Abstract

The growth and maturation of bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) from precursors are regulated by coordinated signals from multiple cytokine receptors, including KIT. While studies conducted using mutant forms of these receptors lacking the binding sites for Src family kinases (SFKs) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) suggest a role for these signaling molecules in regulating growth and survival, how complete loss of these molecules in early BMMC progenitors (MCps) impacts maturation and growth during all phases of mast cell development is not fully understood. We show that the Lyn SFK and the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K play opposing roles in regulating the growth and maturation of BMMCs in part by regulating the level of PI3K. Loss of Lyn in BMMCs results in elevated PI3K activity and hyperactivation of AKT, which accelerates the rate of BMMC maturation due in part to impaired binding and phosphorylation of SHIP via Lyn's unique domain. In the absence of Lyn's unique domain, BMMCs behave in a manner similar to that of Lyn- or SHIP-deficient BMMCs. Importantly, loss of p85α in Lyn-deficient BMMCs not only represses the hyperproliferation associated with the loss of Lyn but also represses their accelerated maturation. The accelerated maturation of BMMCs due to loss of Lyn is associated with increased expression of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf), which is repressed in MCps deficient in the expression of both Lyn and p85α relative to controls. Our results demonstrate a crucial interplay of Lyn, SHIP, and p85α in regulating the normal growth and maturation of BMMCs, in part by regulating the activation of AKT and the expression of Mitf.

INTRODUCTION

Mast cells play an essential role in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses (7, 8, 18, 29). Mast cell progenitors (MCps) are present in adult bone marrow (BM) (17, 20). These progenitors seed the connective and mucosal tissues, where they reside throughout adult life and mature into definitive connective and mucosal mast cells (3, 9), distinguished by the expression of specific proteases (41). The cellular mechanisms involved in regulating mast cell differentiation have been best characterized in vitro in liquid cultures stimulated with cytokines, including interleukin-3 (IL-3) and stem cell factor (SCF), the ligand for KIT (5, 32). Under these conditions, low-density mononuclear cells from BM give rise to BM-derived mast cells (BMMC), which phenotypically and functionally resemble mast cell precursors purified from the mucosal tissues of adult animals. While significant progress has been made in characterizing the cellular events leading up to mast cell maturation, the basic intracellular signaling cues required for the differentiation, growth, and survival of these cells remain poorly understood. Importantly, how positive and negative signals induced in response to IL-3 and SCF during the different phases of mast cell maturation are integrated to regulate mast cell development is not fully understood.

Stimulation of the IL-3 receptor activates the Lyn SFK (1, 44). Lyn physically associates with the β common chain of the IL-3 receptor (25). Studies involving knockdown of Lyn in hematopoietic cells have shown that Lyn positively regulates cytokine-mediated survival (36, 47, 49). Likewise, KIT stimulation by SCF induces the activation of Lyn and knockdown and pharmacologic inhibitor studies have revealed that Lyn positively regulates KIT signaling (26). Lyn binds KIT via tyrosine 567, which is located in the juxtamembrane region of the receptor (46). Although tyrosine 567 is an essential site for regulating KIT-induced functions, other members of the SFK family also bind this site and are expressed in mast cells (24, 43). Therefore, it is unclear if the defects associated with the loss of this docking site can be attributed to one specific SFK. Adding to the complexity of the situation are studies demonstrating conflicting results with respect to the role of Lyn in mast cell functions. Some studies have found no defects in mast cells as a result of Lyn deficiency, others have found enhanced functions, and yet others have reported reduced functions (11, 16, 31, 33, 34). Thus, the role of the Lyn SFK in mast cell maturation and growth remains largely controversial.

A vast majority of the studies involving cytokine receptor signaling have focused on the mechanism(s) by which receptors and ligands interact and exert positive cellular outcomes. While it is well appreciated that the cytokine receptor interaction is restricted in both magnitude and duration, it is not clear, however, how cytokine receptors integrate both positive and negative signals in a cell, particularly during the different phases of maturation, such as that observed in BMMCs. To this end, Src homology 2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP) has been implicated in the negative regulation of multiple hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell functions, including mast cell functions (4, 10, 12–14, 27).

While studies thus far have clearly suggested a role for SHIP and the p85α regulatory subunit of class IA phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) in regulating some aspects of mast cell function(s) (6, 12, 13), a fundamental question that has emerged from studies of SHIP−/− mast cells is the mechanism(s) by which SHIPs function is regulated in mast cells and how cytokine-induced signals in mast cells integrate to positively and negatively impact growth, as well as mast cell maturation. Utilizing biochemical, molecular, and genetic approaches, we show that the Lyn Src family kinase (SFK) plays an essential role in regulating the phosphorylation of SHIP in mast cells in response to cytokine stimulation. We have identified the functional domain of Lyn necessary for the regulation of SHIP phosphorylation and binding in response to cytokine stimulation in BMMCs. Furthermore, several Src and PI3K family members are expressed in mast cells (6, 28, 35) and the individual contributions of these members to cytokine-induced growth and development are poorly understood. We show that the Lyn SFK and the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K play opposing roles in regulating mast cell development and function. We further show that cytokine-induced hyperresponsiveness, including enhanced maturation due to Lyn deficiency or Lyn haploinsufficiency in mast cell progenitors, is partly mediated via the hyperactivation of class IA PI3K. More importantly, downstream from PI3K, the accelerated maturation of MCps due to Lyn deficiency is mediated in part via the enhanced expression of the “master regulator” of mast cell differentiation, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf). Our results demonstrate that the Lyn-SHIP axis negatively regulates mast cell growth and maturation in part by regulating the activation of PI3K/AKT via the p85α regulatory subunit of PI3K.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, cytokines, and antibodies.

The p85α−/−, SHIP−/−, and Lyn−/− mice (all in a C57BL/6 genetic background) used in this study have been previously described (12, 13, 30). These mice were genotyped on the basis of previously published methods (12, 13, 30). All mice were used at 6 to 10 weeks of age. Mice deficient in p85α and Lyn were generated by crossing p85α+/− and Lyn+/− mice. All mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Indiana University Laboratory Animal Research Center (Indianapolis, IN).

IL-3 and SCF were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Anti-phospho-AKT, ERK, Stat5, and JNK antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverley, MA). Antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) tag and anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibodies were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-Mitf antibody was generated by Clifford Takemoto (23). Anti-KIT antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-KIT antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC) and anti-Fcε receptor I (anti-FcεRI) antibody conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA).

Generation of BMMCs and assessment of differentiation.

BMMCs were generated from the femurs, tibias, and iliac crests of wild-type (WT) and various mutant mice that were 6 to 10 weeks of age. BM cells were flushed using a syringe-needle and Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Low-density BM cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque 1083 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Next, the cells were cultured in IMDM-10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10 ng/ml IL-3 for 3 to 4 weeks and used in biochemical and functional studies.

