Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of death in children worldwide and forms highly organized biofilms in the nasopharynx, lungs, and middle ear mucosa. The luxS-controlled quorum-sensing (QS) system has recently been implicated in virulence and persistence in the nasopharynx, but its role in biofilms has not been studied. Here we show that this QS system plays a major role in the control of S. pneumoniae biofilm formation. Our results demonstrate that the luxS gene is contained by invasive isolates and normal-flora strains in a region that contains genes involved in division and cell wall biosynthesis. The luxS gene was maximally transcribed, as a monocistronic message, in the early mid-log phase of growth, and this coincides with the appearance of early biofilms. Demonstrating the role of the LuxS system in regulating S. pneumoniae biofilms, at 24 h postinoculation, two different D39ΔluxS mutants produced ∼80% less biofilm biomass than wild-type (WT) strain D39 did. Complementation of these strains with luxS, either in a plasmid or integrated as a single copy in the genome, restored their biofilm level to that of the WT. Moreover, a soluble factor secreted by WT strain D39 or purified AI-2 restored the biofilm phenotype of D39ΔluxS. Our results also demonstrate that during the early mid-log phase of growth, LuxS regulates the transcript levels of lytA, which encodes an autolysin previously implicated in biofilms, and also the transcript levels of ply, which encodes the pneumococcal pneumolysin. In conclusion, the luxS-controlled QS system is a key regulator of early biofilm formation by S. pneumoniae strain D39.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) is a Gram-positive pathogen that causes severe illnesses such as otitis media, pneumonia, and meningitis mainly in young children (<5 years old), immunocompromised patients, and the elderly (20, 25, 53). The pneumococcus colonizes the mucosal surface of the upper respiratory tract, the nasopharynx, in early childhood (22, 51). After colonization, this bacterium can cause disease and be rapidly transmitted to other children by coughing or may persist for months, thereby maintaining noninvasive strains in the human population (53). Colonization of the nasopharynx and persistence are important risk factors for both pneumococcal disease and carriage (20, 22).

The mechanism by which S. pneumoniae strains colonize and persist in the nasopharynx is still incompletely understood. During this transition, however, pneumococci must be able to adapt to their new niche by competing against other pneumococci, as well as other native flora, and evade the host immune response. Recently, the persistence of opportunistic pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae, Bordetella, or Moraxella catarrhalis, at different anatomic sites has been linked to highly specialized biofilms (3, 45, 47).

All of the S. pneumoniae strains investigated so far, whether they are invasive isolates or normal-flora strains, are capable of producing biofilms in vitro (2, 11, 13, 28, 34). More importantly, S. pneumoniae biofilms have been detected on the surface of adenoid and mucosal epithelial cells from biopsy specimens collected from children with chronic otitis media (16). Further studies with a chinchilla model support a role for biofilms in pneumococcal otitis media (56). While such structures have not been studied or described in patients with pneumonia, detailed work by Sanchez et al. (44) demonstrated that a virulent S. pneumoniae strain produced biofilms in the nasopharynx, trachea, and lungs of mice experimentally infected with strain TIGR4. Biofilms may also contribute to the increasing rates of antibiotic resistance among S. pneumoniae strains. For example, in vitro studies show that S. pneumoniae biofilms, in comparison to their planktonic cultures, have a profile of increased resistance to all of the classes of oral antibiotics widely used to treat pneumococcal infections, namely, β-lactams, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones (11, 13).

Several molecular factors, including virulence factors, have been implicated in S. pneumoniae biofilm formation. Studies by Moscoso et al. (32) found that the amidases LytA, LytC, and LytB and adhesins such as CbpA, PcpA, and PspA play some role in S. pneumoniae biofilms. Another study by Muñoz-Elías et al. (34) identified 23 genes (encoding adhesins, choline binding proteins, and cell wall components) implicated in biofilm formation and colonization in a mouse model. Two other important virulence factors implicated in the production of biofilms are PsrP (44) and the neuraminidase NanA (40). While it is clear that all of these factors may play a role in the development of the biofilm structure, the specific mechanism by which S. pneumoniae biofilms are built remains to be elucidated.

Biofilm formation requires a concerted mechanism regulated, in part, by numerous environmental signals (24). In S. intermedius, S. oralis, S. gordonii, and S. mutans strains, regulation of biofilm formation has been linked to LuxS (1, 7, 31, 42), an enzyme that synthesizes autoinducer 2 (AI-2), which is required for quorum sensing (QS). The phenomenon of QS is a cell-to-cell communication mechanism that uses molecules called autoinducers to regulate gene expression in response to environmental and cell density changes (23).

The first QS mechanism described involved a 17-amino-acid peptide (competence-stimulating peptide [CSP]) secreted by S. pneumoniae that regulates its competence state (50). Besides this QS system, S. pneumoniae reference strains (e.g., D39 and TIGR4) contain a luxS gene and produce AI-2 (21, 48). Some evidence suggests that this LuxS-controlled QS system might be part of the regulatory network controlling competence and LytA-dependent autolysis (43). In terms of pathogenicity, LuxS was implicated in virulence and persistence in the nasopharynx by using mouse models of pneumococcal infection (21, 48). The LuxS-generated signal has been implicated in differential expression of proteins in strain D39 (48) and regulation of genes involved in some metabolic processes, including the pneumolysin (Ply) gene (ply) (21). In this work, we demonstrate, for the first time, that LuxS plays a major role in controlling biofilm formation by S. pneumoniae strain D39. Two different D39-derivative luxS mutants were unable to produce early biofilms, while this phenotype was reversed by genetic complementation or physical complementation. Together, these results shed light on a new and important regulatory network of one of the most important human bacterial pathogens, S. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and bacterial culture media.

The S. pneumoniae reference and derivative strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All of the other invasive S. pneumoniae strains isolated from blood or cerebrospinal fluid (n = 53) and normal-flora strains (n = 50) belong to our laboratory collection. These strains were isolated in different geographic regions, including but not restricted to the United States, Spain, Taiwan, Peru, and Brazil. Identification and serotyping were performed by standard procedures (8). S. pneumoniae strains were cultured on blood agar plates (BAP) or Todd-Hewitt broth containing 0.5% (wt/vol) yeast extract (THY). When indicated, 2% (wt/vol) maltose, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (1 μg/ml), erythromycin (0.5 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (110 μg/ml) was added to the culture medium.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae strains | ||

| D39 | Avery strain, clinical isolate, capsular serotype 2 | 6, 26 |

| R6 | D39-derivative, unencapsulated laboratory strain | 26 |

| TIGR4 | Invasive clinical isolate, capsular serotype 4 | 49 |

| SPJV01 | D39/pMV158GFP Tetr | This study |

| EJ3 | D39-derivative luxS-null mutant, Specr | 21 |

| SPJV02 | EJ3/pPP2 Specr Tetr | This study |

| SPJV04 | EJ3/pJVPP9 Specr Tetr | This study |

| SPJV05 | D39-derivative luxS-null mutant, Eryr | This study |

| SPJV06 | SPJV05/pJVR6 Eryr Specr | This study |

| SPJV07 | SPJV05/pJVPP9 Eryr Tetr | This study |

| SPJV08 | SPJV05/pMV158GFP Eryr Tetr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| TOP10 | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| ECJV10 | TOP10/pJVR6 | This study |

| ECJV11 | TOP10/pJVPP9 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | Cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pReg696 | Low-copy-number plasmid for Gram-positive bacteria | 14 |

| pPP2 | Integrative plasmid for S. pneumoniae strains | 15 |

| pJVPP9 | pPP2 containing the WT luxS gene from strain D39 | This study |

| pJVR6 | pReg696 containing the WT luxS gene from strain D39 | This study |

| pLux-ery-Lux | pCR2.1-TOPO containing the luxS-ery-luxS cassette | This study |

| pMV158GFP | S. pneumoniae mobilizable plasmid containing the green fluorescent protein gene | 36 |

DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA from the S. pneumoniae strains in Table 1 was purified from overnight cultures on BAP using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA-containing supernatant from invasive isolates and normal-flora strains was extracted by the Chelex method (10).

