Abstract

Although the calpain-calpastatin system has been implicated in a number of pathological conditions, its normal physiological role remains largely unknown. To investigate the functions of this system, we generated conventional and conditional calpain-2 knockout mice. The conventional calpain-2 knockout embryos died around embryonic day 15, preceded by cell death associated with caspase activation and DNA fragmentation in placental trophoblasts. In contrast, conditional knockout mice in which calpain-2 is expressed in the placenta but not in the fetus were spared. These results suggest that calpain-2 contributes to trophoblast survival via suppression of caspase activation. Double-knockout mice also deficient in calpain-1 and calpastatin resulted in accelerated and rescued embryonic lethality, respectively, suggesting that calpain-1 and -2 at least in part share similar in vivo functions under the control of calpastatin. Triple-knockout mice exhibited early embryonic lethality, a finding consistent with the notion that this protease system is vital for embryonic survival.

INTRODUCTION

The calpain-calpastatin system, ubiquitously expressed in most tissues of vertebrates, mainly consists of calpain-1, calpain-2, and calpastatin, a specific inhibitor protein that suppresses the proteolytic activity of both the isozymes (12, 34). Calpain-1 and -2 require micro- and millimolar concentrations of calcium ion, respectively, to produce a biochemical reaction in vitro. Calpain exists as a stoichiometric heterodimer composed of a distinct catalytic subunit with a molecular mass of ∼80 kDa and an identical regulatory subunit of ∼30 kDa. The catalytic subunits of calpain-1 and -2 are encoded by the genes Capn1 and Capn2, respectively, whereas the regulatory subunit is encoded by Capns1. In general, calpain cleaves substrates at a hinge region between neighboring functional and regulatory domains, leading to activation, inactivation, or destruction of the substrate proteins. Recently, more than 10 calpain isoforms have been identified in mammals (29).

The calpain-calpastatin system has been shown to participate in a number of pathological conditions, including hypoxia, ischemia, spinal cord injury, Alzheimer's disease, muscular dystrophy, cataract, and lissencephaly (26, 36, 39). This is reflected in the finding that calpastatin deficiency enhances amyloidosis, inflammation, and neuronal atrophy in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (M. Higuchi and T. C. Saido, unpublished data). In contrast, the normal physiological functions of calpain remain largely unresolved, although there is indirect evidence for its involvement in cell death, differentiation, development, and memory formation (5, 6, 9). However, to date calpain activation has only been detected under pathological or artificial conditions. One intrinsic problem is the absence of a solely calpain-specific low-molecular-weight inhibitor, with most previous studies of the physiological functions of calpain relying on less-specific synthetic inhibitors, leaving open the possibility that other proteases, such as cathepsin B, H, L, S, and K, might be involved (16).

To overcome these drawbacks, genetically modified mice deficient in components of the calpain system were generated. Capns1 deficiency led to the disappearance of both calpain-1 and -2 at the protein level, resulting in embryonic lethality around embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5) supposedly due to cardiac defects and hemorrhages (2). This provided the first indication that the calpain system is essential for embryonic development. In contrast, Capn1 knockout (KO) mice did not show any prominent defects in fertility, development, or anatomy except for the fact that platelet aggregation and integrin β3 phosphorylation were somewhat restricted (3). These observations surprised long-term investigators in the field, as calpain-1 had been predicted to be physiologically more important than calpain-2 based on its higher sensitivity for calcium.

The situation regarding calpain-2 remained more complex. Capn2 KO mice were reported to die in the preimplantation stage, at E2.5 (7). However, this appeared contradictory to the phenotype of the Capns1 KO mice, in which both calpain-1 and -2 are absent, given that the Capns1 KO embryos died much later, at E10.5 (2). Although this discrepancy has not yet been resolved, the results suggested the relatively greater importance of calpain-2 compared to calpain-1 in physiological terms. How then can calpain-2 be activated in vivo? Several mechanisms were initially proposed, including autocleavage of the N-terminal regulatory domain, translocation to phospholipid membranes, and dissociation of the regulatory subunit (31). More recently, phosphorylation by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase A has emerged as a candidate mechanism for regulating the activation status of calpain-2 (11, 28).

Another way to investigate the function of calpain is to manipulate the expression of calpastatin (Cast), which led us to generate Cast KO mice and transgenic (Tg) mice that overexpress calpastatin using the Camk2a promoter (17, 32). Both phenotypes were essentially normal in terms of their reproduction, development, growth, anatomy, and cognition, although the Cast KO mice exhibited modest abnormality in affective behavior (24). In contrast, calpastatin deficiency augmented excitotoxic neurodegeneration, which in turn was suppressed by calpastatin overexpression (17, 32). Thus, calpastatin appeared to play a more significant role under pathological rather than physiological conditions.

In summary, recent reverse genetic studies have highlighted the potential physiological importance of calpain-2. Here, we independently generated conventional and conditional Capn2 KO mice and found that Capn2 deficiency does not affect embryonic survival at the preimplantation stage but rather induces cell death in placental trophoblasts at later stages, followed by cardiovascular defects. However, calpain has been known as an executer of cell death, these results suggest that both calpain-1 and -2 also have a role in cell survival signaling or maintenance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation and characterization of Capn2 conventional and conditional KO mice.

The 10-kb targeting region from introns 2 to 10 of mouse calpain-2 gene was subcloned by PCR using the primers 5′-GGGTTGTGGAGCACTGCACACTTTGTAGTTTTCCGCTGCAACCATTTGCTGTTCTCC-3′ and 5′-CTTTGCATTTGCCAAGGGGTGGGGGCCAAAAGACAGGCAGTGTGGGAAGATGGAGC-3′ with 129/SvEv mouse strain bacterial artificial chromosome as a template. For the Capn2 KO, exons 3 to 7 were replaced with a neomycin resistance gene cassette with phosphoglycerate kinase promoter and polyadenylation regions to disrupt the catalytic triad of Cys105, His262, and Asn286 and make a frameshift mutation. For the Capn2 conditional KO (cKO), exon 3 was flanked between a loxP sequence and a loxP-flanked neomycin resistance gene cassette. The targeting vectors were linearized and transfected by electroporation into embryonic stem cells derived from the 129 SvEv mouse strain.