Differentiation of BMMCs was monitored on a weekly basis by collecting and washing cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were subsequently blocked with PBS containing 10% rat serum and 0.2% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at 4°C and stained with a combination of APC-conjugated anti-KIT and PE-conjugated anti-FcεRI antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. Next, cells were washed and analyzed using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data were analyzed using CellQuest (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or Flow Plus (Accuri Cytometers, Ann Arbor, MI). In addition to flow cytometric analysis, maturation of BMMCs was also assessed by conducting cytospins. BMMCs were harvested after 1, 2, 3, or 4 weeks and washed with sterile PBS. Cells were resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml, and 100 μl of these cells was loaded into each slot and centrifuged at 800 rpm for 5 min. Slides were stained using Giemsa stain, and photomicrographs were taken at a magnification of ×400 using DM4000B equipment from Leica Microsystems (Bannockburn, IL).

Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blot (WB) analysis.

BMMCs expressing various mutant constructs were starved overnight in the absence of serum and growth factors. Cells were stimulated with 500 ng/ml SCF for 2 min. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to protein estimation. Two micrograms of anti-SHIP monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) was added to 500 μg of cell lysate. The protein-antibody complexes were incubated overnight at 4°C, and immunoprecipitates were recovered by incubation with protein A-G–Sepharose beads for 4 h at 4°C (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Beads were washed four times in lysis buffer and eluted by boiling for 5 min in 2× Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Immunoprecipitated samples were subjected to WB analysis. Briefly, an equal amount of protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and separated proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline–Tween 20. WB analysis was performed using the indicated antibodies. The Supersignal West Dura extended-duration detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to visualize protein signals.

PI3K activity assay.

Cells were lysed in PI3K lysis buffer (137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate containing 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 50 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.5 mM leupeptin). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Ten to fifty micrograms of protein was subjected to IP using an anti-p85α antibody (Upstate) with constant rocking for 4 h at 4°C. A protein A-G mixture was used to collect the immune complex. The immune complex was washed twice with lysis buffer and once with kinase buffer (125 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS; pH 7], 25 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA). The pellet was suspended in 5 μl of kinase buffer consisting of 10 μl of sonicated phosphatidylinositol and 4 μl of MgCl2. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 μCi [32P]ATP (Perkin-Elmer). After incubation for 10 min at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 105 μl of 1 N HCl, followed by 160 μl of chloroform-methanol (1:1, vol/vol). The samples were vortexed vigorously, and the organic phase (25 μl) was analyzed for phosphatidylinositol triphosphate (PIP3) by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using an oxalated (oxalate with 1% potassium oxalate in methanol-water [40:60]) silica gel 60 plate (Fisher). The lipids were separated using 1 M acetic acid and 2-proponol as the solvent system in a closed glass chamber (35:65, vol/vol). The TLC plates were subjected to autoradiography by exposure to Kodak BioMax film.

Construction and cloning of WT Lyn and a version of Lyn with the unique domain deleted.

Whole spleen tissue was used as a source of total RNA for the synthesis of cDNA encoding Lyn. Total RNA was extracted using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) by following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 1 ml of TRI Reagent was added to 100 mg of tissue for cell lysis, vigorously mixed with 0.2 ml chloroform, and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min. The aqueous phase was removed and mixed with 0.5 ml of isopropanol to allow RNA precipitation. The RNA was precipitated by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 8 min and then washed with 1 ml of 75% ethanol. The dry RNA pellet was dissolved in RNase-free water. cDNA was synthesized using the first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription (RT) (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Following synthesis of cDNA, the following primers were used for Lyn PCR: forward, 5′-CCA CCA AGA TCT AGA AAT ATG GGA TGT ATT AAA TC; reverse, 5′-TGT CTC GAG CTA AGC GTA ATC TGG AAC ATC GTA TGG GTA CAT CCA CTT CGG TTG CTG CTG ATA CTG CCC TTC TG (restriction sites used for cloning purposes are underlined). The reverse primer also contains a HA sequence (italicized bold letters) to discriminate between exogenous and endogenous expression of Lyn. Previous studies have shown that introduction of a HA tag at the 3′ end of Lyn does not interfere with its function (22). PCR was performed using the following conditions: an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min and a final step of 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega, Madison, WI). Several clones were sequenced to determine the correct sequence. The correct clones were digested (BglII and XhoI), gel purified, and religated into retroviral vector MIGR1 at the corresponding sites (BglII and XhoI).

Construction of a Lyn expression vector with the unique domain deleted was achieved as follows. First, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector containing the full-length Lyn cDNA to generate two HpaI sites flanking the unique domain of Lyn using the following primers: primer A (Lyn forward), 5′-CAG AGG AAC AGT TAA CAT TGT GGG TGG CCT TTA TAC; primer B (Lyn reverse), 5′-GTA TAA GGC CAC CAC AAT GTT AAC TTG TTC CTC TGG; primer C (Lyn forward), 5′-CCA CCA AGA TCT AGA AAT ATG GGA GTT AAC AAA TCA AAA AGG; primer D (Lyn reverse), 5′-CCT TTT TGA TTT GTT AAC TCC CAT ATT TCT AGA TCT TGG TGG. These primers flank Lyn's unique domain (3′ and 5′ regions, respectively) and contain HpaI sites (underlined). PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, Foster City, CA). PCR products were digested with HpaI and religated. A second round of site-directed mutagenesis using primers E (Lyn forward; 5′-CCA AGT CTA GAA ATA TGG GAT GTG ACA TTG TGG TGG CCT TAT AC) and F (Lyn reverse; 5′-GTA TAA GGC CAC CAC AAT AAT GTC ACA TCC CAT ATT TCT AGA TCT TGG) was performed to restore the HpaI sites to the original Lyn sequence. All clones were verified for accuracy by sequencing, digested with BglII and XhoI, and religated into the retroviral vector MIGR1 at the corresponding sites (BglII and XhoI).

Transduction and expression of various constructs in BMMCs.

Retroviral supernatants for transduction of MCps were generated using the Phoenix ecotropic packaging cell line transfected with retroviral vector plasmids (cDNAs encoding WT and mutant Lyn) using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection and filtered through 0.45-μm membranes. BMMCs were suspended in IMDM containing 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and prestimulated in non-tissue culture plates supplemented with SCF (50 ng/ml) and IL-3 (10 ng/ml) for 48 h prior to retroviral infection on fibronectin fragments. After infection, cells were sorted to homogeneity based on EGFP expression. Transduced cells were grown in BMMC medium for an additional 2 to 3 weeks and analyzed by flow cytometry for KIT and IgE receptor expression.

Proliferation assay.

Cells were starved by replacing complete medium with IMDM without serum or growth factors for 6 h of incubation. Starved cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 25 × 104/ml and stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-3 or 50 ng/ml SCF for 48 h. Cells were pulsed with 1.0 μCi of [3H] thymidine (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) for 6 h at 37°C prior to harvesting. Cells were harvested using an automated 96-well cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD), and thymidine incorporation was determined as counts per minute.

Identification of mast cells in tissues.

Indicated tissues from the four genotypes were harvested and fixed in 10% buffered formalin, sectioned, and stained with toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For each sample, the mast cells stained purple were counted in 10 to 12 fields under ×200 magnification utilizing Leica Microsystems DM4000B equipment. Average numbers of mast cells in a given field are reported. For identification of mast cells in the peritoneal cavity, 5 ml of sterile PBS free of Ca2+ and Mg+ was injected intraperitoneally into mice and fluid was allowed to equilibrate in the peritoneum for 5 min. Three milliliters of lavage fluid was retrieved, and the total number of cells was determined after red cell lysis.

