Abstract

Acquired pendular nystagmus (APN) occurs with multiple sclerosis (MS) and oculopalatal tremor (OPT); distinct features of the nystagmus have led to the development of separate models for the pathogenesis. APN in MS has been attributed to instability in the neural integrator, which normally ensures steady gaze. APN in OPT may result from electrotonic coupling between neurons in the hypertrophied inferior olivary nucleus, which induces maladaptive learning in cerebellar cortex. We tested these two hypotheses by analyzing the effects of gabapentin, memantine, and baclofen on both forms of nystagmus. No drug changed the dominant frequency of either form of APN, but the variability of frequency was affected with gabapentin and memantine in patients with OPT. The amplitude of APN in both MS and OPT was reduced with gabapentin and memantine, but not baclofen. Analyzing the effects of drug therapies on ocular oscillations provides a novel approach to test models of nystagmus.

Keywords: cerebellum, inferior olive, plasticity, learning, Guillain–Mollaret triangle, multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Acquired pendular nystagmus (APN) consists of ocular oscillations that are often visually disabling, because they induce excessive motion of images on the retina.1 Although a number of neurological disorders have been reported to cause APN, it most commonly occurs in central demyelination disorders, especially multiple sclerosis (MS)2 and as a component of the syndrome of oculopalatal tremor (OPT).3 In both, the APN is often characterized by oscillations with variable horizontal, vertical, and torsional components. However, these two forms of APN also show distinctive differences. APN in MS usually consists of oscillations at a single frequency (3–5 Hz)4 that are either transiently stopped or “reset” (phase-shifted) by large saccades.5,6 APN in OPT often consists of irregular oscillations with a frequency of 1–3 Hz.7,8 Consideration of these findings and the locations of associated neurological lesions have led to the development of distinct hypotheses to account for the mechanism underlying APN in MS versus OPT.

It was hypothesized that the oscillations of APN in MS arise from an unstable neural integrator, which normally ensures steady gaze-holding.6 Such patients often show brainstem lesions on MRI2 that could involve cell groups of the paramedian tracts (PMT), which relay a copy of most ocular motor signals back to the cerebellar flocculus9 and thereby contribute to normal gaze-holding function. Arnold and colleagues10 showed that injection of the hyperpolarizing agent muscimol at the putative site of neural integrator made it more unstable, while injection of a depolarizing agent (glutamate) reversed the effect. We hypothesize that the degree of instability of the neural integrator, which is determined by the excitability of the network neurons, determines the amplitude of APN. This suggests that drugs that can depolarize the cells of the neural integrator would reduce the amplitude of the APN. Reducing the Purkinje cell–induced GABAergic inhibition is the safe way to depolarize the neural integrator in human patients. Gabapentin and memantine can reduce the GABAergic inhibitory influence of cerebellar Purkinje neurons, gabapentin by blocking the alpha-2-delta subunit of calcium channels and both drugs by antagonizing NMDA receptors.11–13 Therefore, these drugs can indirectly depolarize the cells of the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi (and thereby make the neural integrator less unstable) and reduce the amplitude of APN in patients with MS. We also hypothesize that baclofen, a GABAergic drug that hyperpolarizes the cell membrane, may not reduce the amplitude of APN and may even increase it.

APN in OPT is attributed to hypertrophic degeneration of the inferior olivary nucleus (IO) following a breach in the “Guillain–Mollaret triangle,” which comprises connections between the IO and deep cerebellar relay nuclei (DCRN), via climbing fiber axon collaterals, and between DCRN and IO, via the superior cerebellar peduncle and central tegmental tract.3,14–19 Following a lesion, usually of the central tegmental tract, gap junctions (connexins), which are normally restricted to the dendrites of IO, develop between adjacent neural cell bodies. Consequently, local patches of IO neurons begin to fire in synchrony and act as “pacemakers.” The pacemaker output pulses are small and jerky, but learning by the cerebellar cortex smoothes and amplifies them in the DCRN—the dual-mechanism hypothesis.8,20 We propose that drugs affecting the IO output, such as memantine blocking of NMDA receptors,21, would reduce the amplitude of APN. Drugs reducing the output of the cerebellum, such as gabapentin and memantine, 11–13 would reduce the amplitude and frequency variability of the nystagmus waveform, but not the fundamental frequency of APN.

