Abstract

Background

Obesity is increasing in prevalence and is a major contributor to worldwide morbidity. One consequence of obesity might be an increased risk for periodontal disease, although periodontal inflammation might, in turn, exacerbate the metabolic syndrome, of which obesity is one component. This review aims to systematically compile the evidence of an obesity–periodontal disease relationship from epidemiologic studies and to derive a quantitative summary of the association between these disease states.

Methods

Systematic searches of the MEDLINE, SCOPUS, BIOSIS, LILACS, Cochrane Library, and Brazilian Bibliography of Dentistry databases were conducted with the results and characteristics of relevant studies abstracted to standardized forms. A meta-analysis was performed to obtain a summary measure of association.

Results

The electronic search identified 554 unique citations, and 70 studies met a priori inclusion criteria, representing 57 independent populations. Nearly all studies matching inclusion criteria were cross-sectional in design with the results of 41 studies suggesting a positive association. The fixed-effects summary odds ratio was 1.35 (Shore-corrected 95% confidence interval: 1.23 to 1.47), with some evidence of a stronger association found among younger adults, women, and non-smokers. Additional summary estimates suggested a greater mean clinical attachment loss among obese individuals, a higher mean body mass index (BMI) among periodontal patients, and a trend of increasing odds of prevalent periodontal disease with increasing BMI. Although these results are highly unlikely to be chance findings, unmeasured confounding had a credible but unknown influence on these estimates.

Conclusions

This positive association was consistent and coherent with a biologically plausible role for obesity in the development of periodontal disease. However, with few quality longitudinal studies, there is an inability to distinguish the temporal ordering of events, thus limiting the evidence that obesity is a risk factor for periodontal disease or that periodontitis might increase the risk of weight gain. In clinical practice, a higher prevalence of periodontal disease should be expected among obese adults.

Keywords: Body weight, obesity, overnutrition, periodontal diseases, review

The worldwide prevalence of obesity is a considerable source of concern given its potential impact on morbidity, mortality, and the cost of health care.1 The World Health Organization (WHO)2 has recognized obesity as a predisposing factor to major chronic diseases ranging from cardiovascular disease to cancer. Successful efforts to reduce and prevent obesity will have substantial public-health benefits.

Chronic periodontal disease is an inflammatory condition characterized by a shift in the microbial ecology of subgingival plaque biofilms and the progressive host-mediated destruction of tooth-supporting structures.3–5 There has been considerable interest in drawing connections between periodontal inflammation and other chronic conditions, notably heart disease,6,7 diabetes,8 and preterm low birth weight delivery.9 Although observed associations suggested a causal role for periodontitis in certain systemic diseases, a consensus opinion demands further evidence.10,11

Obesity might represent a systemic condition capable of influencing the onset and progression of periodontal disease. First noted using a ligature-induced periodontitis model in the rat,12 the evidence of an obesity–periodontitis link in humans was recently addressed in several reviews.13–20 Most of these publications13–19 described a relationship between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome (MetS) of which obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension represent components,21 as extensively discussed by Bullon et al.15 In brief, all MetS components derive from a proinflammatory state characterized by insulin resistance and oxidative stress, with the latter being a common link with periodontitis in a bidirectional relationship.15 Products of oxidative damage22 and advanced glycation end products23 might promote periodontal disease. Meanwhile, periodontitis could, itself, be a source of oxidative stress,24,25 perhaps through the alteration of levels of circulating adipocytokines such as leptin,26 which, in turn, accelerate the onset of insulin resistance and MetS.

Although these reviews provided insight into the possible mechanisms of an obesity–periodontitis relationship, none of the reviews were systematic or quantitative, and none of them performed a quality assessment of included studies. There has been a tendency to highlight a relatively small pool of studies specific to obesity and periodontitis rather than to explore the broader base of anthropometric data collected during epidemiologic studies. This systematic review aims to compile the evidence for an obesity–periodontal disease association and, through a meta-analysis, to summarize individual study results into a quantitative estimate of that relationship. We hypothesized that there was a difference in the prevalence of obesity in the general adult population across groups of individuals with or without current signs of periodontal disease. As secondary aims, we sought to characterize mean differences in obesity parameters across groups with or without periodontal disease, mean differences in periodontal disease parameters across obese and non-obese groups, and any linear changes in periodontal prevalence with an increasing body mass index (BMI).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search

Electronic searches of the MED-LINE, SCOPUS, BIOSIS, LILACS, Cochrane Library, and Brazilian Bibliography of Dentistry databases were conducted in July 2010 for publications that investigated periodontal disease and obesity. In MED-LINE, the Medical Subject Heading term periodontal disease and the Boolean connector AND were linked to the terms overweight, overnutrition, BMI, waist-hip ratio, waist circumference, body weight, and body weight changes, each joined by the connector OR with vocabulary exploding allowed to automatically query indexed subheadings under the main terms. Analogous search strategies were applied to other databases, expanding query components to include similar terms such as periodontal and periodontitis to account for less-controlled indexing vocabularies. Terms were in English, but no other language or date restrictions were placed. Two reviewers (BWC and SJW) appraised retrieved titles and abstracts. Exclusion criteria included: non-human studies, no measure of periodontal disease or obesity, case series, studies of children, reviews, abstracts, or lack of peer review. Full-text copies of the remaining potentially relevant citations were obtained, and the following inclusion criteria were applied: English or Spanish language (or translation), suitable reference group, and an obesity–periodontitis association reported or calculable from tables. Publications were further excluded if periodontal status was only assessed by tooth loss, oral hygiene, gingival appearance, or use of a dental prosthesis. Additional publications were obtained by searching the citation listings of included studies and review articles.13–20 Articles meeting the inclusion criteria were combined with the articles obtained from the electronic search. Each reviewer was then unmasked to the other’s progress and a consensus was reached regarding any citations selected by only one reviewer.

Quality of Evidence

The quality of the information abstracted for the meta-analysis was assessed using a scale designed specifically for this review by the authors. Each reviewer scored studies independently using 24 criteria across six domains as follows: research questions (14 points), study design (nine points), measurement (eight points), analysis (14 points), presentation (four points), and conflict of interest (four points). A total of 16 points across the design and analysis domains were dedicated to appropriate adjustment for confounding factors. Quality-of-evidence scores were not intended to rank studies based on intrinsic quality alone but, rather, according to how well study results estimated the association between obesity and periodontal disease in the general population. There was no statistically significant difference in quality scores by reviewer (mean difference: 0.8 points; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test; P = 0.68); therefore, studies were ranked by the average score. The empirical distribution of quality scores suggested three strata, which roughly partitioned studies in tertiles. Twelve of the 13 high-quality studies and eight of the 10 low-quality studies maintained their respective designation regardless of whether average scores or the scores of either reviewer were used for classification. Two very low quality studies of the 10 were not included, and therefore did not contribute to the results of the review.

Meta-Analysis

The prevalence odds ratio was the measure abstracted for the primary meta-analysis because nearly all studies were cross-sectional. When individual studies reported more than one association measure, adjusted measures were preferred over crude measures, and stratified results were pooled when possible to estimate a population-level effect. When multiple publications drew results from an identical set of participants (such as from large national surveys), only data from the study with the most inclusive study population were abstracted.

Periodontal disease status was based on the clinical parameters selected by the individual studies. If multiple measures of periodontal disease appeared in a single study, clinical attachment loss (AL) was preferred to the probing depth, which was preferred to radiographs. Presented with multiple definitions, BMI ≥30 kg/m2, concordant with guidelines of the WHO,1 was the preferred measure of obesity. The waist-to-hip ratio was considered in the case of one study that did not report BMI. Given alternate cut points, the highest reported BMI category defined obesity, and the second highest category defined overweight. Given multiple categories of periodontal disease, the most severe disease designation was preferred unless few subjects (<20) were present in that uppermost stratum.

Overall and subgroup Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effects27 summary odds ratios (sORs) were obtained using statistical software.‡ Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by the method of Shore et al.28 (Shore-corrected 95% CI) whenever this adjustment resulted in more conservative (wider) CIs. An overall DerSimonian-Laird random-effects29 sOR was calculated for comparison. The sensitivity of the sOR to the inclusion or exclusion of individual studies was assessed.As a secondary meta-analysis, from studies that presented a difference in mean BMI across groups with and without periodontal disease or for those presenting a difference in mean clinical AL across obese and non-obese groups, a fixed-effects summary mean difference (sMD) was calculated using the general variance inverse-weighting method.30 If not reported, SDs were calculated or estimated to obtain sMD. A Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effects linear sOR was calculated from studies that reported a change in the odds of periodontal disease per unit increase in BMI.

