Abstract

We recently reported an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in the major heart surgery unit of Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain (T. Peláez, P. Muñoz, J. Guinea, M. Valerio, M. Giannella, C. H. W. Klaassen, and E. Bouza, Clin. Infect. Dis., in press). Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated from clinical samples from 10 patients admitted to the unit during the outbreak period (surgical wound invasive aspergillosis, n = 2; probable pulmonary invasive aspergillosis, n = 4; colonization, n = 4). In the study described here, we have studied the genotypic diversity of the A. fumigatus isolates found in the air and clinical samples. We used short tandem repeats of A. fumigatus (STRAf) typing to analyze the genotypes found in the 168 available A. fumigatus isolates collected from the clinical samples (n = 109) from the patients and from the environmental samples taken from the air of the unit (n = 59). The genotypic variability of A. fumigatus was higher in environmental than in clinical samples. Intrasample variability was also higher in environmental than in clinical samples: 2 or more different genotypes were found in 26% and 89% of clinical and environmental samples, respectively. We found matches between environmental and clinical isolates in 3 of the 10 patients: 1 patient with postsurgical invasive aspergillosis and 2 patients with probable pulmonary invasive aspergillosis. A total of 7 genotypes from 3 different patients and the air grouped together in 2 clusters. Clonally related genotypes and microvariants were detected in both clinical and environmental samples. STRAf typing proved to be a valuable tool for identifying the source of invasive aspergillosis outbreaks and for studying the genotypic diversity of clinical and environmental A. fumigatus isolates.

INTRODUCTION

Most cases of invasive aspergillosis are caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, whose conidia are ubiquitous in outdoor and hospital air (4, 15, 24). Invasive aspergillosis occurs when airborne conidia invade exposed tissue, particularly the lungs and surgical wounds.

The presence of activities such as construction work in or near the hospital correlates with an increase in the number of new cases of invasive aspergillosis (30). Conversely, the implementation of procedures to minimize airborne spore loads correlates with a decrease in the incidence of invasive aspergillosis (7). However, in order to demonstrate that airborne conidia are infecting or colonizing patients, both environmental and clinical isolates must be genotyped.

Previous studies have shown a high genotypic diversity of A. fumigatus in the air. However, these studies are limited by the use of typing tools with low reproducibility, analysis of genotypic variability limited to samples from the air, and genotyping of clinical or environmental isolates but rarely both (19–22, 31). Short tandem repeat procedures feature high reproducibility and easy analysis of the results.

We recently reported an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in the major heart surgery unit of Hospital Gregorio Marañón coinciding with periods of construction work nearby (23). In the outbreak, 6 of the patients involved were infected by A. fumigatus. During this period, we collected environmental air samples from the unit and demonstrated that high counts of Aspergillus conidia in air correlated with the appearance of new cases of invasive aspergillosis. We used a recently developed highly discriminatory and reproducible typing tool, short tandem repeats of A. fumigatus (STRAf) (12), to perform extensive and refined genotyping of the strains isolated from the air of the unit and from the clinical samples of patients involved in the outbreak and to study the A. fumigatus genotypic diversity. An additional analysis of environmental and clinical isolates not geographically or temporally related to those taken from the major heart surgery unit during the outbreak allowed us to demonstrate the high variability of this mold in hospital air.

(This study was presented in part at the 19th European Congress on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases [ECCMID], Helsinki, Finland, 2009 [23].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and clinical samples.

We studied 10 consecutive patients whose clinical samples yielded A. fumigatus and who were admitted to the major heart surgery intensive care unit of Hospital Gregorio Marañón from December 2006 to May 2008 (outbreak period). According to the revised European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer definitions (10), the patients had proven invasive aspergillosis (surgical wound infection, n = 2), probable invasive aspergillosis (pulmonary infection, n = 4), or colonization (pulmonary or surgical wound colonization, n = 4). Further details of these criteria are described in a forthcoming publication by Peláez et al. (23a). Patients were numbered chronologically in order of admission to the unit. Additionally, 5 patients located in other wards (during or before the outbreak) with proven invasive aspergillosis (pulmonary invasion, n = 1; prostate invasion, n = 1) or pulmonary colonization (n = 3) were included as controls.

