Summary

This study covered 40 patients (22 females and 18 males) suffering from post-burn hand deformities admitted to Assiut University Hospital and Luxor International Hospital (Egypt) from June 2004 to May 2006. Their ages ranged between 4 and 45 yr (mean, 24.5 yr). They presented a variety of post-burn hand deformities, e.g. dorsal hand contracture (14 cases), volar contracture (10 cases), first web space contracture (3 cases), post-burn syndactyly (2 cases), wrist deformity (3 cases), skin and tendon affection (2 cases), and complex deformity (6 cases). All the patients underwent a variety of surgical procedures specific to the individual post-burn hand deformity. Post-operative splinting of the hand for 10 days was performed in patients with skin graft to prevent recontracture. The post-operative physiotherapy programme started in the second week in order to achieve good functional results. The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 20 months. The results were satisfactory in most of the cases as regards the quality of coverage, which was achieved in the majority of cases. In one case there was partial loss of the skin graft, which healed by secondary intention; full range of motion was achieved in most patients, but not those with joint affections. On the basis of our results, we can conclude that the management of post-burn hand deformities depends on several factors. Initial treatment of the burned hand is of great importance for the prevention of secondary deformities. In secondary burn management the first step is the release of the contracture, which should be complete and include all contracted structures. The second step is the proper selection of methods of coverage for resultant defects, using either skin grafts or flaps depending on the presence of exposed tendons, nerves, or joints. The third step in order to obtain a very good function is the activation of an intensive physiotherapy programme immediately after the operation.

Keywords: DIFFERENT, SURGICAL, RECONSTRUCTION, POST-BURN, MUTILATED, HAND, PROSPECTIVE, COHORT, PATIENTS

Abstract

Cette étude prend en considération 40 patients (22 femelles et 18 mâles) atteints de difformités de la main post-brûlure hospitalisés dans l'Hôpital de l'Université d'Assiout et l'Hôpital International de Louxor (Egypte) entre juin 2004 et mai 2006. L'âge des patients variait entre 4 et 45 ans (moyenne, 24,5 ans). Ils présentaient diverses difformités post-brûlure, par exemple contracture dorsale de la main (14 cas), contracture palmaire (10 cas), contracture du premier espace interdigital (3 cas), syndactylie post-brûlure (2 cas), difformité du poignet (3 cas), affection de la peau et des tendons (2 cas) et difformité complexe (6 cas). Tous les patients ont subi diverses procédures chirurgicales spécifiques selon leur difformité post-brûlure individuelle. L'application post-opératoire des attelles à la main pour 10 jours a été effectuée dans les patients traités avec greffe cutanée dans le but de prévenir la répétition de la contracture. Le programme de physiothérapie post-opératoire a commencé dans la deuxième semaine pour réaliser de bons résultats fonctionnels. La période successive de contrôle variait entre 6 et 20 mois. Dans la plupart des cas les résultats étaient satisfaisants pour ce qui concerne la qualité de la couverture, réalisée avec succès dans la majorité des cas. Un patient a subi une perte partielle de la greffe cutanée, à laquelle on a remédié par intention secondaire; une amplitude complète de mouvement a été réalisée dans la plupart des patients, avec l'exception des patients atteints d'affections des articulations. Sur la base de ces résultats les Auteurs concluent que la gestion des difformités post-brûlure de la main dépend de beaucoup de facteurs. Le traitement initial de la main brûlée est très important pour prévenir la manifestation de difformités secondaires. Dans la gestion des difformités secondaires des brûlures le premier pas est la libération de la contracture, qui doit être complète et inclure toutes les structures contractées. Le deuxième pas est la sélection exacte des méthodes de couverture des défauts résultants, avec l'emploi ou de greffes cutanées ou des lambeaux selon la présence de tendons, nerfs, ou articulations exposés. Le troisième pas pour obtenir une fonction optimale est l'activation d'un programme intensif de physiothérapie immédiatement après l'opération.

Introduction

The hand is the main interface between man and his environment. It is an organ of perception and expression. 1Unfortunately, it is also the most vulnerable part of the body to be affected by burn injuries. These injuries are unique and therefore categorized as major injuries by the American Burn Association, a categorization that emphasizes the importance of the hand not only to the burned individual but also to society as a whole.

