Abstract

Biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance is influenced by multiple factors. We demonstrated that Pseudomonas aeruginosa tssC1, a gene implicated in type VI secretion (T6S), is important for resistance of biofilms to a subset of antibiotics. We showed that tssC1 expression is induced in biofilms and confirmed that tssC1 is required for T6S.

TEXT

Bacteria growing in biofilms are more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts. Some mechanisms that contribute to the overall antibiotic resistance in a biofilm are mediated by the extracellular matrix, quorum sensing signaling, and stationary-phase stress resistance (10, 15). We have taken a genetic approach to identify genes that are important for biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance by screening for mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with decreased resistance to antibiotics during biofilm, but not planktonic, growth (16). Initial characterization of two genetic loci, ndvB and PA1875 to PA1877, has led to the identification of novel antibiotic resistance mechanisms (16, 26). Here, we investigate another gene identified in the screen, PA14_01020, which is associated with a newly described type VI protein secretion (T6S) system in P. aeruginosa (18).

T6S systems have been studied in several pathogenic organisms, including Vibrio cholerae, Francisella tularensis, Escherichia coli, and P. aeruginosa (3, 20). They have been implicated in several diverse processes, including biofilm formation, toxin delivery, virulence, and fitness in chronic infection (3, 9, 14, 22). The P. aeruginosa genome contains three T6S loci, designated HSI-I, HSI-II and HSI-III (18). In the standard laboratory strain, PAO1, the HSI-I locus encompasses PA0071 to PA0091 and includes PA0084, the ortholog of PA14_01020 (13, 18). This gene is highly conserved among T6S gene clusters and has been designated tssC1 (13, 25). Genes in the HSI-I cluster are negatively regulated by RetS, which also controls expression of several chronic virulence factors (12). Recent work has shown that HSI-I is involved in the secretion of a toxin to bacteria (13). Although tssC1 has not been studied in P. aeruginosa, homologs of tssC1 are necessary for T6S (2, 7, 27). In V. cholerae, the TssB1 and TssC1 homologs (VipA and VipB) form a complex similar to a bacteriophage tail sheath (5). Since we identified tssC1 in a screen designed to identify genes important for biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance, we wanted to confirm that tssC1 was involved in both biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance and T6S.

tssC1 is expressed in biofilms and important for biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance.

The original tssC1 mutant isolated from the screen was a PA14 Tn5 mutant (16). In order to avoid any possible polar effects, we constructed a P. aeruginosa PA14 mutant with an unmarked deletion of tssC1 by allelic exchange (8) (using pEX18Gm), as described previously (16), with the primers listed in Table 1. Loss of tssC1 had no effect on the growth rate of this mutant (data not shown). Since T6S has been implicated in biofilm formation (1), we assessed the ability of the ΔtssC1 mutant to form biofilms at the air-liquid interface of a six-well microtiter plate (Fig. 1) (17). Mutation of tssC1 had no effect on biofilm formation compared to that of the wild-type strain.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence | Use |

