Abstract

The human pathogen Corynebacterium diphtheriae utilizes hemin and hemoglobin as iron sources for growth in iron-depleted environments. The use of hemin iron in C. diphtheriae involves the dtxR- and iron-regulated hmu hemin uptake locus, which encodes an ABC hemin transporter, and the surface-anchored hemin binding proteins HtaA and HtaB. Sequence analysis of HtaA and HtaB identified a conserved region (CR) of approximately 150 amino acids that is duplicated in HtaA and present in a single copy in HtaB. The two conserved regions in HtaA, designated CR1 and CR2, were used to construct glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins (GST-CR1 and GST-CR2) to assess hemin binding by UV-visual spectroscopy. These studies showed that both domains were able to bind hemin, suggesting that the conserved sequences are responsible for the hemin binding property previously ascribed to HtaA. HtaA and the CR2 domain were also shown to be able to bind hemoglobin (Hb) by the use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method in which Hb was immobilized on a microtiter plate. The CR1 domain exhibited a weak interaction with Hb in the ELISA system, while HtaB showed no significant binding to Hb. Competitive binding studies demonstrated that soluble hemin and Hb were able to inhibit the binding of HtaA and the CR domains to immobilized Hb. Moreover, HtaA was unable to bind to Hb from which the hemin had been chemically removed. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of CR domains from various Corynebacterium species revealed several conserved residues, including two highly conserved tyrosine (Y) residues and one histidine (H) residue. Site-directed mutagenesis studies showed that Y361 and H412 were critical for the binding to hemin and Hb by the CR2 domain. Biological assays showed that Y361 was essential for the hemin iron utilization function of HtaA. Hemin transfer experiments demonstrated that HtaA was able to acquire hemin from Hb and that hemin bound to HtaA could be transferred to HtaB. These findings are consistent with a proposed mechanism of hemin uptake in C. diphtheriae in which hemin is initially obtained from Hb by HtaA and then transferred between surface-anchored proteins, with hemin ultimately transported into the cytosol by an ABC transporter.

INTRODUCTION

Corynebacterium diphtheriae is the cause of the severe upper respiratory tract disease diphtheria. C. diphtheriae is a Gram-positive bacterium that secretes diphtheria toxin, an iron-regulated exotoxin that is the primary cause of the morbidity and mortality associated with human infection by this organism (11). While diphtheria toxin was one of the first virulence factors shown to be regulated by iron, the transcriptional regulation of numerous virulence determinants was found in recent years to be controlled by the iron content in the growth medium (12). Some of these iron-regulated factors, which have been identified and characterized in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, are involved in the uptake of extracellular iron. Iron acquisition in bacteria involves a variety of mechanisms, including high-affinity siderophore uptake systems (46) and various membrane or cell wall-anchored binding proteins that sequester iron compounds at the cell surface (4, 8, 12). Iron uptake systems that utilize surface-exposed binding proteins are common in bacteria, especially in pathogenic species, and they are frequently involved in the acquisition of iron from host sources, including transferrin, lactoferrin, and various heme proteins (7, 29, 39). Studies of Gram-negative bacteria have identified outer membrane proteins that specifically bind transferrin, lactoferrin, hemin, and hemoproteins such as Hb (29, 39). The hemin binding proteins are proposed to extract the bound hemin, after which the hemin is mobilized into the bacterial cytosol via an ABC transporter and its cognate periplasmic binding protein (17, 38). Hemophores, low-molecular-weight secreted heme binding proteins, have also been previously described in studies of some Gram-negative organisms (23).

Recently, mechanisms involved in iron acquisition in Gram-positive bacteria have been characterized. As with Gram-negative species, Gram-positive organisms utilize siderophores and binding protein-dependent uptake systems for iron transport. In the absence of an outer membrane, siderophore uptake in Gram-positive bacteria involves fewer components than are required by gram-negative bacteria; only a membrane-anchored substrate binding lipoprotein and its cognate ABC transporter appear to be required for mobilization of the ferric-siderophore complex into the cell (8, 19, 35). Analysis of hemin acquisition systems in Gram-positive species, however, has revealed transport mechanisms of greater complexity than those observed with siderophore uptake. Staphylococcus aureus utilizes the Isd (iron-regulated surface determinant) system to transport hemin (27). The Isd system is composed of the surface proteins IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH-HarA, which are covalently anchored to the cell wall by the sortase enzymes SrtA (IsdA, IsdB, and IsdH-HarA) and SrtB (IsdC) (4, 27). All of the cell wall-anchored Isd proteins are able to bind hemin, and certain Isd proteins bind various hemoproteins such as Hb or haptoglobin (Hp). The binding to hemin or hemoproteins by the Isd components occurs at conserved regions designated NEAT (near-iron transporter) domains (3, 16, 31). It is proposed that hemin uptake by the Isd system involves the initial binding of a hemoprotein, such as Hb (IsdB or IsdH), Hp, or the Hp-Hb complex (IsdH), at the surface followed by the removal of hemin and the subsequent transfer of hemin via an Isd protein relay system (IsdB/IsdH → IsdA → IsdC → IsdE) (25, 31, 43, 48). Once hemin is bound by the plasma membrane-anchored substrate binding protein IsdE, the ABC transporter, which includes the proteins IsdD and IsdF, mobilizes the hemin into the cytosol, where iron is liberated from the hemin molecule through the activity of the heme-degrading monooxygenases IsdG and IsdI (37). Hemin acquisition in Bacillus anthracis involves both surface-anchored proteins and secreted hemophores, all of which bind hemin and contain conserved NEAT domains. In B. anthracis, the secreted hemophores IsdX1 and IsdX2 are able to remove hemin from Hb; however, only isdX1 has been shown to transfer the extracted hemin to the sortase-anchored cell wall IsdC protein, which facilitates the mobilization of hemin to an ABC transporter (14, 26). B. anthracis also contains an S-layer homology protein, BslK, which is a hemin binding NEAT protein localized to the surface. Hemin bound by Bslk is transferred to the cell wall IsdC protein (42). Hemin transport in Streptococcus pyogenes involves the use of the heme binding and membrane-anchored proteins Shp and Shr and a heme-specific ABC transporter encoded by siaABC (6, 22, 24, 47). Shp and Shr both contain heme binding NEAT domains and are localized to the cell surface; however, unlike the Isd cell wall proteins, Shp and Shr lack sortase-anchoring motifs and are proposed to associate with the cell surface through a hydrophobic C-terminal and a positively charged tail region (15). Recent studies have proposed that Shr is composed of multiple domains, including two heme binding NEAT domains, one of which may have the capacity to reduce bound hemin. Shr also contains an Hb binding N-terminal region that is distinct from either of the NEAT domains and has the ability to bind various cell surface matrix molecules, suggesting that Shr may also function as an adhesin (30).

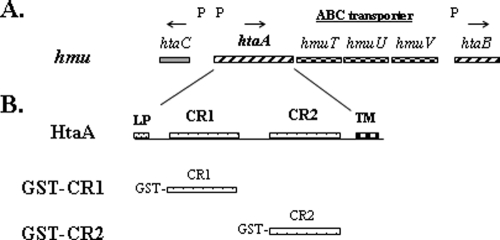

In C. diphtheriae, hemin transport utilizes HmuTUV, an iron-regulated ABC-type transporter, and HtaA, a surface-anchored hemin binding protein (1, 13, 36). The genes encoding the hemin transport system are grouped in a six-gene cluster, designated hmu, that contains three distinct iron- and DtxR-regulated transcriptional regions (Fig. 1A) (1, 18). The hmuTUV and htaA genes constitute a single operon, while htaB and htaC are independently transcribed (1, 18). Mutations in the hmuTUV genes or htaA result in a reduced ability to use hemin and Hb as iron sources, suggesting that the ABC transporter and HtaA most likely function in the uptake of hemin (1). Deletion of the entire hmu operon does not abolish the use of hemin and Hb as iron sources, which suggests that additional hemin uptake systems are present in C. diphtheriae (1). HtaA is a 61-kDa protein that contains an N-terminal leader peptide and a hydrophobic C-terminal region that is predicted to anchor the protein to the cytoplasmic membrane. Previous studies showed that HtaA is exposed on the cell surface and contains two conserved repeats of approximately 150 amino acids, which are designated CR (for “conserved region”) (1). No functions have been determined for the conserved region, and it shows no significant sequence homology to the NEAT domains found in other Gram-positive hemin binding proteins. HtaB also binds hemin and contains a single copy of the CR and, like HtaA, is exposed on the cell surface and is proposed to be anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane through a hydrophobic C-terminal region. Mutants encoded by htaB were not defective in the use of hemin or Hb as iron sources, and no function has been determined for HtaB (1). However, it seems likely that HtaB has a function in hemin-iron transport or utilization, since it is an iron-regulated, surface-exposed hemin binding protein that is encoded in a genetic cluster involved in hemin transport. The product of htaC is predicted to be a membrane-associated protein of unknown function.