Post-burn hand deformities, unlike other post-burn deformities, have a wide variety of presentations. It is important to note that the deeper structures (other than the skin) can contribute to the contracture. The combinations of deformities can have bizarre presentations, especially when there is a flexion contracture of one joint and an extension contracture of the adjacent joint.

Management of post-burn hand deformities can be a lengthy and complicated procedure. The reconstructive surgeon tackling the problem must consider the patient’s social and occupational needs as well as other factors such as other post-burn deformities in the body and the patient’s psychological and motivational status.

Patients and methods

This study dealt with 40 patients suffering from post-burn hand deformities admitted to Assiut University Hospital and Luxor International Hospital (Egypt) from June 2004 to May 2006. The age range was between 4 and 45 yr, with a mean age of 24.5 yr. Twenty-two patients were females and eighteen males. They presented a variety of post-burn hand deformities, e.g. skin contractures in the form of dorsal contractures, volar contractures, web syndactyly, first web contractures, and wrist contractures; skin and tendon deformities; and complex deformities (skin, tendon, and joint deformities). The deformities were either within the normal range of motion or outside it.

Patient evaluation

Patient evaluation included the accident’s complete history, its nature, primary burn management, and its duration:

Evaluation of hand functions: the patient was asked to specify the impairment caused by the deformity.

Local examination of the hand, including: a. General appearance of the hand and its position at rest. b. Direct observation of hand activities, using Jebsen’s test. c. Skin examination. d. Joint movement. e. Tendon examination. f. Vascular examination. g. Clinical nerve examination.

Investigations

The investigations were performed in relation to the severity of the patients’ condition and to the surgical procedures performed (plain X-ray, MRI, Doppler ultrasound).

Surgical procedures

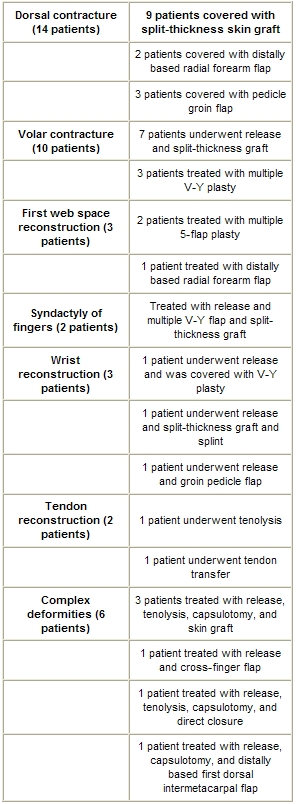

All patients underwent a variety of surgical procedures specific to the management of individual post-burn hand deformity ( Table I ). When the deformity presented bilaterally, the more affected hand was operated on first, regardless of hand dominance.

Table I. The various surgical modalities.

Anaesthesia was in several forms: local intravenous in 16 patients, brachial plexus block in 8 patients, and general anaesthesia in 16 patients. A tourniquet was used in all cases.

Post-operative care: all patients received the following:

Broad-spectrum antibiotic depending on body weight for 7 days post-operatively.

A strong anti-inflammatory for 5 days post-operatively.

Elevation of the hand to prevent post-operative oedema and alleviate pain.

A light bandage and the monitoring of hand vascularity in the first 48 h, based on an examination of colour, temperature, and capillary refilling of the fingers and hand as a whole.

A post-operative hand splint was constructed in routine manner, especially in cases requiring skin graft, in order to prevent recontracture and also post-operative oedema in ideal positions (30º wrist extension, 90º M.P., joint flexion, extension of PIP joint, IP, and DIP joints) for 8-10 days.

A physiotherapy programme was planned for each case, depending on the doctor’s surgical procedure, expressed as:

passive and active exercises of the fingers, starting from the second week post-operatively, to obtain a good range of motion

ultrasound waves applied for several sittings to relax the burn scar

pressure garments and anti-scar cream were applied from the third week post-op for 6 months in order to prevent the development of hypertrophic scars

in cases involving tendon repair, the splints were left for 6 weeks, with controlled exercises on the affected finger in order to prevent development of tendon adhesion. The patient then followed an extensive physiotherapy programme.

Follow-up

The follow-up period ranged between 6 and 20 months.

