1. Introduction

The relationship between victimization and offending has been well established in the literature; however, it is not a direct pathway. In order to develop effective prevention and intervention strategies targeting youth violence, a clearer understanding of the underlying factors that contribute to and perpetuate youth violence needs to be determined. In addition to examining long term consequences of youth violence, it is necessary to dissect how we conceptualize victimization and subsequent offending in order to identify a more salient road map towards prevention efforts.

The purpose of this study was to gain new insight into the relationship between victimization and offending among youth by exploring psychological distress as a potential mediating factor. Psychological distress is a term often used in the literature to describe the presence of a number of symptoms including depression, anxiety, anger, dissociation and symptoms of post traumatic stress (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1995; Duncan, 1999; Elkit, 2002; Fitspatrick & Boldizar, 1993; Kopsov, Ruchin & Eiseman, 2003; Rosenthal, Wilson & Futch, 2009). More specifically, this study examined whether different types of victimization are more likely to predict psychological distress and whether psychological distress contributes to offending among study participants over time. In an attempt to isolate the relationship between victimization, psychological distress and offending, the study controlled for a number of individual, family, peer and neighborhood level risk factors commonly linked to both victimization and offending including; (1) age (Lauritsen, 2003), (2) race (Flowers, Lanclos & Kelly, 2002), (3) family structure (Lauritsen, 2003; Sampson & Groves, 1989), (4) parental monitoring and support (Dishion & Loeber, 1985; Barnes and Farrell, 1992), and (5) neighborhood crime rates and perceptions of neighborhood safety (Sampson, Morenoff & Gannon-Rowley, 2002).

1.1. The victimization of youth

Over the past few decades, the influence of victimization research has been copious. It has also primarily focused on connecting childhood victimization such as child abuse and maltreatment to maladaptive behavioral outcomes (Widom, 1989). Early studies failed to demonstrate a causal link because of numerous methodological limitations such as the use of cross sectional retrospective designs, small samples, no comparison groups and failure to control for confounding variables (Widom, 1989b). According to Maschi (2006), research after 1988 provides stronger evidence of a causal relationship by using prospective longitudinal designs, comparison groups and control variables yet they continue to be confounded by other methodological concerns such as the failure to control for adverse experiences including victimization, witnessing violence or experiencing stressful life events particularly after the age of 12. Only recently have researchers begun to explore the victimization of youth indicating that being victimized in adolescence increases the likelihood of future criminal behavior (Chang, Chen, & Brownson, 2003; Shaffer & Ruback, 2002).

It is difficult to capture the true extent to which youth are victimized, yet we know it is happening and research suggests it has far reaching consequences well into the future. As might be expected, the number of youth victimized each year is gravely underestimated. Since youth victimizations are usually reported by family members and other officials rather than the youths themselves (Finkelhor, Cross & Cantor, 2005), official statistics do not accurately reflect the magnitude of this social issue. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey, close to 30% of violent crimes against youth ages 12–17 are ever reported to the police (Finkelhor, et al., 2005). This lack of information presents challenges in determining who is at greatest risk for victimization and why (Snyder & Sickmund, 2006).

1.2 Direct and Vicarious Exposure to Violence

In order to take a comprehensive look at how violence impacts youth and how they subsequently respond to violence, we need to consider both direct and indirect victimization. Youth can be indirectly affected by witnessing violent events or because such events have occurred to members of their immediate family, extended family or acquaintances (Lorion & Saltzman, 1993). Lorion et al., (1993) contend indirect victims should include those who have experienced the threat of violence because of its seeming frequency, ubiquity, and unpredictability.

1.3 The Link between Victimization and Offending

There is a well established body of literature supporting a relationship between past victimization and further perpetration of violence among youth (Baren, 2003; Coleman & Jensen, 2000; Loeber, Kalb & Huizinga, 2001; Welte et al., 2001). Studies that examined underlying risk factors for violent behavior among adolescents have demonstrated a consistent relationship between victimization and the perpetration of violence. For example, Loeber et al. (2001) examined data from the Denver Youth Study and the Pittsburg Youth Study and found that 49% of males who were serious, violent offenders were violently victimized in the past compared to 12% of non-delinquent youth. The authors contend that violent victimization, in turn, is thought to increase the risk of delinquent acts. Loeber et al. (2001) contends that youth victimization and offending are often intertwined and mutually stimulate each other.

A growing body of literature around vicarious victimization through exposure or by witnessing violence continues to emerge (Abran, Telpin, Charles, Longworthy, McClelland & Duncan, 2004; Brookmeyer, Henrich & Schwab-Stone, 2005; Nofziger, 2005). A high degree of exposure to family and community violence has been found among adjudicated youth (Maschi, 2006). Additionally, witnessing violence was the most common trauma among a sample of juvenile detainees in a large Chicago detention center (Abrams et al., 2004). Almost 60% reported being exposed to six or more traumatic events. Shaeffer et al., (2002) further explored the relationship between violent victimization and violent offending across a two year period and found that juveniles who were victims of violence in year one were significantly more likely than non-victims to commits a violent offense in the second year.

1.4 Chronic Victimization

More recently, Maschi (2006) explored how differential versus cumulative effects of trauma related to victimization influence delinquency in adolescent boys to better understand whether the magnitude of specific or differential risk factors or the accumulation of risk factors increased the risk of delinquent behavior. To do this Maschi (2006) included key variables related to direct victimization, witnessing family and community violence and experiencing stressful life events in order to create a comprehensive measure of trauma. In addition, he controlled for common correlates of delinquent behavior including, age, race, ethnicity, social class, family structure, geographic location, delinquent peer exposure negative affect and social support (Maschi, 2006). Analysis suggested that cumulative effects of exposure to stressful life events significantly increased the odds of non-violent offending (specifically property crimes) and exposure to both violence and stressful life events predicted violent delinquency. Maschi (2006) reported that lower family income, fragmented family structure and minority status significantly influence violent offending under the cumulative model.

Some children experience violence as a chronic feature of life (Gutterman & Cameron, 1997). A growing body of literature strongly underscores the destructive impact of trauma brought on by multiple exposures to violence within families and communities (Attar, Guerrra, & Tolan, 1994). Garbarino and Kostelny (1997) suggest that youth exposed to chronic violence adapt to it rather than be overwhelmed by it. They contend that children and youth living in these high crime areas become psychosocially desensitized from repeated exposure to violence which spares them the immediate emotional distress but unfortunately increases the propensity for violence. Adolescents attempting to cope with persistent fear of harm may attempt to alleviate anxiety by identifying with and joining aggressive individuals in the neighborhood (Schwab-Stone et al, 1995). Likewise, repeated adolescent victimization was found to be associated with delinquency recidivism (Chang, Chen & Brownson, 2003).

1.5 The Link Between Victimization and Psychological Distress

Violent victimization and exposure to violence (i.e., in the home and neighborhood) are associated with a variety of short-and long-term mental health issues in children and adolescents including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), aggression and confrontational coping styles often associated with psychological distress (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1995; Duncan, 1999; Elkit, 2002; Fitspatrick & Boldizar, 1993; Kopsov, Ruchin & Eiseman, 2003). For the most part, studies of community violence view it as a form of stress that psychologically overwhelms children and gives rise to depressive symptoms, anxiety and/or PTSD symptomatology (Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Felman & Stueve, 2002). What is less clear is whether the type of victimization, or the resulting psychological distress better predicts subsequent offending behavior among children and youth.

