Abstract

Theory suggests that relationship inequity will be associated with less marital and personal distress among the more religious, and that this interaction effect will be stronger for women than men. Data are from 178 married couples experiencing the third trimester of pregnancy of their first biological child. Five outcome variables were assessed for each spouse: marital satisfaction, love, marital conflict, depression, and anxiety. Consistent with equity theory, perceived relative advantage was related in a non-monotonic fashion to all outcomes, with increasing advantage predicting better outcomes up to the equity point, but worse outcomes afterwards. Sanctification of marriage appeared to be a more important moderator of inequity effects than general religiousness. In particular, relative advantage had weaker effects among higher sanctifiers. The influence of relative advantage was also conditioned by gender. Wives’ psychological well-being appeared to be more adversely affected than men’s due to considering oneself overbenefited in the relationship. Moreover, the interaction between sanctification and relative advantage was somewhat stronger for wives.

Keywords: equity theory, marital satisfaction, love, depression, religiousness, sanctification

Equity theory suggests that people are distressed by distributive injustice in relations with others. There is considerable support for this principle in employer-employee relations and other relationships centered on bargaining for advantage (Adams, 1965; Hatfield, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978). However, scholars are in disagreement regarding its applicability to marriage. Some maintain that happily partnered couples are either unaware of, or indifferent to, equity issues (Holmes & Levinger, 1994; Smith, Gager, & Morgan, 1998), or that, if anything, it is relationship distress that precipitates accusations of injustice (Grote & Clark, 2001). Some research supports these positions, finding either little or no influence of inequity on marital outcomes (e.g., Gager & Sanchez, 2003), or that marital distress precedes the perception of inequity (Grote & Clark). Others, in contrast, maintain that couples remain continually aware of the exchange balance in their relationship, regardless of their marital satisfaction, and that inequity leads to both dissatisfaction and divorce (DeMaris, 2007; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Joyner, in press). To date, then, the extent to which equity considerations precipitate distress in marriage is still an unsettled question (see also Hatfield, Rapson, & Aumer-Ryan, 2008).

A second issue is the extent to which any distress prompted by inequity might be buffered or exacerbated by other factors. For example, gender has been found to play an important role. Several studies have found women to be more sensitive than men to inequitable exchanges in romantic relationships. Women are not only more likely to report being underbenefited (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990), but their relationship satisfaction also appears to respond more negatively than men’s to such injustice (Grote & Clark, 2001; Sprecher, 2001). Additional work has found that inequity is less distressing among those who are low in exchange orientation (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991), or when one spouse is impaired by illness (Kuijer, Buunk, & Ybema, 2001). However, to date, relatively little attention has been paid to the role of religiousness as a possible buffer of the effect of inequity. This is surprising in light of the pervasive influence of religion on American life, particularly marriage. The majority of American married adults report having a religious affiliation and attending church with some regularity (Mahoney, Pargament, Tarakeshwar, & Swank, 2001). Moreover, Judeo-Christian theologies tend to downplay the importance of personal gratification in marriage. Instead, emphasis is placed on responding to the needs of one’s spouse (Mahoney, 2005; Murray-Swank, Mahoney, & Pargament, 2005; Wilcox, 2004; Wilcox & Nock, 2006). It is therefore expected that imbalanced marital exchanges would be less linked to distress among more religious individuals, particularly those who view the marriage itself as having spiritual meaning and purpose.

In the current study, we address these issues in an ideal “laboratory.” We utilize a sample of married couples expecting their first biological child to re-examine the relationship between inequitable exchange and several indices of psychological distress. The event of an impending first birth is a particularly happy period in marriage (Lawrence, Cobb, Rothman, Rothman, & Bradbury, 2008; Snowden, Schott, Awalt, & Gillis-Knox, 1988), and one in which concerns with tit-for-tat exchange should be at a minimum. Should distributive injustice be associated with distress in this instance, the case for the importance of equity considerations in marriage is strengthened. We also examine whether inequity is less related to distress among the more religious, using well-established atheoretical markers of general religiousness (i.e., church attendance, prayer) and a more recently researched but conceptually rich construct that taps into the spiritual meaning of marriage (i.e., sanctification of marriage; see, e.g., Mahoney, Pargament, Murray-Swank, & Murray-Swank, 2003). We expect both indices to have a buffering effect, although the latter to be a relatively more powerful moderator. And we re-assess the extent to which gender conditions these associations.

Theoretical Considerations

Equity Theory and its Applicability to Marriage

Equity theorists argue that people are distressed by relationships that are characterized by an imbalanced exchange (Adams, 1965; Hatfield, et al., 1978; Sprecher, 1986). This occurs whenever one’s rewards from the relationship are incommensurate with one’s contributions to it. Additionally, the theory suggests that people are uncomfortable whether unduly profiting from the exchange or being exploited by it. However, underbenefit is held to be more damaging to well-being than overbenefit. The overbenefited are, at the least, the ones who are in fact profiting from the exchange. And not only is overbenefit an ego-enhancing experience, but it is also easier to effect a restoration of equity from such a privileged position. One need only accept less from, or give more to, the partner to redress the imbalance (Longmore & DeMaris, 1997). Overall, people are most comfortable with relationships that are equitable to both participants.

Equity theory has received considerable support when applied to employer-employee relationships or fleeting associations among relative strangers (see Adams, 1965; Hatfield, et al., 1978, for reviews of the experimental evidence). However, a preoccupation with getting adequate return on one’s “investment” is held by many to be inapplicable to long-term romantic relationships (Holmes & Levinger, 1994), especially happy ones (Smith, Gager, & Morgan, 1998). Wilcox and Nock (2006, p. 1324) argue that marital exchange follows an “enchanted cultural logic of gift exchange.” Spouses’ contributions to the marriage and to each other constitute gifts of both instrumental and symbolic value for which there is often no expectation of reciprocation. Consistent with this, several studies find either little or no influence of equity considerations on the quality or longevity of marriages and other intimate unions (Felmlee, Sprecher, & Bassin, 1990; Gager & Sanchez, 2003; Lujansky & Mikula, 1983; Sprecher, 2001). Grote and Clark (2001) even suggest that, if anything, perceptions of injustice are the product, rather than the cause, of distress. They maintain that intimate couples do not normally keep track of each person’s relative contributions to the relationship until they are dissatisfied with it. At this juncture, a search for causes of the distress often “uncovers” inequities that had heretofore gone unnoticed. Once accusations of injustice are traded in open conflict, they precipitate further distress, in turn. Using three waves of data from couples, the authors marshal evidence for a sequence in which distress at time 1 leads to a perception of underbenefit at time 2, which then leads to further distress at time 3.