The goal of this study was to measure the effects of drugs known to influence APN in MS or OPT (i.e., gabapentin, memantine, and baclofen), using them as tests of the two hypotheses summarized above.

Methods

All studies were performed at the Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CVAMC), where 12 patients with APN associated with either MS (6) or OPT (6) were recruited as part of two clinical trials.22,23 All patients studied gave written, informed consent in accordance with the Institutional Review Board of the CVAMC and the Declaration of Helsinki. Common to both trials was a crossover design, in which patients were given both drugs, separated by a washout period. In the study of Averbuch-Heller et al., the two drugs were gabapentin (1200 mg/day) and baclofen (40 mg/day). In the study of Thurtell et al., the two drugs were gabapentin (1200 mg/day) and memantine (40 mg/day). All 12 patients had gabapentin, six had memantine (four with OPT and two with MS), and six had baclofen (four with MS and two with OPT). In both studies, 3-D binocular eye movements were recorded using the magnetic search coil technique; further details can be found in these two papers. High-resolution spectral analysis was used to analyze the frequency content of the oscillations from each patient, but only low frequencies (1–Hz) were used to characterize the waveforms. The power spectrum of the oscillations around each axis was computed from a nonparametric eigenvector algorithm (Matlab®, the Mathworks, Natick, MA; function peig()). To eliminate the leakage of power from the direct coupled component of the signal, we first differentiated and low-pass filtered the signal (Matlab® functions sgolayfilt(x, nFit, nFrame, Dorder), where the order of the polynomial fit was nFit = 3, the window width was nFrame = 11 to 181, depending upon the amount of noise in the data, and Dorder was the first derivative). Each signal also had its mean and linear trend removed (Matlab® function detrend()). Differences among the drug effects were analyzed with nonparametric analysis of variance tests (Matlab® kruskallwallis(), multcompare(), and boxplot() functions, with significance at P < 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals throughout).

Results

Pharmacological test of the unstable neural integrator hypothesis in MS

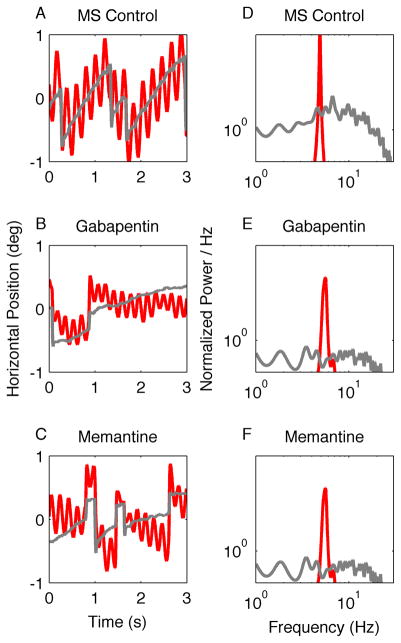

Figure 1A shows horizontal APN in a patient with MS who had binocular jerk nystagmus with a superimposed pendular nystagmus in the right eye. As predicted by the unstable neural integrator hypothesis, the oscillations are regular and have minimal frequency variability, which is reflected by the sharp peak in the power spectrum (Fig. 1D, right eye). The jerk nystagmus had a wide range of frequencies, but present at low power (Fig. 1D, left eye; note double logarithmic scale). Figure 1B and 1C show a reduction in the amplitude of the pendular and jerk nystagmus by gabapentin and memantine. Figure 1E and 1F show the effects of these drugs on the APN power spectrum.

Figure 1.