Fig. 1.

(A) Genetic map of the hmu locus in C. diphtheriae. P indicates the presence of DtxR-regulated promoters, and the arrows show the direction of transcription. (B) Structural features of HtaA. LP, leader peptide; CR1 and CR2, conserved regions; TM, transmembrane region. Glutathione S-transferase fusion constructs with CR1 and CR2 domains (GST-CR1 and GST-CR2) are shown.

The C. diphtheriae hmuO gene encodes a heme oxygenase that is also involved in the use of heme as an iron source in C. diphtheriae (20, 33). HmuO is a cytosolic protein that is able to enzymatically cleave the heme molecule, resulting in the release of the heme-bound iron (45). The hmuO gene is not associated with the hemin transport hmu gene cluster, although expression of hmuO is regulated by DtxR and iron and by heme sources (34).

In this study, we extended our analysis of the hemin binding properties of the HtaA and HtaB proteins in C. diphtheriae. Both CR domains in HtaA bind hemin and Hb, although HtaA and the CR2 domain exhibited significantly stronger binding to Hb than CR1. Soluble hemin and Hb could inhibit binding of HtaA to immobilized Hb. Conserved tyrosine and histidine residues in the CR domains were shown to be important for hemin and hemoglobin (Hb) binding and for the hemin-iron utilization activity for HtaA. Hemin transfer experimental results suggest that HtaA directly obtains hemin from Hb and subsequently transfers hemin to HtaB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Escherichia coli strains DH5α and TOP10 (Invitrogen) were used for routine cloning, and C. diphtheriae strain 1737 was described previously (1, 32). Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was used for routine culturing of E. coli, and C. diphtheriae strains were grown in heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, MI) containing 0.2% Tween 80 (HIBTW). Bacterial stocks were maintained in 20% glycerol at −80°C. Antibiotics were added to LB medium at 12.5 μg/ml for chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml for kanamycin, and 100 μg/ml for ampicillin; kanamycin was added at 50 μg/ml for C. diphtheriae cultures in HIBTW medium. Iron-depleted HIBTW medium was made by the addition of EDDA [ethylenediamine di(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid] at 6 μg/ml (unless indicated otherwise). Modified PGT (mPGT) is a semidefined low-iron medium that has been previously described (41). Antibiotics, EDDA, Tween 80, hemin (bovine), and hemoglobin (human) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Hemoglobin used for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) studies was obtained from MP Biomedical.

Plasmid construction.

PCR-derived DNA fragments were initially cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and genomic DNA derived from C. diphtheriae strain 1737 was used as a template for all PCRs. pGEX-6P-1 vector (GE Healthcare) was used for expression of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins GST-CR1 and GST-CR2; both constructs contained the GST tag at the N terminus. For the construction of GST-CR1, primers R-CR1A (5′-GCGCTCGAGCTAGGATTGGACACTACGTTT-3′) and GEXFHta-GST (1) were used for PCR to amplify a 627-bp fragment carrying the CR1 domain. Primers F-CR2 (5′-GCGGATATCAGATGCGACTCGAACATCC-3′) and RXhoHta-TM (1) were used to amplify a 768-bp fragment harboring the CR2 domain. The GST-HtaA construct was previously described (1). The Strep-HtaA expression plasmid was constructed as follows: primers FstrepHtaA (5′-GCGCATATGGCAAGCTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAGGGTGCAGCTGATAGCAATCAATGC-3′) and RHtA-TM (1) were used to amplify an approximately 1.7-kb fragment carrying the htaA gene that was lacking the leader sequence and the C-terminal transmembrane region. The FstrepHtaA primer encodes an NdeI restriction site and the eight-amino-acid Strep-tag II peptide (underlined). The PCR product carrying the strep-tag htaA sequence was ligated into pET24a expression vector at the NdeI and HindIII restriction sites. The DNA sequences of all PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutants were made using QuikChange Lightning kits (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 125 ng of each primer containing the targeted base change and 50 ng of the plasmid template were used in the QuikChange reaction. Methylated template DNA was removed from the reaction by digestion with DpnI restriction endonuclease, and mutagenized DNA was recovered by transformation into XL1-Gold competent cells. The presence of the base changes was confirmed by sequence analysis. The plasmids used for site-directed mutagenesis were pGEX-6P-1, containing the cloned htaA gene and the various CR subdomains, and pCC1 (Epicentre), encoding the htaA gene (pCC-htaA). Since the cloned htaA gene is unstable at high copy numbers in E. coli, the htaA gene was initially cloned into low-copy-number pCC1 vector to carry out the mutagenesis. Following mutagenesis, the insert on pCC-htaA was ligated into the EcoRV site in vector pKN2.6Z (13) and then transformed into C. diphtheriae 1737htaAΔ for the complementation studies.

Protein expression and analysis.

E. coli strain BL21(DE3) carrying the cloned htaB gene on pET28a+ expression vector (1) was grown in 100 ml of LB medium at 37°C to mid-log phase, at which time 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added and the cultures were allowed to grow for an additional 2 to 3 h before harvesting. The cultures were washed in 10 ml of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and the pellet was stored at −20°C overnight. The pellet was thawed and resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole (pH 8.0) at 4°C, and the bacteria were lysed in a French pressure cell followed by removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The soluble fraction containing the His-tagged HtaB protein was collected and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen) by a batch affinity method according to the manufacturer's instructions. When appropriate, the His tag was removed by the use o a thrombin cleavage capture kit (EMD Chemicals, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified protein was dialyzed overnight into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 20% glycerol and stored at −20°C.

Expression of HtaA and its CR domains by the use of pGEX-6P-1 vector (GE Healthcare) followed a similar procedure to that described above for the pET expression system. The GST-tagged constructs were found predominantly in the soluble fraction after induction at 27°C and lysis of the bacteria by the use of a French press or BugBuster protein extraction reagent (EMD Chemicals, Inc.). The GST fusion constructs were purified using GST resin (GE Healthcare) by a batch method following the manufacturer's instructions. For some experiments, the GST tag was removed from GST-HtaA by the use of PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The Strep-HtaA protein was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) following the procedures and conditions described above for the pGEX-6P-1 constructs, with the exception that induction was performed overnight at 4°C. The Strep-HtaA protein was purified using Strep-Tactin Superflow columns (IBA, Gottingen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The purified protein was dialyzed into 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–150 mM NaCl with 20% glycerol.

For routine analysis of protein preparations, proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (21) and stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer's instructions. All of the proteins expressed from the mutated genes exhibited normal stability.

Hemin binding analysis.

Purified GST-tagged fusion proteins were analyzed for their hemin binding properties by UV-visual spectroscopy using a Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer. Proteins (2 μM) in PBS buffer containing glycerol were assessed for their ability to bind hemin at various concentrations as indicated. Proteins were incubated in the presence of hemin for at least 15 min at room temperature before spectrophotometric analysis. UV-visual absorption scans were done using wavelengths between 280 and 600 nm. Absorbance spectra for all protein-hemin samples were referenced to those of a cuvette that contained the respective hemin concentrations in PBS buffer in the absence of protein.

Detection of heme-dependent peroxidase activity.