For the primary meta-analysis, a funnel plot served as a visual means for assessing any disproportionate representation of study results according to strength and precision.31 A Begg-adjusted rank correlation test32 formally tested for any trend of increasing association strength with reducing precision. It was suggested that such an effect could represent the preferential publication of statistically significant positive results,33 which could bias the sOR. The rank-based data-augmentation technique of Duval and Tweedie,34 commonly called the trim-and-fill method, was used to recalculate the sOR under the hypothetical scenario that association measures of similarly low precision but opposite direction had also been present. Studies were divided into subgroups based on features of study designs or characteristics of study populations to explore whether the sOR was sensitive to such variables.

RESULTS

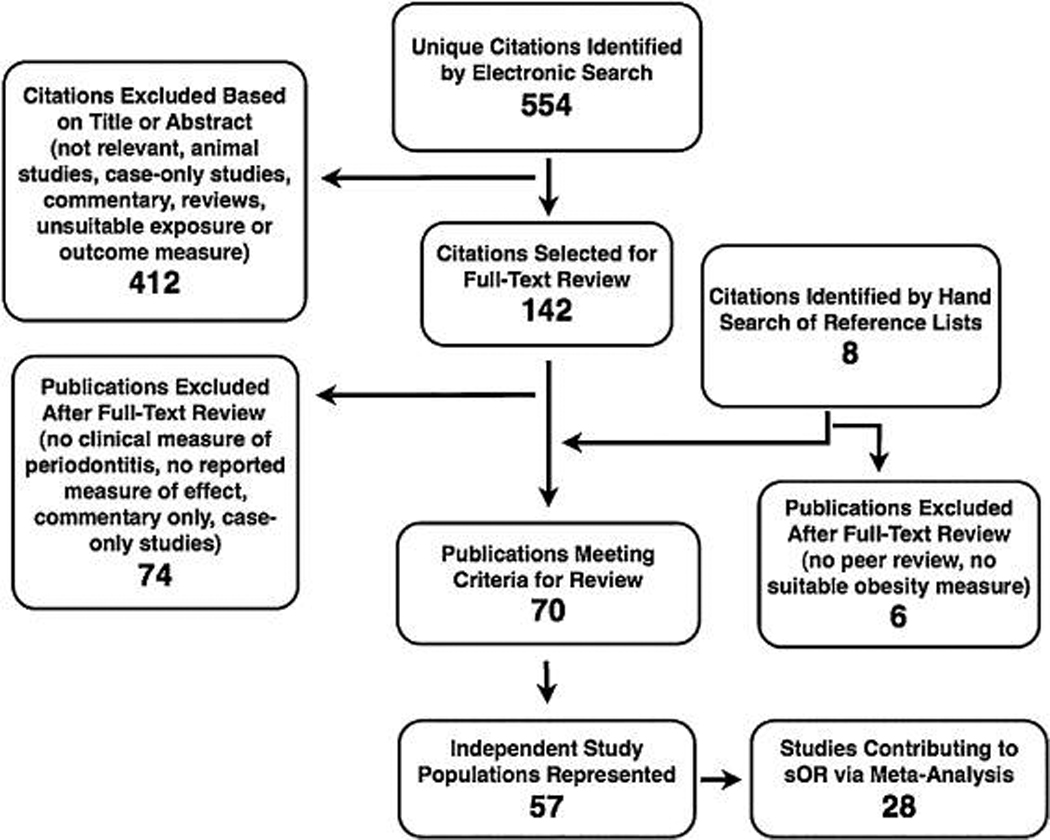

The electronic search generated 864 hits, which represented 554 unique citations. A total of 142 publications were obtained as full-text copies, and 74 of these publications were later excluded on the basis of a priori criteria. Eight additional publications were identified as potentially relevant among the citation listings of included articles and review articles, and six of these articles were later excluded based on the same criteria. In total, 70 publications that represented 57 unique study populations were included for systematic review.35–104 A summary flowchart is presented in accordance with a proposal for reporting meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology105 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Quality in reporting of observational studies in an epidemiology flowchart.

Articles35,36,39–41,45,49,54,56,57,59,61–64,67,68,72,74,77, 82,84,90,92,95–97,101 listed in Table 1 represent the study results that contributed to the calculation of the sOR. Tables 2 through 4 lists those results37–39,41–43,46–48, 50–52,57,60,63–66,69–72,76,78–80,84–86,90,94,98,99,101,102 that did not define periodontal disease and obesity as binary conditions but could contribute to an sMD (Tables 2 and 3) or linear sOR (Table 4). Table 5 lists four studies53,73,98,103 that were unique in design and therefore their results could not be pooled. Two studies75,91 were excluded from the review because of low scores according to the quality-of-evidence criteria. Results from 12 studies39,41,52,57,63,64,72,84,90, 98,101,102 appear more than once across Tables 1 through 5, as do three pairs of separately published studies in which each pair was based on a single study population.36,37,58,59,72,73 Only independent results contributed to any summary measure. An additional 11 studies,44,55,58,81,83,87–89,93,100,104 which otherwise matched the inclusion criteria but derived results from subsets of the populations already described in Tables 1 through 5, are not listed. No experimental studies were found, and just two studies73,98 were prospective. Publications were written in English, and no study published before the year 1999 met the inclusion criteria. Calculating a measure of association between periodontal disease and obesity or MetS was a principle study aim of 24 publications.35,36,43,45,47–49,54,57,59,63,64,66–68,72,73,82,84–86, 90,101,103 Forty-one independent results reported a positive association,35,36,39–43,45–49,51,54,56–58,60,62,63, 66–70,72,74,76,78,80,82,84–86,90,92,94,95,97,99,100 22 of which were statistically significant (P <0.05).36,39,41,43, 48,49,54,56–58,63,66,72,74,80,82,85,86,90,94,97,99

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics and Individual Results of Studies Meeting Criteria for Systematic Review: Results Contributing to the sOR

| Reference | Study Population |

Periodontal Disease Case Definition |

Obesity Case Definition |

Crude POR (95% CI) |

Adjusted POR (95% CI) |

Quality of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabdulkarim et al., 200535 | 400 dental clinic patients near Cleveland, OH | Alveolar bone score <60 | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 2.37 (1.55 to 3.63) | 1.86 (0.99 to 3.51) | Medium |

| Al-Zahrani et al., 200336 | 13,665 NHANES III adults | ≥1 site with clinical AL ≥3 mm and PD ≥4 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.64 (1.38 to 1.96) | 1.37 (1.14 to 1.64) | High |

| Bouchard et al., 200639 | 2,132 NPASES I subjects aged 35 to 65 years in France | ≥1 site with clinical AL >5 mm | BMI >30 kg/m2 | 2.2 (1.7 to 3.0) | — | Medium |

| Brennan et al., 200740 | 1,256 postmenopausal women near Buffalo, NY | Mean radiographic alveolar crest height loss >3 mm or ≥2 sites with clinical AL >5 mm or tooth loss due to periodontitis | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.20 (0.87 to 1.67) | — | Low |

| Buhlin et al., 200341 | 50 prevalent periodontitis cases and 47 convenience controls inSweden | ≥7 sites with clinical AL >5 mm | BMI >26 kg/m2 (men) BMI >25 kg/m2 (women) |

— | 4.54 (1.59 to 13.0) | Medium |

| Dalla Vecchia et al., 200545 | 706 non-pregnant community adults aged 30 to 65 years in southern Brazil | ≥30% of teeth with clinical AL ≥5 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.35 (0.97 to 1.9) | 1.43 (0.92 to 2.22) | High |

| El-Sayed Amin, 201049 | 380 patients aged 20 to 26 years attending an obesity clinic in Egypt | CPI ≥ 3 | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 2.89 (1.65 to 5.04) | — | Low |

| Furuta et al., 201054 | 2,225 non-smoking university freshmen in Japan | ≥1 tooth with PD >3 mm | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 2.54 (1.47 to 4.39) | 3.4 (2.1 to 5.51) | High |

| Griffin et al., 200956 | 10,505 NHANES 1999 through 2004 adults | Examiner diagnosis | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | — | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.41) | Medium |

| Haffajee and Socransky, 200957 | 695 adult periodontal clinic patients near Boston, MA | ≥5% sites with clinical AL ≥4 mm or PD ≥4 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 5.31 (2.79 to 9.5) | 2.31 (1.19 to 4.49) | High |

| Han et al., 201059 | 1,046 community adults aged 15 to 84 years in Sihwa and Banwol, South Korea | CPI ≥3 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | — | 1.60 (1.13 to 2.25) | High |

| Hayashida et al., 200961 | 135 community adults aged 41 to 91 years near Nagasaki, Japan | CPI = 4 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 0.63 (0.27 to 1.44) | — | Low |