A total of 40 clinical samples were studied and included bronchial aspirate (n = 21), sputum (n = 5), mediastinal surgical wound (n = 12), bone biopsy (n = 1), and prostatic biopsy (n = 1) samples; 35 of these were from patients admitted to the unit during the outbreak. Clinical samples were obtained when indicated and cultured both in fungal media and in conventional media. Fungal cultures were incubated at 35°C for no fewer than 7 days. Each colony of A. fumigatus isolated on the plates was subcultured and stored independently.

Environmental samples.

We studied all available isolates from a total of 77 environmental samples collected from the air of the unit during the outbreak period (n = 30) or from other hospital wards. Each A. fumigatus colony isolated from the plates of the samples taken in the unit during the outbreak was also subcultured and stored independently. In air samples taken from other hospital locations, 1 A. fumigatus colony per plate was available for genotyping.

Air samples were collected using a Merck MAS 100 air sampler, drawing a final air volume of 200 liters per sample onto Sabouraud dextrose irradiated agar plates that were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at 35°C for 5 days.

Fungal isolation and identification.

All available A. fumigatus strains were identified according to conventional morphological procedures and stored in tubes containing sterile distilled water at room temperature for further genotyping.

DNA extraction.

The strains were cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar before analysis to ensure the purity of the A. fumigatus isolates before DNA extraction. Plates were incubated at 35°C until sporulation. Aspergillus DNA was extracted and purified with a MagNA Pure LC instrument (Roche Diagnostics) according to previously described protocols (13).

Genotyping procedure.

All strains were genotyped using the STRAf assay developed by de Valk et al. (12). This technique is based on analysis of 9 short tandem repeat markers that are amplified by 3 multiplex PCRs (M2, M3, and M4). Electropherograms were analyzed using Fragment Profiler (version 1.2) software (GE Healthcare). DNA preparations with mixtures of genotypes were excluded from the analysis. Typing data were imported into BioNumerics (version 6.0.1) software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) and analyzed using the multistate categorical similarity coefficient. Genotypic diversity was represented graphically using a minimum spanning tree.

Genotypic variability and environmental and clinical genotype matches.

We studied the number of different environmental and clinical genotypes found in the air and clinical samples collected. To study genotypic variability, we selected only those strains isolated from the unit during the outbreak. Furthermore, to study intrasample variability, we selected only those environmental or clinical samples from which 2 or more A. fumigatus colonies were isolated.

To study the genotypic diversity of A. fumigatus found in the air and clinical samples, we chose only 1 random colony from each sample (n = 117). We calculated Simpson's index of diversity (D), where N is the total number of isolates in the test population, s is the total number of different genotypes described, and nj is the number of isolates belonging to the jth type (25).

Genotypes were considered identical (identical alleles for all 9 loci), clonally related (microvariants; having differences of no more than 2 repeat units in a single locus), or unrelated (when they had a total of 3 or more repeat units different) (definitions are adapted from reference 3). Environmental and clinical isolates were considered a match when identical genotypes or microvariants were found.

RESULTS

Genotypic variability in environmental and clinical samples.

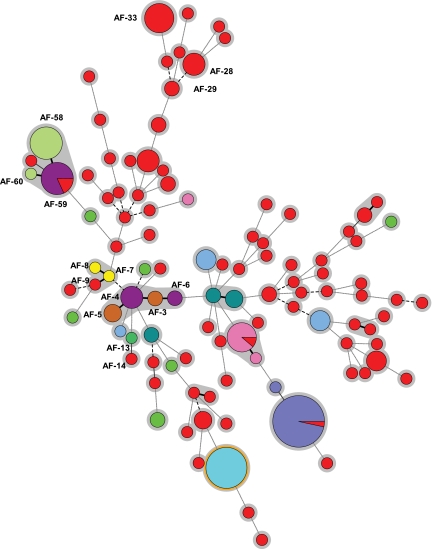

A total of 223 isolates from 117 different samples were analyzed, and 105 different genotypes were found. The minimum spanning tree showed high genotypic variability among the isolates studied (Fig. 1). Overall genotypic diversity was 0.984; in other words, there is a 1.6% chance that any 2 randomly chosen isolates are of the same genotype, which is well below the proposed cutoff of 5% proposed by van Belkum et al. (29).

Fig. 1.

