Abstract

The cell wall-less prokaryote Mycoplasma pneumoniae causes bronchitis and atypical pneumonia in humans. Mycoplasma attachment to the host respiratory epithelium is required for colonization and mediated largely by a differentiated terminal organelle. P30 is an integral membrane protein located at the distal end of the terminal organelle. The P30 null mutant II-3 is unable to attach to host cells and nonmotile and has a branched cellular morphology compared to the wild type, indicating an important role for P30 in M. pneumoniae biology. P30 is predicted to have an N-terminal signal sequence, but the presence of such a motif has not been confirmed experimentally. In the current study we analyzed P30 derivatives having epitope tags engineered at various locations to demonstrate that posttranslational processing occurred in P30. Several potential cleavage sites predicted in silico were examined, and a processing-defective mutant was created to explore P30 maturation further. Our results suggested that signal peptide cleavage occurs between residues 52 and 53 to yield mature P30. The processing-defective mutant exhibited reduced gliding velocity and cytadherence, indicating that processing is required for fully functional maturation of P30. We speculate that P30 processing may trigger a conformational change in the extracellular domain or expose a binding site on the cytoplasmic domain to allow interaction with a binding partner as a part of functional maturation.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an important etiologic agent of community-acquired tracheobronchitis and pneumonia in humans. This cell wall-less prokaryote causes respiratory disease in persons of all ages but especially older children and young adults, and a strong correlation exists between M. pneumoniae infections and onset and exacerbation of asthma (3, 27, 29, 36). Adherence to the respiratory epithelium is essential for colonization and virulence (21) and is mediated largely by the terminal organelle (5, 28), a polar, differentiated, membrane-bound extension of the mycoplasma cell having a complex electron-dense core capped by a terminal button at the distal end (2, 15). The terminal organelle is also the motor for gliding motility (11), and its duplication precedes cell division (12). Studies have identified several key terminal organelle components, the loss of which impacts cytadherence, motility, and cell division (11, 13, 21).

P30 is an integral membrane protein that localizes to the distal end of the terminal organelle (1, 6, 7). Loss of P30 due to a frameshift in its corresponding gene (MPN453) results in the inability to cytadhere or glide and a branched cellular morphology (30). Complementation with the corresponding recombinant wild-type allele restores a wild-type phenotype (30). The deduced N terminus of P30 is positively charged with five basic residues, which are followed by a 23-residue hydrophobic region, and is thought to comprise a signal peptide (6, 7) (Fig. 1A). However, deletion of a region downstream of this putative signal peptide (residues 38 to 68) generates a P30 derivative (P30ΔI) which actually migrates higher than wild-type P30 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that processing for P30 maturation occurs further downstream than originally thought, within the deleted region in P30ΔI (4). Given its distinctive trafficking to the distal end of the terminal organelle, we sought to explore whether P30 processing plays a role in localization and functional maturation. Here we engineered epitope tags at different positions in P30 to localize the processing site, and G substitutions at putative −1 and −3 residues to define that site more precisely. Substitutions at L50, V52, and V53 resulted in a processing-defective mutant (designated pre-P30), which we assessed for its capacity to rescue cytadherence, gliding motility, and normal cell division in the P30 null mutant II-3. Recombinant pre-P30 localized normally to the distal end of the terminal organelle but failed to restore fully wild-type gliding motility and cytadherence, suggesting that processing was required for full function.

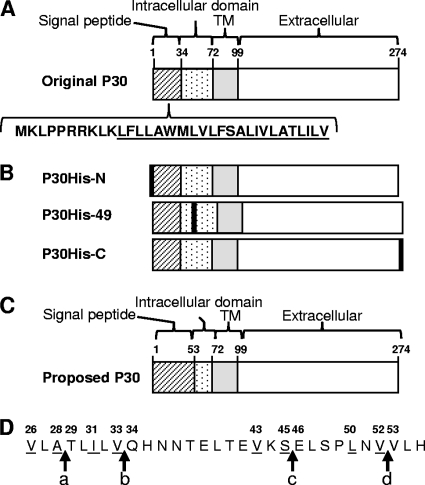

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic of wild-type P30 based upon the originally predicted signal peptide, including the deduced amino acid sequence of the signal peptide predicted based upon its hydropathy plot (4); underlined type, predicted hydrophobic core; TM, transmembrane domain. (B) Schematic of P30His derivatives; black boxes, His6 tag. (C) Schematic of proposed P30 based upon this study. (D) P30 deduced amino acid sequence for residues 26 to 53; arrows, potential cleavage sites: a, predicted site by SignalP (NN); b, original model based upon hydropathy plot; c, predicted site by SignalP (HMM); d, predicted site by molecular mass; underlined letters, G substitutions generated. Numbers in all panels correspond to amino acid residues from N terminus.