The chromogenic compound TMBZ (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine), which turns blue in the presence of heme-dependent peroxidase activity, was used to detect hemin-protein complexes as previously described (1, 40). Protein samples (1 μg) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the presence or absence of hemin and were then subjected to electrophoresis on two separate SDS-PAGE gels; one gel was stained with Coomassie blue and the other with TMBZ. Hemin was prepared in 0.1 N NaOH and was used at 1.5 μM. Incubation of samples in the absence of hemin was done with 0.1 N NaOH. Proteins were not boiled or exposed to reducing agents prior to SDS-PAGE.

Hb binding ELISA.

An ELISA method was developed to assess the ability of various test proteins to bind immobilized Hb. Polystyrene 96-well microtiter plates (Costar) were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of 25 μg/ml Hb in PBS. After incubation with Hb, the plates were washed with PBST (PBS, 0.05% Tween 20) and blocked for 1 h with 5% Blotto–PBST followed by incubation with 200 nM test protein (50 μl) for 1 h. After incubation, the plates were washed with PBST, and primary antibodies anti-Gst (1:1,000), anti-HtaB (1:50), anti-HtaA (1:50), and anti-Hb (1:1,000) (Sigma) were then added to the plates for 1 h, followed by an additional wash and then a 1-h incubation with appropriate alkaline phosphate-labeled secondary antibodies. Incubations were routinely performed at 37°C; however, GST-HtaA showed comparable binding to Hb when the incubations were done at room temperature (data not shown). The plates were developed in the dark with 50 μl of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (Sigma) at room temperature. A final absorbance reading was taken when the GST-HtaA sample achieved an optical density at 405 nm (OD405) of approximately 1. In some experiments, GST-HtaA was used to coat the microtiter plates to assess Hb binding to immobilized HtaA.

Hemoglobin iron utilization assays.

The hemoglobin iron utilization assay has been described previously (1, 20). Briefly, C. diphtheriae 1737 strains were grown for 20 to 22 h at 37°C in HIBTW and then inoculated at an OD600 of 0.2 into fresh HIBTW that contained 6 μg/ml of the iron chelator EDDA. Strains were grown for several hours at 37°C until log phase, at which time bacteria were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in mPGT medium, and then inoculated at an OD600 of 0.03 into fresh mPGT medium that contained various supplements as indicated. After 20 to 22 h of growth at 37°C, the OD600 of the cultures was determined.

Removal of hemin from Hb.

The removal of hemin from Hb was done essentially as described previously (5). Briefly, a solution of 6 μM Hb was adjusted to approximately pH 2.6 with 0.1 M HCl followed by the addition of methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) at an equal volume. The Hb was mixed briefly with the MEK, and the mixture was cooled to 4°C. The lower phase containing the apo-Hb was removed, and buffer exchange with PBS was performed using a 10,000-nominal-molecular-weight-limit (NMWL) Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit. Hemin removal from Hb was confirmed by UV-visual spectroscopy. An apo-Hb aliquot was combined with an equal molar amount of hemin to generate holo-Hb. The reconstitution of holo-Hb was confirmed by UV-visual spectroscopy.

Competition studies with hemin and Hb.

Competitive binding studies were done to determine whether soluble hemin or Hb could inhibit the binding of GST-HtaA, GST-CR1, or GST-CR2 to immobilized Hb. The procedure utilized the Hb ELISA format described above. Microtiter plates coated with Hb and blocked with Blotto and PBST were prepared as described above for the Hb ELISA. GST-HtaA at 120 nM and GST-CR1 and GST-CR2 at 200 nM were incubated with Hb or hemin at various concentrations in blocking buffer at room temperature. After approximately 1 h, this mixture was applied to the Hb-coated microtiter plates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Following the incubation, the plates were washed with PBST, and the anti-GST antibodies (GE Healthcare) at a dilution of 1:1,000 were added to the plates for 1 h. This incubation was followed by an additional wash and then incubations with appropriate alkaline phosphate-labeled secondary antibodies. The plates were developed in the dark with pNPP (Sigma). A final absorbance reading was taken when a GST-HtaA control sample (GST-HtaA not prebound with competitor) achieved an OD405 of approximately 1.

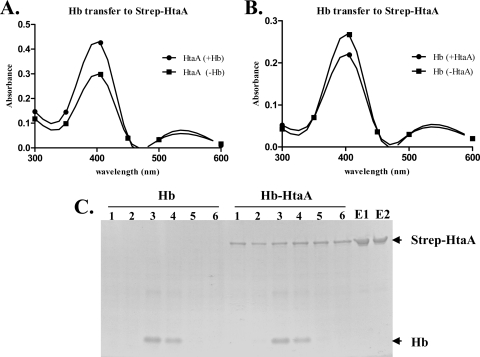

Hemin transfer experiments.

To assess hemin transfer from Hb to Strep-HtaA, 100 μl of purified Strep-HtaA at a 30 μM concentration was applied to a 0.2-ml Strep-Tactin column that was equilibrated with buffer W (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl). The column was washed three times with 0.2 ml of buffer W followed by the addition of 100 μl of 30 μM Hb (Sigma), which was allowed to migrate into the resin and incubate with the bound Strep-HtaA protein for 30 min at room temperature. The column was then washed four times with 0.2 ml of buffer W followed by elution of Strep-HtaA with buffer W containing 2.5 mM desthiobiotin. The Hb and Strep-HtaA fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and UV-visual spectroscopy to assess hemin binding. Control experiments, which employed either Hb alone or Strep-HtaA to which no Hb had been added, were performed in parallel to assess changes in hemin binding.

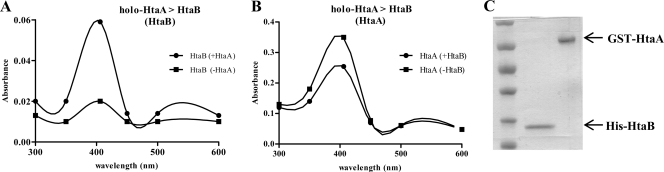

Hemin transfer from holo-GST-HtaA to HtaB was assessed using a His-tagged HtaB protein (1) at 3 μM that was mixed at a 1:6 molar ratio (HtaB:holo-HtaA) with holo-GST-HtaA as the hemin donor. Molar ratios of HtaB:holo-HtaA of 1:1 and 1:3 were also used, with similar results (not shown). The His-HtaB protein was allowed to prebind with equilibrated Talon resin (Clontech) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by washes containing 50 mM Na phosphate–300 mM NaCl (pH 7.0); this buffer was used for all washing and equilibration steps. Holo-GST-HtaA was added to the resin containing the bound His-HtaB protein, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The resin was then centrifuged, and the holo-GST-HtaA present in the supernatant was concentrated using a 10,000-NMWL Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter unit and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and UV-visual spectroscopy to determine purity and to assess hemin binding. His-HtaB was eluted from the resin with wash buffer containing 150 mM imidazole and processed as described for holo-GST-HtaA. Holo-Gst-HtaA was generated by incubation with hemin at a 2:5 molar ratio of Gst-HtaA to hemin and then dialyzed into PBS with 20% glycerol followed by a buffer exchanged into PBS with a 30,000-NMWL Centriprep filter cartridge (Millipore) to ensure removal of free hemin. As a control to compare changes in hemin binding, His-HtaB alone and holo-GST-HtaA without added His-HtaB were processed as described above.

Computer analysis.

Amino acid sequence similarity searches were done using the BLAST program (2) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The annotated genome sequence for C. diphtheriae strain NCTC13129 (9) is accessible in the EMBL/GenBank database at accession no. BX248. Multiple sequence alignments were done with ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/).

RESULTS

The CR domains in HtaA are hemin binding regions.