After G418 treatment for the selection of the neomycin resistance gene-introduced clones, Southern blotting was performed to identify targeted clones using Capn2-specific probes, which were generated by genomic PCR using the primers 5′-TTGGAAGTCTGACAGCCAATAAAGC-3′ and 5′-TGAAGCCAGACCTGGCTTACAGTATTCC-3′ for the 5′ probe, the primers 5′-TCCTGAGATTTATACTGTGCCAGTGG-3′ and 5′-TTTAGATGGAGTGCTACTGACAGAGG-3′ for the 3′ probe, and the primers 5′-CCCAGGTTTGGACTCAGAGACTG-3′ and 5′-TCTACATTGCATCTATGAAGATGTG-3′ for the C probe. Identified embryonic stem clones were microinjected into C57BL/6J blastocysts.

For embryonic analysis, noon of the day when a vaginal plug was recorded was considered to represent E0.5. To identify Capn2 KOs, PCR genotyping was carried out using the three primers 5′-GAGAGTTCTGAGTTTCTCAGAGAACGAACC-3′, 5′-AACTCCACGCCGTTCGGATGG-3′, and 5′-TGCGAGGCCAGAGGCCACTTGTGTAGC-3′. For Capn2 cKOs, the 5′-GCTTGGCTTGCTCCTACACTCC-3′ and 5′-GCTCATCTGTGTCTCCAAAGCC-3′ primers were used with the Acta2 primers 5′-GACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGAT-3′ and 5′-TTGCTGATCCACATCTGCTG-3′. For Cre-expressing mice, the 5′-CGCAGAACCTGAAGATGTTC-3′ and 5′-CGAAATCAGTGCGTTCGAAC-3′ primers were used with the Gapdh primers 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTG-3′. EIIa-, Meox2-, and Tek-Cre expressing mice (stock numbers 003724, 003755, and 004128, respectively) were provided by the Jackson Laboratory (20, 22, 33). Because Cre protein was expressed in germ cells under the influence of the Meox2 promoter, Meox2Cre/+ Capn2+/− males were mated to Capn2flox/flox females to generate Capn2 cKO, Meox2Cre/+ Capn2−/flox offspring. Capn1 and Cast KO mice were as previously reported (3, 32).

Parental mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice (Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc.) over five generations. All animal experiments were carried out according to the RIKEN guidelines for animal experimentation.

Primary antibodies.

Antibodies were generated against mouse calpain-2 and calpain-1 domain IV and calpain small subunit 1 domain VI, which were purified using an ImmunoPure Melon Gel IgG purification kit (Pierce) from the sera of rabbits immunized with each recombinant protein expressed in Escherichia coli. The anti-calpain cleaved spectrin and calpastatin antibodies were as previously generated (32). Other antibodies were purchased as indicated: α-spectrin (clone AA6; Biohit), β-actin (clone AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich), PECAM1 (clone MEC 13.3; BD Pharmingen), cytokeratin (Z0622; Dako), CD34 (MEC14.7; Abcam), smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4; Sigma-Aldrich), caspase-3 cleaved cytokeratin (M30; Roche), cleaved caspase-3 (antibody 9661; Cell Signaling Technology), cleaved caspase-8 (antibody 3259; BioVision), and cleaved caspase-9 (antibody 9504; Cell Signaling Technology).

Western blot analysis.

Samples were homogenized in a 10-fold volume of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1+ Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The techniques used for SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, immunoreactions, and detection with the ECL Advance Western blotting Kit (GE Healthcare) were as previously described (32).

For the calpain activity assay, brains were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then homogenized in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mg of Pefabloc (Roche)/ml, along with 0.3 μM aprotinin for serine protease inhibition, 40 μg of bestatin/ml for aminopeptidase inhibition, 1 μM pepstatin for aspartic protease inhibition, 100 nM epoxomicin for proteasome inhibition, 1× PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and 1+ Triton X-100. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g, the supernatants were collected and incubated at 30°C after the addition of calcium chloride to a final concentration of 7 mM. The protein concentration of each sample was equalized by using BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce) to load equal amounts of samples.

Histochemistry.

Mouse embryos were fixed in 4+ paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) for 24 h at 4°C. The embryos were then photographed with an Olympus SZX5 stereomicroscope. For slice staining, fixed embryos were dehydrated using an ethanol and xylene series and then embedded in paraffin blocks. The paraffin blocks were sliced at 8 μm in the case of embryos and at 4 μm for placentas. The sections were then rehydrated and stained with Mayer's hematoxylin and eosin solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Immunohistochemical staining was performed by using a TSA-fluorescein system (Perkin-Elmer). To detect dead cells, an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche) was used with Hoechst 33342 counterstaining. Fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse E1000 fluorescence microscope or an Olympus FV300 confocal fluorescence microscope.

For whole-mount immunostaining, fetuses were dehydrated through a methanol series and bleached for 4 h in 5+ H2O2 in methanol. After rehydration, the fetuses were washed three times with 3+ skim milk–0.1+ Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS-MT), followed by incubation with anti-PECAM1 antibody diluted in PBS-MT. After five washes with PBS-MT, the fetuses were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rat IgG antibody (GE Healthcare), washed five times with PBS-MT, and developed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine. The reaction was stopped by rinsing the fetuses three times in PBS.

DNA laddering assay.

Placentas cleaned of maternal decidua were digested with proteinase K. After removal of the protein by phenol extraction, the DNAs were precipitated with sodium chloride-containing ethanol and dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA. Then, 10 μg of DNA and 200-bp ladder marker (TaKaRa) were loaded onto a 2+ agarose gel. The loaded DNA was quantified by determining the absorbance at 260 nm.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of conventional and conditional Capn2 knockout mice together with Capn1 Capn2 DKO mice.