| Ide et al., 200762 | 4,285 civil officers Aged 40 to 59 years in Japan | CPI = 4 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 1.24 (0.98 to 1.57) | — | Medium |

| Khader et al., 200963 | 340 patient Companions at a Jordanian medical clinic | ≥1 site with clinical AL ≥3 mm and PD ≥4 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 6.6 (3.5 to 12.5) | 2.9 (1.3 to 6.1) | High |

| Kongstad et al., 200964 | 1,504 Copenhagen City Heart Study participants, Denmark | Mean clinical AL ≥3 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.94 (1.36 to 2.76) | 0.60 (0.36 to 0.99) | High |

| Kushiyama et al., 200967 | 1,070 community Adults aged 40 to 70 years in Miyazaki City, Japan | CPI = 4 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.64) | 1.09 (0.77 to 1.53) | High |

| Linden et al., 200768 | 1,362 men aged 60 to 70 years near Belfast, Ireland | ≥15% sites with clinical AL ≥6 mm and ≥1 site with PD ≥6 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.68 (0.94 to 3.0) | 1.55 (0.82 to 2.93) | High |

| Morita et al., 200972 | 2,475 employees of a large company in Tokyo, Japan | CPI ≥3 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) | High |

| Nishida et al., 200574 | 372 factory workers Near Osaka, Japan | Upper 20th percentile by percentage of sites with PD >3.5 mm | BMI ≥28 kg/m2 | 3.17 (1.79 to 5.61) | 4.40 (1.18 to 16.4) | Medium |

| Ojima et al., 200677 | 3,343 1999 National Nutrition Survey and Survey of Dental Diseases participants in Japan | CPI = 4 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.25) | 1.00 (0.79 to 1.26) | High |

| Saito et al., 200182 | 643 dentate adults near Fukuoka, Japan | ≥1 tooth with PD ≥4 mm | WHR >0.8 (men) WHR >0.9 (women) |

— | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.9) | Low |

| Saito et al., 200584 | 584 community women aged 40 to 79 years in Hisayama, Japan | Mean clinical AL >2.41 mm | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.8) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.4) | Medium |

| Shimazaki et al., 201090 | 1,160 dentate adults Aged 20 to 77 years at a health clinic in Fukuoka, Japan | ≥3 sextants with CPI ≥3 | Highest BMI quintile (median: 26.5 kg/m2) compared to lowest BMI quintile (median: 18.3 kg/m2) | 3.90 (2.24 to 6.78) | 2.42 (1.33 to 4.42) | High |

| Slade et al., 200392 | 5,552 Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study in United States subjects aged 52 to 74 years | ≥30% of sites with PD ≥4 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.29 (0.93 to 1.79) | — | Low |

| Torrungruang et al., 200595 | 2,005 electric workers aged 50 to 73 years near Bang Kruai, Thailand | Mean clinical AL ≥4 mm | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.7) | — | Low |

| Wakai et al., 199996 | 630 adults aged 23 to 83 years presenting for health tests in Japan | CPI = 4 | Highest BMI quintile (>26 kg/m2) compared to lowest BMI quintile (<20 kg/m2) | 1.15 (0.49 to 2.70) | 0.95 (0.50 to 1.81) | High |

| Wang et al., 200997 | 12,076 community adults aged 35 to 44 years near Keelung, Taiwan | CPI ≥3 | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.38) | — | Low |

| Wood and Johnson, 2008101 | 213 non-smoking dental-clinic patients in Mississippi | Mean PSR = 3 | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | — | 4.38 (0.88 to 21.8) | Low |

POR = prevalence odds ratio; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (United States); PD = probing depth; NPASES I = First National Periodontal and Systemic Examination Survey (France); — = data not provided; CPI = Community Periodontal Index; WHR = waist-to-hip ratio; PSR = periodontal screening and recording.

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics and Individual Results of Studies Meeting Criteria for Systematic Review That Compared Mean Obesity Parameters Across Periodontal Disease Cases and Controls

| Periodontal Disease | Crude Mean BMI (kg/m2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Study Population | Case Definition | Cases | Controls |

| Al-Zahrani et al., 200537 | 2,521 adults from NHANES III with similar physical activity levels over 10 years | ≥1 site with clinical AL ≥3 mm and PD ≥4 mm | 26.6 (SE: 0.3) | 25.8 (SE: 0.2); P = 0.04* |

| Buhlin et al., 200341 | 50 prevalent periodontitis cases and 47 convenience controls in Sweden | ≥7 sites with >5 mm clinical AL | 25.7 (SD: 3.3) | 24.1 (SD: 3.0); P = 0.01 |

| Buhlin et al., 200942 | 68 prevalent periodontitis cases and 48 community controls in Sweden | ≥7 sites with >5 mm clinical AL | 25.9 (SD: 3.5) WHR: 0.90 (SD: 0.08) |

25.0 (SD: 4.1); P = 0.20 WHR: 0.89 (SD: 0.11) |

| Dietrich et al., 200646 | 462 male United States veterans aged 47 to 92 years | ≥1 site with PD >4 mm | 27.8 (SD: 3.6) | 27.3 (SD: 3.8); P = 0.27 |

| Franek et al., 200950 | 99 patients with essential hypertension in Poland | CPI ≥ 3 | 29.5 (SD: 4.4) | 29.9 (SD: 4.8); P = 0.63 |

| Furugen et al., 200851 | 158 community adults aged 76 years in Japan | ≥1 tooth with PD >5 mm | 22.8 (SD: 2.7) | 22.4 (SD: 2.6); P = 0.38 |

| Furuichi et al., 200352 | 1,068 community adults aged 40 years and older in Japan | CPI = 4; controls CPI <3 | 23.6 (SD: 2.9) | 23.6 (SD: 3.0); P = 1.0 |

| Haffajee and Socransky, 200957 | 695 adult periodontal clinic patients near Boston, MA | ≥5% sites with clinical AL ≥4 mm or PD ≥4 mm | 27.9 (SD: 5.7) | 24.7 (SD: 5.6); P <0.005 |

| Hattatoglu-Sönmez et al., 200860 | 45 premenopausal female periodontal patients without diabetes and 40 convenience controls in Turkey | Patient referred to periodontal clinic for treatment | 27.2 (SD: 5.0) | 25.1 (SD: 3.6); P = 0.06 |

| Kshirsagar et al., 200765 | 154 hemodialysis patients in New York and North Carolina | ≥60% with clinical AL ≥4 mm | 27.2 (SD: 6.6) | 28.8 (SD: 7.7); P = 0.27 |

| Kumar et al., 200966 | 513 mine laborers aged 18 to 54 years in India; no participants with BMI >30 kg/m2 | CPI ≥3 | 24.2 (SD: 3.4) | 20.8 (SD: 2.8); P <0.005 |

| Loos et al., 200069 | 54 dental clinic patients in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, with generalized periodontitis and 43 controls | ≥8 teeth with radiographic bone loss into middle third of root length | 24.2 (SD: 3.8) | 23.6 (SD: 2.9); P = 0.39 |

| Machado et al., 200570 | Convenience sample of 60 dental-clinic patients, students, and staff in Brazil | ≥2 sites with ≥5 mm PD | 25.0 (SD: 3.3) | 24.4 (SD: 2.6); P = 0.43 |

| Morita et al., 200972 | 2,475 employees of a large company in Tokyo, Japan | CPI ≥3 | 24.0 (SD: 3.1) | 22.9 (SD: 3.1); P <0.005 |

| Noack et al., 200176 | 174 community adults aged 35 to 79 years near Buffalo, NY | Mean clinical AL >3 mm; controls with mean clinical AL of 0 to 2 mm | 28.9 (SD: 5.3) | 27.5 (SD: 5.3); P = 0.17 |

| Phipps et al., 200778 | Community sample of 1,210 dentate men in the U.S. aged ≥65 years | Clinical AL ≥5 mm in ≥30% of teeth | 27.3 | 27.2; P = 0.58 |

| Pitiphat et al., 200679 | 35 pregnant women with periodontitis and 66 controls near Boston, MA; prepregnancy BMI collected | ≥1 site with ≥3 mm alveolar bone loss | 23.0 (SD: 5.1) | 24.3 (SD: 4.1); P = 0.17 |

| Pitiphat et al., 200880 | Convenience sample of 121 adults presenting for oral examinations in Thailand | >30% of sites with PD ≥5 mm | 23.8 (SD: 3.2) | 21.6 (SD: 2.4); P <0.005 |

| Saito et al., 200584 | 584 community women aged 40 to 79 years in Hisayama, Japan | Mean clinical AL >2.41 mm | 23.6 (SD: 3.1) | 23.0 (SD: 3.5); P = 0.09 |

| Saito et al., 200885 | 34 female periodontitis cases and 42 controls aged 50 to 59 years in ≥3 Hisayama, Japan | ≥1 tooth with PD >5 mm and/or at least three teeth with PD >3 mm | 23.3 (SD: 2.6) WHR: 0.89 (SD: 0.07) |

