Abstract

In order to better characterize the initial stages of sporulation past Spo0A activation and the associated solventogenesis in the important industrial and model organism Clostridium acetobutylicum, the spoIIE gene was successfully disrupted and its expression was silenced. By silencing spoIIE, sporulation was blocked prior to asymmetric division, and no mature spores or any distinguishable morphogenetic changes developed. Upon plasmid-based complementation of spoIIE, sporulation was restored, although the number of spores formed was below that of the plasmid control strain. To investigate the impact of silencing spoIIE on the regulation of sporulation, transcript levels of sigF, sigE, and sigG were examined by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR, and the corresponding σF, σE, and σG protein levels were determined by Western analysis. Expression of sigF was significantly reduced in the inactivation strain, and this resulted in very low σF protein levels. Expression of sigE was barely detected, and no sigG transcript was detected at all; consequently, no σE or σG proteins were detected. These data suggest an autostimulatory role for σF in C. acetobutylicum, in contrast to the model organism for endospore formation, Bacillus subtilis, and confirm that high-level expression of σF is required for expression of σE and σG. Unlike the σF and σE inactivation strains, the SpoIIE inactivation strain did not exhibit inoculum-dependent solvent formation and produced good levels of solvents from both exponential- and stationary-phase inocula. Thus, we concluded that SpoIIE does not control solvent formation.

INTRODUCTION

Clostridia are an ancient, diverse class and genus of anaerobic, endospore-forming bacteria, ranging from pathogenic to solventogenic and cellulolytic species (34). The process of clostridial endospore formation is still poorly understood, and this has hindered progress in understanding their physiology and their pathophysiological impact and devising strategies to engineer strains for industrial applications (25, 33). Understanding how the sporulation process is initiated, propagated, and sustained is especially important in Clostridium acetobutylicum, where both sporulation and solvent formation are transcriptionally activated by Spo0A, the master transcription factor of sporulation (14). Although C. acetobutylicum has not been widely used industrially for its acetone, butanol, and ethanol (ABE) fermentation for several decades (19), interest in this and related organisms has intensified recently because of their potential to produce not only butanol as a chemical and biofuel (25, 33) but also butyrate as an industrial chemical and biofuel precursor (33).

It is still broadly assumed that the regulation of sporulation in clostridia is similar to that in the model organism for endospore formation, Bacillus subtilis. In B. subtilis, sporulation is regulated by a cascade of different transcription/sigma factors, starting with Spo0A and followed by the prespore-specific sigma factor σF and the mother cell-specific σE (16). In the prespore, σF expression is followed by σG expression, and in the mother cell, σE expression is followed by σK expression (16). Expression and activation of each of these sigma factors are tightly controlled and generally subject to both transcriptional and posttranslational control (16). The gene sigF, encoding the first sigma factor to become active (σF), is part of a tricistronic operon with spoIIAA and spoIIAB (10, 36) and is upregulated by phosphorylated Spo0A (Spo0A∼P) (45, 46). Though translated, σF is kept inactive by being sequestered by SpoIIAB until after asymmetric division (37). Following asymmetric division, the anti-anti-sigma factor SpoIIAA is dephosphorylated by the membrane-bound phosphatase SpoIIE and the dephosphorylated SpoIIAA binds to SpoIIAB to release σF (2, 8, 23). In addition to its role in activating σF, SpoIIE also plays a key role in asymmetric division. SpoIIE has been found to directly interact with FtsZ (6, 22, 26, 28), a tubulin-like protein, and this interaction, along with an increase in FtsZ protein levels, results in the repositioning of the FtsZ ring from the center of the cell to a ring at each pole of the cell, where one of the rings eventually forms the asymmetric septum (6, 9). It is through these two roles, helping to position the asymmetric FtsZ ring and releasing (and thus activating) σF from SpoIIAB, that SpoIIE plays an essential part in the sporulation process of B. subtilis.

The C. acetobutylicum homolog of spoIIE has been identified and annotated (31), and its expression has been confirmed (1, 20). Expression of spoIIE is initiated during early stationary phase and reaches its peak shortly thereafter (20). This profile generally matches with the promoter activity of spoIIE in B. subtilis, where activity begins during early stationary phase and continues into mid-stationary phase (11). However, when a similar promoter activity study was performed on spoIIE in C. acetobutylicum, activity was not noted until mid-stationary phase, with a peak in expression soon after that (38). In order to investigate the role of spoIIE in sporulation and solventogenesis, the gene was downregulated using antisense RNA (38). Upon knockdown of spoIIE, solventogenesis in the strain was slightly prolonged, and sporulation was significantly delayed compared to a plasmid control strain (38).

