Abstract

Multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) was compared to multilocus sequence typing (MLST) to differentiate hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains. Although MLVA—like MLST—was highly discriminatory (index of diversity, 0.988 versus 0.984), a low level of concordance demonstrated the limited ability of MLVA to reflect long-term evolutionary events.

TEXT

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) strains belong to the Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) group and can cause severe illness, ranging from watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (9). To study the phylogeny of EHEC and the pathogenesis of HUS, the Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome-associated Escherichia coli (HUSEC) collection, which includes all EHEC serotypes known to be associated with HUS, was recently established (14). In addition to the characterization of the pathogenicity of these strains, the molecular phylogeny has been determined using multilocus sequence typing (MLST), revealing a high diversity of sequence types (STs) and an association of STs and serogroups in Germany (14). MLST is based on DNA sequence analysis of (usually) five to seven housekeeping genes (13) and in the past decade has become a common standard for use in elucidating the phylogeny of bacterial and fungal species (2). MLST alone is not sufficient, however, to further discriminate closely related strains, to confirm or exclude outbreaks or transmissions, for example. To elucidate such situations, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) emerged as the common standard (7, 20). However, despite its high discriminatory power, PFGE can be problematic due to certain intra- and interlaboratory reproducibility aspects (16). Therefore, alternative highly discriminatory molecular methods, including multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA), have emerged (4). The molecular basis of this approach is the determination of the number of tandem repeats found mostly in noncoding genome segments (21). Combinations of the repeat numbers from (usually) six to 10 different repeat regions distributed over the chromosome are then used for strain comparisons. This method has become a well-established typing tool, especially for monomorphic organisms such as EHEC O157:H7/H−, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Bacillus anthracis (5, 7, 12, 17, 19). Initially, the use of MLVA was frequently restricted to certain species or serotypes (e.g., EHEC O157:H7/H−) (7, 12, 17), which limited the broader use of MLVA schemes. To overcome this drawback, a serotype-independent E. coli MLVA scheme suitable even for other closely related genera (e.g., Shigella) was developed (11). Here, we evaluated the ability of this pan-E. coli MLVA scheme to differentiate the strains in the HUSEC collection and compared the results with those of MLST and serotyping.

The pan-E. coli MLVA analysis of the 42 strains of the HUSEC collection (14) was performed as outlined by Lindstedt et al. to determine the number of repeats in the seven loci CVN001, CVN002, CVN003, CVN004, CVN007, CVN014, and CVN015 (11), which are all located in protein-encoding regions of E. coli reference strain EDL933 (GenBank accession no. NC_002655). A null allele (“0”) was assigned when no amplicon was detected. EpiCompare software (Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany) was used to determine the typeability and discriminatory power of MLVA. The discriminatory power represented by the index of diversity (ID) value quantifies the ability of a method to differentiate between very similar strains that were randomly sampled in a population (6). Moreover, the MLVA results were compared to MLST data from a study by Mellmann et al. (14) to determine the level of concordance. Evaluation of the clustering concordance was performed using Adjusted Rand and Wallace indices with Phyloviz software (http://www.phyloviz.net/beta/) (1).