Quantitative PCR analysis.

Quantitative PCR analysis was performed essentially as described previously (21).

RESULTS

Enhanced PI3K activity due to deficiency of Lyn results in increased growth of BMMCs in response to SCF.

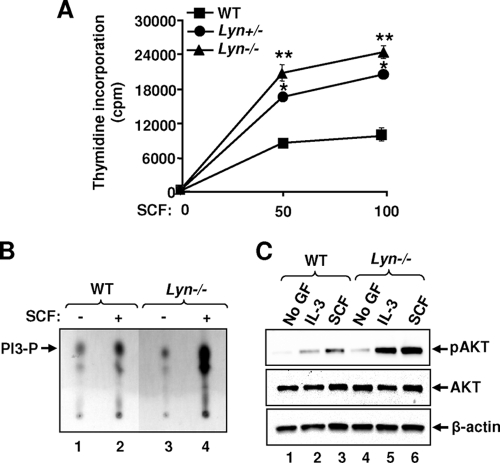

Previous studies have provided conflicting results with respect to the role of SFKs in the SCF-induced growth of mast cells. To clarify the role of the Lyn SFK in mast cell growth, we initiated a detailed and systematic study. We used a well-established in vitro BMMC model to examine the growth of cells lacking Lyn. As shown in Fig. 1A, deficiency or haploinsufficiency of the Lyn SFK in BMMCs results in enhanced growth in the presence of multiple different concentrations of SCF, suggesting that the Lyn SFK negatively regulates KIT-induced proliferation. Importantly, loss of one allele of Lyn in these cells appears to be sufficient to induce hyperproliferation in response to SCF (Fig. 1A).

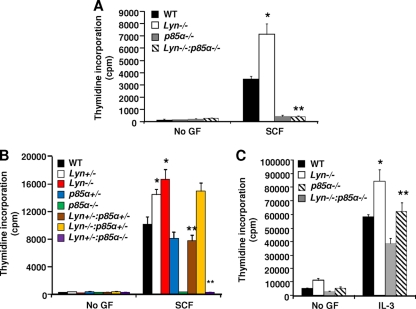

Fig. 1.

Deficiency of Lyn causes increased growth and enhanced PI3K activation in BMMCs. (A) BMMCs derived from WT, Lyn+/−, and Lyn−/− mice were starved in the absence of growth factors (GF) and subjected to a proliferation assay for 48 h. Shown is the amount of thymidine incorporation in an independent experiment performed in replicates of three with two different doses of SCF (50 and 100 ng/ml). The line graph represents the mean thymidine incorporation (counts per minute) ± the standard deviation in a representative experiment *, P < 0.05, Lyn+/− versus WT; **, P < 0.05, Lyn−/− versus WT. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. (B and C) BMMCs from WT and Lyn−/− mice (5 × 106) were starved, suspended in IMDM, and stimulated with cytokines, and lysates were analyzed for PI3K and AKT activation, respectively. Arrows indicate the levels of PI3P and pAKT in each lane. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

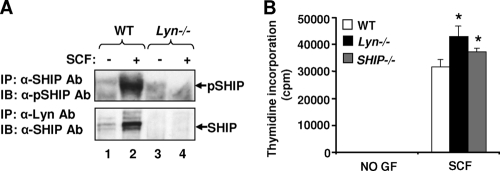

In an effort to identify the biochemical basis of this observation, we examined the activation of a series of signaling molecules downstream from KIT known to be regulated by SFKs, including PI3K and ERK mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase. Of all of the signaling pathways examined, we consistently observed elevated activation of PI3K in Lyn-deficient BMMCs compared to that in WT controls (Fig. 1B, lane 4). Consistent with the presence of elevated PI3K activity in these cells, Lyn deficiency also resulted in enhanced activation of AKT, a downstream substrate of PI3K, in response to both SCF and IL-3 (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6). To determine the mechanism of enhanced KIT-induced PI3K/AKT activation in Lyn-deficient BMMCs, we hypothesized that perhaps Lyn plays a crucial role in regulating the activation of a negative regulator of PIP3 in these cells, such that in the absence of its activation, PIP3 is not completely hydrolyzed to PIP2 (i.e., its activation is not completely turned off). To test this, we first examined the activation of SHIP in Lyn−/− BMMCs. In mast cells, SHIP plays an essential role in dephosphorylating PIP3 to PIP2 and in negatively regulating KIT/SCF-induced growth. To determine if Lyn regulates the phosphorylation of SHIP and physically associates with it, we performed IP experiments with BMMCs derived from WT and Lyn−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 2A, complete loss of Lyn in BMMCs resulted in loss of SHIP phosphorylation compared to controls (lane 2 versus lane 4). To assess whether loss of SHIP phosphorylation was in part a result of impaired binding between Lyn and SHIP in response to SCF, we performed IP followed by WB analysis. As shown in Fig. 2A, a significant increase in binding between Lyn and SHIP was observed in WT cells stimulated with SCF (lane 2). In contrast, the binding between Lyn and SHIP was completely absent in Lyn-deficient BMMCs (Fig. 2A, lane 4). Consistent with the impaired phosphorylation of SHIP in Lyn−/− BMMCs, the growth of BMMCs derived from Lyn- and SHIP-deficient mice was also comparable (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that Lyn regulates the phosphorylation of SHIP by physically associating with it, which is necessary for normal regulation of SCF-induced signaling in BMMCs.

Fig. 2.

Lyn regulates the phosphorylation of SHIP in BMMCs. (A) Loss of SHIP activation due to Lyn deficiency in response to SCF stimulation in BMMCs. BMMCs derived from WT and Lyn−/− mice were starved and stimulated with SCF. Cell lysates were subjected to IP using an anti-SHIP or an anti-Lyn antibody (Ab). The immunoprecipitated (IP) protein complex was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and WB analysis was performed using an anti-phospho-SHIP (anti-pSHIP) or an anti-SHIP antibody. Arrows indicate the levels of phosphorylated and total SHIP, respectively, in each lane. Similar results were observed in two independent experiments. (B) Deficiency of SHIP in BMMCs mimics the enhanced growth observed in Lyn−/− cells. BMMCs derived from WT, Lyn−/−, and SHIP−/− mice were growth factor (GF) starved and subjected to a proliferation assay for 48 h. Shown is the amount of thymidine incorporation from an independent experiment performed in replicates of three in response to SCF. Bars represent the mean thymidine incorporation (counts per minute) ± the standard deviation in a representative experiment. *, P < 0.05, Lyn−/− and SHIP−/− versus WT. No significant difference in the growth of Lyn−/− versus SHIP−/− BMMCs was seen. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments.