Results

With regard to sex, an analysis of the patients shows a predominance of females over males, while with regard to age the majority of the patients were under 30 years of age. There was a predominance of fire as the initial injury. The majority of deformities consisted of skin contractures (dorsal contractures, volar contractures, syndactyly, and first web and thumb deformities), with a predominance of dorsal contractures (46.33%). With regard to contractures there was a predominance of little finger contractures (70%).

Both hands were affected in 8 cases, the right hand alone in 15, and the left alone in 17.

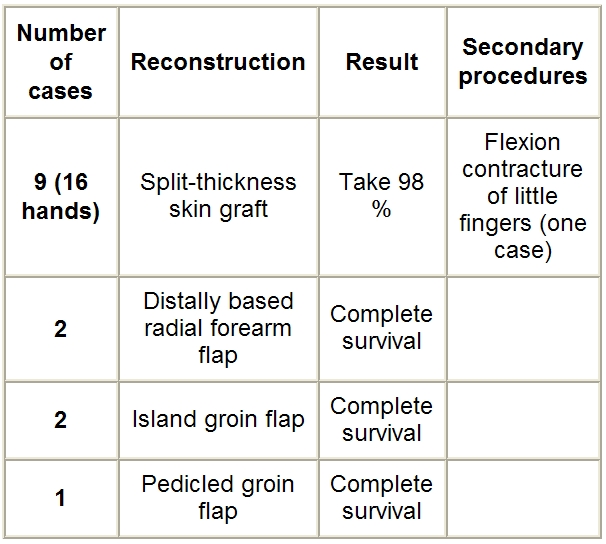

Dorsal contracture, present in 14 cases, was treated with release and covered by split-thickness skin graft, distally based radial forearm flap, and groin flap ( Table II ).

Table II. Results of reconstruction in dorsal contractures.

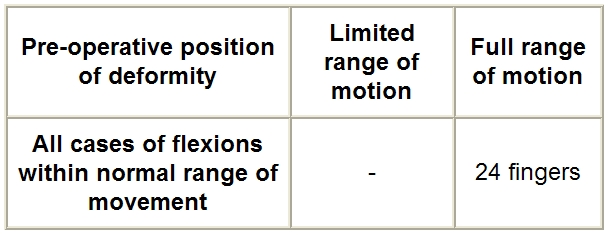

Functional gain after dorsal contracture reconstruction is reported in Table III .

Table III. Functional gain after dorsal contracture reconstruction.

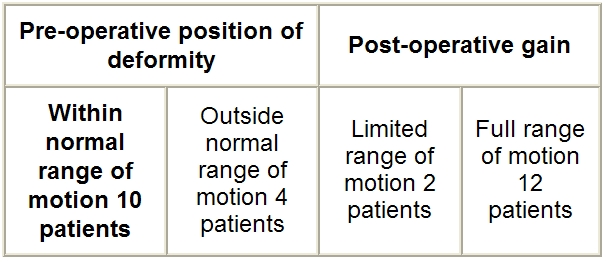

A volar contracture was present in 10 cases, requiring after release of the fingers either split-thickness graft and splint or multiple V-Y plasty ( Table IV ).

Table IV. Results of reconstruction of volar contractures.

Functional gain after volar contracture reconstruction is reported in Table V .

Table V. Functional gain after volar contracture reconstruction.

