Abstract

Detachment of epithelial cells from matrix or attachment to an inappropriate matrix engages an apoptotic response known as anoikis, which prevents metastasis. Cellular sensitivity to anoikis is compromised during the oncogenic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), through unknown mechanisms. We report here a pathway through which EMT confers anoikis resistance. NRAGE (neurotrophin receptor-interacting melanoma antigen) interacted with a component of the E-cadherin complex, ankyrin-G, maintaining NRAGE in the cytoplasm. Oncogenic EMT downregulated ankyrin-G, enhancing the nuclear localization of NRAGE. The oncogenic transcriptional repressor protein TBX2 interacted with NRAGE, repressing the tumor suppressor gene p14ARF. P14ARF sensitized cells to anoikis; conversely, the TBX2/NRAGE complex protected cells against anoikis by downregulating this gene. This represents a novel pathway for the regulation of anoikis by EMT and E-cadherin.

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic tumor cells survive detachment from their extracellular matrix of origin and/or attachment to inappropriate matrices for extended periods of time, conditions that engage an apoptotic response known as anoikis in normal cells. Tumor cell resistance to anoikis is driven by (epi)genetic alterations or aberrant signaling responses that occur uniquely in the tumor microenvironment, leading to constitutive activation of integrin/growth factor signaling and inactivation of the core apoptotic machinery (23, 27, 28, 30–32, 76, 87).

The oncogenic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is thought to play an important role in tumor progression (46, 88, 91). The focus of the present study was to understand the molecular basis of the tight correlation between anoikis resistance and the oncogenic EMT (31, 51, 54, 68, 89). A common hallmark of EMT is the breakdown of E-cadherin expression or function (103), which suffices to circumvent anoikis in some contexts. For example, the targeted knockout of the E-cadherin gene in a mouse mammary tumor model or the stable knockdown of E-cadherin in a mammary epithelial cell line confers anoikis resistance (19, 68). This implies that EMT-promoting transcription factors such as ZEB1/2, Snail1/2 and Twist can abrogate anoikis both by directly regulating apoptosis control genes and by suppressing E-cadherin expression, the latter triggering signaling events—to be addressed here—that control other apoptosis regulatory genes (46, 53, 75, 85, 89, 92).

Ankyrin-G plays a critical role in linking the actin cytoskeleton to the cell membrane and in the biogenesis of the lateral membrane domain of epithelial cells. The N-terminal ankyrin repeat domain interacts with E-cadherin, linking the latter to the cytoskeleton via interaction with spectrin complexes. Accordingly, ankyrin-G localizes primarily to adherens junctions (50, 65, 73). In addition, ankyrin-G contains two domains, a death domain and a ZU-5 domain, whose homologues in other proteins regulate apoptosis (99, 101). The downregulation of the ankyrin-G gene (ank3) correlates with poor prognosis in diverse human tumors (34), suggesting that ankyrin-G might mediate anoikis regulatory signals downstream of E-cadherin.

The melanoma antigen (MAGE) family is comprised of two subfamilies, type I, which are expressed only in embryonic tissue and melanomas, and type II, expressed almost ubiquitously in adult tissues. The type I members are highly expressed in melanomas and are being developed as potential tumor antigens for cancer vaccines. All members (>50) share a highly conserved ∼190-amino-acid MAGE homology domain (2, 15). MAGE-D1/NRAGE is a type II protein that interacts with p75 neurotrophin receptor and the netrin receptor Unc5 to mediate apoptosis (82), as well as with various transcription factors, indicating multiple functions that depend upon its localization within the cell (2, 83). Consistent with its proapoptotic function, NRAGE knockout mice show a developmental defect in neuronal apoptosis in the brain (5). Nevertheless, other evidence suggests a protumorigenic role of NRAGE. NRAGE is overexpressed in cancer of the lung, kidney, and head or neck (6, 7, 33) and promotes survival of PC12 pheochromocytoma cells (77). The related protein MAGE-A3 supports melanoma cell survival and is overexpressed in lung cancer, correlating with poor prognosis (36, 102). The NRAGE orthologue trophinin/MAGE-D3 is overexpressed in colorectal carcinoma, where it promotes tumor metastasis (38). Thus, although NRAGE is proapoptotic with respect to the p75 and Unc5 receptors, paradoxical protumorigenic functions of the protein have not yet been explored.

TBX2 and TBX3, members of the T-box family of transcriptional repressor proteins, are critical regulators of mesoderm specification, mammary gland development, cell cycle, senescence, stem cell self-renewal and apoptosis (44, 45, 81, 93, 100). TBX2, an oncogene that is overexpressed in most melanomas as well as a subset of breast and pancreatic tumors (59, 81, 93), collaborates with c-myc, Ras, Bmi-1, retinoblastoma protein loss, and LPA receptors to transform cells by conferring anchorage-independent growth, overcoming Ras-induced cell senescence, and counteracting c-myc-induced apoptosis (42, 45, 96); it can also enhance tumor chemoresistance (17). TBX2 directly represses p14ARF gene, one of the most frequently downregulated tumor suppressor genes in human cancer (47). P14ARF promotes apoptosis through p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms (86). The potential roles of TBX2 or p14ARF in anoikis have not been addressed.

We demonstrate here that NRAGE and TBX2 interact, repress the transcription of p14ARF, and suppress anoikis. P14ARF is shown to be critical for anoikis sensitivity. Ankyrin-G is shown to sequester NRAGE in the cytoplasm, inhibiting its collaboration with TBX2 in normal cells, permitting p14ARF transcription and anoikis sensitivity. During oncogenic EMT, ankyrin-G is shown to be downregulated, promoting NRAGE-TBX2 repressor activity, downregulating p14ARF, and conferring anoikis resistance. We discuss here a novel transcriptional pathway through ankyrin-G that is regulated positively by EMT and negatively by E-cadherin, programming relative resistance or sensitivity to anoikis, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

HMLE, HMLE+shEcad, HMLE+Twist-ER, HMLER, HMLER+shEcad, and HMLER+Twist cells were generously provided by R. Weinberg (Whitehead/Massachusetts Institute of Technology). The HMLE series was maintained in one part HMLE medium (Dulbecco modified Eagle medium/F-12 plus 5% horse serum, 1× penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine [PSG], 10 μg of insulin/ml, 10 ng of epidermal growth factor/ml, and 0.5 μg of hydrocortisone/ml) to one part MEGM (Lonza). The HMLE-Twist-ER cells (HMLE+Twist) were grown in the presence of 20 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen. The HMLER series were maintained in MEGM. MCF10a cells (Karmanos Cancer Center) were maintained in HMLE medium with 0.1 μg of cholera toxin/ml. HT1080, SW13, NCI-H1299 and MDA-MB-435 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum plus 1× PSG or in RPMI 1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum plus PSG (NCI-H1299).

Derivative cell lines were generated by retrovirus or lentivirus infection using the vectors described under DNA constructs. Retroviruses were packaged using 293+GP2 cells (Clontech) cotransfecting with pAmpho or pEco; lentiviruses were packaged using 293T cells, cotransfecting 10 μg of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vector plus 6.7 μg of sPAX2 plus 3.3 μg of CMV-VSV-G (A. Ivanov). Viral supernatants were precleared by filtration through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters, added to target cells in the presence of 4 μg of Polybrene/ml, and incubated for 6 h. After infection, cells were selected either in puromycin (2 μg/ml) or zeocin (300 μg/ml) or flow sorted twice for green fluorescent protein (GFP) or red fluorescent protein (RFP) expression. Expression of the transgenes was verified by Western blotting and immunofluorescence. Where required, 1 μg of doxycycline/ml was added to growth media to induce shRNA expression in cells with pTRIPZ-based shRNAs or 0.2 μg of doxycycline/ml was used for the inducible p14ARF expression construct.

P19ARF-knockout and wild-type mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs), kindly provided by N. Sharpless (University of North Carolina), and NRAGE-knockout and wild-type MEFs, kindly provided by P. Barker (McGill University), were immortalized with simian virus 40 (SV40) T-antigen by infection with the ZipTer retrovirus (provided by P. Soriano, Hutchinson Cancer Center).

Yeast two-hybrid screening.

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed by Hybrigenics, S.A., Paris, France. The coding sequence for the full-length MAGED1 protein (GenBank accession no. gi 52632376) was PCR amplified and cloned into pB27 as a C-terminal fusion to LexA (N-LexA-MAGED1-C). The construct was checked by sequencing the entire insert and used as a bait to screen a random-primed human breast tumor epithelial cell cDNA library constructed in pP6. pB27 and pP6 derive from the original pBTM116 (95) and pGADGH plasmids (4), respectively. A total of 63 million clones (6.3-fold the complexity of the library) were screened using a mating approach with Y187 (MATa) and L40DGal4 (MATa) yeast strains as previously described (29). Next, 324 His+ colonies were selected on a medium lacking tryptophan, leucine, and histidine and supplemented with 0.5 mM 3-aminotriazole to handle bait autoactivation. The prey fragments of the positive clones were amplified by PCR and sequenced at their 5′ and 3′ junctions. The resulting sequences were used to identify the corresponding interacting proteins in the GenBank database (National Center for Biotechnology Information) using a fully automated procedure. A confidence score (the predicted biological score) was attributed to each interaction, as previously described (26).

Automated quantitative analysis (AQUA). (i) Cohorts.