In contrast, several scholars argue that equity is an ever-present consideration in marriage, as well as other romantic relationships (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; DeMaris, 2007; Hatfield et al., 1978; Hatfield, et al., 2008). This is partially due to an increasingly deinstitutionalized marital institution with little remaining authority to mandate the continuance of the conjugal bond (Cherlin, 2004). Instead, marriage is thought to be viewed in a positive light to the extent that it continues to provide personal gratification and individual growth (Amato, 2004). Individuals are therefore expected to treat romantic relationships as “investments” that need continual monitoring to assess whether they are worth their “costs.” Consistent with this, several studies have found inequity, especially of the underbenefiting kind, to be a harbinger of emotional distress, relationship dissatisfaction, or even union disruption (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; DeMaris, 2007, 2008; DeMaris & Longmore, 1996; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Joyner, in press; Lennon and Rosenfield, 1994; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). Nonetheless, the question remains whether relationship inequity is associated with distress in otherwise happy marriages.

Sanctification of Marriage and General Religiousness as a Buffer

The institution of marriage holds special status across world religions and believers are encouraged to view their marriage as sanctified (Mahoney et al., 2003). As defined by Mahoney and her colleagues, sanctification is a psychospiritual construct that refers to viewing an aspect of life as having divine character and significance (Mahoney et al.; Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Mahoney et al. (1999) found that those who perceived their marriages as sacred reported greater personal benefits from marriage and less marital conflict. And when conflict did arise, high sanctifiers reported greater use of collaborative, as opposed to destructive, forms of communication. Moreover, according to emerging theory and research related to sanctification, those who view their marriage as a sacred bond are obliged to do whatever necessary to protect the relationship, including sacrificing their own wants unselfishly and focusing instead on their spouse’s needs (Mahoney et al., 2003; Pargament & Mahoney, 2005; Wilcox, 2004). Further, when viewed through a sacred lens, marriage represents a transcendent pathway that cannot be earned solely through human efforts but can offer unmerited benefits that should be accepted with spiritual emotions, such as joy and gratitude. One would therefore expect inequity to have a weaker effect on marital quality among those who view their marriage as highly sanctified. This could either be due to equity concerns being less paramount for this group, or to inequity being less likely to be noticed by them. Moreover, this moderating effect of sanctification is likely to be more robust than what would be detected using more distal indicators of religiousness, such as church attendance or frequency of prayer, that do not directly assess people’s religiously based views of the marriage itself (Mahoney et al., 1999). Nevertheless, to date, little work has examined how the sanctification of marriage or general markers of religiousness might interact with inequity in their effects on marital quality. Hansen (1987), however, found exchange constructs such as equity, equality, and reward level to be better predictors of marital adjustment for females low, as opposed to high, on religiosity. And DeMaris (2008) found that the positive link between being objectively underbenefited, with respect to contributions to income, paid labor, housework, and health, and the perception of being underbenefited was significantly weaker among the more, rather than the less, religious.

The Influence of Gender

Men and women are not equally affected by distributive injustice in romantic relationships. Women tend to perceive themselves as more underbenefited and less overbenefited in relationships, compared to men (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). They are also more disturbed by being underbenefited than men (DeMaris, 2007, 2008; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Sprecher, 1992). At the same time, Sprecher (1992) found women to expect to feel more guilt than men in response to being overbenefited. There are several reasons for such gender differences. Women are seen as being more objectively disadvantaged in relationships than men, due to lingering gender differences in power and status (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; Grote & Clark, 2001; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). Women’s greater relationship focus (Sprecher, 2001) may also render them more sensitive to injustices and more likely to react negatively to being exploited. And an increased emphasis on gender equality in modern marriage may lead women to be more vigilant about, and reactive to, relationship injustice (Wilcox & Nock, 2006; Vangelisti & Daly, 1997). Women, as a group, are also more religious than men (Miller & Stark, 2002). Their greater sensitivity to inequity, combined with a stronger connectedness to religious institutions may therefore render them more susceptible to religious messages emphasizing marital sacrifice. That is, the tendency for religiousness to buffer the influence of inequity on distress should be more pronounced for women than men.

Hypotheses

In light of the foregoing, we tender the following hypotheses with respect to the perception of inequity in marriage:

H1: The perception of being either underbenefited or overbenefited is associated with lower marital quality and psychological well being, compared to the perception of being equitably treated.

H2: Underbenefit has a stronger adverse effect on marital quality and psychological well being than overbenefit.

H3: Inequity of either kind has a stronger adverse effect on marital quality and psychological well being for the less, as opposed to the more, religious—whether indexed by general religiousness or sanctification.

H4: Sanctification is a stronger buffer than general religiousness for the effects of inequity.

H5: Inequity of either kind has a stronger adverse effect on marital quality and psychological well being for women than for men.

H6: The buffering effect of religiousness will be stronger for women than for men.

