Summary

Severe thermal injury occurs frequently, especially in the low-income countries of the world, where they account for a substantial mortality and a wide range of devastating morbidity. Almost all systems of the body are affected, including the cardiovascular, immune, and reproductive systems. A number of studies have shown that people with severe burns may develop impaired spermatogenesis and testicular damage. However, if we consider the many systems that are negatively affected by burns, the effects on the reproductive system are among the least investigated and are therefore poorly understood. We delineated sperm quality changes in 20 men recovering from severe burn injury. They submitted semen at monthly intervals for analysis over a fourmonth period. Our results show that these subjects had significantly lower total sperm counts than normal for their age range. Sperm counts were 20 million/ml or less in half of the study population with a mean of 26.58 ± 7.52 m/ml. Progressive motility was even more severely affected; the score was less than 20% in more than half of the patients, with a mean of 27.74 ± 7.64. Though abnormal sperm rates were within the normal range, in many of the patients 80% of abnormal cells had swollen, oblong and round heads. Cells with tail anomalies made up the rest. Our findings suggest that severe burns cause significant reduction of sperm density and motility. They also cause specific head abnormalities in the cells produced. Such sperm is now known to have very poor fertilization potential.

Keywords: SPERM, QUALITY, CHANGES, SURVIVORS, SEVERE BURNS

Abstract

Les lésions thermiques graves se produisent fréquemment, surtout dans les pays à revenu bas, où elles sont responsables d'une mortalité élevée et d'une vaste gamme de morbidité dévastatrice. Presque tous les systèmes corporels sont affectés, y compris les systèmes cardiovasculaires, immuns et reproducteurs. Plusieurs études ont montré que les hommes atteints de graves brûlures sont exposés au risque d'une altération de la spermatogenèse et à des dégâts testiculaires. Cependant, si on considère les nombreux systèmes qui sont affectés négativement par les brûlures, on peut constater que les effets sur le système reproducteur n'ont pas été soumis à des études approfondies, et par conséquent ils sont très peu connus. Nous avons donc évalué les modifications dans la qualité du sperme de 20 hommes qui s'étaient rétablis après avoir souffert de graves brûlures. Ils ont fourni du sperme à intervalles mensuels pour être analysé pendant une période quatre mois. Les résultats indiquent que ces sujets présentaient une numération spermatique totale considérablement inférieure aux valeurs normales pour leur tranche d'âge, c'est-à-dire de 20 m/ml ou moins dans la moitié de la population de l'étude (valeur moyenne, 26,58 ± 7,52 m/ml). La motilité progressive a été affectée en manière encore plus notable, avec une valeur de moins de 20 dans plus de la moitié des sujets (valeur moyenne, 27,74 ± 7,64 (m/ml). Même si les valeurs du sperme anormal restaient entre les limites de la normalité, dans un grand nombre des sujets 80% des cellules observées avaient la tête gonflée, oblongue et ronde. Les cellules restantes présentaient des anomalies dans la queue. Nos résultats semblent indiquer que les brûlures graves provoquent une réduction significative dans la densité et la motilité du sperme, comme aussi. Elles causent en outre des anormalités spécifiques dans la tête des cellules produites. On sait maintenant que ce type de sperme possède une potentialité de fécondation très faible.

Introduction

Worldwide, male fertility has dropped steadily over the last several decades, with estimates of over 50% reduction in sperm counts having been reported.1 Although the causes of this decline are by no means clearly understood yet, several factors have been implicated. These include unhealthy lifestyles and occupational hazards, infections, and congenital abnormalities.2,3 In recent years emphasis in research has focused on chemical substances, environmental toxins, endocrine disrupters, and ionizing radiation, all of which have been shown to be capable of disrupting spermatogenesis.4,5

Severe thermal injury produces devastating morbidity spreading across almost all the body systems. Burns cause an inflammatory and cytokine response that is now known to persist for several months into the post-burn period.6 In children, for instance, pathophysiological changes post-burn establish a hypermetabolic state characterized by raised cardiac and respiratory rates and increased breakdown of lipids and protein, with a negative nitrogen balance and reduced lean body mass. The cytokine response shows elevated levels of key markers, especially interleukins, but also including interferon-gamma, monocyte chemoattractant factor-1(MCP-1), and C-reactive protein.6-9 Jeschke et al. have established the fact that apart from the catecholamine response that modulates the shock phase, more widespread changes occur in the endocrine system in burn patients, involving for example thyroid and sex hormones.6 Studies have shown alterations in serum levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone, and testosterone in people with severe burns.10

We and others have shown in a number of studies that testicular damage may occur in people with severe burns.10,11 However, infertility is one of the least studied complications of burns and published studies on it are scanty in the literature we have reviewed. Consequently, little is known about sperm quality and the mechanisms leading to testicular damage in these cases. We therefore studied sperm parameters in men who had recovered from severe burns for several months after their recovery in order to characterize changes in sperm density, progressive motility, and abnormal morphology rates.