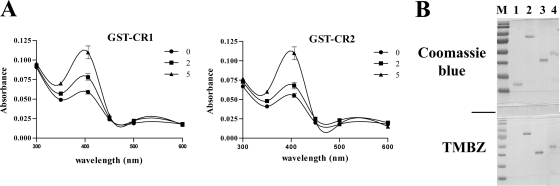

We previously showed that HtaA and HtaB are able to bind hemin; however, the regions critical for hemin binding were not identified (1). Since the CR domains are the only regions of significant sequence similarity between these proteins, we sought to determine whether these conserved sequences function as the site for hemin binding in HtaA. GST fusion constructs that contained an N-terminal GST tag fused in frame to each of the HtaA CR domains, designated GST-CR1 and GST-CR2, were generated using plasmid pGEX-6P-1 (Fig. 1B). We and others have previously shown that an N-terminal GST tag did not interfere with hemin binding by HtaA (1) or IsdA (16). The CR domain constructs were expressed in BL21(DE3), and the fusion proteins were purified using a GST affinity resin as described previously (1). UV-visual spectroscopy was used to analyze the hemin binding properties of the purified GST-CR1 and GST-CR2 peptides in the presence of various concentrations of hemin. Scans revealed that both GST-CR1 and GST-CR2 exhibited a Soret band at 406 nm (Fig. 2A), a unique absorbance signature that is characteristic of hemin binding proteins. As reported previously for HtaA and for other hemin binding proteins, some increase in absorbance in the 400-nm range was observed for both CR1 and CR2 in the absence of added hemin (Fig. 2A) (1, 16). This increased absorbance was likely due to the presence of hemin that was scavenged by the recombinant protein during the expression and purification process in E. coli. Protein staining with TMBZ, a chromogenic substrate used to detect heme-dependent peroxidase activity associated with hemin binding proteins, provided additional evidence that the CR1 and CR2 domains of HtaA bind hemin (Fig. 2B). As reported previously (1), the GST protein did not stain with TMBZ (Fig. 2B, lane 1) and showed no significant absorption peak in the 400-nm region in the presence of hemin (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A) CR1 and CR2 are hemin binding domains. UV-visual spectroscopy was used to examine the hemin binding properties of purified GST-CR1 and GST-CR2. Protein at 2 μM was incubated for 15 min in the presence of 0, 2, or 5 μM hemin prior to analysis. Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± standard deviations [SD] at 406 nm). (B) The hemin binding domains CR1 and CR2 exhibit hemin-dependent peroxidase activity in the presence of TMBZ and hemin. The top panel shows an SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1, GST; lane 2, GST-HtaA; lane 3, GST-CR1; lane 4, GST-CR2; M, molecular weight standard. The lower gel was stained with TMBZ to detect hemin binding proteins and was loaded identically to the Coomassie-stained gel.

HtaA is a hemoglobin binding protein.

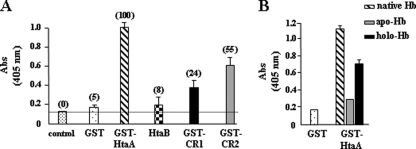

C. diphtheriae is capable of using Hb as an iron source, and mutations in htaA or in the hmuTUV genes result in a reduced ability to use Hb iron (1). The form of Hb used in these studies is primarily metHb, a heterodimeric form of Hb that exists in an oxidized state in which each α and β monomer binds to ferric heme (44). This oxidized, dimeric form of Hb is proposed to be the predominant form of Hb that invading pathogens would encounter during an infection. It was proposed that C. diphtheriae is able to acquire and transport hemin that is bound to Hb and that this uptake system utilizes the surface-exposed HtaA protein and other components encoded at the hmu locus. Although the mechanism by which Hb is used as an iron source is not known, it is possible that Hb iron utilization in C. diphtheriae requires a direct interaction between HtaA and Hb. To explore this possibility, we developed an ELISA plate method that measures the ability of a test protein to bind Hb that is immobilized on a microtiter plate. The ELISA procedure showed that HtaA strongly bound to Hb, while HtaB and the control protein, GST, showed no significant binding to the immobilized Hb (Fig. 3A). When soluble Hb was used as the test protein, it was able to bind to GST-HtaA immobilized on microtiter plates, providing additional evidence that HtaA binds Hb (data not shown). Moreover, removal of the GST tag from GST-HtaA had no effect on HtaA binding to immobilized Hb (data not shown). The GST-CR1 and GST-CR2 proteins both bind Hb, but at lower efficiency than HtaA, and the CR2 domain showed significantly stronger binding than CR1 (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

(A) HtaA and the CR domains bind Hb. Microtiter plates were coated with Hb (25 μg/ml), and various test proteins at 200 nM were analyzed for the ability to bind to the immobilized Hb (see Materials and Methods for details). Anti-GST antibodies were used as the primary antibodies to detect binding of test proteins (except for HtaB, which was detected by polyclonal antibodies specific for HtaB) (1). Polyclonal antibodies specific for HtaA (1) were also used in some experiments and provided results similar to those obtained with studies using anti-GST antibodies (not shown). Coloration on the plates was allowed to develop until the OD405 of the GST-HtaA construct reached approximately 1.0. The numbers in parenthesis indicate percent absorbance relative to the GST-HtaA value, which is set at 100%. The control experiment used no test protein, but all other processes were identical. Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± SD). (B) GST-HtaA binds poorly to apo-Hb. Various forms of Hb were immobilized to microtiter plates as described above and then examined for their ability to bind GST-HtaA (200 nM). The forms of Hb used to bind to the plates were as follows: native Hb (Hb used in the ELISA procedure as described for panel A); apo-Hb (Hb treated with MEK to remove hemin); holo-Hb (apo-Hb reconstituted with hemin). All three forms of Hb bound to microtiter plates equally well (not shown).

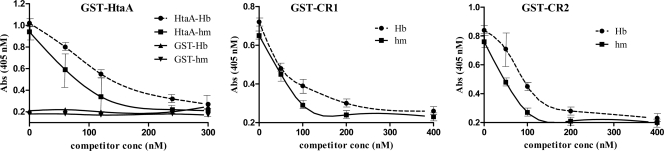

To determine whether the binding of Hb to the HtaA and the CR domains was specific, we performed competitive binding studies using the Hb ELISA. These experiments showed that prebinding of either hemin or Hb to HtaA or the CR domains resulted in reduced binding of these proteins to immobilized Hb (Fig. 4). The inhibition of binding to Hb by the test proteins (HtaA and the CR domains) was enhanced at increasing concentrations of the inhibitors (hemin or Hb), and full inhibition of binding to immobilized Hb was achieved at competitor concentrations that were equal to or greater than the test protein concentration (Fig. 4). The observation that soluble Hb inhibits the binding of HtaA and the CR domains to immobilized Hb suggests that the interaction of these proteins with Hb is specific. Moreover, the ability of hemin to specifically block binding of HtaA and the CR domains to Hb suggests that the interaction between HtaA and Hb may occur at the hemin moiety. To support this proposal, we chemically removed hemin from Hb (apo-Hb) and showed that HtaA binds poorly to apo-Hb but exhibits a significant increase in binding to apo-Hb reconstituted with hemin to form holo-Hb (Fig. 3B). While this observation suggests that binding between HtaA and Hb may occur through the hemin moiety, it is also possible that the binding of hemin by Hb results in a favorable conformation that allows interaction between these proteins. It was noted in these studies that the reconstituted holo-Hb bound HtaA at a reduced level compared to the native Hb, and we suspect this may have been caused by denaturation of a portion of the Hb sample during the hemin removal procedure as described previously (5). Control experiments showed that all three forms of Hb (apo, holo, and native) bound the microtiter plates equally well and that the α-GST antibody used to detect the GST-HtaA fusion protein did not recognize Hb and did not nonspecifically bind to the Blotto-treated ELISA plates (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Soluble Hb and hemin can compete with immobilized Hb for binding to HtaA and the CR domains. Soluble Hb and hemin (hm) at increasing concentrations (competitor conc.) were mixed with various test proteins (120 nM for HtaA and 200 nM for the CR domains). After incubation, the test proteins were assessed for the ability to bind Hb by the use of the plate ELISA system. GST was used as a negative control. Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± SD).

The CR domains contain conserved tyrosine and histidine residues that are critical for hemin binding.