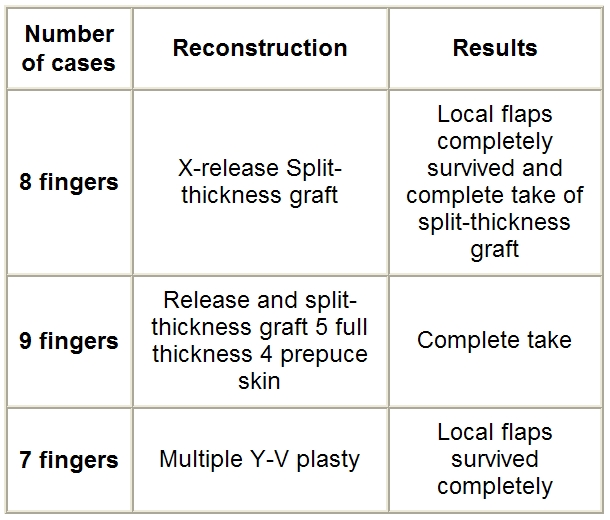

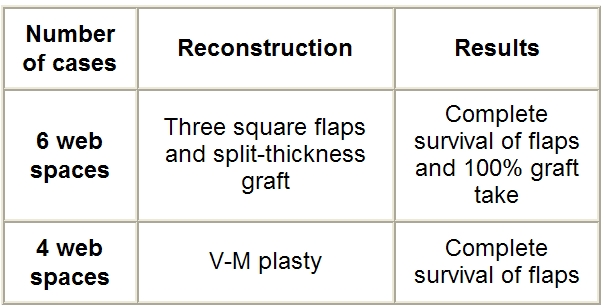

There were two cases of burn syndactyly treated with release and multiple V-Y plasty with very good results ( Table VI ).

Table VI. Results of reconstruction of syndactyly.

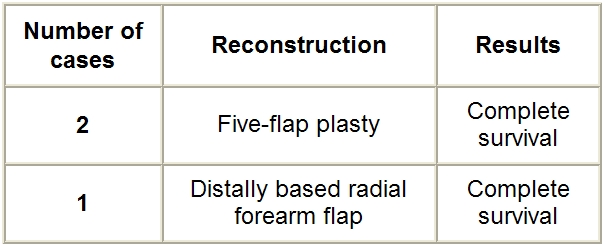

Three cases presented varying degrees of first web contracture, which was treated either with the multiple 5-flap technique or a distally based radial forearm flap ( Table VII ).

Table VII. Results of reconstruction of first web contractures.

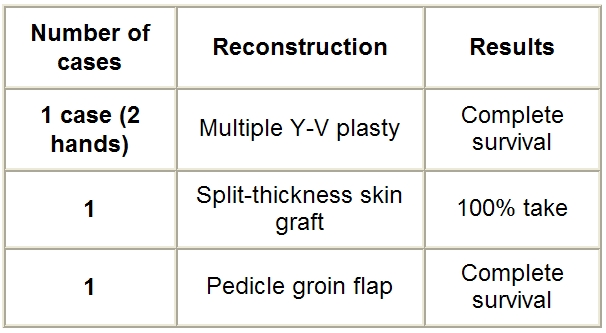

There were three cases of patients with wrist contracture released either by split-thickness skin graft or by multiple Y-V plasty or pedicle groin flap ( Table VIII ).

Table VIII. Results of reconstruction of wrist deformities.

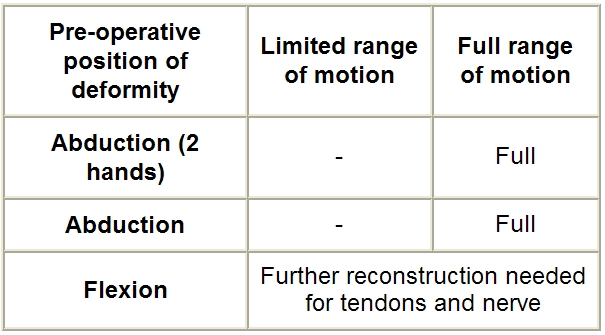

Functional gain after wrist reconstruction is reported in Table IX .

Table IX. Functional gain after wrist reconstruction.

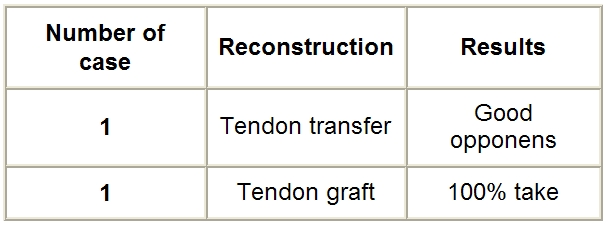

Two patients presented a tendon deformity treated either by tenolysis or by tendon graft ( Table X ).

Table X. Results of reconstruction of tendon deformities.