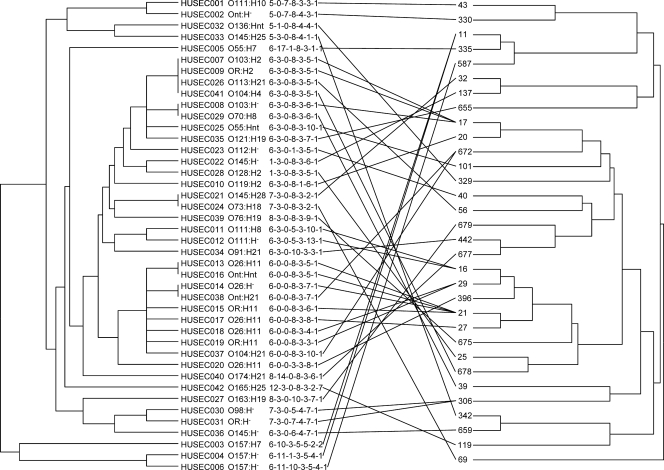

The 42 HUSEC strains exhibited 35 unique MLVA profiles, resulting in an overall ID of 0.988. MLVA profile 6-3-0-8-3-5-1, present in four strains, was the most common. Thirty profiles were identified only once (Fig. 1). Detailed characteristics of the VNTR loci revealed 3 (CVN015) to 11 (CVN014) different alleles. ID values ranged from 0.094 (CVN015) to 0.899 (CVN014). Null alleles with either no fragment or a fragment far beyond the detected sizes (100 to 700 bp in length) were present in two of the seven analyzed loci, CVN002 and CVN003, with frequencies of 28.6% and 85.7%, respectively. Those two repeat regions were located within genes encoding hypothetical proteins. This resulted in typeability values that ranged from 14.3% to 100% for all loci. Interestingly, all HUSEC isolates from serogroup O26 and all O-nontypeable (Ont) isolates exhibited null alleles in locus CVN002. In general, the results determined by the applied MLVA scheme corroborate the findings of great diversity among the serotypes and are comparable to the MLST results (ID, 0.984 with 32 different STs [14]). However, the high null allele frequency (85.7%) of CVN003 means that that locus is probably not useful for determinations involving strains from this collection, whereas the null allele frequency of CVN002 is comparable to the frequency seen in other studies (7, 8). None of the O26 isolates were typeable using these loci, exhibiting a MLVA profile with five conserved VNTR loci (6-0-0-X-3-X-1) and thus suggesting a specific feature for this serogroup. Extended analysis of serogroup O26 corroborated the frequent absence of locus CVN003 (15); however, it might serve as part of an EHEC serogroup verification by supplementing antibody-based methods (18). Moreover, those loci encoding hypothetical proteins (based on EDL933 genome data) exhibited null alleles, suggesting a serogroup-specific function or no function at all.

Fig. 1.

Tanglegram illustrating the topology of UPGMA trees based on MLVA patterns (left) and MLST sequence types (STs; right). The corresponding HUSEC strain number is followed by its specific serotype and its MLVA pattern as follows: CVN001-CVN002-CVN003-CVN004-CVN007-CVN014-CVN015. Numbers at branches in the right tree show the MLST STs. The figure represents the association of MLVA pattern and ST for each HUSEC isolate. HUSEC strains and corresponding STs (14) are connected by lines. OR, O rough; H−, nonmotile; nt, not typeable with known O and/or H antisera.

Analysis of concordance between MLVA profiles and STs resulted in adjusted Rand and Wallace coefficient values of 0.155 and 0.143, respectively, indicating low predictability of MLST results based on MLVA results and vice versa. Trees determined by the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA) on the basis of either MLVA or MLST profiles are displayed in Fig. 1, portraying correlations between MLVA and MLST profiles. Both coefficient values and the phylogenetic trees underlined the limited concordance between MLVA and MLST. As examples of high concordance, two isolates, HUSEC011 and HUSEC012 (both members of serogroup O111), shared the same ST (ST16) and differed in only one VNTR locus (CVN014). Moreover, five isolates of serogroup O26 (HUSEC013, -014, -017, -018, and -020) were single-locus variants in the MLVA scheme, and all belonged to clonal complex 29 (14). Interestingly, this concordance was only partially present in serogroup O157. Whereas the two sorbitol-fermenting (SF) isolates of serotype O157:H− (HUSEC004 and -006, with ST11 and -587) differed in only one locus (CVN003), the non-SF isolate belonging to serotype O157:H7 (HUSEC003) shared ST11 but exhibited a different MLVA pattern with only two identical MLVA loci (CVN001 and CVN007) (Fig. 1). This resulted in a tree branch distinct from those of the SF serotype O157 isolates. These results indicate that MLVA is suitable for short-range epidemiology studies through the differentiation of closely related strains, such as the SF O157:H− isolates (8), but is not able to properly deduce long-term evolutionary events, such as the stepwise emergence (3, 10) that proceeded from O55:H7 to O157:H7/H− (Fig. 1).