PCRs.

Reactions were performed with genomic DNA (∼100 ng) or DNA-containing supernatant (3 μl) as the template, the indicated pair of primers at 1 μM (Fig. 1A and Table 2), 1× Taq master mix (New England BioLabs), and DNA grade water. PCRs were run in a MyCycler Thermal Cycler System (Bio-Rad). Products were run in 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed using a ChemiDoc XRS gel documentation System (Bio-Rad).

Fig. 1.

Overlapping-PCR approach used to locate the luxS gene in S. pneumoniae isolates. (A) Schematic representation of an ∼6.2-kb region that includes the QS luxS gene. Solid bars underneath the locus diagram depict the primers used for the overlapping PCRs shown in panel B. (B) DNAs from a collection of invasive S. pneumoniae isolates and normal-flora strains (lanes 1 to 15), ATCC 33400 (lane 16), and TIGR4 (lane 17) were used as templates in PCRs with the primers indicated at the right. The size, in base pairs, of the PCR product obtained is shown to the left of each panel.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Target gene(s)a | Sequenceb | PCR product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JVS1L | pbp2X-mraY | AGTAAGTCAACAAAGTCCTTATCC | 600 |

| JVS2R | TATTGCTGAATTGGCTACTAAATA | ||

| JVS3L | mraY-clpL | GGTAAATGAAAGCCTTACTAGAAC | 482 |

| JVS4R | TGTTAAGTTTCGACCTAGTTTTG | ||

| JVS5L | clpL-luxS | CTAAGGAAGACCTTTCTAAGATTG | 953 |

| JVS6L | ACATCATCTCCAATTATGATATTC | ||

| JVS7L | luxS-Sp0341 | CTATCACAGCTACAGAAAATCCT | 306 |

| JVS8R | AAAACTTTCGACAATAACTTCTTT | ||

| lytA-L | lytA | AGTTTAAGCATGATATTGAGAAC | 272 |

| lytA-R | TTCGTTGAAATAGTACCACTTAT | ||

| luxS-L | luxS | ACATCATCTCCAATTATGATATTC | 257 |

| luxS-R | GACATCTTCCCAAGTAGTAGTTTC | ||

| 0341-L | Sp0341 (560) | TATGTCCAATATGTACCACGAC | 386 |

| 0341-R | TGAAGTCAAGAACTGTTTGATAGT | ||

| gyrB-L | gyrB | AATAGTTGGAGATACGGATAAAAC | 227 |

| gyrB-R | TATATTCAACGTAACTAGCAATCC | ||

| 16SrRNA-L | rpsP | AACCAAGTAACTTTGAAAGAAGAC | 126 |

| 16SrRNA-R | AAATTTAGAATCGTGGAATTTTT | ||

| LuxP2-L | luxS | TTGGTACCGAGAGGTTTTCTCTCTGTCTCA | 554 |

| LuxP2-R | TTTCTAGATTAAATCACATGACGTTCAAAG | ||

| Ery-L | ermB | AAAAATTTGTAATTAAGAAGGAGT | 795 |

| Ery-R | CCAAATTTACAAAAGCGACTCA | ||

| Lux5-L | luxS (30) | TTGGTACCGAACTTGACCACACCATTGTC | 208 |

| Lux5-R | TTGGATCCATGGTGAACAGTCAATCATGC | ||

| Lux3-L | luxS (275) | TTCTCGAGACGTCACACCAGTGCTAAAAT | 159 |

| Lux3-R | TTTCTAGAATGAGTCTTGCCCATTCTTTA | ||

| LuxReg-L | luxS | TTGGATCCGAGAGGTTTTCTCTCTGTCTCA | 554 |

| LuxReg-R | TTGAGCTCTTAAATCACATGACGTTCAAAG | ||

| Cps4A-L | cps4A | CGTCTAAGAGTCAGTCTTTCAATA | 266 |

| Cps4A-R | ATTGATATCCACTCCATAGAGATT | ||

| nanA-L | nanA | CAGTGATAGAAAAAGAAGATGTTG | 212 |

| nanA-R | ATTATTGTAAACTGCCATAGTGAA | ||

| PspA-L | pspA | CATAGACTAGAACAAGAGCTCAAA | 214 |

| PspA-R | CTACATTATTGTTTTCTTCAGCAG | ||

| Ply-L | ply | TGAGACTAAGGTTACAGCTTACAG | 225 |

| Ply-R | CTAATTTTGACAGAGAGATTACGA |

When indicated (in parentheses), the position of the primer is relative to the hypothetical first ATG of the indicated gene of WT strain D39 (GenBank accession number CP000410).

Italics show restriction enzyme sites added for cloning purposes.

RNA extraction.

Total RNA was extracted as previously described (54, 55). Briefly, a cell suspension was prepared using 200 μl of acetate solution (20 mM sodium acetate [pH 5], 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [Bio-Rad]) with 200 μl of saturated phenol (Fisher Scientific) added. This was incubated at 60°C in a water bath with vigorous shaking for 5 min and centrifuged at 17,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Cold ethanol was added to the supernatant obtained and mixed well by inverting the tube, and the mixture was centrifuged at 17,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min to obtain the RNA pellet. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of DNase-free, RNase-free water and additionally treated with 2 U of DNase I (Promega) at 37°C for 30 min. The RNA concentration was quantified, and samples were stored in 20-μl aliquots at −80°C.

qRT-PCR analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR was performed using the iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad) and the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCRs were performed in triplicate with 20 ng of total RNA and a 500 nM concentration of each primer (Table 2) under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 50°C for 20 min, 1 cycle of 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 55°C for 1 min. Melting curves were generated by a cycle of 95°C for 1 min and 55°C for 1 min and 80 cycles of 55°C with 0.5°C increments. The relative quantitation of mRNA expression was normalized to the constitutive expression of the 16S rRNA housekeeping gene and calculated by the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method (27).

Preparation of D39-derivative luxS mutant SPJV05 and complemented strains.

To inactivate the luxS gene in strain D39, a DNA cassette containing the ermB gene (which confers resistance to erythromycin) flanked by the 5′ and 3′ regions of luxS was prepared. Briefly, ermB was PCR amplified using primers Ery-L and Ery-R (Table 2) and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. The 5′ (∼210 bp) and 3′ (∼160 bp) sequences of luxS were PCR amplified using primers Lux5-L and Lux5-R and primers Lux3-L and Lux3-R, respectively. The PCR fragments obtained were purified using QIAquick gel extraction (Qiagen) and digested with KpnI and BamHI (5′ luxS fragment) or XhoI and XbaI (3′ luxS fragment). The digested fragments were again purified and ligated, using T4 DNA ligase (Promega), upstream or downstream, respectively, of pCR2.1-TOPO containing ermB to create plasmid pLuxS-ery-LuxS. The whole luxS-ery-luxS cassette (∼1.1 kb) was PCR amplified and then purified.