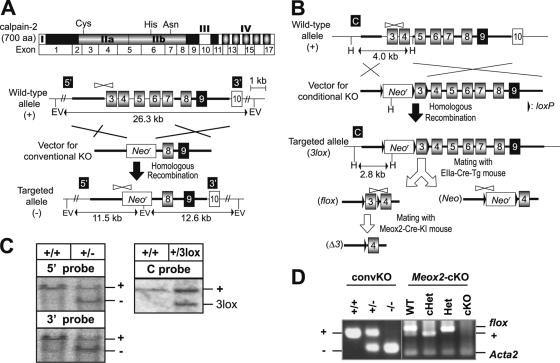

To generate conventional and conditional KO mice, we designed targeting vectors for homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells to disrupt the catalytic triad region in Capn2, i.e., exons 3 to 7 for the KO and exon 3 for the cKO (Fig. 1A and B). We created fetal-specific cKO mice using Cre recombinase knock-in mice under the control of the Meox2 promoter (33). Capn1 Capn2 double KO (DKO) mice were generated by crossbreeding Capn1 and the above Capn2 KO mice (3). We confirmed the success of the gene targeting by Southern blotting, genomic PCR and Western blotting (Fig. 1C and D, Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 1.

Gene targeting of Capn2 in mice. (A) Gene targeting for Capn2 KO. Schematic representations of the domain structure of calpain-2 protein, the exon structure, the wild-type allele (+), the targeting vector for conventional Capn2 KO, and the resultant targeted allele (−). Exons 3 to 7, including the catalytic triad (Cys105, His262, and Asn286 in protease domains IIa and IIb), were deleted in the targeted allele. The probe positions for Southern blotting (5′ and 3′ in black boxes), primer positions for Capn2 KO PCR genotyping (white arrowheads), the homologous region with targeting vector (bold line), restriction enzyme EcoRV sites (EV), neomycin resistance gene cassette (Neor), and the expected sizes in Southern blotting are indicated. (B) Gene targeting for generation of the Capn2 cKO and a second Capn2 KO line. Schematic representations of the wild-type allele, the targeting vector for cKO, the targeted allele (3lox), and alleles deleted of loxP-flanked regions in Cre-transgenic mice (flox, Neo, and Δ3). By mating with EIIa-Cre transgenic mice (22), the loxP-flanked neomycin resistance gene cassette and exon 3 were removed from the (3lox) allele to generate the Capn2 cKO line and another Capn2 KO line, respectively. Meox2-Cre knock-in (KI) mice were mainly used for Capn2 cKO analysis. The probe (C in black box) and restriction enzyme HindIII sites (H) for Southern blotting, primer positions for Capn2 cKO PCR genotyping (black arrow), and loxP sequences (black arrowhead) are indicated. For PCR genotyping for the second Capn2 KO line having the (Neo) allele, the same primers (see panel A) as for detection of the (−) allele were used. (C) Southern blotting to identify targeted embryonic stem cells. For the Capn2 KO, the 11.5- and 12.6-kb genomic fragments from the (−) allele were detected with the 5′ and 3′ probes (black boxes in panel A), respectively. For the Capn2 cKO, the 2.8-kb fragment from the (3lox) allele was detected with the C probe (black box in panel B). (D) PCR genotyping to identify mutant alleles. The left panel shows agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products from Capn2+/+, Capn2+/−, and Capn2−/− fetuses. The right panel shows agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products from Meox2+/+ Capn2+/flox (WT), Meox2Cre/+ Capn2+/flox (cHet), Meox2+/+ Capn2−/flox (Het), and Meox2Cre/+ Capn2−/flox (cKO) animals. In the cHet and cKO, the flox allele was deleted by Cre recombination.

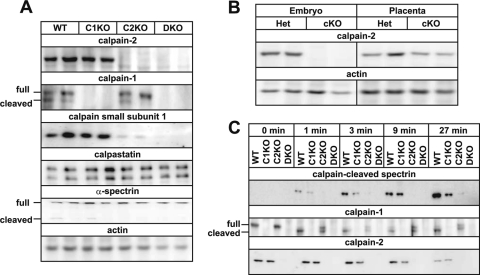

Fig. 2.

Protein expressions and calpain activity. (A) Western blotting for Capn2 conventional knockout fetuses. Capn1+/+ Capn2+/+ (WT), Capn1−/− Capn2+/+ (C1KO), Capn1+/+ Capn2−/− (C2KO), and Capn1−/− Capn2−/− (DKO) fetuses were analyzed at E10.5. Antibodies against calpain-2 domain IV, calpain-1 domain IV, calpain small subunit-1 domain VI, and calpastatin C terminus peptide were used. Using anti-calpain-1 antibody, the N-terminally autocleaved form was detected. (B) Western blotting for Capn2 cKO from fetuses and placentas. E13.5 placentas from Het (Meox2+/+ Capn2−/flox) and cKO (Meox2Cre/+ Capn2−/flox) mice were analyzed. (C) Calpain activation assay. Calcium ion was added to brain homogenates from 3-month-old Meox2+/+ Capn1+/+ Capn2+/+ (WT), Meox2+/+ Capn1−/− Capn2+/+ (C1KO), Meox2Cre/+ Capn1+/+ Capn2−/flox (C2cKO), and Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2−/flox (cDKO) mice and then incubated for 0, 1, 3, 9, or 27 min at 30°C. The cleavage form of calpain-1 but not calpain-2 was detected.

In the fetuses, calpain-2 appeared to be more abundant than calpain-1, with the calpain small subunit being almost nonexistent in Capn2 KO mice but not in Capn1 KO animals (Fig. 2A). Using an anti-α-spectrin antibody, a cleaved product of ∼150 kDa was slightly detected. These calpain cleavage products do not seem to be generated under physiological conditions. Figure 2C shows that the in vitro calcium-dependent proteolytic activity in adult brain homogenates was slightly reduced in Capn1 KO mice, almost fully abolished in Capn2 cKO mice and completely absent in conditional DKO mice (cDKO), (Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2−/flox), a finding consistent with the quantity of calpain small subunit-1 present (Fig. 2A). These observations indicate that calpain-1 and -2 are primarily responsible for calcium-dependent calpain activity in the adult brain, with calpain-2 playing the major role, although calpain-1 alone exhibited appreciable proteolytic activity. We also confirmed similar proteolytic properties in mutant fetuses (data not shown).