In B. subtilis, strains with mutations in spoIIE had similar phenotypes to sigF and sigE mutants, in that sporulation was blocked at stage II (asymmetric division) and that disporic cells developed (17). The asymmetric septa that formed were thick septal structures, like those generally seen during vegetative growth, and not the thinner septal structures typically seen during sporulation (5). In contrast to the B. subtilis sigF and sigE mutants, sporulation was blocked prior to asymmetric division in C. acetobutylicum mutants FKO1 and EKO1 with silenced sigF (21) and sigE (43) genes, respectively. If SpoIIE plays a similar role in sporulation in C. acetobutylicum as in B. subtilis, a similar phenotype as the FKO1 mutant would be expected, since σF would not become active. In order to test this hypothesis, the spoIIE gene was inactivated and the resulting strain was characterized. We found that, like FKO1, sporulation was blocked prior to asymmetric division and that expression of σF, σE, and σG was severely reduced or eliminated altogether. The inactivation strain was successfully complemented using plasmid expression (a process that has proved unsuccessful in the sigF, sigE, and sigG inactivation strains of C. acetobutylicum [21, 43]) to reinstate sporulation and expression of all three sigma factors. Solvent formation in both the spoIIE inactivation strain and the complemented strain was also examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and maintenance conditions.

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, along with their relevant properties. Strains were grown and maintained as described in reference 43.

Analytical methods.

Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical A600 with a DU 730 spectrophotometer (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA). Culture supernatant samples were analyzed for glucose, acetate, acetoin, ethanol, butyrate, acetone, and butanol with an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) high-performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) (41). DNA concentrations and purities were measured with a NanoDrop (Wilmington, DE) spectrophotometer.

Bacterial transformations.

A Gene Pulser Xcell electroporation system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to transform both Escherichia coli and C. acetobutylicum. Prior to transformation into C. acetobutylicum, plasmids were methylated in E. coli carrying the methylating plasmid pAN2, a plasmid in which the tetracycline and ampicillin resistance cassettes in pAN1 (29) were replaced with a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, and clostridial transformations were performed as described in reference 30.

Construction of disruption and complementation plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and the primers used are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. To disrupt the spoIIE gene (CAC3205), the plasmid pKOSPOIIE was constructed. First, a 587-bp region of the spoIIE gene was PCR amplified with AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) from C. acetobutylicum genomic DNA using the primer set spoIIE-frag-F/R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), and the product was cloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPOTA cloning plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and One Shot TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting plasmid is called pCR8-SPOIIE. This plasmid was then linearized with DraI (New England BioLabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA), which has a single digestion site approximately in the middle of the spoIIE fragment, and the ends were dephosphorylated with Antarctic phosphatase (NEB, Ipswich, MA). A chloramphenicol/thiamphenicol resistance (Cm/Thr) cassette optimized for C. acetobutylicum (39) was ligated into pCR8-SPOIIE using a Quick Ligation kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA) and cloned into One Shot TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting plasmid is called pCR8-SpoIIE/CM. The Cm/Thr cassette encodes chloramphenicol resistance in E. coli and thiamphenicol resistance in C. acetobutylicum. Finally, the SPOIIE/CM gene disruption cassette was recombined into the Destination vector pKOREC (43) using Invitrogen's Gateway system (Carlsbad, CA). The resulting plasmid is called pKOSPOIIE.

To complement the disruption strain, the plasmid pSPOIIE was constructed. The entire spoIIE gene with its full upstream and downstream intergenic regions was amplified from C. acetobutylicum genomic DNA using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnymes Oy, Espoo, Finland) and the primer set spoIIE-F/R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR product was then cloned into the pCR8/GW/TOPOTA cloning plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and One Shot TOP10 E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. This plasmid, pCR8-FULL-SPOIIE, was then recombined into the pDEST-TC Destination plasmid using the Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) Gateway LR recombination reaction to yield pSPOIIE. pDEST-TC was constructed by first linearizing the tetracycline-based plasmid pTLH1 (13) with PvuII (NEB, Ipswich, MA). This linearized plasmid was then dephosphorylated, ligated to a phosphorylated Destination cassette from pcDNA-DEST40 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and cloned into DB3.1 ccdB resistant E. coli cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Tetracycline was used only with solid agar plates because of the negative effects on clostridial growth and metabolism in liquid media (12).

Inducing and confirming chromosomal integration.

Chromosomal integration of pKOSPOIIE was achieved using a similar protocol as described in reference 43. C. acetobutylicum pKOSPOIIE was grown to mid-exponential phase, and 150 μl of culture was plated onto solid 2× YTG plates (32) supplemented with 5 μg/ml thiamphenicol (Th). After 24 h of growth, colonies were vegetatively transferred onto fresh 2× YTG plates with 5 μg/ml of thiamphenicol every 24 h for a total of six transfers. Colonies were then plated onto fresh 2× YTG plates with no antibiotic and vegetatively transferred every 24 h for a total of four transfers in order to cure the cells of the plasmid. Colonies were then transferred onto 2× YTG plates with 5 μg/ml of thiamphenicol and onto 2× YTG plates with 40 μg/ml of erythromycin, and putative integrants were determined as described in reference 43. Though a double-crossover event was preferred, only single-crossover events were found in the screening process, similar to past studies using this protocol (21, 43). Finally, colony PCR (39) was used to determine through which region of homology integration was achieved.

Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNA from wild type (WT) and the spoIIE mutant (SPOIIEKO) was isolated using Qiagen's Genomic-tip 100/G system (Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Following digestion, 500 ng of genomic DNA and 1 ng of plasmid DNA were loaded onto the gel and separated by gel electrophoresis. Blots were prepared, probed, and imaged as described in reference 43. Probe template was generated from WT genomic DNA using the primers SpoIIE-probe-F/R (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnymes Oy, Espoo, Finland). Probes were then biotinylated using the NEBlot Phototope kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA), following the manufacturer's instruction.