Methods

The Data

The sample consisted of 178 married couples experiencing the third trimester of pregnancy of both spouse’s first biological child. They were drawn from a mid-sized, Midwestern city and surrounding suburban and rural communities. Couples were primarily recruited from childbirth classes, with the rest responding to announcements posted in medical offices, retail locations or newspapers; word of mouth referrals; or direct mail. Both partners were White in 142, or 80% of couples, whereas one or both were minorities in the other 36 or 20% of couples. Average ages were 27.2 for wives and 28.7 for husbands. Inclusionary criteria were that spouses: 1) were married, 2) pregnant with each individual’s first biological child; and 3) both spoke English. In addition, given the focus of the project, it was initially deemed important to insure that at least one of the spouses considered him- or herself at least “slightly religious” or “slightly spiritual.” However, all couples interested in participating in the study met this criterion; hence no one was excluded because of it. Data were collected in couples’ homes. Each spouse independently completed surveys that assessed the constructs used in the study. A research assistant was present throughout, both to answer any questions and to insure that spouses completed the surveys independently. Couples received $75 compensation for participating in one visit made to their home to collect data. Despite the nonprobabilistic sampling scheme, wives in the sample were no more religiously engaged than a comparable national sample of married women drawn from the National Survey of Family Growth (Mahoney, Pargament, & DeMaris, in press).

Outcome Variables

Five response variables are utilized. Marital satisfaction was measured with the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Index (Schumm et al., 1986). This is a three-item scale assessing the degree of satisfaction with (a) the marriage, (b) the spouse, and (c) the relationship with the spouse. Responses to each item ranged from “extremely dissatisfied” (1) to “extremely satisfied” (7). Alpha reliability was .90 for both husbands and wives. Love was tapped with the love subscale from Braiker and Kelley (1979). This is a ten-item scale with representative item “to what extent do you love your spouse at this stage?” Responses to each item ranged from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (9). Alpha reliability was .77 for wives and .81 for husbands. Marital conflict was assessed with the two-item subscale from Kerig’s (1996) Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales. It queries the frequency of (a) minor and (b) major disagreements in the marriage. Responses ranged from “once a year or less” (1) to “just about every day” (6). Alpha reliability was .79 for wives and .80 for husbands. Depression was measured with a 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977). The items ask about the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced in the past week. A representative symptom was “I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me.” Responses ranged from “rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]” (0) to “all of the time [5–7 days]” (3). Alpha reliability was .75 for wives and .74 for husbands. Anxiety was tapped with the 10-item anxiety scale from the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (Veijola et al., 2003). The items tap the frequency of anxiety symptoms in the past week. A representative symptom was “suddenly scared for no reason.” Responses ranged from “not at all” (0) to “extremely” (3). Alpha reliability was .84 for wives and .79 for husbands.

Explanatory Variables

The focal explanatory variable was a five-item scale measuring the perceived equitableness of the marriage. Three of the items were from the National Survey of Families and Households (Sweet, Bumpass, & Call, 1988), and asked how the respondent felt about the fairness in the relationship of (a) household chores, (b) working for pay, and (c) spending money. Responses ranged from “very unfair to me” (1) to “very unfair to him/her” (5). The fourth item was the Hatfield Global Equity Measure (Hatfield, Utne, & Traupmann, 1978), which asked “Considering what both you and your spouse put into the relationship, and what both of you get out of it, how does your relationship ‘stack up’?” Responses range from “my partner is getting a much better deal than I” (1) to “I am getting a much better deal than my partner” (7). The fifth item was Sprecher’s (1986) equity measure: “Sometimes things get out of balance in a relationship and one partner contributes more to the relationship than the other. Consider all the times when the exchange in your relationship has become unbalanced and one partner contributed more than the other for a time. When your relationship becomes unbalanced, which of you is more likely to be the one who contributes more?” Responses ranged from “I am much more likely to be the one to contribute more” (1) to “my partner is much more likely to be the one to contribute more” (7). Because the five items were in different metrics they were standardized first and then summed to create a scale of perceived relative advantage or, relative advantage, for short. Positive scores on the resulting scale reflect overbenefit, whereas negative scores reflect underbenefit. A score of zero reflects the perception of equity, or “parity.” Alpha reliability was .54 for wives and .62 for husbands. Internal consistency was reduced by the nature of the first three items, as would be expected under equity principles. That is, being underbenefited in, say, doing housework, shouldn’t be strongly correlated with being underbenefited in working for pay or spending money, since couples tend to make offsetting contributions in order to keep the relationship equitable (DeMaris, 2007; DeMaris & Longmore, 1996). The correlation between the Hatfield and Sprecher items, on the other hand, is .55 for women and .47 for men.

Sanctification of marriage was measured in two ways. The theistic sanctification of marriage scale was a ten-item scale with representative item “I sense God’s presence in this marriage.” The nontheistic sanctification of marriage scale was also a ten-item scale with representative item “Being with my spouse feels like a deeply spiritual experience.” Responses to items for each scale ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Alpha reliability for the theistic sanctification scale was .98 for both wives and husbands. Alpha reliability for the nontheistic sanctification scale was .93 for wives and .92 for husbands. The general religiousness scale was based on two items measuring the typical frequency of (a) church attendance and (b) prayer. Responses to each question ranged from “never” (1) to “several times a week” (8). Alpha reliability was .79 for wives and .73 for husbands. All religiousness scales are centered, i.e., deviated from their means, in the analyses.

All models controlled for husband’s and wife’s age, the number of years married, and household income in thousands of dollars. Further, it was important to isolate the influence of individuals’ perceptions of injustice over and above their actual inputs and outcomes in the marriage. Therefore the objective exchange balance in the marriage was also held constant via a set of logged ratios tapping wives’ and husbands’ relative contributions to the marriage in the spheres of educational attainment, paid work, housework, and childbirth preparation. Each ratio was of the form: husband’s contribution/wife’s contribution. Logged contribution ratios have been used in previous studies to tap relative objective contributions in marriage (DeMaris, 2007; DeMaris & Longmore, 1996). Educational attainment ranged from “less than 7 years” (1) to “graduate/professional degree” (7). Paid labor was measured as the number of hours per week the respondent “usually works.” Housework hours were assessed by asking respondents to indicate the number of hours per week they normally spent doing nine separate tasks, such as “preparing meals,” or “cleaning house.” Childbirth preparation time was measured by asking how many hours in the past seven days the respondent spent doing various preparatory activities, such as “made childcare plans on behalf of baby” or “talked to friends or relatives about pregnancy, labor, or being a parent.” To avoid numerical problems, .5 was substituted for 0 on all measures employing hours as the metric.