Materials and methods

Materials

Twenty adult male patients treated for severe burn injuries over a two-year period and attending follow-up clinics were recruited into this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all entrants. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of our teaching hospital and complied with the requirements of the Helsinki Declaration on human studies, as amended.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: history of significant genitourinary tract infection prior to or during the burn management; burn injury involving the perineum; pre-burn history of metabolic diseases, including diabetes mellitus or goitre, and a previous history of infertility in a married couple, irrespective of the cause and any history of childhood mumps or tuberculosis, past or present.

Methods

Serial semen samples were collected by masturbation after one week's continence at monthly intervals over a period of 4 months and analysed within 30 minutes in the same laboratory by an experienced but blinded investigator. The procedure applied followed current WHO guidelines for analysing human semen. The result for each patient was taken as the mean of these four measurements. Samples were analysed for total sperm count, progressive motility, and abnormal sperm rate.

Results

Demographics

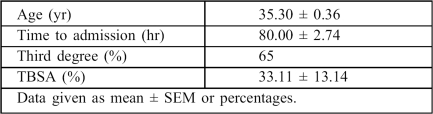

The patient's ages ranged between 25 and 53 yr (mean, 35.3 ± 3.26 yr) (Table I). Of the 20 patients, 16 (80%) sustained major burns i.e. burn area in excess of 20% total body surface area (TBSA). The extent of injury ranged from 13 to 60% TBSA, with an overall mean of 33.11 ± 13.14%. Burn depth was full thickness in 13 patients (65%) and partial thickness in 7 (35%).

Table I. Demographics of the twenty subjects.

Sperm parameters

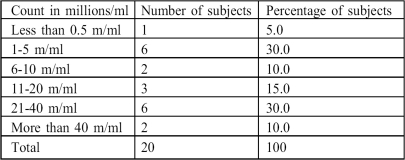

Sperm density ranged from zero to 109 million/ml (m/ml), with a mean of 26.58 ± 7.52 m/ml. Out of the 20 patients, 15 (75%) had a sperm density of less than 40 m/ml. Sixty per cent of the subjects had total counts of 20 m/ml or less (Table II).

Table II. Sperm density.

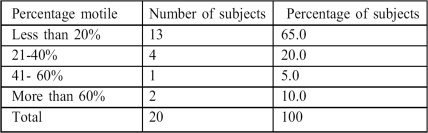

Progressive motility ranged between zero and 80%, with a mean of 27.74 ± 7.64% (Table III).

Table III. Progressive motility scores.

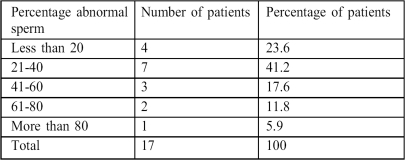

The abnormal sperm rate ranged from 10 to 95%. The majority of the abnormal cells (>80%) had oblong, swollen, and apparently oedematous heads. Tail abnormalities made up the rest (Table IV).

Table IV. Abnormal sperm rates.

Discussion

Our results show that these subjects had significantly lower total sperm counts than expected for a fertile population. The total sperm count was 20 m/ml or less (i.e. clinically oligospermic) in half of the study population. In three-quarters the count was less than 40 m/ml, a figure considered by many as a critical level below which fertility problems begin to be common.12 But probably more significant, in terms of its impact on the fertility status of these individuals, is the finding that the progressive motility score was less than 20% in more than half the patients, since motility and morphology are very important determinants of fertilization and conception potential.13,14 There is no agreement among researchers on how sperm parameters predict fertility15-17 and the usefulness of the WHO reference figures is currently seriously disputed.18 Few however will doubt that, at least in unaided situations, a critical level of normally shaped sperm is required for conception, irrespective of total counts.16

It is also widely believed that the threshold total count below which fertility problems become likely is around 40 m/ml.12 In a rigorously designed comparison of a fertile and a subfertile population, Menkveld et al.16 found the best discriminating parameter to be sperm morphology. The critical cut-off point in that study was 31% for morphology and 45% for motility, using WHO criteria. Other studies have however queried the predictive power of sperm morphology, favouring sperm density and motility.19

Optimum levels of sperm production require precise physical and biochemical homeostasis as well as appropriate endocrine stimulus - for example, in most mammals, including man, any sustained elevation of intrascrotal temperature above a certain level disrupts spermatogenesis.20,21

The few studies published so far on burn-related infertility suggest that testicular damage may occur in severely burned men.10,22 The precise mechanisms by which this damage occurs are yet to be fully elucidated. Several processes are likely to be involved. Severe burns cause a significant alteration in a wide range of biochemical and endocrine markers of the biological milieu which initiate a sustained inflammatory reaction that is now known to continue for several months into the post-burn period. In children at least this leads to wasting and a negative nitrogen balance and may cause testicular atrophy.