For the multitumor type analysis an array (Yale Tissue Microarray 96) containing 19 types of tumor was used. For each tumor type, there were 20 tumor tissue samples and 10 corresponding normal tissue samples, for a total of 360 samples of tumor tissue and 180 samples of normal tissue. An additional cohort (Yale Tissue Microarray 118), with 25 colorectal cancer samples and 10 normal colon samples, was used for the study of NRAGE in colon cancer. For studies of NRAGE expression in melanoma, tissue microarrays (Yale Tissue Microarrays 98 and 66) containing a combined 30 metastases, 30 nevi, and 30 primary tumor samples were used.

(ii) Immunohistochemistry.

For detection of the NRAGE protein, paraffin-fixed formalin-embedded tissue microarrays containing tumor samples of interest were deparaffinized using xylene. The slides then underwent antigen retrieval and rehydration through pressure cooking in a pH 6 citrate buffer. Prior to antigen application, the slides were incubated in a 0.3% bovine serum albumin and 0.5% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline solution (BSA/Tween) for 30 min at room temperature. A 1:100 dilution of NRAGE (monoclonal antibody [MAb] clone 48; Becton Dickinson) to BSA/Tween with a 1:100 concentration of polyclonal rabbit anti-bovine cytokeratin antibody (Z0622; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) was then applied overnight at 4°C. Next, the slides were incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated goat anti-rabbit reagent (A11010; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted 1:100 in EnVision horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-mouse polymer (K4001, lot 10026680; Dako). To detect the target fluorescently, tyramide-conjugated cyanine 5 (FP1117; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) was applied at a 1:50 dilution. Nuclei were detected with mounting medium (ProLong Gold, P36931; Molecular Probes) containing DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

(iii) Analysis.

Protein expression was quantified by using AQUA (8) software that enables imaging and precise measurement of protein concentration in subcellular compartments. AQUA (HistoRx, New Haven, CT) allows the exact measurement of protein concentration within subcellular compartments, as described in detail elsewhere (8). In brief, a series of high-resolution monochromatic images were captured by the PM-2000 microscope (HistoRx). For each histospot, in- and out-of-focus images were obtained using the signal from the DAPI, cytokeratin-Alexa Fluor 546, and target protein (NRAGE)-cyanine 5 (Cy5) channels. The target protein was measured using a channel with emission maxima above 620 nm, in order to minimize tissue autofluorescence. Epithelial tumors were distinguished from stromal and nonstromal elements by creating an epithelial tumor “mask” from the cytokeratin signal, melanomas were identified by the S100 protein signal. This created a binary mask (with each pixel being either “on” or “off”) on the basis of an intensity threshold set by visual inspection of histospots. The AQUA score of the target protein in each subcellular compartment was calculated by dividing the target compartment pixel intensities by the area of the compartment within they were measured. AQUA scores were normalized to the exposure time and bit depth at which the images were captured, allowing scores collected at different exposure times to be directly comparable. Specimens with less than 5% tumor area per spot were excluded.

siRNA/shRNA methods.

The small interfering RNA (siRNAs) used here are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

siRNAs used in this study

| siRNA | Target | Sequence(s) (5′–3′) | Source (catalog no.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NR-D3 | NRAGE | CUACUAAAGUGGGCCCAAA | Dharmacon (J-006682-07) |

| NR-D4 | NRAGE | GAGCAAAUAAGUUGGUCAA | Dharmacon (J-006682-06) |

| NR-S2 | NRAGE | UGAGUGAGAUGUUGGAUAU(dT)(dT) | Sigma (custom) |

| Smartpool | NRAGE | CUACUAAAGUGGGCCCAAA, GAGCAAAUAAGUUGGUCAA, GUGAAUACACUGAUGUUUA, GGACCCGCAAGAUUAAUAA | Dharmacon (L-006682-0005) |

| Ank-D1 | Ank3 | UAACUUCGGUCUUGACAAA | Dharmacon (J-011207-06) |

| Ank-D2 | Ank3 | AAGCGUAUCUGCAGGAUUA | Dharmacon (J-011207-05) |

| Ank-D3 | Ank3 | UCUCAGAGCUUCAUGUUAU | Dharmacon (J-011207-08) |

| Ank-D4 | Ank3 | CGUCUUCUCUGUAGCAUUA | Dharmacon (J-011207-07) |

| ARF-S1 | P14ARF | GCGAGAACAUGGUGCGCAGUU | Sigma (custom) |

| TBX2-DSP | TBX2 | AAGCGUAUCUGCAGGAUUA, UAACUUCGGUCUUGACAAA, CGUCUUCUCUGUAGCAUUA, UCUCAGAGCUUCAUGUUAU | Dharmacon (L-011207-00-0005) |

| TBX2-Ori | TBX2 | AGAUCACGACAAGAUCUAACCAGdTdC, ACAGCACAGAAUGAGUAUUUAUUdTdA, CGCAUGUACAUCCACCCAGACAGdCdC | Origene (SR304727) |

shRNA construct.

The shRNA construct used in the present study was NRAGE/MAGED1 in pTRIPZ (Open Biosystems, catalog no. RHS4430-98843439 [TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAGCCCAAATGCCACCTACAATTTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAAATTGTAGGTGGCATTTGGGCCTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA]).

RT-PCR.

The following primer pairs were used in the present study for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR): for Ank3, Ank3F (AGAGACTGGAGTTCCTGGAAGGAG) and Ank3R (TGGAGAGCGTTCAACCCATTCTGA) (this primer pair spans the 5′ untranslated region [5′UTR] and the N-terminal coding sequence of an ∼210-kDa ankyrin transcript [accession number BX537917.1]; it is absent from the “short-ankyrin-isoform” transcripts p105 and p120, e.g., uc001.jkw.1 in the UCSC Bioinformatics Database); for P14ARF, 5-p14arf (AGCCGCTTCCTAGAAGACCA) and 3-p14arf (TCAATCGGGGATGTCTGAG) (these primers are specific for exon 1β); and for GAPDH, 5-GAPDH (GTCGGAGTCAACGGATTT) and 3-GAPDH (CCACGATACCAAAGTTGTCA).

NRAGE/TaqMan.

For NRAGE/TaqMan analyses, TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), MAGED1 assay primers (Hs00986269_m1), and actin control primers were used.

The cancer cDNA panels for breast cancer (BCRT102) and lung cancer (HLRT103) were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD) and probed using TaqMan gene expression master mix, MAGED1 assay primers, and β-actin control primers under the default conditions recommended by ABI on an ABI 7500 instrument. Expression values shown in the Fig. were calculated as 2−ΔCT, where ΔCT is the difference between the threshold cycle (CT) values for actin minus MAGED1.

For cell line RT-PCRs, RNA was purified from cell lines by using an RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and cDNA was synthesized using the Invitrogen 18080-051 Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR with 5 to 10 μg of RNA template with oligo(dT) primers and then amplified with Taq polymerase.

siRNA transfection and anoikis assays.

For subconfluent cells assayed by DNA fragmentation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), 5 × 104 cells were plated in the wells of six-well collagen-coated dishes. Two duplicate wells with target siRNA and two duplicate wells with control siRNA, using 500 μl of Opti-MEM containing 5 μl of 20 μM siRNA and 5 μl of Lipofectamine RNAi-Max, were added to a well containing 2.0 ml of Opti-MEM. After 4 to 6 h the cells were refed with regular growth medium and, 24 h later, each well was split into one 60-mm dish. These were further incubated 48 h, treated with trypsin, and resuspended in 1.5 ml of growth medium per time point containing 100,000 cells that was plated in a 35-mm Ultralow attachment well for specified periods of time in the presence of 0.5% methylcellulose. Alternatively, cells containing doxycycline-inducible shRNA or ARF constructs were induced with 0.2 μg (ARF) or 1.0 μg (shRNA) of doxycycline/ml for 48 h prior to detaching the cells. At each time point, including time zero, the cells were spun down at 8,000 rpm for 15 s in a microfuge tube, washed in ice-cold Dulbecco-modified phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS), and lysed in 100 μl of Roche cell death ELISA lysis/incubation buffer that was supplemented with 0.5% Triton X-100 or with 0.5% Triton X-100–10 mM EDTA–PBS. (Note that, without supplementation, this buffer did not lyse aggregated cells efficiently.) Lysates were cleared at 13,200 rpm for 10 min, and 5 to 15 μl was assayed in a total of 100 μl of Roche cell death ELISA lysis/incubation buffer in the Roche system and read in a Perkin-Elmer envision/excite plate-reading spectrophotometer. Time zero values, which were generally unaffected by the siRNAs we transfected in the present study, were subtracted from the final values shown in the figures.

Trypan blue exclusion assays for anoikis were performed by suspending 100,000 cells in 1.5 ml of growth medium for 8 h, collecting the cells, resuspending them in 1.0 ml of Accumax (Innovative Cell Technologies), and incubating them for 10 min at room temperature to generate single cell suspensions. This was followed by the addition of an equal volume of trypan blue staining solution (Sigma) and quantitation of both trypan blue-negative and total cell numbers using a Countess cell counter (Invitrogen). The values displayed are trypan blue-positive cells with the time zero values subtracted.

Caspase activation assays for anoikis were performed by assaying Triton X-100 buffer cell extracts for cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate Ac-DEVD-AFC, and the Vmax values were calculated by using a Molecular Dynamics fluorescent plate reader, as described previously (37).

Protein interaction methods. (i) Endogenous co-IP.

For the coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) of NRAGE with TBX2, HMLE+shEcad cells (two confluent 100-mm dishes) were washed and lysed in IP buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Pierce]). Lysates (∼400 μg) were precleared at 13,200 rpm for 10 min and then preabsorbed for 30 min with 80 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) that had been preequilibrated in IP buffer with 10 mg of BSA and 10 mg of ovalbumin/ml. After clearing, 4 μg of NRAGE polyclonal antibody (pAb; Santa Cruz catalog no. sc-28243) or normal IgG (Covance) was added, and the samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with rotation. Protein A-Sepharose (40 μl) was then added, and incubation was continued for an additional hour. After three washes with standard IP buffer, the samples were boiled in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and analyzed by Western blotting as described below.