Statistical Model

Each outcome was modeled as a two-equation, seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) system with endogenous variables being wife’s and husband’s outcome scores. SUR employs generalized least squares estimation, which takes account of the cross-equation disturbance covariance to improve efficiency of estimates over those attained under OLS (Greene, 2003). Relative advantage was modeled using a linear spline function with a knot at parity (i.e., the equity point, or a value of zero). This allows the theoretically anticipated nonmonotonic relationship to obtain between relative advantage and each outcome. That is, an increase in relative advantage should be related to an improved outcome among those who are underbenefited. However, beyond the parity point, increasing relative advantage should be associated with a diminished outcome, as being overbenefited also results in distress. A spline function allows an abrupt change in the slope of the relative advantage scale at the parity point (Greene). Tests of restrictions—including cross-equation restrictions—on the parameters were accomplished using the procedures outlined in Wooldridge (2002). Given the small number of minorities, and the absence of any theoretical reason for suspecting race differences in hypothesized effects, analyses are conducted without regard to minority status. Missing values were virtually nonexistent, due to very diligent follow-up of nonresponses by the data collection team. Only four items pertaining to husbands’ hours spent in household or childbirth preparation tasks had a single missing value each. These were replaced with either the valid mean (household chores) or a value of .5 (childbirth preparation).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all study variables. Marital satisfaction is, on average, quite high for both spouses, with wives’ and husbands’ means within one standard deviation of the maximum value. Scores on the love scale were less skewed, but means were still uniformly high. Wives’ and husbands’ reported marital conflict, with means of 5.955 and 5.64, respectively, amid a range of 2 – 11, suggest a moderate level of argumentation. Both depression and anxiety levels appear to be low, particularly for husbands. In sum, outcome scores reflect a relatively happily married and psychologically healthy sample, on average. For both wives and husbands, average general religiousness and sanctification values suggest that religion is important in the life of the typical couple. Most couples have been married for a relatively short period, with an average marital duration of 2.6 years, and are relatively young, with mean ages in the upper twenties. Average family income, at $62,993, places the typical couple squarely in the middle class. Finally, logged contribution ratios suggest that husbands’ contributions exceed wives’ with respect to hours of paid labor, whereas wives’ exceed husbands’ in the other three domains.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Range | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wife’s Outcomes | |||

| Marital Satisfaction | 10 – 21 | 19.539 | 1.875 |

| Love | 65 – 90 | 83.512 | 5.219 |

| Marital Conflict | 2 – 11 | 5.955 | 2.120 |

| Depression | 2 – 25 | 9.825 | 4.217 |

| Anxiety | 0 – 26 | 4.989 | 4.049 |

| Husband’s Outcomes | |||

| Marital Satisfaction | 4 – 21 | 19.258 | 2.131 |

| Love | 50 – 90 | 80.194 | 6.803 |

| Marital Conflict | 2 – 11 | 5.640 | 2.114 |

| Depression | 1 – 21 | 6.596 | 3.717 |

| Anxiety | 0 – 14 | 2.697 | 2.838 |

| Explanatory Variables | |||

| Wife’s Relative Advantage | −7.351 – 13.358 | 0.000 | 2.976 |

| Wife’s General Religiousness | 2 – 16 | 11.101 | 3.917 |

| Wife’s Theistic Sanctification | 10 – 70 | 55.348 | 15.857 |

| Wife’s Nontheistic Sanctification | 10 – 70 | 53.989 | 11.673 |

| Wife’s Age | 19 – 40 | 27.180 | 3.970 |

| Husband’s Relative Advantage | −16.028 – 8.852 | 0.000 | 3.137 |

| Husband’s General Religiousness | 2 – 16 | 10.489 | 4.125 |

| Husband’s Theistic Sanctification | 10 – 70 | 51.889 | 16.706 |

| Wife’s Nontheistic Sanctification | 12 – 70 | 51.917 | 12.229 |

| Husband’s Age | 20 – 42 | 28.725 | 4.438 |

| Number of Years Married | 0.083 – 10.167 | 2.625 | 2.055 |

| Total Family Income in Thousands | 12.500 – 150.000 | 62.993 | 30.155 |

| Logged Education Ratioa | −0.693 – 0.405 | −0.051 | 0.183 |

| Logged Work-Hours Ratioa | −4.605 – 5.075 | 1.061 | 2.077 |

| Logged Childbirth-Preparation Ratioa | −3.401 – 2.618 | −0.411 | 1.153 |

| Logged Housework-Hours Ratioa | −2.890 – 2.944 | −0.029 | 0.815 |

Note: N = 178.

Log of husband/wife contribution.

Seemingly unrelated regressions results for the response variables of love and depression are shown in Table 2. As none of the interactions between religiousness scales and relative advantage were significant for these outcomes, only main-effects models are shown. Models include the full set of control variables, but their effects are not shown in order to conserve space. The model for love reveals that, for both wives and husbands, increases in relative advantage are linked with increasing love for the spouse prior to the parity point (coefficients are .544 for wives and 1.109 for husbands). Both partners show a significant downturn in the slope at parity. For wives, the slope drops .943 units, whereas the drop for husbands is 1.955 units. The resulting slope for relative advantage once past the parity point is therefore negative for both spouses, although only significantly so for husbands. (The post-parity slope is simply the preparity slope plus the slope change at parity.) That is, after parity, increases in relative advantage are associated with lower average love among husbands. For wives, the effect of relative advantage beyond parity is not significant. However, this gender difference is only suggestive. Statistical tests fail to reject the null hypothesis that all coefficients related to relative advantage are identical across gender. In sum, the effect of relative advantage is generally to increase love for the spouse up to the parity point, but to decrease it afterwards. This pattern is consistent with the proposition that the most loving relationships are those characterized by equitable exchanges.

Table 2.

