Abstract

Little is known regarding the function of γδ T cells, although they accumulate at sites of inflammation in infections and autoimmune disorders. We previously observed that γδ T cells in vitro are activated by Borrelia burgdorferi in a TLR2-dependent manner. We now observe that the activated γδ T cells can in turn stimulate dendritic cells in vitro to produce cytokines and chemokines that are important for the adaptive immune response. This suggested that in vivo γδ T cells may assist in activating the adaptive immune response. We examined this possibility in vivo and observed that γδ T cells are activated and expand in number during Borrelia infection, and this was reduced in the absence of TLR2. Furthermore, in the absence of γδ T cells, there was a significantly blunted response of adaptive immunity, as reflected in reduced expansion of T and B cells and reduced serum levels of anti-Borrelia antibodies, cytokines, and chemokines. This paralleled a greater Borrelia burden in γδ-deficient mice as well as more cardiac inflammation. These findings are consistent with a model of γδ T cells functioning to promote the adaptive immune response during infection.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease, can manifest in myriad ways in humans, among them a flulike illness, skin rash, cardiac inflammation with heart block, arthritis, and central nervous system involvement (29–34). Both innate and adaptive immunities are involved in the host defense against Borrelia infection, as witnessed by the involvement of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in response to Borrelia lipoproteins, such as the outer surface proteins (11), as well as the protective effect of antibodies (10). It is less clear how these two arms of the immune system are sequentially engaged during Borrelia infection and what cellular components might link them. In human Lyme arthritis, a clue to this may come from the appearance of a significant proportion of γδ T cells in the inflamed synovium (38, 39).

The function of γδ T cells in the immune system remains something of an enigma. Although their potential for generating a large array of T-cell receptor (TCR) rearrangements is as great as that of αβ T cells, their actual selected repertoire is more limited, suggesting that their ligand(s) may be more limited (2, 6). γδ T cells turn over in vivo at a high rate and can rapidly produce high levels of certain cytokines, such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or interleukin 17 (IL-17) (24, 35). They also express high levels of the death receptor ligand, Fas ligand (26). Collectively, these properties suggest that γδ T cells might function to either initiate and/or downregulate the adaptive immune response.

We have previously observed a strong proliferative response in vitro of γδ T cells to B. burgdorferi, both from the human Vδ1 subset that accumulates in inflamed synovium and from murine splenic γδ T cells (7, 38). In both cases, the evidence suggested that the γδ response to Borrelia was not direct but rather indirect via Borrelia stimulation of TLR, primarily TLR2, on dendritic cells (DC) (7). Of particular interest was the in vitro finding that following the indirect activation of the human synovial Vδ1 cells, they were able to further activate DC to produce IL-12 and upregulate surface costimulatory molecules (7). This suggested that certain γδ T cells might serve as a link between the innate and adaptive immune responses to B. burgdorferi infection in vivo. We therefore examined this possibility in the murine model of borreliosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infection.

Fourteen-week-old male C57BL/6J wild-type mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The breeding pair of B6.129P2-Tcrdtm1Mom/J(TCRδ−/−) and TLR2−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and bred in the animal facilities of the University of Vermont and Albany Medical Center. Mice were housed in microisolator cages according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Experiments were conducted according to IACUC-approved protocols. Low-passage cloned B. burgdorferi strain 297, with proven infectivity and pathogenicity in mice, was used throughout the studies. Spirochetes were grown in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK) complete medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 34°C to mid-log phase and then counted by dark-field microscopy using a Petroff-Hausser bacterial counting chamber. Spirochetes (106) in BSK medium were inoculated subcutaneously at the middle posterior section of the neck. Control mice received BSK medium only. Mice were euthanized after either 2 or 4 weeks of infection.

Preparation of murine γδ T cells and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells.

Spleen cells were depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis followed by negative selection to enrich for γδ T cells using rat monoclonal antibodies to CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (Tib105), B220 (RA3-6B2), major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (3F12), and CD11b (M1/70) for 30 min. The samples were washed and then incubated with goat anti-rat IgG-labeled magnetic beads (Qiagen, Inc.) for 45 min, followed by magnetic field separation. The purified cells were cultured in 48-well plates coated with 5 μg/ml of anti-TCR-γδ antibody (GL3) in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES, 2.5 mg/ml glucose [Sigma Chemical Corp., St. Louis, MO], 10 μg/ml folate [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA], 110 μg/ml pyruvate [Invitrogen], 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol [2-ME; Sigma], 292.3 μg/ml glutamine [Invitrogen], 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin [Gibco Lifesciences], and 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS]) containing 100 U/ml recombinant human IL-2. After 2 days, cells were moved to uncoated wells for further expansion with complete medium plus IL-2. On day 7, cells were used for experiments with γδ T-cell purity of >95%.