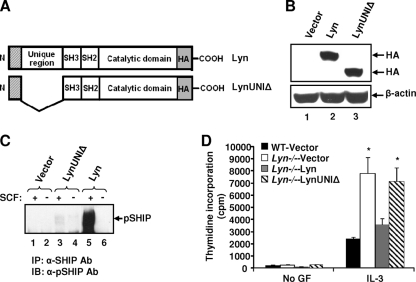

The enhanced growth of BMMCs in response to SCF in the absence of Lyn was intriguing, in light of the continuous expression of other SFKs in these cells, including Hck and Fgr (data not shown). To explore this further, we examined the amino acid sequences of the family members Lyn, Hck, and Fgr. We found significant conservation at the amino acid level in all of the domains of these family members, except for the amino-terminal unique domain, also known as the SH4 domain (2). We hypothesized that perhaps the SH4 domain of Lyn is uniquely involved in regulating the phosphorylation of SHIP. To test this, we cloned the full-length form of Lyn, as well as a mutant version of Lyn lacking the unique domain (LynUNIΔ), and expressed it in Lyn-deficient BMMCs. Figure 3A shows schematics of WT Lyn and the mutant Lyn construct lacking the unique domain. Figure 3B shows the expression of exogenous WT Lyn and the LynUNIΔ construct in Lyn-deficient BMMCs. Due to the lack of the unique domain, the LynUNIΔ construct migrates faster than WT Lyn in a WB analysis (Fig. 3B, lane 2 versus lane 3). While restoring Lyn-deficient BMMCs with the full-length version of Lyn restored SHIP phosphorylation (Fig. 3C), expression of LynUNIΔ in Lyn-deficient BMMCs did not restore the phosphorylation of SHIP (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the impaired phosphorylation of SHIP in Lyn−/− BMMCs bearing LynUNIΔ, the growth of these cells was similar to that of Lyn−/− and SHIP−/− BMMCs, while Lyn−/− BMMCs expressing the full-length version of Lyn completely restored growth to WT levels (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these results suggest a role for Lyn-induced PI3K activity in regulating cytokine-induced growth in BMMCs and an important role for Lyn's unique domain in regulating the phosphorylation of a critical negative regulator of PI3K activity, SHIP.

Fig. 3.

The unique domain of Lyn regulates SHIP phosphorylation. (A) Schematic structures of the full-length WT version of Lyn and a mutant version of Lyn lacking its unique domain (LynUNIΔ). (B) Expression of WT Lyn and LynUNIΔ in Lyn-deficient BMMCs. Lyn−/− BMMCs were transduced with a retroviral construct expressing either the full-length WT version of Lyn or LynUNIΔ. EGFP-positive cells were sorted to homogeneity and used to perform WB analysis using an anti-HA antibody (upper panel) and β-actin antibody (lower panel). (C) Lyn−/− BMMCs expressing the empty vector (MIGR1), WT Lyn, or LynUNIΔ were starved of growth factors (GF) and stimulated with SCF. Lysates were subjected to IP using an anti-SHIP antibody (Ab), followed by WB analysis using an anti-phospho-SHIP (anti-pSHIP) antibody. Similar results were observed in two independent experiments. (D) Cells described in panels B and C were subjected to a proliferation assay for 48 h and pulsed with [3H]thymidine. Shown is the amount of thymidine incorporation in response to IL-3 from an independent experiment performed in replicates of three. Bars represent the mean thymidine incorporation (counts per minute) ± the standard deviation. *, P < 0.05, WT-Vector versus Lyn-Vector and LynUNIΔ. Similar results were obtained in four independent experiments.

Loss of Lyn in BM cells results in enhanced BMMC maturation.

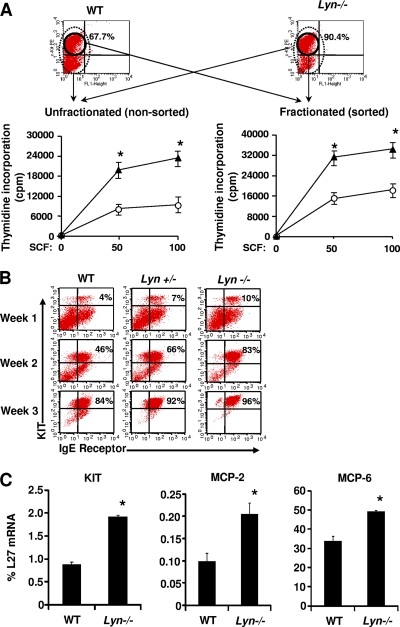

In an effort to determine if the enhanced proliferation of Lyn-deficient BMMCs seen was not simply a result of increased KIT expression, we compared the expression of KIT in WT cells with that in Lyn-deficient cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, deficiency of Lyn in BMMCs results in a significantly higher percentage of KIT+ cells as opposed to that of WT controls. To assess whether the increased SCF-induced growth in Lyn-deficient BMMCs shown in Fig. 1 was not simply due to increased KIT expression, we sorted WT and Lyn−/− BMMCs on the basis of KIT expression and subjected equal number of sorted cells to a proliferation assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, both KIT-sorted and unfractionated Lyn-deficient cells showed higher proliferation in response to SCF than did controls. Thus, the enhanced cytokine-induced growth due to Lyn deficiency is cell intrinsic and not necessarily a result of an increased number of KIT-positive cells.

Fig. 4.

Deficiency of Lyn in MCps results in enhanced BMMC maturation. (A) Enrichment of Lyn−/− KIT+ mast cell progenitors further enhances SCF-induced proliferation. Two- to 3-week-old MCps from WT and Lyn−/− BM were subjected to KIT staining and sorted to homogeneity for KIT expression. We subjected 5 × 104 KIT+-sorted (fractionated) or nonsorted (unfractionated) MCps to SCF-induced proliferation for 48 h and pulsed them with [3H]thymidine. Shown is the amount of thymidine incorporation into unfractionated and fractionated [KIT-sorted] mast cell progenitors at two different concentrations of SCF (50 and 100 ng/ml). Lines denote the mean thymidine incorporation (counts per minute) ± the standard deviation from an independent experiment performed in replicates of three. *, P < 0.05, Lyn−/− versus WT. (B) BM cells from WT, Lyn+/−, and Lyn−/− mice were cultured under conditions that induce BMMC maturation. Cells were harvested weekly up to 3 weeks and stained with antibodies that recognize KIT and IgE receptor. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the levels of KIT and IgE receptor expression at the end of each week. Shown are dot blot profiles of one of several experiments from the indicated genotypes analyzed at the end of weeks 1, 2, and 3. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of relative expression of mast cell markers associated with differentiation, including KIT, MCP-2, and MCP-6. Expression is normalized to L27. Values (percent L27 mRNA) are expressed as the mean results of experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate the standard deviation. *, P < 0.001, WT versus Lyn−/−; n = 3.

The increase in the number of KIT-positive cells in cultures derived from Lyn-deficient BM led us to hypothesize that perhaps Lyn deficiency, in addition to modulation of KIT expression, also impacts the overall maturation of BMMCs. To assess this further, we first examined the maturation of BMMCs from BM cells derived from WT, Lyn+/−, and Lyn−/− mice. As shown in Fig. 4B, BM cells cultured under conditions that encourage BMMC maturation, as assessed by the acquisition of cell surface KIT and IgE receptor positivity, demonstrated a significantly greater frequency of KIT and IgE receptor doubly positive cells in cultures lacking Lyn than did WT controls at all of the times examined (5.3 ± 0.62 [WT] versus 8.8 ± 0.91 [Lyn−/−] and 35.8 ± 6.48 [WT] versus 65.2 ± 8.15 [Lyn−/−] at the end of 1 and 2 weeks of culture, respectively [n = 5, P < 0.05]). Importantly, the enhanced maturation of BMMCs due to Lyn deficiency was dose dependent, as haploinsufficiency of Lyn also resulted in a significant increase in the maturation BMMC over that of WT controls. Thus, loss of Lyn not only results in enhanced cytokine-induced growth in BMMCs, but it also accelerates the rate of maturation of these cells. Consistent with the increase in KIT and IgE receptor cell surface expression in BMMCs lacking Lyn, a quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of genes associated with BMMC maturation, including those for KIT, MCP-2, and MCP-6, was also increased in Lyn−/− BMMCs over that in WT controls (Fig. 4C).