Generalized Least Squares Estimates (Standard Errors) for Seemingly Unrelated Regressions Models of Love and Depression

| Predictor | Love

|

Depression

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | H | W | H | |

| Relative Advantage, Pre-parity | 0.544*a (0.275) | 1.109***a (0.248) | −0.421*a (0.213) | 0.042a (0.149) |

| Slope Change at Parity | −0.943*b (0.437) | −1.955***b (0.421) | 1.378***b (0.339) | 0.290c (0.252) |

| Relative Advantage, Post-parity | −0.399c | −0.846**c | 0.957***d | 0.332*e |

| Disturbance Correlation | 0.245 | 0.225 | ||

| OLS R2 | 0.108 | 0.261 | 0.186 | 0.117 |

Note: N = 178. W denotes wife’s outcome. H denotes husband’s outcome. Coefficients with the same letter superscripts in a given row, for a given outcome, are not significantly different. All models control for logged husband/wife contribution ratios in education, paid work, housework, and childbirth preparation; general religiousness; theistic and nontheistic sanctification; spouses’ ages, number of years married, and total family income.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The results for depression are similar in spirit, especially for women. Their depressive symptomatology decreases by .421 units, on average, with each unit increase in relative advantage prior to parity. At parity, there is a significant increase in the slope of relative advantage of 1.378 units. Each unit increase in relative advantage beyond parity for women is then associated with a .957 unit increase in average depressive symptomatology. For men, neither the effect of relative advantage before parity nor the change in the slope at parity is significant. However, each unit increase in relative advantage past parity is associated with a .332 unit increase in average depressive symptomatology. Statistical tests suggest that the positive change in the effect of relative advantage at parity and the positive slope of relative advantage past parity are significantly stronger for women than for men. In other words, women’s depressive symptomatology is more sensitive to the perception of overbenefit than men’s.

Table 3 presents results for the regression of marital satisfaction, marital conflict, and anxiety. For all three responses, significant interactions obtained between the sanctification or general religiousness scales and relative advantage in their effects. Therefore we present interaction models for these three responses. Only one or the other type of sanctification was a significant moderator in the models for marital satisfaction and conflict. However, all three religiousness scales demonstrated significant interaction effects for anxiety. Nonetheless, the nature of the effect—religiousness buffering the effect of relative advantage on wives’ anxiety—was the same in each case. Hence, we have elected to show only the strongest of the three moderation effects, that for theistic sanctification, in the table.

Table 3.

Generalized Least Squares Estimates (Standard Errors) for Seemingly Unrelated Regressions Models of Marital Satisfaction, Marital Conflict, and Anxiety

| Predfictor | Marital Satisfaction

|

Marital Conflict

|

Anxiety

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | H | W | H | W | H | |

| Relative Advantage, Pre-parity | 0.298**a (0.110) | 0.278**a (0.093) | −0.013a (0.116) | −0.214*a (0.083) | 0.076a (0.228) | 0.096a (0.125) |

| Slope Change at Parity | −0.499**b (0.172) | −0.361*b (0.154) | 0.079b (0.175) | 0.339*b (0.136) | 0.648b (0.346) | 0.102b (0.205) |

| Relative Advantage, Post-parity | −0.201*c | −0.083c | 0.066c | 0.125c | 0.724***c | 0.198d |

| Relative Advantage, Pre-parity × Nontheistic Sanctification | −0.017*d (0.008) | −0.005d (0.011) | ||||

| Slope Change at Parity × Nontheisitic Sanctification | 0.034*e (0.015) | 0.007e (0.015) | ||||

| Relative Advantage, Pre-parity × Theistic Sanctification | 0.003d (0.006) | 0.013*d (0.007) | 0.039**e (0.012) | −0.008f 0.010) | ||

| Slope Change at Parity × Theistic Sanctification | 0.000e (0.011) | −0.017e (0.010) | −0.078***g (0.022) | 0.005h (0.014) | ||

| Disturbance Correlation | 0.225 | 0.455 | 0.230 | |||

| OLS R2 | 0.184 | 0.135 | 0.169 | 0.218 | 0.207 | 0.120 |

Note: N = 178. W denotes wife’s outcome. H denotes husband’s outcome. Coefficients with the same letter superscripts in a given row, for a given outcome, are not significantly different. All models control for logged husband/wife contribution ratios in education, paid work, housework, and childbirth preparation; general religiousness; theistic and nontheistic sanctification; spouses’ ages, number of years married, and total family income.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

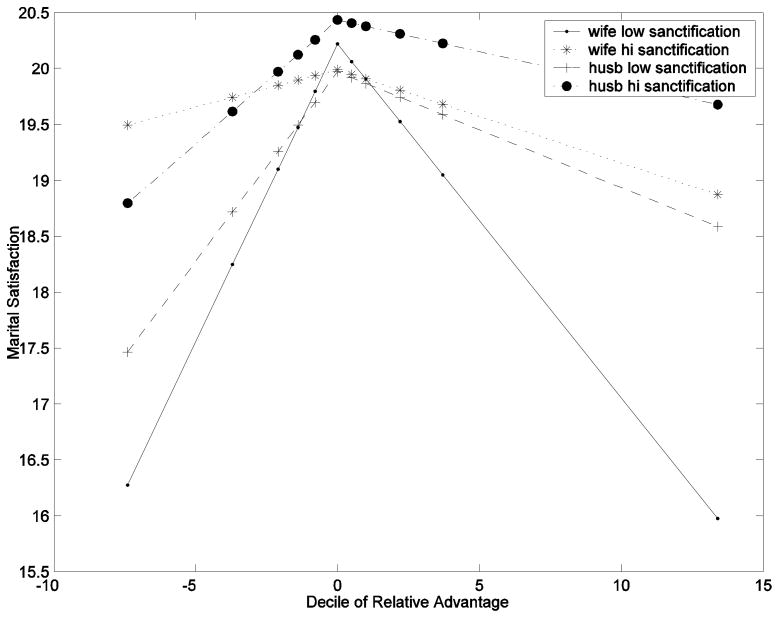

The model for marital satisfaction demonstrates an effect of relative advantage for both spouses that is consistent with expectation. Before the parity point, a unit increase in relative advantage elevates average marital satisfaction by .298 units for wives and .278 units for husbands. These values become significantly more negative at parity, so that after parity, each unit increase in relative advantage reduces mean marital satisfaction for wives by about two-tenths of a unit. For husbands, the post-parity slope is also negative, but not significant. Although the gender difference is, again, suggestive, it cannot be validated statistically. The aforesaid effects, on the other hand, are for those with average levels of nontheistic sanctification. For wives, but not husbands, there is a significant interaction between relative advantage and nontheistic sanctification. The nature of the interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 1. For wives who are low—i.e. one standard deviation below the mean—in sanctification, relative advantage has a strong positive effect on marital satisfaction before the parity point and a strong negative effect after the parity point. For wives who are high—i.e. one standard deviation above the mean—in sanctification, on the other hand, the effect of relative advantage both before and after parity is substantially weaker.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Nontheistic Sanctification with Relative Advantage in Effects on Marital Satisfaction