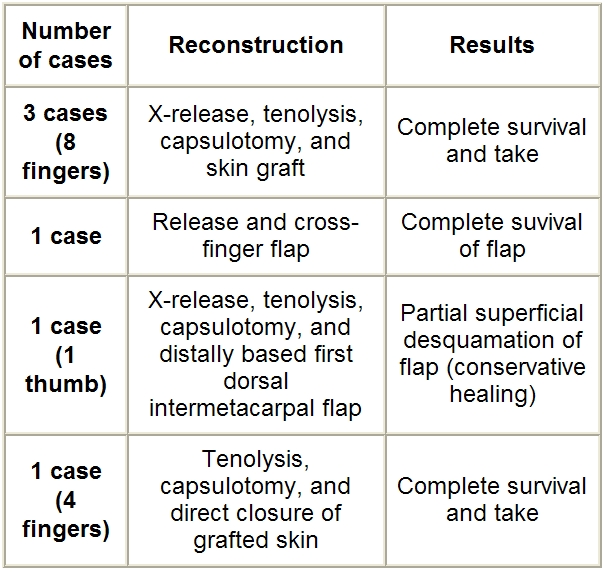

Six patients had varying degrees of complex deformities that required a different attack on both the joint and tendon in addition to the skin problem ( Table XI )

Table XI. Results of reconstruction for complex deformities.

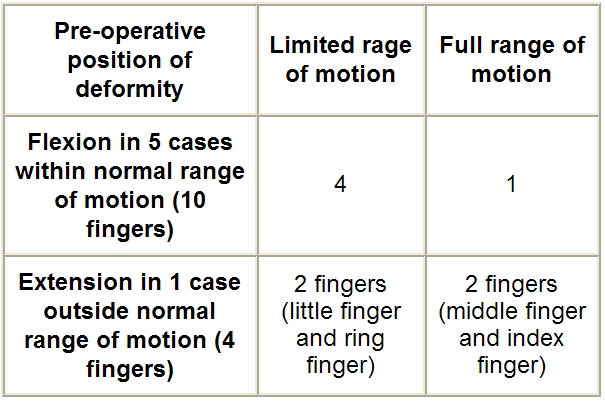

Functional gain after reconstruction of complex deformations is reported in Table XII

Table XII. Functional gain after reconstruction of complex deformities.

List of cases

Case 1 - Post-burn dorsal contracture treated with release and split-thickness skin graft

Case 1a - Pre-operative dorsal contracture

Case 1b - Intra-operative release of contracture

Case 1c - Split-thickness skin graft over dorsum of hand

Case 1d - Post-operative extension with complete graft take

Case 1e - Good post-operative flexion with split-thickness graft

Case 2 - Dorsal contracture treated with distally based radial forearm flap

Case 2a - Pre-operative severe dorsal contracture

Case 2b - Intra-operative plan of radial forearm flap

Case 2c - Post-operative good coverage with radial forearm flap

Case 3 - Volar contracture treated with multiple V-Y plasty

Case 3a - Pre-operative post-burn volar contracture over fingers

Case 3b - Intra-operative plan of multiple V-Y plasty releasing finger contracture

Case 3c - Post-operative view after release of contracture and coverage with multiple V-Y plasty and split-thickness skin graft

Case 4 - First web space release using radial forearm flap

Case 5 - Syndactyly treated with multiple V-Y plasty

Case 5a - Post-burn finger syndactyly

Case 5b - Intra-operative view

Case 5c - Post-operative view after release and multiple V-Y plasty

Case 6 - Post-burn contracture of wrist

Case 6a - Pre-operative wrist contracture

Case 6b - Intra-operative release of burn scar

Case 6c - Post-operative good coverage and restoration of function by split-thickness skin graft

Case 7 - Complex deformity in distal phalanges of thumb

Case 7a - Pre-operative deformed thumb

Case 7b - Intra-operative view

Case 7c - Late post-operative condition with good coverage and restoration of function

Fig. 1a. Case 1, pre-op.

Fig. 1b. Case 1, intra-op.

Fig. 1c. Case 1, late post-op.

Fig. 2a. Case 2, pre-op.

Fig. 2b. Case 2, intra-op.

Fig. 2c. Case 2, post-op.

Fig. 3a. Case 3, pre-op.

Fig. 3b. Case 3, intra-op.

Fig. 3c. Case 3, early post-op.

Fig. 5a. Case 5, pre-op 2.

Fig. 5b. Case 5, intra-op.

Fig. 5c. Case 5, post-op 2.

Fig. 6a. Case 6, pre-op.