Enhanced KIT-induced growth of Lyn-deficient BMMCs is mediated via the p85α regulatory subunit of PI3K.

In Fig. 1, we showed that hyperactivation of PI3K due to Lyn deficiency results in enhanced KIT-induced growth. In the KIT receptor, PI3K is activated once the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K is recruited to tyrosine 719 in the intracellular domain of KIT. Once p85α is recruited to KIT, it binds to the p110 catalytic subunit, thereby generating PIP3 and PIP2 and subsequently activating downstream substrates, including the guanine exchange factors Rac, Rho, Vav, and AKT, by binding the pleckstrin homology domain. We next assessed whether the enhanced growth observed in Lyn-deficient BMMCs in response to SCF is mediated via the PIP3 generated in response to the binding of the p85α subunit of PI3K to the activated KIT receptor. We crossed Lyn-deficient mice with p85α-deficient mice. This genetic cross yielded mice of several distinct genotypes, including mice deficient in the expression of both p85α and Lyn. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, complete deficiency of both Lyn and p85α in BMMCs completely ameliorated the SCF-induced hyperproliferation observed in Lyn-deficient BMMCs. Furthermore, haploinsufficiency of p85α in the setting of Lyn haploinsufficiency was sufficient to completely rescue the SCF-induced hyperproliferation seen in Lyn+/− mutant cells in response to SCF stimulation (Fig. 5B). A modest correction in the hyperproliferation of BMMCs completely lacking Lyn and heterozygous for p85α was also observed relative to Lyn−/− mutant BMMCs (Fig. 5B). These results provide genetic evidence for a nonredundant role for p85α in Lyn-induced hyperproliferation of BMMCs in response to SCF. While BMMCs deficient in both Lyn and p85α did not respond to SCF stimulation (Fig. 5A), the IL-3-induced hyperproliferation observed in Lyn-deficient cells was normalized to WT levels in the setting of p85α deficiency (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that Lyn and p85α play distinct roles in KIT- and IL-3 receptor-induced proliferation in BMMCs.

Fig. 5.

Opposing roles for Lyn and p85α in BMMC growth. (A, B, and C) Loss of a single or two alleles of the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K in the setting of Lyn heterozygosity or homozygosity results in impaired BMMC growth. BMMCs from mice of the indicated genotypes were subjected to cytokine-induced proliferation for 48 h and pulsed with [3H]thymidine. Bars denote the average amounts of thymidine incorporation (counts per minute) ± the standard deviation in a representative experiment. Similar results were observed in three or four independent experiments. (A) *, P < 0.05, WT versus Lyn−/−; **, P < 0.05, Lyn−/− versus Lyn−/− p85α−/−. (B) *, P < 0.05, WT versus Lyn+/− and Lyn−/−; **, P < 0.05, Lyn+/− or Lyn−/− versus Lyn+/− p85α−/−, and Lyn+/− or Lyn−/− versus Lyn+/− p85α+/−. (C) *, P < 0.05, WT versus Lyn−/−; **, P < 0.05, Lyn−/− versus Lyn−/− p85α−/−. GF, growth factor.

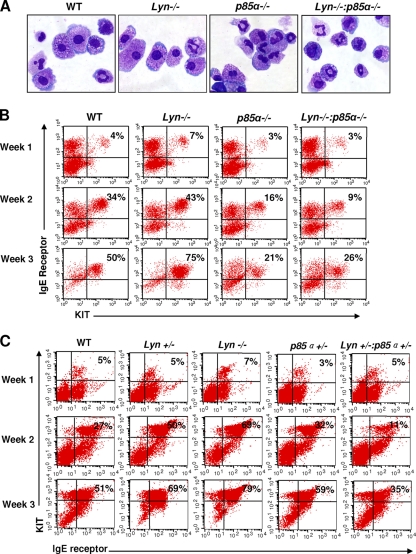

To assess if the enhanced rate of BMMC maturation observed in Lyn-deficient BM cells is also mediated via the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K, we examined BMMC maturation in WT, Lyn−/−, and p85α−/− cells, as well as in cells lacking both p85α and Lyn (i.e., double-knockout [DKO] cells), by performing cytospin analysis. While deficiency of Lyn and p85α resulted in correction of the IL-3-induced hyperproliferation associated with Lyn deficiency (Fig. 5C), loss of both Lyn and p85α significantly impaired the maturation of DKO BMMCs compared to that of WT or Lyn-deficient BMMCs (Fig. 6A and B). In particular, we observed that deficiency of Lyn alone in cultures induced a higher frequency of the development of cells that resembled more mature BMMCs than in WT controls or cells lacking the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K (Fig. 6A). The differences in morphology were apparent at the end of the second, third, and fourth weeks of culture (Fig. 6A and data not shown). To further explore the possibility of altered BMMC maturation due to Lyn deficiency, we systematically monitored the acquisition and emergence of KIT and IgE receptor doubly positive cells at the end of every week of culture in vitro in cells derived from WT, Lyn−/−, p85α−/−, and DKO mice. While the frequencies of KIT and IgE receptor doubly positive cells on day 0 in BM from the four genotypes were similar (data not shown), soon after and at the end of weeks 1, 2, and 3, the maturation of Lyn+/− and Lyn−/− deficient BMMCs was significantly enhanced relative to that of controls (Fig. 6B and C). In contrast, cells lacking p85α or both Lyn and p85α showed a profound reduction in the number of cells doubly positive for KIT and IgE receptor expression (Fig. 6B, 8 ± 1.09 [Lyn−/−] versus 4 ± 0.75 [DKO] and 43 ± 9.4 [Lyn−/−] versus 10.5 ± 3.12 [DKO] at the end of 1 and 2 weeks of culture, respectively [n = 3, P < 0.05]). Likewise, haploinsufficiency of p85α in the setting of Lyn haploinsufficiency significantly repressed the maturation of BMMC relative to that of WT controls (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrate that while IL-3-induced proliferation of DKO cells is rescued to WT levels, IL-3-induced maturation of BMMCs is significantly inhibited in DKO cells relative to that in controls. Thus, IL-3 receptor-induced signals involved in regulating the growth and maturation of BMMCs downstream from Lyn and p85α can be uncoupled.

Fig. 6.