Wilson and Rosenthal (2003) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the relationship between exposure to community violence and psychological distress among adolescents. They sought to move beyond determining a linear relationship between exposure to community violence and psychological distress to assessing the “size” of that relationship. They reviewed relevant empirical studies that met specific criteria spanning 20 years and found support for a positive correlation between community violence exposure and psychological distress, although with a low to medium effect size (r=.25). Wilson and Rosenthal (2003) found a number of limitations across studies (i.e. Gutterman & Cameron, 1997; Mazza & Overstreet, 2000). It appeared as if studies consistently identified a relationship between exposure to violence and psychological distress, yet they did not differentiate between the types of violence exposure (i.e. child abuse, domestic violence, community violence) (Wilson et al., 2003). The current study attempts to fill that gap by distinguishing between types of direct and indirect victimization among youth and psychological distress.

Additionally, Johnson, Kotch, Catellier, Winsor, & Hunter et al. (2002) examined mental health outcomes among children who experienced physical abuse and/or witnessed violence in their neighborhood. Their study is one of few to use longitudinal data and control variables to examine this issue. The sample (n=167) was comprised of 60% female and 64% non-white youth (Johnson et al., 2002). Physical abuse was reported by one third of the participants and nearly half of the sample indicated that they had been a witness to either family or neighborhood violence. They reported on the levels of violence witnessed by the child through child and parent reports. Like most studies measuring exposure, they limited the measure to events the child saw or heard. Additionally, they aggregated family and neighborhood exposure to violence into one measure making it impossible to determine which had a greater effect. Among participants, victimization was significantly associated with increased depression and aggression and exposure to violence was found to be significantly related to aggression, depression, anger, and anxiety (Johnson et al., 2002). The current study expands the traditional definition of exposure to include events that the youth is aware of in their neighborhood, home and among peers (not necessarily witness to). Additionally, it delineates between vicarious victimization through exposure to violence through the neighborhood, family and peers separately.

1.6 Study hypotheses

This study aims to test the following hypotheses; (1) direct and vicarious victimization will significantly predict offending at wave one and two, (2) there will be a significant relationship between direct and vicarious victimization and psychological distress, (3) psychological distress will significantly predict offending at wave one and two, (4) wave 1 offending will significantly predict offending at wave 2, and (5) psychological distress will mediate the relationship between victimization and offending at both waves.

2. Methods

2.1 Data

The current study was a secondary data analysis utilizing data from wave one and wave two of the Buffalo Longitudinal Study of Young Men (BLSYM), from the city of Buffalo, New York. The BLSYM is a five year panel study that began in 1992 and was designed to examine multiple causes of adolescent substance abuse and delinquency (Zhang, Welte & Wieczorek, 2001). Wave 1 and wave 2 were utilized in an effort to develop a more sophisticated model to examine the relationship between predictor and outcome variables over time. Wave one data was collected from 1992–1993 and wave two data from 1994–1995. The BLSYM was supported by a five year grant (# RO1 AA08157) through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Zhang, et al., 2001).

2.2 Study Participants

The BLSYM study included a general population-based sample of 625 males between the ages of 16 and 19, and 625 family respondents (i.e., the main care giver, usually the male adolescent’s mother). In order to be eligible for the study, primary respondents had to have a parent or caregiver participate in wave one of the study. All measures for the study were based on adolescent and parent/caregiver self-reports (Zhang et al., 2001). Recruitment was a detailed, multi-step process as reported in Welte and Wieczorek (1998). Informed consent was obtained from both respondents. Separate, face-to-face, structured interviews were conducted by trained interviewers at the Research Institute on Addictions (Welte, Barnes, Hoffman, Wieczorek, & Zhang, 2005).

In the initial wave 74% (n=625) of the households identified contained an eligible male who agreed to participate in the structured interview phase of the study (Welte et al., 2005). The racial composition of the original sample consisted of 49% white, 45% African American and 6% from other racial/ethnic backgrounds (Zhang, Wieczorek, & Welte, 2002). The BLSYM over-sampled in high crime areas in Buffalo, yet a broad spectrum of income groups are represented (Zhang et al., 1999).

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Independent variables

Items in the BLSYM measuring victimization were originally taken from the National Youth Survey questionnaire (Elliot, Huizinga & Ageton, 1985). They measured the extent to which the young male was victimized by crime. For purposes of this study, type of victimization was delineated into two distinct categories: (1) direct and (2) vicarious victimization. Additional subcategories were made in each category. For direct victimization, distinctions were made between (a) personal and, (b) property victimization. For vicarious victimization measures, distinctions were made between exposure to violence in (1) the neighborhood (2) family and, (3) with close friend/peers.

2.3.1.1 Direct victimization

Nine items were used to create two linear composites as indicators of crime victimization for both personal (3 items) and property (6 items) victimization. Log transformations were used to normalize the distribution of each (Zhang et al., 2001, p.137). For each direct victimization subcategory, the variables were created by summing frequencies across items representing the true total for each. The higher the total, the greater the direct victimization.

2.3.1.1.1 Personal victimization

The frequency of personal victimization was measured by asking primary respondents how many times (representing the true total number of times) they had the following things happen to them in the past twelve months: (1) been confronted and had something taken directly from you or an attempt made to do so by force or threatening to hurt you, (2) been sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) been beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beat up or attacked by someone (excluding sexual attack or rape).

2.3.1.1.2 Property victimization

The frequency of property victimization was measured by asking primary respondents how many times (representing the true total number of times) they had the following things happen to them in the past twelve months: (1) something stolen from their households or an attempt to do so, (2) while they weren’t around, had their bicycles stolen or an attempt made to do so, (3) while they weren’t around, had their cars or motorcycles been stolen or attempts made to do so (4) had their things been damaged on purpose, such as cars or bike tires slashed, windows broken or clothes ripped up, (5) had things stolen from places other than their home or any public place such as a restaurants, schools, parks or streets, (6) had their pockets picked, purses, bags or wallets snatched or attempts made to do so.

2.3.1.2 Vicarious victimization

Indices were created for all three vicarious victimization variables (vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the neighborhood, family and peers) by summing across items regarding the primary respondent’s responses to items regarding knowledge of the events that occurred in their neighborhood, happened to their family members or to their peers. For each separate category, a higher number indicates greater vicarious victimization by exposure to violence.

2.3.1.2.1 Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the neighborhood

Primary respondents were asked how often (1=never, 2=once, 3=twice or more) in the past 12 months they had knowledge of someone in the neighborhood (1) being robbed, (2) seriously assaulted, beat-up, shot or stabbed (3) sexually assaulted or (4) threatened with physical harm by someone outside their family.

2.3.1.2.2 Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the family

Primary respondents were asked how many times in the past twelve months (1=never, 2=once, 3=twice or more) has anyone who lived with the primary respondent (excluding the primary respondent) (1) been confronted or had something directly taken from them or an attempt was made to do so, (2) been sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) been beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beaten up or attacked by someone.