The preparation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) was done according to the method of Lutz et al. (19) and used on day 10. Cocultures of γδ T cells (1 × 106/ml) and BMDC (5 × 105/ml) were made in the absence or presence of Borrelia sonicate (25). After 18 h, supernatants were assessed for cytokine and chemokine production by the Bio-Plex assay.

B. burgdorferi-specific antibody determination.

Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (ICN Biomedical, Aurora, OH) were coated with 20 μg/ml Borrelia sonicate in bicarbonate coating buffer, pH 9.6, at 37°C for 3 h and blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 10% fetal calf serum at room temperature for 3 h. After two washes with PBS-0.05% Tween 20, serially diluted sera (from 1:100 to 1:128,000) were applied and incubated at 4°C overnight. Wells were washed six times, and biotinylated anti-immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG2a, and IgG1 (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) were applied individually and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. After six washes, the plates were incubated with avidin-peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody at room temperature for 30 min. TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) chromogenic substrate was added to all the wells after eight additional washes, and the absorbance of the plates was read at 450 nm by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (ELX 800; BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Borreliacidal activity of antibodies was determined as previously described (5). In brief, Borrelia strain 297 was grown to log phase in BSK medium at 32°C. The number of organisms was quantified by using a Petroff-Hauser counting chamber under dark-field microscopy, and 185-μl volumes of Borrelia cultures containing approximately 107 organisms per ml were added to a 500-μl Eppendorf tube. Two microliters of each mouse serum (1:100 dilution) and 13.3 μl of LOW-TOX-M rabbit complement (Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) (1:15) dilution were then added to the 200-μl total suspension. Samples were gently mixed and incubated at 32°C overnight. The number of viable organisms was then determined by the same dark-field microscopy. The growth rate was calculated for each sample by dividing the number of organisms after the overnight incubation by the number at the initiation of the incubation.

Extraction of genomic DNA from ear and bladder.

DNA was extracted from the ears or bladders of mice using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, mouse tissue was digested with 180 μl of buffer ATL and 20 μl of proteinase K at 55°C overnight. Samples were vortexed for 15 s, and 200 μl of buffer AL was added and mixed thoroughly; then 200 μl ethanol was added and mixed thoroughly. The mixture was placed in the DNeasy mini spin column and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 min. The column was washed with 500 μl buffer AW1 at 8,000 rpm for 1 min then washed with 500 μl buffer AW2 at 14,000 rpm for 3 min. The column was placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and 200 μl of buffer AE was added to the membrane for 1 min, and then the tube was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 min. (All buffers were from Qiagen.)

Quantification of B. burgdorferi recA from mouse genomic DNA by qPCR.

The copy of B. burgdorferi recA from ear and bladder was detected by real-time PCR as described before (28). The oligonucleotide primers used to detect the B. burgdorferi chromosomal recA gene were as follows: 5′-GTG GAT CTA TTG TAT TAG ATG AGG CTC TCG-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GCC AAA GTT CTG CAA CAT TAA CAC CTA AAG-3′ (reverse primer). The internal control mouse nidogen gene was amplified using the following primers: 5′-CCA GCC ACA GAA TAC CAT CC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GGA CAT ACT CTG CTG CCA TC-3′ (reverse primer). PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7700 genetic analyzer. The standard amplification program was as follows: stage 1 (1 cycle of 94°C for 2 min), stage 2 (40 cycles of three steps: 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min), and stage 3 (a three-step process for generating the dissociation curve: 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 1 min). Using this system, a threshold of 10 copies of the recA gene was detectable. The use of different amounts of ear genomic DNA from mice did not interfere with the linearity of the assay.

Serum cytokine/chemokine detection by the Bio-Plex assay.