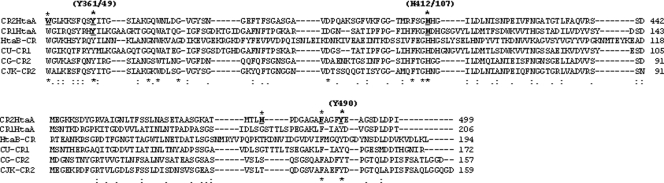

The CR domain was initially defined as a region that exhibited amino acid similarity of sequences within HtaA (CR1 and CR2) and also between HtaA and HtaB. The CR1 and CR2 domains of HtaA exhibit approximately 31% identity and 50% similarity over a region of 150 to 170 amino acids, while the CR2 domain shares approximately 27% identity and 38% similarity with the CR domain in HtaB. The CR1 domain of HtaA has slightly less homology with the CR of HtaB. A sequence alignment of the CR domains from HtaA and HtaB and from various HtaA homologs in related Corynebacterium species is shown in Fig. 5. While overall sequence similarities are low among these CR domains, two tyrosine residues and a histidine residue are conserved in all of these sequences. Tyrosine and histidine residues are known to coordinate the iron atom of heme in other well-characterized hemin binding proteins (16, 31), and it is possible that one or more of these conserved residues have a similar function in the CR domains.

Fig. 5.

Sequence alignment of the C. diphtheriae CR domains from HtaA (CR1 and CR2) and HtaB and from HtaA homologs in related Corynebacterium species. Strain and gene designations are as follows: CU-CR, C. ulcerans 712-htaA; CG-CR, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032-Cg10388; CJK-CR, C. jeikeium k411-jk0315. Conserved tyrosine and histidine residues are indicated above the sequence alignment, and residues with an asterisk above the sequence were changed to alanine in the mutagenesis studies. Asterisks below the sequence indicate sequence identity; colons and periods indicate sequence similarity.

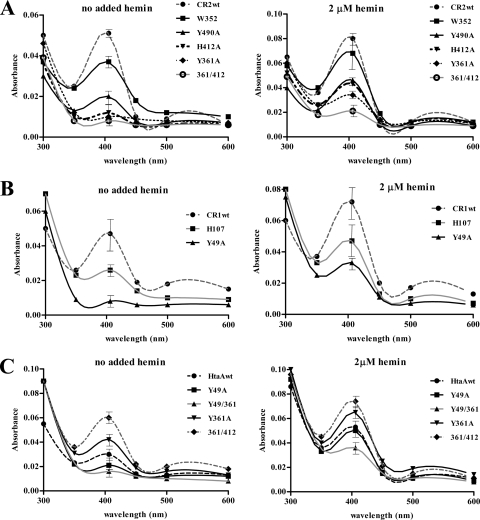

To determine the importance of the various conserved residues in the CR2 domain with regard to hemin binding, we used site-directed mutagenesis to change specific conserved residues to alanine. Both of the conserved tyrosines (Y361 and Y490) and the single conserved histidine (H412) were targeted for mutagenesis, as well as conserved phenylalanine (F486) and tryptophan (W352) residues (Fig. 5). A nonconserved histidine (H479) was also changed. GST-CR2 fusion proteins containing the altered amino acid sequences were expressed and purified and then examined by UV-visual spectroscopy for hemin binding. Compared to the wild-type CR2 domain, GST-CR2-Y361A and GST-CR2-H412A exhibited a significant decrease in absorbance at 406 nm in the presence of various hemin levels, indicating that changes at these residues have an extreme effect on the hemin binding properties of these proteins (Fig. 6A). The change at Y490 also resulted in a strong reduction in hemin binding, while the change at W352 produced a moderate reduction. The effects of alanine substitutions at H479 and F486 were not significantly different from those seen with wild-type GST-CR2 (not shown). Alanine substitution mutants were generated in the GST-CR1 construct at residues analogous to CR2-Y361 (Y49 in CR1) and CR2-H412 (H107 in CR1) (Fig. 5). UV-visual absorbance assay results for GST-CR1-Y49A and GST-CR1-H107A indicate that both proteins exhibit a strong reduction in the size of the Soret band at 406 nm relative to the GST-CR1 wild-type protein (Fig. 6B), an observation that suggests that these residues have similar roles in hemin binding in the CR1 and CR2 domains.

Fig. 6.

Conserved tyrosine and histidine residues are critical for hemin binding by the CR domains. UV-visual spectroscopy was used to assess the hemin binding capability resulting from amino acid substitutions in GST constructs of the CR2 domain (A) and the CR1 domain (B) and in full-length HtaA (C). Proteins were either incubated with 2 μM hemin or processed without added hemin prior to spectroscopy. Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± SD at 406 nm).

Amino acid substitutions were also generated in the full-length GST-HtaA fusion protein to assess the effect on hemin binding. Surprisingly, the GST-HtaA-Y361A change resulted in a significant (P < 0.05) increase in absorbance at 406 nm relative to the wild-type GST-HtaA protein results (Fig. 6C). The identical mutation in the GST-CR2 construct resulted in a sharp decrease in absorbance at 406 nm relative to the wild-type CR2 results (Fig. 6A). To determine whether the increased absorbance seen with GST-HtaA-Y361A was unique to the alanine substitution at Y361, additional amino acid substitutions, including Y361F, H412A, and the Y361A/H412A double substitution, were made in the CR2 domain of the full-length GST-HtaA protein. All of these constructs exhibited absorbance at 406 nm that was significantly higher than that seen with wild-type GST-HtaA both in the absence of added hemin and in the presence of 2 μM hemin (Fig. 6C and data not shown for H412A and Y361F). The GST-HtaA-Y49A construct, which includes a change in a conserved tyrosine in the CR1 domain of the full-length HtaA protein, resulted in a slight but not statistically significant decrease in absorbance at 406 nm compared to the wild-type results (Fig. 6C); as noted previously, the Y49A substitution in GST-CR1 strongly reduced hemin binding (Fig. 6B). The GST-HtaA-Y49A/Y361A double mutant, however, exhibited greatly diminished absorbance at 400 nm (Fig. 6C), which suggests that mutations in both CR1 and CR2 are required to significantly reduce hemin binding in the full-length HtaA protein.

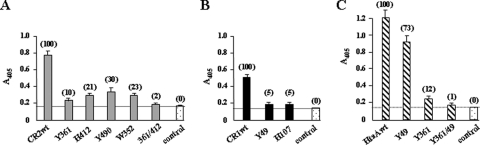

Specific tyrosine and histidine residues in the CR domains are required for Hb binding.

Amino acid changes introduced into GST-HtaA, GST-CR1, and GST-CR2 were examined for their effect on Hb binding. In the GST-CR2 protein, alanine substitutions at Y361, H412, Y490, and W352 all resulted in strongly reduced levels of Hb binding (Fig. 7A), while changes at F486 and H479 showed no defect in Hb binding relative to the wild-type results (not shown). Alanine substitutions in the CR1 domain at Y49 and H107 virtually abolished Hb binding (Fig. 7B). In the full-length GST-HtaA construct, the Y49A substitution reduced Hb binding by approximately 25%, while a Y361A substitution and a double alanine substitution (Y361/Y49) resulted in a sharp reduction in Hb binding relative to the wild-type protein results (Fig. 7C). Additional changes (Y361F, H412A, and Y361A/H412A) in GST-HtaA within the CR2 domain resulted in a decrease in Hb binding similar to that observed with Y361A (not shown). These findings suggest that the CR2 domain is responsible for most of the Hb binding detected in the full-length HtaA protein, since single amino acid changes (Y361 and H412) specifically within this domain reduced Hb binding by almost 90%.

Fig. 7.

Effect of amino acid substitutions in the HtaA CR domains on Hb binding. Hb binding by the various GST constructs (200 nM) was assessed using the previously described ELISA. Numbers in parentheses represent percent absorbance relative to the wild-type protein value, which is set at 100%. Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± SD).