This is an illustration of the effects of gabapentin and memantine on horizontal APN in one patient with multiple sclerosis (MS). (A–C) Binocular eye positions are plotted against time. Red traces represent the right eye and grey traces the left. The patient has a binocular jerk nystagmus with a superimposed monocular pendular nystagmus in the right eye. The amplitude of both forms of nystagmus is reduced during treatment with gabapentin (B) and memantine (C). Corresponding power spectra are plotted in D–F. The power spectrum of the pendular component is very sharp (D, red trace). The power spectrum of the jerk nystagmus is broader and lower (D, gray trace). Note that both gabapentin and memantine reduce the oscillation amplitude, but do not significantly affect its frequency distribution.

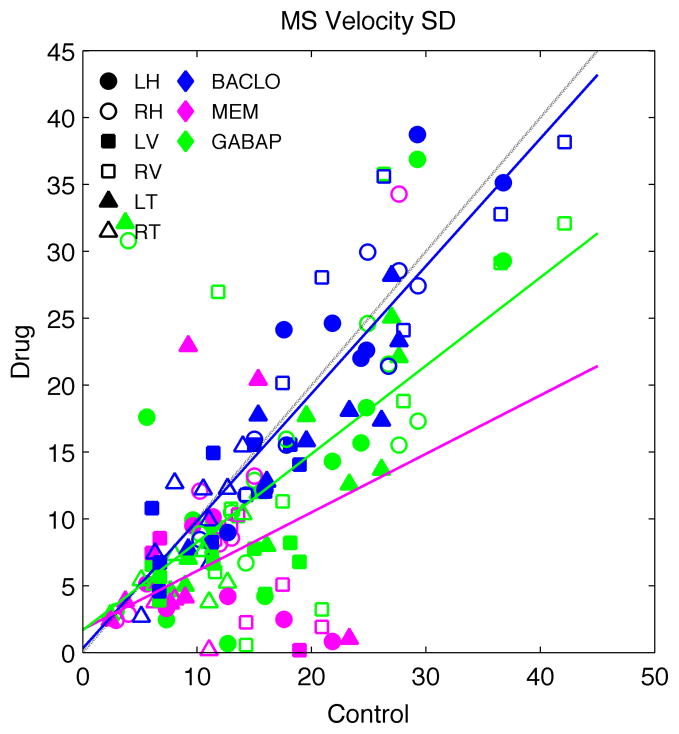

To average across all six patients, all three rotation axes, and both eyes, we needed an estimate of the APN amplitude that was not sensitive to eye position. Thus, we measured the standard deviation (SD) of the each velocity trace. The SD is a measure of the average distance of the peaks and troughs from the mean. The SD does not change with eye-in-orbit position, and is a reasonable measure for inter-subject and inter-axis comparison of the oscillations. The SD of the oscillations and the slope of the jerk nystagmus are both significantly reduced (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.05) for both gabapentin (reductions in SD of ~40%) and memantine (reduction of ~70%), but not for baclofen (Fig. 2). To see whether there was any effect of the drugs on the frequency content of the waveforms, we analyzed the change in the largest peak in the power spectrum (i.e., the dominant frequency). The dominant frequency showed no change (P > 0.05) with any drug. The mean reduction of power at the largest peak was ~30% with gabapentin. Neither memantine nor baclofen had a significant effect on the amplitude of the main spectral peak.

Figure 2.

A scatter diagram of the change in the standard deviation (SD) of the velocity about each axis of rotation (symbols) for each drug (colors) in all six MS patients. Baclofen (BACLO) did not show much effect. In contrast, both gabapentin (GABAP) and memantine (MEM) caused a significant reduction in amplitude (i.e., the standard deviation of the velocity waveform). Regression lines: baclofen = 0.31 + 0.95 * control, R2 = 0.82 (blue line); memantine = 1.73 + 0.44 * drug, R2 = 0.20 (magenta line); gabapentin = 1.68 + 0.66 * control, R2 = 0.45 (green line). Dashed line is the equality line. Symbols indicate left (L) and right (R) eye, and horizontal (H), vertical (V), and torsional (T) movements.