Lethality of calpain knockout mice at various embryonic stages.

Although the Capn2 heterozygotes grew and bred normally, we were not able to obtain neonatal homozygous Capn2 KO mice. To estimate the lethal stage, embryos from intercrossed heterozygous parental mice were collected and genotyped at different embryonic days (Table 1). Stereomicroscopic observations indicated failure of peripheral vessels in the limb and head regions from E15.5 in the Capn2 KO mice (Fig. 3A d to f). Another line of Capn2 KO mice generated using a different targeting vector exhibited an identical phenotype (Fig. 4). Interestingly, this deteriorative phenotype was accelerated in DKO mice (Fig. 3Aj to l), with the fetuses dying ∼3 days earlier (Table 2). This suggested additive nature of Capn1 and Capn2 deficiency in vivo, although Capn1 deficiency alone appeared essentially harmless (3).

Table 1.

Genotypes of embryos from Capn2+/− intercrosses

| Age (embryonic day) | No. of embryos with genotypea: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |

| E12.5 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| E13.5 | 30 | 42 | 22 |

| E14.5 | 20 | 36 | 16 |

| E15.5 | 30 | 75 | 2* |

| E16.5 | 25 | 38 | 2* |

| Adult | 68 | 146 | 0* |

*, P < 0.001 (chi-square test). The embryos at E12.5, E13.5, E14.5, and E16.5 were obtained from 2, 13, 10, 8, and 4 crosses, respectively.

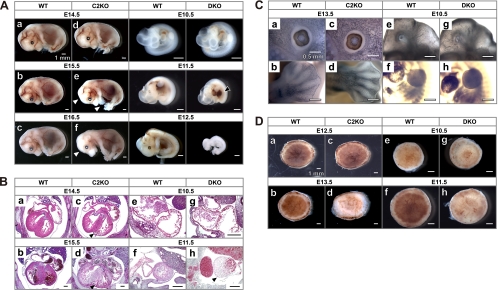

Fig. 3.

Capn2 knockout and Capn1 Capn2 DKO embryos. (A) Appearance of mutant embryos. Wild-type (WT; a to c) and Capn2−/− embryos (C2KO; d to f) at E14.5 to E16.5 and wild-type (WT; g to i) and Capn1−/− Capn2−/− embryos (DKO; j to l) at E10.5 to E12.5 were photographed with a stereomicroscope. Peripheral vessels were diminished in six of 12 and all seven C2KO fetuses at E15.5 and E16.5, respectively (white arrowhead in panels e and f). Hepatic hemorrhages were detected in 6 of 11 DKO fetuses (black arrowhead in panel k). At E12.5 the all 14 DKO fetuses were absorbed (l). Tails were used for PCR genotyping. (B) Cardiac morphology. Transverse sections of WT (a and b) and C2KO (c and d) at E14.5 and E15.5 and sagittal sections of WT (e and f) and DKO (g and h) at E10.5 and E11.5 were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. The ventricular walls in C2KO and DKO were thinner than those of the WT (black arrowheads in panels c, d, and h). Cardiac abnormality was detected one of three and all three C2KO embryos at E14.5 and E15.5, respectively, and all three DKO embryos at E11.5. (C) Whole-mount immunostaining with anti-PECAM1 antibody. The eyes (a and c) and forelimbs (b and d) of the WT and C2KO at E13.5 and the head (e and g) and trunk (f and h) of the WT and DKO at E10.5 were visualized with diaminobenzidine after horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody staining. We could not detected significant abnormality in all three C2KO and DKO embryos at this stage. (D) Appearance of placentas. Fetal sides of WT (a, b, e, and f), C2KO (c and d), and DKO (g and h) placentas were photographed with a stereomicroscope. Blood flow in the labyrinth was decreased in the C2KO and the DKO (d and h). We detected pale placentas (d and h) in four of 10 C2KO mice at E13.5 and all 10 DKO mice at E11.5.

Fig. 4.

Phenotype of a second Capn2 knockout mouse generated using a different targeting vector. (A) Stereomicroscopy of wild-type (WT; a and b) and second Capn2 KO (Neo/Neo; c and d) (Fig. 1B) fetuses and placentas. (B) Hematoxylin-eosin, in situ TUNEL, and Hoechst 33342 staining of wild-type (WT; a to c) and second Capn2 KO (Neo/Neo; d to f) placentas.

Table 2.

Genotypes of embryos from Capn1−/− Capn2+/− intercrosses

| Age (embryonic day) | No. of embryos with Capn2 genotypea: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | |

| E9.5 | 11 | 19 | 13 |

| E10.5 | 17 | 36 | 20 |

| E11.5 | 28 | 49 | 15 |

| E12.5 | 17 | 32 | 0* |

| E13.5 | 15 | 26 | 0* |

*, P < 0.001 (chi-square test). The embryos at E9.5, E10.5, E11.5, E12.5, and E13.5 were obtained from 7, 9, 12, 6, and 7 crosses, respectively.

Because peripheral vessel failure could be caused by cardiovascular abnormality, we examined the cardiac region of the KO mice by hematoxylin-eosin staining. This analysis revealed cardiac disruption in the late but not the early stage of embryonic lethality. No significant abnormality, such as pericardial effusion or atrial enlargement (Fig. 3B), which is generally associated with defects in cardiac development (15, 38), was observed. Whole-mount immunostaining with anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM1) antibody detected no difference in vasculogenesis or angiogenesis between the control and mutant mice (Fig. 3C). Examination of other tissues revealed that the placental abnormalities arose prior to embryonic lethality (Fig. 3D); we observed paling of the placentas at E13.5 and at E11.5 in single Capn2 (Fig. 3Dd) and DKO (Fig. 3Dh) mice, respectively.