For NRAGE/ankyrin-G coimmunoprecipitation, cell lysates (∼400 μg) were immunoprecipitated with an ankyrin-G pAb that was custom generated by Open Biosystems against a glutathione S–transferase (GST)–ankyrin protein (amino acids 5209 to 5664) that we produced in the vector pGEX-4T3 in Escherichia coli BL21. The specificity of this antibody appeared to be acceptable on a Western blot and was subsequently verified by siRNA knockdown and coimmunoprecipitation data.

(ii) Cotransfection/pulldown methods.

293T cells were plated in 35-mm collagen-coated wells and cotransfected, using 150 μl of cells (in 2.0 ml of Opti-MEM) per well of a solution containing 200 μl of Opti-MEM, 1 μg of each expression construct (2 μg of total DNA), and 6 μl of Fugene-HD (Roche). After 4 h, cells were returned to normal growth medium (DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine). After 28 to 36 h, the cells were collected by pipetting each well in 1.0 ml of cold PBS, pelleted in a microfuge at 8,000 rpm for 15 s, and lysed in standard IP buffer (600 μl), followed by preclearing the lysates at 13,200 rpm for 10 min. Lysates were precipitated with 40 μl of a 50% slurry of glutathione-Sepharose (GE/Amersham) or FLAG-agarose (Sigma) that had been preequilibrated with IP buffer containing 10 mg of BSA/ml and washed. After 2 h of incubation at 4°C with rotation, precipitates with washed three times with IP buffer. FLAG beads were eluted by incubation in 50 μl of 0.1 M glycine (pH 2.8) at 4°C for 10 min; after removal of the beads by spinning, 40 μl of the supernatant was neutralized by the addition of 8.8 μl of 0.5 M Tris (pH 7.5), which was then diluted with 2× SDS sample buffer for gel analysis. GST beads were simply washed three times and boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer.

(iii) Western blotting.

Western blots utilized Novex/Invitrogen 4 to 12% gradient gels and were transferred under standard conditions in Tris-glycine–20% methanol buffer (120 V, 90 min), except for the ankyrin detection, where transfer buffer contained 5% methanol and transfer was overnight at 40 V. The secondary antibodies anti-mouse antibody–HRP and anti-rabbit antibody–HRP were from Bio-Rad. For detecting ankyrin-G and TBX2 in coimmunoprecipitation experiments, Clean-Blot secondary antibody (Pierce/Thermo) was used to avoid the detection of precipitated IgG on the blot. Blots were developed by using either enzyme-linked chemiluminescence (ECL West Pico; Pierce) or, for the more quantitative applications, by using fluorescently tagged secondary antibodies, buffers, and a scanning instrument from LiCor. The quantitation generated by the software is based on raw pixel integrations. Antibodies used for Western blotting were obtained from the indicated sources: NRAGE, a BD MAb clone 48 (during the course of this project, this antibody was discontinued by the company but was custom produced at our request); ankyrin-G, a custom pAb (see above) or the H315 pAb from Santa Cruz (the results obtained with this antibody were highly lot specific); p14ARF, Bethyl Laboratories pAb A300-340A; FLAG, Sigma MAb M2; HA, Covance HA.11 MAb (ascites); TBX2, Santa Cruz pAb sc-48780; α-tubulin, Millipore MAb DM1A; β-actin, Cell Signaling MAb clone 8H10D10; CD44, Santa Cruz MAb SC9660; E-cadherin, BD Biosciences MAb clone 36; PARP, Millipore MAb C-2-10; and GADPH, Sigma-Aldrich pAb G9545.

Expression constructs. (i) Ankryin-G.

All sequences were subcloned from clone DKFZ p686P17114 (Imagenes, Germany), which contains accession number BX537917, since this was the major ankyrin-G isoform expressed in our cell lines. For mapping of ankyrin fragments interacting with NRAGE, fragments were amplified by PCR as BamHI-HpaI fragments and subcloned into the BglII-HpaI site of the p3×HA vector, a derivative of pRC/CMV2 constructed by Deborah Anderson (University of Saskatchewan). 3×HA-ankyrin-p105 was used for the cotransfection/pulldown experiment to map the domain on NRAGE that interacts with ankyrin-G. FLAG-expressing constructs were generated by using the vector 3×FLAG-CMV10 (Sigma). AnkryinΔMBD-CAAX was constructed by three-way ligation of a fragment containing the second ZU5 domain through the C terminus of ankyrin-G (dZUA,Ct-Cx-f, TTATTAAGATCTGTCCCGGATTAAGCAGGAAAG; dZUA,Ct-CX-r, TTATTAGTCGACACCATCAACAGGGTCATG), together with a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the CAAX sequence from K-ras (CAAX-F, TCGACAGCAAGGACGGCAAGAAGAAGAAGAAGAAGAGCAAGACCAAGTGCGTGATCATGTAGG; CAAX-r, GATCCCTACATGATCACGCACTTGGTCTTGCTCTTCTTCTTCTTCTTCTTGCCGTCCTTGCTG) into p3×FLAG-CMV10. After sequence confirmation, the complete coding sequence was subcloned into the XhoI site of MSCV-IRES-zeo (Addgene) by PCR amplification.

(ii) NRAGE.

All sequences were subcloned by PCR from the Origene NRAGE MAGE-D1 transcript variant 2 (778 amino acids, accession no. NM_006986), since this was the major NRAGE isoform expressed in our cell lines. To generate NRAGE and NRAGE-NLS retroviral constructs, NRAGE was PCR amplified with a forward primer that included a hemagglutinin (HA) tag sequence and a XhoI site and was subcloned into the XhoI-NotI site of MSCV-IRES-Puro. To construct NRAGE-NLS, the complete NRAGE coding sequence upstream of the stop codon was amplified with the forward primer described above and with a reverse primer containing an NheI site. Separately, the triple nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence from the vector pEYFP-NLS (Promega) was PCR amplified to produce an NheI-NotI fragment. The NRAGE and NLS fragments were three-way ligated into the MSCV-IRES-Puro vector. Subsequently, the complete coding sequence was subcloned into the pMIG retroviral vector (Addgene), permitting GFP selection by flow cytometry. HA-NRAGE was generated in nonretroviral expression vectors pcDNA3.1 by PCR with the inclusion of a single HA tag on the forward primer or in p3×HA. 3×FLAG-NRAGE was generated using p3×FLAG-CMV10. 3×HA-NRAGE (wild type) and 3×HA-NRAGE (ΔC) were also subcloned into the vector MSCV-IRES-Puro (Addgene) for expression in the NRAGE-KO MEFs. For GST-NRAGE constructs expressed in 293T cells, PCR amplification was used to subclone the indicated sequences into the GST fusion mammalian cell expression vector pEBG2 (61).

(iii) Mouse E-cadherin.

Mouse E-cadherin was obtained as a pWZL-blast retroviral construct from Addgene.

(iv) TBX2.

All TBX2 constructs were derived from a mouse TBX2-3×FLAG expression construct generously provided by Colin Goding (Oxford University, United Kingdom). TBX2-ΔRD was constructed in p3×FLAG by amplification with the primers TBX2-delC-f (TTATTTCTAGAAATGAGAGAGCCGGCGCTG) and TBX2-delC-r (TATATGGATCCGGCGCCTCCGCTACTGCC). To subclone TBX2-3×FLAG into the pMIG retroviral vector, a BglII (partial)-SspI fragment from C. Goding's construct was subcloned into the BamHI-HpaI site of pMIG.

(iv) P14ARF.

6×HA-ARF in pLUT, a doxycycline-inducible vector based on pTRIPZ, was provided by Alexey Ivanov (West Virginia University).

Mammosphere assays.

A total of 10,000 cells were plated per 35-mm ultra-low-cluster plate in HMLE medium plus 0.5% methylcellulose and refed every third day by adding 1 ml of medium. The total numbers of mammospheres greater than ∼75 μm in diameter were counted after 12 days in culture. The averages of triplicate wells are shown in the figures.

Soft agar colony assays.

A total of 150,000 MDA-MB-435 cells were plated on six-well dishes. The cells were transfected with siRNAs for luciferase (control) or NRAGE (Dharmacon Smartpool). After 24 h, the cells were replated on 60-mm dishes. The next day, the cells were suspended with growth medium, and 5,000 cells were added to the 14-ml snap-cap tube containing 0.5 ml of 0.35% soft agar solution (prepared in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum plus 1× PSG) and then transferred into the wells of a low-attachment 24-well dish. After the samples were allowed to gel at room temperature for 30 min, the plates were incubated in a 37°C tissue culture incubator within a humidified glass tray. Every 3 to 4 days during growth, the cells were refed with 0.5 ml of DME complete growth medium. For the MB435 derivatives, the colonies were counted after 10 days; eight wells were averaged to generate the results shown in the figures (5,000 cells plated per well × 8 wells, counted >3,000-μm2 colonies). For the HMLE-based assay, two samples, each of which contained six fields, were averaged together to generate the data in the figures.

Immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence analysis for E-cadherin (BD MAb clone 36) and ankyrin-G (Santa Cruz pAb H215) was performed with methanol-fixed cells; other antigens were detected by using cells fixed on collagen-coated coverslips with 2% formaldehyde (in D-PBS or Hanks balanced salt solution) for 20 min and quenched in 100 mM glycine for 10 min. Where indicated in the text, the cells were pretreated with 5 ng of leptomycin B/ml for 30 min prior to fixation. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 4°C, the samples were processed using background-reducing methods described previously (18), which included goat serum and goat anti-mouse Fab fragments in the blocking and antibody dilution buffers. The secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor-labeled goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen. The HA, FLAG, and NRAGE MAbs were the same ones used for Western blotting (see above). Image intensities were analyzed using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health [NIH]). The standard deviations in these experiments refer to the averaging of multiple fields, randomly assigned groups of fields, or duplicate slides.

ChIP.

For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of NRAGE on the ARF promoter, 293T cells (100-mm dishes; Turbofect Reagent [Fermentas]) were cotransfected with a construct containing the upstream 330 bp of the ARF promoter that was constructed in pGL3-Basic (Promega) by PCR amplification of a template that was provided by K. Robertson (Medical College of Georgia) using the primers ARFprom-f (TATTAACTCGAGtggagttgcgttccaggcgt) and ARFprom-r (TATATAAAGCTTGAGCTCGGCAGCCGCTGCGC). The transfections utilized 3 μg of the wild-type promoter construct or the mutant promoter (constructed by mutagenization with GGGGGCAGGAGTGGCGCTGCTTGACTCTAAGTCCAAAGGGCGGCGCAGC and GCTGCGCCGCCCTTTGGACTTAGAGTCAAGCAGCGCCACTCCTGCCCCC, using a Stratagene QuikChange kit, followed by sequencing), 3 μg of 3×FLAG-NRAGE (constructed as described above or 3×FLAG empty vector), and 2 μg of TBX2 (Origene catalog no. SC125962) or empty vector (pCMV6XL5, constructed by digesting the TBX2 clone with NotI and religation). After 24 h, the cells in 5.0 ml of growth medium were fixed with 0.33 ml of 16% formaldehyde for 15 min (37°C), quenched with 0.33 ml of 2.5 M glycine for 5 min, and scraped into ice-cold PBS containing 1× Pierce HALT protease inhibitor mix. The cell pellets were then resuspended in 0.6 ml of mIP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM EDTA, 1× Pierce protease inhibitors) and sonicated on ice in a Diagenode Bioruptor for 30 min with a 30-s on/30-s off program. After clearing at 13,200 rpm for 12 min, the samples were precipitated overnight with 40 μl of a 50% slurry of FLAG-agarose (Sigma) that had been preequilibrated in FA buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.5],140 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1× Pierce protease inhibitors) containing 200 μg of salmon sperm DNA (Millipore)/ml. Precipitates were washed twice with FA buffer, once with FA buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, twice with LiCl solution (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.25 M LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM EDTA), and once with Tris-EDTA (TE). Precipitates were then boiled for 15 min in 0.1× TE and cleared, and 1- to 10-μl portions were assayed by PCR using 2× Taq master mix (Phenix Biosciences) and a program of 94°C for 1 min (1 cycle), followed by 25 to 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, prior to analysis on a 1.2% agarose gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. For ChIP analysis of the Gal4-TK promoter, analogous protocols were used, but we substituted Gal4-TBX2 or Gal4-TBX2-RD (amino acids 515 to 574 of mouse TBX2 [J. Reecy, Iowa State University]), both in pBind, and 3×Gal4-tk-luc in pGL3-promoter (Q. Zhang, Oregon Health Sciences University). The PCR primers were as follows: for Gal4-tk, G4-CHIP-f2 (AAAATAGGCTGTCCCCAGTG) and G4-CHIP-r1 (CCTCGGCCTCTGCATAAATA), and for ARF, ARF-Chn-f1 (CTCAGAGCCGTTCCGAGATC) and ARF-Chn-r1 (AACAGTACCGGAATGCCAAG).

For the endogenous CHIP assays, cell lines expressing 3×FLAG-NRAGE (in MSCV-IRES-Puro vector) were generated, and similar expression levels between cell lines that were ∼3-fold above endogenous NRAGE were obtained. This enabled the ChIP using the FLAG antibody, which was not feasible with NRAGE antibodies. The protocol from Richard Myers' lab (Hudson-Alpha Institute, Huntsville, AL [see http://hudsonalpha.org/myers-lab/protocols]) was followed with the following modifications. (i) FLAG-agarose beads (EZ view, Sigma) were used instead of magnetic beads; these were blocked with BSA and salmon sperm DNA prior to use. (ii) We reduced the sodium deoxycholate in the LiCl wash buffer and radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer to 0.25%, and the SDS in the RIPA buffer to 0.05%. (iii) We used 16% EM-grade (para)formaldehyde from EM Sciences/Fisher for cross-linking. PCRs were performed using Promega 2× Taq master mix, with the primers Endo-f1 (TGGGTCCCAGTCTGCAGTTA) and Endo-r1 (GGATGTGAACCACGAAAACC).

Reporter assays.

Two days prior to plasmid transfections, 40,000 HMLE+shEcad or 293T cells were transfected with NRAGE siRNA (Dharmacon Smartpool) or Dharmacon nontargeting siRNA1. The cells were resplit onto collagen-coated wells the following day. After 24 h, a Gal4-tk-luciferase construct was cotransfected with Gal4-TBX2-RD (J. Reecy) and TK-lacZ (A. Ivanov) by using Lipofectamine LTX reagent (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 1 μg to DNA to 2 μl of Plus reagent to 3 μl (2.5 μg of DNA total). For the 293T cells, cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant ARF promoters (see ChIP discussion), together with various amounts of the TBX2 expression plasmid in pCMV6XL5 (Origene). The following day, the cells were lysed in 1× cell culture lysis buffer and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity in 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent or 150 μl of 1× β-galactosidase assay buffer (all Promega), which were analyzed in a Tecan luminometer or a Perkin-Elmer Envision/Excite apparatus, respectively. All luciferase values, based on duplicate assays, were normalized against β-galactosidase.

RESULTS

EMT suppresses anoikis and ankyrin-G expression, and ankyrin-G promotes anoikis.

Oncogenic EMT has been induced by the knockdown of E-cadherin (“shEcad”) or the expression of the E-cadherin repressor Twist in normal mammary epithelial cells that are immortalized by SV40 T-antigen and telomerase in HMLE cells (60). The loss of anoikis sensitivity was reported to accompany this EMT (68). We confirmed these effects, both in the aforementioned context and in cells that expressed both activated ras (“HMLER cells” [68]) and EMT-inducing genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The effect of E-cadherin depletion on anoikis could be reversed by the expression of (shRNA-resistant) mouse E-cadherin (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), confirming the specificity of the E-cadherin knockdown. Accompanying EMT, the ankyrin-G protein, which colocalized with E-cadherin (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material) as reported previously (50), was downregulated, reflecting the levels of ank3 mRNA transcript (Fig. 1a). Activated ras alone did not downregulate ankyrin-G, indicating that this effect was a consequence of EMT rather than activated growth factor signaling pathways. Ankyrin-G was also downregulated specifically in the “claudin-low” subclass of breast tumors (as defined in reference 39), a subclass that has an EMT-like gene expression signature (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 1.

Ankyrin-G is downregulated by EMT and regulates anoikis sensitivity. (a) Ankyrin-G is downregulated by EMT. The indicated HMLE-derived cell lines were analyzed for ankyrin-G (∼210-kDa) protein by Western blotting or for ankyrin-G mRNA by RT-PCR. (b) Ankyrin-G promotes anoikis sensitivity: siRNA depletion in normal epithelial cells. HMLER cells transfected with two ankyrin-G siRNAs were assayed for anoikis. Western blotting (lower panel) confirmed the knockdown of ankyrin-G. (c) Ankyrin-G promotes anoikis sensitivity: ankyrin reexpression in EMT-derived cells. HMLE+shEcad cells or HMLE+shEcad+ankyrinΔMBD-CAAX cells were assayed for anoikis.

Partial depletion of ankyrin-G with two distinct siRNAs protected HMLER cells against anoikis as assayed by DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1b). Ankyrin-G depletion in HMLE cells was toxic, indicating that activated ras or other cell context-dependent factors may compensate for ankyrin-G-dependent housekeeping functions (data not shown).

Conversely, the expression of full-length ankyrin-G in cells that had undergone EMT was attempted but proved unsuccessful for technical reasons. We generated a smaller version of ankyrin-G by deleting the N-terminal membrane-binding domain containing the 24 ankyrin repeats and replacing it with a C-terminal CAAX box to achieve membrane localization. The expression of this construct, AnkΔMBD-CAAX, in HMLE+shEcad cells sensitized the cells to anoikis in both DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1c) and trypan blue exclusion assays (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). These results indicated that the downregulation of ankyrin-G in EMT may be understood in terms of a cell survival effect, whose mechanism was investigated as follows.

Ankyrin-G interacts with NRAGE.