Pharmacological test of the dual-mechanism hypothesis in OPT

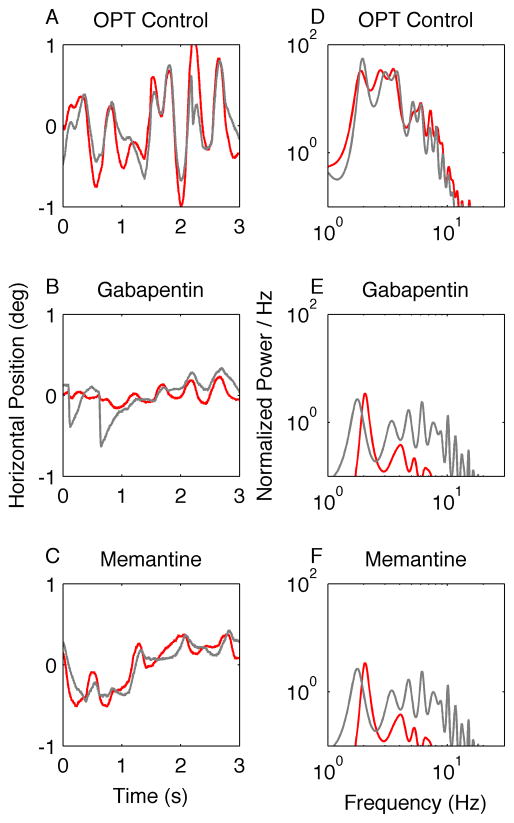

An example of horizontal oscillations from one patient with OPT is shown in Figure 3A. Qualitatively, these oscillations are irregular and smooth, and they are also disconjugate and have idiosyncratic inter-cycle frequency variability. The waveform irregularity, or frequency variability, produces multiple peaks in the power spectrum (Fig. 3D). Gabapentin reduced the amplitude of the oscillations; the waveforms were relatively smoother (Fig. 3B), and the frequency content of the waveform was reduced in both amplitude and range (Fig. 3E). Similar changes were seen with memantine (Figs. 3C and 3F).

Figure 3.

This is an illustration of the effects of gabapentin and memantine on horizontal APN in one patient with oculopalatal tremor (OPT). (A–C) Binocular eye positions are plotted against time. Red traces represent the right eye and grey traces the left. The oscillations are irregular and disconjugate. The amplitude is reduced during treatment with both gabapentin (B) and memantine (C). Corresponding power spectra are plotted in D–F. The power spectrum is very broad, with a large peak around 2 Hz. Note that both gabapentin and memantine reduce the oscillation amplitude and also reduce the irregularity of the waveform (reduction of the range of its frequency distribution).