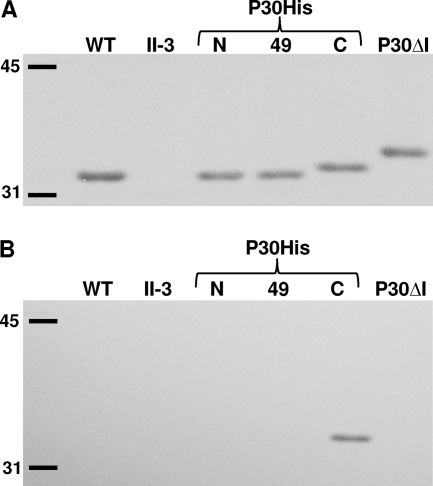

Fig. 2.

Western immunoblot analysis of P30 from wild-type M. pneumoniae (WT), mutant II-3, the indicated P30His derivatives, and P30ΔI (4), with anti-P30 (A) or anti-poly-His (B) antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma strains and construction of P30 derivatives.

Wild-type M. pneumoniae strain M129 (17th broth passage) (25) and the spontaneously arising noncytadherent P30 null mutant II-3 (21) were grown in SP4 medium (4, 21), with gentamicin (18 μg/ml) included as appropriate for culture of transformants. Plasmids used in the current study are described in Table 1. The recombinant transposon containing the wild-type P30 allele and the promoter region upstream was described previously (pKV75) (4, 14, 30). The P30His-C, P30His-N, P30His-49, and P30 cleavage site derivatives were engineered by PCR mutagenesis using pKV75 as a template (4) and primers indicated in Table 2, cloning the PCR products for each into pKV74 (14) or pMT85. We created pKV424 and pKV425 in the same manner but used pKV399 as a template (Table 1). To place P30 synthesis under the control of the tuf promoter, we used pKV344 as a template with primer pair 1 and pKV75 as a template with primer pair 2.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| pKV74 | Tn4001 derivative | 4, 14 |

| pKV75 | Tn4001 containing alleles from EcoRI fragment of hmw locus (548109 to 557495) | 4 |

| pMT85 | Tn4001 minitransposon derivative | 12, 14 |

| pKV344 | Tn4001 containing tuf promoter | 18, this study |

| pKV451 | pMT85 + P30His-N | This study |

| pKV449 | pMT85 + P30His-49 | This study |

| pKV245 | pKV74 + P30His-C | This study |

| pKV381 | pMT85 + P30V26GA28G | This study |

| pKV382 | pMT85 + P30I31GV33G | This study |

| pKV383 | pMT85 + P30V43GS45G | This study |

| pKV384 | pMT85 + P30L50GV52G | This study |

| pVK398 | pMT85 + P30L50GN51GV52G | This study |

| pKV399 | pMT85 + P30L50GV52GV53G | This study |

| pKV424 | pMT85 + P30L50GV52GV53G-His-N | This study |

| pKV425 | pMT85 + Tuf-P30-L50GV52GV53G | This study |

Table 2.