RNA isolation and semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Cells were sampled and RNA was isolated as described in reference 20. RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA as described in reference 7, except that 700 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed. Primers were designed to amplify the mature, full transcript and are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. All products were amplified using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Western blot analysis.

Crude cell extracts were prepared and total protein concentration was determined as described in reference 43. For Western blots, 50 μg of total protein was loaded onto the gels, and blots were prepared and imaged as described in reference 43. Primary antibodies (affinity-purified, polyclonal antibodies custom-made by ProteinTech [Chicago, IL] in rabbits) were diluted to the following: Spo0A, 1:2,000; σF, 1:250; σE, 1:250; and σG, 1:250. Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase conjugated [Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA]) were diluted to 1:3,000. All antibodies were incubated with the membrane for 1 h at room temperature, except for the antibody against σE, which was incubated overnight at 4°C.

Sporulation assays.

Heat shock and chloroform spore assays were performed as described in reference 43.

Microscopy.

Phase-contrast microscopy samples were prepared as described in reference 42 and were imaged on a Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) Axioskop 2 microscope. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples were prepared and imaged as described in reference 20.

RESULTS

Integration of pKOSPOIIE to disrupt spoIIE.

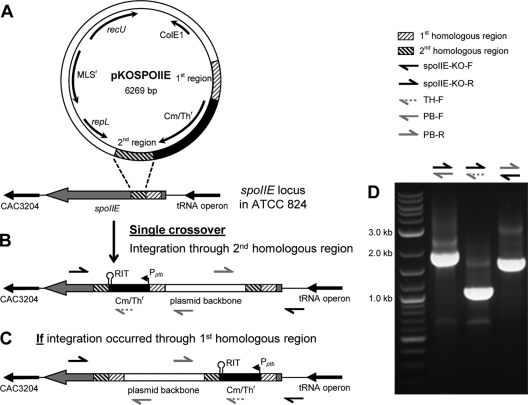

The phosphatase spoIIE (CAC3205) (31) was disrupted using a replicating plasmid with two regions of homology (the 1st region being 294 bp long and the 2nd region being 293 bp long) (Fig. 1A), similar to the approaches used to disrupt sigF (21) and sigE and sigG (43). Though a double-crossover event was desired (to obtain colonies resistant to thiamphenicol but sensitive to erythromycin), only single-integration mutants (colonies resistant to both thiamphenicol and erythromycin) were detected in the screening, similar to previous attempts using comparable plasmids (21, 43). In order to determine whether the single integration occurred through the 1st or 2nd homologous region, the following five primers were used: spoIIE-KO-F, spoIIE-KO-R, TH-F, PB-F, and PB-R (Fig. 1; see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Putative integration colonies, from here on referred to as SPOIIEKO, were selected for colony PCR (39) using the primer sets PB-F/spoIIE-KO-R, TH-F/spoIIE-KO-R, and spoIIE-KO-F/PB-R (Fig. 1). If integration occurred through the 1st homologous region, the three PCR primer sets would have produced bands of 998 bp, 6,308 bp, and 2,840 bp, respectively (Fig. 1C), while if the integration occurred through the 2nd homologous region, the products would have been 2,046 bp, 1,088 bp, and 1,791 bp, respectively (Fig. 1B). Following amplification, bands corresponding to integration through the 2nd region were produced (Fig. 1D). In addition, the entire integration region was PCR amplified and sequenced. The integration region could not be amplified as a whole, but overlapping regions were amplified and sequenced (data not shown). The sequencing results confirmed that a single copy of pKOSPOIIE integrated through the 2nd homologous region.

Fig. 1.

Disruption of the spoIIE gene. (A) The pKOSPOIIE vector and the spoIIE locus on the C. acetobutylicum ATCC 824 genome. The two regions of homology are indicated on both the plasmid and the chromosome. (B) Integration of pKOSPOIIE into the genome. The plasmid underwent a single crossover through the 2nd homologous region. The locations of the confirmation primers along with the promoter (Pptb) (44) and rho-independent terminator (RIT) of the Cm/Thr cassette are indicated. (C) Schematic of how pKOSPOIIE would have integrated had a single crossover through the 1st homologous region occurred. The locations of the confirmation primers are indicated. (D) PCR results for the confirmation primers used on SPOIIEKO. The sizes demonstrate that pKOSPOIIE integrated by a single crossover through the 2nd region of homology.