2.3.1.2.3 Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peer group

Primary respondents were asked, how many times in the past twelve months (1=never, 2=once, 3=twice or more) has a close friend (1) been confronted or had something directly taken from them or an attempt was made to do so, (2) been sexually attacked or raped or an attempt made to do so, (3) been beaten-up or attacked or threatened with being beaten up or attacked by someone.

2.3.2 Dependent Variables

2.3.2.1 Psychological distress

Psychological distress in this study is broadly defined as the presence of psychological symptoms that negatively impact the functioning of the primary respondent. The BLSYM instrument embedded 23 of the original 53 questions from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) to obtain a psychological distress measure. The empirical rationale for doing so is that evidence indicates different psychological symptoms of distress such as anger, anxiety, depression, PTSD and, dissociation appear highly inter-correlated (Compas & Hammen, 1994). The 23 questions were drawn from four specific symptom scales from the BSI: (1) obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), (2) depression, (3) anxiety and, (4) psychoticism. Respondents were asked how often they were distressed by each symptom using a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 0= not at all to 4= always. The psychological distress variable was created by calculating the means of total scores for each symptom scale. The reported reliability coefficients for each symptom dimension were as follows; (1) OCD= .87, (2) depression= .89, (3) anxiety= .86 and, (4) psychoticism= .75 (Boulet & Boss, 1991). Examples of OCD items included; trouble remembering things, feeling blocked in getting things done, having to check and double-check what you do, difficulty making decisions, your mind going blank and trouble concentrating. Depression examined whether respondents ever had thoughts of ending your life, feeling lonely, feeling blue, feeling no interest in things, feeling hopeless about the future, and feelings of worthlessness. Anxiety was measured by asking questions about how much respondents felt nervousness or shakiness inside, suddenly scared for no reason, feeling fearful, feeling tense and keyed up, spells of terror or panic and feeling so restless you couldn’t sit still. Psychoticism was explored by asking respondents how often they felt, that someone else can control their thoughts, lonely even when they are with people, felt they should be punished for their sins, never felt close to another person, and believe the idea that something is wrong with their mind.

2.3.2.2 Offending (Wave 1 & 2)

This question was adopted from the National Youth Survey (Elliot, Huizinga & Ageton, 1985). In general, offending in this study refers to the commission of both non-violent and violent acts by the primary respondent. Total offending represents an aggregate of the total frequency of offending for each primary respondent, regardless of the seriousness of the offense. The measure includes delinquent acts that did not result in charges being filed, an arrest or a conviction as well as more serious offenses whereas an arrest and conviction were made such as aggravated assault (Zhang et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2001; Barnes et al., 1999). Primary respondents were asked how many times in the last 12 months (representing a true count) they committed any of the listed 34 delinquent acts (see Appendix A). The log transformation computed in the original BLSYM was used to normalize the distribution (Zhang et al., 1999). This measure includes delinquent acts that did not result in charges being filed, an arrest or a conviction. Analyzed together, the 34 items have a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 and a reported internal consistency reliability for the constructed measures ranged from .76 for general delinquency to .49 for minor delinquency (Welte et al., 2005).

3. Statistical Analysis

SPSS (PASW Statistic 18) software was used for data screening, descriptive analyses and the log transformation of several variables. Evaluation of distributions led to the natural log transformations (with a constant added to avoid taking the log of zero) of personal, property and vicarious victimization variables (in the family and among peers only) as well as total offending. MPlus software, version 5.2 was used for path analyses to examine the causal interrelationships among study variables.

3.1 Descriptive statistics

Primary respondents ranged in age from 15 to 20 years old (M=17.3, SD=1.14). The ages in the sample were somewhat equally distributed, 16 (28%), 17 (25.4%), 18(24.8%) and 19(20.3%) years old. The sample was primarily White, non-Hispanic (47.3%) and Black, non-Hispanic (47.1%). At the time of the study, 72.3% of primary respondents were currently in enrolled in school.

3.1.1 Family, peer and neighborhood

The mean age of biological mothers and fathers were 42 and 44 years respectively. The racial composition of families were 45% White, 44.5% Black, and 7% Hispanic. Only 23% of primary respondents lived with both biological parents at the time of the study. The highest percentage (32.2%) resided in single parent homes (mother head of households). Only 24% of biological mothers and 17.3% of biological fathers held a college degree. The majority of biological mothers (52%) and biological fathers (67.1%) held a high school diploma. Over half (54%) of the family respondents reported a yearly income less than $20,000. The mean yearly income was between $20,000–$30,000.

Slightly over half (53%) of the primary respondents reported their current friends live in their neighborhood. 56.2% reported having the same friends since childhood.

Approximately half (53.3%) of the primary respondents lived in the same neighborhood most of their lives. Based on perceptions of criminal activity in the neighborhood, 43% (n=273) reported living in lower crime neighborhoods whereas, 56% (n=352) perceived living in moderate to high crime neighborhoods. In addition, 39% rated their perception of person safety in their neighborhood as “good” or “excellent”; whereas the majority felt fairly safe (34%) or not safe at all (27.5%).

3.1.2 Victimization

Almost half (46.8%) of the sample reported being personally victimized at least one or more times and 56% reported being a victim of property crime one or more times. When asked a series of questions related to respondent’s knowledge of victimization occurring against others in their neighborhood, 72.4 % recalled having knowledge of one or more robberies, 63.1 % knew of one or more serious assaults and 24.9% had knowledge of one or more sexual assaults that occurred in their neighborhood. The majority of primary respondents (82.9%) reported no knowledge of violence against family members. Whereas, 40% of respondents reported having knowledge of peers in the neighborhood being beat up or attacked, yet only.1% indicated knowledge of a sexual assault against one of their peers.

3.1.3 Psychological distress

Measures of psychological distress among primary respondents ranged from 0 to 3.83 out of a possible 4.0 (M=.89, SD=.60). A higher score indicated higher levels of psychological distress.

3.1.4 Offending

Overall, primary respondents reported more non-violent than violent offending. The highest percentage (83%) of primary respondents reported perpetrating at least one non-violent offense. 62% reported perpetrating multiple non-violent offenses (over 5) in the past year. Only 18.7% indicated they never committed a non-violent offense as defined by the study. Over half (65.4%) of the primary respondents reported committing at least one violent offense and 33.4% reported committing multiple violent offenses. 34.6 % of respondents indicated they never committed a violent act as defined by the study. Total offending decreased slightly from wave 1 (M=240.18, SD=509.6) to wave 2 (M=166.03, SD (381.83).

3.2 Correlations

Table 1 shows the zero order correlations between the variables used in this study. Of specific interest were relationships between (1) offending and victimization, (2) victimization and psychological distress, and (3) psychological distress and offending. Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the family was not significantly related to offending or psychological distress. Personal and property victimization, as well as vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through peer and the neighborhood was significantly associated with offending at wave 1. Direct personal victimization as well as vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through peer and neighborhood was significantly associated with offending at Wave 2. Direct personal and property victimization, as well as vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through peers and neighborhood victimization was significantly associated with psychological distress.

Table 1.

Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Offending wave 1 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Offending wave 2 | 0.622*** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Psych distress | 0.142*** | 0.148*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 | Personal vict | 0.410*** | 0.280*** | 0.147*** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Property vict | 0.180*** | 0.085 | 0.124** | 0.181*** | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 6 | Vicarious: family | 0.029 | 0.003 | 0.026 | 0.045 | 0.091** | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Vicarious: peers | 0.373*** | 0.302*** | 0.108** | 0.271*** | 0.145*** | −0.019 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 8 | Vicarious: neigh | 0.388*** | 0.240*** | 0.092** | 0.174*** | 0.115** | 0.095 | 0.092** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Neighborhood crime | 0.401*** | 0.223*** | 0.070 | 0.197*** | 0.160*** | 0.080 | 0.155*** | 0.819*** | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 10 | Perception of safety | 0.211*** | 0.118** | 0.047 | 0.133** | 0.090** | 0.069 | 0.055 | 0.466*** | 0.686*** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 11 | Parent monitoring | −0.319*** | −0.251*** | −0.063 | −0.144*** | −0.074 | −0.021 | −0.028 | −0.220*** | −0.258*** | −0.237*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 12 | Single parent | −0.135** | −0.097 | −0.026 | −0.058 | −0.035 | −0.045 | −0.022 | 0.033 | 0.074 | 0.068 | 0.013 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 13 | Parent/sig. other | 0.058 | 0.075 | −0.009 | −0.004 | 0.018 | 0.085** | 0.032 | 0.071 | 0.067 | 0.082** | −0.021 | −0.363*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 14 | Other living arrange | 0.130** | 0.070 | 0.036 | 0.053 | 0.066 | 0.007 | −0.027 | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.080** | −0.127** | −0.368*** | −0.282*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 15 | SES | −0.052 | −.004 | 0.056 | 0.019 | −0.020 | 0.002 | 0.107** | −0.159*** | −0.208*** | −0.213*** | 0.137*** | −0.167*** | −0.014 | −0.078 | 1.000 | |||

| 16 | Race | 0.024 | 0.014 | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.004 | 0.023 | −0.073 | 0.098** | 0.204*** | 0.240*** | −0.096** | 0.112** | 0.016 | 0.127** | −0.185*** | 1.000 | ||

| 17 | Mom support | −0.132** | −0.122** | −0.115** | −0.066 | −0.059 | −0.006 | 0.024 | −0.099** | −0.121** | −0.128** | 0.458*** | 0.080** | −0.032 | −0.093 | 0.070 | 0.092** | 1.000 | |

| 18 | Dad support | −0.095** | −0.091** | −0.090** | −0.039 | −0.041 | −0.081** | 0.022 | −0.101** | −0.166*** | −0.108** | 0.295*** | −0.047 | −0.084** | 0.020 | 0.111** | 0.065 | 0.319** | 1.000 |

Notes: Personal victa= personal victimization. Vicarious: familyb =Vicarious exposure to violence through the family; same with peers and neighborhood. Variables 12 through 14 describe family structure.

p< .001 level,

p<.05 level

3.3 Path analyses

The analyses considered relationships between variables from a causal standpoint. Wave 1 measures were used to predict wave 2 offending. Likewise, it was assumed that wave 1 offending was a function of factors that preceded the offending to some degree. Psychological distress was assumed to be a result of prior victimization, family, peer and neighborhood characteristics, while victimization was seen as resulting from parent, peer and neighborhood factors.

The Chi-Square, Comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and weighted root mean square residual (WRMR) were used as the fit indices. The procedure used for estimation of the path model was maximum likelihood. Initial path models included paths from the exogenous to the endogenous and outcome variables (See Tables 2–5).

Table 2.

Initial model: Exogenous variables on offending (Wave 2 & Wave 1)

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-tailed P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offending Wave 2 On | ||||

| Offending Wave 1 | 0.571 | 0.036 | 15.884 | <.001*** |

| Psych Distress | 0.054 | 0.032 | 1.695 | 0.090* |

| Neigh Crime | −0.089 | 0.069 | −1.287 | 0.198 |

| Perception Safe | 0.010 | 0.044 | 0.217 | 0.829 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.060 | 0.038 | −1.599 | 0.110* |

| Single Parent | −0.012 | 0.032 | −0.369 | 0.712 |

| SES | 0.018 | 0.033 | 0.551 | 0.582 |

| Race | 0.019 | 0.033 | 0.580 | 0.562 |

| Mom Support | −0.015 | 0.036 | −0.426 | 0.670 |

| Dad Support | −0.021 | 0.034 | −0.614 | 0.539 |

| Personal Vic | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.528 | 0.597 |

| Property Vic | −0.038 | 0.032 | −1.179 | 0.238 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.014 | 0.031 | −0.437 | 0.662 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.084 | 0.034 | 2.450 | 0.014** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.962 | 0.336 |

| Offending Wave 1 On | ||||

| Psych Distress | 0.045 | 0.032 | 1.404 | 0.160 |

| Neigh Crime | 0.268 | 0.068 | 3.919 | <.001*** |

| Perception Safe | −0.103 | 0.044 | −2.313 | 0.021** |

| Parent Monitor | −0.215 | 0.036 | −5.890 | <.001*** |

| Single Parent | −0.133 | 0.032 | −4.195 | <.001*** |

| SES | −0.033 | 0.033 | −1.016 | 0.309 |

| Race | −0.008 | 0.033 | −0.244 | 0.807 |

| Mom Support | 0.026 | 0.036 | 0.722 | 0.471 |

| Dad Support | −0.006 | 0.034 | −0.190 | 0.849 |

| Personal Vic | 0.244 | 0.033 | 7.467 | <.001*** |

| Property Vic | 0.034 | 0.032 | 1.070 | 0.284 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.014 | 0.031 | −0.435 | 0.663 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.240 | 0.033 | 7.319 | <.001*** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.077 | 0.056 | 1.367 | 0.172 |

p<.001,

p<.05,

p<.10

Table 5.

Initial Model: Exogenous Variables Vicarious Victimization Variables

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious: Peer On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.082 | 0.085 | 0.966 | 0.334 |

| Perception Safe | −0.029 | 0.055 | −0.525 | 0.600 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.035 | 0.046 | −0.761 | 0.447 |

| Single Parent | −0.006 | 0.040 | −0.147 | 0.883 |

| SES | 0.126 | 0.040 | 3.121 | 0.002** |

| Race | −0.085 | 0.041 | −2.065 | 0.039** |

| Mom Support | 0.054 | 0.045 | 1.201 | 0.230 |

| Dad Support | 0.027 | 0.042 | 0.650 | 0.515 |

| Vicarious: Family | −0.036 | 0.039 | −0.927 | 0.354 |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.171 | 0.069 | 2.466 | 0.014** |

| Vicarious: Family On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | −0.034 | 0.087 | −0.393 | 0.695 |

| Perception Safe | 0.045 | 0.057 | 0.800 | 0.424 |

| Parent Monitor | 0.018 | 0.047 | 0.384 | 0.701 |

| Single Parent | −0.054 | 0.041 | −1.339 | 0.181 |

| SES | 0.022 | 0.042 | 0.528 | 0.598 |

| Race | 0.025 | 0.042 | 0.580 | 0.562 |

| Mom Support | 0.027 | 0.046 | 0.584 | 0.559 |

| Dad Support | −0.090 | 0.043 | −2.119 | 0.034** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.102 | 0.071 | 1.433 | 0.152 |