Primers used in creating P30 derivativesa

| Strain | Plasmid | Primer pair 1 (5′-3′) | Primer pair 2 (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P30His-C | pKV245 | GTAGCTTCATGAATTCGGTCT | NA |

| GGATCCTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGCGTTTTGGTGG | |||

| P30His-N | pKV448 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | CATCACCATCACCATCACAAGTTACCACCTCGAA |

| GATGGTGATGGTGATGCATGCACTAATTAAAGGG | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30His-49 | pKV449 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | CATCACCATCACCATCACCTTAACGTTGTTTTAC |

| GTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGGGACTCAATT | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30V26GA28G | pKV381 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | GCTTTAATAGGTCTTGGCACCTTAATTTT |

| AAAATTAAGGTGCCAAGACCTATTAAAGC | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30I31GV33G | pKV382 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | AACCTTAGGTTTGGGTCAGCACAA |

| TTGTGCTGACCCAAACCTAAGGTT | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30V43GS45G | pKV383 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | TGACAGAAGGTAAGGGTGAATTGA |

| TCAATTCACCCTTACCTTCTGTCA | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30L50GV52G | pKV384 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | TTGAGTCCCGGTAACGGTGTTTTA |

| TAAAACACCGTTACCGGGACTCAA | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30L50GN51GV52G | pVK398 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | GAGTCCCGGTGGCGGTGTTTTA |

| ACCGCCACCGGGACTCAATT | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30L50GV52GV53G | pKV399 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | TAACGGTGGTTTACACGCAGAAGA |

| CACCGTTACCGGGACTCAATTCAC | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| P30His-N-L50GV52GV53G | pKV424 | GCTTCATGAACTGGATCCACTTTAT | CATCACCATCACCATCACAAGTTACCACCTCGAA |

| GATGGTGATGGTGATGCATGCACTAATTAAAGGG | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA | ||

| Tuf-P30-L50GV52GV53G | pKV425 | ACACACACTAGTACGGATCC | TTCAAACACATGAAGTTACCACC |

| GGTAACTTCATGTGTTTGAATTACG | CCCGGTTTCAGAATTCTGGTACA |

Italicized nucleotides, modified bases from MPN453; bold nucleotides, bases encoding His6; underlined nucleotides, EcoRI sites; double underlined nucleotides, BamHI sites; NA, not applicable.

Western immunoblotting.

Samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (24) and Western immunoblotting (33) using standard protocols with minor modifications (4). Mouse monoclonal P30-specific antibodies against the C terminus were used at 1:1,000 (6, 26), rabbit polyclonal anti-His antibodies were used at 1:5,000 (Immunology Consultants Laboratories; Newberg, OR), and rabbit polyclonal anti-P65 antiserum was used at 1:5,000 (4).

Microscopy and gliding motility.

Mycoplasmas were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy with mouse monoclonal anti-P30 antibody at 1:50 and rabbit polyclonal anti-HMW1 antiserum at 1:1,000 (4). Images were captured with OpenLab Imaging Software version 5.01 (v5.01) (Improvision, Lexington, MA) and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS3 v10 (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA) (14). For motility studies, mycoplasmas were grown at 37°C in borosilicate glass chamber slides (Nunc Nalgene, Naperville, IL) containing SP4 medium plus 3% gelatin, with or without gentamicin. Colony morphology was examined at 24-h intervals for satellite growth as a qualitative indicator of gliding motility, and over 18 h for quantitative assessment of motility (14). A minimum of 60 cells per strain were observed to determine gliding velocity. Mean and corrected mean gliding velocities were calculated as described previously (14).

Cytadherence.

Assessment of mycoplasma binding to erythrocytes (hemadsorption [HA]) is a convenient indicator of cytadherence (31) and for qualitative HA was performed as previously described, using sheep blood (20). For quantitative HA (qHA) (10, 19), radiolabeled mycoplasmas were incubated with a 4% suspension of chicken blood cells in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C for 30 min, loaded onto a 40% sucrose cushion, and centrifuged for 20 s at 1,690 × g. The blood cell pellet was collected, lysed with 1% SDS, and processed for liquid scintillation counting.

Colonization of NHBE cells.

Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells (Cambrex, San Diego, CA) were cultured, and mycoplasma colonization was assayed as described previously (17, 23). Briefly, NHBE cells seeded into individual Transwell supports (Costar, Cambridge, MA) coated with rat-tail collagen type I (Collaborative Research, Bedford, MA) were fed apically and basally for 5 to 7 days and then only basally for 4 to 6 weeks or until used. Mycoplasma cells were grown in SP4 with [3H]thymidine, harvested, and kept on the ice. Prior to infection, NHBE cells were washed with prewarmed Hanks balanced salt solution (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) to remove excess mucus. Radiolabeled mycoplasmas were incubated with NHBE cells apically at 37°C for 4 h, after which the NHBE cells were washed four times with PBS and dried overnight. Membranes carrying the NHBE cells were then removed from the Transwell supports, treated with 1% SDS and processed for liquid scintillation counting. Each strain was examined in triplicate or quadruplicate, and binding assays were carried out at least twice.