Fig. 6b. Case 6, intra-op.

Fig. 6c. Case 6, post-op.

Fig. 7a. Case 7, pre-op 1.

Fig. 7b. Case 7, intra-op 2.

Fig. 7c. Case 7, post-op 1.

Discussion

The complexity of post-burn deformity lies in the fact that several structures may contribute to the deformity itself, the skin contracture, joint stiffness, and tendon adhesions. Thus the pre-operative evaluation of the post-burn deformed hand is very important. Unfortunately, this is a difficult task and frequently the surgeon is forced to resort to special investigations or to wait for the intra-operative assessment in order to define the problem.

In this study of dorsal contracture treated with a split-thickness skin graft in nine patients, a thick split-thickness skin graft was used as coverage, yielding excellent results in the patients: no graft was lost totally and partial loss, secondary to infection, was recorded in only one case. Our results are consistent with previous reports 6in which contractures of the dorsum of the hand were managed using skin graft as coverage rather than the better split-thickness or full-thickness skin grafts. We agree 7that the thick split-thickness skin graft was proposed as a practical compromise.

In our study the hand was immobilized in the fist position for 8-10 days after skin grafting - the greatest amount of skin can be grafted in the fist position, avoiding secondary contractures due to graft contraction, and no joint stiffness was recorded in this period. This manoeuvre is consistent with that of Burm et al., 8who analysed the length of the dorsal hand surface in the hand positions and found that the total length in the fist position was significantly increased compared with the anatomical and safe positions. Prolonged periods of post-operative physiotherapy, splinting, and pressure garments were required to maximize the aesthetic and functional outcome.

In one case a radial forearm flap was used as coverage, achieving a satisfactory result. The radial forearm flap has many advantages, resulting in its excellent reputation. As already said, it is a reliable flap with a robust arterial inflow through a retrograde flow into the radial artery, and good venous drainage through the venae comitantes of the radial artery. It yields skin that is thin, pliable, and hairless, plus a large skin territory to be included in the flap.

Our results were consistent with others in the literature.

In three cases groin flaps were used for soft tissue coverage. The groin flap has long been the preferred option in the coverage of hand defects. Very long flaps can be designed, far beyond the territory supplied by the well-identified artery. No complications have been observed with these flaps, and good results have been achieved.

This flap’s drawbacks are that it is thick and needs prolonged immobilization until separation. Our results were consistent with those of Koshima et al., 12who performed a groin flap in the coverage of 65 patients with post-burn deformed dorsum of the hand.

In our study we observed that good functional results were obtained when the positions of the deformities of the metacarpophalangeal joints were within the normal range of motion, while there was less functional gain when the positions of deformity of these joints were outside the normal range.

With regard to the release of volar contracture, several options for the coverage of these palmar finger defects have proved to be reliable. X-release is performed across the line of contracture and the edges are sutured, bringing soft tissues from the lateral sides and skin graft to maximize the benefit of using local tissue release. 13Y-V advancement, or V-advancement with Z-plasty as a combination, improves the release of linear flexion contractures in the fingers, including the thumbs.

The results of this investigation were consistent with previous reports 15, 16on the management of palmar contractures using skin graft and local flaps as coverage. We also agree 17that there is no significant difference between split-thickness and full-thickness skin grafts, although it is claimed that split-thickness skin grafts have fewer tendencies towards hyperpigmentation, resulting in superior cosmesis. Also in our method the management of palmar contractures provided functional gain rather than cosmetic results, because the positions of deformity were usually within the normal range of motion. However, in cases of partial amputation of the fingers, the use of finger prostheses to replace missing phalanges or fingers improves the appearance of a burned hand.

Surgery in post-burn syndactyly seeks to accomplish one of three goals: to break the line and add length to a straight-line contracture; to re-create the web space commissure by using a local flap; and to add skin from outside the local area for severely scarred web spaces. Multiple local flaps were used for correction of syndactyly, depending on the availability of unscarred skin. 18Z-plasty, V-M plasty, square flap, five-flap release, and a dorsal flap with lateral digital extensions are very helpful methods for the management of post-burn syndactyly. 19, 20, 21With our method all cases of post-burn syndactyly were managed using the multiple square flap. The results were excellent and proved the reliability and feasibility of using local flaps in web contractures with long-term success. This is consistent with the work of Lapid and Sagi, 22who used a multiple square flap for the management of 33 cases of post-burn syndactyly.