Ankyrin-G contains a conserved “supermodule” of domains (ZU5-UPA-DD) that is also found in Unc5 (99) and, having noted that the latter interacts with NRAGE (101), we tested the interaction of NRAGE with ankyrin-G. NRAGE and ankyrin-G proteins endogenous to HMLE and MCF10a cells interacted by co-IP and Western blotting (Fig. 2a). As confirmation of the specificity of the ankyrin-NRAGE coimmunoprecipitation, three additional tests were performed: (i) the specificity of the antibodies was confirmed by Western blotting of siRNA-depleted cell extracts (data not shown); (ii) immunoprecipitation of the cells containing the ankyrin construct AnkΔMBD-CAAX, which is FLAG-tagged, showed that NRAGE could be coimmunoprecipitated with ankyrin independently of ankyrin antibody (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material); and (iii) a reverse immunoprecipitation of NRAGE yielded an ankyrin-G band (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Ankyrin-G interacts with NRAGE. (a) Endogenous NRAGE–ankyrin-G interaction. Lysates of MCF10a cells or HMLE cells were immunoprecipitated with ankyrin-G pAb or nonimmune rabbit IgG (“con”) and probed for NRAGE. A no-lysate (NL) control was used to exclude IgG bands. WCL, whole-cell lysate representing 1/40 of input. (b) The MAGE and C-terminal domains of NRAGE interact with ankyrin-G. The indicated deletion mutants of NRAGE were cotransfected into 293T cells as GST fusion constructs, together with 3×HA-ankyrin p105. Western blots of glutathione-Sepharose-precipitates were analyzed for HA-ankyrin or GST-NRAGE, and each HA signal was normalized for its corresponding GST signal, producing the ratios shown in the graph. (c) The UPA domain of ankyrin-G interacts with NRAGE. The ankyrin-G domains indicated in the diagram, expressed as 3×HA-tagged proteins, were cotransfected with GST-NRAGE into 293T cells. Glutathione-Sepharose precipitates were probed for HA-ankyrin. The ratios of the HA signal in the precipitates versus the HA signal in the total lysates are shown. Note that the ankyrin repeat and ZU-5a domains were found to be dispensable for NRAGE interaction in an earlier experiment (data not shown).

Deletion mapping of the interaction domain on NRAGE for ankyrin indicated that the MAGE and WQXP domains were critical (and potentially the C-terminal tail, although this was ambiguous due to its low expression in this context), whereas other domains contributed only modestly (Fig. 2b; see also Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), a finding consistent with the previously reported interaction of the MAGE domain of NRAGE with Unc5 (101). Deletion mapping of the interaction domain on ankyrin-G yielded the surprising result that the UPA (Unc5-PIDD-ankyrin) component of the supermodule (99) was necessary and sufficient for NRAGE interaction (Fig. 2c; see also Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), in contrast to the ZU-5-mediated interaction of NRAGE with Unc5 (101). In subconfluent epithelial cells (which were used throughout the present study), ankyrin-G and NRAGE both showed diffuse cytoplasmic localization; thus, immunofluorescent colocalization studies were uninformative (data not shown). The percentage of NRAGE that complexed with ankyrin-G was calculated from image analysis (after correction for the efficiency of the ankyrin immunoprecipitation) as 34% for MCF10a and 24% for HMLE, percentages that could have been adversely affected by technical factors such as the instability of the complex in our particular buffer. As demonstrated below, ankyrin-G clearly affected NRAGE localization, indicating that this interaction was functionally significant.

Ankyrin-G sequesters NRAGE in the cytoplasm.

NRAGE interacts both with receptors and with transcription factors, indicating that its subcellular localization is likely to play an important role in its biologic functions (see the introduction); indeed, both nuclear and cytoplasmic NRAGE have been observed (2). We hypothesized that ankyrin-G might affect this localization. To test this, HT1080 cells, which have low endogenous ankyrin-G expression, were transiently cotransfected with HA-NRAGE and ankyrin-G (wild type), ankyrin-G (ΔUPA), or a control vector. Although most of the transfected NRAGE localized to the nucleus in the absence of ankyrin-G or in the presence of the non-NRAGE-binding deletion mutant ΔUPA, a significant fraction of the NRAGE was sequestered in the cytoplasm by wild-type ankyrin-G (Fig. 3a).

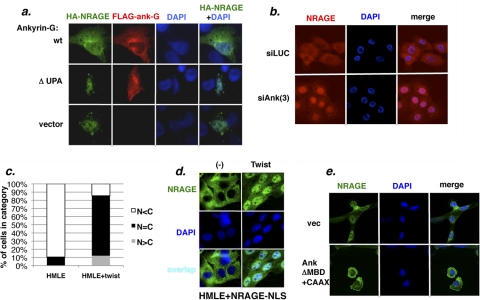

Fig. 3.

Ankyrin-G sequesters NRAGE in the cytoplasm, and EMT enhances the accumulation of NRAGE in the nucleus. (a) Overexpressed ankyrin-G sequesters NRAGE in the cytoplasm. HT1080 cells were cotransfected with expression constructs encoding FLAG–tagged human ankyrin-G (210-kDa isoform), an NRAGE-nonbinding ankyrin-G deletion mutant, ΔUPA, or empty vector, together with HA-NRAGE. The cells were then fixed and stained for FLAG-ankyrin-G, HA-NRAGE, or chromatin (DAPI). (b) Depletion of ankyrin-G facilitates the accumulation of NRAGE in the nucleus. HMLE cells were transfected with multiple siRNAs for ankyrin-G (“si-Ank”) or luciferase (“si-Luc”), treated with leptomycin B, and stained for NRAGE (red) or chromatin (DAPI, blue). For the merged images, the color intensities were adjusted to provide optimal color balance. (c) EMT enhances the nuclear localization of NRAGE. HMLE or HMLE+Twist cells expressing HA-NRAGE (at ∼2-fold above the endogenous level for Twist) were treated with leptomycin B and stained for HA or chromatin. The histogram represents the frequency of cells with mostly nuclear staining (N>C), similar nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (N∼C), or mostly cytoplasmic staining (N<C) (n = 88 for HMLE, n = 113 for Twist [P < 0.001]). (d) NRAGE-NLS is sequestered in the cytoplasm in normal cells and translocates to the nucleus in response to EMT. HMLE or HMLE+Twist cells stably transduced with an HA-NRAGE-NLS-expressing retrovirus were treated with leptomycin B and stained for NRAGE (green) and chromatin (DAPI, blue). (e) Ankyrin-G that is reexpressed in EMT-derived cells sequesters NRAGE in the cytoplasm. ΑnkyrinΔMBD+CAAX (see the text) was stably expressed in HMLE+shEcad cells, which were stained with NRAGE antibody.

To test this phenomenon in a more physiologic context, HMLE cells were depleted of ankyrin-G with several separate siRNAs, and the NRAGE localization was examined by immunofluorescence analysis. As with numerous other proteins that shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (11, 22, 35, 41, 48, 63, 72), immunofluorescent detection of nuclear NRAGE required a brief pretreatment of the cells with the export inhibitor leptomycin B prior to fixation. Depletion of ankyrin-G increased the nuclear accumulation of NRAGE protein, in contrast to the luciferase siRNA-transfected control cells (Fig. 3b; see also Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). Similar effects were seen in HMLER cells, which express levels of ankyrin-G and E-cadherin comparable to those of HMLE cells (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). To confirm the specificity of our NRAGE antibody in immunofluorescent localization assays, depletion of NRAGE with siRNA was found to reduce the fluorescent signal substantially (data not shown).

These results suggested that NRAGE nuclear localization would be enhanced in cells that have reduced ankyrin-G levels due to EMT. This expectation was confirmed by immunofluorescence analysis of NRAGE in HMLE+Twist cells, revealing that the loss of E-cadherin and, consequentially, ankyrin-G, enhanced the accumulation of NRAGE in the nucleus (Fig. 3c). In addition, a retrovirally transduced NRAGE protein that was fused to multiple SV40 T-antigen nuclear localization signals was largely cytoplasmic in HMLE cells, indicating that even in this circumstance of enforced nuclear import, ankyrin-G prevented the nuclear accumulation of NRAGE whereas, in contrast, NRAGE-NLS was mainly nuclear in (ankyrin-deficient) Twist-expressing cells (Fig. 3d). Conversely, the retroviral expression of a large fragment of ankyrin-G (lacking the membrane-binding domain but containing a CAAX box for membrane tethering) in (ankyrin-deficient) HMLE+shEcad cells sequestered endogenous or HA-tagged NRAGE in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3e; see also Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). Nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization of NRAGE could not be shown reliably using cell fractionation methods, which is consistent with previous observations that some nucleoplasmic proteins tend to leak out of the nucleus during fractionation, precluding this experimental approach (12, 25, 69). Nevertheless, the shift toward nuclear NRAGE in EMT-derived cells or in normal cells depleted of ankyrin-G, or, conversely, the shift toward cytoplasmic NRAGE upon the add-back of ankyrin-G to EMT-derived cells strongly implicated the loss of ankyrin-G in the EMT-driven NRAGE relocalization. The consequences for NRAGE function were then investigated as follows.

NRAGE is an anoikis suppressor.

EMT is frequently accompanied by the acquisition of anoikis resistance (see the introduction and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To test the potential role of NRAGE in this effect, NRAGE was depleted in cells that had undergone EMT (HMLE+shEcad and HMLE+Twist) cells using multiple si/shRNAs, and anoikis was assayed. A substantial increase in anoikis (but not spontaneous apoptosis in attached cells) was seen in these transiently NRAGE-depleted cell lines by DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4a and b), caspase activation and trypan blue exclusion assays (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). Cell morphology and E-cadherin expression did not indicate a reversal of EMT in these siRNA-transfected cells (data not shown). The HMLE+Twist cells, which had previously been reported to generate mammospheres due to their cancer stem cell-like nature, showed reduced mammosphere generation and, correspondingly, reduced soft agar colony formation, presumably due to increased anoikis sensitivity, upon the depletion of NRAGE (see Fig. S12 and S13 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 4.

