et al. 1997. The Oms66 (p66) protein is a Borrelia burgdorferi porin. Infect. Immun. 65:3654–3661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stewart P. E., Thalken R., Bono J. L., Rosa P. 2001. Isolation of a circular plasmid region sufficient for autonomous replication and transformation of infectious Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 39:714–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stewart P. E., et al. 2006. Delineating the requirement for the Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factor OspC in the mammalian host. Infect. Immun. 74:3547–3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takayama K., Rothenberg R. J., Barbour A. G. 1987. Absence of lipopolysaccharide in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 55:2311–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tilly K., et al. 2006. Borrelia burgdorferi OspC protein required exclusively in a crucial early stage of mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 74:3554–3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Walker E. M., Borenstein L. A., Blanco D. R., Miller J. N., Lovett M. A. 1991. Analysis of outer membrane ultrastructure of pathogenic Treponema and Borrelia species by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 173:5585–5588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang X. G., et al. 2004. Analysis of differences in the functional properties of the substrate binding proteins of the Borrelia burgdorferi oligopeptide permease (Opp) operon. J. Bacteriol. 186:51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xu H., Freitas M. A. 2009. MassMatrix: a database search program for rapid characterization of proteins and peptides from tandem mass spectrometry data. Proteomics 9:1548–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zückert W. R. 2007. Laboratory maintenance of Borrelia burgdorferi. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 12, Unit 12C.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]