RESULTS

Evidence of a P30 signal sequence.

P30 was originally predicted to be a transmembrane protein having an N-terminal signal peptide (6) (Fig. 1A), but this has not previously been tested directly, and some algorithms predict two membrane-spanning domains and no precursor processing for P30 (data not shown). Recent domain deletion studies suggest that P30 processing indeed occurs, but at a site well downstream of the original prediction (4). Given its unusual compartmentalization to the distal end of the terminal organelle and the potential role a large leader peptide might play in trafficking, we examined P30 processing here in more detail. We engineered His6 epitope tags at the N terminus immediately after the predicted initiation codon (P30His6-N), after residue P49 within the predicted cytoplasmic domain (P30His6-49), and at the C terminus (P30His6-C) (Fig. 1B), and introduced each into P30 null mutant II-3 by transposon delivery as described previously (14, 30). Multiple transformants were examined for each to control for potential positional effects associated with transposon insertion. Each P30His6 derivative was detected at near-wild-type levels by immunoblotting when probed with P30-specific antibodies (Fig. 2A). P30His6-C consistently migrated slightly higher than wild-type P30, whereas P30His6-N and P30His6-49 comigrated with wild-type P30 (Fig. 2A). However, only P30His6-C was detected when parallel samples were probed with poly-His-specific antibodies (Fig. 2B), indicating the likely removal of the epitope tag for P30His6-N and P30His6-49. These transformants each exhibited wild-type phenotypes with respect to P30 localization, cytadherence, and gliding motility (data not shown).

Mutagenesis screening of potential cleavage sites.

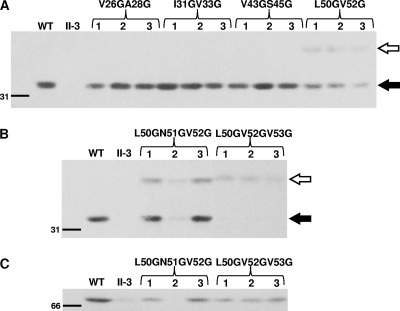

A hydrophobicity plot analysis (http://www.bmm.icnet.uk/∼offman01/hydro.html) placed the cleavage site of the putative signal sequence in the current P30 model between V33 and Q34 (Fig. 1D, arrow b). In contrast, the program SignalP 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) placed the cleavage site between residues A28 and L29 using neural networks (NN) and residue S45 and E46 using a hidden Markov model (HMM) (Fig. 1D, arrows a and c, respectively). However, our P30His6-49 data suggested that cleavage occurs after residue P49, and in order to fulfill that prerequisite, we predicted an alternative cleavage site based on the difference in molecular masses between P30ΔI and wild-type P30 and the assumption that P30ΔI, which lacks residues 38 to 68 of P30, migrates higher than its predicted mass (4) (Fig. 2A) due to loss of the processing site and retention of the signal sequence. Processing based on this prediction would occur between residues V52 and V53 (Fig. 1D, arrow d). Given the highly conserved nature of bacterial signal peptide cleavage sites (34), these four potential sites were analyzed further by engineering G substitutions at the −1 and −3 positions for each and introducing the resulting P30 derivatives (P30-V26GA28G, P30-I31GV33G, P30-V43GS45G, and P30-L50GV52G) individually into mutant II-3 for evaluation of stability and size by Western immunoblotting. All but P30-L50GV52G were identical to wild-type P30 in stability and migration (Fig. 3A). Two bands were observed for P30-L50GV52G, a faint band at 40 kDa and a darker band at 32 kDa, the latter corresponding to mature wild-type P30 (Fig. 3A). Transformants for all four derivatives exhibited a wild-type phenotype with respect to protein localization, cytadherence, and gliding motility, indicating functional P30 capable of rescuing the II-3 defect (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Western immunoblot analysis of representative mutant II-3 transformants with double- (A) and triple- (B and C) substitution P30 derivatives. Transformants shown in panels A and B were probed with P30-specific antibodies, and those shown in panel C with P65-specific antibodies. Three transformants are shown for each derivative. Open arrow, pre-P30; solid arrow, mature P30. Size standard is indicated on the left in kDa.