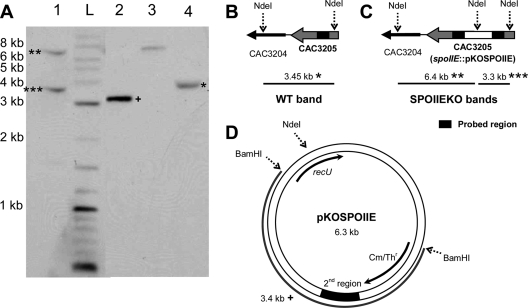

Furthermore, genomic DNA from both WT and SPOIIEKO C. acetobutylicum was prepared for Southern blotting to demonstrate that pKOSPOIIE integrated only within the spoIIE locus. Genomic DNA from both strains was digested with NdeI. This restriction enzyme has two digestion sites flanking the spoIIE locus (Fig. 2B) and a single digestion site on the plasmid backbone (Fig. 2D). After hybridization with the probe, a single band (3.45 kb) should be produced from digested WT genomic DNA, while two bands (6.4 kb and 3.3 kb) should be produced from digested SPOIIEKO genomic DNA. NdeI- and BamHI-digested pKOSPOIIE was also prepared (Fig. 1D) and probed as positive controls and size markers. The NdeI-digested plasmid is 6.3 kb, about the same size as the upper band for SPOIIEKO genomic DNA, while the BamHI-digested plasmid produces a 3.4-kb fragment, about the same size as the lower SPOIIEKO band and the WT band. Only two bands were detected for the disruption strain, and their sizes were about what was expected (∼6.4 kb and ∼3.3 kb) (Fig. 1A). This confirms that pKOSPOIIE integrated only within the spoIIE locus and not within any other loci on the chromosome.

Fig. 2.

Southern blot confirmation of pKOSPOIIE integration site. (A) NdeI-digested genomic DNA from C. acetobutylicum WT and SPOIIEKO hybridized with a probe for the 2nd homologous region. Lane 1, NdeI-digested SPOIIEKO DNA; lane 2, BamHI-digested pKOSPOIIE; lane 3, NdeI-digested pKOSPOIIE; lane 4, NdeI-digested WT DNA; lane L, 2-log ladder from NEB. Membrane was exposed for 2 min. Diagrams of expected bands from WT (B), SPOIIEKO (C), and pKOSPOIIE (D) are shown.

Silencing of spoIIE significantly reduces the expression of sigF and prevents the expression of sigE and sigG.

In the absence of an antibody against SpoIIE, semiquantitative RT-PCR was used to prove that expression of spoIIE is silenced by the integration of pKOSPOIIE. RNA was isolated from WT and SPOIIEKO cultures after 48 h of growth (growth profiles are displayed in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and reverse transcribed into cDNA. Primers were designed to amplify a 1,812-bp fragment of the full transcript, which spans the site of disruption. Following amplification, a band was detected for WT, but no bands were detected for SPOIIEKO (Fig. 3A). A biological replicate produced the same results (data not shown). As a positive control, a 622-bp fragment of the full spo0A transcript was also amplified and was detected in both WT and SPOIIEKO (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Expression of spoIIE and sporulation-related transcriptional regulators in C. acetobutylicum WT, SPOIIEKO, and SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE). (A) Semiquantitative RT-PCR of spoIIE, spo0A, sigF, sigE, and sigG in WT, SPOIIEKO, and SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE). Transcript expression was tested at 48 h after inoculation. +, reactions in which reverse transcriptase was added to the reaction mixture; −, reactions in which reverse transcriptase was not included in the reaction mixture. Products were imaged on an ethidium bromide-stained 1% agarose gel. (B) Western blot analysis of Spo0A, σF, σE, and σG in WT, SPOIIEKO, and SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE). The σF image with an asterisk to the right was exposed for twice as long as the image above it.

Next, the expression of three of the major sporulation-related sigma factors, σF, σE, and σG, was investigated in WT and SPOIIEKO cultures. First, mRNA expression was examined using semiquantitative RT-PCR. A sigF band was detected in SPOIIEKO, but its intensity was significantly lower than that in WT, while a sigE band was barely detected in SPOIIEKO (Fig. 3A). No sigG band was detected in SPOIIEKO. Next, the protein expression of these same three sigma factors was tested. Though a σF band was detected, it was a very weak band, and no bands were detected for either σE or σG (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that silencing of spoIIE in SPOIIEKO affects the expression of the sporulation-related sigma factors σF, σE, and σG.

Sporulation and all morphological changes are abolished in SPOIIEKO.