| Vicarious: Neigh On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.944 | 0.023 | 40.336 | <.001*** |

| Perception Safe | −0.174 | 0.031 | −5.589 | <.001*** |

| Parent Monitor | −0.027 | 0.026 | −1.009 | 0.313 |

| Single Parent | −0.021 | 0.023 | −0.934 | 0.350 |

| SES | −0.011 | 0.023 | −0.457 | 0.648 |

| Race | −0.056 | 0.024 | −2.372 | 0.018** |

| Mom Support | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.536 | 0.592 |

| Dad Support | −0.004 | 0.024 | −0.168 | 0.867 |

p<.001,

p<.05,

p<.10

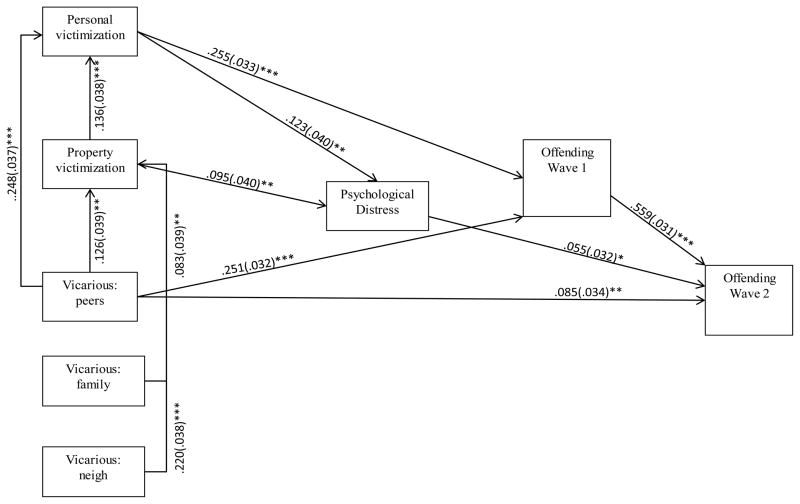

Using results from the initial regressions as our starting point, results were evaluated and all non-significant pathways were removed until a final best fitting model was obtained. The final model was determined by a non-significant Chi-Square, CFI and TLI both over .95, RMSEA below .05, and WRMR below .8. Results for this analysis are shown in Figure 1. The fit for the final revised model was Chi-Square = 52.18, df = 92, n = 625, p = .892; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.01; RMSEA = .000; WRMR = .024.

Figure 1.

Path Diagram for Final Model, ***p<.001, **p<.05, *p<.10

3.3.1 Hypothesis 1: Direct and vicarious victimization measures will significantly predict offending at wave one and two

Table 2 shows the regression results for offending at wave 1 and 2. Personal victimization was positively associated with wave 1 offending but not wave 2. Only vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through peers showed significant positive relationship with wave 1 and 2 offending. Additionally, consideration of vicarious victimization in the model shows that while the relationship between personal victimization and offending becomes non-significant as time passes, peer victimization remains a strong indicator.

3.3.2 Hypothesis 2: There will be a significant relationship between direct and vicarious victimization and psychological distress

There was a significant, positive relationship between both personal and property victimization and psychological distress. Vicarious victimization as defined in this study did not appear to be significant predictors of psychological distress.

3.3.3 Hypothesis 3: psychological distress will significantly predict offending in wave 1 and 2

Psychological distress was not associated with offending at wave 1, yet it appeared to have a marginal association with wave 2 offending.

3.3.4 Hypothesis 4: Wave one offending will significantly predict offending at wave 2

Wave one offending showed a significant relationship with wave 2 offending.

3.3.5 Hypothesis 5: Psychological distress will mediate the relationship between victimization and offending at both waves

There was not support for psychological distress acting as a mediator between victimization and offending. The final model suggests that both personal and property victimization significantly predict offending at wave 1 yet, no relationship exist between psychological distress and offending at wave 1. In addition, neither personal nor property victimization are significant predictors of offending at wave 2. Therefore, psychological distress cannot be a mediator.

4. Discussion

Breaking down direct and indirect victimization into subcategories for analysis was an attempt to fill a gap in the literature. Most of the existing studies aggregate types of victimization and they are rarely tested simultaneously across individual, family and neighborhood level variables. This study was an attempt to explore the relationship between the different types of victimization and offending simultaneously. We wanted to know whether type of victimization made a difference in terms of offending. Specifically, was one type more likely to predict subsequent offending more than others?

Additionally, most studies in the literature define vicarious (indirect) victimization as “witnessing”. We wanted to test whether having knowledge of a violent crime/event made a difference in terms of one’s propensity to offend. Moreover, we wanted to know whether people who experience direct victimization (personal or property) are more apt to offend than those indirectly exposed to violence in neighborhoods, families and against peers? Among direct victimization variables we expected personal victimization to be the strongest predictor of offending due to the direct nature of the experience. Findings supported this, indicating that personal victimization was highly significant in predicting offending at wave 1. Interestingly, it dropped out of the model at wave 2, suggesting that when someone is personally victimized the propensity toward offending is more likely to occur as more immediate generalized retaliation shortly after they’ve been victimized as opposed to a long-term, retaliatory response over a longer time frame.

Among vicarious victimization variables, we expected vicarious victimization by exposure to violence through the Neighborhood, family and peers to be strong predictors of offending based on past research that suggests that youth exposed to chronic violence adapt to it as a means of self preservation and protection which spares them immediate distress but increases the likelihood of violence in the future (Garbarino & Kostelny, 1997; Maschi, 2006). Data did not support the relationship between vicarious victimization by exposure to violence in the neighborhood or in the family and subsequent offending. But, it did support the relationship between vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers and offending at both waves. This reinforces the importance of the peer groups in the lives of youth. Young males exposed to violence among their peer groups may be more likely to commit subsequent crimes by virtue of who they are interacting with. This would be important information for parents and guardians to know as they monitor friends. Additionally, it would be critical for interventions to include elements that (1) assist youth in identifying negative peer relationships and (2) aim to foster a healthy, supportive friendship network.

We anticipated results related to vicarious victimization through the family to be somewhat limited due to the guarded nature of family issues. Sexual assault and violence within family boundaries tends to be somewhat enigmatic and not openly disclosed for several reasons, including the possibility to retaliation or dissolution of the family unit. In addition, the variable created for this study asked respondents about assaults and sexual assaults/rape of family members, which respondents may not have any knowledge of. This may be worth exploring further in future research.

This study supports findings in literature that link victimization to psychological distress in the form of anxiety, depression, and/or PTSD (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1995; Fitspatrick & Boldizar, 1993; Kopsov, Ruchin & Eiseman, 2003; Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Felman & Stueve 2002). As an added element, we wanted to know whether type of victimization impacted youth differently in terms of psychological distress. For example, does having property stolen or being physically/sexually assaulted make a difference in terms of psychological distress? We hypothesized that personal victimization would better predict psychological distress due to the individual nature of the offense. Interestingly, findings indicated a significant relationship between both personal and property victimization and psychological distress. This suggests that individuals may view their property as extension of themselves. Property crime may leave residents feeling just as violated, unsafe and living in anxiety and fear of a reoccurrence as does personal violent victimization. These findings may suggest there is the potential for a property crime to yield a more deleterious outcome based on fear. Boney-McCoy et al. (1995) indicated that a fear of re-victimization can elicit high degrees of anxiety, PTSD, depression and aggressive behavior among individuals. The underlying fear of potential outcomes (getting shot, raped, killed) may be the common thread linking the two to psychological distress.