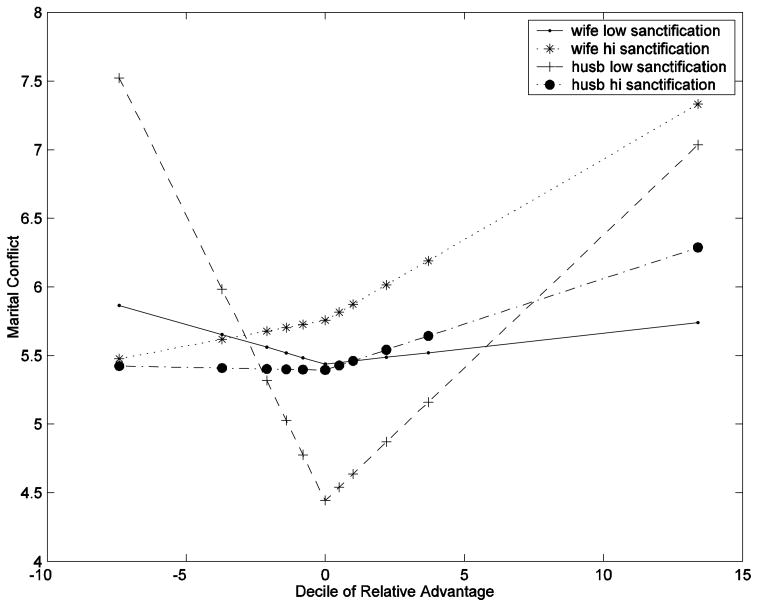

The second pair of columns in Table 3 presents results for marital conflict. A significant effect of relative advantage and a significant interaction effect involving theistic sanctification are found only for husbands. For them, each unit increase in relative advantage before parity reduces average reported conflict by .214 units. At parity, there is a significant positive increase in the slope of relative advantage. However, the post-parity slope, although positive, is nonsignificant. These results pertain to husbands who are characterized by average theistic sanctification. The pre-parity negative effect of relative advantage on conflict is seen to be diminished in magnitude for husbands who are higher sanctifiers. Figure 2 shows the nature of the interaction. For men, but not women, there is a significant buffering effect of theistic sanctification, such that the pre-parity effect of increasing relative advantage on marital conflict is significantly weaker among the higher sanctifiers, compared to others. Once again, however, gender differences in model coefficients are not supported by formal tests.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Theistic Sanctification with Relative Advantage in Effects on Marital Conflict

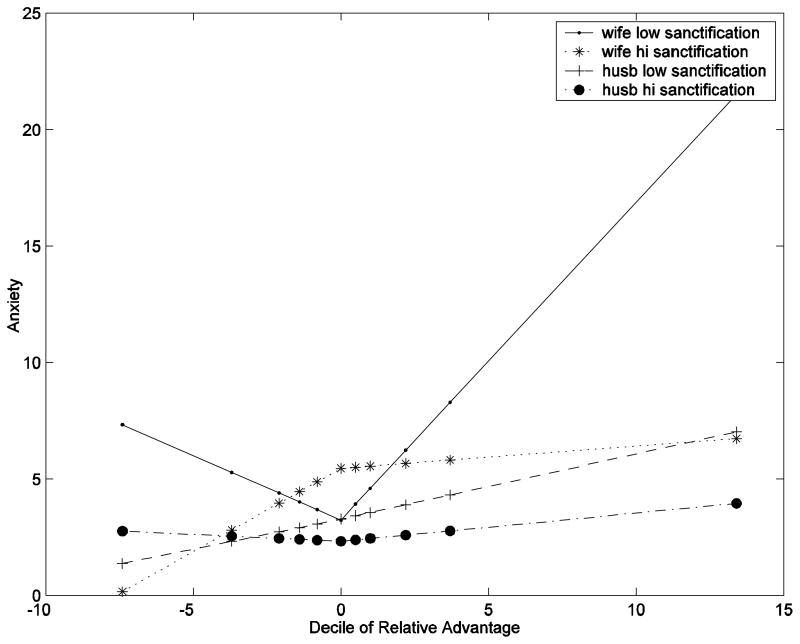

The final pair of columns in Table 3 presents results for anxiety. For both genders who are average sanctifiers, effects of increasing relative advantage prior to parity as well as slope changes at parity are not significant. However, for wives, but not husbands, the effect of increasing relative advantage beyond parity significantly elevates average anxiety level. This gender difference is supported statistically, as well. In other words, wives of average sanctification appear to become increasingly anxious the greater their perception of being overbenefited. This is not the case for husbands. Moreover, there is a significant interaction between relative advantage and theisitic sanctification for wives, but not husbands. This is again reinforced statistically, since interaction coefficients are significantly different for wives vs. husbands. Figure 3 illustrates the nature of the interaction effect. The buffering influence of sanctification is readily seen after parity. The effect of relative advantage is markedly positive for low-sanctifying wives but nearly flat for high sanctifiers. In sum: wives’ anxiety level is adversely affected by their being overbenefited among low sanctifiers. But for higher sanctifiers, being overbenefited has little effect on anxiety.

Figure 3.

