Summary

This is a retrospective study of 12 male patients with electrical burns out of 362 patients admitted to the burns unit of the Royal Rehabilitation Centre at King Hussein Medical Centre, Jordan, over a period of four years from January 2004 to December 2007. The commonest cause of the burns was related to human error and lack of knowledge. The average total burn surface area was 30.3%. The average percentage of cases involving limb loss was 41.7% and the mortality rate was 25.0%.

Keywords: ELECTRICAL, BURN, FOUR-YEAR, STUDY

Abstract

Les Auteurs de cette étude rétrospective, qui pendant une période de quatre ans (janvier 2004-décembre 2007) se sont occupés de 12 patients du sexe masculin atteints de brûlures électriques sur 362 patients hospitalisés au Centre Royal de Rééducation du Centre Médical Roi Hussein, Jordanie, ont trouvé que la cause la plus commune du traumatisme était liée à l'erreur humaine et à l'absence des informations nécessaires. La surface corporelle brûlée moyenne était de 30.3%, le pourcentage des patients qui ont subi une perte des membres touchait le 41,7% et le taux de mortalité était 25,0%.

Introduction

Electrical burn injury is one of the most devastating injuries seen in the emergency room. It is a special type of thermal injury with a potentially devastating capacity for functional and aesthetic sequelae. 1, 2, 3It occurs less frequently than scald and direct flame burn. Electrical burn can come from low-voltage or high-voltage currents. The pathophysiology of electrical burn depends on the voltage, current flow, and tissue resistance. 3, 4, 5, 6The damage caused by electrical burn is due to two mechanisms, the local generation of heat and the direct action of the passage of the current itself through the tissue. The heating causes coagulative necrosis of the cells and the current causes cell membrane disruption that leads to tissue loss and death.

Most electrical injuries occur in males at work or in children handling exposed electrical lines, 1, 3, 5, 6and most of them are preventable through proper education.

This study was conducted to review the electrical burn patients admitted to the Burns Unit of the Royal Rehabilitation Centre, King Hussein Medical Centre, Amman, over a period of four years (2004-2007). The patients were analysed with respect to age, sex, site of accident, voltage, clinical presentation, surgical procedures, and outcome.

Methods and materials

During the period from January 2004 to December 2007 all patients with electrical burn admitted to the burns unit of the Royal Rehabilitation Centre at King Hussein Medical Centre were analysed. Patients who arrived dead after electrical burn or those admitted to the general wards were excluded from the study. On arrival the patients were resuscitated and investigated for other associated injuries. Resuscitation began with intravenous fluids according to the Parkland formula, using Ringer’s lactate solution. The patients were then put on H2 blockers and started on intravenous opioids. Antibiotics were not used unless there was evidence of systemic infection or infection on tissue culture

The patients were monitored closely for vital signs, central venous pressure, and urine output. Daily blood investigations for packed cell volume (PCV) and electrolyte disturbances were performed. The urine was examined for myoglobinuria, which was treated upon diagnosis with mannitol and alkalization of the urine. The burn was dressed daily with a topical antibiotic agent: silver sulphadiazine (Flamazine). Fasciotomy was performed in cases with suspected compartment syndrome; the patients then underwent early debridement of devitalized tissue.

The patients were examined daily for the progress of the wounds and further debridement was performed as needed. When the limbs were completely severed, amputations were performed as soon as possible to prevent sepsis. Amputation was justified either clinically or by angiogram in questionable cases, which was also helpful in determining the level of amputation.

When the burn area bed was clean with good granulation tissue, split-thickness skin graft (STSG) was used to cover the burn area and the raw fasciotomy area. Complications were detected as they occurred and were managed accordingly. The patients were followed up until the day of discharge.

Results

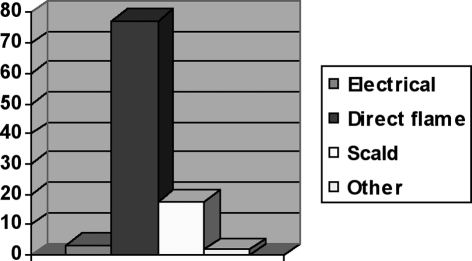

Over a period of four years (Jan. 2004-Dec. 2007), 362 patients were admitted to the specialized burns unit of the Royal Rehabilitation Centre at King Hussein Medical Centre. Twelve patients (3.3%) had suffered electrical burns, 64 (17.7%) had scald burns, 280 (77.3%) had direct flame burns, and six (1.7%) had burns due to other causes, including chemicals ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1. Causes of burns treated in the burns unit.