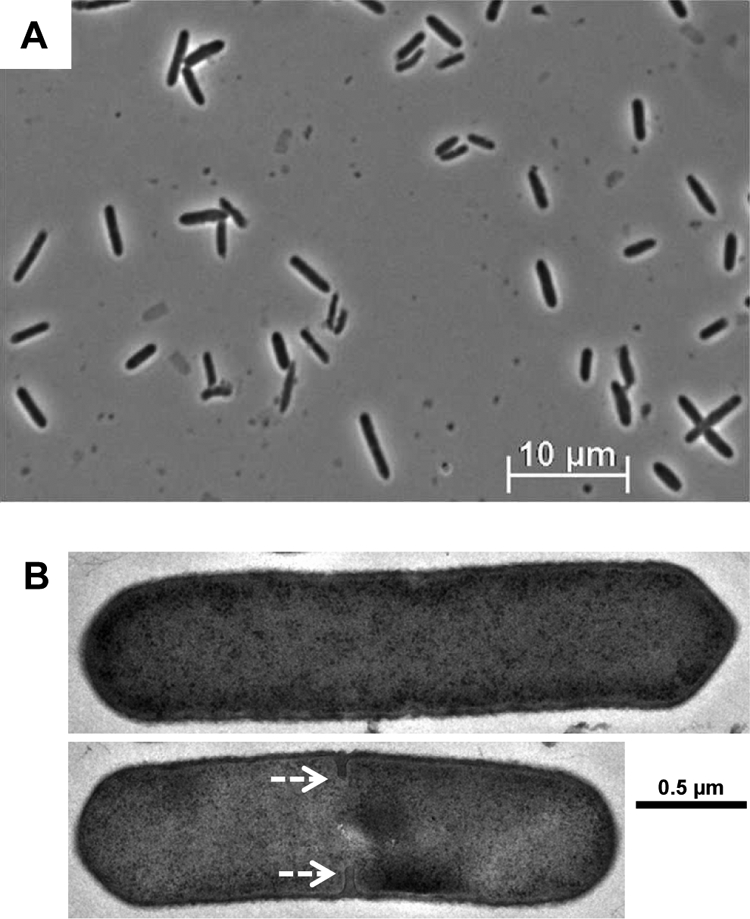

Previously, when the sigF or sigE genes were disrupted and inactivated, the corresponding strains, FKO1 (21) and EKO1 (43), respectively, showed very few signs of differentiation and neither formed mature spores. For both strains, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed slight electron-translucent regions at one or both poles of the cell (21, 43), and the EKO1 strain produced one or more internal, longitudinal membranes (43). Therefore, with the very weak expression of σF and the lack of σE (Fig. 3B), it was not expected that SPOIIEKO would display many, if any, signs of differentiation. Phase-contrast microscopy images after 72 h of growth show only rod-shaped, exponential-phase-like cells with no differentiation forms, such as clostridial or endospore forms (18, 27, 42), detected (Fig. 4A). The cells were further examined under TEM, and again, only rod-shaped cells with no defining internal structures were found (Fig. 4B), in contrast to the FKO1 (21) and EKO1 (43) strains. Interestingly, even though cells were within mid-stationary phase, some dividing cells with a septum developing in the middle of the cell were still detected (Fig. 4B). However, no asymmetric division was visible in any of the cells imaged. Finally, when late-stationary-phase cultures (>5 days old) were submitted to either chloroform treatment or heat treatment, no colonies survived, verifying that SPOIIEKO does not produce mature spores. In contrast, WT cultures generally produce at least 1 × 105 CFU/ml of spores by day 5.

Fig. 4.

Microscopy of C. acetobutylicum SPOIIEKO after 72 h of growth. (A) Phase-contrast microscopy of SPOIIEKO. Only rod-shaped cells with no identifiable differentiation phenotypes are evident. (B) TEM of SPOIIEKO. White, dashed arrows indicate the developing symmetrical septal membrane.

Plasmid-based complementation of strain SPOIIEKO restores sporulation.

In order to complement the SPOIIEKO strain, we constructed plasmid pSPOIIE. The spoIIE gene along with the full upstream and downstream intergenic regions was cloned into a tetracycline-based backbone. Presumably, the upstream region includes the promoter and ribosomal binding site for spoIIE and any other regulatory elements, and the downstream region should contain a transcriptional terminator, though no stem-loop structure was found downstream of spoIIE (24). In the complemented strain, SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE), expression of spoIIE mRNA was restored to WT levels, as were the mRNA and protein levels of all three of the tested sigma factors, σF, σE, and σG (Fig. 3).

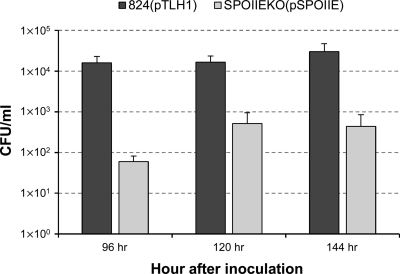

The strain was also able to produce mature spores, although to a lesser extent than the plasmid control strain 824(pTLH1) (Fig. 5). 824(pTLH1) produced over 1 × 104 CFU/ml of spores by 96 h (4 days), while the complemented strain SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE) produced only about 5 × 102 CFU/ml by 120 h (5 days) (Fig. 5). Though production was significantly lower than the plasmid control, SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE) was still able to produce mature spores, which the strain SPOIIEKO failed to do. It is significant to note that previous attempts to complement sporulation-related genes in C. acetobutylicum (notably, sigF, sigE, and sigG) with multicopy plasmids were not successful (21, 43). Also, the plasmid control strain 824(pTLH1) itself produces fewer spores than typical WT cultures, which produce at least 1 × 105 CFU/ml of spores by 120 h (5 days) of growth (21). Previous plasmid control strains would generally sporulate to a greater extent than WT (42), though it is unknown why this occurs, but this particular plasmid control with the tetracycline resistance gene has not been tested for sporulation before.

Fig. 5.

Sporulation of complemented strain SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE). The numbers of CFU of the plasmid control strain 824(pTLH1) and the complemented strain SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE) are shown. Standard deviations between two biological replicates and two technical replicates (n = 4) are indicated.

Silencing of spoIIE does not abolish solvent production, which remains independent of the inoculum age.