The luxS-ery-luxS cassette was transformed into competent cells of wild-type (WT) strain D39 by standard procedures (18). This transformation reaction mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C, plated onto BAP containing erythromycin, and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Colonies were screened by PCR using primers Lux5-L and Lux3-R, and a transformant named SPJV05 was obtained. The luxS mutation was also verified by sequencing. Another D39ΔluxS mutant strain, EJ3, previously prepared and characterized (21), was kindly provided by Elizabeth Joyce of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Stanford University School of Medicine.

To prepare complemented strains, the luxS WT gene was amplified using primers LuxReg-L and LuxReg-R or LuxP2-L and LuxP2-R (Table 2) and cloned into Gram-positive plasmid pReg696 (14) or the S. pneumoniae integrative vector pPP2 (15) to create pJVR6 and pJVPP9 (Table 1). Plasmid pJVR6 or pJVPP9 was extracted from ECJV10 or ECJV11 and used to transform competent cells of SPJV05 to create SPJV06 or SPJV07, respectively (Table 1). EJ3, resistant to spectinomycin, was only complemented with pJVPP9 or pPP2 (the empty vector).

Preparation of the inoculum for biofilm assays.

An overnight BAP culture was used to prepare a cell suspension in THY broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere until the culture reached an OD600 of ∼0.2. An aliquot (7 × 105 CFU/ml) was inoculated in triplicate into either an 8-well glass slide (Lab-Tek) or a polystyrene-treated 96- or 24-well microtiter plate (Corning) containing THY with no antibiotics and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for the indicated times.

Quantification of biofilm biomass by crystal violet.

Biofilms were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then allowed to dry for 15 min. Crystal violet (0.4%) was then added, and the biofilms were incubated for 15 min. After washing, crystal violet-stained biofilms were further dried at room temperature for 15 min. To quantify biofilm biomass, crystal violet was removed by adding 33% acetic acid solution. The A630 of solubilized dye was obtained in a Epoch microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek).

Quantification of biofilm biomass by a fluorescence-based assay.

Biofilms were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 min and made permeable by the addition of 0.5% Triton X-100 (Roche) and incubation for 5 min at room temperature. After being washed three times with PBS, biofilms were blocked by adding 2% bovine serum albumin and stained for 1 h at room temperature with a polyclonal anti-S. pneumoniae antibody (∼40 μg/ml) coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; ViroStat, Portland, ME). To quantify biofilm biomass, FITC fluorescence readings (arbitrary units) were obtained using a VICTOR X3 Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin-Elmer). The number of arbitrary fluorescence units of 24-h biofilms of WT strain D39 was set to a biofilm biomass of 100% and used to calculate the biofilm biomass percentages of all of the other S. pneumoniae strains tested or at different time points.

Physical complementation of the biofilm phenotype and AI-2 studies.

To assess physical complementation, a mixture of two strains was incubated in the same biofilm assay but the biomass of only one strain was quantified. Briefly, WT strain D39 or strain SPJV05 was transformed with plasmid pMV158GFP, which contains the gfp gene under the control of the inducible maltose promoter (36), to create SPJV01 or SPJV08, respectively (Table 1). The biofilm biomass of each of these fluorescent versions was similar to that of its parent strain (data not shown). A mixture of WT strain D39 and SPJV08 or WT strain D39 and SPJV01 was then inoculated into the same biofilm bioassay. As a control, SPJV01 or SPJV08 was also inoculated into individual wells. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, biofilms were washed and fluorescence readings or images were immediately obtained. For these experiments, the number of arbitrary fluorescence units obtained from SPJV01 biofilms was set to 100% of the biofilm biomass and the biofilm biomasses of all of the other experimental conditions were calculated.

To physically separate the bacteria within the same biofilm assay, two chambers were created within the same well by installing a Transwell filter device (Corning, Corning, NY). The Transwell membrane (0.4 μm) creates a physical barrier that is impermeable to bacteria but allows the passage of small molecules between the two chambers (top and bottom). The WT D39 strain was inoculated into the top chamber (Transwell filter), while SPJV08 was inoculated into the bottom chamber. To further confirm whether LuxS mediates this secreted QS signal, luxS mutant strain SPJV05 was inoculated into the top chamber and SPJV08 was inoculated into the bottom chamber. These Transwell biofilm bioassays were incubated for 6 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and the biofilms produced by SPJV08 in the bottom chamber were quantified and photographed as described above.

For AI-2 studies, D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated in triplicate into 96-well plates with or without different concentrations (0.1 to 100 nM) of chemically synthesized AI-2 (dihydroxypentanedione; Omm Scientific) as used elsewhere (4, 9, 42) and incubated for 24 h. Biofilms were stained with fluorescent antibody, and biomass was calculated as described earlier. A concentration of 10 nM induced a statistically significantly different biofilm biomass when incubated along with D39 or SPJV05.

Statistical analyses.

All data were analyzed using the nonparametric two-tailed Student t test and the Minitab 15 software.

RESULTS

The luxS gene is located in the same chromosomal region in S. pneumoniae isolates.

Bioinformatic analysis of S. pneumoniae strains whose genomes have been sequenced indicated that the luxS gene is located in a region that contains genes involved in division and cell wall biosynthesis. Specifically, luxS is situated upstream (∼6.4 kb) of the gene cps4A (encoding a capsule polysaccharide biosynthesis protein) and ∼4 kb downstream of the pbp2X gene, whose encoded protein is involved in cell wall biosynthesis and is a target of β-lactam antibiotics (30, 57), followed by mraY (encoding a phospho-N-acetylmuramoyl-pentapeptide-transferase [∼3 kb]) (29) and, ∼294 bp downstream, the clpL gene, which encodes a putative ATP-dependent Clp protease (Fig. 1A).

To investigate the presence of the luxS gene among S. pneumoniae strains, PCR analyses were performed with DNA extracted from invasive isolates and strains isolated from the nasopharynges of healthy children. Those PCR analyses revealed that all of the isolates surveyed (n = 103) contained the luxS gene (Fig. 1B). To further study the location of the luxS gene, primers were designed so that a series of overlapping PCRs mapped its chromosomal location. This overlapping-PCR approach demonstrated that the luxS gene is always located downstream of an open reading frame (ORF) annotated as Sp0341 (TIGR4 annotation), which encodes a protein of unknown function. The size of the PCR product obtained was always the same and so included, as predicted by bioinformatic analysis, an intergenic region of ∼94 bp between Sp0341 and the luxS gene (Fig. 1A and B).

Downstream of luxS in all of the isolates surveyed, overlapping PCR identified a gene annotated as clpL, encoding a putative ATP-dependent protease (Fig. 1B). For some invasive isolates (n = 23) or normal-flora strains (n = 19), the size of the PCR product correlated with that observed when using as the template the DNA of reference strain ATCC 33400, which belongs to serotype 1 (∼1,200 bp). All of the other strains allowed the amplification of a product (∼960 bp) similar to that of TIGR4 (serotype 4). The size of those PCR products could not be correlated with serotypes of the strains surveyed (not shown). Overlapping PCR detected the genes mraY and pbp2X downstream of luxS in 17 normal-flora strains and 22 invasive isolates (Fig. 1B). PCR analysis targeting mraY or pbp2X further clarified that these genes were not located in this position by the rest of the strains (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the luxS gene is located near the capsule locus (cps) in all of the S. pneumoniae isolates surveyed.