21.9 (SD: 3.2); P = 0.01 WHR: 0.89 (SD: 0.06); P = 0.92 |

| Shimazaki et al., 201090 | 1,160 dentate adults aged 20 to 77 years at a health clinic in Fukuoka, Japan | ≥3 sextants with CPI ≥3 | Median 22.8 | Median: 21.7; P <0.005 |

| Söder et al., 200694 | 33 periodontitis patients and 31 controls selected from an ongoing study in Sweden | ≥1 site with PD ≥5 mm | 25.9 (SD: 5.2) | 23.5 (SD: 3.0); P = 0.03 |

| Weyent et al., 200498 | 1,053 U.S. community adults aged ≥65 years at baseline | ≥10% of sites with PD ≥6 mm | 26.6 (SE: 0.6) | 27.2 (SE: 0.2); P = 0.31 |

| Wolff et al., 200999 | 59 periodontitis cases and 53 controls free of diabetes recruited from a dental clinic in Minneapolis, MN | ≥5 teeth with PD ≥5 mm | 27.6 (SD: 4.6) | 25.5 (SD: 4.6); P = 0.02 |

| Wood and Johnson, 2008101 | 213 dental clinic patients in Mississippi | Mean PSR = 3 | Non-smokers: 29.2 (SE: 1.0) Smokers: 26.2 (SE: 0.6) | Non-smokers: 25.3 (SE: 0.6); P = 0.01 Smokers: 26.6 (SE: 1.4); P = 0.78 |

| Xiao et al., 2009102 | 492 clinic patients aged 40 to 87 years in China | ≥30% of sites with clinical AL ≥3 mm | Patients with diabetes: 24.1 (SD: 3.5) Patients without diabetes: 22.3 (SD: 2.8) | Patients with diabetes: 24.2 (SD: 5.5); P = 0.80 Patients without diabetes: 22.8 (SD: 4.0); P = 0.29 |

POR = prevalence odds ratio; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (United States); PD = probing depth; WHR = waist-to-hip ratio; CPI = Community Periodontal Index; PSR = periodontal screening and recording.

P value for mean differences calculated by the unpaired t test.

Table 4.

Descriptive Characteristics and Individual Results of Studies Meeting Criteria for Systematic Review that Presented a Relative Increase in the Odds of Periodontal Disease With Each Unit Increase in BMI

| Reference | Study Population | Periodontal Disease Case Definition |

Adjusted POR for Obesity With Each Unit Increase in BMI (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Zahrani et al., 200537 | 2,213 adults from NHANES III with a 10-year history of similar physical activity levels | ≥1 site with PD ≥4 mm and clinical AL ≥3 mm | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.05) |

| Borges-Yáñez et al., 200638 | 315 community adults aged ≥60 years in Mexico | Clinical AL ≥4 mm | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.05) |

| Bouchard et al., 200639 | 2,132 participants in NPASES I aged 35 to 65 years | ≥1 site with PD ≥4 mm and clinical AL ≥3 mm | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.07) |

| Ekuni et al., 200848 | Convenience sample of 618 students at Okayama University, Japan; none of the subjects had a BMI >30 kg/m2 or a CPI >3 | CPI = 3 | 1.16 (1.03 to 1.31) Crude: 1.17 (1.04 to 1.31) |

| Furuichi et al., 200352 | 1,068 community adults aged ≥40 years in Japan | CPI = 4 | 0.94 (0.81 to 1.09) Crude: 1.03 (0.91 to 1.17) |

| Marugame et al., 200371 | 664 men aged 46 to 57 years at a self-defense force preretirement exam in Japan | Lowest 30% in distribution of mean alveolar bone support compared to highest 30% in distribution of mean alveolar bone support | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.09) Crude: 0.94 (0.87 to 1.02) |

| Shimazaki et al., 201090 | 1,160 dentate adults aged 20 to 77 years at a health clinic in Fukuoka, Japan | ≥3 sextants with CPI ≥3 | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.16) |

| Xiao et al., 2009102 | 492 clinic patients aged 40 to 87 years in China | ≥30% of sites with clinical AL ≥3 mm | Patients with diabetes: 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) Patients without diabetes: 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) |

POR = prevalence odds ratio; NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (United States); PD = probing depth; NPASES I = First National Periodontal and Systemic Examination Survey (France); CPI = Community Periodontal Index.

Table 3.

Descriptive Characteristics and Individual Results of Studies Meeting Criteria for Systematic Review That Compared Mean Periodontal Disease Parameters Across Obese and Non-Obese Groups

| Obesity Case | Crude Mean Clinical AL (mm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Study Population | Definition | Cases | Controls |

| Chapper et al., 200543 | Convenience sample of 60 patients with gestational diabetes in Brazil | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 2.61 (SE: 0.41) | 2.21 (SE: 0.54); P = 0.03 |

| Dumitrescu and Kawamura, 201047 | Convenience sample of 79 private-practice patients | BMI ≥25 kg/m2 | 3.18 (SD: 1.04) | 3.07 (SD: 1.42); P = 0.70 |

| Khader et al., 200963 | 340 patient companions at a Jordanian medical clinic | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 3.03 (SD: 1.14) | 2.27 (SD: 0.77); P <0.005 |

| Kongstad et al., 200964 | 1,504 participants in the Copenhagen City Heart Study, Denmark | BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | Women: 2.93 (SD: 1.39) Men: 3.18 (SD: 1.73) | Women: 2.39 (SD: 0.93); P <0.005 Men: 2.68 (SD: 1.20); P <0.005 |

| Sarlati et al., 200886 | 40 obese cases aged 18 to 34 years and 40 controls in Iran | Not stated | 1.98 (SD: 0.5) | 1.63 (SD: 0.3); P <0.005 |

Table 5.

Descriptive Characteristics and Individual Results of Studies Meeting Criteria for Systematic Review That Had Other Study Designs

| Reference | Study Population and Design | Primary Study Result |

|---|---|---|

| Furukawa et al., 200753 | Cross-sectional study of 94 hospital outpatients with type 2 diabetes in Japan | Adjusted for confounders; Spearman correlation coefficients between BMI and mean PD: −0.071; P = 0.51 |

| Morita et al., 201073 | Cohort study of 1,023 Japanese workers initially free of MetS components | Adjusted for confounders; those participants with periodontal pockets at baseline (CPI ≥3) had greater odds of obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) 4 years later; OR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.0 to 3.0) |

| Weyent et al., 200498 | Cohort study of 1,053 community adults in the U.S. aged ≥65 years at two study sites | Adjusted for confounders; each 10% increase in baseline extent of sites with PD ≥6 mm associated with 2-year prospective weight loss of ≥5% of baseline body weight; OR: 1.55 (95% CI: 1.36 to 1.78) |

| Ylostalo et al., 2008103 | Cross-sectional study of 2,810 community adults without diabetes aged 30 to 49 years in Finland | Adjusted for confounders; the number of teeth with PD ≥6 mm among the highest BMI quintile (>29.1 kg/m) was 1.0 times the number in the lowest BMI quintile; 95% CI: 0.7 to 1.6; crude ratio: 1.7 (1.0 to 2.7); Poisson regression with total number of teeth as offset |

PD = probing depth; CPI = Community Periodontal Index.