When the master sporulation transcription factor Spo0A was inactivated, solvent production was virtually abolished because Spo0A directly upregulates a number of important solvent-formation genes (14). When the early-acting sigma factors σF and σE were inactivated (strains FKO1 and EKO1, respectively), solvent production was found to be dependent upon the age of the inoculum used (21, 43). When mid- to late-exponential cultures were used as inocula, the levels of solvents produced were significantly lower than typical WT levels, but when a stationary-phase culture was used, solvent levels returned to WT levels (21, 43). Since the phenotype of SPOIIEKO was similar to the phenotypes of FKO1 and EKO1, a similar inoculum dependency in solvent formation was expected. However, no inoculum dependency was found in SPOIIEKO (Table 1). When either an exponential-phase or stationary-phase culture was used for the inoculum, the cultures produced similar amounts of butanol (∼130 mM), acetone (∼50 mM), and ethanol (∼20 mM), though these levels are slightly lower than WT levels (Table 1). The SPOIIEKO strain produced higher levels of acetoin and consumed smaller amounts of glucose, possibly due to the premature culture termination due to accumulation of higher levels of butyrate. The complementation strain SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE) produced normal levels of solvents without any inoculum-age dependency (Table 1). Overall, SpoIIE does not have a significant impact on solvent production, although it appears to impact glucose utilization in these simple batch cultures without pH control.

Table 1.

Endpoint metabolite concentrations after 120 h of growth

| Strain | Phase of inoculum used | Endpoint metabolite concn (mM)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumed glucose | Butyrate | Acetate | Acetoin | Ethanol | Acetone | Butanol | ||

| WT | Exponential (n = 6) | 413.2 (±18.9) | 11.9 (±1.8) | 0.5 (±0.8) | 16.7 (±0.8) | 29.8 (±3.0) | 77.1 (±11.2) | 181.6 (±7.9) |

| WT | Stationary (n = 6) | 403.0 (±9.8) | 13.1 (±1.3) | 0.1 (±0.2) | 16.6 (±0.8) | 28.2 (±1.7) | 86.4 (±12.4) | 182.1 (±7.0) |

| SPOIIEKO | Exponential (n = 6) | 321.2 (±8.9) | 24.0 (±5.2) | 1.9 (±1.9) | 38.4 (±3.4) | 20.4 (±1.0) | 50.7 (±8.7) | 130.4 (±9.9) |

| SPOIIEKO | Stationary (n = 6) | 311.8 (±23.4) | 28.3 (±5.6) | 3.7 (±4.9) | 36.2 (±5.3) | 21.4 (±2.6) | 50.8 (±4.9) | 127.7 (±10.3) |

| pTLH1 | Exponential (n = 2) | 311.0 (±16.4) | 18.8 (±2.1) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 26.3 (±13.1) | 25.5 (±0.1) | 77.2 (±5.9) | 165.1 (±6.7) |

| SPOIIEKO(pSPOIIE) | Exponential (n = 2) | 330.9 (±8.1) | 16.3 (±4.6) | 0.6 (±2.1) | 27.4 (±10.4) | 29.9 (±7.0) | 82.0 (±13.4) | 175.1 (±1.9) |

Values in parentheses show standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the role of SpoIIE in the sporulation process of C. acetobutylicum was investigated by disrupting and inactivating its gene, spoIIE. In the inactivation strain SPOIIEKO, expression of spoIIE was silenced, as expected, but surprisingly, expression of sigF and its resulting protein, σF, was also significantly reduced (Fig. 3). In addition, very little sigE transcript was detected, resulting in no protein detection, and no sigG transcript or protein was detected (Fig. 3). These results further support the finding from the sigF inactivation strain FKO1 that expression of σE and σG is dependent upon expression of σF (21). Although low levels of σF were detected, these appear not to be sufficient to express σE or σG.

As stated, the decreased expression of sigF itself in SPOIIEKO was not expected. In B. subtilis, SpoIIE plays two key roles in sporulation. The first is during asymmetric division, where it interacts with FtsZ and plays a role in the repositioning of the FtsZ ring around the poles of the cell (6, 9), and the second is by activating σF by dephosphorylating SpoIIAA (2, 8, 23). In neither of these roles should SpoIIE affect the expression of the sigF transcript. After conducting a thorough literature search, a study investigating the expression of sigF in a SpoIIE inactivation B. subtilis mutant could not be identified. A possible explanation for the observation that inactivation of SpoIIE affects the transcription of sigF is that, in C. acetobutylicum, σF may stimulate its own expression. On the basis of microarray analysis, it has been shown that sigF is upregulated by Spo0A in C. acetobutylicum (40) and that sigF undergoes a bimodal expression pattern (20). Our hypothesis is that Spo0A∼P initially upregulates the sigF operon, including the regulators spoIIAA and spoIIAB, and the σF protein from this initial expression of sigF is sequestered by SpoIIAB, like in the B. subtilis model (37). Also like in the B. subtilis model, SpoIIE then dephosphorylates SpoIIAA so that it can bind to SpoIIAB and release σF (2, 8, 23). The released and active σF would then go on to further upregulate the sigF operon, and this would result in the bimodal shape of its expression pattern (20). Without these higher levels of σF, expression of σE and σG is not possible, and without σE expression, sporulation is blocked prior to asymmetric division, as in the sigE inactivation strain (43). This hypothesis is further supported by the prediction of a σF/G-binding motif (a motif recognized by both σF and σG) upstream of the sigF operon (35), though this has not been experimentally validated.