Transcription of the luxS gene.

In S. bovis and S. pyogenes, a homologous luxS gene is transcribed during the early mid-log phase of growth as a monocistronic message (5, 46). Unlike S. bovis, whose direction of transcription is the opposite of that of both its upstream and downstream genes (5), in S. pneumoniae, the direction of transcription of luxS is the same as that of its upstream gene (Sp0341) and the opposite of that of the downstream clpL gene (Fig. 1A).

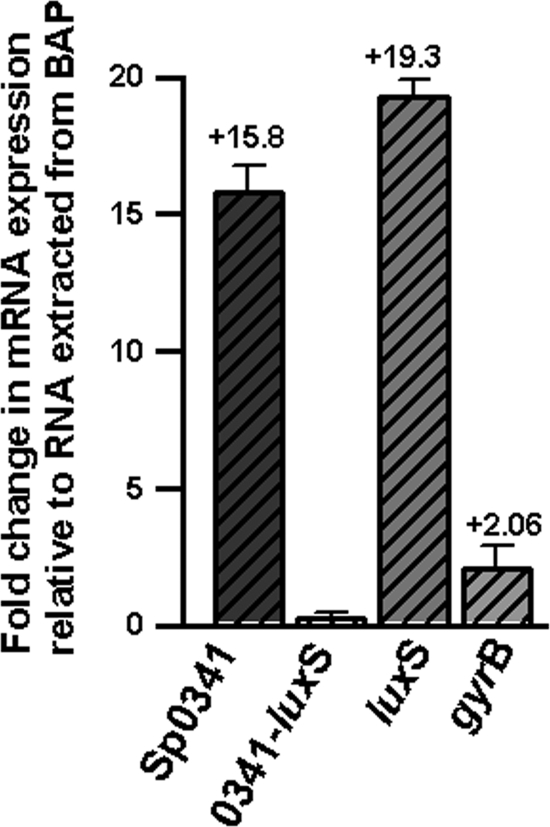

To evaluate whether luxS mRNA is cotranscribed with Sp0341 by S. pneumoniae strain D39, qRT-PCR analyses were performed. These analyses showed that at 4 h postinoculation, levels of luxS transcripts increased ∼20-fold with respect to the RNA from BAP (Fig. 2). While expression of Sp0341 mRNA also increased ∼16-fold, almost no change (∼0.5) was obtained for that of Sp0341-luxS. As expected, the transcription of a housekeeping gene used as an internal control (gyrB) did not change appreciably. Similar results were obtained by RT-PCR with S. pneumoniae strains TIGR4 and ATCC 33400 (not shown). Overall, these results indicate that the luxS gene of S. pneumoniae is transcribed as a monocistronic message during the mid-log phase of growth.

Fig. 2.

Monocistronic transcription of the luxS gene during the mid-log phase of growth. qRT-PCRs were performed with RNA extracted from D39 grown overnight in BAP or THY broth at 4 h postinoculation. Primers amplified ORF Sp0341, Sp0341 and the luxS gene (0341-luxS), the luxS gene, or the gyrase B subunit gene. Average CT values were normalized to the 16S rRNA housekeeping gene, and n-fold differences were calculated by the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method (27). The values above the bars indicate the calculated n-fold changes relative to the overnight BAP culture. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean calculated using data from three independent experiments.

Development of a new fluorescence-based assay to quantify S. pneumoniae biofilm biomass.

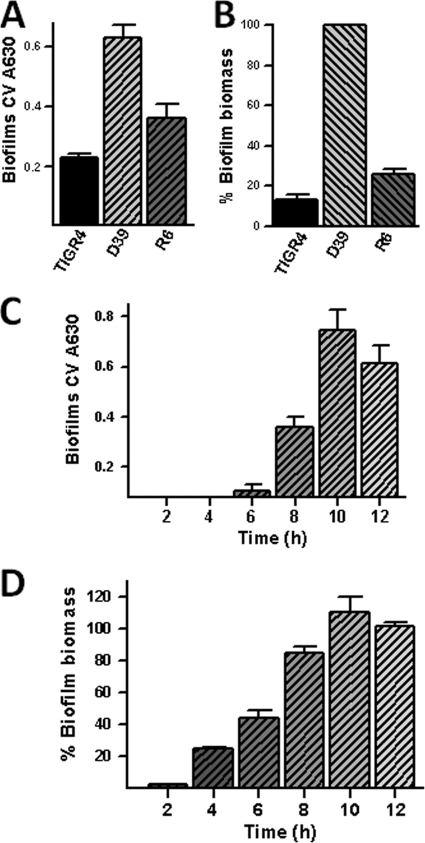

Before addressing the role of LuxS in S. pneumoniae biofilms, we quantified the biofilm biomass produced by reference strains D39 and TIGR4 and strain R6, a nonencapsulated variant of strain D39. As shown in Fig. 3A, the crystal violet assay demonstrated biofilm formation by all of the strains. The TIGR4 biofilm biomass was low (A630, <0.3), as previously described by Muñoz-Elías et al. (34). S. pneumoniae strain D39 produced more robust biofilms than either TIGR4 or R6 in 96-well plates (Fig. 3A) or 24-well plates (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Quantification of the biofilm biomass of S. pneumoniae strains. (A and B) An aliquot of the indicated strain was inoculated in triplicate into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. In panels C and D, S. pneumoniae D39 was inoculated and incubated for the indicated time. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet (A and C) or with an anti-S. pneumoniae polyclonal antibody coupled to FITC (B and D). The biofilm biomass (arbitrary fluorescence units) of WT strain D39 at 24 h postinoculation was adjusted to 100%, and the biomass percentages of the other strains or time points were calculated.

To optimize and improve the biofilm assay for S. pneumoniae strains, we developed a new fluorescence-based assay using an anti-S. pneumoniae antibody which is coupled to fluorescein. This fluorescent antibody will bind to the pneumococcus cell wall and stain the biofilm structure. Once formed, 24-h biofilms were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and stained. We found that permeabilizing the biofilms with Triton X-100 produces a stable and reproducible quantification of fluorescence (data not shown). Arbitrary fluorescence units confirmed the tendency of strain D39 to form more biofilm biomass at 24 h postinoculation than strain TIGR4 or R6 (Fig. 3B). This new biofilm assay was more sensitive than the crystal violet assay. While biofilms stained with crystal violet began to be detectable at 6 h postinoculation (Fig. 3C), at the same time point, ∼50% of the biofilm biomass was already detected by the fluorescence assay (Fig. 3D).

The LuxS-controlled QS mechanism regulates S. pneumoniae biofilms.