Serum cytokine levels were detected by using the Bio-Plex assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, serum samples were diluted 1:4 by using serum sample diluent (Bio-Rad catalog no. 171305004). Fifty microliters of bead working solution was added to each well and washed two times with 100 μl of Bio-Plex wash buffer. A 50μl sample and standard were then added to wells and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with 300 rpm on an IKA MS 3 digital shaker. After three washes with 100 μl Bio-Plex wash buffer, incubation with 25 μl of detection antibody solution was done at room temperature for 30 min on the shaker. Fifty microliters of streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE in assay buffer was added to each well and incubated as described for the previous step. After an additional three washes, 150 μl of Bio-Plex assay buffer was added. Sample data were analyzed with Bio-Plex Manager software.

Histological assessment of heart and joints.

Heart and legs were collected for histological assessment by hematoxylin and eosin staining as previously described (28). Multiple serial sections of the heart were assessed to fully visualize the outflow tracts, and the cellularity and location of infiltrates were scored in a blinded fashion by a certified pathologist. An overall score was assigned to each mouse from 0 to 3 with 0.5 increments. Each ankle was assessed for synovial hyperplasia and tendonitis. An overall score was assigned from 0 to 3 with 0.5 increments.

RESULTS

Borrelia burgdorferi activates murine γδ T cells in vitro and in vivo in a TLR2-dependent fashion.

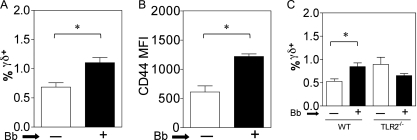

We have previously observed that bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) and B. burgdorferi can activate murine γδ T cells in vitro (7). We thus investigated whether this interaction extended to in vivo infections with Borrelia. Indeed when C57BL/6 (B6) mice were infected with B. burgdorferi strain 297, a significant increase in the proportion of γδ T cells was observed at 4 weeks in lymph nodes (Fig. 1A). This was also reflected by an increase in the surface mean fluorescence intensity of CD44 expression on γδ T cells from infected mice, consistent with their activation in vivo (Fig. 1B). Given the known ability of Borrelia lipoproteins to signal through TLR2 (11), we examined the contribution of TLR2 to the in vivo activation of γδ T cells by Borrelia. Infection of B6 wild-type and B6 TLR2−/− mice with Borrelia revealed that after 4 weeks of infection, there was an increased proportion of γδ T cells in the lymph nodes of wild-type mice, whereas no such increase was seen in the in TLR2−/− mice. In fact, a slight but not statistically significant decrease in the proportion of γδ T cells was observed during infection of TLR2−/− mice (Fig. 1C). In some though not all experiments we did observe that uninfected TLR2−/− mice manifested an increase of γδ T cells over the level in uninfected wild-type mice. The explanation for this is under further investigation, but it may represent a role for TLR2 in the known rapid turnover in vivo of γδ T cells (35).

Fig. 1.

Activation of murine γδ T cells by Borrelia burgdorferi in vivo and mutual γδ/DC activation in vitro. (A to C) C57BL/6 (B6) mice (6 mice per group) (A, B) or B6-TLR2−/− mice (C) received injections of either BSK medium alone (white bars) or 106 B. burgdorferi strain 297 organisms (Bb) (black bars), and 4 weeks later pooled cells from two brachial and two inguinal lymph nodes of each mouse were analyzed individually for the percentage of γδ T cells by flow cytometry (A) (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test). The findings were consistent in four separate experiments. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD44 expression by lymph node γδ T cells from B6 mice without or with Borrelia infection (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test). The findings were consistent in four separate experiments. (C) Comparison of the % γδ T cells in lymph nodes from B6 wild-type and B6-TLR2−/− mice (6 mice per group) following 4 weeks of infection with Borrelia (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test).