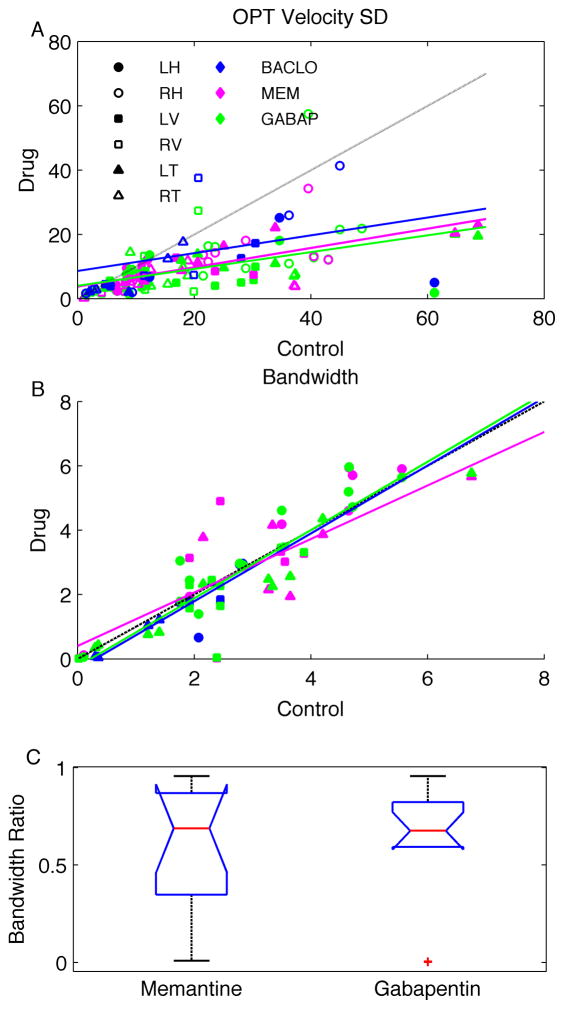

To pool across all patients, rotation axes, and eyes, we again looked at the standard deviation of the velocity traces (Fig. 4). Memantine and gabapentin both significantly reduced APN amplitude by ~70% (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A). The variability of the waveforms with baclofen was quite high, and there was no significant change in amplitude with baclofen (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Panel A shows a scatter diagram of the change in the SD of the velocity about each axis of rotation (symbols) for each drug (colors) in all OPT patients. Only gabapentin and memantine showed a consistent reduction in gain (i.e., the slope between the pre- and post-medication velocity of SDs). Regression lines: baclofen = 8.63 + 0.28 * control, R2 = 0.11 (blue); memantine = 3.77 + 0.30 * drug, R2 = 0.47 (magenta); gabapentin = 3.99 + 0.26 * control, R2 = 0.24 (green). In panel B, the values of the frequency range containing 66% of the power around the dominant frequency (i.e., bandwidth) during treatment with each drug is plotted on the y-axis, while the values prior to treatment are plotted on the x-axis. The dashed line is an equality line. Each data point represents one axis of rotation from one eye in one patient. Right and left eyes are lumped together. Magenta symbols are data after memantine, green symbols are gabapentin, and blue symbols are baclofen. Circles are horizontal component, squares are vertical component, and triangles are torsional component of the data. A broader bandwidth corresponds to more cycle-to-cycle irregularity of the frequency in the given oscillation train. Regression lines: baclofen = −0.32 + 1.05 * control, R2 = 0.81 (blue); memantine = 0.40 + 0.83 * drug, R2 = 0.71 (magenta); gabapentin = −0.24 + 1.06 * control, R2 = 0.89 (green). In panel C, box-and-whisker plots summarize the ratio of bandwidths after and before gabapentin and memantine. The horizontal lines in the center of the notch represent the median ratio, the notches represent 95% confidence intervals, the length of the box represents the inter-quartile distance, and the whiskers represent data range. Red plus symbols represent outliers. Abbreviations as in Fig. 3.

Gabapentin and memantine consistently affected the frequency irregularity in all OPT patients. In order to quantify the frequency irregularity, we computed the bandwidth as the frequency range that contains 66% of the power around the peak of the corresponding power spectrum. In theory, regular oscillations would have a smaller bandwidth, because the power of the waveform would be tightly distributed around the peak. In contrast, irregular oscillations would have a larger bandwidth, because the power would be broadly distributed in the power spectrum. Figure 4B summarizes the effect of the drugs on the bandwidth and, thus, the effects on the oscillation irregularity. Memantine reduced the bandwidth in 47% of instances (magenta symbols, Fig. 4B). Gabapentin reduced the bandwidth in 36% of instances (green symbols, Fig. 4B). Most round symbols, representing the horizontal component of the oscillations, fell above the equality line in Figure 4B; this indicates that, in most cases, gabapentin and memantine did not reduce the bandwidth of the horizontal component of the oscillations. When the horizontal component was excluded, gabapentin reduced the bandwidth in 44% of instances and memantine in 59% of instances. Baclofen reduced the bandwidth in 50% of instances; however, the reduction was minimal in most instances (blue symbols, Fig. 4B). In contrast, with gabapentin and memantine, the reduction was robust in most instances. The amount of reduction in bandwidth was measured by computing the ratio of bandwidths after and before treatment with gabapentin and memantine. A smaller ratio depicts a larger reduction in the bandwidth with the drug. Box and whisker plots in Figure 4C illustrate this ratio, horizontal lines in the center of the notch represent the median ratio (memantine = 0.69 and gabapentin = 0.68), the notches represent 95% confidence intervals, and length of the box represents the inter-quartile distance.