Interaction of Theistic Sanctification with Relative Advantage in Effects on Anxiety

Discussion

In this study we re-examined the relevance of inequity in marriage for couples expecting the birth of their first child. This is a group for whom equity considerations would be expected to be of minimal importance. Instead, we found that perceived inequity was associated with diminished marital quality and psychological well being among both husbands and wives. Whether it was more problematic to be advantaged or disadvantaged by the marital exchange varied across both outcome and gender. Exchange imbalances in either direction were associated with less love among husbands, and lower marital satisfaction and more depression among wives. On the other hand, increases in one’s relative advantage were only associated with more love among underbenefited wives, and with more marital satisfaction and less reported conflict among underbenefited husbands. Greater relative advantage was predictive of elevated depression among overbenefited husbands, and heightened anxiety among overbenefited wives. Husbands’ anxiety was not responsive to either under- or overbenefit. These results are consistent with theory as well as with the findings of several previous studies of intimate relationships (Adams, 1965; Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; Hatfield et al., 1978; Lennon & Rosenfield, 1994; Longmore & DeMaris, 1997; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990). Although others have found underbenefiting to be more problematic than overbenefiting (Longmore & DeMaris, 1997; Sprecher, 1986, 1992, 2001), this study suggests that both types of inequity take a toll on well-being. Hence, our hypothesis regarding the relevance of equity considerations in marriage was supported. But the prediction that underbenefting would be more salient was not.

Our hypothesis about women being more affected by inequity than men tended to receive some statistical support. The post-parity effect of relative advantage on both depression and anxiety was significantly stronger for women than men. In both instances, wives’ psychological well-being appeared to be more adversely affected than men’s by being overbenefited. Much prior work has found that relationship outcomes are more responsive to women’s than men’s sense of injustice (Buunk & Van Yperen, 1991; DeMaris, 2007; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Grote & Clark, 2001; Sprecher, 2001; Van Yperen & Buunk, 1991). Yet, although several scholars have found women to be more likely than men to report being underbenefited, few other studies find that women are more negatively impacted by being overbenefited. Further investigation of this phenomenon is warranted in future research.

We had tendered three hypotheses about the role of the sanctification of marriage and general religiousness in buffering the effects of inequity. All three received some support. Consistent with prediction, the adverse effects of perceived inequity were less for those who perceived their marriage as being divine in nature for the outcomes of marital satisfaction, marital conflict, and anxiety. In contrast, general religiousness operated as a buffer only for anxiety. With regard to marital outcomes, higher levels of sanctification of marriage diminished the likelihood that perceived injustice was tied to more marital dissatisfaction and conflict. This is consistent with sanctification theory suggesting that people are willing to make sacrifices to preserve and protect aspects of life that are experienced as being connected to God or imbued with sacred qualities (Mahoney et al., 2003). Related religious teachings emphasize that sacred marriages are marked by high levels of commitment and investment for the good of the marriage (Wilcox, 2004; Wilcox & Nock, 2006). Therefore, for those who see marriage in a sacred light, marital happiness is less affected by seeing themselves as falling on the “short end” of their marital bargain. From a values standpoint, this buffering effect can be seen in either a positive or a negative light. On the positive side, greater sanctification of marriage may serve to insulate couples form the acrimony that often arises over equity issues in marriage (Hochschild, 1989). On the negative side, the failure to monitor fairness can readily facilitate the exploitation of one spouse by the other. In any event, that sanctification, in particular, serves to buffer the influence of perceived injustice is a key finding that reinforces previous work (DeMaris, 2008; Hansen, 1987; Wilcox & Nock, 2006).

On the other hand, our findings also show that greater sanctification buffers spouses against marital distress and anxiety typically created when one feels overbenefited in marriage. This intriguing and novel finding highlights that the internal calculus by which spouses evaluate the benefits of marriage may shift considerably when God enters the picture. Namely, those who view God as partly, or mostly, responsible for the marriage may believe there is no way to give enough to their spouse to balance out feeling overbenefited by God’s unearned largesse. Stated differently, a spouse could feel paradoxically undeserving of the “sacred gift” of being married to the spouse, but nevertheless untroubled by accepting this experience, because to reject God’s actions would also be wrong from a religious perspective.

Further, in accord with prediction, sanctification of the marriage, whether of the theistic or nontheistic complexion, appeared to be a more important moderator than general religiousness. Others have previously noted the salience of marital sanctification over general religiousness as a predictor of marital outcomes (Mahoney et al., 1999). Likewise, here we see that sanctification of marriage offers a more compelling perspective about equity and religiousness than conventional indications of religious involvement that may have little, if anything, to do with marital functioning.

Finally, of the five interaction effects between religiousness and overbenefit that emerged in analyses, four pertained to wives’ outcomes. Hence, our hypothesis about the buffering effect of religiousness being stronger for wives than husbands received some support. As Wilcox and Nock (2006) observe, women are particularly sensitive to the emotional tenor of their marriages. This is partly a result of differential gender socialization that encourages female proficiency in intimacy (Vangelisti & Daly, 1997). And it is partly a function of wives’ traditional responsibility as the stewards of a family’s socioemotional resources. Wives are, as a consequence, more attentive to issues of fairness and more negatively impacted by inequity in marriage than men (Wilcox & Nock, 2006), while at the same time being more religious (Miller & Stark, 2002). Therefore, they are more likely than men to both hear and heed religious messages that focus attention on communitarian, rather than individual, interests.

Despite the confirmation of several of our hypotheses, our results are tempered by some limitations. Perhaps most importantly, the data were collected via a nonprobabilitistic sampling scheme that relied heavily on local sources. Therefore, findings are not necessarily generalizable to all married couples in the U.S. Rather, they probably reflect a more narrowly circumscribed group of recently-married, middle-class, pregnant couples for whom spirituality is at least somewhat relevant. Additionally, due to a small group size for minority couples, we were unable to explore potential race differences in equity dynamics. Finally, inferences regarding the causal priority of perceived inequity vis a vis marital and psychological distress must be tentative, as the data are nonexperimental, as well as cross-sectional. Nevertheless, we argue that the perception of inequity largely precedes the experience of distress. That inequity induces distress is not only supported by experimental studies (Adams, 1965; Hatfield, et al., 1978). But as others have observed, that marital or psychological distress could induce a perception of being overbenefited is not particularly plausible (Van Yperen & Buunk, 1990).