Complementation of spoIIE restored sporulation in SPOIIEKO (Fig. 5), but the level of sporulation was significantly lower than that for the plasmid control. A possible explanation for these lower levels, though doubtful, is polar effects due to the disruption. CAC3204, the gene downstream of spoIIE, is annotated as a cell cycle protein (31), but it is not predicted to be part of an operon with spoIIE (35). Instead, spoIIE in C. acetobutylicum is predicted to be transcribed as a singleton and not part of an operon (35), like spoIIE in B. subtilis (11). A putative σA-binding motif was found upstream of both spoIIE and CAC3204 (35), and these promoter regions were unaffected by the disruption (Fig. 1B). A rho-independent terminator was not found between spoIIE and CAC3204 (24), but neither is one found downstream of the spoIIE gene in B. subtilis (24). Finally, though the Pptb promoter of the Cm/Thr cassette is a strong promoter, the rho-independent terminator at the end of the cassette should prevent read-through into CAC3204 (Fig. 1B).

In contrast to both the sigF and sigE inactivation strains FKO1 (21) and EKO1 (43), SPOIIEKO did not display an inoculum dependency on its ability to produce solvents (Table 1). Though the solvent levels were slightly lower than WT levels, the strain produced solvents when inoculated with either exponentially growing cells or stationary-phase cells (Table 1). So far, the only strains which display an inoculum dependency on solvent formation are FKO1 and EKO1, and the reason for this is unknown.