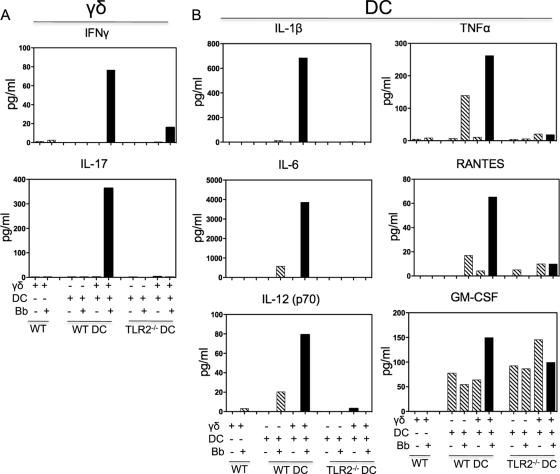

The role of TLR2 in the interaction of γδ T cells and DC was further investigated in vitro. Wild-type bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) cultured with Borrelia sonicate were able to strongly stimulate IFN-γ and IL-17 production by wild-type γδ T cells, but this was absent in cocultures of wild-type γδ T cells with TLR2−/− BMDC (Fig. 2A). Similar differences in the induction of CD25 expression by γδ T cells were previously observed (7). Furthermore, the presence of wild-type γδ T cells greatly augmented cytokine and chemokine production by Borrelia-stimulated wild-type BMDC, as exemplified by the production of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 (p70), TNF-α, and the chemokine RANTES (Fig. 2B). The synergy in the production of these cytokines and chemokine was lost when using TLR2−/− BMDC, although the production levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) by wild-type and TLR2−/− BMDC were equivalent (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Synergy of γδ T cells and bone marrow-derived DC in cytokine/chemokine production in a TLR2-dependent manner. Cocultures were made of wild-type γδ T cells and bone marrow-derived DC (DC) from either wild-type (WT) or TLR2−/− mice, in the absence or presence of Borrelia sonicate (Bb). After 48 h, supernatants from individual single wells were analyzed by the Bio-Plex assay. (A) Production of γδ T-cell cytokines IFN-γ and IL-17; (B) production of DC cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 (p70), TNF-α, GM-CSF, and the chemokine RANTES. The findings were consistent in two additional experiments.

γδ T cell-deficient mice manifest reduced adaptive immunity to Borrelia.

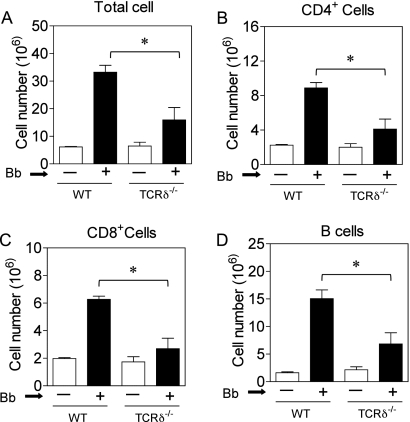

The ability of γδ T cells to augment stimulation of BMDC in vitro with Borrelia suggested that γδ T cells might contribute to the activation of the adaptive immune response in vivo during infection. We therefore examined Borrelia infection in TCRδ−/− mice. Four weeks following infection with B. burgdorferi, there was a dramatic increase in the lymph node cell number in B6 wild-type mice. Although B6 TCRδ−/− mice showed no difference in basal number or composition of lymphoid tissues, consistent with original reports (13), after infection with Borrelia we observed a substantial and statistically significant reduction in the expansion of lymph node cell number in TCRδ−/− mice compared to that in wild-type mice (Fig. 3A). This also was apparent at 2 weeks postinfection (data not shown). The effect of γδ T cells on lymphoid cell expansion was global, as there was a decrease in the number of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells in infected TCRδ−/− mice (Fig. 3B to D).

Fig. 3.

Reduced expansion of lymph node cell types during Borrelia infection of TCRδ −/− mice. Cell numbers were determined from a pool of two brachial and two inguinal lymph nodes from B6 wild-type or TCRδ−/− mice (6 mice per group) without (white bars) or with (black bars) Borrelia infection (106 per mouse) for 4 weeks. Bb, Borrelia burgdorferi. Shown are the total cell number (A), the CD4+ T-cell number (B), the CD8+ T-cell number (C), and the B-cell number (D) (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test).