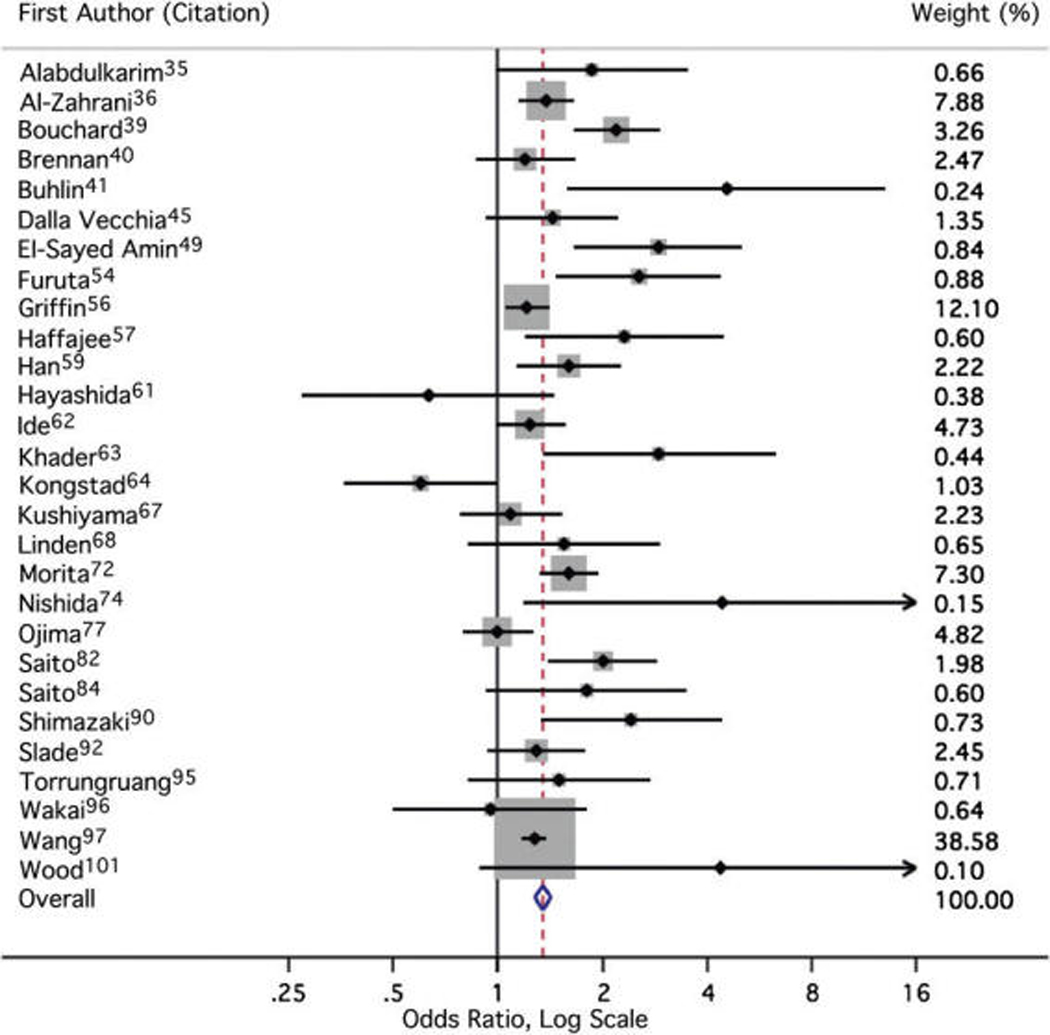

For the association between prevalent periodontal disease and obesity, the overall fixed-effects sOR and Shore-corrected 95% CI was 1.35 (1.23 to 1.47) with a χ2 statistic for heterogeneity (Q) of 81.7 with 27 degrees of freedom (P <0.005) (Fig. 2). The DerSimonian-Laird random effects sOR was 1.48 (95% CI: 1.32 to 1.66). One study97 accounted for 39% of the weight assigned in calculating the sOR; however, the exclusion of this result raised the overall estimate only slightly to 1.40 (Shore-corrected 95% CI: 1.25 to 1.57). The exclusion of no other individual result altered the sOR by >0.02 units in either direction.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis forest plot. The forest plot is a graphical depiction of the individual results that contributed to meta-analysis. Sizes of the boxes are proportional to the weight assigned to each result in calculating the fixed-effects sOR, where weight was assigned inversely to precision.

Combining those results37,41,42,46,50–52,57,60,65,66, 69,70,72,76,78–80,84,85,90,94,98,99,101,102 in Table 2 generated an sMD of 0.80 BMI units (95% CI: 0.70 to 0.95) comparing individuals with periodontal disease to those without periodontal disease (Q = 135.4; P <0.005). The studies43,47,63,64,86 that compared clinical AL across obese and non-obese groups (Table 3) yielded an sMD of 0.58 mm (95% CI: 0.40 to 0.74 mm) with greater clinical AL seen among obese individuals (Q = 5.1; P = 0.40). Eight studies37–39,48, 52,71,90,102 expressed a linear change in the odds of periodontitis with each 1-unit increase in BMI (Table 4), resulting in a summary linear association ratio of 1.02 (Shore-corrected 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.04) and a Q statistic of 12.7 (P= 0.08).

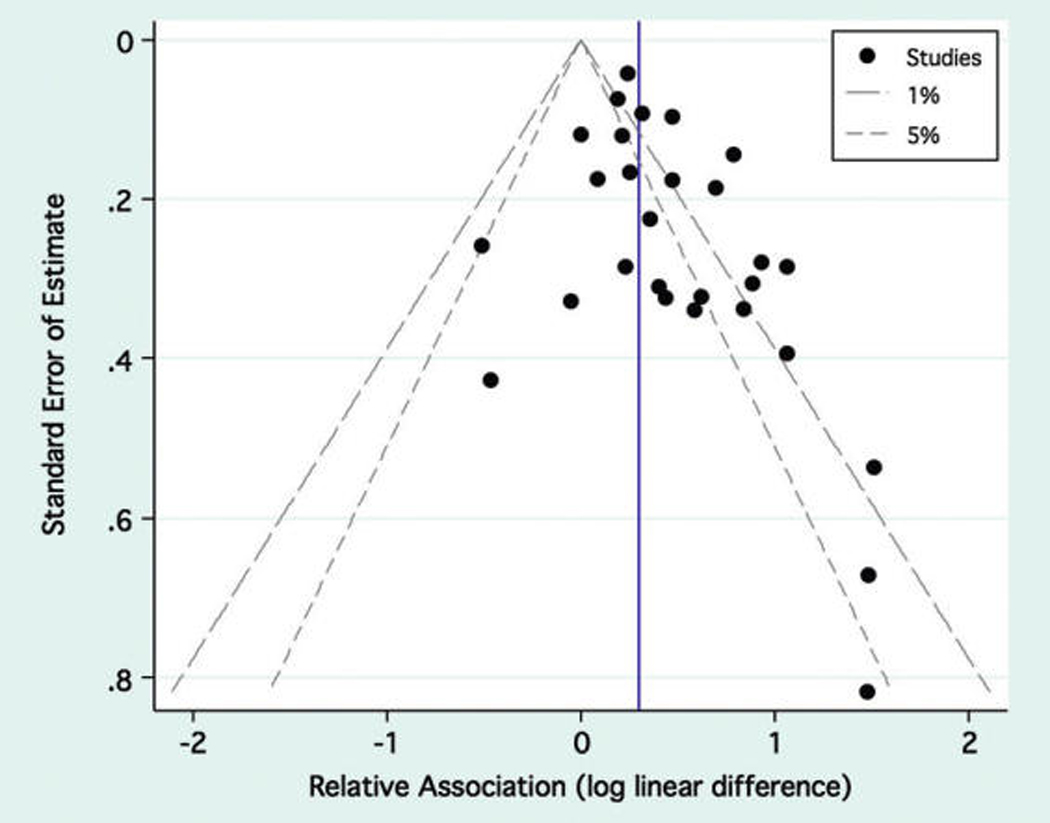

Figure 3 displays the precision of the results from Table 1 as a function of the strength of association. The three largest estimates of a positive obesity–periodontitis association were also the three least precise estimates abstracted.41,74,101 The Begg test suggested a trend of increasingly positive association measures with decreasing precision (continuity corrected P = 0.08). The trim-and-fill procedure estimated the sOR if analogous low-precision measures of an inverse association had theoretically been present. This procedure added seven hypothetical study results but only slightly lowered the sOR to 1.32 (Shore-corrected 95% CI: 1.20 to 1.44).

Figure 3.

Precision versus strength funnel plot. The funnel plot depicts the study precision as a function of the strength of association. The outer borders of the funnel represent the required strength of association to obtain statistical significance at any given level of precision for a critical α for hypothesis tests of 1% or 5%. The vertical blue line represents the sOR for combining all 28 studies.