The current study did not support findings in the literature indicating a strong relationship between vicarious victimization and psychological distress (Gutterman & Cameron, 1997; Johnson, Kotch, Catellier, Winsor, Hunter et al., 2002; Kliewer, Murrelle, Mejia, Torres & Angold, 2001; Kuther, 1999; Mazza & Overstreet, 2000; Wilson et al., 2003). Vicarious victimization, as defined in this study, did not appear to have any predictive importance with respect to psychological distress. We expected all three to predict psychological distress but, to differing degrees. Data did not support this. This may suggest (1) that youth indirectly exposed to violence in the neighborhood, among peers and in their family become psychologically desensitized to it, as suggested by Garbarino et al. (1992), (2) youth may employ external responses to vicarious victimization by altering their behavior in an effort to navigate their unsafe environment. Vicarious victimization presumes by definition that the violence is not specifically directed toward the individual, therefore, it may not signal an internal (psychological) response. In addition, gender may be a factor in how youth react to vicarious victimization. Past research indicates psychological effects of violence exposure are more pronounced in younger females (Kliewer et al., 2001). This may, in part, explain the lack of findings among an all male sample.

The literature suggests incarcerated youth present with high incidents of mental health issues including anxiety, depression, and PTSD. We wanted to test whether psychological distress among our sample of non-incarcerated youth predicted subsequent offending. We expected psychological distress to have a strong association with offending at wave 1 and to be even stronger at wave 2 (based on a cumulative model). Since psychological distress interferes with an individual’s ability to cope and make sound judgments, it seemed likely that it would be a significant predictor. Interestingly, the relationship between psychosocial distress and offending was non-existent at wave 1 and significant yet, marginal at wave 2. This may provide some support that over time psychological distress may have a more cumulative effect and ultimately a larger impact on recidivism. This has implications for practice suggesting that if left untreated, these youth may develop more of a propensity to re-offend.

Since our findings suggest a highly significant relationship between personal victimization and offending at wave 1 but not wave 2, we should be cognizant of the element of time. Psychological distress may be key. If left untreated, or unidentified, psychological distress may move youth toward a greater likelihood to offend overtime.

In light of the fact that the individual relationships between direct victimization and psychological distress and psychological distress and offending (wave 2) were significant, it is possible psychological distress may be acting as a confounding variable which helps to somewhat explain (as opposed to cause) the relationship between victimization and offending (McKinnon et al., 2000). Further exploration of this relationship may be warranted in the future, as well as other potential factors that may be contributing to psychological distress and offending, such as alcohol and other drug abuse, school-related difficulties, and family histories of offending and or psychiatric problems.

4.1 Study limitations

One limitation of this study is the all male sample. Findings cannot be generalized to female youth. In addition, it is not uncommon for males to hide or not disclose sexual assault/rape. Therefore, we may not have a true picture of the magnitude of personal victimization as defined in this study (Hartinger-Saunders, 2008). All measures were based on self-report. Although it is not uncommon for this age group to either inflate responses or to not disclose elements altogether, the consent procedures, research setting for the interview, and specified methods for protecting confidentiality of the participants are all procedures designed to optimize the validity of these measures. Similarly, there is the potential for criticism based on the common issues in research related to retrospective recall but the continuously updated 12-month timeline of major events was used to anchor the time frame for each participant.

4.2 Implications

Findings suggest the importance of highlighting collective responsibility in addressing victimization, psychological distress, and offending behavior among youth. Knowledge that a child or youth has been personally victimized should alert parents, educators, and mental health practitioners to their potential to develop symptoms of psychological distress and for future offending. However, knowledge that a child or youth has experienced vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers, or has a poor perception of neighborhood safety, is considerably more difficult to recognize and subsequently address. This indicates that successfully diverting offending behavior among youth involves both identification of victimized youth and appropriate interventions. Nonetheless, both tasks require the attention and collaboration of various stakeholders to successfully address victimization, psychological distress, and to divert subsequent offending. Among those crucial to this charge are: social workers, caseworkers, police and probation officers, teachers, school psychologists, judges, parents and family members, service providers, communities, and the youth themselves. Historically, approaches to diverting offending have been myopic and discrete. Focus on a singular individual (blaming the youth themselves), the family (looking to single parent’s lack of monitoring), a segment of professionals (expecting schools or police to gate keep alone), or a community (discounting neighborhoods as beyond hope), is not effective. Offending among youth is a social problem which does not occur in a vacuum; therefore, effective interventions must involve various members of society. Suggestions and implications for collaborative and multifaceted approaches are highlighted herein.

Youth, who are the intended benefactors of this research, are the obvious group to consider when attempting to identify and address victimization, psychological distress, and subsequent offending. Although apparent, it seems youth are repeatedly overlooked as a resource in guiding their own treatment; blame is often quickly ascribed while the context of youth behavior lacks attention. Many well tested theories have various strengths and weaknesses among their rationales for the etiology of youth crime; however, in the interest of focusing on what youth may be experiencing, strain theory offers a way for families, professionals, and communities to become cognizant of their needs. What children and youth face on a day- to- day basis remains a mystery for many of whom they come into contact. Examining Merton’s five adaptations of legitimate paths to success in society (Merton, 1968) may be fruitful in developing collaborative strategies for both identification and intervention. In this model, behaviors arise from innovation (youth accepts socially acceptable goals but does not use legitimate means to attain them), retreatism, (youth rejects socially acceptable goals and means of attainment), ritualism (youth accepts the socially acceptable means of goal attainment yet, the goal itself becomes lost), conformity (youth accepts both appropriate means and goals), and rebellion (youth rejects and replaces socially acceptable means and goals; developing their own system of both). With these dilemmas in mind, families, professionals, and communities can better understand a youth’s perspective of their life. Continued research employing measures to assess how and if youth feel and experience such limitations to success should include the use of related instruments such as the Accessibility Scale (Jacks, 1983) and the Awareness of Limited Opportunity Scale (Landis, Dinitz, & Reckless, 1963). Subsequent interventions based on further findings can then be aptly applied.

4.3 Future directions for research and practice

Parents and families have a unique ability to support, foster, monitor, guide, and develop positive pathways to their children’s success. They must be provided with the tools needed to be successful in this considerable task. It is not enough for parents and families to tell their children that the goal of success is found in the path of conformity, but it must also be demonstrated through their path. A fundamental component to achieving this task is in monitoring. While some parents and families may lack the ability to oversee their children as closely as they might prefer, others lack a clear understanding of the relationship between monitoring, victimization, psychological distress, and offending. As supported in this study, mothers’ support was significantly associated with psychological distress; therefore, the role of mothers is necessary in identifying and treating youth. Further, a realistic definition of what appropriate monitoring entails should involve encouraging and supporting parents in routinely checking up on their children to establish clear parameters for parental expectations (Hartinger-Saunders, 2008).