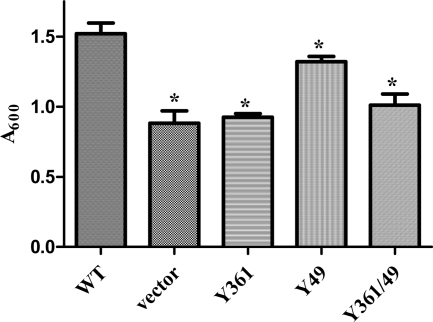

A conserved tyrosine in the CR2 domain is critical for HtaA function.

It was previously shown that strain 1737htaAΔ had a diminished ability to use Hb and hemin as iron sources relative to the wild-type strain, and it was also previously demonstrated that plasmid pKhtaA, which contains a copy of the wild-type htaA gene, was able to restore wild-type levels of growth to 1737htaAΔ in the presence of heme sources under low-iron conditions (1). To assess the effect of specific amino acid substitutions on the function of HtaA, conserved tyrosine residues were changed to alanine at Y361 and Y49 in the cloned htaA gene on plasmid pKhtaA. The cloned wild-type and mutated htaA genes were examined for the ability to stimulate growth of 1737htaAΔ in the presence of Hb. The results of the study indicated that the Y361A and Y361A/Y49A substitutions abolished the Hb iron utilization function of HtaA, since growth stimulation caused by the cloned htaAY361A gene or the double mutant htaAY361A/Y49A in 1737htaAΔ was not significantly different from that seen with the vector control (Fig. 8). The identical mutations in the GST-HtaA construct resulted in a 90% or greater reduction in Hb binding relative to the wild-type results (Fig. 7C). The Y49A mutation resulted in a small but significant reduction in growth stimulation compared to the results seen with the wild-type htaA gene (Fig. 8). These findings demonstrate a direct correlation between Hb binding by HtaA (Fig. 7C) and the ability to use Hb as an iron source. Similar growth results were obtained when 1.5 μM hemin was used in place of Hb as the source of iron (data not shown).

Fig. 8.

Conserved tyrosine residues in the CR2 and CR1 domains in HtaA are essential for optimal utilization of Hb as an iron source. Hb iron utilization assays were performed with C. diphtheriae strain 1737htaAΔ carrying the following plasmids: pKhtaA (wild type [wt]); pKN2.6Z (vector); pKhtaA-Y361A (Y361); pKhtaA-Y49A (Y49); pKhtaA-Y361A-Y49A (double mutant [Y361/49]). Values represent averages of the results from three independent experiments (± SD). Asterisks indicate a significant (P < 0.05) difference from the wild-type results.

HtaA acquires hemin from Hb.

The results of the Hb iron utilization assays suggest that HtaA functions in the acquisition of hemin from Hb, and we sought to determine whether hemin transfer to HtaA can be demonstrated in vitro using purified proteins. We initially intended to perform these hemin transfer studies using GST-HtaA as the recipient protein, but we determined that this fusion construct failed to bind to the GST resin at the high protein concentrations needed to execute these experiments. As an alternative, we constructed and utilized for the hemin transfer studies a Strep-tag–HtaA protein (Strep-HtaA), which was able to bind to Strep-Tactin resin at high levels. Moreover, the Strep-HtaA protein exhibited hemin and Hb binding properties similar to those of GST-HtaA (not shown). To demonstrate hemin transfer to HtaA, Strep-HtaA (30 μM) was prebound to Strep-Tactin resin and then incubated with Hb (30 μM) in a capped 0.2-ml column for 30 min. Following this incubation period, Hb was separated from Strep-HtaA after the column was washed with buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl. Strep-HtaA was subsequently eluted from the column with the same buffer containing 2.5 mM desthiobiotin. Absorbance of Strep-HtaA and Hb at 406 nm was assessed to determine hemin binding. As controls for these studies, Strep-HtaA and Hb were incubated separately with Strep-Tactin resin and processed as described above. The peak elution fraction of Strep-HtaA that was incubated with Hb exhibited consistently higher absorbance at 406 nm than the Strep-HtaA fraction that did not interact with Hb (Fig. 9A). No evidence of contaminating Hb was detected in the Strep-HtaA elution fraction after extensive washing (Fig. 9C [E1]), which indicates that the increase in absorbance at 406 nm was solely due to hemin binding to Strep-HtaA. Hb incubated with Strep-HtaA (+HtaA) showed a slight but reproducible decrease in absorbance at 406 nm compared to Hb incubated with the Strep-Tactin resin alone (−HtaA) (Fig. 9B). It was noted, however, that low levels of Strep-HtaA were detected in all of the washes (Fig. 9C [Hb-HtaA; lanes 1 to 6]). To correct for the background contamination in the peak Hb fraction (Hb-HtaA; lane 3), the UV-visual absorbance readings for wash 6 (lane 6), which included only the background Strep-HtaA protein, were subtracted from the peak Hb values for lane 3. Attempts to remove the contaminating Strep-HtaA from the washes were unsuccessful, even after adjusting the NaCl concentration in the wash buffer. Furthermore, the amount of Strep-HtaA loaded onto the column did not exceed the binding capacity of the resin. The heme transfer experiments with Hb and Strep-HtaA were performed multiple times and provided consistent results; however, due to variability in the protein levels obtained in each experiment, a representative experiment is shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

HtaA acquires hemin from Hb. (A) UV-visual spectroscopy of Strep-HtaA (30 μM) after incubation in the presence (+Hb) or absence (−Hb) of 30 μM Hb. (B) UV-visual spectroscopy of Hb (30 μM) after incubation in the presence (+HtaA) or absence (−HtaA) of Strep-HtaA (30 μM). (C) Results of SDS-PAGE showing separation of Strep-HtaA from Hb after a 30-min incubation. Hb lanes 1 to 6 represent the wash fractions in the Hb-only control experiment. Lane 3, which represents the peak Hb fraction, was used for UV-visual analysis as described for panel B. Hb-HtaA lanes 1 to 6 represent the wash fractions from the heme transfer experiment performed with Hb and Strep-HtaA. Lane 3, which represents the peak Hb fraction, was used for UV-visual analysis as described for panel B. Lane 6 represents measurement of the background contamination contributed by Strep-HtaA. Lanes E1 and E2 represent the elution fractions containing Strep-HtaA from the heme transfer experiment and the control experiment, respectively.

HtaB acquires hemin from HtaA.

HtaB is a surface-exposed hemin binding protein that, unlike HtaA, did not bind Hb when the ELISA method described above was performed. While no function for HtaB is known, its association with a hemin transport system and its ability to bind hemin suggest a possible role in hemin uptake. HtaB may function as a component in a hemin relay system in which hemin is moved through the cell wall via surface-anchored proteins, in similarity to hemin uptake mechanisms described in studies of other Gram-positive bacteria (24, 25, 47, 48). Since HtaA can acquire hemin from Hb, it is to be assumed that the hemin bound to HtaA is ultimately moved into the cytosol, and we sought to determine whether HtaB may function as an intermediate in this hemin transfer process. To determine whether HtaB can acquire hemin from HtaA, we incubated a 6×His-tagged HtaB protein with GST-HtaA that was prebound with hemin (holo-GST-HtaA). The His-HtaB protein was separated from holo-GST-HtaA by the use of metal affinity chromatography, and the absorbance values for His-HtaB and holo-GST-HtaA were determined for assessing hemin binding. The His-HtaB preparation that was incubated with holo-GST-HtaA showed a sharp increase in absorbance at 406 nm compared to His-HtaB that was not exposed to holo-GST-HtaA (Fig. 10A). In contrast, holo-GST-HtaA showed diminished absorbance at 406 nm compared to holo-GST-HtaA that was not mixed with His-HtaB (Fig. 10B). No cross-contaminating proteins were detected in the preparations used for UV-visual spectroscopy (Fig. 10C). These results indicate that HtaB is able to acquire hemin from holo-HtaA and further suggest that HtaB may function as an intermediate in a hemin relay system in which hemin is transferred initially from Hb to HtaA and then to HtaB.

Fig. 10.