First web adduction contractures (3 cases)

Local flaps are the best option, if available; they are thin, of similar colour, and matching in texture, and they do not mutilate other body regions.

As reported in the present study, two patients were treated with skin release, with partial release of the adductor pollicis and first dorsal interossei and reconstructed using five-flap Z-plasty. Satisfactory results were achieved in these patients.

In the other patient, skin release was performed, with partial release of the adductor pollicis. The resultant defect was covered by a distally based radial forearm flap with ample good coverage, which is consistent with the findings of Safak and Tecik.

Wrist deformities (3 cases)

The first case had a bilateral abduction deformity managed by multiple Y-V plasty extending from the dorsum of the thumb to the elbow. The other hand was corrected four months later by the same technique. The second case (dorsal and abduction contractures of the wrist and thumb) was managed with complete excision of the scar tissues, the resultant defect being covered with a skin graft. The hand and wrist were splinted for 10 days, until complete graft take, followed by early physiotherapy. In the third case (flexion contractures of the wrist), the contractures were released and the defects were covered by groin flaps, for further reconstruction of the flexor tendons and median nerve in the wrist. Satisfactory results were achieved in all cases.

Skin and tendon deformities (2 cases)

The first of these two cases consisted of loss of the extensor of the left thumb, which was managed by tendon transfer from the flexor digitorum superficialis of the ring finger for opponoplasty. The second case (post-burn loss of the medial three extensor tendons on the dorsum of the left hand) was managed with tendon grafts.

In both cases post-operative splintage of the hand was maintained in a position of ease for 6 weeks, allowing only controlled motion of the fingers in order to prevent tendon adhesion; this was followed by an extensive physiotherapy programme. Excellent results were achieved in all cases of tendon reconstruction considered in the present work.

Our plan in the primary covering of burn wounds was to provide a flap cover for further reconstruction of the underlying tendon pathology, while the second stage was for the actual tendon reconstruction.

We disagree with Yajïna et al. 27and El-Khatib, 28who for fear of infection performed coverage and tendon transfer as a composite flap in the same sitting.

Complex deformities (6 cases)

All six cases (skin, tendon, and joint deformities) were managed by release of the skin contractures, tenolysis, and capsulotomy with partial release of the collateral ligaments. Satisfactory results were achieved in all cases.

In the vast majority of patients, the initial thermal injury is limited to the skin: the underlying tendons and joints are usually spared. Prolonged wound healing, with its attendant oedema, infection, fibrosis, and immobilization, can lead to secondary joint contractures, the rupture of extensor tendon mechanisms, and the adhesion of gliding tissues.

In complex deformities where deep structures such as tendons, ligaments, and joints have been affected directly or as a result of improper initial therapy, the reacquisition of a full range of motion after reconstruction is not always possible. There may also be joint subluxation or deviations resulting from imbalance in the ligaments and muscular forces. Our results in the management of complex deformities were consistent with those of Graham et al.

Conclusion

On the basis of the results of the present investigation, we propose the following plan for the management of post-burn hand deformities:

The correct initial treatment of hand burns is a matter of great importance for the avoidance of secondary deformities as it guarantees hand function more surely than reconstruction.

The first step is the release of the contracture, which should be complete and include all contracted structures.

The second step is the proper selection of methods of coverage for resultant defects using either skin grafts or flaps depending on the presence of exposed tendons, nerves, or joints.

Step 3 is an intensive physiotherapy programme immediately after the operation in order to gain optimal function.

In dorsal contractures, the entire scar should be removed and any residual contracture should be released. Usually replacement or resurfacing with skin grafts is satisfactory. Flap coverage may occasionally be necessary if further reconstruction for deep structures such as tendons or joints is planned. Tissue transfer, even with free tissue, is not sufficient to improve hand function as long as tendon and joint problems still exist.

Good functional results are achieved when the positions of hand joint deformity are within the normal range of motion, while there is less functional gain when the positions of hand joint deformity are outside the normal range of motion. Popularization of arthroplasty, using joint prosthesis in some selected cases, may thus improve functional gain.