Professionals must also work together to ensure that youth are able to succeed in socially accepted paths. Various disciplines have much to learn from each other to identify and address victimization, psychological distress, and ultimately divert offending. A singular discipline cannot achieve this goal alone nor be effective without the input of others; they must work in concert and fulfill roles based on their areas of expertise. For example, social workers could apprise school administration and teachers of the importance of early intervention for explicit and circuitous victimization, such as bullying. Literature links both direct and relational victimization by peers to a number of adjustment issues; this research further confirms that direct victimization of youth has an effect on their psychological distress. Additionally, psychological distress showed a significant effect on offending over time which indicates that assessment of victimization among younger children would enhance intervention efforts and the existing literature in this area. Professionals of varying disciplines should advocate for behavioral intervention policies within school systems that are cognizant of the impact of victimization and its potential outcomes. Since large numbers of chronically victimized children and youth find themselves struggling emotionally, behaviorally, and academically, these youth will interact with various systems and professionals; they are also precisely those our interventions should be targeting. Placing youth in alternative education programs, outside ordinary school hours, and away from positive peers, is counterproductive. Current policies of this nature create unrealistic social environments which do little to prepare youth for integration into mainstream classrooms and their communities. Utilizing positive peers, adult role models, and natural environments is a better alternative for forging positive youth pathways to success thereby increasing the likelihood of maturation into productive adults.

Since findings highlight the direct effect of vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers on offending behavior (Hartinger-Saunders, 2008), targeting school systems as a context for intervention is a critical starting point. However, schools alone cannot effectively address victimization, psychological distress, and subsequent offending. Communities also play a fundamental role in youth adopting socially acceptable means and goals. For youth who may have dropped out of school, are suspended or expelled, or those who lack any formal means of intervention, the development of positive pathways may fall to communities and their peers within them. As findings support the relationship between vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers and offending at both waves, the importance of peer groups in the lives of youth is central to informing intervention strategies and promoting socially acceptable pathways.

Findings herein show a significant relationship between personal victimization, property victimization, and psychological distress which suggests that youth may view their property as extension of themselves. As property crimes most often target possessions, and not particular youth, these occurrences have the ability to impact entire communities and all of their residents. Property crime has been linked to fear of re- victimization which has been shown to elicit high degrees of anxiety, PTSD, depression, and aggressive behavior (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor, 1995). The underlying fear of potential outcomes, such as getting shot, raped, or killed, may be the common thread linking personal and property victimization to psychological distress. This indicates that it is not enough for professionals to target their strategies on youth, families, and within their realms of practice; communities as a whole must be also counted as both a place and a means for intervention. Just as vital as other stakeholders, communities have a unique ability to foster positive pathways for youth, families, and themselves. Support and development of programs that build on community strengths and empowerment have the ability to address victimization, psychological distress, and subsequent youth offending.

Reluctance or inability among professionals of any discipline to appropriately define and intervene when victimization occurs sends messages to youth that indicates socially accepted means and goals are not shared while maladaptive pathways are further reinforced. If we collectively fail to take better steps toward protecting children and youth from victimization at an early age, victims will soon graduate into our future offenders.

Table 3.

Initial Model: Exogenous Variables On Psychological Distress

| Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psych Distress On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.016 | 0.086 | 0.185 | 0.853 |

| Perception Safe | 0.003 | 0.056 | 0.047 | 0.963 |

| Parent Monitor | 0.023 | 0.046 | 0.504 | 0.614 |

| Single Parent | −0.003 | 0.040 | −0.085 | 0.932 |

| SES | 0.068 | 0.041 | 1.657 | 0.098* |

| Race | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.626 | 0.531 |

| Mom Support | −0.099 | 0.045 | −2.172 | 0.030** |

| Dad Support | −0.065 | 0.042 | −1.550 | 0.121 |

| Personal Vic | 0.103 | 0.041 | 2.475 | 0.013** |

| Property Vic | 0.087 | 0.040 | 2.157 | 0.031** |

| Vicarious: Family | 0.007 | 0.039 | 0.174 | 0.862 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.064 | 0.042 | 1.526 | 0.127 |

| Vicarious: Neigh | 0.004 | 0.071 | 0.060 | 0.952 |

p<.001,

p<.05,

p<.10

Table 4.

Initial Model: Exogenous Variables On Direct Victimization Variables

| Estimate | .E. | Est./S.E. | Two-Tailed P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Vic On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.121 | 0.083 | 1.467 | 0.142 |

| Perception Safe | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.335 | 0.737 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.100 | 0.044 | −2.254 | 0.024** |

| Single Parent | −0.050 | 0.038 | −1.309 | 0.191 |

| SES | 0.026 | 0.040 | 0.664 | 0.506 |

| Race | −0.015 | 0.040 | −0.382 | 0.702 |

| Mom Support | 0.000 | 0.044 | −0.007 | 0.995 |

| Dad Support | 0.004 | 0.041 | 0.087 | 0.931 |

| Property Vic | 0.117 | 0.038 | 3.058 | 0.002** |

| Vicarious: Family | 0.025 | 0.038 | 0.646 | 0.518 |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.228 | 0.038 | 5.972 | <.001*** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | −0.007 | 0.068 | −0.109 | 0.913 |

| Property Vic On | ||||

| Neigh Crime | 0.248 | 0.085 | 2.918 | 0.004** |

| Perception Safe | −0.049 | 0.056 | −0.888 | 0.375 |

| Parent Monitor | −0.024 | 0.046 | −0.513 | 0.608 |

| Single Parent | −0.037 | 0.040 | −0.933 | 0.351 |

| SES | −0.015 | 0.041 | −0.357 | 0.721 |

| Race | −0.023 | 0.042 | −0.544 | 0.586 |

| Mom Support | −0.030 | 0.046 | −0.652 | 0.515 |

| Dad Support | −0.007 | 0.042 | −0.155 | 0.876 |

| Vicarious: Family | 0.085 | 0.039 | 2.179 | 0.029** |

| Vicarious: Peer | 0.131 | 0.040 | 3.267 | 0.001** |

| Vicarious: Neigh | −0.106 | 0.070 | −1.505 | 0.132 |

p<.001,

p<.05,

p<.10

Highlights.

Personal, vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers, and perception of neighborhood safety were significant predictors of offending at wave 1.

Personal and property victimization were significant predictors of psychological distress.

Psychological distress did not have a significant relationship with offending at wave 1 yet, it did at wave 2.

Vicarious victimization by exposure to violence among peers and offending at wave 1 were all significant predictors of offending at wave 2.

Acknowledgments

Research support

The original BLSYM was supported by a five year grant (# RO1 AA08157) through the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Zhang, et al., 2001).

The Authors would like to acknowledge and thank colleagues at Georgia State University; Peter Lyons, Deborah Whitley and Fred Brooks for their support and assistance in proofreading subsequent drafts throughout manuscript preparation.