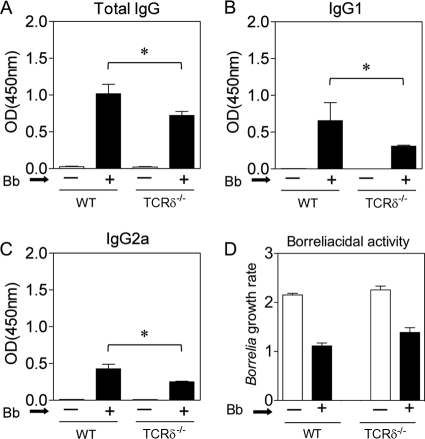

The reduced adaptive immune response also was observed in serum antibody responses to Borrelia. Neither wild-type nor TCRδ−/− uninfected mice had detectable anti-Borrelia antibodies, but 4 weeks following infection, there were robust anti-Borrelia IgG responses in mice of both genotypes (Fig. 4A). However, these were significantly reduced by 35 to 60% in the TCRδ−/− mice. This was true for both IgG1 and IgG2a responses to Borrelia (Fig. 4B and C) and paralleled the reduced expansion of B cells in response to infection in TCRδ−/− mice. Furthermore, the anti-Borrelia antibodies were actually borreliacidal, and the killing was less in sera from TCRδ−/− mice than in sera from wild-type mice, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Impaired Borrelia-specific antibody response in TCRδ −/− mice. Wild-type or TCRδ−/− mice (6 mice per group) were infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), and 4 weeks later Borrelia-specific serum antibody levels were measured by ELISA. Shown are Borrelia-specific total IgG (A), IgG1 (B), and IgG2a (C). OD, optical density. (D) Live Borrelia organisms were cultured in BSKII medium in the presence of serum (1:100) from uninfected (−) or infected (+) mice as described in Materials and Methods. Complement was added, and the organisms were cultured overnight at 32°C. The next morning, the cultures were read and the growth rate was determined by dividing the number of Borrelia organisms at the end of the culture by the number at the initiation of culture.

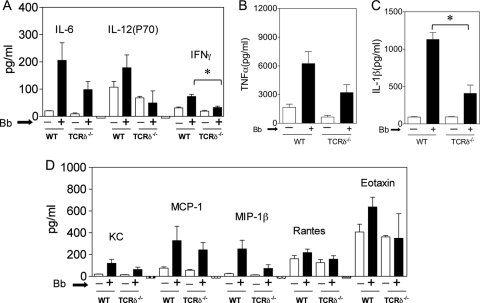

Consistent with a reduced immune response to Borrelia infection in TCRδ−/− mice, we observed a decrease in serum levels of some, although not all, cytokines and chemokines. As shown in Fig. 5, Borrelia-infected TCRδ−/− mice manifested reduced serum levels of the cytokines IL-6, IL-12(p70), IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β, as well as several chemokines (Fig. 5). This is in close agreement with the in vitro studies of synergy of cytokine/chemokine production between γδ T cells and BMDC shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 5.

Decreased serum cytokines and chemokines in TCRδ −/− mice with Borrelia infection. Serum was collected from individual wild-type or TCRδ−/− mice (6 mice per group) after 4 weeks without (white bars) or with (black bars) Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb) infection. The levels of the indicated cytokines (A to C) and chemokines (D) were determined by the Bio-Plex assay (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test). Similar findings were observed in a second experiment.

Enhanced Borrelia burden and cardiac inflammation in TCRδ−/− mice.

Given the importance of the adaptive immune response, particularly of anti-Borrelia antibodies, in the control of Borrelia infection (10), we examined the bacterial burden as well as the inflammatory response in heart and joints. Four weeks following Borrelia infection, DNA was extracted from the ears of mice and assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Borrelia burden by comparing the levels of the Borrelia chromosomal gene, recA, with levels of the murine host gene, nidogen (28). As shown in Fig. 6, TCRδ−/− mice manifested a significantly increased Borrelia burden in the ears and bladder at 4 weeks following infection. A similar trend was observed in the heart, although this did not reach statistical significance. Similar results were seen in four separate experiments.

Fig. 6.

Increased Borrelia burden in infected TCRδ−/− mice. DNA was extracted from the ear and bladder of mice at 4 weeks of infection and from hearts at 2 weeks of infection and assessed using real-time PCR for the levels of the Borrelia chromosomal gene, recA, compared to the levels of a mouse host gene, nidogen, as described in Materials and Methods (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test). The findings were consistent in four separate experiments.