Deficiency of p85α in Lyn−/− BM cells represses maturation of BMMCs. BMMCs were derived from WT, Lyn−/−, p85α−/−, and Lyn−/− p85α−/− mice. Cells were harvested after the indicated number of weeks and stained with Giemsa (A) or antibodies that recognize KIT and the IgE receptor (B). (A) Shown are representative cytospins of BMMC cultures derived from mice of the four genotypes. (B and C) Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating the expression of KIT and the IgE receptor in doubly positive cells at the indicated time points. The value in the upper right quadrant of each dot blot is the percentage of BM cells that are doubly positive for KIT and IgE receptor expression at the indicated times during culture. Similar findings were observed in BMMCs derived from two to four independent experiments.

Fig. 8.

Schematic describing signaling via cytokine receptors in BMMCs involving SHIP, Lyn, and the p85α subunit of class IA PI3K. Upon ligand stimulation, the intracellular cytokine receptor domain is phosphorylated and recruits p85α to the receptor. This results in the generation of PIP3. PIP3 is hydrolyzed to PIP2 by SHIP, which regulates BMMC growth (in the case of KIT) and maturation (in the case of the IL-3 receptor). Our results show that the Lyn SFK regulates the activation of SHIP in MCps in response to cytokine stimulation by regulating its phosphorylation. Loss of Lyn expression in MCps results in a phenotype similar to that observed in MCps deficient in SHIP. The mechanism by which Lyn, SHIP, and p85α regulate mast cell maturation via the IL-3 receptor involves PI3K-mediated modulation of Mitf expression, which is associated with AKT and ERK1/2 activation. Furthermore, while loss of Lyn or SHIP in MCps results in similar functional outcomes via KIT and IL-3R, a requirement for p85α in KIT- and IL-3R-induced function(s) is distinct.

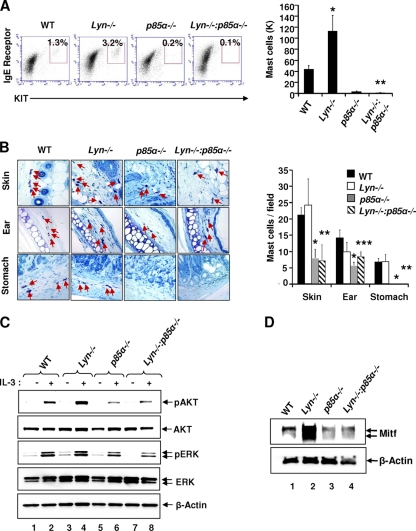

Consistent with our in vitro results obtained with BMMCs from the four genotypes, similar results were obtained in vivo with peritoneal cavity-derived mast cells from the four genotypes. As shown in Fig. 7A, an increase in the number of mast cells was observed in the peritoneal cavities of Lyn-deficient mice relative to that in WT controls. In contrast, a significant reduction in the number and percentage of mast cells was observed in the peritoneal cavities of p85α-deficient and DKO mice relative to those in WT and Lyn-deficient mice. While the numbers of mast cells in the skin, ears, and stomachs of p85α-deficient and DKO mice were similar and significantly reduced relative to those in WT mice, the increase in the number of mast cells noted in the peritoneal cavities of Lyn−/− mice was not observed in other tissues derived from these animals (Fig. 7B). Thus, deficiency of Lyn results in an increase in the number of mast cells in some, but not all, tissues in vivo. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Lyn differentially regulates mast cell numbers in vivo and cooperates with p85α in positively regulating mast cell growth and maturation.

Fig. 7.

Differential regulation of mast cells due to Lyn deficiency in vivo. (A) Cells from the peritoneal cavities of mice of the indicated genotypes were harvested and stained with antibodies against KIT and the IgE receptor. Representative dot blots indicate peritoneal cavity-derived mast cells from mice of the indicated genotypes stained with anti-KIT and anti-IgE receptor antibodies. The value in the upper right quadrant of each dot blot is the percentage of peritoneal cavity-derived cells that were doubly positive for KIT and IgE receptor expression. The bar graph represents a quantitative assessment of the total number of mast cells in 5 ml of peritoneal lavage fluid from mice of the indicated genotypes. Data are pooled from five independent experiments. Five to seven mice were used to generate the data in the left panel, and four to six mice were used to generate the data in the right panel. *, P < 0.05, WT versus Lyn−/−; **, P < 0.05, WT or Lyn−/− versus DKO. (B) Representative photomicrographs of toluidine blue-stained tissue sections derived from mice of the indicated genotypes. Arrows indicate tissue mast cells from mice of the indicated genotypes. The bar graph shows a quantitative assessment of toluidine blue-positive mast cells in the indicated tissues. n = 4 (mean ± standard deviation). *, P < 0.05, p85α−/− versus WT and Lyn−/−; **, P < 0.05, DKO versus WT and Lyn−/−; ***, P < 0.05, DKO versus WT. (C) Hyperactivation of AKT in Lyn−/− BMMCs is inhibited in the setting of p85α deficiency. BMMCs derived from mice of the indicated genotypes were starved in the absence of growth factors and stimulated with IL-3. Cell lysates were subjected to WB analysis using antibodies that recognize the activated versions of the indicated signaling proteins. The activation status of AKT and ERK1/2 is shown. Similar findings were obtained in two independent experiments. (D) Loss of Lyn expression in BMMCs results in enhanced expression of Mitf. BMMCs derived from WT, Lyn−/−, p85α−/−, and Lyn−/− p85α−/− mice were lysed and subjected to WB analysis using an anti-Mitf antibody. Arrows indicated the levels of expression of Mitf and β-actin (loading control) in each lane. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

Reduced activation of AKT and ERK MAP kinase in Lyn−/− p85α−/− BMMCs.

To assess the biochemical basis of the reduced maturation of BMMCs derived from Lyn and p85α DKO mice relative to that of BMMCs derived from Lyn knockout mice, we examined the activation of AKT and ERK1/2. Both of these molecules have been shown to be activated in mast cells; however, their respective contributions to BMMC maturation are not known. As shown in Fig. 7C, loss of Lyn in BMMCs results in enhanced activation of AKT. In contrast, loss of p85α in BMMCs results in reduced AKT activation. Surprisingly, loss of both Lyn and p85α in BMMCs results in AKT activation that is similar to that in p85α-deficient BMMCs rather than that in WT BMMCs. In addition, a modest reduction in the activation of ERK1/2 is also observed in both p85α−/− and DKO BMMCs relative to that in WT controls and Lyn−/− BMMCs. These results suggest that reduced BMMC maturation in DKO cells is likely due to reduced AKT and ERK1/2 activation. Thus, while deficiency of both Lyn and p85α restores IL-3-induced BMMC growth to WT levels in spite of reduced AKT and ERK activation, reduction of AKT and ERK activation in DKO BMMCs is associated with altered maturation relative to that of WT controls.

Lyn regulates the expression of Mitf in BMMCs via p85α.