Jeschke et al.6 have demonstrated wide-ranging changes in the cytokine profile of burned children. Of 17 cytokines assayed in their study, there was a drastic increase in the serum levels in 16 of them, especially IL6, IL8, MCP-1, and MIP-1-beta.6 There is also considerable alteration of immune responsiveness in burn victims.23

A marked alteration of function has been demonstrated in the hypothalamo-pituitary organ axis after major burns.24,25 Some studies have reported alterations in serum levels of reproductive hormones with a fall in testosterone and FSH which was difficult to reverse with chorionic gonadotropin in the severely burned.10 Others have reported a fall in testosterone levels accompanied by rising estradiol and progesterone levels.10,22 Such a configuration will compromise the hormone support needed for optimum spermatogenesis. In the seminiferous epithelium, Sertoli cells are FSH-dependent. Sertoli cells secrete clusterin, which is now known to mediate many cell-to-cell interactions critical to many of the later stages of spermatogenesis.26

In our study the abnormal cell rate compared well with that in the general population. In 17 out of the 20 patients (85%), there were abnormal sperm rates of 60% or less. There was however a preponderance of head abnormalities, with swollen, oblong, and round heads constituting about 80% of the abnormal cells seen. Tail anomalies made up the rest. However, swollen heads imply oedema, unravelling chromosomes, and DNA damage, a process that renders sperm functionally worthless, since sperm penetration and other critical early events in the conception process are impaired if the integrity of the membrane or the DNA in the head area are compromised.27,28

The progressive motility score was less than 40% in more than three-quarters of the subjects. Peroxidation of fatty acids in sperm plasma membrane has been shown to impair fluidity and fertilizing ability.29 Circulating cytokines and other mediators of inflammation released after burns probably alter membrane permeability in the head region, exposing DNA to toxic damage.

We noticed that semen samples in most of the subjects yielded positive cultures of pathogenic organisms. This was most likely due to the effects of urethral catheterization, which is practised in the early stages of managing patients with severe burns. Although this would amount to contamination of the semen by urethral organisms rather than infection of the testes, studies are required to determine the contribution, if any, of such urethral infection to the reduced fertility seen in these subjects.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we confirmed in this study the findings of previous investigators that there is a statistically significant reduction in key indices of sperm quality in severely burned people. We also delineated a specific type of sperm head abnormality as the preponderant morphological finding in the samples studied. Studies are needed in order to elucidate the pathways of testicular suppression in these subjects and to design effective action against the problem.