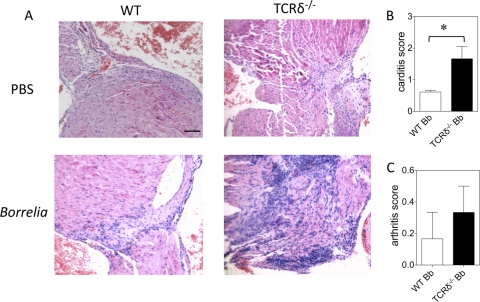

Cardiac inflammation during Borrelia infection typically occurs at the outflow tract (41). This was evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin staining of multiple serial sections (at least 10 sections per heart) through the aorta and pulmonary outflow tracts, and a composite score was determined by a pathologist blinded to the mouse genotypes. Figure 7A shows an example of the inflammatory response in wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice, which was considerably more severe in the TCRδ−/− mice. Evaluation of all mice from both genotypes revealed that the increased cardiac inflammation in TCRδ−/− mice was statistically significant (Fig. 7B). This was consistent in two additional experiments. The degree of arthritis was low to negligible in both genotypes of mice, which is typical for C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 7C). This might also reflect the older age of the mice used in these studies, since arthritis is usually most pronounced at 5 to 6 weeks of age (3). We did examine younger mice during our studies and observed similar differences in heart and joint inflammation, although these were less robust than in older mice. This may reflect a greater function of γδ T cells in older mice, or it may reflect a role of γδ T cells in the resolution of tissue inflammation more than in the initiation of inflammation.

Fig. 7.

Increased severity of carditis in TCRδ−/− mice with Borrelia infection. Wild-type (WT) or TCRδ−/− mice were infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), and 4 weeks later, hearts were assessed histologically using hematoxylin-and-eosin staining of multiple serial sections, and a global inflammation score was assigned by a pathologist blinded to the genotype of the mice. (A) Sample histology of uninfected and Borrelia-infected wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice; (B, C) composite scores of hearts (B) and joints (C) from infected mice of one of three experiments with similar results. (*, P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

The current findings demonstrate a prominent role of γδ T cells in promoting the adaptive immune response during infection with Borrelia burgdorferi and controlling the resulting bacterial burden and cardiac inflammation. The activation of γδ T cells by B. burgdorferi occurs in a TLR2-dependent manner both in vitro and in vivo. This empowers the γδ T cells with the ability to further activate DC to produce factors that can promote activation of adaptive immunity. Consistent with this model, we observed that in the absence of γδ T cells, there was a diminished adaptive immune response of both T and B cells to B. burgdorferi infection. Collectively, these results are consistent with a role of γδ T cells at the interface between the innate and adaptive immunities.

Our previous studies have shown that the activation of human γδ T cells by B. burgdorferi is indirect via the ability of Borrelia to stimulate DC via TLR, particularly TLR2 (7). The current in vivo results are in agreement with these in vitro findings and with the known ability of certain Borrelia lipopeptides and native lipoproteins to serve as TLR2 ligands (11). The actual ligand(s) for the TCR-γδ that results from Borrelia infection is under investigation, but all of the potential ligands described thus far for γδ T cells have been considerably upregulated in response to infection or cellular stress (6). Following their activation, the γδ T cells then are able to further stimulate DC to effectively express costimulatory molecules, cytokines, and chemokines necessary to enhance the adaptive immune response (7). Thus, from our in vitro findings, there is considerable mutual stimulation between DC and γδ T cells.

γδ T cells have been demonstrated to have a protective role in certain infections, such as Salmonella, Leishmania, and malaria (20, 27, 36), but they also can be pathogenic in certain autoimmunity models, such as collagen-induced arthritis, where γδ T cells drive an inflammatory response (23, 24). Conceivably, the ability of γδ T cells to augment the adaptive immune response is beneficial for clearing infections but detrimental in immune-mediated disorders. γδ T cells also have other effector functions that might make their overall effects appear complex and at times seemingly at cross-purposes. For example, both murine and human γδ T cells have been frequently reported to be highly lytic toward a wide array of targets. In this regard, we have observed that γδ T cells express high and sustained surface levels of Fas ligand (FasL) (26). This could promote killing of infected or stressed cells in one situation but also be stimulatory in another context. In fact, we have observed that human synovial Vδ1 T cells are highly lytic toward CD4 effector T cells, particularly Th2 cells, which may account for the Th1 environment of synovial CD4 T cells in Lyme arthritis (12, 38). However, the same γδ T cells also promote activation of human myeloid DC in vitro, also through FasL stimulation (8). This is because myeloid DC express high levels of the caspase-8 paralogue, c-FLIP, which inhibits caspase-8 recruitment following Fas ligation and also recruits Raf-1, TRAF2, and RIP1, adaptor proteins that link to the ERK and NF-κB pathways (9, 14, 15). This serves to divert a potential Fas death signal toward ERK and NF-κB activation (1, 8). Thus, γδ may initially promote activation of the adaptive immune response, only to rein in its activation at a later stage. In the context of Borrelia infection, it appears that the former property of augmenting adaptive immunity is the predominant effect of γδ T cells at the two time points of infection examined in this study. It is possible that at later time points or during a chronic inflammatory or autoimmune response, the predominant feature of γδ T cells might be to dampen the adaptive immune response through FasL-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4 and CD8 T cells. This may be particularly true for tissue inflammation, since this was worse in the hearts of TCRδ−/− mice.