Minimum spanning tree showing wide genotypic diversity in the strains studied. The figure shows the 105 different genotypes found (circles), the number of strains belonging to the same genotype (sizes of the circles), and the source of the isolates (circles in red indicate environmental isolates; other colors represent individual patients [n = 10]). Connecting lines between circles show the similarity between profiles: solid and bold indicate differences in only 1 marker, a solid line indicates differences in 2 markers, long dashes indicate differences in 3 markers, and short dashes indicate differences in 4 or more markers. The genotypes mentioned in the text are indicated (AF-xx). Clonally related genotypes (microvariants) are connected by a solid, bold line.

We studied genotypic variability among 168 isolates collected during the outbreak (environmental [n = 59] and clinical [n = 109]) and identified 62 different genotypes. Although the number of clinical isolates studied exceeded the number of environmental isolates, the proportion of different genotypes was higher in the air samples (71.2%) than in the clinical samples (20.2%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

A. fumigatus genotypes found in air and in clinical samples collected and studied during the outbreak

| Sample source | No. of samples | No. of isolates | No. of different genotypesa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 30 | 59 | 42 |

| Clinical | 35 | 109 | 22 |

| Total | 65 | 168 | 62 |

Different but clonally related genotypes (microvariants) were counted as one genotype.

To study the number of different genotypes found in each clinical and environmental sample, we selected only those samples in which 2 or more A. fumigatus strains were isolated (n = 36). In samples with multiple A. fumigatus colonies, the probability of finding more than 1 different genotype was higher in environmental samples (89%) than in clinical samples (26%). No more than 2 different genotypes were found in the clinical samples. In contrast, 3, 7, and 8 different genotypes were found in 3 of the 9 environmental samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of intrasample genotypic variability of Aspergillus fumigatus in the 36 samples in which 2 or more A. fumigatus colonies were isolated

| No. of isolates per sample | No. (%) of samplesa |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental |

Clinical |

|||||||

| Total | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | Total | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | |

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 | |||||

| ≥5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Total | 9 | 1 (11.1) | 5 (55.5) | 3 (33.3) | 27 | 20 (74.1) | 7 (25.9) | 0 |

Numbers of samples containing 1, 2, or ≥3 different or clonally related A. fumigatus genotypes (microvariants) are shown.

Presence of matches between clinical and environmental isolates.

We found a match between environmental and clinical isolates in 3 patients. Environmental and clinical matches were identical (patient 1 and patient 5) or clonally related (patient 7) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnoses of the 10 patients, clinical samples with isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus, and number of different genotypes founda

| Patient | Diagnosis | No. of days of admission to unit | Clinical samples |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | No. | No. of different genotypes | Genotype matching environmental genotype | |||

| 1 | Proven surgical wound IAb | 31 | Surgical wound (n = 8), bone biopsy specimen | 9 | 2 | Yes |

| 2 | Probable pulmonary IA | 33 | Bronchial aspirate (n = 4), protected brush catheter | 5 | 1 | No |

| 3 | Pulmonary colonization | 10 | Bronchial aspirate | 3 | 4 | No |

| 4 | Pulmonary colonization | 18 | Bronchial aspirate | 1 | 2 | No |

| 5 | Probable pulmonary IA | 12 | Bronchial aspirate | 4 | 3 | Yes |

| 6 | Pulmonary colonization | 34 | Bronchial aspirate | 1 | 1 | No |

| 7 | Probable pulmonary IA | 79 | Bronchial aspirate | 3 | 2 | Yes |

| 8 | Probable pulmonary IA | 5 | Sputum (n = 3), bronchial aspirate, protected brush catheter | 5 | 3 | No |

| 9 | Proven surgical wound IA | 83 | Surgical wound | 3 | 3 | No |

| 10 | Surgical wound colonization | 50 | Surgical wound | 1 | 1 | No |

The presence of matches between environmental and clinical genotypes is also shown. Patients with proven/probable invasive aspergillosis are highlighted with shading.

IA, invasive aspergillosis.