What remains unknown about the role of SpoIIE in sporulation in C. acetobutylicum is its location within the cell and what, if any, role it plays in asymmetric division. In B. subtilis, SpoIIE is a membrane-bound enzyme and is located within the septal membrane (3, 4). However, if SpoIIE must activate σF prior to asymmetric division in C. acetobutylicum, it is unknown where it would be located within the cell. If the hypothesis that SpoIIE is active prior to asymmetric division is true, this activity would have a profound impact on the C. acetobutylicum model for sporulation. Instead of being a prespore-specific sigma factor, as in B. subtilis, σF could be active throughout the predivisional cell and may have roles beyond just sporulation. Because this hypothesis is in stark contrast to the B. subtilis model, more experimental evidence is needed to support it, but as has been seen in C. perfringens (15), sporulation in clostridia may be a substantially different process than sporulation in bacilli.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the use of the Delaware Biotechnology Institute Bio-Imaging Facility for all microscopy images, and we thank Shannon Modla for preparing and imaging the electron microscopy images.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant CBET-0853490.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 22 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alsaker K. V., Papoutsakis E. T. 2005. Transcriptional program of early sporulation and stationary-phase events in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 187:7103–7118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arigoni F., Duncan L., Alper S., Losick R., Stragier P. 1996. SpoIIE governs the phosphorylation state of a protein regulating transcription factor sigma F during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:3238–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arigoni F., Pogliano K., Webb C. D., Stragier P., Losick R. 1995. Localization of protein implicated in establishment of cell type to sites of asymmetric division. Science 270:637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barak I., et al. 1996. Structure and function of the Bacillus SpoIIE protein and its localization to sites of sporulation septum assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1047–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barak I., Youngman P. 1996. SpoIIE mutants of Bacillus subtilis comprise two distinct phenotypic classes consistent with a dual functional role for the SpoIIE protein. J. Bacteriol. 178:4984–4989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ben-Yehuda S., Losick R. 2002. Asymmetric cell division in B. subtilis involves a spiral-like intermediate of the cytokinetic protein FtsZ. Cell 109:257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borden J. R., Jones S. W., Indurthi D., Chen Y., Papoutsakis E. T. 2010. A genomic-library based discovery of a novel, possibly synthetic, acid-tolerance mechanism in Clostridium acetobutylicum involving non-coding RNAs and rRNA processing. Metab. Eng. 12:268–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duncan L., Alper S., Arigoni F., Losick R., Stragier P. 1995. Activation of cell-specific transcription by a serine phosphatase at the site of asymmetric division. Science 270:641–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Errington J. 2003. Regulation of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fort P., Piggot P. J. 1984. Nucleotide sequence of sporulation locus spoIIA in Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:2147–2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guzman P., Westpheling J., Youngman P. 1988. Characterization of the promoter region of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIE operon. J. Bacteriol. 170:1598–1609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris L. M., Blank L., Desai R. P., Welker N. E., Papoutsakis E. T. 2001. Fermentation characterization and flux analysis of recombinant strains of Clostridium acetobutylicum with an inactivated solR gene. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27:322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris L. M., Desai R. P., Welker N. E., Papoutsakis E. T. 2000. Characterization of recombinant strains of the Clostridium acetobutylicum butyrate kinase inactivation mutant: need for new phenomenological models for solventogenesis and butanol inhibition? Biotechnol. Bioeng. 67:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris L. M., Welker N. E., Papoutsakis E. T. 2002. Northern, morphological, and fermentation analysis of spo0A inactivation and overexpression in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J. Bacteriol. 184:3586–3597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harry K. H., Zhou R., Kroos L., Melville S. B. 2009. Sporulation and enterotoxin (CPE) synthesis are controlled by the sporulation-specific sigma factors SigE and SigK in Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 191:2728–2742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hilbert D. W., Piggot P. J. 2004. Compartmentalization of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis spore formation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:234–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Illing N., Errington J. 1991. Genetic regulation of morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis: roles of sigma E and sigma F in prespore engulfment. J. Bacteriol. 173:3159–3169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones D. T., et al. 1982. Solvent production and morphological changes in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:1434–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones D. T., Woods D. R. 1986. Acetone-butanol fermentation revisited. Microbiol. Rev. 50:484–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones S. W., et al. 2008. The transcriptional program underlying the physiology of clostridial sporulation. Genome Biol. 9:R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones S. W., Tracy B. P., Gaida S. M., Papoutsakis E. T. 2011. Inactivation of sigmaF in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824 blocks sporulation prior to asymmetric division and abolishes sigmaE and sigmaG protein expression but does not block solvent formation. J. Bacteriol. 193:2429–2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khvorova A., Zhang L., Higgins M. L., Piggot P. J. 1998. The spoIIE locus is involved in the Spo0A-dependent switch in the location of FtsZ rings in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1256–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. King N., Dreesen O., Stragier P., Pogliano K., Losick R. 1999. Septation, dephosphorylation, and the activation of sigmaF during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 13:1156–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kingsford C. L., Ayanbule K., Salzberg S. L. 2007. Rapid, accurate, computational discovery of rho-independent transcription terminators illuminates their relationship to DNA uptake. Genome Biol. 8:R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee S. Y., et al. 2008. Fermentative butanol production by clostridia. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 101:209–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levin P. A., Losick R., Stragier P., Arigoni F. 1997. Localization of the sporulation protein SpoIIE in Bacillus subtilis is dependent upon the cell division protein FtsZ. Mol. Microbiol. 25:839–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Long S., Jones D. T., Woods D. R. 1983. Sporulation of Clostridium acetobutylicum P262 in a defined medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45:1389–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lucet I., Feucht A., Yudkin M. D., Errington J. 2000. Direct interaction between the cell division protein FtsZ and the cell differentiation protein SpoIIE. EMBO J. 19:1467–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mermelstein L. D., Papoutsakis E. T. 1993. In vivo methylation in Escherichia coli by the Bacillus subtilis phage phi3TI methyltransferase to protect plasmids from restriction upon transformation of Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1077–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mermelstein L. D., Welker N. E., Bennett G. N., Papoutsakis E. T. 1992. Expression of cloned homologous fermentative genes in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Biotechnology (NY) 10:190–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nölling J., et al. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:4823–4838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oultram J. D., et al. 1988. Introduction of genes for leucine biosynthesis from Clostridium pasteurianum into C. acetobutylicum by cointegrate conjugal transfer. Mol. Gen. Genet. 214:177–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Papoutsakis E. T. 2008. Engineering solventogenic clostridia. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19:420–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paredes C. J., Alsaker K. V., Papoutsakis E. T. 2005. A comparative genomic view of clostridial sporulation and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:969–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paredes C. J., Rigoutsos I., Papoutsakis E. T. 2004. Transcriptional organization of the Clostridium acetobutylicum genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1973–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piggot P. J., Curtis C. A., de Lencastre H. 1984. Use of integrational plasmid vectors to demonstrate the polycistronic nature of a transcriptional unit (spoIIA) required for sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:2123–2136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmidt R., et al. 1990. Control of developmental transcription factor sigma F by sporulation regulatory proteins SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:9221–9225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scotcher M. C., Bennett G. N. 2005. SpoIIE regulates sporulation but does not directly affect solventogenesis in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J. Bacteriol. 187:1930–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sillers R., Chow A., Tracy B., Papoutsakis E. T. 2008. Metabolic engineering of the non-sporulating, non-solventogenic Clostridium acetobutylicum strain M5 to produce butanol without acetone demonstrate the robustness of the acid-formation pathways and the importance of the electron balance. Metab. Eng. 10:321–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tomas C. A., et al. 2003. DNA array-based transcriptional analysis of asporogenous, nonsolventogenic Clostridium acetobutylicum strains SKO1 and M5. J. Bacteriol. 185:4539–4547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tomas C. A., Welker N. E., Papoutsakis E. T. 2003. Overexpression of groESL in Clostridium acetobutylicum results in increased solvent production and tolerance, prolonged metabolism, and changes in the cell's transcriptional program. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4951–4965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tracy B. P., Gaida S. M., Papoutsakis E. T. 2008. Development and application of flow-cytometric techniques for analyzing and sorting endospore-forming clostridia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7497–7506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tracy B. P., Jones S. W., Papoutsakis E. T. 2011. Inactivation of sigmaE and sigmaG in Clostridium acetobutylicum illuminates their roles in clostridial-cell-form biogenesis, granulose synthesis, solventogenesis, and spore morphogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 193:1414–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tummala S. B., Welker N. E., Papoutsakis E. T. 1999. Development and characterization of a gene expression reporter system for Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3793–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu J. J., Howard M. G., Piggot P. J. 1989. Regulation of transcription of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIA locus. J. Bacteriol. 171:692–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu J. J., Piggot P. J., Tatti K. M., Moran C. P., Jr 1991. Transcription of the Bacillus subtilis spoIIA locus. Gene 101:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.