To see whether there was any effect of the drugs on the frequency content of the waveforms, we also analyzed the change in frequency of the largest peak in the spectrum. The dominant frequency showed no change (P > 0.05) with any drug. The mean reduction of power at the largest peak was ~40% for both gabapentin and memantine. Baclofen had no effect on the amplitude of the largest peak (P > 0.05).

Discussion

We set out to test models for two distinct forms of APN: APN associated with MS6 or as a feature of OPT.8 Our strategy was to test predictions that each hypothesis made about the effects of gabapentin, memantine, and baclofen on APN. This requires that we understand what effect each drug has on neurons that are thought to have a role in producing these forms of APN. Current evidence suggests that gabapentin reduces calcium channel trafficking by blocking the alpha-2-delta subunit of the calcium channel.11 A resultant reduction in calcium conductance could reduce the discharge of cerebellar Purkinje neurons24,25 and could block IO gap junctions. Gabapentin and memantine both block NMDA receptors,12,13 which are present in the IO and the cerebellum.21,24,25 Baclofen primarily binds to post-synaptic GABAB receptors. Thus, it enhances the hyperpolarization of neurons receiving input from GABAergic neurons, such as the Purkinje cells.

Pharmacological test of the unstable neural integrator hypothesis for MS

It has been proposed that demyelination of the fibers carrying corollary feedback to the gaze-holding neural integrator, which relay through the paramedian tract cell groups and the cerebellar flocculus, makes the integrator unstable, causing APN.2,6,9 Gabapentin and memantine reduced the amplitude without affecting the frequency of APN in MS patients. Therefore, we speculate that, in MS patients, gabapentin and memantine affected the cerebellar flocculus and, indirectly, its projection site; that is, the neural integrator in the vestibular nuclei and nucleus prepositus hypoglossi.

Injection of the GABA agonist muscimol into the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi hyperpolarizes the cell membranes and makes the neural integrator unstable.10 If APN in MS is indeed caused by an unstable neural integrator (i.e., hyperpolarized nucleus prepositus hypoglossi), the drugs that reduce APN amplitude should depolarize cell membranes. Both drugs might reduce the inhibitory discharge from the cerebellar Purkinje neurons, gabapentin by blocking the alpha-2-delta subunit of calcium channels and both drugs by antagonizing NMDA receptors. The reduction in GABAergic inhibition from Purkinje neurons would then shift the resting membrane potential of the nucleus prepositus hypoglossi towards the depolarized state, thereby making the neural integrator less unstable. Baclofen reduces the excitability of the projection sites of Purkinje neurons, and hence would not shift resting membrane potential away from the hyperpolarized state. It may even make it more hyperpolarized, thus making the neural integrator more unstable and increasing the amplitude of APN. Indeed, we did find more scatter in the responses to baclofen, with some subjects having increased amplitudes (cf. Fig. 2).

Importantly, none of the drugs changed the oscillation frequency. The frequency of oscillation could be determined by multiple mechanisms, such as the increase in feedback delay caused by demyelination and by cells’ membrane adaptation time-constant.26,27 The latter is determined by the gating properties of the ion channels and, thus, the activation kinetics of the cell membrane. As proposed in the above paragraph, increasing the excitability by reducing the inhibitory influence of the Purkinje neurons, without directly affecting the membrane ion channels at the neural integrator, is unlikely to change the membrane activation kinetics. Thus, the oscillation frequency should remain unaffected.