One of the major transcription factors known to regulate mast cell maturation in BMMCs is Mitf (15, 39, 40, 45). Mitf is known to regulate not only the expression of the gene for KIT but also the expression of several other genes in BMMCs (38). Since a profound reduction in the expression of the gene for KIT and overall BMMC maturation was observed in cells lacking both Lyn and p85α, in spite of normal IL-3-induced growth, we assessed the expression of Mitf in BMMCs derived from all four genotypes. As shown in Fig. 7D, while the expression of Mitf in Lyn-deficient BMMCs correlated directly with increased BMMC maturation and KIT expression, both p85α-deficient and DKO BMMCs showed a profound reduction in the expression of Mitf compared to that in Lyn-deficient BMMCs and WT BMMCs. These results suggest that Lyn and p85α cooperate in regulating BMMC maturation in part by regulating the expression of Mitf downstream from AKT and ERK1/2, which is significantly reduced in DKO BMMCs.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing a systematic approach, including BMMCs derived from mice haploinsufficient for Lyn, our results demonstrate that Lyn regulates the phosphorylation of SHIP in response to cytokine stimulation. Specifically, we show that the unique domain (i.e., SH4) of Lyn is involved in SHIP binding and phosphorylation in response to cytokine stimulation. We show that Lyn-deficient cells expressing a mutant version of Lyn that is unable to bind and phosphorylate SHIP behaves in a manner similar to that of SHIP- or Lyn-deficient BMMCs. We show that loss of Lyn or Lyn haploinsufficiency negatively regulates not only the growth of BMMCs but also their maturation, due mostly to its inability to hydrolyze p85α-induced PIP3, which results in enhanced AKT activation (Fig. 8). Our results show that haploinsufficiency of p85α (p85α+/−) in the background of Lyn heterozygosity (Lyn+/−) corrects SCF-induced hyperproliferation associated with Lyn+/− BMMCs. Interestingly, BMMCs devoid of both p85α and Lyn demonstrate a proliferation that is substantially lower than that of WT BMMCs. These results suggest that Lyn, in addition to negatively regulating cytokine-induced growth (by regulating the phosphorylation of SHIP), also positively impacts the growth of BMMCs. Our findings suggest that the conditions that result in positive versus negative growth regulation in BMMCs in response to cytokine stimulation via Lyn depend on the level of expression of p85α and on the level of activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Based on our findings, we believe that under normal circumstances, SCF-KIT interactions result in the activation of Lyn and p85α (Fig. 8). Once p85α is activated, it generates PIP3, which is hydrolyzed to PIP2 by SHIP (whose activation is partly controlled by Lyn). Lyn, in addition to phosphorylating SHIP and negatively regulating KIT-induced functions, is also capable of positively regulating KIT signaling (dotted lines in Fig. 8). In contrast, BMMCs that completely lack the expression of Lyn but are normally able to activate p85α and generate normal levels of PIP3 lack the ability to hydrolyze PIP3 to PIP2 due to impaired SHIP phosphorylation. Therefore, these BMMCs demonstrate hypersensitivity to SCF. A similar situation is observed in BMMCs that are heterozygous for the expression of Lyn but normal for the expression of p85α. In both of these scenarios, the positive regulation of KIT by Lyn is masked by Lyn's negative regulation (i.e., regulation of SHIP by Lyn is dominant). In the situation were BMMCs are haploinsufficient for both Lyn and p85α, SCF-induced hyperproliferation is not only corrected (in Lyn+/− cells) but further reduced compared to that in WT BMMCs. We predict that this is partly due to the positive effect of Lyn on KIT signaling. In this scenario, SHIP activation may be only partly reduced due to Lyn haploinsufficiency and since haploinsufficiency of p85α may contribute to reduced PIP3 generation in response to SCF stimulation (to a lesser degree than that seen in Lyn−/− MCps), this may allow the positive effect of Lyn to be manifested. Likewise, BMMCs completely lacking the expression of Lyn (Lyn−/−) in the setting of p85α heterozygosity show only some reduction in SCF-induced growth. Finally, BMMCs completely lacking the expression of both Lyn (Lyn−/−) and p85α (p85α−/−) are likely not to result in the generation of PIP3 in response to SCF because of a lack of p85α expression. In this situation, whether SHIP is activated by Lyn or not does not really matter. Under these conditions, the positive effect of Lyn is likely to dominate.

In contrast to the lack of KIT-induced growth signaling in DKO BMMCs, IL-3 receptor-induced growth and maturation signals utilize Lyn and p85α in a distinct manner. While IL-3 receptor-induced AKT and ERK1/2 signaling in DKO cells is clearly impaired, growth in response to IL-3 in these cells is corrected to WT levels, although the maturation of these cells is clearly defective. These results suggest that AKT and ERK1/2 are likely not the major contributors to the growth and proliferation of DKO BMMCs in response to IL-3. Our results suggest that perhaps AKT and ERK1/2 play a role in regulating the expression of Mitf in DKO BMMCs and therefore contribute to their maturation. How precisely AKT and ERK1/2 regulate Mitf expression is under investigation.

In spite of the importance of Mitf in mast cell growth and development (19), little is known about the mechanisms that regulate Mitf expression in mast cells. We show that in BMMCs, the Lyn SFK and p85α play an essential role in regulating the expression of Mitf, which is associated with reduced AKT and ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 8). We show a significant reduction in Mitf protein expression in p85α−/− BMMCs and a significant increase in Lyn−/− BMMCs compared to that in WT controls. Importantly, the increase in the expression of Mitf in Lyn−/− BMMCs is associated with accelerated maturation, which is modulated in the setting of p85α deficiency. Precisely how this occurs is unclear, but PI3K plays an essential role in regulating p90Rsk (48). Rsk has been shown to regulate the activation of CREB (48). CREB plays an essential role in the transcriptional regulation of Mitf in melanocytes (37). Furthermore, downstream of PI3K, AKT regulates the activation of GSK3β (48). Activation of GSK3β via AKT also regulates aspects of Mitf posttranslational modification (42). In melanocytes, Rsk and ERK2 activation plays an essential role in the posttranslational modification of Mitf. Whether similar pathways are operative in BMMCs is under investigation. Taken together, our findings demonstrate a critical role for Lyn, SHIP, and p85α in regulating both the growth of BMMCs and their maturation in part by regulating the activation of AKT and ERK1/2 and the expression of Mitf.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marilyn Wales for her administrative support.