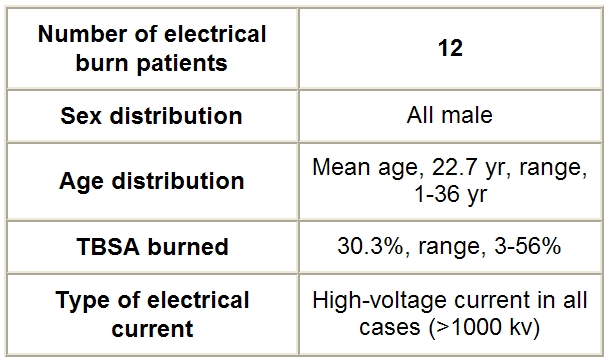

The electrically burned patients admitted to the burns unit all had high-voltage current burns (>1000 kV). All were male. The mean age was 22.7 yr (range, 11-36 yr) and mean total body surface area (TBSA) burned percentage was 30.3% (range, 3-56%) ( Table I ).

Table I. Demographic data.

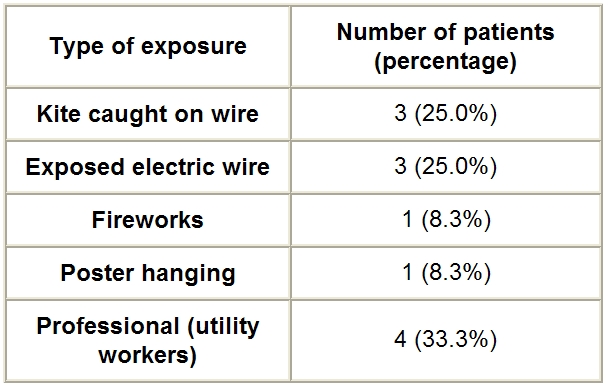

The causes of the electrical burn were as follows: a kite caught in high-voltage wires (3 patients = 25%), an exposed live electric wire (3 patients = 25%), handling fireworks (1 patient = 8.3%), and hanging a poster (1 patient = 8.3%); four patients (33.3%) were utility workers ( Table II ).

Table II. Causes of the electrical burns considered.

The body areas involved were as follows

four patients (33.3%) had burns involving the face

all patients had hand involvement: five (41.7%) with both hands and upper limb involvement; seven (58.3%) with a single upper limb burn - of these, six (85.7%) had burns involving the right limb and one (14.3%) the left limb (all were right-handed)

six patients (50.0%) had involvement of the lower limbs: three (50.0%) in a single limb and three (50.0%) in both lower limbs

three patients (25%) had involvement of the chest and two (16.7%) had involvement of the anterior trunk ( Table III )

Table III. Site of burn.

Ten patients (83.3%) needed fasciotomy and nine (75.0%) needed STSG. Five patients (41.7%) needed limb amputation, one of whom of all four limbs. Two cases were below-knee amputations, one was a left-hand amputation and one a right above-elbow amputation. One patient (8.3%) had upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Three patients (25%) died: the main cause of death was septicaemia (two patients) and acute renal shutdown (one patient). The death rate increased with higher TBSA percentage burned (48%, 55%, and 56%) ( Table IV ).

Table IV. Complications of electrical burns.

The average hospital stay was 24.4 days (range, 2-60 days).

Discussion

Electrical injury is an important and a challenging problem in a burns unit. It can cause high mortality and morbidity. 2Although it is reported as being responsible for only a small percentage of admissions to burn units, i.e. from 2.7 to 9.0%1-4 (in our centre the percentage was 3.3%), electrical burn has very important functional and cosmetic disabling sequelae. The complex aspects of management are the complications resulting from the systemic effects of the electrical injury. The damage results from the local heating effect, which causes deep tissue damage by progressive devitalization secondary to thrombosis of the veins and arteries that are most affected by the current. 3, 4, 7, 9This leads to loss of organs. The higher the water content in the tissue the better the conduction and therefore the worse the damage. 4Local oedema around the necrotic damaged tissue causes progressive compression and obliteration of the microcirculation that leads to increased cutaneous tension and compartment syndrome. 4, 8, 9This is treated with fasciotomy.