Pharmacological test for the dual-mechanism model for OPT

The dual-mechanism model for OPT predicts that the ocular oscillations of OPT are primarily generated by multiple patches of independent oscillators in the IO. The kinematic properties of these oscillations are then altered by independent patches of cerebellar Purkinje cells, each trying to predict the arrival of an input pulse from one patch of the IO.8 Our results suggest that both gabapentin and memantine blocked NMDA receptors in the cerebellum (at the projection of the IO to the deep cerebellar nuclei, at the projection of the climbing fibers to the Purkinje neurons, and at the projection of the parallel fibers onto the Purkinje neurons). All of these effects would decrease the output of the Purkinje neurons28 and DCRN. According to the predictions of the dual-mechanism model, reducing the output of the cerebellum would result in both reduced oscillation amplitude and waveform frequency variability (see Fig. 3, panels D, E, F, and Figure 4). The dominant frequency, however, is predicted to be set by the intrinsic properties of the IO neurons and, thus, should not change.

Baclofen, which is known to reduce the excitability of pre-motor vestibular neurons via a GABAergic mechanism, did not alter the amplitude, frequency, or frequency variability of OPT. This is also consistent with the dual-mechanism model, which suggests that OPT oscillations are generated by the IO and modulated by the output of the cerebellar Purkinje neurons, but not due to downstream signal modulation by pre-motor neurons in the vestibular nuclei.8

We noticed large variability in the effects of gabapentin, memantine, and baclofen amongst our patients. We suspect that such variability in response to the drug is related to the degree of severity of coexisting lesions (e.g., inter-nuclear ophthalmoplegia or cranial nerve palsies) and genetic build-up of an individual (i.e., variability in the expression rate of various ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors at the targeted neurons, variability in the affinity of the target receptor to the given drug molecule, and the variability in the excretion rate and metabolism of the drug).

To summarize, our analysis of the effects of drugs on APN supports the dual-mechanism model for OPT and the unstable neural integrator model for MS. Much of the anatomy and physiology of the ocular motor system is well understood,1 making it possible to develop detailed models for abnormal eye movements, such as those described in this paper. The growing body of knowledge concerning the neuropharamacology of eye movements provides a new approach for testing current models for the normal and abnormal control of eye movements.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. David S. Zee, Robert L. Tomsak, Avrom D. Epstein, Edward L. Westbrook, and Robert F. Richardson Jr. for collegial support. This study was supported by NIH grant EY06717, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Evenor Armington Fund.