|---|---|---|

| tssC1 F1 | TGTAGAATTCCGCTGCAACTGGTCTG | Deletion of tssC1 |

| tssC1 R1 | TTAATCTAGAGGCTGGCGAACTCACTGGT | Deletion of tssC1 |

| tssC1 F2 | TTACTCTAGACAACATCAACCGCTCCTTCA | Deletion of tssC1 |

| tssC1 R2 | GTGTAAGCTTGCACGTTCTGGCGGATGTTC | Deletion of tssC1 |

| tssC1 F3 | AAGGTCGATTCGCTGAACAA | Confirmation of ΔtssC1 |

| tssC1 R3 | ACGATGCACTTCAGGTAATG | Confirmation of ΔtssC1 |

| tssC1 F4 | CTCCAACGACGCGATCAAGT | qPCR |

| tssC1 R4 | TCGGTGTTGTTGACCAGGTA | qPCR |

| retS F1 | GTCAGAATTCGAAGGATGGCCAGGTGGTCA | Deletion of retS |

| retS R1 | CAACTCTAGAGGATCACCAGCAGGTAGA | Deletion of retS |

| retS F2 | CACCTCTAGAAACCTCAACCACGACATCCT | Deletion of retS |

| retS R2 | GGCCAAGCTTTAGAGCACCAGCATCTTCAG | Deletion of retS |

| retS F3 | ATGCTCCTGCTGCTGATGTA | Confirmation of ΔretS |

| retS R3 | TTGGCCAGGATGCGCTTGAT | Confirmation of ΔretS |

| hcp1 F1 | TTAAGAGCTCCGAGACCGACGAGCAACTGA | Deletion of hcp1 |

| hcp1 R1 | TTGGTCTAGAGGCGTGAGTCTTGTCCTTGG | Deletion of hcp1 |

| hcp1 F2 | TTGGTCTAGAGGCTGGAACATCCGCCAGAAC | Deletion of hcp1 |

| hcp1 R2 | TTGGAAGCTTGAACAGCGAAGTGGTGTTGA | Deletion of hcp1 |

| hcp1 F3 | TGCAGGACTGGATCCTCAAC | Confirmation of Δhcp1 |

| hcp1 R3 | CAGCAGCTGGAACAGGAAGA | Confirmation of Δhcp1 |

| tssABC F1 | CAAAGCTTGTGCCCGAGGGATTTCGGTTC | Complementation of tssC1 |

| tssABC R1 | CAGAGCTCCAGGCGCTGTCGTTGAATGCC | Complementation of tssC1 |

Fig. 1.

Deletion of tssC1 does not affect biofilm formation. The results of an air-liquid interface assay of biofilm formation of the PA14 wild type and ΔtssC1 and pilB transposon (negative control for biofilm formation) mutants are shown (19). Images (magnification, ×400) of the biofilms were taken after 7 h of growth in M63 medium supplemented with glucose (0.2%), Casamino Acids (0.5%), and MgSO4 (1 mM).

To further explore the phenotype of the ΔtssC1 mutant, we compared the antibiotic resistance phenotype of the ΔtssC1 mutant strain with that of the PA14 wild-type strain. We determined the minimal bactericidal concentration for planktonic cells (MBC-P) and the minimal bactericidal concentration for biofilm cells (MBC-B) for tobramycin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin (antibiotics used to treat P. aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis patients [11, 21]), using the 96-well microtiter dish system (Table 2) (16). We found that deletion of tssC1 resulted in a 2- to 4-fold reduction in resistance in the MBC-B assay to all three antibiotics. In the MBC-P assay, deletion of tssC1 had a minor effect on planktonic resistance; however, results from an MIC assay (a more sensitive assay that measures planktonic antibiotic resistance) (Table 3) revealed that there was no defect in planktonic antibiotic resistance in the ΔtssC1 strain. Together, these results confirmed the importance of tssC1 in biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance. Hcp is an important component of T6S (3, 20). Deletion of hcp1 (HSI-I version of hcp) resulted in a strain that also had a slight defect in biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance (Table 2), suggesting that the HSI-1 T6S system is involved in biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance.

Table 2.

MBCs for the P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type strain and ΔtssC1 and Δhcp1 mutantsa

| Strain | Tobramycin |

Gentamicin |

Ciprofloxacin |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBC-P | MBC-B | MBC-P | MBC-B | MBC-P | MBC-B | |

| PA14 | 16 | 100 | 32 | 800 | 2 | 20–40 |

| PA14 ΔtssC1 | 8–16 | 25 | 32 | 400 | 1 | 10 |

| PA14 Δhcp1 | 8–16 | 50 | 32 | 200 | 2 | 10–20 |

MBCs (in micrograms per milliliter) represent the modes of at least six replicates.

Table 3.

MICs for the P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type strain and ΔtssC1 and Δhcp1 mutants

| Strain | MICa (μg/ml) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobramycin |

Gentamicin |

Ciprofloxacin |

||||

| M63 | LB | M63 | LB | M63 | LB | |

| PA14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| PA14 ΔtssC1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| PA14 Δhcp1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

MICs were determined for strains grown in M63 or LB medium.

The intact PA14 tssC1 gene was cloned into a broad-host-range vector, pJB866, to create pJB866-tssC1. This vector carries the Pm promoter, and expression from this promoter is induced by m-toluic acid (4, 26). Compared with PA14 wild-type planktonic cells carrying the vector alone, the cells that carried pJB866-tssC1 (preinduced with m-toluic acid) showed 2- to 4-fold-higher MIC values for tobramycin and gentamicin, but not ciprofloxacin, suggesting that overexpression of tssC1 in planktonic cells increases antibiotic resistance.

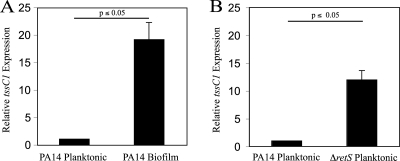

In order to explain the specificity of tssC1 in biofilm but not planktonic resistance, we measured the gene expression of tssC1 in cells grown as planktonic cultures or biofilms by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Table 1 and Fig. 2A). Planktonic cultures were grown in M63 medium (supplemented with 0.4% arginine and 1 mM MgSO4 to an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.6), while biofilms were grown as colonies on M63 agar plates (6). We observed that the tssC1 gene was 18-fold more highly expressed in biofilm cells than in planktonic cells. RetS is a negative regulator of T6S gene expression (12). To confirm that RetS controls expression of tssC1 in PA14 planktonic cells, we constructed a retS deletion strain using PA14 and measured tssC1 expression in the mutant strain by qPCR. As expected, tssC1 was highly expressed in the strain that lacked RetS (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

tssC1 is differentially expressed in PA14 wild-type and ΔretS planktonic and biofilm cultures. Expression of tssC1 in wild-type planktonic and biofilm cells (A) or wild-type and ΔretS planktonic cells (B) was measured by real-time PCR (qPCR) using primers specific for tssC1 (Table 1). Expression of tssC1 in planktonic cells was set at 1. Expression of the housekeeping gene, rpoD, was used as an internal control. Experiments were performed in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

tssC1 is involved in type VI secretion.