NRAGE is an anoikis suppressor. (a) NRAGE depletion sensitizes HMLE+shEcad cells to anoikis. HMLE+shEcad cells were transfected with a pool of four siRNAs (upper panel) or a distinct additional siRNA (NRAGE-S2) and assayed for anoikis. (b) NRAGE depletion sensitizes HMLE+Twist cells to anoikis. HMLE+Twist cells were transfected with a pool of four siRNAs (upper panel) or infected with a doxycycline-inducible NRAGE shRNA lentivirus and grown for 3 days in the presence or absence of doxycycline (lower panel) and assayed for anoikis.

Anoikis-suppressive effects of NRAGE were also observed in the lung carcinoma cell line NCI-H1299 and in the breast carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-435; the latter also showed compromised anchorage-independent colony formation upon the suppression of NRAGE, indicating the applicability of this mechanism to naturally occurring, E-cadherin-negative tumor cells that expressed high levels of NRAGE and low levels of ankyrin-G (see Fig. S14 in the supplemental material).

The anoikis-suppressive effect of NRAGE was paradoxical in light of its previously reported proapoptotic functions (5, 20, 101), prompting us to compare its expression levels in human tumors with normal tissues, in that the loss of a proapoptotic protein or gain of an antiapoptotic protein is advantageous for tumor progression. Through the use of quantitative RT-PCR (TaqMan) on panels of tumor or normal tissue-derived cDNAs, NRAGE was found to be overexpressed at all stages of breast cancer, especially stages I and III (Fig. 5a) and at all stages of lung cancer, although the breast cancer results fluctuated stage dependently, whereas the lung cancer results showed a tonic-stage-dependent increase (Fig. 5a and b). Analysis of NRAGE protein levels by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA), a quantitative, two-color immunofluorescence technology (8), showed a statistically significant upregulation of NRAGE protein in colorectal cancer (Fig. 5c; see also Fig. S15 in the supplemental material), as well as in metastatic melanoma (Fig. 5d). Upregulation was also observed in prostate cancer (Fig. 5e), although the statistical significance was P < 0.08. Validation of the NRAGE detection was afforded by the NRAGE siRNA depletion experiment above, as well as correlation between expression of the protein by AQUA with expression of the mRNA (extracted from Oncomine data) across six cell lines (see Fig. S16 in the supplemental material). NRAGE was also induced by EMT in the HMLE cells (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

NRAGE is overexpressed in certain cancer types. (a) NRAGE mRNA is overexpressed in breast cancer. A panel of 5 normal and 43 breast cancer cDNAs was probed using TaqMan for NRAGE. β-Actin-normalized expression units are shown. (b) NRAGE mRNA is overexpressed in lung cancer. A panel of 8 normal and 40 lung cancer cDNAs was probed using TaqMan for NRAGE. β-Actin-normalized expression units are shown. (c) NRAGE protein is overexpressed in colon cancer. A tissue microarray containing 19 colon cancer samples and 6 normal samples was probed and quantitated by using AQUA (P < 0.006). (d) NRAGE protein is overexpressed in melanoma metastases. A tissue microarray containing samples of normal nevi (n = 8), primary melanoma (n = 9), or metastatic melanoma (n = 9) was probed and quantitated using AQUA (P < 0.009 for the difference in metastases versus nevi). (e) NRAGE protein is overexpressed in prostate cancer. A tissue microarray containing 17 prostate cancer samples and 6 normal samples was probed and quantitated by using AQUA (P < 0.08). (f). EMT upregulates NRAGE expression. HMLE cells or derivates expressing E-cadherin shRNA (“HMLE/shEcad”) or the Twist oncogene (“HMLE/Twist”) were probed for expression of NRAGE or, as a loading control, β-actin.

The overexpression of NRAGE in various tumors, while not necessarily critical for anoikis regulation, was conceptually more consistent with the functional role of NRAGE as an anoikis suppressor rather than an apoptosis promoter in tumors. The mechanism of anoikis suppression by NRAGE was then explored, as described below.

NRAGE interacts with TBX2.

The interaction partners previously reported for NRAGE failed to explain how NRAGE might suppress anoikis. To address this mechanism, a yeast two-hybrid interaction was performed. Several candidate proteins were identified, including TBX2, KIAA0676, DAZAP2, DOCK6 and, in agreement with previous reports (84), the ubiquitin ligase Praja2. In light of the oncogenic activities of TBX2 (see the introduction), we investigated this interaction further.

The interaction between TBX2 and NRAGE was confirmed by co-IP of endogenous lysates of HMLE+shEcad cells with NRAGE antibody (Fig. 6a). The reverse co-IP was found to be less reliable, due to the poor IP efficiency of available TBX2 antibodies.

Fig. 6.

NRAGE interacts with TBX2, with functional consequences for anoikis sensitivity. (a). Endogenous interaction. HMLE+shEcad cells were immunoprecipitated with NRAGE pAb (“NR”) or an equal amount of control rabbit IgG (“Con”), and immunoprecipitates or total lysates were analyzed on a Western blot for TBX2 or NRAGE. (b) The C-terminal domain of NRAGE interacts with TBX2. The indicated deletion mutants (diagrammed in Fig. 2) of GST-NRAGE were cotransfected with FLAG-TBX2, and protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with FLAG antibody and analyzed on a Western blot for FLAG and GST. The ratios of GST to FLAG signal were quantitated and plotted to indicate the relative degree of interaction for each deletion construct, normalized against the expression level of each NRAGE deletion mutant (arbitrary units). (c) The repression domain of TBX2 interacts with NRAGE. 293T cells were cotransfected with expression constructs containing the indicated FLAG-tagged TBX2 constructs, and FLAG-agarose precipitates were analyzed for endogenous NRAGE protein by Western blotting. (d) NRAGE-TBX2 interaction mediates protection against anoikis. NRAGE−/− MEFs that were rescued with wild-type NRAGE (WT) or with the C-terminal deletion mutant that failed to interact with TBX2 (ΔC) were assayed for anoikis. (e) TBX2 is an anoikis suppressor. HMLE+shEcad cells transfected with TBX2 siRNA (Smartpool) or luciferase siRNA were assayed for anoikis at 8 h of suspension. Note that the efficiency of TBX2 knockdown (Western blot in the inset) correlated well with the magnitude of protection against anoikis.

To map the interaction site on NRAGE for TBX2, individual domains were deleted and expressed as epitope-tagged proteins by cotransfection into 293T cells, together with full-length FLAG-TBX2. The C-terminal ∼120-amino-acid domain of unknown function (which is, however, highly conserved among species and between MAGE-D family members [15]) was critical for the interaction, with a minor contribution from the central domain containing 21 repeats of the sequence W(Q/P)XP (Fig. 6b; see also Fig. S17 in the supplemental material).

A domain in mouse TBX2 that represses transcription overlaps partially with a defined repression domain in TBX3 (9, 71) and with a fragment (in human TBX2) that was identified by interaction in the yeast two-hybrid screen (data not shown). TBX2's interaction with NRAGE was abrogated by the deletion of this domain (Fig. 6c).

These results suggested that NRAGE potentially regulated anoikis through an interaction with the oncogenic transcriptional repressor TBX2. Consistent with this idea, the reexpression of full-length NRAGE but not a deletion mutant lacking the TBX2-interaction domain (C terminus) protected NRAGE-knockout MEFs against anoikis (Fig. 6d). Moreover, partial (∼2-fold) depletion of the (highly abundant) TBX2 protein in HMLE+shEcad cells enhanced anoikis, indicating that TBX2 was, like NRAGE, an anoikis suppressor (Fig. 6e). Similar results were obtained with a second, distinct set of siRNAs or by the use of an annexin V staining assay (data not shown).

As another test of the functional relationship between TBX2 and NRAGE, we expressed TBX2 ectopically in SW13 adrenocortical carcinoma cells, in which TBX2 has previously been reported to confer anchorage-independent growth (42). NRAGE was then stably depleted using shRNA retroviral vectors in the TBX2/SW13 cells, which were assayed for growth in soft agar. Depletion of NRAGE suppressed anchorage-independent growth (see Fig. S18 in the supplemental material) but not normal growth under attached conditions (data not shown), reinforcing the view that TBX2 conferred anchorage independence through NRAGE.

Interdependence of NRAGE and TBX2 for the repression of a TBX2-target gene, p14ARF.

We explored the functional significance of the NRAGE-TBX2 interaction further by testing the role of NRAGE in TBX2-mediated transcriptional repression. TBX2 is a transcriptional repressor of p14ARF, p21, and E-cadherin (45, 74, 80). Of these, the p14ARF promoter interaction is the best characterized (57, 79).

Using a pool of four siRNAs and one inducible shRNA, p14ARF protein was induced by the depletion of NRAGE protein in two EMT-derived cell lines, HMLE+shEcad and HMLE+Twist, as well as in MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma and NCI-H1299 lung carcinoma cells (Fig. 7a). To examine additional cell lines, further exclude off-target effects, and show that the p14ARF induction was transcriptional, the p14ARF protein and mRNA were also found to be inducible by NRAGE siRNA in HMLER, HMLER+shEcad, and HMLER+Twist cells (see Fig. S19 in the supplemental material).

Fig. 7.