HtaB acquires hemin from holo-HtaA. (A) Results of UV-visual scan of His-HtaB following incubation in the presence (+HtaA) or absence (−HtaA) of holo-GST-HtaA. (B) Results of UV-visual scan of holo-GST-HtaA after incubation in the presence (+HtaB) or absence (−HtaB) of His-HtaB. (C) Results of SDS-PAGE showing separation of His-HtaB from holo-GST-HtaA after incubation of the proteins. The results of a representative experiment are shown; experiments were performed at least three times with similar results.

DISCUSSION

In the last 10 years, hemin transport systems in several Gram-positive bacteria, including the important human pathogens S. aureus, S. pyogenes, B. anthracis, and C. diphtheriae, have been identified and characterized (6, 13, 26, 27). These uptake systems include ABC transporters and various cell wall or secreted proteins that are capable of binding hemin and/or hemoproteins such as hemoglobin or haptoglobin (1, 15, 26, 42). Surface proteins identified in these transporters contain examples of a novel class of hemin or Hb binding regions that are distinct from the binding motifs identified in hemin uptake proteins in Gram-negative organisms. Hemin binding proteins in species of Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Bacillus all contain heme binding NEAT domains, regions of approximately 125 amino acids that were originally identified in proteins associated with iron transport operons in Gram-positive bacteria (3, 26, 30, 31). The C. diphtheriae hmu heme transport gene cluster encodes the surface-exposed hemin binding proteins HtaA and HtaB. These proteins contain novel hemin binding domains that share no significant primary sequence similarity with any of the known hemin or Hb binding NEAT domains identified in other Gram-positive bacteria. We show in this report that HtaA possesses two hemin binding domains (CR1and CR2) and that HtaB contains a single CR. The CRs of HtaA and HtaB share relatively low sequence similarity, but all three regions contain several conserved residues, including two tyrosines and a histidine. The full-length HtaA protein as well as the individual CR1 and CR2 domains also bind Hb, as demonstrated using an ELISA-based system. HtaA exhibited the strongest binding to Hb, while CR2 showed more robust binding to Hb than the CR1 domain.

To identify residues that are important for hemin and Hb binding by HtaA and the CR subdomains, we performed site-directed mutagenesis using the various GST constructs of HtaA, CR1, and CR2. We showed that alanine substitutions in the CR domains at conserved residues Y361 (Y49 in CR1) and H412 (H107 in CR1) result in a significant reduction in the size of the Soret band at 406 nm in the presence of hemin, which suggests that one or both of these residues may have a critical function in coordination of the heme iron in the CR domains. Biochemical studies revealing more details, including crystal structure analysis, would likely be needed to clearly define the residues involved in coordinating the heme iron. Surprisingly, the mutations in the full-length GST-HtaA fusion (Y361, H412, and the Y361/Y412 double substitution) resulted in an increase in absorbance at 406 nm, suggesting an enhancement in hemin binding caused by these mutations. It is unclear why mutations in the CR2 region result in an apparent increase in hemin binding in the full-length HtaA protein whereas the same changes in GST-CR2 reduce hemin binding. It is possible that these mutations in the hemin binding region of CR2 increase the hemin binding efficiency of CR1 in the full-length HtaA protein, perhaps due to structural changes in the protein that result in a more favorable binding conformation in the CR1 region. This proposal is supported by the observation that the Y361A/Y49A double substitution, which affects both CR domains, virtually abolished hemin binding in GST-HtaA. It is also possible that the CR2 mutations result in hemin binding of greater efficiency at regions within HtaA other than the CR1 domain. It should be noted that the Y361A substitution in pKhtaA (pKhtaA-Y361A) abolished the ability of HtaA to use Hb and hemin as iron sources, suggesting that the enhanced hemin binding observed with GST-HtaA-Y361A does not contribute to the hemin iron utilization function of HtaA.

All of the amino acid changes that resulted in reduced hemin binding in the CR1 and CR2 domains strongly diminished Hb binding, providing further support for the idea that hemin and Hb share a binding region. The observation that CR2 exhibits stronger binding to Hb than either the CR1 domain or the HtaB-CR domain (which does not bind Hb) suggests that amino acid residues that are unique to the CR2 domain may be required for this enhanced Hb binding: it is also possible that overall structural differences between the CR domains, rather than specific amino acids, account for the differences in binding to Hb.

The results of the mutagenesis studies indicate that the Hb binding region in HtaA may include many of the same residues involved in hemin binding, suggesting that the Hb binding site(s) in HtaA is distinctly different from that described for other Hb binding proteins in Gram-positive bacteria. The observations of Hb binding in the NEAT domains of IsdB and IsdH showed that four adjacent residues, including invariant tyrosine and histidine residues, are critical for Hb binding (31). It was previously reported that S. aureus IsdA and B. anthracis IsdX1 not only bind to hemin but are able to bind immobilized Hb (10, 26). The IsdA and IsdX1 proteins contain a single NEAT domain that is typical of hemin binding domains in that it includes two conserved tyrosine resides separated by 3 amino acids; neither of these proteins has been reported to contain the aromatic amino acid cluster that is characteristic of the Hb binding region in IsdB and IsdH. Residues that are important for Hb binding in IsdA and IsdX1 have not been identified. The importance of the Hb binding detected in IsdA is not known, since results of hemin transfer experiments indicate that IsdA did not acquire hemin from Hb but did acquire hemin from the IsdB protein (48). However, IsdX1, which is a secreted protein, is able to extract hemin from Hb (26). The Shr protein from S. pyogenes was shown to bind Hb, although the interaction does not occur through the NEAT domain but was detected in an uncharacterized N-terminal region (30). Residues that are important in binding Hb or hemin in the Shr protein have not been reported.

In this report, we have shown that HtaA is able to acquire hemin from Hb; however, the mechanism of hemin transfer between Hb and HtaA has not been determined. The results of the mutagenesis studies indicate that the CR2 domain of HtaA binds Hb more effectively than CR1, suggesting that CR2 may function as the primary Hb binding region. The function of the CR1 domain in acquisition of hemin from Hb remains to be determined, although the Y49A mutation in CR1 resulted in a reduced ability to use Hb as an iron source, suggesting a possible function for this region in the acquisition of hemin from Hb. The Y361A mutation in the CR2 domain showed an even greater effect on the use of Hb as an iron source, possibly indicating a more significant role for this region. It has been proposed that, in other Gram-positive hemin uptake systems, acquisition of hemin from Hb initially involves the binding of Hb by a surface protein either at a NEAT domain, as in the case of IsdB, or in an undefined region, as observed with Shr (30). After Hb binding, hemin is extracted by an unknown mechanism and then transferred to a hemin binding NEAT domain either on the same protein or on a second protein, such as IsdA in S. aureus (31, 48). Whether a similar mechanism occurs in C. diphtheriae is not known; however, judging on the basis of our in vitro findings, it is possible that the CR2 domain serves as a primary Hb binding site, with CR1 serving as an accessory site that facilitates Hb binding. It should be noted that the two CR domains exhibited similar hemin binding characteristics, and it was previously shown that HtaB has an affinity for hemin similar to that of HtaA (1), suggesting that hemin binding is likely the primary function for HtaB.

While we have shown in this report that HtaB can acquire hemin from HtaA, we have not demonstrated binding between holo-HtaA and HtaB in the ELISA system utilized in this report (M. P. Schmitt, unpublished data). This observation suggests that any binding between HtaA and HtaB may be very weak or, alternatively, that the ELISA system may not be optimal for detecting an interaction between these proteins. It is also possible that the transfer of hemin from holo-HtaA to HtaB does not require protein binding but may occur through a natural diffusion process as proposed for other hemin binding proteins (28, 31). Natural diffusion of the hemin from Hb to HtaA may also occur. It was noted in the hemin transfer studies that Hb was not present in the Strep-HtaA elution fractions, suggesting that if Hb was binding to Strep-HtaA in these studies, it did not remain bound to Strep-HtaA at detectable levels following the washing steps.