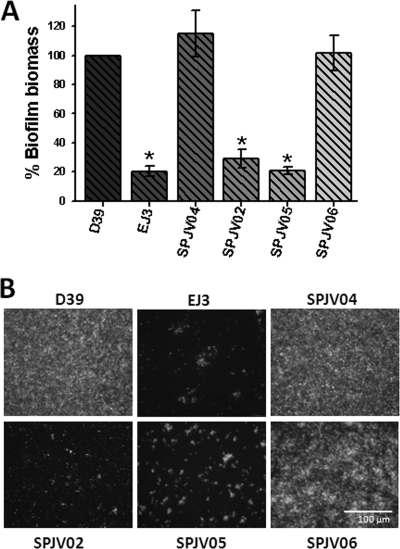

To study the role of LuxS in pneumococcus biofilms, WT strain D39 and isogenic derivative luxS mutants SPJV05 and EJ3 were assessed using our newly developed fluorescence-based biofilm assay. In comparison with D39, SPJV05 or EJ3 produced only ∼20% of the biofilm biomass at 24 h postinoculation (Fig. 4 A). Epifluorescence images of biofilms produced by WT strain D39 showed bacteria attached to the bottom, covering the entire surface of the well (Fig. 4B). A higher magnification (×63) showed that the structure formed by D39 is highly organized, forming compact layers of bacteria that create aggregates where the fluorescence signal is more intense (not shown). In contrast, fluorescence images of biofilms produced by SPJV05 or EJ3 clearly show few bacteria attached to the bottom of each well (Fig. 4B). Indeed, both mutants appear to form small aggregates in the bottom of the well that do not progress to form a mature biofilm (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Biofilm formation by S. pneumoniae strain D39 is regulated by the luxS gene. (A) The indicated strain was inoculated into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. Biofilms were stained by a fluorescent antibody, and the biomass of WT strain D39 was adjusted to 100% to calculate all of the others. In all of the panels, the error bars represent the standard error of the mean calculated using data from at least four independent experiments. Asterisks indicate values statistically significant differences from that of WT strain D39 (P ≤ 0.05, calculated using a nonparametric t test). (B) Biofilms were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope. The bar in the bottom right panel is valid for all of the panels.

To confirm the role of luxS in S. pneumoniae biofilms, complemented strains SPJV04 and SPJV06 were assessed for biofilm production. As shown in Fig. 4A, complementation of luxS mutants with a copy of luxS integrated either in bgaA or in a plasmid, SPJV04 and SPJV06, respectively, restored the biofilm biomass to the WT level. Production of biofilm biomass by SPJV02, containing the pPP2 empty vector, was similar to that of EJ3 (Fig. 4A), demonstrating that disruption of bgaA did not alter the biofilm phenotype. Epifluorescence images of SPJV04 and SPJV06 biofilms show structures similar to that of WT strain D39 (Fig. 4B).

This biofilm phenotype is likely not due to growth rates or an autoaggregation defect. Comparative growth studies showed that D39 and its derivatives grew similarly in THY (not shown) Time course studies also demonstrated that luxS mutants and complemented strains autoaggregate similarly to strain D39 (data not shown).

LuxS regulates early events in biofilm formation.

To begin exploring the mechanism by which LuxS controls biofilm formation, a time course study was conducted that evaluated the early production of biofilms. Figure 5A shows that at 3 h postinoculation, ∼10% of the biofilm biomass had already been produced by the WT strain. The biofilm biomass reached ∼25%, ∼45%, and ∼80% after 4, 6, and 8 h of incubation, respectively (Fig. 5A), while the biofilm biomass at 10 or 12 h postinoculation was similar to that produced in a 24-h period (not shown). In contrast, biofilms produced by SPJV05 were undetectable at early time points (i.e., 2 or 4 h postinoculation) while at 8 h postinoculation, only ∼15% of the 24-h biofilm biomass was found (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Time course study of biofilm formation. Strain D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated into 96-well plates and incubated for 1 to 8 or 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. (A) Biofilms were stained with an anti-S. pneumoniae antibody coupled to FITC and quantified using a fluorometer. The biofilm biomass of WT strain D39 at 24 h postinoculation was set to 100%, and all of the others were calculated. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean calculated by using data from three independent experiments. The asterisk indicates a value statistically significantly different from that of WT strain D39 at 8 h postinoculation (P ≤ 0.05, calculated using a nonparametric t test). Biofilms formed by WT strain D39 at 2 h (B), 4 h (C), 6 h (D), or 8 h (E) postinoculation, by strain SPJV05 at 8 h postinoculation (F), and by complemented strain SPJV06 at 8 h postinoculation (G) were imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope. The bar in the bottom left panel is valid for all of the panels.

As shown in Fig. 5B, small pneumococcus aggregates could be detected as early as 2 h postinoculation with the WT strain. Those D39 aggregates became more evident after 4 and 6 h of incubation and covered almost the entire surface after 8 h (Fig. 5C, D, and E). Bacterial aggregates produced by SPJV05, however, were smaller and covered only ∼20% of the surface at 8 h postinoculation (Fig. 5F). As expected, the complemented strain produced a biofilm biomass similar to that of the WT at 8 h postinoculation (Fig. 5G).

Evidence that LuxS-mediated AI-2 regulates early biofilm formation.

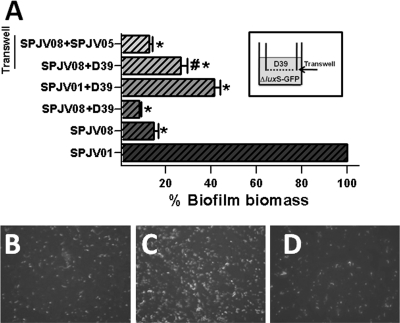

To confirm that a QS signal was responsible for the biofilm defect of the luxS mutants, the WT strain and SPJV08 (SPJV05 containing the gfp gene under the control of the maltose promoter) were inoculated into the same well with or without physical contact. If a QS signal released by the WT could induce an increase in SPJV08 biofilm biomass, SPJV08 fluorescence would increase.

When WT strain D39 and strain SPJV08 were inoculated together with physical contact, the biofilm biomass of strain SPJV08 was similar to the level of strain SPJV08 alone and statistically significantly different from the levels produced by WT strain D39 containing pMV158GFP (SPJV01) (Fig. 6 A). Even when SPJV08 was cocultured with D39, there were almost no bacterial aggregates of fluorescent SPJV08 at 6 h postinoculation (Fig. 6B). We hypothesize that the WT strain was able to attach to the surface and produced early biofilms but was unable to incorporate cells of the luxS-null mutant once initial aggregates had formed. As a control, the WT strain and SPJV01 were inoculated together and incubated for 6 h. The biofilm biomass of SPJV01 was ∼40%, demonstrating that the WT strain outcompeted SPJV01 to produce biofilms (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Physical complementation of the biofilm phenotype of the luxS mutant. (A) SPJV01, SPJV08, or a mixture of the indicated strains was inoculated into 24-well microplates and incubated for 6 h. Transwell filters were installed in some of the wells (inset), and SPJV08 was inoculated into the bottom and D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated into the top. These Transwell biofilm bioassays were also incubated for 6 h, and the biofilms produced by SPJV08 on the bottom was quantified. The symbol * or # indicates a value statistically significantly different (P ≤ 0.05, calculated using a nonparametric t test) from that of WT strain D39 or SPJV05, respectively. GFP, green fluorescent protein. Panel B shows the fluorescence image of SPJV08 inoculated along with WT strain D39 and incubated for 6 h. Also shown are fluorescent biofilms formed by SPJV08 on the bottom of a Transwell biofilm bioassay when WT strain D39 (C) or SPJV05 (D) was been inoculated into the top chamber and incubated for 6 h.