This work was supported in part by grants R01HL075816 and R01HL077177 from the National Institute of Health to R.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson S. M., Jorgensen B. 1995. Activation of src-related tyrosine kinases by IL-3. J. Immunol. 155:1660–1670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown M. T., Cooper J. A. 1996. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1287:121–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costa J. J., Weller P. F., Galli S. J. 1997. The cells of the allergic response: mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. JAMA 278:1815–1822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Damen J. E., Ware M. D., Kalesnikoff J., Hughes M. R., Krystal G. 2001. SHIP's C-terminus is essential for its hydrolysis of PI3P and inhibition of mast cell degranulation. Blood 97:1343–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Durand B., et al. 1994. Long-term generation of human mast cells in serum-free cultures of CD34+ cord blood cells stimulated with stem cell factor and interleukin-3. Blood 84:3667–3674 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fukao T., et al. 2002. PI3K-mediated negative feedback regulation of IL-12 production in DCs. Nat. Immunol. 3:875–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galli S. J., Nakae S., Tsai M. 2005. Mast cells in the development of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 6:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galli S. J., Zsebo K. M., Geissler E. N. 1994. The kit ligand, stem cell factor. Adv. Immunol. 55:1–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gurish M. F., Austen K. F. 2001. The diverse roles of mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 194:F1–F5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helgason C. D., et al. 1998. Targeted disruption of SHIP leads to hemopoietic perturbations, lung pathology, and a shortened life span. Genes Dev. 12:1610–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernandez-Hansen V., Mackay G. A., Lowell C. A., Wilson B. S., Oliver J. M. 2004. The Src kinase Lyn is a negative regulator of mast cell proliferation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75:143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huber M., et al. 1998. The src homology 2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) is the gatekeeper of mast cell degranulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:11330–11335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huber M., et al. 1998. Targeted disruption of SHIP leads to Steel factor-induced degranulation of mast cells. EMBO J. 17:7311–7319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huber M., Kalesnikoff J., Reth M., Krystal G. 2002. The role of SHIP in mast cell degranulation and IgE-induced mast cell survival. Immunol. Lett. 82:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Isozaki K., et al. 1994. Cell type-specific deficiency of c-kit gene expression in mutant mice of mi/mi genotype. Am. J. Pathol. 145:827–836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawakami Y., et al. 2000. Redundant and opposing functions of two tyrosine kinases, Btk and Lyn, in mast cell activation. J. Immunol. 165:1210–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirshenbaum A. S., et al. 1999. Demonstration that human mast cells arise from a progenitor cell population that is CD34(+), c-kit(+), and expresses aminopeptidase N (CD13). Blood 94:2333–2342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kitamura Y. 1989. Heterogeneity of mast cells and phenotypic change between subpopulations. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7:59–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kitamura Y., Morii E., Jippo T., Ito A. 2002. Effect of MITF on mast cell differentiation. Mol. Immunol. 38:1173–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kitamura Y., Yokoyama M., Matsuda H., Ohno T., Mori K. J. 1981. Spleen colony-forming cell as common precursor for tissue mast cells and granulocytes. Nature 291:159–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kondo T., Johnson S. A., Yoder M. C., Romand R., Hashino E. 2005. Sonic hedgehog and retinoic acid synergistically promote sensory fate specification from bone marrow-derived pluripotent stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4789–4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kovárová M., et al. 2001. Structure-function analysis of Lyn kinase association with lipid rafts and initiation of early signaling events after Fcepsilon receptor I aggregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:8318–8328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee Y. N., et al. 2011. KIT signaling regulates MITF expression through miRNAs in normal and malignant mast cell proliferation. Blood 117:3629–3640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lennartsson J., et al. 1999. Phosphorylation of Shc by Src family kinases is necessary for stem cell factor receptor/c-kit mediated activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and c-fos induction. Oncogene 18:5546–5553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y., Shen B. F., Karanes C., Sensenbrenner L., Chen B. 1995. Association between Lyn protein tyrosine kinase (p53/56lyn) and the beta subunit of the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) receptors in a GM-CSF-dependent human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line (M-07e). J. Immunol. 155:2165–2174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Linnekin D., DeBerry C. S., Mou S. 1997. Lyn associates with the juxtamembrane region of c-Kit and is activated by stem cell factor in hematopoietic cell lines and normal progenitor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:27450–27455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Q., et al. 1999. SHIP is a negative regulator of growth factor receptor-mediated PKB/Akt activation and myeloid cell survival. Genes Dev. 13:786–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu-Kuo J. M., Fruman D. A., Joyal D. M., Cantley L. C., Katz H. R. 2000. Impaired kit- but not FcepsilonRI-initiated mast cell activation in the absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85alpha gene products. J. Biol. Chem. 275:6022–6029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Metcalfe D. D., Baram D., Mekori Y. A. 1997. Mast cells. Physiol. Rev. 77:1033–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Munugalavadla V., et al. 2008. The p85alpha subunit of class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates the expression of multiple genes involved in osteoclast maturation and migration. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:7182–7198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nishizumi H., Yamamoto T. 1997. Impaired tyrosine phosphorylation and Ca2+ mobilization, but not degranulation, in lyn-deficient bone marrow-derived mast cells. J. Immunol. 158:2350–2355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nocka K., Buck J., Levi E., Besmer P. 1990. Candidate ligand for the c-kit transmembrane kinase receptor: KL, a fibroblast derived growth factor stimulates mast cells and erythroid progenitors. EMBO J. 9:3287–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Odom S., et al. 2004. Negative regulation of immunoglobulin E-dependent allergic responses by Lyn kinase. J. Exp. Med. 199:1491–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O'Laughlin-Bunner B., Radosevic N., Taylor M. L., Shivakrupa, et al. 2001. Lyn is required for normal stem cell factor-induced proliferation and chemotaxis of primary hematopoietic cells. Blood 98:343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Parravicini V., et al. 2002. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat. Immunol. 3:741–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pazdrak K., Schreiber D., Forsythe P., Justement L., Alam R. 1995. The intracellular signal transduction mechanism of interleukin 5 in eosinophils: the involvement of lyn tyrosine kinase and the Ras-Raf-1-MEK-microtubule-associated protein kinase pathway. J. Exp. Med. 181:1827–1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Price E. R., et al. 1998. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone signaling regulates expression of microphthalmia, a gene deficient in Waardenburg syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33042–33047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shahlaee A. H., Brandal S., Lee Y. N., Jie C., Takemoto C. M. 2007. Distinct and shared transcriptomes are regulated by microphthalmia-associated transcription factor isoforms in mast cells. J. Immunol. 178:378–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stechschulte D. J., et al. 1987. Effect of the mi allele on mast cells, basophils, natural killer cells, and osteoclasts in C57Bl/6J mice. J. Cell. Physiol. 132:565–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stevens J., Loutit J. F. 1982. Mast cells in spotted mutant mice (W Ph mi). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 215:405–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stevens R. L., et al. 1994. Strain-specific and tissue-specific expression of mouse mast cell secretory granule proteases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:128–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takeda K., et al. 2000. Ser298 of MITF, a mutation site in Waardenburg syndrome type 2, is a phosphorylation site with functional significance. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9:125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Timokhina I., Kissel H., Stella G., Besmer P. 1998. Kit signaling through PI 3-kinase and Src kinase pathways: an essential role for Rac1 and JNK activation in mast cell proliferation. EMBO J. 17:6250–6262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Torigoe T., O'Connor R., Santoli D., Reed J. C. 1992. Interleukin-3 regulates the activity of the LYN protein-tyrosine kinase in myeloid-committed leukemic cell lines. Blood 80:617–624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsujimura T., et al. 1996. Constitutive activation of c-kit in FMA3 murine mastocytoma cells caused by deletion of seven amino acids at the juxtamembrane domain. Blood 87:273–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ueda S., et al. 2002. Critical roles of c-Kit tyrosine residues 567 and 719 in stem cell factor-induced chemotaxis: contribution of src family kinase and PI3-kinase on calcium mobilization and cell migration. Blood 99:3342–3349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wei S., et al. 1996. Critical role of Lyn kinase in inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Immunol. 157:5155–5162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wymann M. P., Marone R. 2005. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase in disease: timing, location, and scaffolding. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yousefi S., Hoessli D. C., Blaser K., Mills G. B., Simon H. U. 1996. Requirement of Lyn and Syk tyrosine kinases for the prevention of apoptosis by cytokines in human eosinophils. J. Exp. Med. 183:1407–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]