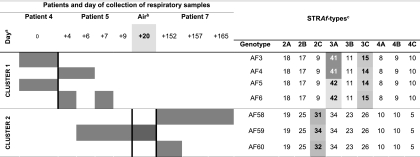

Some findings were interesting in clonal terms and are summarized below. Patient 1 developed invasive aspergillosis in a mediastinal surgical wound. Two different genotypes were identified. The one from the wound samples matched an air genotype found 5 days before the first isolation of clinical A. fumigatus. The other genotype was isolated from a confirmatory sternal bone biopsy specimen (histologically proven invasive aspergillosis) and differed from the first genotype in markers 3A (a difference of 6 repeats) and 3B (a difference of 3 repeats). Patients 4, 5, and 7 presented the most complex molecular epidemiology findings of the study (Fig. 2). We found 3 different genotypes (AF4, AF6, and AF59) in patient 5, who developed probable pulmonary invasive aspergillosis. AF4 and AF6 were clonally related to the 2 genotypes isolated in a respiratory sample from patient 4 (AF3 and AF5). These 4 genotypes comprised a group of microvariants differing in markers 3A or 3C by only 1 repeat unit (cluster 1 in Fig. 2). The remaining genotype found in patient 5 (AF59) matched an air genotype and was clonally related to the 2 genotypes found in patient 7 (AF58 and AF60). This patient developed pulmonary invasive aspergillosis and was admitted to the unit some months after the discharge of patient 5. This group of genotypes comprised another group of microvariants differing only in marker 2C by 1 or 2 repeat units (cluster 2 in Fig. 2). There were genotypes matching among the patients only for patients 4 and 5 and for patients 5 and 7 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Genotypes of Aspergillus fumigatus found in the samples of patients 4, 5, and 7. The figure also shows the A. fumigatus genotypes found in the air that matched the clinical isolates of patients 5 and 7. Gray squares indicate the day(s) on which the genotypes were found. a, day 0 refers to the day on which A. fumigatus was isolated for the first time in the respiratory samples of patient 4; also indicated is the number of days from day 0 to the time of isolation of A. fumigatus in the clinical samples of patient 5, patient 7, and the air of the unit; b, air samples yielding an environmental genotype that matched the clinical genotypes of patient 5 and patient 7; c, numbers correspond to the observed number of tandem repeats in each marker.

Persistence and geographic distribution of environmental genotypes in hospital air.

The inclusion of control isolates collected from other hospital wards at different times allowed us to study whether a genotype could be found at different sites or at the same site at different times. Most environmental genotypes (39 out of the 42 different genotypes) were detected at a single site in ≤4 days. Nevertheless, 3 genotypes persisted for a long period or were found in different hospital wards. Genotype AF29, which was found in the air of the unit during the outbreak, had been detected at another hospital site 8 months before. Genotype AF33 was detected in the air of the unit in November 2007 and May 2008; it was found again in 7 different rooms of the hospital in August 2008. Genotype AF28 was present only in the air of the unit but was detected 5 times in a period of 13 days.

DISCUSSION

Although uncommon, nosocomial outbreaks of invasive aspergillosis are problematic, due to the high mortality of the patients affected. In most cases, the sources of the conidia causing the outbreak are the presence of construction work in the hospital or nearby and malfunctioning air-conditioning systems (30). However, genotyping of both clinical and environmental isolates is necessary to demonstrate that airborne conidia have caused the infection.

Different procedures have been used to genotype A. fumigatus, including random amplified polymorphic DNA, interrepeat PCR, amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis, restriction fragment length polymorphism, multilocus sequence typing (2, 16, 27, 28), and short tandem repeats (6, 12, 14, 26). Procedures based on short tandem repeats (such as the STRAf assay) seem to provide the highest discriminatory power, unambiguous assignment of the genotypes, and a high interlaboratory exchangeability of results (11).

Despite the many advantages of the STRAf assay and its ability to clarify the source of nosocomial invasive aspergillosis outbreaks, it has rarely been used to type clinical and environmental samples. Kidd et al. (17) studied the isolates involved in an invasive aspergillosis outbreak in the hematology unit, although only 3 clinical isolates and 8 environmental isolates were analyzed and air samples were collected only after diagnosis of the third case. Balajee et al. (3) validated STRAf as a valuable tool to support epidemiological investigation of invasive aspergillosis outbreaks. However, their retrospective analysis did not specify their methodology, and it is possible that they were unable to separate colonies from plates, thus restricting the detection of possible genotypic variability. We studied the clinical and environmental A. fumigatus genotypes involved in an invasive aspergillosis outbreak occurring in our major heart surgery unit. At Hospital Gregorio Marañón, we conduct systematic monthly surveillance to search for the presence of filamentous fungi in this unit. The frequency of sampling was increased during the outbreak, allowing us to screen for the presence of environmental genotypes recently involved in the infection. We also independently stored all A. fumigatus colonies found in the available clinical and environmental samples collected.