To avoid the formation of biofilms by WT strain D39 when it was coinoculated with SPJV08 but allow the secretion of a secreted factor, a Transwell device was used. This system contains a membrane (0.45 μm) that allowed the inoculation of the WT strain into the top and SPJV08 into the bottom while they were physically separated (Fig. 6A, inset). Given its pore size, the membrane allows the passage of small molecules. As shown in Fig. 6A, when the WT strain and SPJV08 where coinoculated, SPJV08 was able to produce ∼25% of the WT biofilm biomass at 6 h postinoculation (Fig. 6A and C). This biofilm level was statistically significantly different from the level produced by SPJV08 alone (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the biofilm biomass of SPJV08 that had been inoculated into the bottom of the well and SPJV05 in the Transwell system was not significantly different from that of SPJV08 alone (Fig. 6A).

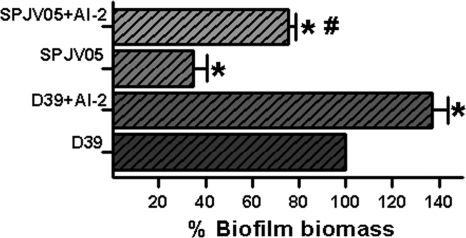

To confirm the role of secreted AI-2 in the biofilm phenotype, strain D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated along with chemically synthesized AI-2. As shown in Fig. 7, AI-2 allowed the production of a biofilm biomass greater than that produced by strains grown with no purified AI-2.

Fig. 7.

Exogenous AI-2 increases the biofilm biomass of the WT and the luxS mutant. Strain D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated into 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Where indicated, AI-2 (10 μM) was added to the wells. Biofilms were stained with a fluorescent antibody, the biomass of WT strain D39 was set to 100%, and all of the others were calculated. The symbol * or # indicates a value statistically significantly different (P ≤ 0.05, calculated using nonparametric t test) from that of WT strain D39 or SJPV05, respectively.

Temporal expression of the luxS gene and evidence that LuxS regulates lytA mRNA and ply mRNA levels.

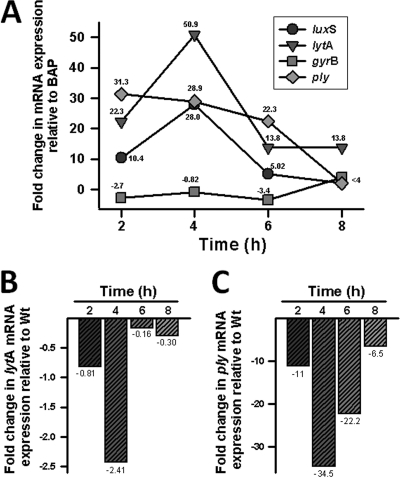

Since we had demonstrated that LuxS regulates early biofilm formation, a time course study was conducted to evaluate levels of luxS mRNA expression during the early mid-log phase of growth. The luxS transcript was found to be maximally expressed (∼28-fold increase) at 4 h postinoculation (Fig. 8 A). At that time point, the changes in luxS mRNA in some invasive isolates and normal flora ranged from ∼6 to ∼300-fold and expression could not be correlated to the subset of strains (data not shown). A clear decline in the levels of luxS mRNA in strain D39 was obtained at 6 h (5-fold difference) and 8 h (3.8-fold difference) postinoculation. As expected, gyrB mRNA levels did not significantly change after 2, 4, 6, or 8 h of incubation (Fig. 8A). These results indicate that the transcription of the luxS gene, and therefore its activity, is maximal during the early mid-log phase of growth.

Fig. 8.

Regulation of lytA mRNA and ply mRNA transcripts by luxS. Strain D39 or SPJV05 was inoculated into THY broth and incubated for 2, 4, 6, or 8 h at 37°C. RNA was extracted from these THY cultures or from an overnight culture in BAP. (A) RNA from WT strain D39 was used as the template in qRT-PCRs with primers that amplified the lytA, luxS, ply, or gyrB gene. Average CT values were normalized to the 16S rRNA gene, and the n-fold differences, relative to BAP, were calculated using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCT) method (27). The value at each time point is the calculated n-fold difference from that of the overnight BAP culture. (B and C) RNA from D39 or SPJV05 was used as the template in qRT-PCRs with primers targeting the lytA gene (B) or the ply gene (C). Average CT values were normalized to the 16S rRNA gene, and the n-fold differences from that of WT strain D39 were calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are representative values for three independent biological replicates.

Previous studies have demonstrated that LytA, the capsular polysaccharide, the neuraminidase NanA, and choline binding proteins such as PspA play a role in S. pneumoniae biofilm formation (32, 40). Increased levels of Ply have also been detected in S. pneumoniae early biofilms (2). Therefore, the transcription of genes and potential LuxS-mediated regulation were evaluated. Our qRT-PCR analyses demonstrated that WT lytA, ply, cps4A, nana, and pspA mRNA levels similarly increased during the early mid-log phase of growth and then decreased by 6 h postinoculation (Fig. 8A and data not shown). In contrast, lytA mRNA levels in the luxS mutant decreased by 4 h postinoculation (Fig. 8B), while levels of the ply transcript dramatically decreased by 2, 4, and 6 h postinoculation (Fig. 8C). The transcription levels of the nanA, csp4A, and pspA genes remained similar to those of the WT (data not shown). Complemented stains showed transcript levels similar to that of the WT at all time points (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

S. pneumoniae strains usually colonize the nasopharynges of healthy children during the first months of life and either leave the children asymptomatic or go on to cause diseases such as pneumonia, meningitis, and otitis media (17, 37). It has been postulated that the pneumococcus resides in the human nasopharynx, forming biofilms (33). Despite the increasing importance of S. pneumoniae biofilms during the last few years, the regulatory network behind these structures has not been completely elucidated. The present study demonstrates, for the first time, that the luxS-controlled QS system regulates S. pneumoniae early biofilm formation. This AI-2-mediated regulatory network appears to be specific for a subset of biofilm effectors, since in this research and elsewhere (21), LuxS was found to regulate a particular set of genes in planktonic cultures.

Recent experimental evidence indicates that the LuxS QS system is implicated in the persistence, virulence, and dissemination of S. pneumoniae (3, 21, 48). A previous study by Stroeher et al. (48) demonstrated that a D39-derivative luxS-null mutant was less able to spread to the lungs or the blood than was WT strain D39, suggesting that the QS signal might be important for dissemination within the host. This luxS mutant was also less virulent for mice than WT strain D39 was (48). Another study, by Joyce et al. (21), showed that this QS system is implicated in persistence in the mouse nasopharynx. Our results extend these observations by demonstrating that LuxS is absolutely required for the establishment of early biofilm structures. While luxS mutants were unable to form early biofilms, the phenotype was fully restored in the complemented strains. In an attempt to verify that a secreted QS signal was controlling early biofilms, we used chemically synthesized AI-2 or AI-2 containing supernatants from WT strain D39 that demonstrated statistically significantly more biofilm biomass when AI-2 was incubated along with the luxS mutant or the WT (Fig. 7).