NRAGE represses p14ARF expression in cells resulting from EMT and tumor cell lines. (a) HMLE cell lines expressing shEcad or Twist (upper panel), MDA-MB-435 breast carcinoma cells, or NCI-H1299 lung carcinoma cells (middle panel) were transfected with NRAGE Smartpool siRNA and analyzed for p14ARF protein induction. The normalized fold induction relative to the caspase-8 control is shown. For the lower panel, HMLE+Twist cells that expressed a doxycycline-inducible lentiviral NRAGE shRNA construct were assayed for p14ARF expression with or without doxycycline induction. (b) NRAGE cooperates with TBX2 to repress the p14ARF promoter. For the left panel, the Gal4-TBX2-repression domain (amino acids 515 to 574) was cotransfected at the indicated input DNA amounts with a Gal4-thymidine kinase-luciferase reporter into HMLE+shEcad cells that had been depleted of endogenous NRAGE with Smartpool siRNA or a nontargeting (NT) control siRNA. For the right panel, TBX2 was cotransfected at the indicated input DNA amounts with an ARF promoter-luciferase construct, with wild-type (first four pairs) or mutant TBX2 (fifth pair) binding sites, into 293T cells. The fold repression in cells pretransfected with control siRNA or NRAGE siRNA is shown at various input amounts of Gal4-TBX2-RD or TBX2 DNA. The enhancement of repression was calculated by dividing the fold repression due to Gal4-TBX2-RD in the control-siRNA samples by the fold repression due to Gal4-TBX2-RD in the NRAGE-siRNA samples. The results are averaged over two independent experiments. (c) TBX2 recruits NRAGE to the p14ARF promoter. For the left-hand panel, 293T cells were cotransfected with p14ARF-luciferase constructs containing the wild-type promoter (wt) or a mutant promoter (mut) lacking the previously characterized TBX2 binding site. FLAG-NRAGE and untagged TBX2 were cotransfected as indicated, and ChIP analysis was performed on FLAG-agarose precipitates. For the right-hand panel, a 3×Gal4-thymidine kinase promoter-luciferase construct was cotransfected with Gal4-TBX2 and FLAG-NRAGE, followed by ChIP analysis as described above. (d) EMT increases the occupancy of the p14ARF promoter by NRAGE. HMLE or HMLE+Twist cells that expressed similar levels of 3×FLAG-NRAGE (Western blot, right) were analyzed by ChIP using a FLAG antibody, a histone H3 antibody (as a positive control), or an HA antibody (as a negative control) and PCR primers spanning the TBX2 binding site of the p14ARF promoter.

These results suggested that NRAGE acted as a corepressor for the repressor protein TBX2. Reporter assays were performed using a Gal4-TBX2 (full-length) or Gal4-TBX2-repression domain (RD; amino acids 515 to 574; overlapping with the NRAGE binding site; Fig. 6c) in HMLE+shEcad cells that had been depleted of endogenous NRAGE prior to cotransfection of a Gal4-thymidine kinase-luciferase reporter construct, since this approach yielded more consistent results than overexpression of NRAGE (due to the modest overexpression factor of this protein, even in cytomegalovirus [CMV] vectors). This approach also focused specifically on TBX2 repressor activity, avoiding confounding effects due to other elements of the ARF promoter that may occur in transient transfections. Consistently, over a range of Gal4-TBX2-RD input DNA concentrations, TBX2 repressed transcription more efficiently in cells transfected with control siRNA compared to NRAGE siRNA (Fig. 7b), confirming that NRAGE promoted the repressive activity of TBX2; similar results were obtained with Gal4-TBX2 (full-length) or with 293T cells (data not shown). Similar results were also obtained using an ARF promoter-luciferase construct in siRNA-transfected 293T cells, where repression by TBX2 was dependent upon the endogenous NRAGE, cotransfected TBX2 and a wild-type TBX2 binding site on the promoter (Fig. 7b).

To test the idea that NRAGE was a corepressor for TBX2 on the ARF promoter, ChIP data revealed that NRAGE that was transfected into 293T cells (which are devoid of TBX2 [data not shown]) was recruited to the p14ARF promoter only in the presence of cotransfected TBX2 and a wild-type TBX2 binding site on the promoter (Fig. 7c). Similar results were obtained for the recruitment of a Gal4-TBX2 fusion protein to a Gal4-thymidine kinase promoter. To test the effect of EMT on the interaction of NRAGE with the p14ARF promoter by ChIP, in light of the incompatibility of NRAGE antibodies with ChIP assays, we generated HMLE or HMLE+Twist cells that expressed 3×FLAG-tagged NRAGE by retroviral transduction, which expressed NRAGE at levels ∼3-fold above the endogenous level (in Twist cells), minimizing the chances of artifactual overexpression effects. When analyzed by ChIP with FLAG antibody, substantially more NRAGE was bound to the ARF promoter in the Twist cells than in the HMLE cells (Fig. 7d). As a positive control, histone H3 antibody immunoprecipitated similar p14ARF promoter DNA in both cell lines. This increased NRAGE occupancy on the ARF promoter correlated with the increased nuclear localization and repression of p14ARF in response to Twist expression shown above.

These results indicated that NRAGE acted as a corepressor for TBX2 to suppress p14ARF expression and suggested that ankyrin-G could regulate p14ARF, perhaps providing a mechanism to regulate anoikis sensitivity, which was investigated as follows.

EMT and ankyrin-G regulate p14ARF.

Based on the evidence presented above, we predicted that the sequestration of NRAGE by ankyrin-G would alleviate the repression of p14ARF, i.e., upregulate it. First, we assayed for p14ARF in HMLE cells that had reduced ankyrin-G due to EMT. Endogenous p14ARF expression was downregulated in both cell lines (Fig. 8a). To determine whether this effect could be attributed to ankyrin-G loss, ectopic expression of the ankyrinΔMBD-CAAX protein caused NRAGE to relocalize to the cytoplasm (Fig. 3e), induced p14ARF expression (Fig. 8b), and sensitized the cells to anoikis (Fig. 1c; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). When combined, these data indicated that EMT controlled ARF expression through ankyrin-G.

Fig. 8.

p14ARF is downregulated by EMT and upregulated by ankyrin-G. (a) Downregulation by EMT. HMLE cells expressing shEcad (analyzed on one Western blot) or Twist (analyzed on another Western blot) were assayed for p14ARF protein (left panel) or mRNA (right panel). (b) Upregulation by ankyrin-G. HMLE+shEcad cells that express the ankyrinΔMBD-CAAX construct (see the text) were assayed for p14ARF protein expression. The normalized fold induction is shown.

These data predicted a potential positive correlation between ankyrin-G and ARF expression in subclasses of tumors or tumor cell lines where this pathway played a predominant role. To facilitate the identification of the relevant subclasses, we focused on microarray data sets that classified samples by gene expression signatures rather than pathological criteria. For breast cancer, both tumor (39) and cell line (66) data meeting this criterion have been published, but only the latter study used a microarray platform containing probes specific for exon 1β, reporting p14ARF mRNA specifically (rather than p14ARF plus p16INK4a overlapping sequences). Both ankyrin-G and p14ARF were highly downregulated in Basal B (EMT-like, vimentin-positive) breast cancer cell lines compared to Basal A (K5/K14-positive epithelial), with a statistically significant correlation (R = 0.4, P < 0.036) across this panel of 30 cell lines (see Fig. S20 in the supplemental material). No correlation was found with respect to luminal cell lines, indicating that the ankyrin-ARF functional interaction is relevant to basal, but not luminal breast cancer.

P14ARF promotes anoikis, and NRAGE suppresses anoikis by repressing p14ARF expression.

In light of the anoikis-suppressive effects of TBX2 and NRAGE, the proapoptotic activities of p14ARF in certain other contexts (see the introduction), and the tumor suppressor activity of p14ARF, we hypothesized that p14ARF promoted anoikis sensitivity.

Specific depletion of p14ARF mRNA/protein (without affecting p16 expression) using an exon 1β-specific siRNA partially protected against anoikis, suggesting that the p14ARF tumor suppressor gene plays an important role in anoikis (Fig. 9a). To test the effect of p14ARF on anoikis in another context, we used p19ARF-knockout (p19ARF being the mouse homologue of human p14ARF) MEFs or matched wild-type control MEFs. The p19ARF-knockout MEFs were markedly resistant to anoikis compared to wild-type MEFs, assayed either by DNA fragmentation (Fig. 9b) or by caspase activation (see Fig. S21 in the supplemental material), confirming that p14ARF/p19ARF promoted anoikis and indicating a novel function for this tumor suppressor gene.

Fig. 9.

p14ARF promotes anoikis sensitivity, and NRAGE confers anoikis resistance by suppressing p14ARF. (a) siRNA-mediated depletion of p14ARF confers anoikis resistance. HMLER cells transfected with a p14ARF exon 1β-specific siRNA that did not target p16 were assayed for anoikis at 24 h of suspension. Confirmation of the knockdown is shown in the lower panel. (b) ARF−/− and matched ARF+/+ MEFs were assayed for anoikis at 6 or 24 h of suspension. (c) NRAGE confers anoikis resistance by suppressing p14ARF (double-knockdown approach). HMLE+Twist cells that were depleted of NRAGE, p14ARF, or both were assayed for anoikis and p14ARF expression. (d) NRAGE confers anoikis resistance by suppressing p14ARF (complementation approach). HMLE+Twist-ER cells (induced to undergo EMT with 4-OHT) that expressed a doxycycline-inducible 6×HA-p14ARF construct were induced with doxycycline and assayed for anoikis compared against a control cell line with the empty vector. The Western blot shows that the induced level of 6×HA-p14ARF was similar to that expressed by HMLE-Twist cells prior to EMT induction.

These results indicated that the NRAGE-TBX2 complex suppressed anoikis at least in part by repressing p14ARF expression. To confirm this, HMLER+Twist cells were transfected with NRAGE siRNA, p14ARF siRNA, or both siRNAs. The depletion of NRAGE was able to sensitize the cells to anoikis and upregulate p14ARF. In contrast, cells in which ARF had been depleted were unaffected by NRAGE siRNA (Fig. 9c), confirming that NRAGE regulates anoikis sensitivity through p14ARF. Moreover, the ectopic expression of p14ARF protein in HMLE+Twist cells (that expressed high endogenous levels of NRAGE/TBX2 and low levels of ankyrin-G) sensitized them to anoikis, further indicating the importance of p14ARF as an NRAGE target gene that promotes anoikis (Fig. 9d).