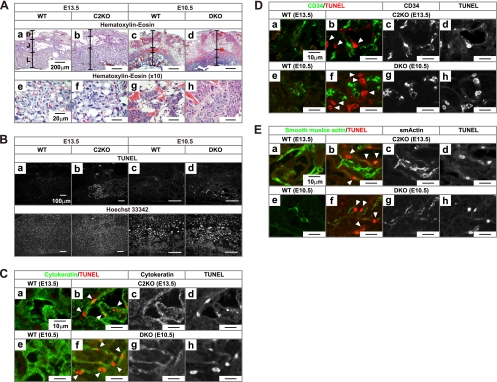

Cell death in the placental labyrinth.

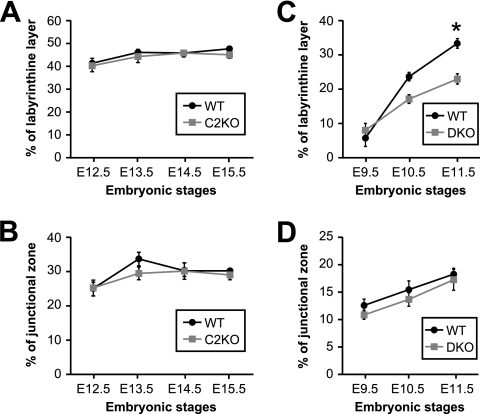

Hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed normal development of the labyrinth and no abnormalities in the spongiotrophoblasts and trophoblast giant cells of the Capn2 KO labyrinth but reduced development in the DKO labyrinth (Fig. 5A and Fig. 6C). In situ terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining detected cell death with DNA fragmentation selectively in the mutant labyrinthine region (Fig. 5B). The TUNEL-positive cells were identified as trophoblasts which could be immunostained with anticytokeratin antibody (Fig. 5C). We could not detect any developmental abnormality in either the endothelium or the smooth muscle stained with anti-CD34 and smooth muscle actin antibodies, respectively (Fig. 5D and E).

Fig. 5.

Cell death in placental trophoblasts. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining of placental slices. (a to d) Three-layer structure formed by decidua (D), junctional zone (J; containing spongiotrophoblasts and giant cells), and labyrinth (L) is indicated. No growth abnormality of junctional zone were detected in the C2KO (b) or the DKO (d) (see Fig. 6) mice. Panels e to h are 10-fold-magnified images of the labyrinthine region. Severe developmental abnormalities were detected in the DKO (h) but not in the C2KO (f) mice. (B) In situ TUNEL and Hoechst 33342 double staining. TUNEL signals were detected specifically in the labyrinthine region of the C2KO and the DKO placentas (b and d). TUNEL-positive cells in the labyrinth were detected in 3 of 10 and 7 of 10 C2KO placentas at E13.5 and E14.5 and in 5 of 10 and all 10 DKO placentas at E10.5 and E11.5, respectively. (C) Double staining with in situ TUNEL and anticytokeratin antibody. TUNEL-positive cells in the C2KO and DKO mice (red in panels b and f, arrowheads) were costained with anticytokeratin antibody, a trophoblast marker (green). The images were acquired by confocal fluorescence microscopy. (D) Double staining with in situ TUNEL and anti-CD34 antibody. TUNEL-positive cells in the C2KO and DKO (red in panels b and f, arrowheads) did not costain with anti-CD34 antibody, an endothelial marker (green). (E) Double staining with in situ TUNEL and anti-smooth muscle actin antibody. TUNEL-positive cells in the C2KO and DKO (red in panels b and f, arrowheads) did not costain with anti-smooth muscle actin antibody, a blood vessel muscle marker (green).

Fig. 6.

Proportion of labyrinthine and junctional zones in Capn2−/− and Capn1−/− Capn2−/− placentas. (A and B) Proportion of labyrinthine and junctional zones of wild-type (WT) and Capn2−/− (C2KO) placentas. (C and D) Proportion of labyrinthine and junctional zones of WT and Capn1−/− Capn2−/− (DKO) placentas. Proportion of labyrinthine and junctional zones were quantified by measuring the length of each layer. Error bars indicate ± the standard errors of the mean. *, P < 0.01 (Tukey-Kramer test, n = 8 to 10 for each genotype and developmental stage).

Apoptosis-like cell death accompanying hyperactivation of caspases and DNA laddering.

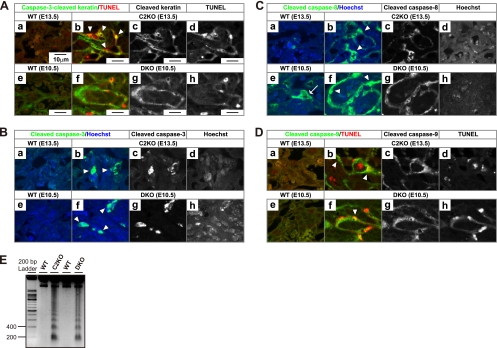

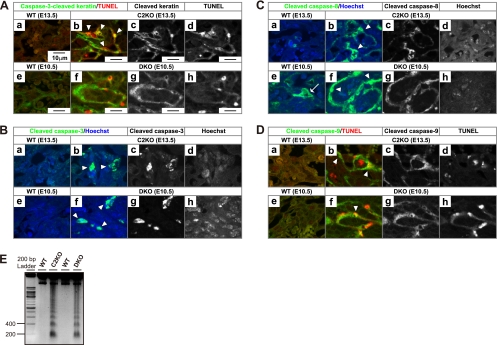

In an effort to identify the mechanism of cell death, we investigated the activation of caspases, well-known executors of apoptosis. Caspase-3, a death effector, was activated in Capn2 KO and DKO trophoblasts (Fig. 7A and B). The activation of initiator caspases, caspase-8 and -9, remained in larger trophoblasts in both mutants, whereas wild-type labyrinth showed marginal activity (Fig. 7C and D). We also detected DNA fragmentation with a laddering pattern, a phenomenon that is typical of apoptosis (Fig. 7E). These results indicate that the nature of the cell death in the Capn2 KO and DKO mice can be classified as apoptosis involving caspase activation and DNA laddering.

Fig. 7.