The findings from the heme transfer studies and the Hb binding experiments lend support to a previously proposed model for hemin uptake in C. diphtheriae in which Hb is initially bound by HtaA at the cell surface. The hemin associated with Hb is acquired by HtaA and then transferred to HtaB or possibly to the HmuT hemin binding substrate protein. Although mutants encoded by htaB showed no defect in heme iron utilization, it is possible that htaB homologs, which are encoded in the chromosome of C. diphtheriae (18), compensate for its function. While these experiments provide the first evidence that hemin can be transferred from Hb to HtaA and from HtaA to HtaB, a more detailed biochemical analysis would be required to determine the precise mechanism for hemin acquisition and transport by HtaA and HtaB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jon Burgos and Scott Stibitz for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen C. E., Schmitt M. P. 2009. HtaA is an iron-regulated hemin binding protein involved in the utilization of heme iron in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Bacteriol. 191:2638–2648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altschul S. F., Warren G., Miller W., Meyers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andrade M. A., Ciccarelli F. D., Perez-Iratxeta C., Bork P. 15 August 2002, posting date NEAT: a domain duplicated in genes near the components of a putative Fe3+ siderophore transporter from Gram-positive bacteria. Genome Biol. 3:research0047-research0047.5. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-9-research0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anzaldi L. L., Skaar E. P. 2010. Overcoming the heme paradox: heme toxicity and tolerance in bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 78:4977–4989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ascoli F., Fanelli M. R., Antonini E. 1981. Preparation and properties of apohemoglobin and reconstituted hemoglobins. Methods Enzymol. 76:72–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bates C. S., Montanez G. E., Woods C. R., Vincent R. M., Eichenbaum Z. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes operon involved in binding of hemoproteins and acquisition of iron. Infect. Immun. 71:1042–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braun V. 2005. Bacterial iron transport related to virulence. Contrib. Microbiol. 12:210–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown J. S., Holden D. W. 2002. Iron acquisition by gram-positive bacterial pathogens. Microbes Infect. 4:1149–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cerdeño-Tárraga A. M., et al. 2003. The complete genome sequence and analysis of Corynebacterium diphtheriae NCTC13129. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:6516–6523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clarke S. R., Wiltshire M. D., Foster S. J. 2004. IsdA of Staphylococcus aureus is a broad spectrum iron-regulated adhesin. Mol. Microbiol. 51:1509–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collier R. J. 2001. Understanding the mode of action of diphtheria toxin: a perspective on progress during the 20th century. Toxicon 39:1793–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crosa J. H., Mey A. R., Payne S. M. (ed.). 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drazek E. S., Hammack C. A., Schmitt M. P. 2000. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from hemin and hemoglobin are homologous to ABC hemin transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 36:68–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fabian M., Solomaha E., Olson J. S., Maresso A. W. 2009. Heme transfer to the bacterial cell envelope occurs via a secreted hemophore in the gram-positive pathogen Bacillus anthracis. J. Biol. Chem. 284:32138–32146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher M., et al. 2008. Shr is a broad-spectrum surface receptor that contributes to adherence and virulence in group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 76:5006–5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grigg J. C., Vermeiren C. L., Heinrichs D. E., Murphy M. E. 2007. Haem recognition by a Staphylococcus aureus NEAT domain. Mol. Microbiol. 63:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henderson D. P., Payne S. M. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the Vibrio cholerae genes encoding the utilization of iron from haemin and haemoglobin. Mol. Microbiol. 7:461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kunkle C. A., Schmitt M. P. 2003. Analysis of the Corynebacterium diphtheriae DtxR regulon: identification of a putative siderophore synthesis and transport system that is similar to the Yersinia high-pathogenicity island-encoded yersiniabactin synthesis and uptake system. J. Bacteriol. 185:6826–6840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kunkle C. A., Schmitt M. P. 2005. Analysis of a DtxR-regulated iron transport and siderophore biosynthesis gene cluster in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Bacteriol. 187:422–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kunkle C. A., Schmitt M. P. 2007. Comparative analysis of hmuO function and expression in Corynebacterium species. J. Bacteriol. 189:3650–3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laemmli U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lei B., et al. 2002. Identification and characterization of a novel heme-associated cell surface protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4494–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Létoffé S., Ghigo J. M., Wandersman C. 1994. Iron acquisition from heme and hemoglobin by a Serratia marcescens extracellular protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:9876–9880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu M., Lei B. 2005. Heme transfer from streptococcal cell surface protein Shp to HtsA of transporter HtsABC. Infect. Immun. 73:5086–5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu M., et al. 2008. Direct hemin transfer from IsdA to IsdC in the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) heme acquisition system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 283:6668–6676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maresso A. W., Garufi G., Schneewind O. 2008. Bacillus anthracis secretes proteins that mediate heme acquisition from hemoglobin. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazmanian S. K., et al. 2003. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299:906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mocny J. C., Olson J. S., Connell T. D. 2007. Passively released heme from hemoglobin and myoglobin is a potential source of nutrient iron for Bordetella bronchiseptica. Infect. Immun. 75:4857–4866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Otto B. R., Vught V.-V., Verweij-van Vught A. M., MacLaren D. M. 1992. Transferrins and heme compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 18:217–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ouattara M., et al. 2010. Shr of group A streptococcus is a new type of composite NEAT protein involved in sequestering haem from methemoglobin. Mol. Microbiol. 78:739–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pilpa R. M., et al. 2009. Functionally distinct NEAT (NEAr Transporter) domains within the Staphylococcus aureus IsdH/HarA protein extract heme from methemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 284:1166–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Popovic T., et al. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of diphtheria in Russia, 1985–1994. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1064–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schmitt M. P. 1997. Utilization of host iron sources by Corynebacterium diphtheriae: identification of a gene whose product is homologous to eukaryotic heme oxygenase and is required for acquisition of iron from heme and hemoglobin. J. Bacteriol. 179:838–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmitt M. P. 1997. Transcription of the Corynebacterium diphtheriae hmuO gene is regulated by iron and heme. Infect. Immun. 65:4634–4641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmitt M. P. 2004. Corynebacterium diphtheriae, p. 344–359 In Crosa Jorge H., Mey Alexandra R., Payne Shelley M. (ed.), Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmitt M. P., Drazek E. S. 2001. Construction and consequences of directed mutations affecting the hemin receptor in pathogenic Corynebacterium species. J. Bacteriol. 183:1476–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Skaar E. P., Gaspar A. H., Schneewind O. 2004. IsdG and IsdI, heme-degrading enzymes in the cytoplasm of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 279:436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stojiljkovic I., Hantke K. 1994. Transport of hemin across the cytoplasmic membrane through a hemin-specific periplasmic binding-protein-dependent transport system in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 13:719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stojiljkovic I., Perkins-Balding D. 2002. Processing of heme and heme-containing proteins by bacteria. DNA Cell Biol. 21:281–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stugard C. E., Daskaleros P. A., Payne S. M. 1989. A 101-kilodalton heme-binding protein associated with Congo Red binding and virulence of Shigella flexneri and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli strains. Infect. Immun. 57:3534–3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tai S.-P., Krafft A. E., Nootheti P., Holmes R. K. 1990. Coordinate regulation of siderophore and diphtheria toxin production by iron in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Microb. Pathog. 9:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tarlovsky Y., et al. 2010. A Bacillus anthracis S-layer homology protein that binds heme and mediates heme delivery to IsdC. J. Bacteriol. 192:3503–3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Torres V. J., Pishchany G., Humayun M., Schneewind O., Skaar E. P. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus IsdB is a hemoglobin receptor required for heme iron utilization. J. Bacteriol. 188:8421–8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Umbreit J. 2007. Methemoglobin—it's not just blue: a concise review. Am. J. Hematol. 82:134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilks A., Schmitt M. P. 1998. Expression and characterization of a heme oxygenase (HmuO) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:837–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Winkelmann G. 2002. Microbial siderophore-mediated transport. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30:691–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhu H., Liu M., Lei B. 2008. The surface protein Shr of Streptococcus pyogenes binds heme and transfers it to the streptococcal heme-binding protein Shp. BMC Microbiol. 8:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhu, et al. 2008. Pathway for heme uptake from human methemoglobin by the iron-regulated surface determinants (Isd) system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 283:18450–18460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]