Recent publications have also shown that the competence QS system (Com), which is regulated by the secreted CSP, controls biofilm production by S. pneumoniae strains (38, 52). An investigation by Oggioni et al. (38) showed that supplementing strain D39 with exogenous CSP produces more biofilm biomass, and in a more recent publication, Trapetti et al. (52) demonstrated that a TIGR4-derivative comC mutant was unable to form biofilms, while the phenotype could be restored by adding exogenous CSP. Specific CSP-regulated biofilm effectors and potential LuxS-Com synergism for biofilm development, if any exist, remain to be investigated.

The present study shows that the luxS gene is located near the capsular locus in S. pneumoniae strains and transcribed as a monocistronic unit. Expression of the capsular polysaccharide has been implicated in virulence (35) and biofilm formation (32); however, the LuxS system does not seem to regulate capsule genes, since our qRT-PCR studies showed that the luxS mutant contained a level of csp4A mRNA similar to that of the WT. Other proteins previously implicated in biofilms, such as the neuraminidase NanA (40) and choline binding protein PspA (32), were also found not to be regulated by this system. The expression of lytA, encoding the autolysin involved in cell wall degradation (20) and production of biofilms (32), however, was found to be regulated by LuxS during the mid-log phase of growth (Fig. 8B). Whereas our experiments showed that lytA transcripts were higher in the WT during the early mid-log phase (2 to 4 h) of growth, the mutant had reduced lytA mRNA levels at 4 h postinoculation. In line with these results, evidence indicating that LuxS may play a role in LytA-dependent autolysis in the stationary phase of growth (at 5 to 7 h postinoculation) has been published (43). Therefore, LuxS appears to regulate levels of lytA mRNA in exponentially growing cultures that results in a defect in the autolysis phenotype during the stationary phase. A complete characterization of the biology of this phenomenon is under way in our labs.

Evidence now directly links the production of pneumococcal biofilms with LuxS regulation. For instance, a previous report found that a luxS mutant had a protein expression profile (cytosolic and membrane proteins) different from that of WT strain D39 (48). Joyce et al. (21), using microarrays, detected 46 genes down- or upregulated by the LuxS system only when they used RNA extracted from WT strain D39 and the luxS mutant growing in the early mid-log phase of growth. Since levels of the luxS transcript are also higher during the early mid-log phase of growth (Fig. 8A) and the luxS mutant is unable to produce biofilms (Fig. 4A), regulation of genes encoding proteins implicated in early biofilm formation, such as lytA, should be a main target of the LuxS-generated signal.

The regulation of proteins present in early biofilms has been previously investigated (2). A particular association between early biofilm-produced proteins and the LuxS system was the discovery that levels of Ply, a protein implicated in colonization and virulence in animal models (19, 39), increase during early stages of biofilm formation (2). The gene that encodes it (ply) has also been shown by microarray analyses to be regulated by the LuxS system (21). Our studies extend this observation by demonstrating, by qRT-PCR, that LuxS dramatically impacts levels of ply transcripts during the early mid-log phase of growth (Fig. 8C). The contribution of Ply to S. pneumoniae-produced biofilms is unclear and, given that D39Δply has a reduced ability to colonize the mouse nasopharynx (39), requires further elucidation. It may have a role in initial attachment, since Ply is not secreted by pneumococcus but rather located in the cell wall (41).

Our study also introduced a new fluorescence-based biofilm assay that is specific for S. pneumoniae strains. While other nonspecific fluorescence methods have been used to visualize S. pneumoniae biofilms in vitro (2, 12, 32), our newly developed assay uses an anti-S. pneumoniae antibody coupled to FITC that permits the quantification of biofilm biomass and direct visualization of those structures in a single assay. This assay may also be useful for studies where a heterogeneous population of bacteria (i.e., normal-flora strains) are present with or within S. pneumoniae biofilms, for example, in samples collected from children with pneumococcal diseases, animal studies, and in vitro studies dissecting the contribution of other bacteria to pneumococcal biofilms.

An important feature of our assay is that the permeabilization of the biofilm structure with Triton X-100 may allow those anti-S. pneumoniae antibodies to reach most of the pneumococci within the biofilm matrix. Levels of arbitrary fluorescence units were consistently higher only when biofilms were made permeable before staining with the fluorescent antibody. Since S. pneumoniae biofilm structures have been calculated to be ∼25 μm thick (32), it is possible that the crystal violet dye does not reach all of the pneumococcus cells within the matrix. The new fluorescence assay is more sensitive, being able to both quantify and visualize early biofilm structures (bacterial aggregates) within 2 h postinoculation (Fig. 3). In contrast, our experiments and those reported by Muñoz-Elías et al. (34), who used crystal violet, detected S. pneumoniae biofilms at 6 to 8 h postinoculation.

Using this new assay to gain insights into biofilm biology has shown that pneumococcal biofilm formation involves three stages, (i) initial attachment between 2 and 4 h, (ii) formation of bacterial aggregates occupying ∼50% of the surface between 4 and 6 h, and (iii) biofilm development. Similar stages have been previously discerned using a continuous-flow biofilm reactor, although in that study the stages were observed between 1 and 6 days (2). Once bacterial aggregates were produced (stage 2), biofilms continued growing exponentially, even in the absence of planktonic cells (R. M. Kunkel et al., unpublished data). In fact, with the sole exception of cps4A, whose mRNA levels remained similar, biofilm cells showed levels of nanA, ply, pspA, and lytA transcripts at 6 h postinoculation that were higher than those of their counterpart planktonic cultures (data not shown), clearly demonstrating active metabolism within biofilm cells. Attempts to determine the levels of these transcripts in a luxS background failed because of the absence of biofilm cells at that time point.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the S. pneumoniae LuxS-controlled QS system regulates early biofilm formation. Biofilm structures might be important for S. pneumoniae strains to persist and possibly cause important diseases such as otitis media or pneumonia. Findings in the present study may have implications for developing new targets to reduce pneumococcal carriage and therefore pneumococcal disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by Public Health Service grant UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program, NIH, National Center for Research Resources (J.E.V.).