References

- 1.Robson M.C., Smith D.J., VanderZee A.J., et al. Making the burned hand functional. Clinics in Plast. Surg. 1992;19:663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson D.L. The importance of the physical examination. Hand Clin. 1997;13:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gökalan L., Özgür F., Gürsu G., Keçik A. Factors affecting results in thermal hand burns. Annals of Burns and Fire Disasters. 1996;9:222–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo S.H., Seul J.H. Optimizing the correction of severe post-burn hand deformities by using aggressive contracture release and fasciocutaneous free tissue transfers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107:1. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burm S.J., Oh J.S. Fist position for skin grafting on the dorsal hand - clinical use in deep burns and burn scar contractures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2000;105:531. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwuagwu F.C., Wilson D., Bailie F. The use of skin grafts in post-burn contracture release - a 10-year review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;103:1198. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199904040-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann R., Gibran N.S., Engray L.H., et al. Prospective trial of the thick vs standard split-thickness skin grafts in burns of the hand. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22:390. doi: 10.1097/00004630-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burm S.J., Chung H.C., Oh J.S. Fist position for skin grafting on the dorsal hand. I. Analysis of length of the dorsal hand surface in hand positions. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;104:1350. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199910000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Qattan M.M., Ziesmann M. Immediate desyndactylization of the reverse radial forearm flap. J. Hand Surg. 2000;25:61. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.1999.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogachefsky R.A., Mendietta C.G., Galpin P., et al. Reverse radial forearm fascial flap for soft tissue coverage of hand and forearm wounds. J. Hand Surg. 2000;25:358. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adani R., Tarallo L., Macococcio I. Island radial artery fasciotendinous flap for dorsal hand reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2001;47:83. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koshima I., Nanba Y., Tsutsui T., et al. Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap for reconstruction of limb defects. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004;113:233. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000095948.03605.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Oteify M.A. A versatile method for the release of burn scar contractures. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1981;34:326–8. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(81)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peker F., Celebiler O. Y-V advancement with Z-plasty - an effective combined model for the release of post-burn flexion contractures of the fingers. Burns. 2003;29:479. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(03)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson S.B., Miller J.G. Optimizing skin graft take in children’s hand burns - the use of Silastic foam dressings. Burns. 1993;19:519. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(93)90012-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barret J.P., Desai M.H., Herndon D.N. The isolated burned palm in children - epidemiology and long-term sequelae. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2000;105:949. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pensler J.M., Steward R., Lewis S.R., et al. Reconstruction of the burned palm - full-thickness versus split-thickness skin graft, long-term follow-up. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1988;81:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang L.Y., Yang J.K., Wei F.C. Reverse dorsometacarpal flap in digits and webspace reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1994:33–281. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pribaz J.J., Pelham F.R. Use of previously burned skin in local fasciocutaneous flaps for upper extremity reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1994;33:272. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyakusoku H., Fumiri M. The square flap method. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1987;40:40–6. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(87)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima T., Hayashi H., Terao Y. A dorsal flap with lateral digital extensions for palmar web contractures. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1995;48:236. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapid O., Sagi A. Three-square-flip-flap reconstruction for post-burn syndactyly. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2005;58:826. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharya S., Bhatnagar S.K., Pandey S.D., et al. Management of burn contractures of the first web space of the hand. Burns. 1992;18:54. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(92)90122-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraulin F.O.G., Thomson H.G. First web space deepening - comparing the four-flap and five-flap Z-plasty. Which gives the most gain? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1999;104:120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaki M.S., Rifky M., Makeen K., et al. Reversed radial forearm flap for reconstruction for the first web of the hand. Egypt. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1994;18:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safak T., Kecik A. Coverage of a thumb wound and correction of a first web space contracture using a longitudinally split reverse radial forearm flap. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2001;4:453. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200110000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yajima H., Inada Y., Shono M., et al. Radial forearm flap with vascularized tendons for hand reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1996;98:328. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199608000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Khatib H. Tendofascial island flap based on distal perforators of the radial artery - anatomical and clinical approach. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004;113:545. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000101820.53946.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham T.J., Stern P.J., True M.S. Classification and treatment of post-burn metacarpophalangeal joint extension contractures in children. J. Hand Surg. 1990;15:450. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(90)90058-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]