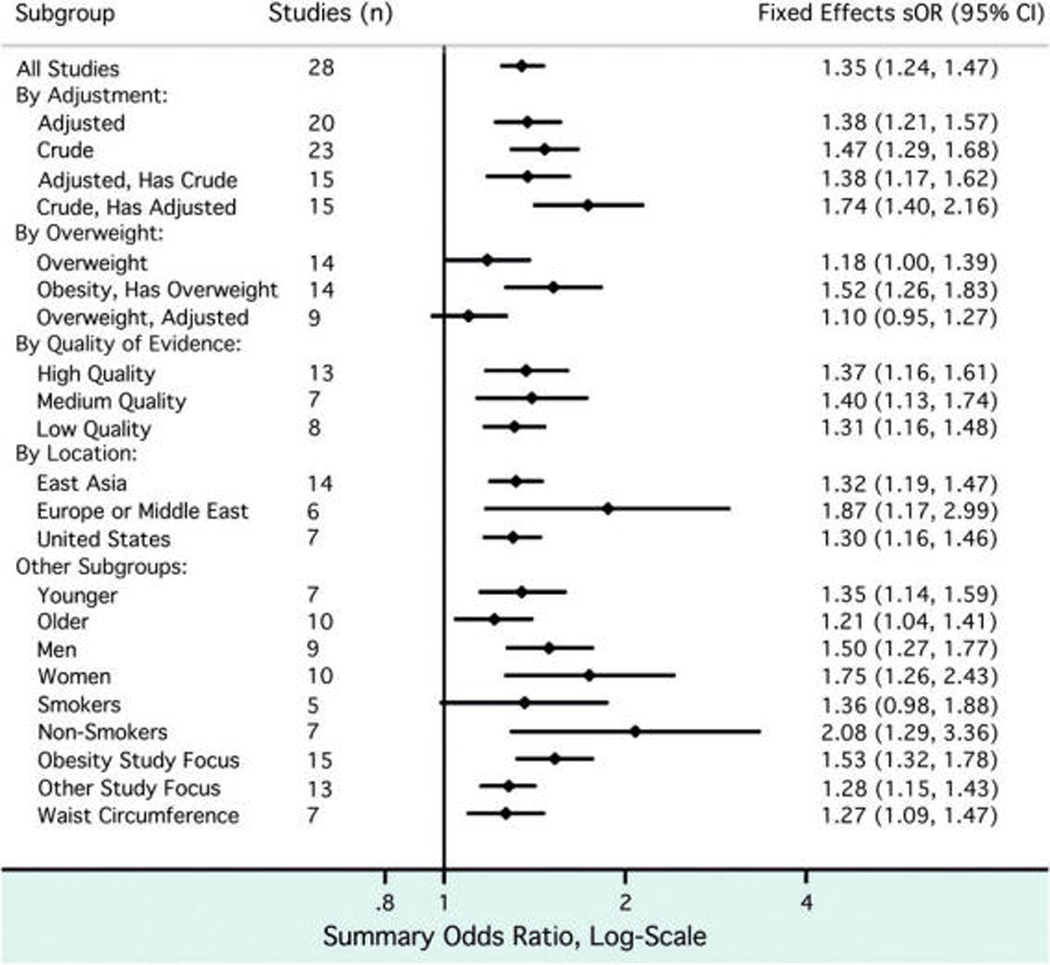

The results shown in Table 1 were divided into groups based on study characteristics, and fixed-effects sORs were recalculated by group (Fig. 4). If a particular study presented stratified results, for example among men and women, the appropriate stratum-specific result was abstracted for subgroup analyses. Among the 15 studies35,36,45,54,57,63,64,67,68,72,74,77, 84,90,96 that presented both crude and adjusted estimates, the pooled adjusted measure was lower. Similarly, a less-positive association was seen with overweight than with obesity among 14 studies36,39,45,49,57,59,63,64,68,74,92,95, 96,101 that provided both estimates. There appeared to be a stronger association between periodontal disease and obesity when results were only based on younger individuals, women, and non-smokers, as well as when a study specifically aimed to estimate an association between periodontal disease and obesity or MetS as a primary objective. No obvious pattern emerged by the quality-of-evidence levels. Summary estimates were similar whether BMI or waist circumference was used to define obesity based on the results of eight studies drawing from seven independent populations.36,49,59,63,84,89,95,97

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of studies included in meta-analysis. The study results contributing to the meta-analysis were divided into groups based on study characteristics (left), and fixed-effects sORs were calculated accordingly.

DISCUSSION

A positive association was repeatedly demonstrated between prevalent periodontal disease and obesity across multiple studies from around the world. The meta-analysis of the systematically identified results from 57 independent study populations suggested an approximate one-third increase in the prevalence odds of obesity among subjects with periodontal disease, a greater mean clinical AL among obese individuals, a higher BMI among subjects with periodontal disease, and a slight but not statistically significant linear increase in the odds of periodontal disease with increasing BMI. In total, these findings are highly unlikely due to chance and persist over studies using a multitude of measurement strategies for assessing these two health conditions.

The summary measure of association (sOR) reported here was less strong in magnitude than those reported between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes106 or cardiovascular events.107 However, based on a subset of included studies, there appears to be stronger obesity–periodontitis association in women, non-smokers, and younger individuals than in the general adult population. Although smoking is a well-studied predisposing factor for periodontitis,108,109 smoking and BMI share a complex relationship,110 which can appear to be inverse in certain populations.111,112 For older individuals, tooth loss and impaired masticatory function might be a path through which advanced periodontal disease could impact energy balance and nutrition.113 Studies that linked overweight or obesity to tooth loss reported positive,114–116 negative,117 and equivocal results118,119 and are complicated by an association between tooth loss and underweight status.113

Though widespread, the use of meta-analysis has been controversial,120–122 and any result must be interpreted cautiously. Confounding and heterogeneity more often influence observational studies than clinical trials, which is a limitation in pooling results. Although oral diseases are sometimes presented as if separate entities from systemic conditions, shared risk factors, such as behavior and genetic predisposition, frequently precede the manifestation of disease. Incomplete accounting of confounding factors has made drawing unequivocal conclusions about periodontal-systemic disease connections an elusive goal.123–125 Neither the sMD reflecting pooled differences in clinical AL across obese and non-obese groups nor the sMD based on pooled differences in BMI across periodontal disease patients and healthy controls was adjusted to account for confounding and, thus, likely overstates any causal difference across groups. However, the sOR based solely on adjusted results did not differ greatly from that comprised of all studies and maintained a statistically significant positive association (Fig. 4). However, for studies that presented both adjusted and crude results, the adjusted sOR was lower and remained potentially biased by unmeasured factors such as physical inactivity,37,126 alcohol use,127 and stress.128

The preferential publication of statistically significant positive results, or those deemed important, might theoretically bias the results of any meta-analysis.129,130 Indeed, we observed a handful of results in the literature with low precision but strongly positive findings (Fig. 3). However, attempts to account for small study effects, either by exclusion or trim-and-fill techniques, did not greatly alter the sOR estimate.

The design of nearly all included studies was cross-sectional, making it impossible to determine the temporal relationship between diseased states. Whether one condition stands as a risk factor for another, or whether a measured covariable might represent a confounder or mediator on a causal pathway, could not be distinguished. Recent work73 showed that individuals with periodontal pockets at baseline were more likely to develop components of MetS, including obesity, 4 years later. Two other prospective studies131,132 appeared during the literature search but were excluded because of a lack of peer review. Hopefully, these efforts preclude the arrival of more high-quality prospective studies that are necessary to validate the proposed causal links between obesity and periodontitis.

To our knowledge, the present analysis is the first on this topic that was systematic and quantitative in approach. We estimated the magnitude of the periodontal disease–obesity association with weighting by study precision and explored differences across subgroups of similar studies. A systematic search allowed for the inclusion of studies for which the association between obesity and periodontal disease was not a primary focus but from which an effect estimate could be abstracted and greatly widened the evidence base for this review.

This review did not cover investigations into the putative causal mechanisms that underlie the observed association between periodontal disease and obesity. However, Bullon et al.15 proposed a bidirectional relationship between MetS and periodontitis mediated by circulating cytokines and oxidative stress. Alternately, Hujoel et al.133 argued that a failure to account for correlations among health-promoting behaviors could create strong but spurious associations between oral factors and systemic conditions, such as seen between obesity and a lack of flossing. Although the cross-sectional association between obesity and periodontal disease is consistent with a causal framework, deciphering the directionality of this relationship cannot be accomplished based on prevalence studies alone.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the prospects of unmeasured confounding, a positive association between periodontal disease and obesity was suggested across diverse populations. Elucidating any physiologic mechanism behind this relationship will require well-designed prospective studies. For the clinician, continuing to stress the importance of maintaining a healthy weight, as recommended by the National Institutes of Health,134 stands to benefit all patients. The prevalence of periodontal disease is likely to be higher among obese patients, although there is no current evidence to recommend differences in treatment planning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs.AllanSmith, Department of Environmental Health Sciences, and Craig Steinmaus, Division of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, for comments on the manuscript and for recommendations regarding statistical methods. Dr. Chaffee is supported by a dental scientist training grant (DE007306) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland.

Footnotes

Stata IC version 10.1, StataCorp, College Station, TX.