Immunohistochemical study for caspase activation and apoptotic DNA fragmentation. (A) Double staining with anti-caspase-3-cleaved cytokeratin antibody and in situ TUNEL. Cells costained for anti-caspase-3-cleaved cytokeratin (green) and TUNEL (red) are indicated by the arrowheads (b and f). Panels a, b, e, and f represent merged color images. Panels c, d, g, and h are corresponding gray-scale images. The images were acquired by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The caspase-3-cleaved cytokeratin-positive cells in labyrinth were increased in 5 of 10 and 5 of 10 C2KO placentas at E13.5 and E14.5 and in 6 of 10 and all 10 DKO placentas at E10.5 and E11.5, respectively. (B) Double staining with anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody and Hoechst 33342. Anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody-positive cells (green) are indicated by the arrowheads (b and f). The cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in labyrinth were increased in 5 of 10 and 4 of 10 C2KO placentas at E13.5 and E14.5 and in 3 of 10 and 9 of 10 DKO placentas at E10.5 and E11.5, respectively. (C) Double staining with anti-cleaved caspase-8 antibody and Hoechst 33342. Anti-cleaved caspase-8 antibody-positive cells (green) are indicated by the arrowheads (b and f). The arrow indicates the caspase-8 activation in an undifferentiated WT trophoblast (e). The cleaved caspase-8-positive cells in labyrinth were increased in 6 of 10 and 5 of 10 C2KO placentas at E13.5 and E14.5 and in 4 of 10 and all 10 DKO placentas at E10.5 and E11.5, respectively. (D) Double staining with anti-cleaved caspase-9 and in situ TUNEL cells costained for anti-cleaved caspase-9 (green) and TUNEL (red) are indicated by arrowheads (b and f). The cleaved caspase-9-positive cells in labyrinth were increased in 7 of 10 C2KO placentas at both E13.5 and E14.5 and in 6 of 10 and all 10 DKO placentas at E10.5 and E11.5, respectively. (E) Agarose gel electrophoresis of labyrinthine DNA from the WT and C2KO at E14.5 and from the WT and DKO at E12.5 for characterization of DNA fragmentation. The image stained with ethidium bromide under UV light was inverted.

Genetic rescue of the embryo in fetus-specific conditional calpain knockout mice and in Capn2 Cast DKO mice.

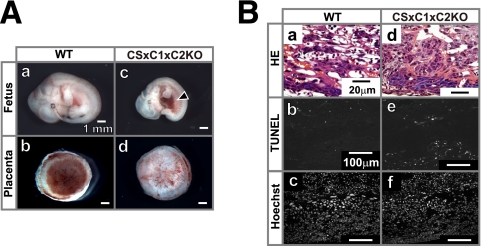

To confirm that the observed placental dysfunction leads to fetal lethality, we generated Capn2 cKO mice carrying Meox2 promoter-driven Cre, which only express Capn2 in extraembryonic tissues, and cDKO mice (Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2−/flox). Nearly half of the Capn2 cKO and cDKO mice survived to adulthood (Table 3). This observation indicates that the expression of calpain in the placenta is essential for normal development of the embryo. We also generated DKO mice deficient in Capn2 and the calpastatin gene, Cast, to examine whether the presence or absence of this calpain inhibitor protein plays a role in embryogenesis. The Capn2 Cast DKO mice also appeared to lack any significant abnormality, although the probability of survival was ca. 50+ lower than expected (Table 2C). In contrast, a deficiency in Calpn1 Capn2 Cast in triple-KO mice resulted in embryonic lethality at E11.5 (Table 4 and Fig. 8). The outcomes of multiple-crossbreeding among the Capn1, Capn2, and Cast KO mice are summarized in Table 5.

Table 3.

Genotypes of Meox2 Capn2 and Capn1 Capn2 conditional knockout embryos

| Genotype | No. of embryosa: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mating 1 | Mating 2 | |

| WT | 27 | 27 |

| Het | 16 | 17 |

| cHet | 36 | 27 |

| cKO | 13 | 14 |

Mating 1: Meox2Cre/+ Capn2+/− and Capn2flox/flox. For mating 1, WT, Het, cHet, and cKO denote Meox2+/+ Capn2+/flox, Meox2+/+ Capn2−/flox, Meox2Cre/+ Capn2+/flox, and Meox2Cre/+ Capn2−/flox, respectively. The mice were obtained from 15 crosses. Mating 2: Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2+/− and Capn1−/− Capn2flox/flox. For mating 2, WT, Het, cHet, and cKO denote Meox2+/+ Capn1−/− Capn2+/flox, Meox2+/+ Capn1−/− Capn2−/flox, Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2+/flox, and Meox2Cre/+ Capn1−/− Capn2−/flox, respectively. The mice were obtained from 16 crosses.

Table 4.

Genotypes of Capn1 Capn2 and Cast Capn1 Capn2 knockout mice and Tek Capn1 Capn2 conditional knockout mice

| Genotype (1-month-old mice) | Cross (no. of crosses) | No. of mice with genotype: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | ||

| Capn2 | Cast−/−Capn2+/− (15) | 37 | 52 | 14 |

| Cast−/−Capn1−/−Capn2+/− (6) | 8 | 26 | 0a | |

| Creb | Tek-Cre+/−Capn1−/−Capn2flox/flox and Capn1−/−Capn2flox/flox(13) | 41 | 42 | |

P < 0.005 (chi-square test).

The Tek-Cre+/− Capn1−/− Capn2flox/flox mice did not show any significant abnormality for at least 1 year.

Fig. 8.

Phenotype of the Cast−/− Capn1−/− Capn2−/− embryo. (A) Stereomicroscopy of wild-type (WT [a and b]) and Cast−/− Capn1−/− Capn2−/− (CS×C1×C2KO [c and d]) fetuses and placentas at E11.5. Hemorrhages were detected in the trunk region of the CS×C1×C2KO (arrowhead in panel c). (B) Hematoxylin-eosin, in situ TUNEL, and Hoechst 33342 staining of WT (a to c) and second CS×C1×C2KO (d to f) placentas.

Table 5.