A previous study examining the role of γδ T cells during Borrelia infection revealed a somewhat subtler phenotype than that found in our studies (4). The investigators found that BALB/c mice deficient for γδ T cells had a reduced IFN-γ response but a normal IL-4 response to Borrelia infection and as a result developed reduced IgG2a but higher IgG1 antiborrelial antibody titers. However, there was no difference in Borrelia burden, arthritis, or carditis in BALB/c TCRδ−/− mice (4). There are numerous differences between that study and ours. First, we used TCRδ−/− mice that were fully backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for more than 10 generations. We intentionally chose this background, as C57BL/6 mice manifest milder Lyme borreliosis than BALB/c or C3H strains (41). We considered that the muted response of C57BL/6 mice might provide a better opportunity to see an increase in bacterial burden and disease indices than a strain that develops more severe disease, which might already be maximal and thus unable to manifest any greater inflammation, even in the absence of γδ T cells. Second, the previous study used B. burgdorferi strain N40, whereas we used strain 297. Finally, we measured the Borrelia burden from ear DNA using qPCR of the recA gene, which is chromosomal, whereas the previous study measured ospA, which is episomal.

γδ T cells share several parallels with invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, which also respond to B. burgdorferi, although the response by iNKT cells is via direct recognition of borrelial diacylglycerol antigens in a CD1d-restricted manner (17, 37, 40). Nonetheless, both γδ and iNKT cell subsets rapidly produce various cytokines in response to infection (18, 42), both manifest a previously activated phenotype in vivo as reflected in CD44 expression and a high turnover rate (16, 35), and there is evidence in both for their indirect activation via TLR signaling on DC, which may enable the γδ and iNKT cells to better activate both innate and adaptive immune responses (8, 21, 22). Like γδ T-cell-deficient mice, iNKT-deficient mice have a reduced ability to clear Borrelia upon infection (37). Thus, both γδ T cells and iNKT cells may function as transitional T cells that link the innate and adaptive immune responses. As such, they also may have somewhat overlapping functions in the immune response to infection. Given this possible redundancy, it will be of interest to examine infections in the absence of both iNKT and γδ T cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AR43520, AI45666, AI36333, and AI054546.