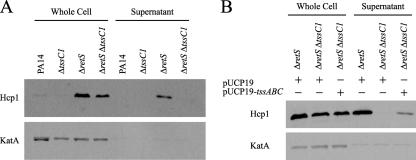

T6S systems are characterized by secretion of Hcp into culture supernatants, which can be used as an indicator of functional T6S (20). In P. aeruginosa, there is no secretion of Hcp1 in planktonically grown wild-type strains but Hcp1 is present in the supernatant of ΔretS mutants (18). It has been demonstrated that tssC1 homologs are required for Hcp1 secretion, but this has not been confirmed in P. aeruginosa. In order to determine if tssC1 is involved in T6S, we tested whether tssC1 inactivation affected Hcp1 secretion. We reasoned that if tssC1 were involved in T6S, then Hcp1 would not be secreted from a ΔretS ΔtssC1 double mutant. We constructed this double mutant strain in a PA14 background and assayed the supernatants from wild-type, ΔtssC1, ΔretS, and ΔretS ΔtssC1 cultures by Western blotting with an antibody to Hcp1 as previously described by Mougous et al. (18) (Fig. 3A). Supernatants were isolated by centrifugation of planktonic cultures grown to late exponential phase in LB medium. As expected, Hcp1 was not secreted by the wild-type PA14 or the ΔtssC1 strains but was secreted by the ΔretS strain. However, Hcp1 was not secreted by the ΔretS ΔtssC1 double mutant, suggesting that tssC1 is required for T6S. The presence of Hcp1 in cell-associated fractions of the ΔretS ΔtssC1 double mutant (Fig. 3A) indicated that the tssC1 mutation abolished secretion but not expression of Hcp1. The ΔretS ΔtssC1 mutant produced slightly less Hcp1 than the ΔretS mutant. Complementation of tssC1 in a ΔretS ΔtssC1 mutant restored Hcp1 secretion (Fig. 3B, pUCP19-tssABC). The vector was constructed by cloning a DNA fragment containing the promoter and open reading frame sequences of tssC1 (as well as the upstream operon genes tssA1 and tssB1) into the medium-copy-number plasmid pUCP19 (24).

Fig. 3.

TssC1 is required for secretion of Hcp1 into culture supernatants. Whole-cell lysates and supernatant fractions were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and assayed for Hcp1 and KatA expression by Western blotting. Levels of the cell-associated protein KatA served as a loading control for the whole-cell fractions and a lysis control for the secreted fractions. (A) Planktonic cultures of the PA14 wild-type strain and ΔtssC1, ΔretS, andΔretS ΔtssC1 mutants were grown in LB medium to late exponential phase prior to analysis. (B) Hcp1 secretion was partially restored in the ΔretS ΔtssC1 strain carrying the complementation vector pUCP19-tssABC.

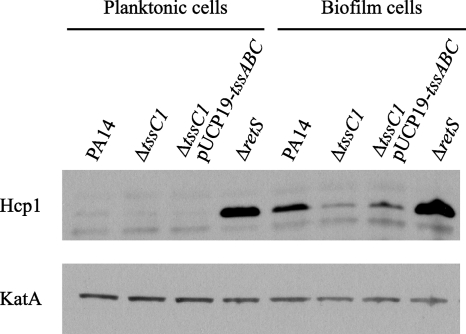

The secretion assay described above was performed using planktonic cultures in which Hcp1 expression is strongly repressed by RetS (18). Our antibiotic sensitivity and gene expression data suggested that tssC1 plays a role in antibiotic resistance of wild-type biofilms. To test whether growth in biofilms leads to increased Hcp1 protein expression, we compared cell-associated Hcp1 levels from planktonic and biofilm cultures of the PA14 parent and ΔtssC1 and ΔretS mutant strains (Fig. 4). Planktonic cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.3 in M63 medium supplemented with 0.4% arginine and 1 mM MgSO4. Static biofilms were grown in the same medium for 48 h in six-well microtiter plates, washed with 0.9% NaCl, and scraped from the sides of the wells. For each strain, Hcp1 levels were significantly higher in biofilm cells than in planktonic cells, although expression was again slightly reduced in the tssC1 mutant. This result, combined with the tssC1 expression data (Fig. 2), suggests that genes encoding components of the T6S system are induced during biofilm growth.