Appendix A

Delinquency: Total Delinquent Acts

Thirty-four items asking how many times the respondent committed the following delinquent acts in the last 12 months:

Stolen or tried to steal a motor vehicle such as a car or motorcycle

Stolen or tried to steal something worth more than US$100

Purposely set fire to a building, a car, or other property, or tried to do so

Attacked someone with the idea of seriously hurting or killing that person

Involved in gang fights

Had or tried to have sexual relations with someone against their will

Used force or strong-arm tactics to get money or things from people

Broken or tried to break into a building or vehicle to steal something or just look around

Driven a motor vehicle while feeling the effects of alcohol

Had a motor vehicle accident and left the scene without letting the other person know about the accident

Purposely damaged or destroyed property belonging to someone you live with

Purposely damaged or destroyed property that did not belong to you or someone you live with

Knowingly bought, sold, or held stolen goods, or tried to do any of these things

Carried a hidden weapon

Stolen or tried to steal things worth US$100 or less

Been paid for having sexual relations with someone

Used checks illegally to pay for something, or used intentionally overdrafts

Sold marijuana or hashish

Hit or threaten to hit anyone other than the people you live with

Sold hard drugs other than marijuana or hashish

Tried to cheat someone by selling them something that was worthless or not what you said it was

Avoided paying for such things as food, movies, or bus or subway rides

Used or tried to use the credit cards of someone you didn’t live with, without the owner’s permission

Made obscene telephone calls

Snatched someone’s purse or wallet or picked someone’s pocket

Embezzled money

Paid someone to have sexual relations with you

Stolen money or other things from someone you live with

Stolen money, goods, or property from the place you work

Hit or threatened to hit someone you live with

Been very loud, rowdy, or unruly in a public place

Taken a vehicle for a ride without the owner’s permission

Begged for money or things from strangers

Used or tried to use the credit cards of someone you live with, without permission

Footnotes

Financial disclosure/conflict of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Robin M. Hartinger-Saunders, Email: rsaunders@gsu.edu.

Barbara Rittner, Email: Rittner@buffalo.edu.

William Wieczorek, Email: wieczowf@buffalostate.edu.

Thomas Nochajski, Email: thn@buffalo.edu.

Christine M. Rine, Email: cmrine@plymouth.edu.

References

- Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, Longworth SL, McClelland GM, Dulcan MK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:403–410. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attar B, Guerra N, Tolan P. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban, elementary school students. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Farrell M. Parental support and control as predictors of adolescent drinking, delinquency and related problem behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:763–776. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G, Welte J, Hoffman J, Dintcheff B. Gambling and alcohol use among youth influences of demographic, socialization and individual factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(6):749–767. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baren SW. Street youth violence and victimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2003;4(1):22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Psychosocial sequelae of violent victimization in a national youth sample. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(5):726–736. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet J, Boss MW. Reliability and validity of the brief symptom inventory. Psychological Assessments. 1991;3(33):433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M. Adolescents who witness community violence: Can parent support and prosocial cognitions protect them from committing violence? Child Development. 2005;76(4):917–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Chen J, Brownson R. The role of repeat victimization in adolescent delinquent behaviors and recidivism. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;32:272–280. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman HC, Jenson JM. A longitudinal investigation of delinquency among abused and behavior problem youth following participation in a family preservation program. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2000;31:143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Loeber R. Adolescent marijuana and alcohol use: The role of parents and peers revisited. American Journal of Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11(1–2):11–25. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. Maltreatment by parents and peers: The relationship between child abuse, bully victimization and psychological distress. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4(1):45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in a Danish national youth probability sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):174–180. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug abuse. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Cross T, Cantor E. The justice system for juvenile victims: A comprehensive model of case flow. Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2005;6(3):83–102. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Boldizar JP. The prevalence and consequences of exposure to violence among African American youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:429–430. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers A, Lanclos N, Kelly M. Validation of a screening instrument for exposure to violence in African American children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27(4):351–361. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Kostelny K, Dubrow N. What children can tell us about living in danger. American Psychologist. 1991;46:376–383. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutterman N, Cameron M. Assessing the impact of community violence on children and youth. Social Work. 1997;42(5):495–505. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartinger-Saunders R. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University at Buffalo; New York: 2008. Victimization as a predictor of offending behavior in youth. [Google Scholar]

- Jacks I. Accessibility scale [AcS] In: Brodsky S, Smitherman H, editors. Handbook of scales for research in crime and delinquency. NY: Plenum; 1983. pp. 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Kotch J, Catellier D, Winsor J, Dufort V, Hunter W, Amaya-Jackson L. Adverse behavioral and emotional outcomes from child abuse and witnessed violence. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:179–186. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Mejia R, Torres deG, Angold A. Exposure to violence against a family member and internalizing symptoms in Columbian adolescent: The protective effects of family support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69 (6):971–982. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koposov RA, Ruchkin VV, Eisemann M. Sense of coherence: A mediator between violence exposure and psychopathology in Russian juvenile delinquents. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2003;191:638–644. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000092196.48697.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Dinitz S, Reckless WC. Awareness of limited opportunity scales [ALOS] In: Brodsky S, Smitherman H, editors. Handbook of scales for research in crime and delinquency. NY: Plenum; 1963. pp. 581–584. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. How families and communities influence youth victimization. Washington D. C: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Kalb L, Huizinga D. Juvenile Delinquency and Serious Injury Victimization. Washington D. C: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lorion R, Saltzman W. Children’s exposure to community violence: Follow a path from concern to research to action. Psychiatry. 1993;56:55–65. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D, Krull J, Lockwood C. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maschi T. Unraveling the link between trauma and male delinquency: Cumulative versus differential risk perspectives. Social Work. 2006;51(1):59–70. doi: 10.1093/sw/51.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza J, Overstreet S. Children and adolescent exposed to community violence: A mental health perspective for school psychologists. School Psychology Review. 2000;29(1):86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Social theory and social structure. New York: The Free Press/Macmillan; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman R, Stueve A. Normalization of violence among inner-city youth: A formulation for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:92–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofziger S. Violent lives: A lifestyle model linking exposure to violence to juvenile violent offending. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2005;42(1):3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal BS, Wilson C, Futch V. Trauma, protection, and distress in late adolescence: A multi-determinant approach. Adolescence. 2009;44(176) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: testing social-disorganization theory. The American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer JN, Ruback RB. Violent victimization as a risk factor for violent offending among juveniles. Washington D. C: U. S. Department of Justice; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone M, Ayers T, Kasprow W, Voyce C, Barone C, Shriver T, Weissberg RP. No safe haven: A study of violence exposure in an urban community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1343–1352. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN, Sickmund M. Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 national report. Washington DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2006. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED495786) [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WC, Rosenthal B. The relationship between exposure to community and psychological distress among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Violence and Victims. 2003;18(3):335–352. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Barnes G, Hoffman J, Wieczorek W, Zhang L. Substance involvement and the trajectory of criminal offending in young males. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:267–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Wieczorek W. Alcohol, intelligence and violent crime in young males. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10(3):309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte J, Zhang L, Wieczorek W. The effects of substance use on specific types of criminal offending in young men. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38 (4):416–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte J, Wieczorek W. The Influence of Parental Drinking and Closeness on Adolescent Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(2) doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte J, Wieczorek W. Deviant lifestyle and crime victimization. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2001;29(2):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte J, Wieczorek W. Youth gangs, drug use and delinquency. Journal of Criminal Justice. 1999;27(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Wieczorek W, Welte J. Underlying common factors of adolescent problem behaviors. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2002;29(2):161–182. [Google Scholar]