In our study, most of the injuries were related to human error or to lack of knowledge and education. The fact that utility poles and wiring are often placed low down and close to buildings was also a factor. The injuries were therefore avoidable, as was also shown in other studies. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9All our patients were male - we attribute this finding to the greater exposure to high-voltage current in the male sex. The patients were all either of working age or children who were accidentally exposed (range, 11-36 years). The children’s accidents were due either to kites getting caught in electric wires or to playing with exposed live electric wires. In adults the accidents were work-related. Fireworks were the cause in one case. It is possible to attribute the accidents to the fact that most of the patients were not trained properly in the handling of electricity.

The burn pattern in all cases involved the upper limb and hands: 6, 7, 911 patients (91.7%) had right-hand involvement, while five (41.7%) had both hands involved. All our patients were right-handed. The lower limbs were involved in 50.0% of cases; both limbs were involved in half of these patients. The face was involved in four patients (33.3%), while the chest and anterior trunk were involved in five patients (41.7%). The percentage of the burned area was variable, ranging from 3 to 56% (average, 30.3%).

After admission, all the patients needed early debridement and daily skin care by dressing with topical agents, e.g. silver sulphadiazine, which was found to reduce the bacterial charge. 4Ten patients (83.3%) needed immediate fasciotomy to prevent compartment syndrome. The fasciotomies were performed along the axis of the limbs. All patients needed STSG to cover the defect. 3, 5, 9Five patients (41.7%) in the end needed limb amputation owing to severe tissue damage and necrosis. 6, 7, 8Two of these five (40%) had below-knee amputation, one (20%) had right above-elbow amputation, one (20%) had left-hand amputation, and one patient (20%) had all four limbs amputated. One of the twelve patients (8.3%) had upper gastrointestinal bleeding, despite being on H2 blockers; this patient, who was being monitored because of a drop in cardiovascular pressure, was shifted to intravenous proton pump inhibitors and the problem resolved spontaneously. We had three deaths (25%), a rate comparable to that found in other studies. 1, 2, 7One patient died on the second day of admission owing to severe acute renal failure secondary to massive myoglobinuria - this patient had a TBSA burned percentage of 55%. The other two deaths were related to sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. 1, 2, 3Of these two, one died after five days (TBSA burned, 56%) and the other after two weeks (TBSA burned, 48%). Mortality was related to higher burn surface area. Wide-spectrum antibiotics were used empirically to treat the sepsis initially, and these were changed later on the basis of the tissue cultures.

The average duration of hospital stay was 24.4 days (range, 2-60 days). The greater the burn areas the longer the hospital stay. 7The longest stay was for a patient with a TBSA percentage of 45% who had four limb amputations.

This study reflects the severity of electrical burn and its serious consequences and shows the importance of prevention through education.

Conclusion

Electrical injury is a very serious and important type of burn, which constitutes a considerable health hazard. It provides a great challenge in management both in the acute stage and throughout the rehabilitation period. Victims can end up with major disabilities. Most of the injuries are preventable with proper education and knowledge.

References

- 1.Subrahmanyam M. Electrical burn injuries. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 2004;17:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Gallal A.R.S., Yousef S.M. Electrical burns in Benghazi urban area. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 1998;9:198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babík J., Sandor, Sopko Electrical burn injuries. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 1998;11:153–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faggiano G., De Donno G., Verrienti P., Savoia A. High-tension electrical burns. Ann. Burns Fire Disasters. 1998;11:162–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammadi A.A.., Amini M., Mahrabani D., Kiani Z., Seddigh A. A survey of 30 months’ electrical burns in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences Burn Hospital. Burns. 2006;34:111–3. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberal M., Kaynaroglu V., Öner Z., Gülay K., Bayraktar U., Bilgin N. Epidemiology of electrical burns in our centre. Ann. Medit. Burns Club. 1989;2:14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke J.F., Quinby W.C., Bondoc C., et al. Patterns of high-tension electrical injury in children and adolescents and their management. Am. J. Surg. 1977;133:492. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberal M. Electrical burns: A five-year experience - 1985 Evans Lecture. J. Trauma, 1986;26:103. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haberal M., Öner Z., Gülay K, Bayraktar U., Bilgin N. Severe electrical injury and rehabilitation. Ann. Medit. Burns Club. 1988;1:121–3. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(89)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]