Equity theory has received substantial support in a variety of social venues. The current study adds to the evidence that it is also relevant in marriage. The prevailing ethos of expressive individualism, coupled with an emphasis on gender egalitarianism in marriage, provides spouses a rationale for a close monitoring of the marital exchange (Wilcox & Nock, 2006). Given the pervasive influence of religiousness and spirituality in American society, it is not surprising that these factors play a role in the calculus of equity in marriage. Those more deeply embedded in religious cultures subscribe to a less individualistic approach. Or, at the least, their well-being is less responsive to their perceptions about the fairness of the relationship. Moreover, because women are at once more religious and more sensitive to equity concerns than men, the buffering influence of religiousness is more pronounced for them. Nevertheless, these findings should be replicated in subsequent studies using a more representative sample. Additionally, it would be of interest to investigate whether the long-term effect of inequity on the risk of marital disruption (DeMaris, 2007; Frisco & Williams, 2003; Joyner, in press) is also lower for the more religious. More research needs to be undertaken before we can have a complete understanding of the conditions under which inequity promotes marital distress.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Templeton Foundation, Grants 10976, 11604, 11605, awarded to Annette Mahoney, Kenneth I. Pargament and Alfred DeMaris.

Contributor Information

Alfred DeMaris, Department of Sociology., Bowling Green State University.

Annette Mahoney, Department of Psychology., Bowling Green State University.

Kenneth I. Pargament, Department of Psychology., Bowling Green State University.

References

- Adams JS. Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Tension between institutional and individual views of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:959–965. [Google Scholar]

- Braiker H, Kelley H. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess R, Huston T, editors. Social exchange and developing relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Van Yperen NW. Referential comparisons, relational comparisons, and exchange orientation: Their relation to marital satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17:709–717. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:848–861. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A. The role of relationship inequity in marital disruption. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:177–195. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A. The trajectory of marital quality in enduring marriages: does equity matter? 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaris A, Longmore MA. Ideology, power, and equity: Testing competing explanations for the perception of fairness in household labor. Social Forces. 1996;74:1043–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee D, Sprecher S, Bassin E. The dissolution of intimate relationships: A hazard model. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1990;53:13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Frisco ML, Williams K. Perceived housework equity, marital happiness, and divorce in dual-earner households. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, Sanchez L. Two as one? Couples’ perceptions of time spent together, marital quality, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 5. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Clark MS. Perceiving unfairness in the family: Cause or consequence of marital distress? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:281–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen GL. The effect of religiosity on factors predicting marital adjustment. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1987;50:264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Utne MK, Traupmann J. Equity theory and intimate relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. New York: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Rapson RL, Aumer-Ryan K. Social justice in love relationships: Recent developments. Social Justice Research. 2008;21:413–431. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Walster GW, Berscheid E. Equity: theory and research. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild A. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking; 1989. (with Machung, A.) [Google Scholar]

- Holmes JG, Levinger G. Paradoxical effects of closeness in relationships on perceptions of justice: An interdependence-theory perspective. In: Lerner JJ, Mikula G, editors. Entitlement and the affectional bond. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K. Justice and the fate of married and cohabiting couples. Social Psychology Quarterly. doi: 10.1177/019027250907200106. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The Conflicts and Problem-Solving Scales. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:545–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijer RG, Buunk BP, Ybema JF. Are equity concerns important in the intimate relationship when one partner of a couple has cancer? Social Psychology Quarterly. 2001;64:167–282. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Cobb RJ, Rothman AD, Rothman MT, Bradbury TN. Marital satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:41–50. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon MC, Rosenfield S. Relative fairness and the division of housework: The importance of options. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;100:506–531. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, DeMaris A. Perceived inequity and depression in intimate relationships: The moderating effect of self-esteem. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1997;60:172–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lujansky Harald, Mikula G. Can equity theory explain the quality and the stability of romantic relationships? British Journal of Social Psychology. 1983;22:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A. Religion and conflict in marital and parent-child relationships. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, DeMaris A. Pregnancy and marriage through the lens of the sacred: A descriptive study of a community sample of pregnant married couples. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Jewell T, Swank AB, Scott E, Emery E, Rye M. Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marital functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Murray-Swank A, Murray-Swank N. Religion and the sanctification of family relationships. Review of Religious Research. 2003;44:220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Swank AB. Religion in the home in the 1980s and 1990s: A meta-analytic review and conceptual analysis of links between religion, marriage, and parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:559–596. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AS, Stark R. Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107:1399–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Swank AB, Mahoney A, Pargament KI. Sanctification of parenting: Links to corporal punishment and parental warmth among Biblically conservative and liberal mothers. 2005. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Mahoney A. Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm WR, Paff-Bergen LA, Hatch RC, Obiorah JMC, Meens LD, Bugaighis MA. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48:381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL, Gager CT, Morgan SP. Identifying underlying dimensions in spouses’ evaluations of fairness in the division of household labor. Social Science Research. 1998;27:305–327. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR, Schott TL, Awalt SJ, Gillis-Knox J. Marital satisfaction in pregnancy: Stability and change. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. The relation between inequity and emotions in close relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1986;49:309–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. How men and women expect to feel and behave in response to inequity in close relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1992;55:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Equity and social exchange in dating couples: Associations with satisfaction, commitment, and stability. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:599–613. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JA, Bumpass LL, Call V. The design and content of the National Survey of Families and Households. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Center for Demography and Ecology; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Van Yperen NW, Buunk BP. A longitudinal study of equity and satisfaction in intimate relationships. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;20:287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Vangelisti AL, Daly JA. Gender differences in standards for romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Veijola J, Jokelainen J, Laksy K, Kantojarvi L, Kokkonen P, Jarvelin MR, Joukamaa M. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 in screening DSM-III-R axis-I disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;57:119–123. doi: 10.1080/08039480310000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB. Soft patriarchs, new men: How Christianity shapes fathers and husbands. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox WB, Nock SL. What’s love got to do with it? Equality, equity, commitment and women’s marital quality. Social Forces. 2006;84:1321–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]