We observed high genotypic variability in the environmental samples. Previous studies using other genotyping procedures reached the same conclusion (5, 8, 9, 18, 19). Genotypic variability was higher in air samples than in clinical samples. A potential explanation is that environmental genotypes not efficiently adapted to the host tissues are not selected. It is also possible that the high number of clinical isolates studied may have led us to underestimate diversity in the clinical samples. However, intrasample analysis showed that, in samples containing 2 or more A. fumigatus isolates, the presence of different genotypes was more common in environmental samples. Our study confirms observations by de Valk et al. (13), who reported that most patients were infected by only 1 genotype or colonized by 1 or 2 genotypes.

Demonstration of clinical and environmental matches is important to prove an environmental source of the outbreak and nosocomial acquisition of the infection. Although we found an environmental match in only 3 out of the 10 patients studied, we cannot exclude the possibility of the presence of environmental matches in another 3 patients, because the air was not sampled during their stay in the unit. This small number of matches probably reflects a high diversity of isolates in air, thus making it difficult to interpret our results, because the isolates in air samples cannot be representative of the biodiversity existing in the environment. The high genotypic diversity of airborne A. fumigatus can even decrease the probability of finding clinical and environmental matches. Moreover, the inclusion of more environmental isolates would considerably increase the workload of the clinical microbiology laboratory. From this perspective, improved low-cost fast genotyping methods yielding unambiguous genotyping data are necessary.

Interpretation and definition of microvariants or clonally related isolates remain controversial, and adoption of arbitrary definitions complicates the interpretation of data. The definition of microvariants was useful to prove environmental and clinical matches in patient 7. However, if other less restrictive definitions of microvariants had been chosen, we would have defined additional environmental and clinical matches for patient 6 (AF13 and AF14) and patient 10 (AF7, AF8, and AF9), although the environmental isolates would not have been collected from the air of the unit. We found microvariants in the clinical samples of patients 3, 7, 9, and 10, suggesting that their presence is common in the clinical samples of patients infected or colonized by A. fumigatus. Clusters 1 and 2 are particularly interesting, as they reveal the coexistence of clonally related genotypes in the clinical samples of 3 different patients who were sequentially admitted to the unit during the outbreak period. Previous studies have shown that microvariants are also common in hospital air (1). Further studies should demonstrate whether these microvariants are present in the air only or whether they may also have a role in the adaptation of isolates to host tissues. The 2 clinical genotypes of patient 1 did not fulfill our definition of microvariant and should be considered unrelated genotypes.

We found that some genotypes persist in hospital air for long periods or can be found in different parts of the hospital, as reported elsewhere (1, 6, 9). The presence of genotypes in different parts of the hospital complicates analysis of the results and should be considered a limitation of genotyping for an epidemiological investigation of outbreaks of invasive aspergillosis. For example, 3 different clinical genotypes were found in patient 9, who developed invasive Aspergillus surgical wound infection after major heart surgery. During the outbreak, one genotype was also found in the air at a part of the hospital the patient had never visited, suggesting that this genotype could be circulating in different parts of the hospital. We cannot exclude the possibility that this genotype could have been detected in the air of the unit if more environmental isolates had been included.

In conclusion, using refined sampling of multiple colonies and STRAf-based genotyping, we were able to detect the presence of environmental matches for 3 patients involved in a nosocomial outbreak of invasive aspergillosis. We also demonstrated the high genetic diversity of A. fumigatus in the environment. Finally, we observed that the presence of microvariants was common in clinical samples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas O'Boyle for editing and proofreading the article.

This study does not present any conflicts of interest for its authors.