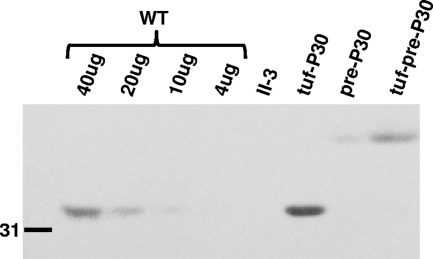

Engineering and analysis of a P30 processing mutant.

Two P30 derivatives were engineered to have triple substitutions at potentially important residues for processing (P30-L50GN51GV52G and P30-L50GV52GV53G) in order to generate an unprocessed P30 derivative. P30-L50GN51GV52G exhibited by Western immunoblotting a pattern similar to that of P30-L50GV52G but with a more intense putative precursor band, whereas P30-L50GV52GV53G exhibited only the putative P30 precursor (Fig. 3B). As P30-L50GV52GV53G yielded only preprocessed P30, we refer to this derivative henceforth as pre-P30. Pre-P30 was observed at lower steady-state levels than wild-type P30 in Western immunoblots. By comparing band intensities with decreasing quantities of wild-type M. pneumoniae, we determined that pre-P30 was present at a level 25% of that of the wild type (Fig. 4). Pre-P30 localized normally, i.e., distal to HMW1 at the terminal organelle, despite its reduced stability and failure to process (Fig. 5). However, the levels of protein P65, which requires P30 for stabilization, were not fully restored to wild-type levels in these transformants (Fig. 3C). We also engineered pre-P30 with an N-terminal His6 epitope tag and examined its subcellular localization. Normal immunofluorescence labeling was observed with anti-P30 antibodies, but somewhat surprisingly, not with tag-specific antibodies, even though the latter readily detected this P30 derivative in Western immunoblots (data not shown), suggesting that the tag was antibody inaccessible, even with cell permeabilization for immunofluorescence analysis. Despite its normal localization, pre-P30 nevertheless failed to fully rescue gliding motility in mutant II-3 transformants, which exhibited a gliding velocity of <10% of that of the wild type (Table 3). II-3+pre-P30 was likewise defective in cytadherence based both on qualitative HA, where erythrocyte binding was intermediate (data not shown), and qHA, where adherence was only <50% of that of the wild type (Fig. 6A). Finally, mutant II-3+pre-P30 colonized differentiated NHBE cells in air-liquid interface culture at only 4% of wild-type levels (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative assessment of P30 levels in wild-type M. pneumoniae (WT) and the indicated P30 derivatives by Western immunoblotting analysis. Total protein loaded: WT as indicated; all others, 40 μg. Size standard is shown on the left in kDa.

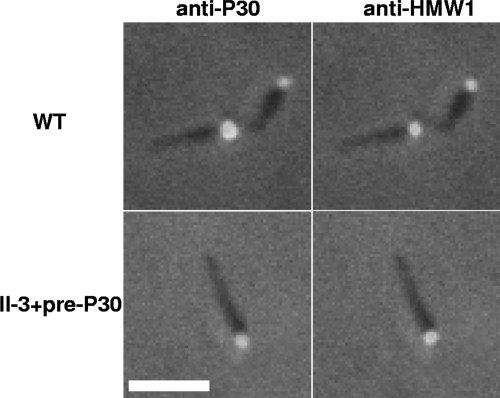

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence localization of P30 (left) and HMW1 (right) in wild-type M. pneumoniae (WT) and mutant II-3+pre-P30. Merged fluorescence and phase contrast images of individual cells are shown. Scale bar: 2 μm.

Table 3.