We thank Colette Charland for technical assistance with flow cytometry, Janice Bunn for statistical analysis, and Timothy Hunter at the Vermont Cancer Center for assistance with qPCR.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashany D., Savir A., Bhardwaj N., Elkon K. B. 1999. Dendritic cells are resistant to apoptosis through the Fas (CD95/APO-1) pathway. J. Immunol. 163:5303–5311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aydintug M. K., et al. 2004. Detection of cell surface ligands for the gamma delta TCR using soluble TCRs. J. Immunol. 172:4167–4175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barthold S. W., Beck D. S., Hansen G. M., Terwilliger G. A., Moody K. D. 1990. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J. Infect. Dis. 162:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bockenstedt L. K., Shanafelt M. C., Belperron A., Mao J., Barthold S. W. 2003. Humoral immunity reflects altered T helper cell bias in Borrelia burgdorferi-infected gamma delta T-cell-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 71:2938–2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callister S. M., Schell R. F., Lovrich S. D. 1991. Lyme disease assay which detects killed Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1773–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chien Y. H., Jores R., Crowley M. P. 1996. Recognition by gamma/delta T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14:511–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins C., Shi C., Russell J. Q., Fortner K. A., Budd R. C. 2008. Activation of gamma delta T cells by Borrelia burgdorferi is indirect via a TLR- and caspase-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 181:2392–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins C., et al. 2005. Lyme arthritis synovial gamma delta T cells instruct dendritic cells via fas ligand. J. Immunol. 175:5656–5665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dohrman A., et al. 2005. Cellular FLIP (long form) regulates CD8+ T cell activation through caspase-8-dependent NF-kappa B activation. J. Immunol. 174:5270–5278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fikrig E., Barthold S. W., Kantor F. S., Flavell R. A. 1990. Protection of mice against the Lyme disease agent by immunizing with recombinant OspA. Science 250:553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirschfeld M., et al. 1999. Cutting edge: inflammatory signaling by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 163:2382–2386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huber S., Shi C., Budd R. C. 2002. γδ T cells promote a Th1 response during coxsackievirus B3 infection in vivo: role of Fas and Fas ligand. J. Virol. 76:6487–6494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Itohara S., et al. 1993. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell 72:337–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kataoka T., et al. 2000. The caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP promotes activation of NF-kappaB and Erk signaling pathways. Curr. Biol. 10:640–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kataoka T., Tschopp J. 2004. N-terminal fragment of c-FLIP(L) processed by caspase 8 specifically interacts with TRAF2 and induces activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:2627–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawano T., et al. 1997. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science 278:1626–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kinjo Y., et al. 2006. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 7:978–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee Y. K., et al. 2009. Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity 30:92–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lutz M. B., et al. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mixter P. F., Camerini V., Stone B. J., Miller V. L., Kronenberg M. 1994. Mouse T lymphocytes that express a gamma delta T-cell antigen receptor contribute to resistance to Salmonella infection in vivo. Infect. Immun. 62:4618–4621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Montoya C. J., et al. 2006. Activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with TLR9 agonists initiates invariant NKT cell-mediated cross-talk with myeloid dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 177:1028–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Paget C., et al. 2007. Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity 27:597–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peterman G. M., Spencer C., Sperling A. I., Bluestone J. A. 1993. Role of gamma delta T cells in murine collagen-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 151:6546–6558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roark C. L., et al. 2007. Exacerbation of collagen-induced arthritis by oligoclonal, IL-17-producing gamma delta T cells. J. Immunol. 179:5576–5583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roessner K., et al. 1994. Prominent T lymphocyte response to Borrelia burgdorferi from peripheral blood of unexposed donors. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roessner K., et al. 2003. High expression of Fas ligand by synovial fluid-derived gamma delta T cells in Lyme arthritis. J. Immunol. 170:2702–2710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosat J. P., MacDonald H. R., Louis J. A. 1993. A role for gamma delta+ T cells during experimental infection of mice with Leishmania major. J. Immunol. 150:550–555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shi C., et al. 2006. Fas ligand deficiency impairs host inflammatory response against infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 74:1156–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steere A. C. 1989. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 321:586–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steere A. C., et al. 1983. The early clinical manifestations of Lyme disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 99:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steere A. C., Duray P. H., Butcher E. C. 1988. Spirochetal antigens and lymphoid cell surface markers in Lyme synovitis: comparison with rheumatoid synovium and tonsillar lymphoid tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 31:487–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steere A. C., Dwyer E., Winchester R. 1990. Association of chronic Lyme arthritis with HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR2 alleles. N. Engl. J. Med. 323:219–223 [Erratum, 324(2):129, 1991.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steere A. C., et al. 1983. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:733–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steere A. C., Schoen R. T., Taylor E. 1987. The clinical evolution of Lyme arthritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 107:725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tough D. F., Sprent J. 1998. Lifespan of gamma/delta T cells. J. Exp. Med. 187:357–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsuji M., et al. 1994. Gamma delta T cells contribute to immunity against the liver stages of malaria in alpha beta T-cell-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:345–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tupin E., et al. 2008. NKT cells prevent chronic joint inflammation after infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:19863–19868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vincent M., et al. 1996. Apoptosis of Fas high CD4+ synovial T cells by Borrelia reactive Fas ligand high gamma delta T cells in Lyme arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 184:2109–2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vincent M. S., et al. 1998. Lyme arthritis synovial gamma delta T cells respond to Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and lipidated hexapeptides. J. Immunol. 161:5762–5771 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang J., et al. 2010. Lipid binding orientation within CD1d affects recognition of Borrelia burgorferi antigens by NKT cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1535–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weis J. J. 2002. Host-pathogen interactions and the pathogenesis of murine Lyme disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 14:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wu D., et al. 2005. Bacterial glycolipids and analogs as antigens for CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:1351–1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]