This study was partially financed by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) PI070198 (Instituto de Salud Carlos III). Jesús Guinea is contracted by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) CP09/00055. Pilar Escribano is contracted by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) CD09/00230. Jesús Guinea received a travel grant from ESCMID.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Araujo R., Amorim A., Gusmao L. 2010. Genetic diversity of Aspergillus fumigatus in indoor hospital environments. Med. Mycol. 48:832–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bain J. M., et al. 2007. Multilocus sequence typing of the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1469–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balajee S. A., de Valk H. A., Lasker B. A., Meis J. F., Klaassen C. H. 2008. Utility of a microsatellite assay for identifying clonally related outbreak isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Microbiol. Methods 73:252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balajee S. A., et al. 2009. Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3138–3141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bart-Delabesse E., Cordonnier C., Bretagne S. 1999. Usefulness of genotyping with microsatellite markers to investigate hospital-acquired invasive aspergillosis. J. Hosp. Infect. 42:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bart-Delabesse E., Humbert J. F., Delabesse E., Bretagne S. 1998. Microsatellite markers for typing Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2413–2418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benet T., et al. 2007. Reduction of invasive aspergillosis incidence among immunocompromised patients after control of environmental exposure. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:682–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bertout S., et al. 2001. Genetic polymorphism of Aspergillus fumigatus in clinical samples from patients with invasive aspergillosis: investigation using multiple typing methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1731–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chazalet V., et al. 1998. Molecular typing of environmental and patient isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus from various hospital settings. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1494–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Pauw B., et al. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1813–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Valk H. A., et al. 2009. Interlaboratory reproducibility of a microsatellite-based typing assay for Aspergillus fumigatus through the use of allelic ladders: proof of concept. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:180–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Valk H. A., et al. 2005. Use of a novel panel of nine short tandem repeats for exact and high-resolution fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4112–4120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Valk H. A., Meis J. F., de Pauw B. E., Donnelly P. J., Klaassen C. H. 2007. Comparison of two highly discriminatory molecular fingerprinting assays for analysis of multiple Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from patients with invasive aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1415–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Valk H. A., Meis J. F., Klaassen C. H. 2007. Microsatellite based typing of Aspergillus fumigatus: strengths, pitfalls and solutions. J. Microbiol. Methods 69:268–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guinea J., Peláez T., Alcalá L., Bouza E. 2006. Outdoor environmental levels of Aspergillus spp. conidia over a wide geographical area. Med. Mycol. 44:349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khan Z. K., et al. 1998. Aspergillus fumigatus strains recovered from immunocompromised patients (ICP): subtyping of strains by RAPD analysis. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 46:537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kidd S. E., et al. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis: lessons learned from an outbreak investigation in an Australian hematology unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 30:1223–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lair-Fulleringer S., et al. 2003. Differentiation between isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus from breeding turkeys and their environment by genotyping with microsatellite markers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1798–1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leenders A., et al. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of apparent outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in a hematology ward. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:345–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loudon K. W., Burnie J. P., Coke A. P., Matthews R. C. 1993. Application of polymerase chain reaction to fingerprinting Aspergillus fumigatus by random amplification of polymorphic DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1117–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mellado E., et al. 2000. Characterization of a possible nosocomial aspergillosis outbreak. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neuveglise C., Sarfati J., Latge J. P., Paris S. 1996. Afut1, a retrotransposon-like element from Aspergillus fumigatus. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1428–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peláez T., et al. 2009. Outbreak of invasive aspergillosis in an intensive care unit (ICU) for major heart surgery (MHS). The case for abnormally high levels of airborne Aspergillus conidia: presence of similar genotypes in air and clinical samples, abstr. O-244. Abstr. 19th Eur. Congr. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 23a. Peláez T., et al. Clin. Infect. Dis., in press [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perdelli F., et al. 2006. Fungal contamination in hospital environments. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 27:44–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simpson E. H. 1949. Measurement of diversity. Nature 163:688 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thierry S., et al. 2010. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis for molecular typing of Aspergillus fumigatus. BMC Microbiol. 10:315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Trevino-Castellano M., et al. 2003. Combined used of RAPD and touchdown PCR for epidemiological studies of Aspergillus fumigatus. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 21:472–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Belkum A., Quint W. G., de Pauw B. E., Melchers W. J., Meis J. F. 1993. Typing of Aspergillus species and Aspergillus fumigatus isolates by interrepeat polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2502–2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Belkum A., et al. 2007. Guidelines for the validation and application of typing methods for use in bacterial epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(Suppl. 3):1–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vonberg R. P., Gastmeier P. 2006. Nosocomial aspergillosis in outbreak settings. J. Hosp. Infect. 63:246–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Warris A., et al. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates recovered from water, air, and patients shows two clusters of genetically distinct strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4101–4106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]