Cell gliding velocity for wild-type M. pneumoniae and representative transformants of mutant II-3+pre-P30 or II-3+tuf-pre-P30a

| Strain | No. of cells | Mean gliding velocity μm s−1 ± SEM (% WT) | Mean corrected gliding velocity μm s−1 ± SEM (% WT)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 100 | 0.2726 ± 0.0147 (100) | 0.3191 ± 0.0134 (10) |

| II-3 | 0 | 0 | |

| II-3+pre-P30-1 | 66 | 0.0112 ± 0.0015 (4.1) | 0.0178 ± 0.0015 (5.6) |

| II-3+pre-P30-2 | 62 | 0.0176 ± 0.0026 (6.4) | 0.0250 ± 0.0026 (7.8) |

| II-3+tuf-pre-P30-1 | 100 | 0.0156 ± 0.0030 (5.7) | 0.0216 ± 0.0017 (6.8) |

| II-3+tuf-pre-P30-2 | 100 | 0.0211 ± 0.0044 (7.7) | 0.0250 ± 0.0022 (7.8) |

SEM, standard error of the mean.

Mean corrected gliding velocity=total distance traveled by a cell/total time of the field interval less time spent in resting periods (14).

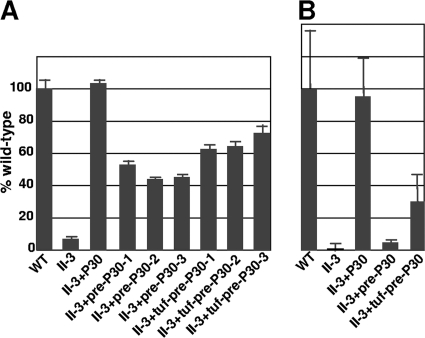

Fig. 6.

Quantitative analysis of HA (A) and NHBE cell colonization (B) by wild-type M. pneumoniae (WT), mutant II-3, and II-3 transformants with the indicated P30 derivatives. Values are normalized to that for wild-type M. pneumoniae. Three different transformants each for II-3+pre-P30 and II-3+tuf-pre-P30 were analyzed for HA, while one of each was examined further with NHBE cells. Bars indicate means and standard errors of the means of results from duplicate or triplicate assays.

To assess if the reduced function was due to the lower steady-state levels of pre-P30, we engineered this derivative under the control of the tuf promoter (tuf-pre-P30) for enhanced expression (18). This resulted in pre-P30 levels more similar to that of wild-type P30, with no mature P30 detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 4), and restored P65 levels (data now shown). The increased levels of pre-P30 in II-3 transformants with tuf-pre-P30 failed to restore gliding velocities (Table 3) and resulted in only modest increases in HA and NHBE cell colonization (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

The N terminus of P30 exhibits typical features of a type I signal peptide, and our analysis of P30 deletion derivatives provides evidence of P30 processing (4). Results here from the characterization of P30 derivatives engineered with a His6 epitope tag at various locations were consistent with that conclusion, although the inability to detect a P30 precursor in wild-type M. pneumoniae by immunoblotting suggests that processing occurs quickly. To further define P30 processing, four possible cleavage sites were modified by introducing G substitutions at the −1 and −3 positions for each in order to disrupt signal peptide removal. The results demonstrated that residues L50, V52, and V53 are involved in precursor processing, and we propose that mature P30 starts at residue V53, with processing removing approximately 20% of pre-P30 (Fig. 1C). To determine if this putative 52-residue P30 leader peptide was stable and might serve a function beyond membrane targeting, we probed M. pneumoniae P30His-N with anti-His antibody but failed to detect the peptide by either Western immunoblotting or immunofluorescence analysis (data not shown), suggesting that it is not retained but perhaps targeted by a signal peptide peptidase.