DISCUSSION

EMT correlates tightly with anoikis resistance (51, 54, 89). The causes of both EMT and anoikis resistance are diverse. Oncogenes that drive EMT (e.g., Snail, Slug, ZEB1/2, and Twist) frequently downregulate E-cadherin and confer anoikis resistance. Although these genes do not necessarily affect anoikis through E-cadherin (in fact, they control pro-/antiapoptotic gene expression directly as well [3, 94]), the loss of E-cadherin is a major landmark in the stepwise progression of EMT, and recent evidence from a mouse mammary tumor model and stable knockdown cell lines indicates that E-cadherin is, at least in some instances, necessary, although probably not sufficient, for epithelial cells to be anoikis sensitive (19, 68).

A mechanism for the transcriptional control of cellular susceptibility to anoikis by EMT via E-cadherin is depicted in Fig. 10. In normal epithelial cells, ankyrin-G sequesters NRAGE in the cytoplasm. In cells that have undergone EMT, ankyrin-G expression is suppressed (34), permitting a fraction of NRAGE to translocate to the nucleus. There, NRAGE interacts with TBX2 to repress the p14ARF promoter (as well as other target gene promoters not yet identified), attenuating anoikis sensitivity, so that the cells undergo less apoptosis upon a subsequent challenge with cell matrix detachment.

Fig. 10.

Pathway leading from EMT to anoikis resistance.

This mechanism, in its current form, is distinct from (but not mutually exclusive with) the previously characterized β-catenin/APC/GSK-3/LEF1 pathway, which was examined previously with regard to anoikis resistance in E-cadherin knockdown cells and found to partially account for anoikis resistance (68). In this connection, we did not observe the relocalization of β-catenin to the nucleus in cells depleted of ankyrin-G (data not shown). We do not, however, exclude the possibility that the pathway elucidated here may interact functionally, in either direction, with the Wnt pathway. In addition, the loss of the Scribble cell polarity protein has recently been shown to suppress c-myc-driven apoptosis in an acinar morphogenesis assay in MCF10a cells. Because Scribble function is partly dependent upon E-cadherin (64), our results do not exclude the possibility that the Scribble/β-PIX/Rac/JNK apoptosis pathway described by Zhan et al. (104) could also play a role in EMT-induced anoikis resistance, potentially through interactions with components of the new pathway described here.

The data presented here demonstrate that NRAGE is overexpressed in several tumor types, and there are previous reports of NRAGE overexpression in lung, kidney, and head or neck cancer (6, 7, 33). This observation is consistent with an antiapoptotic role of NRAGE in cancer, in contrast to its proapoptotic function in normal neuronal cells. In this connection, our results suggest that NRAGE is potentially oncogenic and/or prometastatic. Intriguingly, a prometastatic role of the related MAGE-D3/trophinin gene in colorectal carcinoma (38) has been shown previously. In apparent contradiction, NRAGE inhibited metastasis in a pancreatic cancer cell line and a growth-arrested a breast cancer cell line, but the high-level adenoviral expression used in those studies may have produced nonphysiologic effects (16, 21). In light of its anoikis and anchorage dependence effects, testing the predicted oncogenic activity of NRAGE in an appropriate mouse model will be an interesting future goal.

The loss of ankyrin-G expression during EMT is a key event with regard to the pathway proposed here. A recent large-scale gene expression profiling study indicated that the downregulation of the ank3 gene encoding ankyrin-G is one component of an 11-gene signature characteristic of chemoresistant “stem cell-like” tumors from a broad spectrum of human tumor types (34). The mechanism of this downregulation is not yet understood. Downregulation of ankyrin-G, p14ARF and of anoikis sensitivity were conferred coordinately by Twist or E-cadherin depletion in the HMLE system and, while the present report was in review, a supplemental microarray table listed the ank3 gene as a target gene downregulated by other EMT-inducing factors, transforming growth factor β, Goosecoid, and Snail (90). The mechanism of ankyrin-G downregulation during EMT remains to be investigated.

TBX2 is overexpressed in most melanomas and BRCA1-null breast cancers (59, 81, 93). Its potent immortalizing (i.e., anti-senescence) activity, which may be related to the stem-cell self-renewal activity of TBX3, has been attributed to its transcriptional repression of the p21 and p14ARF (p19ARF in mice) promoters (45, 74, 93). E-cadherin is another target of TBX2/3 in melanoma cells (80), but we did not observe any effects of TBX2 nor NRAGE on E-cadherin in the cell lines used here, indicating cell context specificity (data not shown). The mechanism of repression by TBX2 is not yet understood, since it has no recognized corepressor recruitment domains, although a dominant-negative TBX2 mutant can activate transcription by displacing a histone deacetylase activity from the p21 promoter (93). Here, the minimal repression domains of TBX2 and TBX3 (data not shown) were found to interact with NRAGE. NRAGE supported TBX2-mediated repression of the p14ARF gene and was recruited to the p14ARF promoter in a TBX2-dependent manner, implicating NRAGE as a TBX2/3 corepressor. Several corepressors play an important role in tumor progression, including KAP-1, CtBP, and Ajuba, and evidence for regulation of some of these factors by nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization has been found (1, 14, 56, 97, 98). As with other corepressors, NRAGE is likely to target multiple genes for repression; preliminary data (not shown) indicate, for example, that NRAGE also represses the TBX2-target gene, N-myc downregulated gene 1 (NDRG1), a proliferation and apoptosis regulator (78).

Our results indicate that p14ARF—one of the most commonly mutated, silenced or deleted tumor suppressor genes in human cancer (47)—promotes anoikis. This provides a novel rationale for the loss of function of this gene in tumors. In this connection, a loss of heterozygosity of the CDKN2a locus promotes tumor progression significantly in both mouse and human contexts, revealing a haploinsufficiency effect and validating the importance of the ∼2-fold regulation of p14ARF expression observed here (24, 40, 52, 62). The pro-anoikis effect of p14ARF also may explain the advantage to tumor cells of overexpressing TBX2/3 and/or NRAGE proteins—repressors of p14ARF that counteract anoikis and promote anchorage-independent growth (10, 42, 96)—or other repressors of p14ARF (49). In addition, TBX3 expression and ARF downregulation are key components of embryonic stem cell proliferation and induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) generation, respectively (55, 67). The expression of Twist has previously been shown to endow HMLE cells with the cancer stem cell phenotype of mammosphere formation, which would appear to require anchorage-independent growth and abrogation of anoikis (60). These considerations may implicate NRAGE in the cell survival of both iPS and cancer stem cells. In this connection, Twist has previously been shown to downregulate p14ARF, although a direct Twist-p14ARF promoter interaction has not been reported (58); our results raise the possibility that the downregulation of E-cadherin/ankyrin-G may mediate this effect of Twist on p14ARF.

The mechanism of anoikis sensitization by p14ARF remains to be explored. Anoikis appears to be generally p53-independent (S. M. Frisch, unpublished data), with the notable exception of epithelial cells with a constitutively activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase protein (13). Consistent with this, p14ARF affected anoikis even in cell lines that expressed SV40 T-antigen, in which p53 is dysfunctional. Accordingly, we favor a model in which p14ARF promotes anoikis through its other proapoptotic pathways, for example, through c-myc, the mitochondrial protein p32, or C-terminal binding protein (37, 43, 70).

The molecular pathway described here implicates NRAGE, TBX2, p14ARF, and ankyrin-G in a novel mechanism for the control of anoikis sensitivity by EMT and E-cadherin.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert Weinberg, Peter Stoilov, Colin Goding, Vann Bennett, Krish Kizhatil, Deborah Anderson, Ken Watanabe, Keith Robertson, Peter Hurlin, Taosheng Huang, James Reecy, Srikumar Othumpangat, Laura Gibson, Lindsay Hinck, Prasad Devarajan, Kathy Brundage, Karen Martin, Mike Ruppert, Sendurai Mani, Richard Myers, and Ned Sharpless for reagents, cell lines, and advice. In particular, we thank Alexey Ivanov for significant technical advice and reagents and Jim Denvir for statistical analyses. We also thank Mike Ruppert and Mike Schaller for critical reading of the manuscript.

S.M.F. was supported by a component of an NIH COBRE grant (P20 RR16440) and by NIH grant R01CA123359. The flow cytometry core facility (Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center) was supported by NIH grants RR020866 and P20 RR16440.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 11 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ayyanathan K., et al. 2007. The Ajuba LIM domain protein is a corepressor for SNAG domain mediated repression and participates in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Cancer Res. 67:9097–9106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barker P. A., Salehi A. 2002. The MAGE proteins: emerging roles in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and neurogenetic disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 67:705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrallo-Gimeno A., Nieto M. A. 2005. The Snail genes as inducers of cell movement and survival: implications in development and cancer. Development 132:3151–3161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartel P. L., Fields S. 1995. Analyzing protein-protein interactions using two-hybrid system. Methods Enzymol. 254:241–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bertrand M. J., et al. 2008. NRAGE, a p75NTR adaptor protein, is required for developmental apoptosis in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 15:1921–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhattacharjee A., et al. 2001. Classification of human lung carcinomas by mRNA expression profiling reveals distinct adenocarcinoma subclasses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:13790–13795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boer J. M., et al. 2001. Identification and classification of differentially expressed genes in renal cell carcinoma by expression profiling on a global human 31,500-element cDNA array. Genome Res. 11:1861–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]