We thank Elizabeth Joyce at Stanford University for providing strain EJ3; Reinhold Brückner at the Department of Microbiology, University of Kaiserslautern, for providing pPP2; Finbarr Hayes at the University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, for providing pReg6969; and Lesley McGee at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Carlos Grijalva at Vanderbilt University for providing some S. pneumoniae isolates. Also, thanks to Manuel Espinoza at the Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas, Madrid, Spain, for his kind gift of plasmid pMV158GFP and to Joshua Shak for critical reading of and suggestions on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahmed N. A., Petersen F. C., Scheie A. A. 2009. AI-2/LuxS is involved in increased biofilm formation by Streptococcus intermedius in the presence of antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4258–4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allegrucci M., et al. 2006. Phenotypic characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 188:2325–2335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Armbruster C. E., et al. 2009. LuxS promotes biofilm maturation and persistence of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in vivo via modulation of lipooligosaccharides on the bacterial surface. Infect. Immun. 77:4081–4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armbruster C. E., et al. 6 July 2010, posting date Indirect pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in polymicrobial otitis media occurs via interspecies quorum signaling. mBio 1(3)pii:e00102–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asanuma N., Yoshii T., Hino T. 2004. Molecular characterization and transcription of the luxS gene that encodes LuxS autoinducer 2 synthase in Streptococcus bovis. Curr. Microbiol. 49:366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Avery O. T., Macleod C. M., McCarty M. 1944. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from Pneumococcus type III. J. Exp. Med. 79:137–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blehert D. S., Palmer R. J., Jr, Xavier J. B., Almeida J. S., Kolenbrander P. E. 2003. Autoinducer 2 production by Streptococcus gordonii DL1 and the biofilm phenotype of a luxS mutant are influenced by nutritional conditions. J. Bacteriol. 185:4851–4860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. da Gloria Carvalho M., et al. 2010. Revisiting pneumococcal carriage by use of broth enrichment and PCR techniques for enhanced detection of carriage and serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1611–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Keersmaecker S. C., et al. 2005. Chemical synthesis of (S)-4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione, a bacterial signal molecule precursor, and validation of its activity in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 280:19563–19568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Lamballerie X., Zandotti C., Vignoli C., Bollet C., de Micco P. 1992. A one-step microbial DNA extraction method using “Chelex 100” suitable for gene amplification. Res. Microbiol. 143:785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. del Prado G., et al. 2010. Biofilm formation by Streptococcus pneumoniae strains and effects of human serum albumin, ibuprofen, N-acetyl-l-cysteine, amoxicillin, erythromycin, and levofloxacin. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 67:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donlan R. M., et al. 2004. Model system for growing and quantifying Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms in situ and in real time. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4980–4988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. García-Castillo M., et al. 2007. Differences in biofilm development and antibiotic susceptibility among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from cystic fibrosis samples and blood cultures. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:301–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grady R., Hayes F. 2003. Axe-Txe, a broad-spectrum proteic toxin-antitoxin system specified by a multidrug-resistant, clinical isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1419–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Halfmann A., Hakenbeck R., Bruckner R. 2007. A new integrative reporter plasmid for Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 268:217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hall-Stoodley L., et al. 2006. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA 296:202–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hava D. L., LeMieux J., Camilli A. 2003. From nose to lung: the regulation behind Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1103–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Håvarstein L. S., Coomaraswamy G., Morrison D. A. 1995. An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:11140–11144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirst R. A., et al. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae deficient in pneumolysin or autolysin has reduced virulence in meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 197:744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jedrzejas M. J. 2001. Pneumococcal virulence factors: structure and function. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:187–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joyce E. A., et al. 2004. LuxS is required for persistent pneumococcal carriage and expression of virulence and biosynthesis genes. Infect. Immun. 72:2964–2975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kadioglu A., Weiser J. N., Paton J. C., Andrew P. W. 2008. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:288–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaper J. B., Sperandio V. 2005. Bacterial cell-to-cell signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 73:3197–3209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karatan E., Watnick P. 2009. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:310–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klugman K. P., Madhi S. A., Albrich W. C. 2008. Novel approaches to the identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae as the cause of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47(Suppl. 3):S202–S206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lanie J. A., et al. 2007. Genome sequence of Avery's virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 189:38–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lizcano A., Chin T., Sauer K., Tuomanen E. I., Orihuela C. J. 2010. Early biofilm formation on microtiter plates is not correlated with the invasive disease potential of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 48:124–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Massidda O., Anderluzzi D., Friedli L., Feger G. 1998. Unconventional organization of the division and cell wall gene cluster of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 144(Pt. 11):3069–3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maurer P., et al. 2008. Penicillin-binding protein 2x of Streptococcus pneumoniae: three new mutational pathways for remodelling an essential enzyme into a resistance determinant. J. Mol. Biol. 376:1403–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Merritt J., Qi F., Goodman S. D., Anderson M. H., Shi W. 2003. Mutation of luxS affects biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 71:1972–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moscoso M., Garcia E., Lopez R. 2006. Biofilm formation by Streptococcus pneumoniae: role of choline, extracellular DNA, and capsular polysaccharide in microbial accretion. J. Bacteriol. 188:7785–7795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moscoso M., Garcia E., Lopez R. 2009. Pneumococcal biofilms. Int. Microbiol. 12:77–85 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muñoz-Elías E. J., Marcano J., Camilli A. 2008. Isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm mutants and their characterization during nasopharyngeal colonization. Infect. Immun. 76:5049–5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nelson A. L., et al. 2007. Capsule enhances pneumococcal colonization by limiting mucus-mediated clearance. Infect. Immun. 75:83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nieto C., Espinosa M. 2003. Construction of the mobilizable plasmid pMV158GFP, a derivative of pMV158 that carries the gene encoding the green fluorescent protein. Plasmid 49:281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nobbs A. H., Lamont R. J., Jenkinson H. F. 2009. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:407–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oggioni M. R., et al. 2006. Switch from planktonic to sessile life: a major event in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 61:1196–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ogunniyi A. D., et al. 2007. Contributions of pneumolysin, pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA), and PspC to pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 75:1843–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parker D., et al. 2009. The NanA neuraminidase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is involved in biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 77:3722–3730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price K. E., Camilli A. 2009. Pneumolysin localizes to the cell wall of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:2163–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rickard A. H., et al. 2006. Autoinducer 2: a concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol. Microbiol. 60:1446–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Romao S., Memmi G., Oggioni M. R., Trombe M. C. 2006. LuxS impacts on LytA-dependent autolysis and on competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 152:333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sanchez C. J., et al. 12 August 2010, posting date The pneumococcal serine-rich repeat protein is an intra-species bacterial adhesin that promotes bacterial aggregation in vivo and in biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 6(8)pii:e1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sekhar S., Kumar R., Chakraborti A. 2009. Role of biofilm formation in the persistent colonization of Haemophilus influenzae in children from northern India. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:1428–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Siller M., et al. 2008. Functional analysis of the group A streptococcal luxS/AI-2 system in metabolism, adaptation to stress and interaction with host cells. BMC Microbiol. 8:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sloan G. P., Love C. F., Sukumar N., Mishra M., Deora R. 2007. The Bordetella Bps polysaccharide is critical for biofilm development in the mouse respiratory tract. J. Bacteriol. 189:8270–8276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stroeher U. H., Paton A. W., Ogunniyi A. D., Paton J. C. 2003. Mutation of luxS of Streptococcus pneumoniae affects virulence in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 71:3206–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tettelin H., et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tomasz A. 1965. Control of the competent state in Pneumococcus by a hormone-like cell product: an example for a new type of regulatory mechanism in bacteria. Nature 208:155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tomasz A. 2000. Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. Mary Ann. Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, NY [Google Scholar]

- 52. Trappetti C., et al. 2011. The impact of the competence quorum sensing system on Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms varies depending on the experimental model. BMC Microbiol. 11:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van der Poll T., Opal S. M. 2009. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet 374:1543–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vidal J. E., Chen J., Li J., McClane B. A. 2009. Use of an EZ-Tn5-based random mutagenesis system to identify a novel toxin regulatory locus in Clostridium perfringens strain 13. PLoS One 4:e6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vidal J. E., Ohtani K., Shimizu T., McClane B. A. 2009. Contact with enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells induces rapid upregulation of toxin production by Clostridium perfringens type C isolates. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1306–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weimer K. E., et al. 2010. Coinfection with Haemophilus influenzae promotes pneumococcal biofilm formation during experimental otitis media and impedes the progression of pneumococcal disease. J. Infect. Dis. 202:1068–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zerfass I., Hakenbeck R., Denapaite D. 2009. An important site in PBP2x of penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: mutational analysis of Thr338. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1107–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]