In summary, evaluation of this pan-E. coli MLVA scheme by investigations using the HUSEC collection demonstrates its great ability to discriminate among different serogroups. Lindstedt et al. even used this scheme to differentiate serotype O157 from other E. coli pathovars and Shigella spp. (11). Deeper analysis of serogroup O26, as shown by Miko et al. (15), demonstrated the ability of this pan-E. coli MLVA scheme to further differentiate strains within serogroup O26 and to provide a serogroup and/or serotype prediction. However, to evaluate its discriminatory power in comparison to PFGE for other non-O157 serogroups, further studies are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (0315219A) and by the Medical Faculty of the University Münster (9817044).

We thank Shana Leopold (Inst. Hygiene, University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany) for critical reading of the manuscript.

D. Harmsen has declared a potential conflict of interest. He is one of the developers of the Ridom EpiCompare software mentioned in the manuscript, which was a development of the company Ridom GmbH that is partially owned by him. All other authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 August 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carriço J. A., et al. 2006. Illustration of a common framework for relating multiple typing methods by application to macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2524–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feil E. J. 2004. Small change: keeping pace with microevolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feng P. C. H., et al. 2007. Genetic diversity among clonal lineages within Escherichia coli O157:H7 stepwise evolutionary model. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:1701–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frothingham R. 1995. Differentiation of strains in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by DNA sequence polymorphisms, including rapid identification of M. bovis BCG. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:840–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helgason E., Tourasse N. J., Meisal R., Caugant D. A., Kolsto A. 2004. Multilocus sequence typing scheme for bacteria of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:191–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hunter P. R., Gaston M. A. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465–2466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hyytiä-Trees E., Smole S. C., Fields P. A., Swaminathan B., Ribot E. M. 2006. Second generation subtyping: a proposed PulseNet protocol for multiple-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 (STEC O157). Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:118–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jenke C., et al. 2010. Phylogenetic analysis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157, Germany, 1987–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:610–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karch H., Tarr P. I., Bielaszewska M. 2005. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leopold S. R., et al. 2009. A precise reconstruction of the emergence and constrained radiations of Escherichia coli O157 portrayed by backbone concatenomic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8713–8718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lindstedt B., Brandal L. T., Aas L., Vardund T., Kapperud G. 2007. Study of polymorphic variable-number of tandem repeats loci in the ECOR collection and in a set of pathogenic Escherichia coli and Shigella isolates for use in a genotyping assay. J. Microbiol. Methods 69:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindstedt B., Heir E., Gjernes E., Vardund T., Kapperud G. 2003. DNA fingerprinting of Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli O157 based on multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeats analysis (MLVA). Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maiden M. C., et al. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3140–3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mellmann A., et al. 2008. Analysis of collection of hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1287–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miko A., Lindstedt B., Brandal L. T., Lobersli I., Beutin L. 2010. Evaluation of multiple-locus variable number of tandem-repeats analysis (MLVA) as a method for identification of clonal groups among enteropathogenic, enterohaemorrhagic and avirulent Escherichia coli O26 strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 303:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murchan S., et al. 2003. Harmonization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for epidemiological typing of strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a single approach developed by consensus in 10 European laboratories and its application for tracing the spread of related strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noller A. C., McEllistrem M. C., Pacheco A. G. F., Boxrud D. J., Harrison L. H. 2003. Multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis distinguishes outbreak and sporadic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5389–5397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prager R., Strutz U., Fruth A., Tschäpe H. 2003. Subtyping of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains using flagellar (H)-antigens: serotyping versus fliC polymorphisms. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Supply P., et al. 2003. Linkage disequilibrium between minisatellite loci supports clonal evolution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a high tuberculosis incidence area. Mol. Microbiol. 47:529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swaminathan B., Barrett T. J., Hunter S. B., Tauxe R. V. 2001. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:382–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Belkum A., Scherer S., van Alphen L., Verbrugh H. 1998. Short-sequence DNA repeats in prokaryotic genomes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:275–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]