Fig. 4.

Hcp1 levels are greater in PA14 biofilm cells than in planktonic cells. Whole-cell lysates of strains grown as biofilms or planktonic cultures were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and assayed for Hcp1 and KatA expression by Western blotting. KatA expression served as a loading control. Cell suspensions were centrifuged, and cell pellets were suspended in Tris-buffered saline and sonicated prior to SDS-PAGE analysis.

The P. aeruginosa HSI-I T6S system has been implicated in fitness during chronic infections and toxin delivery to bacteria (13). We have shown that an essential component of this secretion system, tssC1, promotes antibiotic resistance in biofilms. To our knowledge, this is the first evidence linking a component of a T6S system to antibiotic resistance. Although the resistance mechanism is unclear, it likely involves an uncharacterized effector of this secretion system. Evidence in P. aeruginosa and other bacteria suggest a role for T6S in mediating bacterial cell-cell interactions (13, 23). Since bacteria in biofilms are in close contact, secretion of an effector between bacteria in biofilms might lead to an antibiotic-resistant state. Investigation of this mechanism could reveal insights into both the function of T6S in P. aeruginosa and the mechanisms responsible for the enhanced resistance of biofilms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

We gratefully acknowledge Joseph Mougous for the gift of Hcp1 antibody. We thank Olle de Bruin and Xian-Zhi Li for critical review of the manuscript and Jenilee Gobin and James Lawless for technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aschtgen M.-S., Gavioli M., Desson A., Lloubes R., Cascales E. 2010. The SciZ protein anchors the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli type VI secretion system to the cell wall. Mol. Microbiol. 75:886–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aubert D., MacDonald D. K., Valvano M. A. 2010. BcsKC is an essential protein for the type VI secretion system activity in Burkholderia cenocepacia that forms an outer membrane complex with BcsLB. J. Biol. Chem. 285:35988–35998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bingle L. E. H., Bailey C. M., Pallen M. J. 2008. Type VI secretion: a beginner's guide. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blatny J. M., Brautaset T., Winther-Larsen H. C., Karunakaran P., Valla S. 1997. Improved broad-host-range RK2 vectors useful for high and low regulated gene expression levels in gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid 38:35–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bönemann G., Pietrosiuk A., Diemand H. Z., Mogk A. 2009. Remodelling of VipA/VipB tubules by ClpV-mediated threading is crucial for type VI protein secretion. EMBO J. 28:315–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Caiazza N. C., Merritt J. H., Brothers K. M., O'Toole A. G. 2007. Inverse regulation of biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:3603–3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Bruin O. M., Ludu J. S., Nano F. E. 2007. The Francisella pathogenicity island protein IglA localizes to the bacterial cytoplasm and is needed for intracellular growth. BMC Microbiol. 7:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donnenberg M. S., Kaper J. B. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Filloux A., Hachani A., Bleves S. 2008. The bacterial type VI secretion machine: yet another player for protein transport across membranes. Microbiology 154:1570–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fux C. A., Costerton J. W., Stewart P. S., Stoodley P. 2005. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 13:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gibson R. L., Burns J. L., Ramsey B. W. 2003. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 168:918–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodman A. L., et al. 2004. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev. Cell 7:5–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hood R. D., et al. 2010. A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 7:25–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jani A. J., Cotter P. A. 2010. Type VI secretion: not just for pathogenesis anymore. Cell Host Microbe 8:2–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mah T. F., O'Toole G. A. 2001. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9:34–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mah T. F., et al. 2003. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426:306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merritt J. H., Kadouri D. E., O'Toole G. A. 2005. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 00:1B.1.1—1B.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mougous J. D., et al. 2006. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science 312:1526–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Toole G. A., Kolter R. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pukatzki S., McAuley S. B., Miyata S. T. 2009. The type VI secretion system: translocation of effectors and effector-domains. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ratjen F., Brockhaus F., Angyalosi G. 2009. Aminoglycoside therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: a review. J. Cyst. Fibros. 8:361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwarz S., Hood R. D., Mougous J. D. 2010. What is type VI secretion doing in all those bugs? Trends Microbiol. 18:531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwarz S., et al. 2010. Burkholderia type VI secretion systems have distinct roles in eukaryotic and bacterial cell interactions. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schweizer H. P. 1991. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene 103:109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shalom G., Shaw J. G., Thomas M. S. 2007. In vivo expression technology identifies a type VI secretion system locus in Burkholderia pseudomallei that is induced upon invasion of macrophages. Microbiology 153:2689–2699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang L., Mah T. F. 2008. The involvement of a novel efflux system in biofilm-specific resistance to antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 190:4447–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng J., Leung K. Y. 2007. Dissection of a type VI secretion system in Edwardsiella tarda. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1192–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]