Summary of the fetal phenotypes of calpain-calpastatin mutants

| Genotypea |

Phenotype | Source or reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capn1 | Capn2 | Cast | ||

| WT | WT | WT | Normal | |

| KO | WT | WT | Normal | 3 |

| WT | KO | WT | Lethal at E15.5 | Fig. 3Ae |

| WT | WT | KO | Normal | 32 |

| KO | KO | WT | Lethal at E11.5 | Fig. 3Ak |

| KO | WT | KO | Normal | Data not shown |

| WT | KO | KO | Normal | Table 4 |

| KO | KO | KO | Lethal at E11.5 | Fig. 8 |

WT, wild type; KO, knockout.

DISCUSSION

Our experimental results indicate that the calpain-calpastatin system plays an essential role in embryogenesis by regulating the survival of placental trophoblasts. Of the two calpain isozymes, calpain-2 appears to be the quantitatively predominant species in the embryo. Consistent with this, the phenotype that arises from calpain-2 deficiency is embryonic lethal, whereas that resulting from calpain-1 deficiency is essentially normal.

Two independent lines of Capn2 KO mice that we generated using distinct targeting vectors consistently exhibited embryonic lethality at E15, in contrast to the previous report that Capn2 KO embryos died at E2.5, prior to implantation (7). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but the extremely early death of the Capn2 KO embryos in the latter case appears to be unnatural for two reasons. First, Capns1 KO embryos which lack both calpain-1 and -2 die at E10.5, after implantation (2) and, second, Capn1 Capn2 DKO mice die at E11.5 in a manner similar to Capns1 KO mice. Consistent with the findings of Arthur et al. (2), our observations also indicate that the catalytic and regulatory subunits of calpain are both required for heterodimeric stability. Although more than 10 calpain isoforms have been identified in mammals (29), calpain-1 and -2 appear to account for essentially all of the calpain activity in the embryonic brain.

Although it is evident that calpain-2 plays a more important role than calpain-1 and calpastatin in embryogenesis, the latter two do influence the former. First, an additional lack of calpain-1 worsens the developmental phenotype of calpain-2 KO embryos. This additive effect of calpain-1 and -2 activities suggests that these isoforms share at least some functional redundancy, despite the difference in their in vitro calcium sensitivity. Second, it is notable that calpastatin deficiency partially rescued the lethal phenotype caused by calpain-2 deficiency. This is presumably because suppression of calpain-1 activity by calpastatin was removed in Capn2 and Cast DKO embryos; consistent with this interpretation, triple calpain-1, calpain-2, and calpastatin deficiency resulted in the same embryonic lethality as that observed in the Capn1 Capn2 DKO embryos.

These observations have profound implications for our understanding of the in vivo effect of the calpain-calpastatin system. First, both calpain-1 and -2 can be activated under physiological conditions in which calcium concentrations are generally in the submicromolar range, although they require micro- and millimolar concentrations of calcium, respectively, to exert an effect in vitro. Second, because these isozymes appear to share at least some functional redundancy, they are also likely to possess similar substrate specificity in vivo. Third, although calpastatin is known to bind and inhibit to calpain-1 and -2 in a calcium-dependent manner in vitro (13, 23, 37), the calpain-calpastatin interaction takes place under physiological conditions and, finally, autolysis of the regulatory domain in calpain-2 is unlikely to play a major role in the activation process because the catalytic subunit of calpain-2, unlike that of calpain-1, does not undergo autolysis for its activation (27).

The downstream events that follow calpain-2 activation appear to involve inactivation of caspase-3, -8, and -9. Caspase-8 is known to contribute to the fusion of cytotrophoblasts into syncytiotrophoblasts without cell death (4). However, calpain appears not to mediate placental trophoblast fusion, calpain inhibitors can suppress hCGβ (human chorionic gonadotropin beta subunit) secretion in placental culture (10). On the contrary, upregulation of calpain-1 in human decidua was suggested the relationship with recurrent miscarriage (21). Considering these results, control of calpain activation seems to be a key for proper embryonic development. To elucidate these phenomena, we should test reproductive capability and placental cell death using parental Meox2 Capn2 cKO mice.

Several reports indicate that abnormalities in placental development may cause defects in the embryonic cardiovascular system (1, 12, 31). We have provided more conclusive evidence regarding the essential role of calpain in placental development using cKO and cDKO mice, in which calpain-2 expression is limited in the extraembryonic region by the Meox2-Cre transgene. Another cDKO mouse line under the control of Tek-Cre endothelium-specific deleter (20) survived to adulthood without significant abnormality (Table. 2E). This observation indicates that the cardiovascular phenotype was not caused by calpain deficiency in the blood vessels, of which endothelial cells are a major constituent. However, there is a possibility that other tissues other than those of placental trophoblasts are involved in embryonic lethality in Meox2-Cre induced cKO embryos because they still showed partial lethality.

These findings also have obstetric implications, given that labyrinthine trophoblasts play a critical role in the exchange of oxygen and nutrients between the maternal and embryonic circulations (25). Indeed, preeclampsia, a disease of human pregnancy, seems to be associated with cell death in the placenta (8, 19, 30). Despite the fact that a substantial number of human pregnancies fail as spontaneous abortions after implantation, the underlying mechanisms remain undetermined. The present study points to the possibility that calpain can act as a target for the prevention and treatment of preeclampsia and other maternal-embryonic diseases that accompany placental cell death.

Finally, there are still a number of questions that remain to be addressed. First, nothing is known about the postembryonic functions of calpain. Use of Cre-Tg mice under the control of various promoters should provide some insight regarding this. Second, the in vivo mechanism of calpain-1 and -2 activation has not yet been fully elucidated. The generation of multiple mutant mice deficient in or overexpressing components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase and calpain signaling systems may provide us with some additional clues. Third, we know nothing about the functional difference between calpain-1 and -2, although the present study indicates that these isozymes share at least some redundancy. Fourth, we do not yet have solely calpain-specific cell-permeable inhibitors, let alone an inhibitor that can distinguish between calpain-1 and -2. Such inhibitors would be extremely beneficial for both basic and clinical studies of the effects of calpain. Again, mutant mice and cells that lack or overexpress calpain-calpastatin system components would provide useful tools for screening inhibitors and possibly activators, with the determination of the three-dimensional structure of calpain (18), thereby generating an appreciable momentum for such efforts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Mika Tanaka (RIKEN), Satoshi Tanaka (Tokyo University), and Yasuhiko Ozaki (Nagoya City University) for placental analysis, as well as Issei Komuro and Hiroshi Akazawa of Osaka University for cardiac diagnosis of mouse embryos. We also thank Masaki Kumai, Masanobu Kawatana, and Mayu Kawasaki for technical assistance.