The reason for a long signal peptide for P30 is unknown, but it seems noteworthy that the major adhesin protein P1, also an integral membrane protein that localizes primarily to the terminal organelle, has a signal peptide of similar length (32). The N terminus of P1, like that of P30, has a typical signal peptidase I-like cleavage site, i.e., positive charged residues followed by a hydrophobic core and ending with A at predicted −1 and −3 positions (32, 35). However, the N terminus of mature P1 has been shown experimentally to be residue N60, which is 36 residues downstream of the predicted signal peptidase cleavage site (22). Despite their similarity in signal peptide features, P1 and P30 lack sequence homology in the region spanning from the end of their hydrophobic cores to their processing sites. Perhaps significantly, M. pneumoniae has many core components of the conserved Sec secretion machinery but lacks the gene for type I signal peptidase (9). Dandekar et al. proposed the MPN386 product as an alternative to type I signal peptidase (8), which might account for apparently atypical processing. We cannot exclude the possibility of two-step processing of P30, with a true signal peptide removed by a signal peptidase, followed by a second proteolytic event to yield the mature protein. However, such a model is not supported by results with G substitutions at the potential signal peptidase cleavage sites tested (this study) or by the analysis of deletion derivatives (4). Regardless, the size of the recombinant P30 homolog in Mycoplasma genitalium (P32) produced in M. pneumoniae mutant II-3 indicates processing (M. Balish, personal communication), and comparison of their deduced sequences reveals significant sequence conservation, including the LXVV motif at the putative P30 cleavage site (Fig. 7), consistent with our conclusion here regarding P30 maturation.

Fig. 7.

BOXSHADE analysis of the N terminus of M. pneumoniae protein P30 and M. genitalium protein P32. Black and gray blocks, identical and similar amino acids, respectively; underlined letters, LXVV motif. The alignment of sequences was analyzed by the ClustalW2 program at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ and box shaded by BOXSHADE 3.21 at http://www.ch.embnet.org.

Pre-P30 localized correctly to the terminal organelle yet failed to confer full gliding and cytadherence function or the capacity to colonize fully differentiated NHBE cells in air-liquid interface culture. Colonization of differentiated NHBE cells is thought to place a premium on combined adherence and gliding capabilities for M. pneumoniae to overcome the mucocilliary barrier and gain access to and bind receptors on the host cell surface. Increased production of pre-P30 from the tuf promoter failed to increase gliding velocity and only modestly increased cytadherence, suggesting that failure to process P30 was responsible for loss of function. We recently demonstrated that the putative cytoplasmic domain of P30 is also required for normal cytadherence and gliding (4), and in that context at least two scenarios might account for defective pre-P30 function in adherence and gliding. First, P30 processing may be required to trigger an essential conformational change in the extracellular domain. Alternatively, or perhaps in addition, the retained pre-P30 signal peptide might obscure interaction with an intracellular binding partner. Regarding the latter, we suggested previously that the P30 intracellular domain may link P30 to the terminal organelle core (4), based upon electron cryotomography images in which rows of proteins on the inner surface of the membrane appear to link the mycoplasma cytoskeleton to surface structures at the distal end of the terminal organelle (16).