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894(i–xii):1–253. [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2003;916(i–viii):1–149. backcover. [PubMed]

- 3.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal disease: Current concepts. J Periodontol. 1992;63 Suppl. 4:322–331. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh PD. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8:263–271. doi: 10.1177/08959374940080022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–1820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol. 2003;8:38–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: An update on the associations and risk. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35 Suppl. 8:362–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mealey BL, Oates TW. American Academy of Periodontology. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1289–1303. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khader YS, Ta’ani Q. Periodontal diseases and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: A meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2005;76:161–165. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weidlich P, Cimões R, Pannuti CM, Oppermann RV. Association between periodontal diseases and systemic diseases. Braz Oral Res. 2008;22 Suppl. 1:32–43. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242008000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams RC, Barnett AH, Claffey N, et al. The potential impact of periodontal disease on general health: A consensus view. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1635–1643. doi: 10.1185/03007990802131215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perlstein MI, Bissada NF. Influence of obesity and hypertension on the severity of periodontitis in rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43:707–719. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezera BB, Sallum EA, Sallum AW. Obesity and periodontal disease: Why suggest such relationship? An overview. Braz J Oral Sci. 2007;6:1420–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boesing F, Patiño JS, da Silva VR, Moreira EA. The interface between obesity and periodontitis with emphasis on oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Obes Rev. 2009;10:290–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bullon P, Morillo JM, Ramirez-Tortosa MC, Quiles JL, Newman HN, Battino M. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: Is oxidative stress a common link? J Dent Res. 2009;88:503–518. doi: 10.1177/0022034509337479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cullinan MP, Ford PJ, Seymour GJ. Periodontal disease and systemic health: Current status. Aust Dent J. 2009;54 Suppl. 1:S62–S69. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pischon N, Heng N, Bernimoulin JP, Kleber BM, Willich SN, Pischon T. Obesity, inflammation, and periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2007;86:400–409. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie CS. Obesity and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44:154–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2007.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito T, Shimazaki Y. Metabolic disorders related to obesity and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2007;43:254–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stabholz A, Soskolne WA, Shapira L. Genetic and environmental risk factors for chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:138–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collin HL, Sorsa T, Meurman JH, et al. Salivary matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-8) levels and gelatinase (MMP-9) activities in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Periodontal Res. 2000;35:259–265. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2000.035005259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt AM, Weidman E, Lalla E, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) induce oxidant stress in the gingiva: A potential mechanism underlying accelerated periodontal disease associated with diabetes. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:508–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonoki K, Nakashima S, Takata Y, et al. Decreased lipid peroxidation following periodontal therapy in type 2 diabetic patients. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1907–1913. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapple IL, Brock GR, Milward MR, Ling N, Matthews JB. Compromised GCF total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis: Cause or effect? J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:103–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karthikeyan BV, Pradeep AR. Gingival crevicular fluid and serum leptin: Their relationship to periodontal health and disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petitti D. Meta-Analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost Effectiveness Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shore RE, Gardner MJ, Pannett B. Ethylene oxide: An assessment of the epidemiological evidence on carcinogenicity. Br J Ind Med. 1993;50:971–997. doi: 10.1136/oem.50.11.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petitti D. Meta-Analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost Effectiveness Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Light R, Pillemer D. Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1984. pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alabdulkarim M, Bissada N, Al-Zahrani M, Ficara A, Siegel B. Alveolar bone loss in obese subjects. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2005;7:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle-aged, and older adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:610–615. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Zahrani MS, Borawski EA, Bissada NF. Increased physical activity reduces prevalence of periodontitis. J Dent. 2005;33:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borges-Yáñez SA, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Maupomé G. Risk factors and prevalence of periodontitis in community-dwelling elders in Mexico. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouchard P, Boutouyrie P, Mattout C, Bourgeois D. Risk assessment for severe clinical attachment loss in an adult population. J Periodontol. 2006;77:479–489. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brennan RM, Genco RJ, Wilding GE, Hovey KM, Trevisan M, Wactawski-Wende J. Bacterial species in subgingival plaque and oral bone loss in postmenopausal women. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1051–1061. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Pockley AG, Frostegård J, Klinge B. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with periodontitis. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:2099–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buhlin K, Hultin M, Norderyd O, et al. Risk factors for atherosclerosis in cases with severe periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:541–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapper A, Munch A, Schermann C, Piacentini CC, Fasolo MT. Obesity and periodontal disease in diabetic pregnant women. Braz Oral Res. 2005;19:83–87. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242005000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Aiuto F, Sabbah W, Netuveli G, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with severe periodontitis in a large U.S. population-based survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3989–3994. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalla Vecchia CF, Susin C, Rösing CK, Oppermann RV, Albandar JM. Overweight and obesity as risk indicators for periodontitis in adults. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1721–1728. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dietrich T, Kaye EK, Nunn ME, Van Dyke T, Garcia RI. Gingivitis susceptibility and its relation to periodontitis in men. J Dent Res. 2006;85:1134–1137. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dumitrescu AL, Kawamura M. Involvement of psychosocial factors in the association of obesity with periodontitis. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:115–124. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ekuni D, Yamamoto T, Koyama R, Tsuneishi M, Naito K, Tobe K. Relationship between body mass index and periodontitis in young Japanese adults. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:417–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El-Sayed Amin H. Relationship between overall and abdominal obesity and periodontal disease among young adults. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franek E, Klamczynska E, Ganowicz E, Blach A, Budlewski T, Gorska R. Association of chronic periodontitis with left ventricular mass and central blood pressure in treated patients with essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:203–207. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furugen R, Hayashida H, Yamaguchi N, et al. The relationship between periodontal condition and serum levels of resistin and adiponectin in elderly Japanese. J Periodontal Res. 2008;43:556–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furuichi Y, Shimotsu A, Ito H, et al. Associations of periodontal status with general health conditions and serum antibody titers for Porphyromonas gingivalis and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1491–1497. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.10.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Furukawa T, Wakai K, Yamanouchi K, et al. Associations of periodontal damage and tooth loss with atherogenic factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Intern Med. 2007;46:1359–1364. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furuta M, Ekuni D, Yamamoto T, et al. Relationship between periodontitis and hepatic abnormalities in young adults. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:27–33. doi: 10.3109/00016350903291913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodontol. 2005;76 Suppl. 11:2075–2084. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffin SO, Barker LK, Griffin PM, Cleveland JL, Kohn W. Oral health needs among adults in the United States with chronic diseases. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1266–1274. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Relation of body mass index, periodontitis and Tannerella forsythia. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han DH, Lim SY, Sun BC, et al. Mercury exposure and periodontitis among a Korean population: The Shiwha-Banwol environmental health study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1928–1936. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han DH, Lim SY, Sun BC, Paek DM, Kim HD. Visceral fat area-defined obesity and periodontitis among Koreans. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hattatoglu-Sönmez E, Ozcakar L, Gökce-Kutsal Y, Karaagaoglu E, Demiralp B, Nazliel-Erverdi H. No alteration in bone mineral density in patients with periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2008;87:79–83. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hayashida H, Kawasaki K, Yoshimura A, et al. Relationship between periodontal status and HbA1c in nondiabetics. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:204–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ide R, Hoshuyama T, Takahashi K. The effect of periodontal disease on medical and dental costs in a middle-aged Japanese population: A longitudinal worksite study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2120–2126. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.070193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khader YS, Bawadi HA, Haroun TF, Alomari M, Tayyem RF. The association between periodontal disease and obesity among adults in Jordan. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kongstad J, Hvidtfeldt UA, Grønbaek M, Stoltze K, Holmstrup P. The relationship between body mass index and periodontitis in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1246–1253. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kshirsagar AV, Craig RG, Beck JD, et al. Severe periodontitis is associated with low serum albumin among patients on maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:239–244. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02420706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar S, Dagli RJ, Dhanni C, Duraiswamy P. Relationship of body mass index with periodontal health status of green marble mine laborers in Kesariyaji, India. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23:365–369. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kushiyama M, Shimazaki Y, Yamashita Y. Relationship between metabolic syndrome and periodontal disease in Japanese adults. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1610–1615. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Linden G, Patterson C, Evans A, Kee F. Obesity and periodontitis in 60–70-year-old men. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, Van der Velden U. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1528–1534. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Machado AC, Quirino MR, Nascimento LF. Relation between chronic periodontal disease and plasmatic levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol and fractions. Braz Oral Res. 2005;19:284–289. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242005000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marugame T, Hayasaki H, Lee K, Eguchi H, Matsumoto S. Alveolar bone loss associated with glucose tolerance in Japanese men. Diabet Med. 2003;20:746–751. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morita T, Ogawa Y, Takada K, et al. Association between periodontal disease and metabolic syndrome. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:248–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morita T, Yamazaki Y, Mita A, et al. A cohort study on the association between periodontal disease and the development of metabolic syndrome. J Periodontol. 2010;81:512–519. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nishida N, Tanaka M, Hayashi N, et al. Determination of smoking and obesity as periodontitis risks using the classification and regression tree method. J Periodontol. 2005;76:923–928. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nishimura F, Kono T, Fujimoto C, Iwamoto Y, Murayama Y. Negative effects of chronic inflammatory periodontal disease on diabetes mellitus. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2000;2:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Noack B, Genco RJ, Trevisan M, Grossi S, Zambon JJ, De Nardin E. Periodontal infections contribute to elevated systemic C-reactive protein level. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1221–1227. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojima M, Hanioka T, Tanaka K, Inoshita E, Aoyama H. Relationship between smoking status and periodontal conditions: Findings from national databases in Japan. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Phipps KR, Chan BK, Madden TE, et al. Longitudinal study of bone density and periodontal disease in men. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1110–1114. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pitiphat W, Joshipura KJ, Rich-Edwards JW, Williams PL, Douglass CW, Gillman MW. Periodontitis and plasma C-reactive protein during pregnancy. J Periodontol. 2006;77:821–825. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pitiphat W, Savetsilp W, Wara-Aswapati N. C-reactive protein associated with periodontitis in a Thai population. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reeves AF, Rees JM, Schiff M, Hujoel P. Total body weight and waist circumference associated with chronic periodontitis among adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:894–899. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Koga T, Tsuzuki M, Ohshima A. Relationship between upper body obesity and periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1631–1636. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saito T, Murakami M, Shimazaki Y, Oobayashi K, Matsumoto S, Koga T. Association between alveolar bone loss and elevated serum C-reactive protein in Japanese men. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1741–1746. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.12.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Kiyohara Y, et al. Relationship between obesity, glucose tolerance, and periodontal disease in Japanese women: The Hisayama study. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saito T, Yamaguchi N, Shimazaki Y, et al. Serum levels of resistin and adiponectin in women with periodontitis: The Hisayama study. J Dent Res. 2008;87:319–322. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sarlati F, Akhondi N, Ettehad T, Neyestani T, Kamali Z. Relationship between obesity and periodontal status in a sample of young Iranian adults. Int Dent J. 2008;58:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saxlin T, Suominen-Taipale L, Kattainen A, Marniemi J, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P. Association between serum lipid levels and periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:1040–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Saxlin T, Suominen-Taipale L, Leiviskä J, Jula A, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P. Role of serum cytokines tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in the association between body weight and periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:100–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shimazaki Y, Saito T, Yonemoto K, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Yamashita Y. Relationship of metabolic syndrome to periodontal disease in Japanese women: The Hisayama Study. J Dent Res. 2007;86:271–275. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shimazaki Y, Egami Y, Matsubara T, et al. Relationship between obesity and physical fitness and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1124–1131. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Skaleric U, Kovac-Kavcic M. Some risk factors for the progression of periodontal disease. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2000;2:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, Beck JD, Riche E, Offenbacher S. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1172–1179. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:135–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Söder B, Airila Månsson S, Söder PO, Kari K, Meurman J. Levels of matrix metalloproteinases-8 and -9 with simultaneous presence of periodontal pathogens in gingival crevicular fluid as well as matrix metalloproteinase-9 and cholesterol in blood. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:411–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Torrungruang K, Tamsailom S, Rojanasomsith K, et al. Risk indicators of periodontal disease in older Thai adults. J Periodontol. 2005;76:558–565. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wakai K, Kawamura T, Umemura O, et al. Associations of medical status and physical fitness with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:664–672. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.261006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang TT, Chen TH, Wang PE, et al. A population-based study on the association between type 2 diabetes and periodontal disease in 12,123 middle-aged Taiwanese (KCIS No. 21) J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:372–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weyant RJ, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Periodontal disease and weight loss in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:547–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wolff RE, Wolff LF, Michalowicz BS. A pilot study of glycosylated hemoglobin levels in periodontitis cases and healthy controls. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1057–1061. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wood N, Johnson RB, Streckfus CF. Comparison of body composition and periodontal disease using nutritional assessment techniques: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:321–327. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wood N, Johnson RB. The relationship between smoking history, periodontal screening and recording (PSR) codes and overweight/obesity in a Mississippi dental school population. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xiao LM, Yan YX, Xie CJ, et al. Association among interleukin-6 gene polymorphism, diabetes and periodontitis in a Chinese population. Oral Dis. 2009;15:547–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ylöstalo P, Suominen-Taipale L, Reunanen A, Knuuttila M. Association between body weight and periodontal infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yu YH, Kuo HK, Lai YL. The association between serum folate levels and periodontal disease in older adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001/02. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wimmer G, Pihlstrom BL. A critical assessment of adverse pregnancy outcome and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35 Suppl. 8:380–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Blaizot A, Vergnes JN, Nuwwareh S, Amar J, Sixou M. Periodontal diseases and cardiovascular events: Meta-analysis of observational studies. Int Dent J. 2009;59:197–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2000;71:743–751. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tonetti MS. Cigarette smoking and periodontal diseases: Etiology and management of disease. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:88–101. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chiolero A, Faeh D, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:801–809. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Xu F, Yin XM, Wang Y. The association between amount of cigarettes smoked and overweight, central obesity among Chinese adults in Nanjing, China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16:240–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hou X, Jia W, Bao Y, et al. Risk factors for overweight and obesity, and changes in body mass index of Chinese adults in Shanghai. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, Finch S, Walls AW. The relationship between oral health status and body mass index among older people: A national survey of older people in Great Britain. Br Dent J. 2002;192:703–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, de Sousa MdaL, Bozzetti MC. Oral status and its association with obesity in Southern Brazilian older people. Gerodontology. 2009;26:46–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2008.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Marcenes W, Steele JG, Sheiham A, Walls AW. The relationship between dental status, food selection, nutrient intake, nutritional status, and body mass index in older people. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:809–816. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sahyoun NR, Lin CL, Krall E. Nutritional status of the older adult is associated with dentition status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:61–66. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Taguchi A, Sanada M, Suei Y, et al. Tooth loss is associated with an increased risk of hypertension in postmenopausal women. Hypertension. 2004;43:1297–1300. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128335.45571.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.de Andrade FB, de França Caldas AJ, Jr, Kitoko PM. Relationship between oral health, nutrient intake and nutritional status in a sample of Brazilian elderly people. Gerodontology. 2009;26:40–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2008.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ostberg AL, Nyholm M, Gullberg B, Råstam L, Lindblad U. Tooth loss and obesity in a defined Swedish population. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:427–433. doi: 10.1177/1403494808099964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Greenland S. Invited commentary: A critical look at some popular meta-analytic methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:290–296. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Schmid CH. Summing up evidence: One answer is not always enough. Lancet. 1998;351:123–127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shapiro S. Meta-analysis/Shmeta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:771–778. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chong PH, Kezele B. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Confounding effects or epiphenomenon? Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:805–818. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.9.805.35189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, DeRouen TA. Periodontitis-systemic disease associations in the presence of smoking — Causal or coincidental? Periodontol 2000. 2002;30:51–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Spiekerman CF, Hujoel PP, DeRouen TA. Bias induced by self-reported smoking on periodontitis-systemic disease associations. J Dent Res. 2003;82:345–349. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Merchant AT, Pitiphat W, Rimm EB, Joshipura K. Increased physical activity decreases periodontitis risk in men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:891–898. doi: 10.1023/a:1025622815579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pitiphat W, Merchant AT, Rimm EB, Joshipura KJ. Alcohol consumption increases periodontitis risk. J Dent Res. 2003;82:509–513. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM, et al. A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1491–1504. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hopewell S, Loudon K, Clarke MJ, Oxman AD, Dickersin K. Publication bias in clinical trials due to statistical significance or direction of trial results. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):MR000006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000006.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L, et al. Dissemination and publication of research findings: An updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(ii, ix–xi):1–193. doi: 10.3310/hta14080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gaio EJ. Effect of obesity on periodontal attachment loss progression: A 5-years population-based prospective study (in Portuguese). [Thesis] Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2008. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Marsicano JA. Evaluation of the oral health conditions of the obese patients and submitted to the bariatric surgery (in Portuguese). [Thesis] Bauru, SP, Brazil: Universidade de São Paulo; 2008. p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hujoel PP, Cunha-Cruz J, Kressin NR. Spurious associations in oral epidemiological research: The case of dental flossing and obesity. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:520–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults — The evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6 Suppl. 2:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]