This study was supported by research grants from the RIKEN Brain Science Institute and by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of the Japanese Government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 July 2011.

The authors have paid a fee to allow immediate free access to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams R. H., et al. 2000. Essential role of p38α MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Mol. Cell 6:109–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arthur J. S., Elce J. S., Hegadorn C., Williams K., Greer P. A. 2000. Disruption of the murine calpain small subunit gene, Capn4: calpain is essential for embryonic development but not for cell growth and division. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:4474–4481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azam M., et al. 2001. Disruption of the mouse μ-calpain gene reveals an essential role in platelet function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2213–2220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Black S., et al. 2004. Syncytial fusion of human trophoblast depends on caspase 8. Cell Death Differ. 11:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carafoli E., Molinari M. 1998. Calpain: a protease in search of a function? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Croall D. E., DeMartino G. N. 1991. Calcium-activated neutral protease (calpain) system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev. 71:813–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dutt P., et al. 2006. m-Calpain is required for preimplantation embryonic development in mice. BMC Dev. Biol. 6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feinberg B. B. 2006. Preeclampsia: the death of Goliath. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 55:84–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Franco S. J., Huttenlocher A. 2005. Regulating cell migration: calpains make the cut. J. Cell Sci. 118:3829–3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gauster M., et al. 2010. Caspases rather than calpains mediate remodeling of the fodrin skeleton during human placental trophoblast fusion. Cell Death Differ. 17:336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glading A., Chang P., Lauffenburger D. A., Wells A. 2001. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation of calpain is required for fibroblast motility and occurs via an ERK/MAP kinase signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2390–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goll D. E., Thompson V. F., Li H., Wei W., Cong J. 2003. The calpain system. Physiol. Rev. 83:731–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanna R. A., Campbell R. L., Davies P. L. 2008. Calcium-bound structure of calpain and its mechanism of inhibition by calpastatin. Nature 456:409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hatano N., Mori Y., Oh-hora, et al. 2003. Essential role for ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental development. Genes Cells 8:847–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hein L., et al. 1997. Overexpression of angiotensin AT1 receptor transgene in the mouse myocardium produces a lethal phenotype associated with myocyte hyperplasia and heart block. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:6391–6396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hernandez A. A., Roush W. R. 2002. Recent advances in the synthesis, design and selection of cysteine protease inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 6:459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higuchi M., et al. 2005. Distinct mechanistic roles of calpain and caspase activation in neurodegeneration as revealed in mice overexpressing their specific inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 280:15229–15237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hosfield C. M., Elce J. S., Davies P. L., Jia Z. 1999. Crystal structure of calpain reveals the structural basis for Ca2+-dependent protease activity and a novel mode of enzyme activation. EMBO J. 18:6880–6889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jurisicova A., Detmar J., Caniggia I. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of trophoblast survival: from implantation to birth. Birth Defects Res. 75:262–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koni P. A., et al. 2001. Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow. J. Exp. Med. 93:741–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kumagai K., et al. 2008. Role of mu-calpain in human decidua for recurrent miscarriage. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 59:339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lakso M., et al. 1996. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:5860–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moldoveanu T., Gehring K., Green D. R. 2008. Concerted multi-pronged attack by calpastatin to occlude the catalytic cleft of heterodimeric calpains. Nature 456:404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakajima R., et al. 2008. Comprehensive behavioral phenotyping of calpastatin-knockout mice. Mol. Brain. 1:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rossant J., Cross J. C. 2001. Placental development: lessons from mouse mutants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2:538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saido T. C., Sorimachi H., Suzuki K. 1994. Calpain: new perspectives in molecular diversity and physiological-pathological involvement. FASEB J. 8:814–822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saido T. C., et al. 1994. Distinct kinetics of subunit autolysis in mammalian m-calpain activation. FEBS Lett. 346:263–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shiraha H., Glading A., Chou J., Jia Z., Wells A. 2002. Activation of m-calpain (calpain II) by epidermal growth factor is limited by protein kinase A phosphorylation of m-calpain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2716–2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sorimachi H., Suzuki K. 2001. The structure of calpain. J. Biochem. 129:653–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Straszewski-Chavez S. L., Abrahams V. M., Mor G. 2005. The role of apoptosis in the regulation of trophoblast survival and differentiation during pregnancy. Endocrinol. Rev. 26:877–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzuki K., Sorimachi H. 1998. A novel aspect of calpain activation. FEBS Lett. 433:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takano J., et al. 2005. Calpain mediates excitotoxic DNA fragmentation via mitochondrial pathways in adult brains: evidence from calpastatin mutant mice. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16175–16184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tallquist M. D., Soriano P. 2000. Epiblast-restricted Cre expression in MORE mice: a tool to distinguish embryonic versus extra-embryonic gene function. Genesis 26:113–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang K. K. W., Yuen P. W. 1999. Calpain: pharmacology and toxicology of calcium-dependent protease. Taylor and Francis, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu L., et al. 2003. Extra-embryonic function of Rb is essential for embryonic development and viability. Nature 421:942–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yamada M., et al. 2009. Inhibition of calpain increases LIS1 expression and partially rescues in vivo phenotypes in a mouse model of lissencephaly. Nat. Med. 15:1202–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang H. Q., Ma H., Takano E., Hatanaka M., Maki M. 1994. Analysis of calcium-dependent interaction between amino-terminal conserved region of calpastatin functional domain and calmodulin-like domain of μ-calpain large subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18977–18984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yao T. P., et al. 1998. Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300. Cell 93:361–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zatz M., Starling A. 2005. Calpains and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:2413–2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]