In summary, our data establish that P30 is produced as a precursor that is processed rapidly to yield the mature protein. The pre-P30 generated by mutating the putative processing site appeared to be less stable than wild-type P30 yet localized to the terminal organelle. Pre-P30, even when present at near-wild-type steady-state levels, did not fully rescue cellular motility or cytadherence, indicating that processing is required for functional maturation. What role, if any, the leader peptide may play in P30 maturation is not known, but if P30 undergoes final folding to a functional adhesin only after localizing to the terminal organelle, then the leader peptide may prevent premature folding or interaction with binding partners until proper localization is realized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Balish for sharing unpublished data.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI23362 and AI49194 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to D.C.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baseman J. B., et al. 1987. Identification of a 32-kilodalton protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with hemadsorption. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 23:474–479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biberfeld G., Biberfeld P. 1970. Ultrastructural features of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 102:855–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Biscardi S., et al. 2004. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and asthma in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:1341–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang H., Jordan J. L., Krause D. C. 2011. Domain analysis of protein P30 in Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence and gliding motility. J. Bacteriol. 193:1726–1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collier A. M., Clyde W. A., Jr., Denny F. W. 1971. Mycoplasma pneumoniae in hamster tracheal organ culture: immunofluorescent and electron microscopic studies. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 136:569–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dallo S. F., Chavoya A., Baseman J. B. 1990. Characterization of the gene for a 30-kilodalton adhesion-related protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 58:4163–4165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dallo S. F., Lazzell A. L., Chavoya A., Reddy S. P., Baseman J. B. 1996. Biofunctional domains of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae P30 adhesin. Infect. Immun. 64:2595–2601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dandekar T., et al. 2000. Re-annotating the Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome sequence: adding value, function and reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3278–3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edman M., Jarhede T., Sjostrom M., Wieslander A. 1999. Different sequence patterns in signal peptides from mycoplasmas, other gram-positive bacteria, and Escherichia coli: a multivariate data analysis. Proteins 35:195–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisseha M., Gohlmann H. W., Herrmann R., Krause D. C. 1999. Identification and complementation of frameshift mutations associated with loss of cytadherence in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 181:4404–4410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hasselbring B. M., Krause D. C. 2007. Cytoskeletal protein P41 is required to anchor the terminal organelle of the wall-less prokaryote Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 63:44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hasselbring B. M., Jordan J. L., Krause R. W., Krause D. C. 2006. Terminal organelle development in the cell wall-less bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16478–16483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasselbring B. M., Page C. A., Sheppard E. S., Krause D. C. 2006. Transposon mutagenesis identifies genes associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae gliding motility. J. Bacteriol. 188:6335–6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hasselbring B. M., Jordan J. L., Krause D. C. 2005. Mutant analysis reveals a specific requirement for protein P30 in Mycoplasma pneumoniae gliding motility. J. Bacteriol. 187:6281–6289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hegermann J., Herrmann R., Mayer F. 2002. Cytoskeletal elements in the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Naturwissenschaften 89:453–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henderson G. P., Jensen G. J. 2006. Three-dimensional structure of Mycoplasma pneumoniae's attachment organelle and a model for its role in gliding motility. Mol. Microbiol. 60:376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jordan J. L., et al. 2007. Protein P200 is dispensable for Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemadsorption but not gliding motility or colonization of differentiated bronchial epithelium. Infect. Immun. 75:518–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kenri T., et al. 2004. Use of fluorescent-protein tagging to determine the subcellular localization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins encoded by the cytadherence regulatory locus. J. Bacteriol. 186:6944–6955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krause D. C., Leith D. K., Baseman J. B. 1983. Reacquisition of specific proteins confers virulence in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 39:830–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krause D. C., Baseman J. B. 1982. Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins that selectively bind to host cells. Infect. Immun. 37:382–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krause D. C., Leith D. K., Wilson R. M., Baseman J. B. 1982. Identification of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins associated with hemadsorption and virulence. Infect. Immun. 35:809–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Krause D. C., Balish M. F. 2001. Structure, function, and assembly of the terminal organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krunkosky T. M., Jordan J. L., Chambers E., Krause D. C. 2007. Mycoplasma pneumoniae host-pathogen studies in an air-liquid culture of differentiated human airway epithelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 42:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laemmli U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lipman R. P., Clyde W. A., Jr 1969. The interrelationship of virulence, cytadsorption, and peroxide formation in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 131:1163–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morrison-Plummer J., Leith D. K., Baseman J. B. 1986. Biological effects of anti-lipid and anti-protein monoclonal antibodies on Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 53:398–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park S. J., Lee Y. C., Rhee Y. K., Lee H. B. 2005. Seroprevalence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in stable asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Korean Med. Sci. 20:225–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Powell D. A., Hu P. C., Wilson M., Collier A. M., Baseman J. B. 1976. Attachment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae to respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 13:959–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Razin S., Jacobs E. 1992. Mycoplasma adhesion. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:407–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Romero-Arroyo C. E., et al. 1999. Mycoplasma pneumoniae protein P30 is required for cytadherence and associated with proper cell development. J. Bacteriol. 181:1079–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sobeslavsky O., Prescott B., Chanock R. M. 1968. Adsorption of Mycoplasma pneumoniae to neuraminic acid receptors of various cells and possible role in virulence. J. Bacteriol. 96:695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Su C. J., Tryon V. V., Baseman J. B. 1987. Cloning and sequence analysis of cytadhesin P1 gene from Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 55:3023–3029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:4350–4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tuteja R. 2005. Type I signal peptidase: an overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 441:107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Roosmalen M. L., et al. 2004. Type I signal peptidases of Gram-positive bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694:279–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Waites K. B., Talkington D. F. 2004. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:697–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]