References

- 1.Carlsen E., Giwercman A.J., Kieding N., Skakkebaek N.E. Evidence for decreasing quality of semen during the past 50 years. BMJ. 1992;305:609–613. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6854.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valencia A., Ortega B., Campos G., Ponce-Monter Environmental temperature and cryptorchidism: Effects of pregnenolonesulfatase on mice testicular tissue. Arch. Androl. 2003;36:233–238. doi: 10.3109/01485019608987100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar A., Ghadir S., Eskandar N., De Cherney A.H.De CherneyCurrent Diagnosis and Treatment. Obstetrics and Gynecology New York: McGraw Hill; 10thed.2007917–920. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waring R.W., Harris R.M. Endocrine disrupters: A human risk? Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2005;244:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li L.H., Jester W.F., Laslet A.I., Orth J.M. A single dose of di(2 ethylhexyl)phthalate in neonatal rats alters gonocytes, reduces Sertoli cell proliferation and decreases cyclin D2 expression. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000;166:222–229. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeschke M.G., Chinkes D.L., Finnerty C.C., Kulp G., Suman O.E., Norbury W.B., Branski L.K., Gauglitz G.G., Mlcak P.R., Herndon D.N. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann. Surgery. 2008;234:387–398. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herndon D.N., Tompkins R.G. Support of the endocrine response to burn injury. Lancet. 2004;361:1895–1902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finnerty C.C., Herndon D.N., Przkora R., Pereira C.T., Oliveira H.M., Quiroz D.M., Rocha M.C., Jeschke M.G. Cytokine expression profile over time in severely burned pediatric patients. Shock. 2006;26:13–19. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000223120.26394.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwacha M.G., Chaudry I.H. The cellular basis of post-burn immunosuppression: Macrophages and mediators. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002;10:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolecek R., Dvoracek C., Jezek M., Kubis M., Sajnar J., Zavada M. Very low testosterone levels and severe impairment of spermatogenesis in burned male patients. Correlations with basal levels of FSH, LH and PRL after LHRH + TRH. Endocrinol. Exp. 1993;1:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fadeyibi I.O., Saalu L.C., Jewo P.I., Benebo A.S., Ademiluyi S.A. Histopathological patterns of the testes in patients with severe burns not involving the perineum (A case series study). Trends in Medical Research. 2009;4:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonde J.P., Ernst E., Jensen T.K., Hjollund N.H., Kilstad H., Henriksen T.B., Scheike T., Giwercman A., Olsen J., Skakkebaek N.E. Relation between semen quality and fertility: A population-based study of 430 first-pregnancy planners. Lancet. 1998;352:1172–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzick D.S., Overstreet J.W., Factor-Litvak P., Brazil C.K., Nakajima S.T., Coutifaris C., Carson S.A., Cisneros P., Steinkampf M.P., Hill J.A. et al. National co-operative reproductive medicine network sperm morphology, motility, and concentration in fertile and infertile men. New England J. Medicine. 2001;345:1388–1393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen N., Asklund C., Carlsen E., Skakkebaek N.E. Coordinated European investigations of semen quality: Results from studies of Scandinavian young men are a matter of concern. Int. J. Andrology. 2006;29:54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haugen T.B., Egeland T., Magnus O., Magnus O. Semen parameters in Norwegian fertile men. J. Andrology. 2006;27:66–71. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menkveld R., Wong W.Y., Lombard C.J., Wetzel A.M., Thomas C.M., Merkus H.M. teegers-Theunissen R.P.: Semen parameters, including WHO and strict criteria morphology, in a fertile and subfertile population: An effort towards standardization of in vivo thresholds. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:1165–1171. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.6.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shyam S.R., Allamonem A., Benderanayake I., Agarwa A. Use of semen quality scores to predict pregnancy rates in women undergoing intra-uterine insemination with donor sperm. Fertil. Steril. 2004;82:606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laboratory Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Sperm-Cervical Mucus Interaction New York: Cambridge University Press; World Health Organization4thed.1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nallella K.P., Sharma R.K., Aziz N., Agarwal A. Significance of sperm characteristics in the evaluation of male infertility. Fertil. Steril. 2006;85:629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yavetz H., Harash B., Paz G., Yoger L., Jaffa A., Lessing J., Hommonai Z. Cryptorchidism: Incidence and sperm quality in infertile men. Andrologia. 2000;24:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1992.tb02655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saalu L.C., Jewo P.I., Fadeyibi I.O., Ikuerowo S.O. The effects of unilateral varicocele on the contralateral histomorphology and function in rattus norvegicus. J. Med. Sciences. 2008;7:654–659. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Da M., Ma K., Duan T. Clinical studies on the effects of burn trauma on pituitary-testis axis. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Shao Shang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 1999;5:373–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwacha M.G. Macrophages and post-burn immune dysfunction. Burns. 2003;29:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmieri T.L., Levine S., Schonfield-Warden N. et al. Hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal axis response to sustained stress after major burn injury in children. J. Burn Care Res. 2006;27:172–177. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000238098.43888.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanhorebeck I., Langouche L., Van de Berghe G. Endocrine aspects of prolonged critical illness. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;2:20–31. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey R.W., Aronow B., Harmony J.A., Griswold M.D. Heat shock-initiated apoptosis is accelerated and removal of damaged cells is delayed in the testis of clusterin/ApoJ knock out mice. Biol. Reprod. 2002;66:1042–1053. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson-Cook K.L., Brannian J.D., Hansen K.A., Kasperson K.M., Arnold E.T., Evenson D.P. Relationship between outcomes of assisted reproductive techniques and sperm DNA fragmentation as measured by the sperm chromatin structure assay. Fertil. Steril. 2003;80:895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)01116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z., Wang L., Cai J., Huang H. Correlation of sperm DNA damage with IVF and ICSI outcomes: A systematic review and metanalysis. J. Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 2006;23:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9066-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato M., Makino S., Kinura H., Out T., Nagamura Y. Sperm motion analysis in rats treated with Adriamycin and its application to male reproductive toxicity studies. Toxicol. Sci. 2001;26:51–55. doi: 10.2131/jts.26.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]