Reference List

- 1.Leigh RJ, Zee DS. Book/CD- rom. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. The Neurology of Eye Movements. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez LI, Bronstein AM, Gresty MA, DuBoulay EP, Rudge P. Clinical and MRI correlates in 27 patients with acquired pendular nystagmus. Brain. 1996;119:465–472. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deuschl G, Toro C, Valls-Solo J, Zee DS, Hallett M. Symptomatic and essential palatal tremor. 1. Clinical, physiological and MRI analysis. Brain. 1994;117:775–788. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.4.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gresty MA, Ell JJ, Findley LJ. Acquired pendular nystagmus: its characteristics, localising value and pathophysiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982 May;45(5):431–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.45.5.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aschoff JC, Conrad B, Kornhuber HH. Acquired pendular nystagmus with oscillopsia in multiple sclerosis: A sign of cerebellar nuclei disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37:570–577. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.37.5.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das VE, Oruganti P, Kramer PD, Leigh RJ. Experimental tests of a neural-network model for ocular oscillations caused by disease of central myelin. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s002210000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong S, Optican LM. Interaction between Purkinje cells and inhibitory interneurons may create adjustable output waveforms to generate timed cerebellar output. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaikh AG, Hong S, Liao K, Tian J, Solomon D, Zee DS, Leigh RJ, Optican LM. Oculopalatal tremor explained by a model of inferior olivary hypertrophy and cerebellar plasticity. Brain. 2010;133:923–940. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Büttner-Ennever JA, Horn AK. Pathways from cell groups of the paramedian tracts to the floccular region. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;781:532–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb15726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold DB, Robinson DA, Leigh RJ. Nystagmus induced by pharmacological inactivation of the brainstem ocular motor integrator in monkey. Vision Res. 1999;39:4286–4295. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thorpe AJ, Offord J. The alpha2-delta protein: an auxiliary subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels as a recognized drug target. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:761–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornhuber J, Weller M, Schoppmeyer K, Riederer P. Amantadine and memantine are NMDA receptor antagonists with neuroprotective properties. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1994;43:91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YS, Chang HK, Lee JW, Sung YH, Kim SE, Shin MS, Yi JW, Park JH, Kim H, Kim CJ. Protective effect of gabapentin on N-methyl-D- aspartate-induced excitotoxicity in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:144–147. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08067sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillain G, Mollaret P. Deux cas myoclonies synchrones et rhythmées vélo-pharyngo-laryngo-oculodiaphragmatiques: Le problèm anatomique et physiolopathologique de ce syndrome. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1931;2:545–566. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deuschl G, Mischke G, Schenck E, Schulte-Monting J, Lucking CH. Symptomatic and essential rhythmic palatal myoclonus. Brain. 1990;113( Pt 6):1645–1672. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.6.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperling MR, Herrmann J. Syndrome of palatal myoclonus and progressive ataxia: Two cases with magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1985;35:1212–1214. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.8.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birbamer G, Gerstenbrand F, Aichner F, Buchberger W, Chemelli A, Langmayr J, Lo PR, Pollicino P, Bramanti P. MR-imaging of post-traumatic olivary hypertrophy. Funct Neurol. 1994;9:183–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyal M, Versnick E, Tuite P, Cyr JS, Kucharczyk W, Montanera W, Willinsky R, Mikulis D. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration: metaanalysis of the temporal evolution of MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1073–1077. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishie M, Yoshida Y, Hirata Y, Matsunaga M. Generation of symptomatic palatal tremor is not correlated with inferior olivary hypertrophy. Brain. 2002;125:1348–1357. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong S, Leigh RJ, Zee DS, Optican LM. Inferior olive hypertrophy and cerebellar learning are both needed to explain ocular oscillations in oculopalatal tremor. Prog Brain Res. 2008;171:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00631-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen LW, Tse YC, Li C, Guan ZL, Lai CH, Yung KK, Shum DK, Chan YS. Differential expression of NMDA and AMPA/KA receptor subunits in the inferior olive of postnatal rats. Brain Res. 2006;1067:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Averbuch-Heller L, Tusa RJ, Fuhry L, Rottach KG, Ganser GL, Heide W, Büttner U, Leigh RJ. A double-blind controlled study of gabapentin and baclofen as treatment for acquired nystagmus. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:818–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurtell MJ, Joshi AC, Leone AC, Tomsak RL, Kosmorsky GS, Stahl JS, Leigh RJ. Crossover trial of gabapentin and memantine as treatment for acquired nystagmus. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:676–680. doi: 10.1002/ana.21991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Friel DD. Impact of the leaner P/Q-type Ca2+ channel mutation on excitatory synaptic transmission in cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2008;586:4501–4515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ovsepian SV, Friel DD. The leaner P/Q-type calcium channel mutation renders cerebellar Purkinje neurons hyper-excitable and eliminates Ca2+-Na+ spike bursts. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaikh AG, Ramat S, Optican LM, Miura K, Leigh RJ, Zee DS. Saccadic burst cell membrane dysfunction is responsible for saccadic oscillations. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;228(4):329–36. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31818eb3a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramat S, Leigh RJ, Zee DS, Optican LM. Ocular oscillations generated by coupling of brainstem excitatory and inhibitory saccadic burst neurons. Exp Brain Res. 2005;160(1):89–106. doi: 10.1007/s00221-004-1989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alev C, Urschel S, Sonntag S, Zoidl G, Fort AG, Hoher T, Matsubara M, Willecke K, Spray DC, Dermietzel R. The neuronal connexin36 interacts with and is phosphorylated by CaMKII in a way similar to CaMKII interaction with glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20964–20969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold DB, Robinson DA. The oculomotor integrator: testing of a neural network model. Exp Brain Res. 1997;113:57–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02454142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starck M, Albrecht H, Pollmann W, Dieterich M, Straube A. Acquired pendular nystagmus in multiple sclerosis: an examiner-blind cross-over treatment study of memantine and gabapentin. J Neurol. 2010;257:322–327. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]